Boulez on Carter

-

Upload

dylan-richards -

Category

Documents

-

view

249 -

download

1

Transcript of Boulez on Carter

-

8/12/2019 Boulez on Carter

1/6

Pierre Boulez in Interview (2): On Elliott Carter, 'A Composer Who Spurs Me on'Author(s): Philippe Albra and Pierre BoulezSource: Tempo, New Series, No. 217 (Jul., 2001), pp. 2-6Published by: Cambridge University PressStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/946866.

Accessed: 09/03/2014 20:45

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at.http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

.

Cambridge University Pressis collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Tempo.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 134.10.132.57 on Sun, 9 Mar 2014 20:45:26 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=cuphttp://www.jstor.org/stable/946866?origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/stable/946866?origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=cup -

8/12/2019 Boulez on Carter

2/6

PhilippeAlberaPierre Boulez in Interview (2):on Elliott Carter,'a composer who spursme on'(InTempo 216 PierreBoulez,interviewedy SimonMawhinney,alkedabouthis own recentmusic. Thepresentnterview,onductedn French,n Paris nJune2000 waspublishedunderthe title '...un Compositeurqui m'oblige avancer...';t appearsere n Englishforthefirst ime,translatedySueRose.)PHILLIPE ALBERA: Whendid you irst get to knowCarter'smusic?PIERRE BOULEZ: It was at a Domaine Musicalconcert in the early 1950s. I didn't know Carterat that time: the ParreninQuartet suggestedweincludehis FirstStringQuartet n the programme.I then met him briefly at the SIMC FestivalinBaden-Baden where Le Marteau ansMaitrewasgiven its firstperformance. His Cello Sonata, awork still clearly influenced by the neoclassicalstyle, was performed there. Much later, aroundthe mid-1960s, I heard the Double Concerto forPiano and Harpsichordand I got to know himmuch better then.PA:Carter'sritingwas basedon completely ifferentprincipleso thoseofserialwriting, lthought was ustas innovative: owdidyou regardt at thetime?PB: I was very interested in it The First Quartethad intriguedme in the early 1950s because thestyle of writing was completely different fromours, particularly he rhythmicwriting, which isextremely complex. I remember being evenmore struck by his use of rhythm than by histreatmentof intervals.When I studied his scoresin depth and got to know him better, which wasin the 1960s - and we had alreadycome a longway from Darmstadt- I was very interested inexploring his concept of form, with those lay-ered structures hat resemble charactersn a play.I then asked him to explain severalof his worksto me, such as the Concerto for Orchestra,forexample, a work which I subsequently playedon numerous occasions, especially on tour. Ithen commissioned the Symphony of ThreeOrchestrasor the New York PhilharmonicOrchestra. Since then, I've always taken a keeninterest in his work and we have includedalmost all his pieces for smaller forces in theEnsemble InterContemporain's programme,including two works that we commissioned:

Penthode nd the Clarinet Concerto.PA: Yousay you were truck,rom thefirsttimeyouheard he FirstStringQuartet,by therhythmicspectof Carter'swriting...PB:Yes, I wasimmediately ascinated y hisrhyth-mic writing. I think the principle of rhythmicmodulation is particularlynteresting. The shiftsin rhythmicvaluesareperfectlyclear where theyoccur in the writing; the rhythmic relationshipsreach their fullest expression, as it were, whenthey can be heard. In some cases, however, youhave to rely on the metronomic relationships.You realize this when conducting, because ifyou're not in control of what you hear, therhythmic modulations are executed moreloosely. This idea is found in a simpler form inStravinsky'swork. More often than not, he usedrelationships of 3 to 2 or 4 to 3, as in theSymphoniesforWindInstruments,work which isentirely basedon rhythmic relationshipsof 2, 3,and 4.PA: Do you thinkthat Carter's otionofmetricmod-ulation temsdirectlyfromtravinsky?PB: Probably. From Stravinskyand Nancarrow.In actualfact, it was Carterwho introduced meto the latterat the time of the Double Concerto.His music made a great impression on me Butthe relationships n his work are alwaysprecisebecausethey are executed mechanically,althoughyou have to identify the units to detect them.PA: Yourconcept f note durationswas very diferentto Carter's n the 1950s. Did your discovery f theprinciples fmetricmodulationauseyou to alteryourapproach?PB: Yes, Carter's music gave me a great deal offood for thought, particularly after I beganconducting his works. My approachat that timewas, in fact, a point-based one, from which Iwas trying to distance myself since I was wellaware of its limitations;as a result, in my ThirdPiano Sonata,I introduced the idea of blocks oftime. This is because, in a strictly point-basedstyle of writing, there are, by force of circum-stances,statisticallymany more long values thanshortvalues, so that the pulse does not rely on aprimordialequalitybetween the differentvalues.This is also why, at the time, I decomposed the

This content downloaded from 134.10.132.57 on Sun, 9 Mar 2014 20:45:26 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/12/2019 Boulez on Carter

3/6

PierreBoulez in InterviewII):on ElliottCarter, acomposer hospursme on' 3chords: to ensurethatthe tempo was determinedby the act of decomposing the chords ratherthan by a single value. Another point of interestin Carter'smusic was the principleof the written-out accelerandi nd ritardandiwhich are oftenfound in his music and which are extremelyeffective. One might say that these are primarilygestures;but, in Carter'swork, they form partofthe structurealong with variousintricatelyover-laid values.PA: Youraised hequestion fharmony t a veryearlystagewithin heserialmovement, hichnitiallydidn'tpay muchattentiono it. How didyou regardCarter'ssystem n thisdomain,a systemwhichfurthermoreeformalizedquiteearly?PB: He explained his system of intervalsto mewhen we were working together. His principleentailed focusing on certain dominant intervalswhich resultedin a comparativesimplificationofthe harmonic structure. I found this interesting,but it didn't have a greatimpact on me becauseI have another way of working, even though Itoo base my writing on harmonic concepts. Tomy mind, a chord or an initial interval cangenerate many things, either when it proliferatesor when it becomes distorted. In my experience,the myriad possible combinations must alwaysalready exist within the cell, so to speak. I per-sonally work from proliferatingor symmetricalchords organized around an axis; in my view,what is important is the parallel reproduction,the symmetrical reproduction or the defectivereproduction in the actual structure of theharmonic writing. To these, you could also addunrecognizable reproduction, where the sameelements are placed in a completely differentorder, in inverted registers:you can just abouthear it's the same combination, but you cannotsaywhy. So there areseveralstages:total identi-fication, partial identification which changesprogressively and variation which alters theposition of the elements and where it is as muchas you can do to recognize the density.Detection, in these circumstances, comes tooearlyor too late: if one knows there will be fifthsand seconds, it is too early and if one says tooneself: 'Yes, that's right, there were fifths andseconds all over the place', realization hasoccurred after the event, too late. My conceptof harmonic structure s therefore very differentfrom Carter's dea.PA:Did you discuss ll thesecompositionalssuesandconcepts ithhim?PB: Yes, we discussed a great many things Butwhen I think back now, I would say that ulti-mately what appealed to me most about hiswork were his ideasabout form: the principleof

continuity, in which forms are superposed,cancel each other out, reappear,begin anew...This is an extremely complex idea, so complexin some casesthat it becomes difficult to follow,as for example in the Third StringQuartet.Thatwork reveals a speculative approachthat makesit possibleto view the form in a completely freshlight, eschewing the usual conventions orreceived wisdom. I didn't accept all Carter'sideas unquestioningly, of course, but they madea great impressionon me and this is particularlyevident in my more recent works.PA: Whatdoyou thinkof Carter's rchestralriting?PB: His orchestralwriting is well thought-outandperfectlyexecuted but I wouldn't sayit's themost innovative aspect of his work: I don'tthink his use of timbre is as inventive as his useof rhythmor form. By this, I mean that there areno unusualsounds, no sounds that strike the earbecause they've never been heard before. Theorchestra s certainlynot used in a conventionalmanner, but the instrumentsare used for theirtraditionalqualities:majesticbrass,eloquentwind,etc. Carter doesn't make use of trompe-l'oeil,perspective or the relationship between a realobject and a virtual object, which can be foundat a fairly simple level in the later work ofDebussy, or in Stravinsky'sFirebird, r again inworks by Strauss,who was a great illusionistwhen it came to orchestral writing. Carter'swriting is more akin, in this respect, to the typeof orchestralwriting produced by composers inthe Viennese School. Carter's work presents adirect transcriptionof the musical idea.PA:This is the distinctionRavel made between'instrumentation'nd 'orchestration'...PB: Absolutely. And Ravel was also a greatillusionist. In Carter's work, the discourse ismore importantthan the instrumentsused. Thisis also evident in his piano writing, which isunmoved by the idea of virtuosity, as Liszt sawit. However, I personallyam very fond of thisaspect: when composing for the piano, I'mnaturallydisposedtowardsvirtuosity,which cangenerate ounds hat haveneverbeen heardbefore.PA:In yourview, doesCarter'smusicfallwithin thetraditionof the Americanultra-modernismf the1920s, particularlyhe musicofRuggles?And, moregenerally,what is its position in Americanmusictoday?PB: With regard to the American music scene,you might say it is very isolated, particularlynow. This is actually why I'd compare him toRuggles, although obviously he has writtenmuch more than him. Ruggles also came upwith some non-tonal solutions, but he lacked asystematic approachwhich probably prevented

This content downloaded from 134.10.132.57 on Sun, 9 Mar 2014 20:45:26 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/12/2019 Boulez on Carter

4/6

4 PierreBoulez in InterviewII):on ElliottCarter,'acomposer hospursme on'

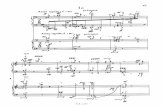

Elliott Carter nd PierreBoulez areseentogethern New York n 1977, during ehearsalsorCarter's A Symphony f ThreeOrchestras'him from writing a greatdeal, because you needa systematic approachif you are to develop yourideas. I think, on the other hand, that Carter'smusic is very different from that of Ives, whotackles trite ideas and eccentricsubjects n a fairlyloose form.

What I find interesting about Carter'swork,in comparison with someone like Messiaen,who belongs to the same generation, is that hetook a long time to find his own voice.Messiaen was himself right from the start: hisearly works, despite Franck's clear influence,used a modal language that was alreadyhis own:it is completely unmistakable. Then his workunderwent a fairlysudden change, at the time ofthe Etudes de Rythme and Chronochromie:eheaded off in a different direction. In his finalperiod, you get the feeling that he wanted tosalvage some of the earlierelements. Carter, onthe other hand, began almost anonymously. Iread through his ballet Pocahontas nce and if Ihad not alreadyknown it was by Carter,I wouldnever have guessed he was the composer: it ismore like Copland than Carter now So hehas gradually progressed towards a completelypersonal style of music, revealinga steadydevel-opment that has become increasingly markedwith the passingyears. Because he did a lot ofresearchat one time and because he spent a great

deal of time exploring ideas, he composed at arelatively slow pace. And then, suddenly, themusic started to flood out, as though someonehad opened the sluice gates.There arealsovarious historicalreasons or thisslow process of maturation. When I organizedamini-festival in New York to celebrate thecentenary of Ives's birth, I took a closer look atmusical life in the United Statesin the 1920s andI realised that those years were marked by agreat deal of avant-garde activity. Varese wasone of the key figures. There were someextremely interesting composers around,such asRuth Crawford Seeger, for example. However,after the economic crisis of 1929, there wasnothing, which was also reflected in the worldof art:at the time, people were urging artists oproduce large mural paintings, as in Mexico.This could be seen in dance with MarthaGraham and in music with the populist trend.And the fascinating hing is thatthiscorrespondedin every respect to Russian populism underStalin. The parallelbetween Americanpopulism,linked to the collapse of the capitalist system(which was to be reinstated)and socialistrealism,linked to the crisisin the Communist system inthe hands of a dictator, is actually very striking:it happened at exactly the same time. In alllikelihood, Carter's need to extricate himself

This content downloaded from 134.10.132.57 on Sun, 9 Mar 2014 20:45:26 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/12/2019 Boulez on Carter

5/6

PierreBoulez in InterviewII):on ElliottCarter, acomposer hospursme on' 5from such a background accounts for his slowdevelopment.PA:TheressomethingymbolicboutCarter'ssolation,particularlyn America,withregardo thepositionofthe moderncomposer:was this unavoidable, heinevitableesultof thehiatusbetween hedemandingcomposerndthepopularmusical onsciousness?PB: Yes, at the outset. But, in Carter'scase, theproblem may also be caused by the fact that heis not an 'appealing'composer:he doesn't try towin anyone over. This is why it is sometimeshard to convince those who have reservationsabout him. To my mind, this is due to hisnotion of sound. Some of his pieces, such asPenthode,or example, are ratheraustere,whichcan put people off. In terms of sound, one of hismost appealing works is A Mirroron WhichtoDwell. Personally, I like austeritybut I'm veryinterested in the phenomenon of sound and Ihave nothing againstcharm. The way in whichthe sounds are presented can create a feeling ofpleasure that improves our ability to make outthe form, for example.This createsa sense of bal-ance which can bring in other musical elementsthat are harder o grasp; n other words, the phe-nomenon of sound can be all-inclusive.PA: Haveyou everhad difficulty onvincingrchestradirectorso performCarter'sworks,particularlynAmerica?PB: Ah, but if I'm sure about something, I don'tcarewhat anyone thinks:I do it anyway I knowhow difficultI myselfhave found these works andI'm in direct contact with them, so I don't takeoffence at difficultiesexperiencedby others...PA: Onehasthefeeling hat Cartertandsoutside hetraditional comparisonbetween SchoenbergandStravinskyand, by extension,betweena state ofheightenedubjectivitynd a typeofmusicalbjectivity,as Adornoonceexpressedt...PB: Quite simply I believe that Carter has littlein common with the German radition.He trainedin Europe under Nadia Boulanger, in otherwords under Stravinsky's utelage, without anycontact at all with the German tradition. Hetotally rejected Wagnerism andRomanticism, asdid composerslike Stravinskyor Milhaud. Evennow, it isn't easy to persuade him to go andlisten to a Mahler symphony He doesn't likemusic like that. He regardsit as a completelyalien mode of expression.PA: But, paradoxically, e has developed feelforlarge-scaleformshichdoesn'tfallwithin the Frenchtradition...PB: Yes, but he doesn't structure these forms inthe same way: his works have no Durchfuhrung,in the strictsense of the word;there areno themesopposing, complementing or distorting each

other. His formal structure s based on intervals,on tempo, on categoriesthat don't form part ofthe German tradition.He developed his style indeliberateignorance of the German tradition oras a rejection of it, not only with all its faultsbutalso with all its qualities.PA: Yourmusicusuallycontains estures hat imme-diatelyreveal the structures;Carter'smusic on thecontrary s linked to characteristicsssociatedwithintervals, hythms nd instruments...PB: The idea of dramatizing the instrumentaldiscourse,the concept of instrumental haracters,can already be found in baroque music. Forexample,in Bach's sixth Brandenburgoncerto,ouhave various different and variableinstrumentalgroups, with dialogues between the groups anddifferentcombinations.Carterhas,fundamentally,the same approachto groups as certainbaroquecomposers.In hiswork, the groupsare establishedonce and for all and there are exchanges, as in agame of draughts, when you take one piecewith another. This also points to a difference ofapproach between us. I would actually find itvery difficult to begin a composition with a pre-determinedgroup, except in chambermusic, ofcourse. When confronted by an orchestra,I cansee an infinite number of possible combinationsand I don't like focusing on one over another.PA: Doesn't thisconceptualifferencetem,in Carter'scase,roma styleofwriting ased n expansivemelodiclines?PB:Yes, but you can clothe a long melodic linein a variety of different sounds Take the'Recitative' from Schoenberg'sPiecesforOrchestraopus 16, or Erwartung,or example. Obviously,this createsproblems with regardto weight andbalance which are difficult to solve in a practicalmanner. Carter adopted this principle inPenthode,at least partially. For my part, I findSchoenberg's orchestra around the period ofErwartungery appealing:t is highlydifferentiatedand, at the same time, very dangerous, becausethere is a huge dividebetween the instrumentalistswho are playing the same chord both withoutbeing able to prepare n advance, since the con-figurations change constantly, and withoutbeing able to make corrections after the event.There are moments of conflict between thesecontinual transformations and moments ofgreater stability,such as the interlude at the endof the first scene of Erwartung.This dramaticeffect,suspendedbetween order andchaos,whichSchoenberg could have developed even further,was used by Carter as a formal organizationalelement. In his Concerto for Orchestra, forexample, there are 'chaotic' moments harmoni-cally speaking that are extremely difficult to

This content downloaded from 134.10.132.57 on Sun, 9 Mar 2014 20:45:26 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/12/2019 Boulez on Carter

6/6

6 PierreBoulez in Intewiew II):on ElliottCarter, acomposer hospursme on'master because no one combination is moreimportant or more compelling than another.This means there are no longer any poles. Ithink his most recent works demonstrate awonderful resolution of this dialectic betweenorder and chaos.PA: Would t befeasibleosaythatCarters more kintoyou than mostcomposersy dintof his challenginglanguage ndcraftsmanship?

PB: Yes, absolutely,and that is probably he reasonI've performed his work so often: his musicdoesn't do anything for effect, he has no needfor distractions.He is a composer who makesme think about the present, about fundamentalissues;he spursme on and makes me questionwhat I'm doing. In this respect, I'd even go sofar as to say that he's one of the few composersI find interesting(This interview forms the preface to the symposiumElliottCarter,ou le tempsfertiledited by Max Noubel- the first volume in French devoted to Carter and hismusic - recently published by Editions Contre-champs, and has been translated for Tempoby kindpermission.)

Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Limited

Elliott arterNew worksCello Concerto (2000) 20'forcello and orchestraWorldpremiere:27 September 2001Symphony Hall,Chicago Yo-YoMa,Chicago Symphony Orchestraconducted by Daniel BarenboimOtherperformances:28/29 September, Chicago28 October, Carnegie Hall,New YorkForan interviewwith ElliottCarteraboutthe newconcerto,please visitourwebsiteatwww.boosey.com/publishing

Oboe Quartet (2001)for oboe and string trioWorldpremiere:2 September 2001St Mattheuskirche, LucerneHeinz Holliger,Thomas Zehetmair,Ruth Killiusand Thomas Demenga

17'

Thisperformances partof a Carter eatureatthe LucerneFestival, lso including:Partita,AllegroScorrevole,AskoConcerto,Oboe Concerto,Quintet orPiano andWinds,Quintet orPiano and StringsFordetailsvisit www.lucernemusic.ch/

BOOSEY HAWKES295 Regent Street, London W1R 8JH Tel: 020 7580 2060 Fax: 020 7637 3490III IIIIIIIIIIIIII

This content downloaded from 134.10.132.57 on Sun, 9 Mar 2014 20:45:26 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp