Beyond city limits - WordPress for Faculty & Staff · Beyond city limits A conceptual and political...

Transcript of Beyond city limits - WordPress for Faculty & Staff · Beyond city limits A conceptual and political...

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found athttp://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ccit20

Download by: [Clark University], [Mark Davidson] Date: 18 February 2016, At: 09:21

Cityanalysis of urban trends, culture, theory, policy, action

ISSN: 1360-4813 (Print) 1470-3629 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ccit20

Beyond city limits

Mark Davidson & Kurt Iveson

To cite this article: Mark Davidson & Kurt Iveson (2015) Beyond city limits, City, 19:5, 646-664,DOI: 10.1080/13604813.2015.1078603

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2015.1078603

Published online: 07 Oct 2015.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 356

View related articles

View Crossmark data

Beyond city limitsA conceptual and political defense of ‘thecity’ as an anchoring concept for criticalurban theory

Mark Davidson and Kurt Iveson

With the publication of their piece ‘Towards a New Epistemology of the Urban?’ in City19 (2–3), Neil Brenner and Christian Schmid hoped to ignite a debate about the ade-quacy of existing epistemologies for understanding urban life today. Brenner andSchmid’s desire to set urban research on a new course is premised on a wide-ranging cri-tique of ‘city-centrism’ that they believe is holding back both mainstream and criticalurban research. In this paper, we challenge Brenner and Schmid’s call for urbantheory to shift from a concern with cities as ‘things’ to a concern with processes of con-centrated, extended and differentiated urbanization. In their justified desire to critique‘urban age’ ideologies that treat ‘the city’ as a fixed, bounded and replicable spatialunit, Brenner and Schmid risk robbing critical urban theory of a concept and an orien-tation that is crucial to both its conceptual clarity and its political efficacy. We offer inits place a conceptual and political defense of ‘the city’ as an anchor for a criticalurban studies that can contribute to emancipatory politics. This is absolutely not a callfor a return of bounded, universal concepts of ‘the city’ that have rightly been thetarget of critique. Rather, it is a call for an epistemology of the urban that is foundedon an engagement with the political practices of subordinated peoples across a diverserange of cities. For many millions of people across the planet, the particularities of citylife continue to be the context from which urbanization processes are experienced, under-stood, and potentially transformed.

Key words: urbanization, urban age, the city, planetary urbanization, critical urban theory,urban politics

‘This book opens with a city that was,symbolically, a world: it closes with a worldthat has become, in many practical aspects,a city.’ (Mumford 1966, xi; opening sentenceto The City in History)

A new urbanism?

Since the 1980s, a debate over the epis-temological and political status of thecity has been simmering (e.g. Brenner

# 2015 Taylor & Francis

CITY, 2015VOL. 19, NO. 5, 646–664, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2015.1078603

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cla

rk U

nive

rsity

], [

Mar

k D

avid

son]

at 0

9:21

18

Febr

uary

201

6

2009; Massey 2007; Massey, Allen, and Pile1999; McFarlane 2011; Robinson 2006). Inthe past couple of years, this simmer hasreached boiling point. A number of urbantheorists (Brenner 2014; Brenner andSchmid 2014, 2015a, 2015b; Harvey 2014;Merrifield 2014) have developed theconcept of planetary urbanization to pushurban theory onto a new trajectory. Theforemost proponents of planetary urbaniz-ation have been Neil Brenner and ChristianSchmid (2015a). In a recent issue of City,they published an extensive paper that pro-vided the most forthright and developediteration of the planetary urbanizationthesis yet. While not necessary congruouswith the previous iterations of others (e.g.Harvey 2014; Merrifield 2014), the paperdoes develop an extended argument aboutthe implications of planetary urbanizationfor epistemologies of the urban.

For Brenner and Schmid (2015a), urbantheory now requires fundamental rethink-ing. The foundational concepts of urbantheory, most notably ‘the city’, must berevisited if urban theory is to respond tothe ‘rapidly changing geographies of urban-ization and urban struggle under early 21st-century capitalism’ (151). One can onlyagree with the sentiment. Whether viewedfrom the perspective of a global economiccrisis instigated by localized propertymarket financing or the formation of politi-cal movements across space via social media(Mason 2013), concepts such as ‘the city’ or‘the urban’ appear to have more and moreintellectual labor to perform.

Brenner and Schmid’s (2015a) recentintervention is therefore timely and necess-arily provocative. In their paper, they statetheir desire for the work to ‘ignite andadvance further debate on the epistemologi-cal foundations for critical urban theory andpractice today’ (151). Based alone on thecritical reflections of Richard Walker (2015)in the same issue, they clearly succeeded.This stated, in a response to Walker’s piece,Brenner and Schmid (2015b) argue thatWalker’s polemic commentary caricatured,

misrepresented and misunderstood theirwork. In picking through Walker’s criti-cisms, they conclude that there are actuallyfew areas of substantive disagreementbetween their respective positions.

In an effort to avoid missives or countingthe angels dancing on the head of a pin, thispaper seeks to examine some of the mostfundamental and challenging aspects ofBrenner and Schmid’s (2015a) planetaryurbanization thesis.1 Our engagement ismotivated by our own ongoing attempt tograpple with the form and utility of criticalurban theory (Davidson and Iveson 2014a,2014b). In this work, we have attempted toapproach urban theory by giving primacyto politics. This has involved an explicitattempt to formulate critical urban theorythat avoids becoming another variant thatproduces a critical orientation without pro-viding any ability to transcend critique(Davidson and Iveson 2014a, 4). We takethe same approach in this engagementwith planetary urbanization debates.

Our starting point—our epistemologicalfoundation—is therefore different fromBrenner and Schmid’s (2015a). It is worthnoting the implications of such differences.When we set out to develop concrete concep-tualizations of the urban, we necessarilyabstract something from the vast indetermin-able set of processes that make up our crude‘urban’ reality. How we perform this abstrac-tion, that is, what pieces of reality we chose toplace in our intellectual gaze, creates the effectof constructing the very object we seek tounderstand. We must therefore be mindfulof how we begin the process of epistemologi-cal abstraction—our foundations and startingpoints—since we will have to live with theimplications of these later on; and particularlywith respect to what political utility we findwithin our critical urban theory.

Our goal here is to argue that planetaryurbanization needs to be recast and re-approached, and to argue for the ongoingimportance of ‘the city’ as a key categoryfor critical urban theory. As urban theoristsare impelled to understand how ‘the erstwhile

DAVIDSON AND IVESON: BEYOND CITY LIMITS 647

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cla

rk U

nive

rsity

], [

Mar

k D

avid

son]

at 0

9:21

18

Febr

uary

201

6

boundaries of the city . . . are being explodedand reconstituted’ (Brenner and Schmid2015a, 154), there is much to be gained froman engagement with the idea of planetaryurbanization. Yet we must pump the brakesa little. While there is a great deal of the newto be explained, our eagerness to understandnovelty must not blind us to that which per-sists. Further, we worry that in their justifieddesire to critique ‘urban age’ ideologies thattreat ‘the city’ as a fixed, bounded and replic-able spatial unit, Brenner and Schmid riskrobbing critical urban theory of a conceptand an orientation that is crucial to both itsconceptual clarity and its political efficacy.

Our paper proceeds in three sections. First,we outline a key aspect of Brenner andSchmid’s planetary urbanization thesis: theircritique of ‘cityism’ in urban studies. In thefollowing two sections, we offer two correc-tives to this critique of cityism. First, wesuggest that there are conceptual limitationsin Brenner and Schmid’s critique of cityism,and argue that the category of ‘the city’requires a more thorough dialectical re-exam-ination. This conceptual discussion is necess-arily pretty ‘academic’—but this engagementis important precisely because of the relation-ship between the way we think and the waywe act. In the third section, we spell outwhat we believe are the problematic politicalimplications of Brenner and Schmid’s epis-temology. Here, we argue that critical urbantheory must begin with the political if it isto accomplish its objectives, and set outhow a theory of planetary urbanization canhelp us to develop a method of equality(Davidson and Iveson 2014b) that under-stands the democratic utility of the city toan emancipatory politics. In conclusion, wereflect on the nature of debate over planetaryurbanization and the implications of itstenure.

‘Cityism’

‘So it goes, in a world that knows no realborders yet seems everywhere to build walls.

Planetary urbanization, as such, both unitesand divides the world, unites and divides itsplanetary citizens.’ (Merrifield 2014, xi)

‘ . . . we aim to advance a hitherto largelysubterranean stream of urban research thathas, since the mid-twentieth century, castdoubt upon established understandings of theurban as a bounded, nodal and relatively self-enclosed socio-spatial condition’. (Brenner2014, 15)

As the above quotations illustrate, the plane-tary urbanization thesis is concerned with anexamination of the boundaries and implieddivisions imposed by ‘the city’. Thisconcern with the persistent impositions of‘the city’ is central to Brenner and Schmid’s(2015a) sweeping critique of existing urbantheory. They argue that ‘the city’ hasenjoyed a bit of a revival in both scholarshipand policy—the widely repeated mantra thatmore than half the world’s population nowlives in cities has given rise to a plethora ofresearch seeking to understand the urbanizedhuman condition, not to mention an ‘urban-ologizing’ of mainstream science and econ-omics (see also Gleeson 2012).

The effect of this type of research andassociated theory, Brenner and Schmid(2015a, 165) argue, has often been to reducethe urban to a ‘universal form’, a ‘settlementtype’ or a ‘bounded spatial unit’. While theuse of such statistics on urban populationsis almost by definition misleading and opento manipulation (see Satterthwaite 2003), thewidespread application of the heuristic hasundoubtedly given rise to a proliferation ofspatial imaginaries that construct the idea ofpeoples moving into city spaces (e.g.Glaeser 2011; Saunders 2010).

The problematization of urban theorythat approaches the city as bounded has, ofcourse, been with us for an extendedperiod. In recent years a host of urban scho-lars have attempted to understand the city asa relational space (e.g. Amin and Thrift2002; Massey, Allen, and Pile 1999; Shep-pard, Leitner, and Mariganti 2013). A widerange of research agendas have demon-strated the ways in which cities are shaped

648 CITY VOL. 19, NO. 5

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cla

rk U

nive

rsity

], [

Mar

k D

avid

son]

at 0

9:21

18

Febr

uary

201

6

through, for example, processes of economicand cultural globalization (e.g. Holston1999; Isin 2001; Sassen 2001), migration(e.g. Sandercock 2002) and the metaboliza-tion of environmental resources (e.g.Heynen, Kaika, and Swyngedouw 2006).These investigations have been accompaniedby a host of theoretical developments, manyof which have drawn on postcolonial the-ories and/or actor-network and assemblagetheories to propose new ways to study andexplain urban life (e.g. Farıas and Bender2012; McFarlane 2011; Robinson 2006; Royand Ong 2011; Sheppard, Leitner, and Mar-iganti 2013). In most cases, this has involveda rethinking of what makes, and what is,‘the city’.

Although the import of innovative socialtheory into urban studies has stimulated agreat deal of novel empirical work andrelated re-theorization, it is important tonote that relational understandings of citiesand urbanization have long influenced criticalurban studies. Indeed, in the very first issue ofCity, in a piece recently included in ananthology on planetary urbanization com-plied by Brenner and Schmid (2014), DavidHarvey (1996, 50) argued that ‘the “thing”we call a “city” is the outcome of a“process” we call “urbanization”’. Inmaking ‘the city’ a product of urbanization,the former necessarily became hitched to geo-graphically dispersed social and economicprocesses:

‘Urbanization must then be understood not interms of some socio-organizational entitycalled “the city” (the theoretical object that somany geographers, demographers andsociologists erroneously presume) but as theproduction of specific and quiteheterogeneous spatio-temporal formsembedded within different kinds of socialaction.’ (Harvey 1996, 52)

Harvey here repeats a spatial ontology articu-lated in his groundbreaking 1973 SocialJustice and the City that placed an emphasison the relationship between social processand spatial form (e.g. Harvey 1973, 13–14).

However, Brenner and Schmid (2015a) areasking us to take a conceptual leap beyondexisting approaches to urban studies thatpractice relational thinking. They want us todispense with ‘the city’ as an anchoringconcept for urban theory. Early in theirpiece, they pose the following provocativequestions:

‘If the urban is no longer coherentlycontained within or anchored to the city—or,for that matter, to any other boundedsettlement type—then how can a scholarlyfield devoted to its investigation continue toexist? Or, to pose the same question as achallenge of intellectual reconstruction: isthere—could there be—a new epistemologyof the urban that might illuminate theemergent conditions, processes andtransformations associated with a world ofgeneralized urbanization?’ (Brenner andSchmid 2015a, 155)

In this passage and others like it, Brenner andSchmid call into question the place of ‘thecity’ itself in urban theory. Drawing onLefebvre’s characterization of urbanizationas a process of implosion and explosion(Brenner 2014, 17), they suggest instead thatwe embrace an epistemology that seeks tounderstand the production of various kindsof ‘urban fabric’ that stretch beyond ‘thecity’ and across the planet through momentsof concentrated, extended and differentiatedurbanization. Importantly, it is not justnon-relational approaches to the city thatare in the firing line. Brenner and Schmidare not only critical of contemporary ‘urba-nology’ produced by the likes of EdwardGlaeser (2011)—they are also critical ofsome of the strands of urban theory thathave insisted on a relational approach tocities and cityness, on the grounds that theyare still characterized by a ‘stubbornly per-sistent “methodological cityism”’ (Brennerand Schmid 2015a, 162). It is no longerenough, they argue, to contest problematicideologies of the city as a bounded, universalspatial by offering an ‘alternative, substan-tially reinvigorated interpretive framework

DAVIDSON AND IVESON: BEYOND CITY LIMITS 649

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cla

rk U

nive

rsity

], [

Mar

k D

avid

son]

at 0

9:21

18

Febr

uary

201

6

through which to investigate its production,evolution and contestation’, as critical urba-nists have done in the past. The fault withthis approach is that it persists in ‘viewingthe unit in question—the urban region oragglomeration—as the basic focal point fordebates on the “urban question”’ (154).

‘Methodological cityism’ is a term bor-rowed from Angelo and Wachsmuth’s(2015) critique of how the ‘urban’ is concep-tualized in the urban political ecology litera-ture. Angelo and Wachsmuth claim urbanpolitical ecology has lacked a completedengagement with Lefebvre’s theorization ofurbanization. Thus, too much urban research‘takes as its methodological premise the cityas a site as opposed to urbanization as aprocess’ (Angelo and Wachsmuth 2015, 21).This methodological problem has ‘natura-lized the city as the sole analytical terrain ofurban analysis’ (21). They argue for a

‘return to Lefebvre’s ([1970] 2003, 57)contention that “the city no longercorresponds to a real social object”, and thatthe proper object of analysis for urban studieswould soon have to become a world-wideurban society exploding out of the historicalspace of the city’. (Angelo and Wachsmuth2015, 23)

Building on Angelo and Wachsmuth’s cri-tique of urban political ecology, Brennerand Schmid argue that the problem of meth-odological cityism can also be identified inmuch contemporary postcolonial urbanresearch. Within this literature they arguethat there is a ‘tendency to treat “the city”as the privileged terrain for urban research’(Brenner and Schmid 2015a, 162). Whilemuch of this literature is ‘attuned to the mul-tiple sociospatial configurations in whichagglomerations are crystallizing under con-temporary capitalism’ (162) it is ultimatelyproblematic since ‘the bulk of postcolonialurban research and theory-building has, inpractice, focused on cities, tout court’ (162).Even relational approaches to ‘the city’,then, are not enough—from this perspective,an adequately processual approach to the

urban would dispense with ‘city-centric epis-temologies’ (169), thereby displacing ‘thecity’ from its central role in urban theory,research and practice.

This further conceptual leap seems to us tobe misconceived. In distinction to Brennerand Schmid (2015a, 2015b), we think that‘the city’ remains a vital anchoring point forcritical urban theory, so long as it is kept inproductive tension with a concept of ‘theurban’ that is not contained within it. In thetwo sections to follow, we outline tworelated sets of concerns with the planetaryurbanization thesis proposed by Brennerand Schmid—conceptual and political.

Conceptual limitations: revisiting the city/urban dialectic

The critique of ‘the city’ and the persistenceof ‘methodological cityism’ or ‘city-centrism’in urban studies is a defining element ofBrenner and Schmid’s proposed epistem-ology, and it has been one of the most conten-tious aspects of their work. (Indeed, weshould not be surprised that it might generatecritical responses from readers and authors ofa journal called City!) Their treatment of ‘thecity’ is therefore worth unpacking in somedetail.

Certainly, Brenner and Schmid do main-tain a concern with agglomeration. Their tri-partite framework for enquiry into the‘moments and dimensions of urbanization’includes a focus on processes of ‘concentratedurbanization’ that involve agglomeration andspatial clustering of populations, activitiesand infrastructures. However, they do seeka ‘systematic analytical delinking of urbaniz-ation from trends related exclusively to citygrowth’ (Brenner and Schmid 2015a, 169).

There appear to us to be two variations onthis ‘analytical delinking’ of urbanization andcities in Brenner and Schmid’s recent work—a provocative and a more modest version.When stated most strongly and provoca-tively, their epistemology of the urbanseems to have no place at all for a concern

650 CITY VOL. 19, NO. 5

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cla

rk U

nive

rsity

], [

Mar

k D

avid

son]

at 0

9:21

18

Febr

uary

201

6

with ‘the city’ or ‘cities’. To take planetaryurbanization seriously demands a substantialepistemological break with existingapproaches (both mainstream and critical).In this strong version of their thesis, theanalytical delinking of urbanization fromcities is premised on two related epistemo-logical claims:

(a) claim about the non-existence of cities asbounded things, and in favor of a proces-sual approach to urbanization, includingprocesses of agglomeration, and;

(b) the non-existence of a non-urban‘outside’ to cities, and in favor of aconcept of ‘planetary urbanization’whose ‘urban fabric’ includes eventhose erstwhile rural and wildernessspaces that are now put to work in theservice of ‘the relentless growth impera-tives of an accelerating, increasingly pla-netary formation of capitalisturbanization’ (Brenner and Schmid2015a, 153).

Therefore, there are processes of ‘concen-trated urbanization’ alongside other urbaniz-ation processes, and ‘the “power ofagglomeration” remains as fundamental asever’ (Brenner and Schmid 2015a, 154).However, they insist that the moments ofurbanization, including ‘concentrated urban-ization’ and agglomeration, do not refer to‘distinct morphological conditions, geo-graphical sites or temporal stages, but tomutually constitutive, dialectically inter-twined elements of a historically specificprocess of sociospatial transformation’ (169).

In this stronger version of their argument,Brenner and Schmid seek to displace anynotion of cities as ‘things’ with a notion ofagglomeration as process. In this respect, wethink Brenner and Schmid’s provocative pla-netary urbanization thesis contains momentsof over-reach. They problematically pushbeyond the justified (and widely accepted)notion that urbanization processes exceedany fixed things called ‘cities’ to a claim thatit is no longer even meaningful or useful to

talk or think about ‘the city’ as a particularkind of ‘thing’ at all. The dialectic of‘things’ (i.e. cities) and ‘social processes’ (i.e.urbanization) that Harvey recommendsabove is replaced with a dialectical relation-ship between processes (i.e. ‘moments’ ofconcentrated, extended and differentiatedurbanization—see, especially, Brenner andSchmid 2015a, 166–169). Here, we concurwith one of Walker’s (2015, 185) criticisms:

‘Yes, the urban is a process, but it is also anobject. Too many times recently I’ve seenheard [sic] scholars declare, in all seriousness,that something is a process and not a simplething. This is not a great insight; in fact, it’s ahalf truth. . . . I agree we cannot approachcities as naıve empiricists for whomsettlement types or boundaries are simple andself-evident, nor urban forms unchangingover time. But to declare everything asprocess and all form as forever shape-shiftingis thoroughly one-side. Where are thedialectics here? Where is the materialism?’

We think any outright rejection of ‘the city’as a thing towards which urban theorymight be oriented is conceptually flawed.Sure, as Walker notes, if ‘the city’ is con-ceived of as a bounded morphological formalone, then Brenner and Schmid’s (2015a)thesis seems plausible. However, as theyreadily admit, many who persist with someform of ‘methodological cityism’ wouldreject a notion of ‘the city’ as a ‘universalform’ or ‘bounded spatial unit’. Even in theChicago School theorists, used by Brennerand Schmid (2015a) as an example of thetype of urban theory that requires transcen-dence, we find multivariate definitions ofthe city that connect morphology to otherfeatures with extended geographies. Wirth(1938) argued that the city is defined by (i)permanence, (ii) large population size, (iii)high population density and (iv) social het-erogeneity. Here then, ‘the city’ concept isdoing more work than simply dealing witha fixed, bounded and/or universal urban mor-phology. (And as we will argue below, anurban theory that does not relegate ‘the

DAVIDSON AND IVESON: BEYOND CITY LIMITS 651

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cla

rk U

nive

rsity

], [

Mar

k D

avid

son]

at 0

9:21

18

Febr

uary

201

6

city’ to junior partner status is importantwhen dealing with the political componentsof social heterogeneity.)

Brenner and Schmid’s (2015a) assertionthat even a critical and relational orientationtowards ‘the city’ should be replaced by aprocess-based understanding of the geogra-phy of urbanization (i.e. a dialectic betweenconcentrated and extended urbanization)over-simplifies ‘the city’ concept. AsHarvey (1973) argues, it is quite possible toincorporate multiple spatialities into urbantheory. Indeed, for Harvey (1973), it isnecessary to incorporate multiple spatialitiesinto urban theory precisely because this mul-tiplicity exists in our experience of the world:

‘space is neither absolute, relative or relationalin itself, but it can become one or allsimultaneously depending on thecircumstances. The problem of the properconceptualization of space is resolved throughhuman practice with respect to it. In otherwords, there are no philosophical answers tophilosophical questions that arise over thenature of space—the answers lie in humanpractice.’ (13)

The city should therefore be understood as acentrally important, multi-dimensionalconcept within urban theory. Furthermore,urban theory must be responsive to the factthat ‘the city’ remains a significant categoryof our ideology; it is used to bracket, invarious ways, the planetary urbanization weall live with. ‘The city’ is multiple things,such as an object, a political boundary, ageography identity, a brand, a community, aunit of collective consumption, and more. Aterm such as ‘London’ therefore refers to anobject with multiple socio-spatial configur-ations which, in ways not always directlytied to the said object, have various generativeaffects. The prospective replacement of ‘thecity’ with a processional spectrum ofextended/concentrated urbanization there-fore strips urban theory of the necessity toinvestigate the implications of a socialsystem based around, while not fully con-tained within or defined by, agglomeration.

The difficulties of doing without a notionof cities as ‘things’ that exist in relation toprocesses of urbanization is evidenced insome of the semantic acrobatics thatBrenner and Schmid (2015a) end up perform-ing in an attempt to discuss ‘concentratedurbanization’ without any use of the ‘c’word. Terms such as ‘large-scale metropoli-tan centers’ (Brenner and Schmid 2015a,166), ‘spatial clusters’ (166), ‘large agglomera-tions’ (167), ‘dense population centers’ (167)and ‘large urban centers’ (168) are used torefer to the ‘places formerly known ascities’.2 Here, in making their point aboutthe diverse geographies of urbanization andthe diverse forms of ‘urban fabric’ that areproduced, they end up substituting termsand maintaining concepts.

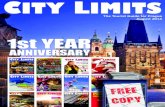

This substitution of terms also character-izes the grid provided by Brenner andSchmid to illustrate the core elements oftheir epistemology of the urban. In theirgrid (Figure 1), Brenner and Schmid (2015a)divide the different geographies of urbaniz-ation in order to sketch out the variousforms of urban fabric that have envelopedthe planet. We find a great deal of their inter-pretative matrix to be very useful for under-standing today’s urbanisms. However, theidea of ‘concentrated urbanization’ thatforms the top row of their grid is, we think,simply another way to talk about ‘cities’.Indeed, the idea of ‘[T]he production ofbuilt environments and sociospatial configur-ations to harness the power of agglomeration’(Brenner and Schmid 2015a, 171) provides aquite concise definition of the things we call‘cities’. We also think that much of whatthey seek to capture in the bottom row as‘differential urbanization’ refers to changestaking place in places we can describe ascities. For example, reference to ‘[R]ecurrentpressures to creatively destroy inherited geo-graphies of agglomeration and associatedoperational landscapes’ (171) is another wayto articulate the processes of (re)investmentwithin urban land markets. This substitutioncan only be justified if references to ‘the city’are so reductive that they serve to obfuscate

652 CITY VOL. 19, NO. 5

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cla

rk U

nive

rsity

], [

Mar

k D

avid

son]

at 0

9:21

18

Febr

uary

201

6

the differentiated forms of urbanization. Yetconceptualizations of ‘the city’ have alwayscarried with them multiple components, justas the concept of urbanization continues todo in Brenner and Schmid’s (2015a)formulation.

In its more modest articulations, Brennerand Schmid’s epistemology seems not todemand an outright rejection of the ideathat there are such things as ‘cities’. Rather,there seems to be an acknowledgement that‘cities’ exist, but only as one among manykinds of ‘urban fabric’ associated with theplanetary processes of urbanization. In‘Thesis 3’ on the three mutually constitutivemoments of urbanization, they note that

‘Obviously, large agglomerations remaincentral arenas and engines of massive urbantransformations, and thus clearly merit sus-tained investigation, not least under early21st-century capitalism’ (Brenner andSchmid 2015a, 167). They go on to arguethat it is simply the orientation towardssuch agglomerations that must change:

‘However, we reject the widespreadassumption within both mainstream andcritical traditions of urban studies thatagglomerations represent the privileged oreven exclusive terrain of urban development(Scott and Storper 2014). In contrast, wepropose that the historical and contemporarygeographies of urban transformation

Figure 1 Moments and dimensions of urbanization, from Brenner and Schmid (2015a, 171)

DAVIDSON AND IVESON: BEYOND CITY LIMITS 653

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cla

rk U

nive

rsity

], [

Mar

k D

avid

son]

at 0

9:21

18

Febr

uary

201

6

encompass much broader, if massivelyuneven, territories and landscapes, includingmany that may contain relatively small,dispersed or minimal populations, but wheremajor socioeconomic, infrastructural andsocio-metabolic metamorphoses haveoccurred precisely in support of, or as aconsequence of, the everyday operations andgrowth imperatives of often-distantagglomerations. For this reason, the momentof concentrated urbanization is inextricablyconnected to that of extended urbanization.’

The city is not rejected per se, it is rejected asa ‘privileged or even exclusive terrain ofurban development’. Urban theory needs tobe less ‘city-centric’, and pay more attentionto those extended elements of urbanizationthat occur in relation to concentrated urban-ization: ‘the moment of concentrated urban-ization is inextricably connected to that ofextended urbanization’. Here ‘the city’returns (sort of), in the form of concentratedurbanization where ‘agglomeration’ is thingas well as process.

The more modest critique of ‘city-cen-trism’ also characterizes parts of Brennerand Schmid’s response to Walker. There,they appear to pull back a little from themore provocative, stronger variation of theirepistemology with its determined avoidanceof ‘the city’. In place of outright rejection ofthe term, they mobilize it to describe a par-ticular kind of morphology that exists along-side others in the process of planetaryurbanization:

‘While we do not deny the connectionbetween urbanization and city-building(agglomeration), we view the latter as onlyone among many morphological patterns thatare associated with the urbanization process.’(Brenner and Schmid 2015b, 10)

Here, then, rather than jettisoning the cityconcept altogether, they draw the city/urban distinction, and further argue that weshould place most of the intellectual emphasison urbanization: ‘because we emphasizeprocess rather than morphology, the

parameters for a definitional specification ofthe urban (as well as of urbanization) arereframed’ (Brenner and Schmid 2015b, 10).This intellectual emphasis, they argue, givesgreater purchase on the diverse geographiesof urbanization:

‘Our work to date gives us reason to believethat significantly expanded notions of theurban and urbanization do indeed open upsome useful, productive new horizons forengaging with contemporary sociospatialtransformations.’ (10)

What is ‘new’ here is more a matter of empha-sis than a matter of breaking with existingrelational epistemologies. An orientationtowards ‘the city’ or ‘cities’ is thought toinhibit our ability to further develop an epis-temology of the urban that insists on pro-cesses and relationships that extend beyondthe city limits.

Therefore, there is an ambiguity inBrenner and Schmid’s treatment of ‘thecity’ and ‘cities’ that has important impli-cations for their epistemological claims. Webelieve it is quite possible to strongly agreewith the notion that urbanization processesextend beyond ‘the city’ (perhaps even to aplanetary scale), while strongly disagreeingwith the notion that ‘the city’ either doesnot exist or that its theoretical mobilizationis so limiting that it should be jettisonedand replaced by a notion of concentrated/extended urbanization. Brenner and Schmid(2015b) are critical of Walker for insistingthat ‘the “city” and the “urban” are essen-tially identical concepts’. While we are notsure he actually does this, we certainlyagree with them that it is important to main-tain a distinction between ‘the city’ andurbanization. However, for us this distinc-tion should not over-ride their fundamentalrelation as things and processes. As Harvey(1996, 50) put it, while it is important notto fall into the ‘persistent habit of privilegingthings and spatial forms over social pro-cesses’, that does not mean dropping theentire notion of ‘things’ like cities:

654 CITY VOL. 19, NO. 5

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cla

rk U

nive

rsity

], [

Mar

k D

avid

son]

at 0

9:21

18

Febr

uary

201

6

‘The antidote is not to abandon all talk of thecity as a whole, as is the penchant ofpostmodernist critique, but to return to thelevel of social processes as being fundamentalto the construction of the things that containthem.’ (51)

Without some reference to ‘cities’, we find itdifficult to understand what is distinctly‘urban’ about some of the socio-spatial pro-cesses and forms that Brenner and Schmidseek to highlight. Let us be clear, this is absol-utely not to suggest that the urban is the sameas ‘the city’, and/or that the urban is con-tained within the city. Nor do we think thatis the only geographical expression of urban-ization. However, we would argue that thegeographies of ‘extended urbanization’ high-lighted by Brenner and Schmid can only bemeaningfully understood to be urban (or toproduce a kind of ‘urban fabric’) in relationto cities. That is to say, the geographies ofurbanization that extend beyond cities areurban because of their relation to unfoldingprocesses of city-making. If the extendedgeographies of urbanization have no necess-ary or privileged or significant relation tocities, then what makes them urban? Wewould insist on a reading of the ‘city/urbandistinction’ that maintains a focus on both,keeping some relational notion of ‘cities’and ‘cityness’ as an anchor for an ‘epistem-ology of the urban’. Without that anchoringnotion, why consider any of the processeslisted through the lens of the urban at all? Itis possible to organize our enquiries intocities in a manner that extends far beyondthe city limits (see Brenner and Schmid2015b, 10) while nonetheless maintainingsome sense of cityness that is distinct from,while related to, other spatial formations.

Like Walker, we prefer to approach therelationship of ‘the city’ and ‘the urban’within urban theory as a dialectic of ‘thing’and ‘process’ (see also Lefebvre 1991; Merri-field 2002). We agree with Brenner andSchmid (2015a) that in recent decades, theconcept of ‘the city’ seems to have diminishedin utility, while ‘the urban’ has become a

critical concept for understanding life acrossthe planet (see Lefebvre 1991, [1970] 2003).However, we cannot agree that this centraldialectic of urban theory has disappeared, orthat we can replace it with a dialecticbetween processes of concentrated andextended urbanization without losingcrucial analytical and political purchase.Nor can we agree even with the moremodest version of Brenner and Schmid’sthesis that ‘the city’ should now, at best,play a bit part in urban theory development.Their suggested conceptual realignmentaway from ‘the city’ as a ‘thing’ runs therisk of removing the necessary city/urbandialectic of urban theory.

We might translate the extended planetaryurbanization thesis of Brenner and Schmid(2015a) as claim that urban theory hasreached a transcendent moment that hasmade ‘the city’ into a largely redundantconcept:

‘In contrast to the geographies of territorialinequality associated with previous cycles ofindustrialization, this new mosaic of spatialunevenness cannot be captured adequatelythrough areal models, with their typologicaldifferences of space between urban/rural,metropole/colony, First/Second/ThirdWorld, North/South, East/West and soforth.’ (Brenner and Schmid 2015a, 152)

Whereas ‘the city’ may once have definedwhere and how the urban occurs, now it isno longer necessary:

‘Indeed, rather than witnessing the worldwideproliferation of a singular urban form, “thecity”, we are instead confronted with newprocesses of urbanization that are bringingforth diverse socio-economic conditions,territorial formations and socio-metabolictransformations across the planet.’ (Brennerand Schmid 2015a, 152)

The urban therefore no longer requires thecity; urbanization no longer maps onto thecity form. It is more productive to view our(urbanized) society producing its own

DAVIDSON AND IVESON: BEYOND CITY LIMITS 655

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cla

rk U

nive

rsity

], [

Mar

k D

avid

son]

at 0

9:21

18

Febr

uary

201

6

particular spatiality, within which ‘cities’—ascritical and identifiable objects of agglomera-tion and from which people derivemeaning—exist and exert a power influenceover the entire social process. Yes, ‘cities’ isplural, and thus we could chose to definevarious ‘urban fabrics’ as opposed to various‘cities’. However, this would entail us losingan ability to define those spaces that can gen-erate urbanism itself. It is the production ofspatial logics within particular spaces(especially, for urban theorists, cities), thatgives rise to the evolution of the pro-duction(s) of space through planetary urban-ization. As Brenner and Schmid (2015a)argue, we may now live in a momentwhereby a particular mode of spatial appro-priation is dominant on a global level. Yet,if we follow our dialectical thinkingthrough, even this would not mean that ‘thecity’ itself disappears. Rather, we mightonly be able to understand the planetaryurban process through a re-engagementwith the idea of ‘the city’. Purging our voca-bulary of ‘the city’ would seem to be counter-productive to our dialectical thinking in thisregard.3

The politics of this reasoning is—poten-tially—fascinating. As well as focusing onthe planetary urbanization process—here weare thinking of the images of shipping lanes,tar sands and ocean cables that are mobilizedin planetary urbanization publications(Brenner and Schmid 2014)—we might actu-ally have to place our gaze back on ‘the city’to understand and politicize the current capi-talist spatial configuration. Think, forexample, about how the New York Times(Story and Saul 2015) in its recent series onwho owns what Manhattan apartments (i.e.the working of a very local propertymarket) illustrated the operation of corruptedglobal capitalism. It is only through under-standing a problematic city object (i.e. theNew York City real estate market) that onecan begin to see how, for example, sovereignwealth can be (ab)used by corrupt elites.Without understanding what Manhattan is,as a social and real estate locale, it is

impossible to fully understand part of thecurrent global capitalist process. In just thissingle example, it is possible to see how westill need to prioritize a particular part ofthe concentrated/extended urbanizationspectrum (i.e. the city) to understand howinherently localized agglomeration processesconnect into, and constitute, broader urban-ization processes.

We might consider Doreen Massey’s(2007) World City as an exemplar of criticalurban theory that is concerned with Londonas a city, without treating London as a‘fixed, bounded or universally generalizable’thing. Indeed, Massey’s book seeks preciselyto understand London in relation to broaderspatial processes that reach ‘beyond citylimits’, noting how it is shaped by (andindeed shapes) such processes. Even whileinsisting that one cannot draw a line aroundLondon, in passages such as the followingLondon is still referred to as a ‘place’, an‘it’, a ‘here’ and even potentially a ‘we’:

‘A high proportion of Londoners were bornoutside the administrative boundaries. But itis far more than this. There is a vast geographyof dependencies, relations and effects thatspreads out from here around the globe. Thisis not to slide into some easy declaration that“everyone is a Londoner”, but it is to arguethat, in considering the politics and thepractices, and the very character, of this place,it is necessary to follow also the lines of itsengagement with elsewhere. Such lines ofengagement are both part of what makes itwhat it is, and part of its effects.’ (Massey2007, 13)

Of course, Massey (2007, 14) also realizesthat such a view of London is not universallyshared, and that others continue to associatethe idea of the city with ‘closure, compe-tition, and the evocation of externalenemies’. However, to engage in a politicsthat contests such fixed, bounded construc-tions of London is not to reject the veryidea of London per se—just as we arguethat developing critical understandings ofurbanization and its various geographies

656 CITY VOL. 19, NO. 5

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cla

rk U

nive

rsity

], [

Mar

k D

avid

son]

at 0

9:21

18

Febr

uary

201

6

ought not proceed by rejecting the very ideaof the city as a thing. Massey conceives ofher project as ‘an argument against localismbut for a politics of place’—a politics that isnot contained within London, but rathertakes the form of a ‘politics of place beyondplace’ (15). Here, we think it would be amistake to treat Massey’s work (along withthe work of postcolonial urbanists andurban political ecologists) as a form of‘cityism’ that needs to be transcended. Cru-cially, Massey’s work also shows what is atstake politically in our defense of a (particularform of) cityism. As ever, Massey’s Londonwork is designed to help us conceptualizeand support emancipatory political praxis.This point is of particular significance for cri-tically oriented urban theory, of course.Therefore, let us now consider it in furtherdepth.

Political limitations: on the particular andthe universal in emancipatory urbanpolitics

Many of the powerful movements that haverocked the world in recent years have beenignited by efforts to intervene in the waysthat cities are regulated and lived—be it inrelation to the policing of informal urbantraders in Tunisia, the price of buses in Rio,the building of a shopping mall in centralIstanbul, the price of a living wage inLondon and Los Angeles, and so on. Thisshould surely tell us something. Of course,Brenner and Schmid (2015a, 153) are notignorant of such struggles. However, theepistemology they offer does not seem to usto live up to their stated desire to understandhow such struggles seek ‘not only to influ-ence the production of places, but toreshape the broader institutional and territor-ial frameworks through which urbanizationprocesses are being managed’ (153). Thecrucial point for us is that collective effortsto ‘influence the production of places’ areoften explicitly oriented towards ‘the city’(by which we mean they are emplaced

efforts to remake Sydney or Sao Paulo orSheffield), and this orientation towards thecity remains a crucial way in which a politicsof urbanization that potentially extendsbeyond ‘the city’ takes shape. That is to say,the very politics of urbanization which theor-ists such as Brenner and Schmid (2015a) andMerrifield (2014) seem to want has notemerged through a refusal of ‘the city’ infavor of an orientation towards ‘planetaryurbanization’—rather, it has emergedthrough struggles over life in cities that fre-quently mobilize ‘the city’ as their stage,their object and even their subject (see David-son and Iveson 2014a). Here, we agree withHarvey (1996, 58–59; emphasis added) onthe need to view:

‘the production of different spatio-temporalorderings and structures as active momentswithin the social process, the appreciation ofwhich will better reveal how what weconventionally understand by urbanizationand urban forms might be redefined andfactored in as moments of transformation andconsequently possible points of interventionwithin that social process’.

While cities, then, are not the only (or evenalways the primary) point of intervention inthe processes of urbanization, they remaincrucial and require very particular analyticaltreatment to understand their significance(i.e. an urban theory).

This political point about the shifting butenduring significance of ‘the city’ for anemancipatory urban politics emerges fromour conceptual discussion of the city/urbandialectic above. Politically, the problemwith the notion that we should dispensewith or demote ‘the city’ within urbantheory is this: by dismissing a concern withthe particularities of city life in favor of afocus on the universality of planetary urban-ization, Brenner and Schmid also shift ourfocus away from the particular places wherepolitical challenges to the abstract universal-ity of planetary urbanization might emerge.As critical urban theorists, if we were tofollow Brenner and Schmid’s (2015a) lead

DAVIDSON AND IVESON: BEYOND CITY LIMITS 657

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cla

rk U

nive

rsity

], [

Mar

k D

avid

son]

at 0

9:21

18

Febr

uary

201

6

we could become focused on the abstract uni-versality of planetary urbanization.However, we cannot simply read off the pol-itical from such analyses. This would be todisconnect the central dialectical of criticalurban studies: the relationship between thecity (as lived) and the urban process (as struc-ture). At a moment where the relationshipbetween these two things is clearly in flux,such an intellectual choice would seem totake critical urban studies in the wrongdirection.

At this point it is important to clarify ouruse of the term politics. We are not arguinghere that an (abstract) critique of urbanizedcapitalism is without some form of politics.The identification of exploitation, of anykind, within the Marxian-derived planetaryurbanization thesis demonstrates all kinds ofsocietal tension and relations. Yet this doesnot provide a foundation for understandinghow politics actually takes place. Here, inour recent work on urban politics (Davidsonand Iveson 2014a, 2014b; Iveson 2014), wehave turned to Jacques Ranciere to help usbetter understand how politics works, as anenacted practice of dissensus and disagree-ment. As we now seek to explain, we findRanciere’s approach to the relationshipbetween the universal and the particularespecially helpful in thinking through theimportance of ‘the city’ for a politics thatmight confront the inequalities and injusticesof planetary urbanization. Such a navigationis required for us to understand how a plane-tary urban process shapes, and is shaped by,the city. Without this, it is very difficult toachieve the political objectives of criticalurban theory.

Ranciere’s political theory has becomeincreasingly influential within critical urbanstudies in recent years (e.g. Dikec 2007,2013; Swyngedouw 2009, 2010). It is a littledifficult to pigeonhole Ranciere’s approachprecisely, his work being a mixture of histor-iography, philosophy and political theory.However, the origins of Ranciere’s work onpolitical theory is instructive. Ranciere hadbeen one of Louis Althusser’s students,

working on the former’s Reading Capital(Althusser et al. 1965). In the midst of theMay 1968 Paris uprisings, Ranciere brokewith his former teacher. Ranciere (2003)described the distance between Althusser’sstructural accounts of capitalist society tothe scenes on the streets as ‘almost laughable’.What Althusser’s accounts of capitalismmissed—totally—was the ways in whichpeople became political subjects. That is, theways in which politics gets formulated andenacted. This turning point inspired Ranciereto develop social and political theory in a waythat navigates a path between the particulari-ties of subjectification and the universallogics of politics and economics.

Ranciere (1999) reserves the term ‘politics’for a very particular application. Most appli-cations of the term ‘politics’ refer to any con-testation that takes place within or betweensocieties. This conflict can be about resourcesor rights, but it necessarily involves a con-testation about what is held in common:

‘Justice as the basis of community has not yetcome into play wherever the sole concern iswith preventing individuals who live togetherfrom doing each other reciprocal wrongs andwith reestablishing the balance of profits andlosses whenever they do so. It only beginswhen what is at issue is what citizens have incommon and when the main concern is withthe way the forms of exercising and ofcontrolling the exercising of this commoncapacity are divided up.’ (Ranciere 1999, 5)

When we start to be concerned with commonlots, we need a criterion with which to assessour allocations: ‘The political begins preciselywhen one stops balancing profits and lossesand worries instead about distributingcommon lots and evening out communalshares and entitlements to these shares’ (Ran-ciere 1999, 5). Ranciere notes that there existmany different criteria upon which we mightassess our allocations. Democracy, he insists,provides a very distinct criterion, based onthe absence of any natural titles to govern.Where other criteria for allocation are pre-mised on the notion that some people (be

658 CITY VOL. 19, NO. 5

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cla

rk U

nive

rsity

], [

Mar

k D

avid

son]

at 0

9:21

18

Febr

uary

201

6

they the wealthy, the learned, the male, thewhite, the elders, etc.) have a natural rightto exercise authority over others, democracyis scandalous because it presumes the equalityof all. Politics, for Ranciere (1999, 16), takesplace when that radical equality is enactedby those whose equality is denied in an exist-ing social order:

‘Politics occurs because, or when, the naturalorder of the shepherd kings, the warlords, orproperty owners is interrupted by a freedomthat crops up and makes real the ultimateequality on which any social order rests.’

Or, as he puts it elsewhere: ‘politics existswherever the count of parts and parties ofsociety is disturbed by the inscription of apart of those who have no part’ (Ranciere1999, 123). There are many ramifications ofthis political theory, so it is necessary topick out just two points that are closelyrelated to this discussion. The first point con-cerns the universal operation of politicswithin various social and temporal contexts,and the second point looks at the consequentrelationship between the universal and par-ticular dimensions of the lifeworld.

Ranciere’s writing on how politics relatesto the city can be a little disorientating. Atone moment, you are reading about disputesin the Greek polis, the next you are in thestreets of Paris in 1968. In his use of variousexamples, Ranciere is demonstrating asimple point: that politics is universal, butnecessarily emerges out of the particular. Itis not that any one type of issue (or indeedplace) is any more political than any other,nor that equality has a pre-given meaningoutside of specific contexts (and contests):

‘Nothing is political in itself for the politicalonly happens by means of a principle thatdoes not belong to it: equality. The status ofthis “principle” needs to be specified.Equality is not a given that politics thenpresses into service, an essence embodied inthe law or a goal politics sets itself the task ofattaining. It is a mere assumption that needs tobe discerned within the practicesimplementing it.’ (Ranciere 1999, 33)

Politics, then, is founded in the manifestationof an inequality and the enactment of equalitythrough a process of political subjectification.The potential for politics is therefore timelessand placeless, but the emergence of politics isalways contextual and situated. The relation-ship between particular/unequal treatmentand universal politics is critical for Ranciere.It means that politics does not occur withinthe abstract. It is that the concrete—what heoften refers to as the allocation of spaceswithin the police order—must be held in dia-logue with the abstract (i.e. equality/democ-racy). One can only identify these(universal) things within the operation of par-ticular practices. The necessity of dialecticalthought is here, again, demonstrated. No sur-prise then that Ranciere uses examples ofpolitics that range from the Plebeians toRosa Parks. In the absence of any concreteuniversality, we must therefore understandthe universal through the particular.

Again, this dialectical navigation can guideus in understanding the planetary urbaniz-ation condition. If planetary urbanizationrepresents the extension of urbanizationlogics (i.e. a particular capitalist accumulationprocess) across a host of ‘urban fabrics’,which for us include ‘cities’, then we are leftwith a task of understanding how the particu-larities of the urban fabric are shaped and/ordictated by the abstract/universal logics.

A cursory look across a host of politicalmoments that have occurred since 2007reveal that ‘the city’ is often central in howpeople understand their engagement withstructural processes, and how they articulatetheir complaints against it. The counter-movement against zombie neoliberalism(Peck 2010) has, we would argue, been com-prised of a host of predominantly city-basedstruggles that have, at times, been able tounite through an acknowledgement of theircommon causes and concerns (Davidsonand Iveson 2014b). If we omit these elementsof the political process from our criticalurban research, we are left only with theabstract universal. The categories withinwhich people form and order their lives are,

DAVIDSON AND IVESON: BEYOND CITY LIMITS 659

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cla

rk U

nive

rsity

], [

Mar

k D

avid

son]

at 0

9:21

18

Febr

uary

201

6

in large part, dispensed with. An ability toconnect our contingent and ever-changingsocial categories—what Louis Wirth (1938)might have called social heterogeneity—tothe universal structuring of global capitalismis greatly reduced, if not lost completely.

Furthermore, our ability to think about thecity as a formulator and stage for politics isremoved. We are left with a politics that is pre-ordained; politics is reduced to being anoutcome of the structural divisions createdby planetary urbanization. The subjectifica-tion process is pre-defined, and all thatremains is for people to realize their structuralinterests at the planetary scale. Such anapproach therefore forecloses an active andongoing engagement with the particularforms of democratic politics taking place incities, in which people are finding ways toenact their equality against the inequalities ofthe social order in which they find themselves.In contrast to this, we argue that maintainingthe concept of the city, in dialogue with theurban, is necessary for politics itself. The cityis a key domain in which subjectification (i.e.fighting against inequality through the enact-ment and inscription of equality into the exist-ing police order) becomes contestation. It alsoserves as the space whereby this contestationcan be staged, where claims are articulatedand the legitimacy of criteria for allocation istested (Davidson and Iveson 2014a).

Note that within this formulation of poli-tics, while we think that right now wecannot do without the idea of the city, wedo not seek to reintroduce a timeless, place-less or bounded concept of ‘the city’ as a pri-vileged space of the political. Indeed,Ranciere (1999, 10) warns us against anysuch idea that politics has a proper place:

‘What makes an action political is not itsobject or the place where it is carried out, butsolely its form, the form in whichconfirmation of equality is inscribed in thesetting up of a dispute, of a communityexisting solely through being divided.’

Rather, our point is to suggest that a criticalurban theory concerned with emancipation

ought to have the tools to help us understandwhen, where and how ‘the city’ does emergeas a site of the political, as it has done inrecent years. Cities are once again emergingas spaces where inequality is founded/recog-nized and where democratic equality isenacted. If urbanization is indeed becomingplanetary, a renewed and relational politicsof the city is a potential resource in thestruggles to come, not an impediment tosuch struggles. As the universal dimensionof planetary urbanization therefore becomesincreasingly dominant over peoples’ lives,perhaps paradoxically it becomes moreimportant that we prioritize our analysis ofthe particular: ‘The key moment of anytheoretical (and ethical, and political, and—as Badiou demonstrated—even aesthetic)struggle is the rise of universality out of theparticular life-world’ (Zizek 2007, n.p.).None of this forecloses a global anti-capitalistpolitics. Indeed, it should empower such apolitics, given the fact it enables particular/emplaced struggles to contest those universalstructures that define much of our lives. Foran emancipatory politics of planetary urban-ization to emerge, we argue, relies greatlyon ‘the city’ within a dialectic with ‘theurban’. To understand and intervene in thisdialectic is, in our view, the way for criticalurban theory to proceed.

We would also add that this approach tocities and the urban leaves space for ‘therural’ to continue to matter for spatial theoryand emancipatory politics in a similar mannerto—and indeed, in relation to—‘the city’ (seealso Catterall 2015). Even if we reject aconcept of ‘the city’ that is fixed andbounded, we are not required to also rejectany concept of a non-urban ‘outside’. Forexample, while we are no experts here, wecan see no reason to jettison a relationalconcept of ‘the rural’. We might even askwhether or not contemporary developmentssuch as the growth of global agri-businessthat Brenner and Schmid see as moments of‘extended urbanization’ might not also consti-tute moments of ‘extended ruralization’ at thesame time. Such a relational approach to the

660 CITY VOL. 19, NO. 5

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cla

rk U

nive

rsity

], [

Mar

k D

avid

son]

at 0

9:21

18

Febr

uary

201

6

rural would also allow for struggles for equalityemerging from emplaced struggles over thefuture of rural communities. For instance, thecontemporary ‘Lock the Gate’ movement inAustralia has involved an exciting alliance ofrural property-owners, rural communities andurban activists in refusing to allow explorationfor coal seam gas on agricultural land (Hutton2012). Certainly, this movement has high-lighted the ‘urban’ drivers of coal seam gasexploration, with fossil fuel companiesseeking to profit by supplying growing Austra-lian cities with cheap sources of energy.However, the contestation of this process hasinvolved an encounter between those who areexplicitly oriented towards the possiblefutures of ‘the city’ and ‘the country’. Asurban environmental activists travel to campout at farm gates, and as farmers and their com-munities reach out to urban-based politicalgroups and media, they have expressed andtransformed—rather than transcended—theirplace-based identities and aspirations.

Conclusion

For Brenner and Schmid (2015a, 159), thechanging constitution of the contemporaryurban condition demands that ‘vigilant analy-sis and revision of the very conceptual andmethodological frameworks being used toinvestigate the urban process’. The emergentdebate on planetary urbanization will becentral to the development of critical urbantheory and, hopefully, the contribution ofcritical urban theory to political change. Inthis regard, the recent manifesto set out byBrenner and Schmid (2015a) is a highly valu-able contribution. It has formalized andassertively extended a set of debates thathave been circulating with critical urbanstudies for some time. Put simply, it is nowdifficult to ignore a debate about planetaryurbanization. Indeed, in our own work, weare finding it to be a productive heuristic inmany different applications.

Nevertheless, in this contribution we havedrawn upon our recent work on the

prospective direction of critical urbantheory to suggest some limitations to the pla-netary urbanization thesis. A central concernmotivating our intervention has been ourbelief that ‘the city’ remains an importantanalytical and political category. As such,we resist calls for the analytic to be dispensedwith and/or sidelined. We think that ‘the city’both exists and requires consistent interrog-ation with regards to its relationship to theurbanization process and the political. Therelationship between ‘the city’ and ‘theurban’ has, we would argue, long beenthought of—both implicitly and explicitly—as a dialectical one. At its most extremelengths, we think the planetary urbanizationthesis can suggest that such a dialecticalrelation no longer exists. This interpretationis both theoretically and politically proble-matic. The task at hand is therefore to under-stand just how the city operates within anurbanization process that has becomerequired within a systemically dysfunctionalform of capitalism.

Maintaining a concern for the city/urbandialectic is also crucial in terms of formulat-ing a truly critical urban theory. For toolong, much critical urban theory has onlyserved to reconfirm its own critique. Else-where we have argued that critical urbantheory must be more concerned with the for-mulation and presentation of political claims;what we refer to as a ‘method of equality’(Davidson and Iveson 2014a). Within thisproject, influenced by the work of JacquesRanciere (1999), we have found that ‘thecity’ is often formative for many of today’spolitical struggles. ‘The city’ remains a site/component of political subjectification and astage within which political claims are articu-lated. As we hope to have made clear, ourconceptual and political defense of ‘the city’as an anchor for critical urban studies isabsolutely not a call for a return ofbounded, universal concepts of ‘the city’that have rightly been the target of critique.Rather, it is a call for us to put our concernsabout the injustices of capitalist urbanizationprocesses into dialogue with the political

DAVIDSON AND IVESON: BEYOND CITY LIMITS 661

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cla

rk U

nive

rsity

], [

Mar

k D

avid

son]

at 0

9:21

18

Febr

uary

201

6

practices that are emerging from (while cer-tainly not contained within) subordinatedpeoples in a diverse range of cities (see alsoSheppard, Leitner, and Mariganti 2013,897–899). Put simply, for many millions ofpeople across the planet, the particularitiesof city life form the context from which pla-netary urbanization is experienced, under-stood and potentially transformed.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Neil Brenner for hissubstantive and clarifying feedback on anearlier draft of this paper. Although we maystill have significant differences in our theor-etical interpretations, Neil’s supportiveengagement with the paper helped to pre-cisely identify our points of disagreement.Thanks are also due to Elvin Wyly for hissubstantial feedback on an early draft of thepaper. All the usual disclaimers apply.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by theauthors.

Notes

1 We should also note as we begin that for the mostpart, we are engaging here with the piece Brennerand Schmid have recently published in City, ratherthan engaging with the wider corpus of the work thatthey have produced both together and separately. Ifthis has resulted in any particular omissions ormisunderstandings of their position, then we can onlyapologize, and offer the hope that the ongoingdialogue and debate with ourselves and others willresult in clarifications.

2 For a few years, as a consequence of a dispute withhis former record label, musical artist Prince droppedhis name, and insisted on using a symbol in its place.He became ‘the artist formerly known as Prince’ inofficial communications. But we all kinda knew hewas still Prince . . .

3 The dialectical relationship between the city andurbanization also seems to us to emerge fromLefebvre’s ([1970] 2003) conceptualization of theparticular (i.e. city) and universal (i.e. urbanization).His seminal work on an urbanized planet sought to

explain how a certain logic of capitalist developmenthad become imbued across earthly life-makingprocesses. Urbanization, for Lefebvre, was becominga predominant feature of social life; something distinctfrom prior processes of industrialization. He certainlyclaimed that urbanization and its associated fabricsexceeded the city per se. But note theway in which thisis articulated:

‘The urban fabric grows, extends its borders,corrodes the residue of agrarian life. Thisexpression, “urban fabric”, does not narrowlydefine the built world of cities but allmanifestations of the dominance of the cityover the country. In this sense, a vacationhome, a highway, a supermarket in thecountryside are all part of the urban fabric.’(Lefebvre [1970] 2003, 4)

Here it seems to us that Lefebvre’s conception of anextended ‘urban fabric’ that takes a diversity of formsstill delineates between the city—as something thatextends influence amongst hinterlands—andurbanization as a process. In this passage, thesupermarket remains in the country, but thesupermarket brings with it something of the city. If weentirely abandon the distinction between city andcountry (or of any similar spatial designations), thenour ability to develop Lefebvre’s theoretical andpolitical project becomes significantly limited. To putthis another way, Lefebvre certainly distinguishesbetween the city and this planetary urbanizationprocess, but does not argue that urbanization hastherefore transcended the city. Instead, there is a newrelation to be explained and critiqued. A focus on‘the city’ as a bounded, stable object will not do—hisconcept of an ‘urban fabric’ is:

‘preferable to the word “city”, which appearsto designate a clearly defined, definitiveobject, a scientific object and the immediategoal of action, whereas the theoreticalapproach requires a critique of this “object”and a more complex notion of the virtual orpossible object’. (Lefebvre [1970] 2003, 4)

Here then, notions of ‘the city’ as a ‘clearly defined,definitive object’ are to be critiqued, but to us thisimplies a critical orientation towards ‘the city’ ratherthan dispensing with it.

References

Althusser, L., E. Balibar, R. Establet, P. Macherey, and J.Ranciere. 1965. Lire le Capital. Paris: Maspero.

Amin, A., and N. Thrift. 2002. Cities: Reimagining theUrban. Cambridge: Polity Press.

662 CITY VOL. 19, NO. 5

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cla

rk U

nive

rsity

], [

Mar

k D

avid

son]

at 0

9:21

18

Febr

uary

201

6

Angelo, H., and D. Wachsmuth. 2015. “UrbanizingUrban Political Ecology: A Critique of MethodologicalCityism.” International Journal of Urban and RegionalResearch 39 (1): 16–27.

Brenner, N. 2009. “What is Critical Urban Theory?” City13 (2): 198–207.

Brenner, N. 2014. Implosions/Explosions: Towards aStudy of Planetary Urbanization. Berlin: Jovis.

Brenner, N., and C. Schmid. 2014. “The ‘Urban Age’ inQuestion.” International Journal of Urban andRegional Research 38 (3): 731–755.

Brenner, N., and C. Schmid. 2015a. “Towards a NewEpistemology of the Urban?” City 19 (2/3): 151–182.

Brenner, N., and C. Schmid. 2015b. “Combat, Caricature& Critique in the Study of Planetary Urbanization”.http://www.soziologie.arch.ethz.ch/_DATA/90/BrennerSchmid2.pdf

Catterall, B. 2015. “Editorial: ‘You’re surrounded . . . ’”City 19 (2/3): 145–150.

Davidson, M., and K. Iveson. 2014a. “Recovering thePolitics of the City: From the ‘Post-political City’ to a‘Method of Equality’ for Critical Urban Geography.”Progress in Human Geography, online first version.doi: 10.1177/0309132514535284.

Davidson, M., and K. Iveson. 2014b. “Occupations,Mediations, Subjectifications: Fabricating Politics.”Space and Polity 18 (2): 137–152.

Dikec, M. 2007.Badlands of the Republic. Oxford: Blackwell.Dikec, M. 2013. “Beginners and Equals: Political Subjec-

tivity in Arendt and Ranciere.” Transactions of theInstitute of British Geographers 38 (1): 78–90.

Farıas, I., and T. Bender. 2012. Urban Assemblages: HowActor Network Theory Changes Urban Studies.New York: Routledge.

Glaeser, E. 2011. Triumph of the City : How Our GreatestInvention Makes us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Heal-thier, and Happier. New York: Penguin Press.

Gleeson, B. 2012. “Critical Commentary. The Urban Age:ParadoxandProspect.”UrbanStudies49 (5):931–943.

Harvey, D. 1973. Social Justice and the City. London:Edward Arnold.

Harvey,D.1996. “Cities orUrbanization?”City1/2:38–61.Harvey, D. 2014. “The Crisis of Planetary Urbanization.”

http://post.at.moma.org/content_items/520-the-crisis-of-planetary-urbanization

Heynen, N., M. Kaika, and E. Swyngedouw, eds. 2006. Inthe Nature of Cities: Urban Political Ecology and thePolitics of Urban Metabolism. New York: Routledge.

Holston, J., ed. 1999. Cities and Citizenship. Durham, NC:Duke University Press.

Hutton, D. 2012. “Lessons from the Lock the Gate Move-ment.” Social Alternatives 31 (1): 15–19.

Isin, E., ed. 2001. Democracy, Citizenship and the GlobalCity. New York: Routledge.

Iveson, K. 2014. “Building a City for ‘The People’: ThePolitics of Alliance-Building in the Sydney Green BanMovement.” Antipode: A Radical Journal ofGeography 46 (4): 992–1013.

Lefebvre, H. 1991. The Production of Space. Oxford:Blackwell.

Lefebvre, H. (1970) 2003. The Urban Revolution. Min-neapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Mason. 2013. Why it is Still Kicking off Everywhere.London: Verso.

Massey, D. 2007. World City. Cambridge: Polity Press.Massey, D., J. Allen, and S. Pile, eds. 1999. City Worlds.

London: Routledge.McFarlane, C. 2011. “Assemblage and Critical Urban-

ism.” City 15 (2): 204–224.Merrifield, A. 2002. Dialectical Urbanism: Social

Struggles in the Capitalist City. New York: MonthlyReview Press.

Merrifield, A. 2014. The New Urban Question. New York:Pluto Press.

Mumford, L. 1966. The City in History: Its Origins, itsTransformations, and its Prospects. Harmondsworth:Penguin.

Peck, J. 2010. “Zombie Neoliberalism and theAmbidextrous State.” Theoretical Criminology 14 (1):104–110.

Ranciere, J. 1999. Disagreement: Politics and PhilosophyRose J trans. Minneapolis, MN: University of MinnesotaPress.

Ranciere, J. 2003. “Politics and Aesthetics an interview.”Angelaki: Journal of the Theoretical Humanities 8:191–211.

Robinson, J. 2006. Ordinary Cities: Between Modernityand Development. London: Routledge.

Roy, A., and A. Ong, eds. 2011. Worlding Cities: AsianExperiments in the Art of Being Global. Oxford:Wiley-Blackwell.

Sandercock, L. 2002. Cosmopolis II: Mongrel Cities in the21st century. London: Continuum.

Sassen, S. 2001. The Global City: New York, London,Tokyo. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Satterthwaite, D. 2003. “The Millennium DevelopmentGoals and Urban Poverty Reduction: Great Expec-tations and Nonsense Statistics.” Environment andUrbanization 15 (2): 179–190.

Saunders, D. 2010. Arrival City: The Final Migration andOur Next World. Crows Nest: Allen and Unwin.

Scott, A. J., and M. Storper. 2014. “The Nature of Cities:The Scope and Limits of Urban Theory.” InternationalJournal of Urban and Regional Research 39 (1):1–15.

Sheppard, E., H. Leitner, and A. Mariganti. 2013. “Pro-vincializing Global Urbanism: A Manifesto.” UrbanGeography 34 (7): 893–900.

Story, L., and S. Saul. 2015. “Towers of Secrecy: Stream ofForeign Wealth Flows to Elite New York Real Estate.”New York Times, 7 February. Accessed June 30,2015. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/08/nyregion/stream-of-foreign-wealth-flows-to-time-warner-condos.html?_r=0

Swyngedouw, E. 2009. “The Antinomies of the Postpoliti-cal City: In Search of a Democratic Politics of

DAVIDSON AND IVESON: BEYOND CITY LIMITS 663

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cla

rk U

nive

rsity

], [

Mar

k D

avid

son]

at 0

9:21

18

Febr

uary

201

6

Environmental Production.” International Journal ofUrban and Regional Research 33 (3): 601–620.

Swyngedouw, E. 2010. “Apocalypse Forever? Post-politi-cal Populism and the Spectre of Climate Change.”Theory, Culture & Society 27 (2–3): 213–232.

Walker, R. 2015. “Building a Better Theory of theUrban: A Response to ‘Towards a New Epistemologyof the Urban’?” City 19 (2–3): 183–191.

Wirth, L. 1938. “Urbanism as a Way of Life.” AmericanJournal of Sociology 44 (1): 1–24.

Zizek, S. 2007. “Tolerance as an Ideological Category.”Critical Inquiry (Autumn). http://www.lacan.com/zizek-inquiry.html.

Mark Davidson is Assistant Professor ofGeography in the Graduate School ofGeography at Clark University. Email:[email protected]

Kurt Iveson is Associate Professor of UrbanGeography in the School of Geosciences atthe University of Sydney. Email: [email protected]

664 CITY VOL. 19, NO. 5

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cla

rk U

nive

rsity

], [

Mar

k D

avid

son]

at 0

9:21

18

Febr

uary

201

6