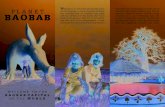

Baobab issue 58 july 2010

-

Upload

susan-mwangi -

Category

Documents

-

view

2.831 -

download

1

description

Transcript of Baobab issue 58 july 2010

livestock

A magazine on drylands development and sustainable agriculture / ISSUE 58, JULY 2010

Enhancing small-scale

production

E D I T O R I A L

Dear Reader, Welcome to the new look Baobab! The new magazine is a merger of the old Baobab and Kilimo Endelevu Africa (KEA). It will now be longer, increasing in extent from 24 to 36 pages therefore enabling us to share more information that responds to the growing needs of our readers in East Africa.

The merged Baobab will also feature more articles from the ‘AgriCultures’ network that produces Farming Matters, an international quarterly magazine

that focuses on small-scale sustainable agriculture. AgriCultures is a global network of organisations coordinated by the Centre for learning on sustainable agriculture (ileia) and supports the production of regional editions in Latin America (Peru and Brazil), West Africa (Senegal) and Asia (India, China and Indonesia) with new Baobab now being the East African edition (Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania).

Farming Matters, which was until this year known as Leisa magazine, was started 25 years ago by a group of enthusiastic people who believed that agricultural

practices recommended by scientists in universities and research institutions were not always responsive to field level realities. They were convinced that there was relevant and valuable knowledge among farmers and field workers which needed to be captured and shared more widely. Baobab has since inception served a similar function with a focus on East Africa. It will continue to serve primarily community development workers or infomediaries who constitute ALIN’s membership in the region.

We also believe it will appeal to anyone interested in issues affecting communities living in arid lands of Eastern Africa and therefore provide an extra channel for sharing best practices in agriculture and sustainable utilization of the environment.

The merger process involved close consultation with ileia. In this inaugural issue, we carry an interview with Edith van Walsum, the Director of ileia, who gives more details about the process.

The theme for this issue is “Small-scale livestock production”. We welcome your feedback and ideas about making Baobab a more effective forum for sharing information for sustainable small-scale agriculture in our region.

James NguoRegional Director

Welcome to the new look

Baobab

ISSN: 0966-9035

Baobab is published four times a year to create a forum for ALIN members to network, share their experiences and learn from experiences of other people working in similar areas.

Editorial boardJames NguoAnthony MugoNoah LusakaEsther Lung’ahiSusan Mwangi – Chief Editor

Consulting EditorWairimu Ngugi

IllustrationsJoe Barasa

Consulting DesignerLevi Wanyoike

Important noticesCopyright: Articles, photos and illustrations from Baobab may be adapted for use in materials that are development oriented, provided the materials are distributed free of charge and ALIN and the author(s) are credited. Copies of the samples should be sent to ALIN.

Disclaimer: Opinions and views expressed in the letters and articles do not necessarily reflect the views of the editors or ALIN. Technical information supplied should be cross- checked as thoroughly as possible as ALIN cannot accept responsibility should any problems occur.

Regional editions1. Farming matters global edition by ileia

2. LEISA REVISTA de Agroecologia, Latin America edition by Asociacion ETC andes.

3. LEISA India, by AME foundation

4. SALAM majalah pertanian Berkelanjutan by VECO Indonesia

5. AGRIDAPE, French West African edition by IED afrique

6. Agriculture, experiences em Agroecologia, the Brazilian edition by AS-PTA

7. Chinese edition by CBIK

Talk to usThe Baobab magazine Arid Lands Information Network, ALINPO Box 10098, 00100 Nairobi, KenyaAAYMCA Building, Ground floorAlong State House Crescent,Off State House AvenueTel. +254 20 2731557, Telefax. +254 20 2737813Cell. +254 722 561006, Email: [email protected] visit us at www.alin.net

About ALINArid Lands Information Network (ALIN) is an NGO that facilitates information and knowledge exchange to and between extension workers or infomediaries and arid lands communities in the East Africa region. The information exchange activities focus on small-scale sustainable agriculture, climate change adaptation, natural resources management and other livelihood issues.

ContentsLivestock a smart solution for food and farming 4

Multiple benefits of goat keeping 8

Fighting East Coast fever - lessons from Maasailand 11

Livestock breeding 13

Pastoralism, shifts in policy making 15

Stork Story 18

Small-scale livestock production-Malawi 20

Capacity building for PLWHA-Uganda 22

Small-scale pig farming - Uganda 26

Guest Column 30

Camel milk 32

Baobab writing guidelines & Call for articles 33

Resources 34

From our Readers 35

4

8

15

26

30

BAOBAB ISSUE 58, JULY 20104

T H E M E O V E R V I E W

Livestock plays an important role in the livelihoods of many farmers and herders in the developing world, as it contributes to

the basics of food, income, and security, as well as other social and cultural functions. Actually, the world’s poorest people – nearly one billion – depend on pigs, yaks (a wild domesticated ox), cattle, sheep, lamas, goats, chickens, camels, buffalos and other domestic animals. For undernourished people, selling one egg may imply being able to buy some rice and thus, instead of having one meal per day, a second one becomes reality. This is a typical survival strategy: selling high-quality foods to buy low-cost starchy food. In other parts of the world, we see an over-consumption of red meat and other animal-based food, which damages the health of many people: it is a shocking dichotomy.

Greenhouse gases produced by animalsAccording to the FAO study, Livestock’s long shadow: Environmental issues and options, published in 2006, livestock contributes to 18 percent of the total global greenhouse gas emissions generated by human activity. Most of these emissions come from countries using industrial farming practices, in the form of methane produced by the belching and flatulence of animals, carbon dioxide by felling and burning trees for ranching, and nitrous oxide by spreading

manure and slurry over the land. It is therefore a problem predominantly caused by western consumption patterns, as has been discussed and studied by many researchers and authors (for example, Jonathan Safran Foer in Eating Animals). For some people, it is a reason to promote a vegetarian lifestyle, as a protest against animal exploitation.

There are, however, great differences in livestock production systems in various regions of the world. These systems emit very different amounts and types of greenhouse gases, and serve different purposes. Considering that all of Africa’s ruminants together account for three percent of the global methane emissions from livestock, their

a smart solution for food and farmingAnimals are a part of farming systems everywhere. In this issue, Baobab focuses on

how small-scale farmers manage their animals, how they link animal husbandry with other activities and what their livestock means to them. An integrated perspective on the role of farm animals is crucial in overcoming simplistic

assumptions on the opportunities and threats that livestock presents to family farmers. By Lucy Maarse

Livestock

Mrs Jerida Matasi a small-scale farmer milking her cow in Lugulu, Kenya

BAOBAB ISSUE 58, JULY 2010 5

contribution is minor. But as Carlos Seré, director of the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), rightly points out: ruminants maintained on poor quality feeds make an inefficient conversion of feed to milk and meat, and more environmentally damaging. Skinny ruminants on poor diets, while not competing with people for grain, produce much more methane per unit of livestock product than well-fed cattle, sheep and goats.

Yet many African livestock systems seem to be the best way to deal with climate change because these systems can be carbon-negative. According to Mario Herrera and Shirley Tarawali from ILRI, a typical 250 kilogram African cow produces approximately 800 kilogram CO2 equivalents per year, whilst carbon sequestration rates (the amount of carbon taken up in the soil) can be about 1400 kilograms of carbon per hectare per year under modest stocking rates, making a positive balance. The same goes for stall-feeding dairy systems, which emit less CO2 due to higher quality diets and better recycling of products within the system.

Livestock revolution revisitedThe notion of a “Livestock Revolution” was introduced in an influential International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) publication in 1999. It initially simply stood for the unprecedented growth in demand for food of animal origin in developing countries, because of population growth, urbanization and increasing income (and subsequent changes in diets and life style). The idea that the Livestock Revolution would be driven by demand, contrary to the Green Revolution which was supply driven, strongly influenced the thinking in the sector.

The growth in demand could imply enormous opportunities for the poor, who could catch a substantial share of the growing livestock market. But just 10 years later, Pica-Ciamarra and Otte show in The livestock revolution: rhetoric and reality, that this growth has been especially huge in China, India and Brazil in the poultry, pork and dairy sectors. In sub-Saharan Africa and developed regions, the growth has been decreasing or stagnant. The geographical impact is patchy even within the nations and the impact is largest on poor urban consumers. The paper also observes that an increasing polarisation has occurred in the livestock sector.

Local developmentsThe World Bank has embraced the notion of a livestock revolution from the beginning, sensing opportunities for poor small-scale farmers in developing countries. Jimmy Smith from the Agriculture and Rural Development department of the World Bank admits that growth in the demand for animal products has not been uniform: “Income growth has mostly happened in China. In South East Asia the demand for milk, poultry meat and eggs has increased enormously.” For Smith, this does not mean that the livestock revolution did not occur: “Despite regional

differences, changes have been so large that it has influenced global trade, livestock and climate. As smallholders are often not connected to markets, they have not been able to benefit as we would have expected.” According to Smith, policymakers need to be more specific on local situations: “It’s mostly the private organisations that have benefited from the livestock revolution.

Public spending has been very low. Veterinary services have deteriorated. And there have been no investments in links to markets.” There are

“It’s mostly the private organisations that have

benefited from the livestock revolution. Public

spending has been very low. Veterinary services have deteriorated. And there

have been no investments in links to markets.”

BAOBAB ISSUE 58, JULY 20106

more examples indicating that the livestock sector is influenced by other factors, such as food price policies, availability of animal feed and investment facilities for commercial farming. The idea of a livestock sector that grows as a result of increased demand for meat is therefore misleading. It prevents governments from intervening and identifying the real potentials that could stimulate a growth in the livestock sector that would be beneficial to poverty reduction and rural development at large.

Mixed farmingIn Eastern Africa, one third of the rural population lives in areas where livestock predominate over crops as a source of income. Nearly 40 percent of all livestock are kept in mixed farming areas, where they contribute to rural livelihoods in diverse ways. Various classifications are used to define livestock production systems. From a family farming perspective, livelihood criteria known as “the relative dependency on livestock at the household level” including the customary use of the terms “pastoral”, “agro-pastoral”, and “mixed farming”, place the livestock into perspective with all the activities and resources through which households fulfil their needs. An agro-pastoral system would be one in which livestock account for between 50 and 80 percent of the total income, whereas a pastoral system would have livestock accounting for over 80 percent.

Caution is needed in making generalised statements about the links between livestock, consumption of meat, greenhouse gas emissions, climate change, food safety, poverty and animal welfare issues. The context, functions of livestock and trade-offs of animal husbandry are very different all over the world. The crux of the matter is to reach a situation in which family farming and herding in the developing countries meet

future demands for animal products without environmental damage. Strengthening and/or developing ecological, cultural and socially-sound livestock systems is possible, but it starts with understanding the different functions of livestock in rural livelihoods.

Livestock means more than meat and milkFarmers keep animals for direct consumption of food and non-food products such as milk, meat, wool, hair and eggs, but also manure for fuel and urine for medicine (output function). Some of these products provide input for other activities: manure, urine and grazing fallow land are beneficial for crop production; stubble fields

help pastoralists feed their animals; animals give drought power for transport and their hair, hoofs and manure help to disperse seeds and improve seed germination; their grazing prevents bushfires and controls shrub growth, and stimulates grass tillering and breaking-up

hard soil crusts (input function). But animals also permit farmers to raise money in times of need (asset function). This often represents the priority function of livestock among poor farmers, and is the reason that animals are not necessarily sold when the market price is attractive but when there is a need for cash. Livestock are also part of the household. They are indicators of social status, festivals and fairs are based on livestock (bullock cart racing, cock fighting, cow beauty contests) and many songs have been written about livestock (socio-cultural function).

Van der Ploeg (2009) brings in the dimension of capital when analysing farming systems in his book New Peasantries. There is the conversion of living nature (ecological capital) into food, drinks and a broad range of raw products. But controlling the complex organisation and development of farming, needs communities to network, cooperate, self-regulate, solve conflicts,

Van der Ploeg (2009) brings in the dimension of capital

when analysing farming systems in his book New

Peasantries

T H E M E O V E R V I E W

BAOBAB ISSUE 58, JULY 2010 7

and engage in learning processes (social capital). Finally, farming and herding stand for a certain culture and way of life (cultural capital), which are even more clearly articulated in these modern times, with anonymous global markets. Farming culture stands for origin, quality, authenticity and freshness of products, and of associated ways of producing, processing and marketing (fairness and sustainability).

The analyses of Rangnekhar (2006) and Van der Ploeg (2009) can be combined in the diagram below:

Livestock Production Systems: their functions and relationships to capitalThe World Bank has already tried to adopt a more inclusive approach to livestock. Smith points out that livestock is mostly used for input into crops: “Some reports say that up to 50 percent of nitrogen use for crops comes from manure, which means that livestock is incredibly important. Livestock has many uses and functions, which have not received enough attention. Public investments are needed, in order to sustainably develop the livestock sector and escape poverty.”

Climate smart rural development A recent study by Delgado (2008) on the scaling-up of the production of some specific livestock products among small-scale producers in Brazil,

India, the Philippines and Thailand, has focused on the impact of increasing the average farm size and annual livestock sales. There are some interesting conclusions regarding family farming that can be noted. Independent small farms in India and the Philippines typically have higher profits per unit than do independent large farms. Small farms with pigs and poultry also have a lower negative impact on the environment than large farms. Hence, environmental concerns are compatible with promoting small-scale livestock pr oduction. Climate-smart farming is the future, as Camilla Toulmin, director of the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) stated at the ileia conference on the Future of Family Farming in The Hague in December 2009.

About the author

Lucy Maarse is an independent livestock advisor, specialised in tropical animal production and extension. She currently works in the Netherlands.Email: [email protected]

References

Delgado, C. (2008), Determinants and implications of the growing scale of livestock farms in four fast-growing developing countries, IFPRI Washington D.C. Research report 157.

Delgado C., Rosegrant M., Steinfeld H., Ehui S., Courboi, C. (1999), Livestock to 2020 – The Next Food Revolution. Food, Agriculture and the Environment. IFPRI, Washington D.C. Discussion Paper 28.

Van der Ploeg, J.D. (2009), The New Peasantries, struggles for autonomy and sustainability in an era of empire and globalization, Earthscan, London, UK.

Pica-Ciamarra, U. and Otte, J. (2009), The livestock revolution: rhetoric and reality. FAO Rome.

Rangnekar D. (2006) Livestock in the livelihoods of the underprivileged communities in India: A review. ILRI, Nairobi, Kenya.

Steinfeld, H., Gerber, P., Wassenaar, T., Castel, V., Rosales, M., De Haan, C. (2006), Livestock’s Long Shadow – environmental issues and options. FAO Rome.

Sere, C. (2009). ‘It’s time for climate negotiators to put meat on the bones of the next climate agreement’. www.ilri.org/ilrinews/index.php/archives/1006/comment-page-1#comment-50.

Livestock Production Systems: their functions and relationships to capital

BAOBAB ISSUE 58, JULY 20108

The goat is one of the most adaptable and geographically spread out livestock species in the world, with an estimated population of 700 million. With a habitat ranging from the mountains of Siberia to the deserts and the tropics of Africa, goats provide reliable access to meat, milk, skin, fibre, high quality manure and other goat products. To boost goat breeding in Kenya where many rural communities rear them for food and income, Farm Africa, a Non-governmental Organisation, has initiated pilot milk goat projects in Mwingi, Kitui and Meru districts in the Eastern Province of Kenya.

Benefits of Goat KeepingAccording to the Mwingi District Farm Africa Manager, Mr Jacob Mutemi, many people keep goats for meat, skin and other benefits such as manure but ignore the milk, unaware of its high nutritional and medicinal value. He explains that in comparison to cow milk, goat milk has higher butter fat content and smaller fat globules that are beneficial to sick people. Research findings indicate that goat milk has the capacity to slow down the adverse effects of the life threatening HIV virus, thus prolonging life, notes Mr Mutemi. His views are echoed by the Mwingi District Range Management Officer, Mr John Njagi, who says: “Goat milk is exceptionally good for HIV positive people and those with full blown AIDS as it has been scientifically proven that it boosts the immunity of the sick.” He explains that his department is encouraging everyone including those who are HIV positive to consume goat milk because it enriches the T-cells in the blood. Infectious viruses normally attack T-cells, weakening the body’s defence mechanism.

Ancient cave paintings depicting people hunting goats indicate that the animal has historically played an important role in human food culture. Goats have traditionally contributed to ceremonial and cultural ceremonies during functions such as marriage and dowry negotiations, explains Mr Mutemi. He adds that goat milk and cheese were historically revered in ancient Egypt, with some pharaohs placing goatrelated foods among the valuable treasures in their burial chambers.

Mr Mutemi says that goat milk is nutritious and particularly good for young children and the sick. It is a source of calcium and the amino acid tryptophan, protein, phosphorus, riboflavin (vitamin B2) and potassium and bears a close resemblance to human milk due to its constitution. Research has shown that goat milk is a good alternative to breast milk for children whose lactating mothers become sick or die, while

Koki with her dairy goat . Photo: Musembi Nzengu

P R O J E C T F O C U S

Multiple benefits of Goat realised in MwingiBy Musembi Nzengu

keeping

BAOBAB ISSUE 58, JULY 2010 9

goat meat is soft and tender, says Mr Mutemi. He however notes that although goat rearing had evolved for over 10,000 years, there is need for a paradigm shift towards embracing milk goat rearing as opposed to rearing the animal solely for meat, skin and fibre. The table below from Farmer Dairy Goat Production Handbook provides a comparison of nutritional value between goat, cow and human milk.

Ngaani Case Study Ms Koki Safari is a mother of three and one of the leading goat farmers in Nuu Division of Mwingi District. After defying all odds she recently made history by selling a crossbreed goat at Kenya shillings 15,000 (USD 190) which is an equivalent of 10 times the price of a local goat in Nuu market. Narrated Ms Safari: “I joined Ngaani Dairy Goat Self-Help Group in 2004. The chief had called a baraza (a public meeting) and the poorest people in our location were identified and requested to form a self-help group. We were told that an organisation called Farm Africa wished to assist the poorest within the location. To benefit from the Project, we formed the Ngaani Group and registered it with Ministry of Culture and Social Services.” She was given two local goats for crossbreeding with an exotic male Toggenburg breed shared with other group members. Since

receiving two local goats in September 2004 Ms Safari now owns eight crossbred goats. She explains that since selling her goat for 15,000 (USD 190) Kenya shillings everyone in her village wants the goats. “The community members have realised these goats grow faster and produce more milk than the local goats. My husband and children are very happy with the project. I have been hosting many people who come to see the

goats. I have benefited from use of manure and the milk we get from the goats,” she explains with a sense of pride. She adds that her family’s social standing has risen as they are held highly and considered a good example of those who have succeeded in rearing the dairy goats. “My children are now very happy! They know that they cannot drop out of school due to lack of school fees.”

Ngooni Village Case Study Ms Telesia Ndeng’e is a 38-year-old widowed mother of three who hails from Ngooni

Village in Nzaatani location of Mwingi Central Division. She says the introduction of goat rearing in Ngooni by Farm Africa was a godsend that has emancipated her from the yoke of poverty. After only five years of marriage, Ms Ndenge’s husband, Mr Ndeng’e Muthui died in 2001, leaving her to fend for three young children, Muthui who is now 13 and a Kenya Certificate of Primary Education Candidate, Faith who is 10 and in standard 5 and Nzasu who is in standard 3.

Due to poverty, Ms Ndeng’e’s family suffered hunger among other problems, while crop production on their farm was impossible since she had to keep seeking manual jobs. The family was forced to sleep out in the cold when their mud walled and grass thatched house caved in. After their house collapsed, members of the Ngooni Africa Inland Church donated seven iron sheets, which the family placed over the mud walls of

Content Goat Cow Human

Protein 3.0 * 3.0 1.1

Fat 3.8 3.6 4.0

Calories/100ml 70 * 69 68

Vitamin A (iu/100ml) 39 * 21 32

Vitamin B (ug/100ml) 68 * 45 17

Riboflavin (ug/100ml) 210 * 159 26

Vitamin C (mg ascorbic acid/100ml) 2 2 3

Vitamin D (iu/gram fat) 0.7 * 0.7 0.3

Calcium 0.19 * 0.18 0.04

Iron 0.07 * 0.06 0.2

Phosphorus 0.27 * 0.23 0.06

Cholesterol (mg/100ml) *Low is good 15 20

Source: Kaberia, B.K, P. Mutia, and C. Ahuya - Farmers Dairy Goat Production Handbook. * Shows the best nutrition

their old house. Ms Ndeng’e reminiscences that in 2001 soon after her husband died [prior to introduction of free primary education in Kenya] her eldest son was out of school for months because she was unable to raise the 600 Kenya shillings (USD 7.5) required for school fees.

After being identified as among the poorest of

the poor, Ms Ndeng’e qualified for assistance through the Farm Africa goat rearing project and became one of the 25 members of the Utethyo Wa Ngya (Hope of the Poor) community group in Ngooni village. She was given four Gala milk goats to be mounted by an exotic Toggenburg he goat donated to the group to upgrade the local breed. She and other members of the milk goat project also received two-week training course as Community Animal Health Assistants and were each given a bicycle and a treatment kit.

“Soon after the training, I started crisscrossing the village on my bicycle attending to sick goats and advising fellow farmers on how to manage common diseases,” says Ms Ndeng’e. She soon started making some money out of the paravet services. As a priority she built a permanent two-roomed brick walled and iron sheet roofed house to ensure that “my family could for once sleep in comfort”. She was also able to ensure food and clothing was readily availed to her family members. Her fame as a para-vet spread and soon people who were not members of her group sought her help, which increased her income. In the meantime the three goats donated to her

by Farm Africa multiplied ten fold and by mid-February 2010 she was the proud owner of 30 goats.

Each of Ms Ndenge’s goats produces at least one pint (0.6 litres) of milk per day and the income realised from the sale of milk helps to supplement her earnings from community animal husbandry services. She has saved enough money to take her eldest son to secondary school next year and plans to sell four mature cross-bred goats. As a result of the goat project she is able to hire farm hands while the use of goat manure has helped to improved her farm yields and she expects to harvest 20 bags of maize at the end of the season.

The goat project has raised Ms. Ndenge’s profile and she is now recognised by the local community as an opinion leader. “It is true my profile has risen steadily and I now sit in the local locational development committee meetings all the way to the District Development Committee. I am also often called upon by various NGOs to co-facilitate workshops on capacity building for women and community based groups,” she says, explaining that this earns her some additional income.

About the Author

Musembi Nzengu is a writer based in Mwingi. He corresponds for various newspapers in Kenya. He can be on reached on 0724 560832 or [email protected]

Reference

Kaberia, B.K, P. Mutia and C. Ahuya “Farmer Dairy Goat Production Handbook.” Meru and Tharaka Nithi Dairy Goat and Animal Healthcare Project (1996 - 2003): 1

A dairy goat with full udder. Photo: Farm Africa

P R O J E C T F O C U S

BAOBAB ISSUE 58, JULY 201010

Every year, over one million cattle in East and Southern Africa die from East Coast Fever - about one cow every thirty seconds. In East Africa the loss amounts to about 190 million US dollars each year. East Coast Fever (ECF) (Theileriosis) is a cattle disease caused by the protozoan parasite Theileria parva. Though similar to Malaria, a tick called the Brown Ear Tick transmits it. The disease mainly occurs in Eastern and Southern Africa and is the number one killer of young cattle in the region.

SymptomsIn the event of infection, the parotid lymph nodes below the ear become enlarged 1 - 2 weeks after infection. A few days later, fever develops along with the enlargement of superficial lymph nodes in front of the shoulder and stifle. Other signs may include: difficulty in breathing, a soft cough due to accumulation of fluid in the lungs, blood-stained diarrhea, muscle wasting and white discoloration of the eyes and gums. The animal may appear disturbed resulting in the so called “turning sickness” and paralysis.

Ways of controlling East Coast FeverTreatment for a sick animal is expensive and costs between US dollars 50 to 60. The survival rate is also minimal. Another loss is the reduction in milk production. Regular dipping of cattle should be maintained. However, this may be difficult to attain in open herds without proper organization. Treatment with antibiotics such as long acting Oxytetracycline can occasionally cure the disease.

Tanzanian pastoralists pdopt vaccination to control East Coast FeverWhen asked about the success of vaccination against ECF in northern Tanzania, Dr Lieve Lynen, is remarkably modest. And yet more than 500,000 animals have been vaccinated against ECF in Tanzania since 1998, largely due to the

work of Lynen’s pharmaceutical company VetAgro Tanzania, which has led the way in promoting the ECF vaccine in the region for over 15 years. As a result of this achievement and a successful vaccine registration campaign, coordinated by the Global Alliance for Livestock Veterinary Medicines (GALVmed), veterinary authorities in Kenya, Uganda, Malawi and Tanzania have demonstrated renewed interest in vaccination as a means of ECF control.

Alfred Kapolo Kumai, a livestock keeper in Longido District in the north of Tanzania is one of the few livestock keepers who understand the disease well. He has enjoyed the benefits of the vaccine for quite sometime. “Before I started the immunization, I would lose about eight calves from a total of 10. Now I do not worry about that”.

Effective and affordableThe vaccination programme in northern Tanzania has resulted in over 80% of all calves vaccinated across many wards being protected for life.

Achieving this kind of success in a remote area with a vaccine, which depends on a cold chain for delivery, and costs up to US$10 per animal, is remarkable. But in Lynen’s view, the success should be credited to two main factors: the efficacy of the vaccine, and the willingness of the Maasai pastoralists to pay for the vaccine in order to

The vaccine has drasticaly reduced calf mortality from 80% to 2%.

L I V E S T O C K D I S E A S E C O N T R O L

BAOBAB ISSUE 58, JULY 2010 11

Fighting East Coast FeverLessons from Maasailand

BAOBAB ISSUE 58, JULY 201012

L I V E S T O C K D I S E A S E C O N T R O L

protect their herds and their livelihoods. “These are livestock keepers who know cattle and who know diseases,” she says. “They are willing to adopt a technology if it works - to commit themselves to a product where they see it gives them a future in livestock production.” VetAgro has a network of 90 delivery vets, trained in the ECF “infection and treatment” method and about to be officially certified. Lynen feels this is crucial in order to resolve concerns about mismanagement by some vaccinators, including use of ‘dead’ vaccine, which has been injected too long after removal from the cold chain, and cases of financial fraud.

Sharing the successNews of the efficacy of the ECF vaccine spreads quickly amongst the pastoralist community once vaccination begins to be adopted in an area, observes Lynen. However, VetAgro is also raising awareness through sensitisation days and use of film and radio.

VetAgro is keen to work with community animal health workers (CAHWs). Chosen and trusted by their communities, they are well placed to connect livestock keepers with certified vaccinators. A partnership with the Babati-based Community Animal Health Network is currently being developed by VetAgro to link with the many CAHWs who play an important role in alerting their communities to disease outbreaks and have been trained in recent years through various NGO programmes. Through this network, VetAgro hopes to extend the reach of CAHWs for organising and publicising vaccination days.

According to Kapoo Lucumay, a veterinary assistant and trained ECF vaccinator working in Longido district, Tanzania, arranging vaccination days is not difficult once livestock keepers are aware of the success of the vaccine. “It is the livestock keepers who arrange it,” he says. “They just talk and find out the number of animals they have between them. Then they phone and ask me to come and do the immunisation. There is no problem, because they already know the importance of this vaccine.”

ChallengesDeveloped 30 years ago, the ECF vaccine has been shown to be a highly effective product, with a 95 percent success rate in pastoral herds - one of the highest rates of protection offered

by any livestock vaccine. However, up till now, governments in East, Central and Southern Africa have not supported widespread adoption of the ECF vaccine due to the complexity of delivering the vaccine, which requires the vials to be stored in liquid nitrogen. Administering the vaccine also requires training as the vaccine is administered in combination with an antibiotic to allow antibodies to ECF to build up without the disease taking hold.

Maintaining the production and supply of the vaccine is seen as the key challenge to widespread vaccination, and such private sector involvement is an essential component. GALVmed is currently putting vaccination delivery out to tender in the private sector; inviting bids that will be scrutinised by a panel of organisations, including the African Union/IBAR and Pan African Vaccine Centre, which is responsible for quality control of all livestock vaccines on the continent. Hameed Nuru, GALVmed director of policy and external affairs, outlines what the panel will be looking for in the applications: “Number one, these business proposals have to be sustainable, we have to have continuity. Two - they have to be pro-poor, pricing the product for poor people. And three, distribution of the production must be for a defined area.”

The intention is that all aspects of vaccine production and delivery will be in private hands by the end of 2011. In the longer term, research is likely to focus on a new generation of vaccine that does not require the liquid nitrogen cold chain or the combined treatment with antibiotics.

Private sector futureOne vial of vaccine currently contains enough doses for 40 animals. In future, the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), which produces the vaccine, may look at developing a smaller vial of just five or eight doses, providing a more marketable product for private sector companies with an interest in setting up vaccination services.

The article was adopted from The “New Agriculturist” a WRENmedia production based in the UK.www.new-ag.info

Additional information from:www.infonet-biovision.org/default/ct/653/animalDiseaseswww.agfax.net/radio/detail.php?i=353www.galvmed.org/news-resources/content/east-coast-fever-vaccine-registered-tanzania

Cattle breeders in developing countries have been challenged to conserve valuable local breeds that can survive harsh conditions unlike imported breeds from industrialized nations. Given that genetic change has been a key driver of livestock developments in the north for the past 200 years, breeding promises even greater returns in the south today since it enables livestock farmers get out of poverty.

At the moment, the world’s livestock gene pool is shrinking and extinction of any breed or population means the loss of its adaptive attributes which are under control of many interacting genes. “With better and more appropriate breeds and species of farm animals, many of the 600 million plus livestock keepers in poor countries will be able to produce more milk, meat and eggs for the fast-growing global livestock markets thus pulling themselves out from poverty,” the International Livestock Research Institute’s Director General Dr. Carlos Sere observes.

According to him, sustainable breeding strategies that conserve local breeds can bring about higher smallholder milk production now than ever before. Of the more than 7,600 breeds recorded by Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), 190 have become extinct in the past 15 years and a further 1,500 are considered at risk of extinction. FAO estimates that 60 breeds of cattle, pigs, horses, goats and poultry have been lost over the last five years.

Of particular concern are the high rates of loss of indigenous breeds in developing countries, which, coupled with inadequate programmes for the use and management of these genetic resources,

is contributing to the reduction of livelihoods options for the poor.

New market incentives Addressing an international livestock conference in Nairobi, September 2009, Dr. Sere revealed that the existing new market incentives are presenting opportunities and challenges alike for developing countries.“Rising prices are driving more indiscriminate cross breeding, which is leading to the extinction of tropical breeds, as well as to poorly performing second and third generation cross bred animals,” he pointed out and observed that new science based breeding

T E C H N O L O G Y

A man conducts artificial insemination on a cow. Photo: Accelerated Genetics

Livestock breeding to increaseincome for small-scale farmers By Paul Sandys

BAOBAB ISSUE 58, JULY 2010 13

BAOBAB ISSUE 58, JULY 201014

technologies and policies that are now in place will raise smallholder dairy yields in sustainable ways while conserving valuable local cattle breeds.

A biotechnology expert and a former head of biotechnology at ILRI, Dr. Ed Rege, at the same meeting, advised scientists to evaluate and introduce the short, small and muscular hump-less West African N’dama breed of cattle in tsetse infested areas in East Africa. This is due to that fact that the breed, which is kept by farmers in free range village production systems across 20 countries in West and Central Africa, has developed resistance to the deadly diseases transmitted by tsetse fly. He also called for more widespread rearing of the Boran breed as opposed to other breeds in Africa due to its potential for high beef production.

Rege challenged scientists to provide farmers with good cows adding that the use of Artificial Insemination (AI), that has been underutilized lately, should be encouraged in providing appropriate breeding materials. “High demand for breeding females can be met through the use of AI, but only with more private sector participation,” he added.

He recommended that implementation of new agricultural ideas in future need to take a “bottom up” approach to ensure emerging best practices are developed in consultation

with farmers. He noted that new global trends in prices of livestock products are opening up opportunities for African small holder farmers. Giving the example of Kenya where 80% of milk is produced by small-scale farmers who own 6.7 million dairy cattle, he pointed that adoption of better breeding techniques would results in better adopted cattle in light of ongoing climate change.

Presently, Kenya is exporting milk powder to neighbouring countries in sub-Saharan Africa, South Africa, parts of Asia and the Middle East, markets that have huge potential for expansion. The achievements made in exploring these markets so far have been the result of increasing collaboration between farmers and relevant government departments on one hand and the establishment of private milk processing companies.

About the Author

Paul Sandys is a correspondent who writes on agriculture and livestock. He is based in Nairobi, Kenya. Email: [email protected]

T E C H N O L O G Y

Sere notes that the new science based breeding technologies and policies that are now in place will raise smallholder dairy yields in sustainable ways while conserving valuable local cattle breeds

Pastoralist cattle in Garissa, Kenya. Photo: ALIN

L I V E S T O C K : P O L I C Y I S S U E S

Pastoralism, the extensive production of livestock in rangelands, is carried out in climatically extreme environments where

other forms of food production are unviable. Providing a livelihood for between 100 and 200 million households, it is practiced from the Asian steppes to the Andes and from the mountainous regions of Western Europe to the African savannah. In total, its activities cover a quarter of the earth’s land surface. As well as generating food and incomes, these rangelands provide many vital, and valuable, ecosystem services such as water supply and carbon sequestration: services that are being degraded through misguided rangeland investments and policies.

Although some countries now officially recognize the value of pastoralism, negative perceptions still pervade. Pastoral policies are either non-existent or, where they do exist, are barely enforced. Establishing communal land tenure is crucial because it creates pastoral rights of access, provides opportunities for individuals to seek optimal ways of exploiting available resources, and facilitates changes in resource equity. However, the common property regime, which allows pastoralists to sustainably manage vast areas of land, is undermined by laws and policies that promote the individualization of land tenure. As a result, dry-season grazing reserves have been lost, livestock mobility has been restricted, land tenure has been rendered insecure and land degradation has increased, undermining the sustainability of the pastoral livelihood system.

Securing land tenure in Garba TulaThis past decade however has seen a promising shift by several governments to recognize and regulate access and tenure rights over pastoral resources. Improvements have been made in Niger (1993), Mali (2001) and Burkina Faso (2002). Mongolian government policy now supports communal land tenure through placing greater control of natural resources in the hands of customary institutions [see box]. Benefits have impacted both pastoral livelihoods and the conservation of herders’ rangeland environments. Against this backdrop, it is important to identify and support processes that can help strengthen the governance of pastoral systems, as well as local land use and the environment. Pastoral societies also need to find more equitable ways of including pastoralists in the policy-making processes, as well as in the design of technologies and the make-up of the customary institutions that shape

Pastoralism By Jonathan Davies and Guyo M. Robashifts in policy making

BAOBAB ISSUE 58, JULY 2010 15

Camels - handy animals for pastoralists. Photo: Jonathan Davis

Pastoralism provides a living for between 100 and 200 million households, from the Asian steppes to the Andes. But misguided policies are undermining its sustainability. Baobab

asks how governments can best strengthen the governance of pastoral systems and find more equitable ways to include pastoralists in policy making. Land tenure and joint

management prove crucial to the answer.

livestock production systems and environmental governance.

In Garba Tula in northern Kenya, weak land tenure was identified as one of the key obstacles in the bid to improve the livelihoods of the region’s 40,000 predominantly Boran pastoralists. Garba Tula, an area extending over around 10,000km2, has extraordinary biodiversity, but the full potential to conserve it was not being met, and people and their livelihoods were threatened by wildlife. In an initiative that emerged from meetings held by community elders in 2007/8, a Community Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) approach was set up to strengthen tenure. Spearheaded by a Community Task Force and strengthened by expert-facilitated consultations, the community arrived at a common understanding of CBNRM as “a way to bring local people together to protect, conserve and manage their land, water, animals and plants so that they can use these natural resources to improve their lives, the lives of their

children and that of their grand children”. The strategy should improve the quality of people’s lives “economically, culturally and spiritually”.

Land in Garba Tula is held in trust by the County Council, but county councils generally exercise strict control over the allocation of land and

are poorly accountable to local communities who in turn are poorly informed of their rights. Contrary to popular perception, trust land is not government land and it can provide a strong form of tenure if the community understands both its rights and the legal mechanisms to assert them. Garba Tula residents now document their customary laws and are encouraging the County Council to adopt them as by-laws. This will also

provide a foundation for developing a range of investments that are compatible with pastoralism, such as mapping wildlife dispersal routes; residents are also interested in ecotourism.

The Community Task Force is setting up a local trust to manage the process and the painstaking procedure of ensuring community and local government buy-in is supported by a number of development, conservation and wildlife agencies as well as government. Since the vast majority of Kenya’s drylands are legally trust land, the Garba Tula experience could set a precedent for securing land tenure in other areas.

Encouraging community engagementPolicies and institutions must empower pastoralists to take part in policy-making that affects their livelihoods. This will also promote equitable access to resources, facilities and services, and guarantee sustainable land use and environmental management. The right pastoral policies will also aid the process of

Mixed herds such as this one are common in East African range lands. Photo: Jonathan Davies

L I V E S T O C K : P O L I C Y I S S U E S

A boy herding camels. Photo: Jonathan Davies

BAOBAB ISSUE 58, JULY 201016

democratization and ensure improved governance in pastoral areas. In addition to addressing issues related to livestock production, health and marketing, pastoral policies should also tackle critical issues such as healthcare, education, land rights and women’s rights as well as governance, ethnicity and religion. An important lesson from Garba Tula is that the policy environment may be more supportive than imagined, and what is missing might not be the policies so much as the capacity for taking advantage of them.

Published research on African pastoral systems has steadily overturned many of the misconceptions about pastoral systems, highlighting the importance of appropriate strategies to manage the variability of the climate in dryland environments. Effective management strategies will allow for diverse herds of variable size and keep them mobile. There are increasing opportunities for pastoralists to capitalize on environmental services such as the maintenance of pasture diversity, vegetation cover and biodiversity through ecotourism or through Payments for Environmental Services. The Kenyan example shows that even in Africa, where competition over public funds is tough and such schemes are poorly supported, the situation can be changed through community empowerment and government accountability.

About the authors

Jonathan Davies ([email protected]) and Guyo M. Roba ([email protected]) both work in Nairobi, Kenya, for the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Davies is Regional Drylands Coordinator, Roba is Programme Officer Drylands.

Reduced vegetation cover is a threat to livelihoods in dry lands. Photo: Jonathan Davis

Policies and institutions must empower pastoralists to take part in policy-making that affects their livelihoods. This will also promote equitable access to resources, facilities and services, and guarantee sustainable land use and environmental management.

BAOBAB ISSUE 58, JULY 2010 17

BAOBAB ISSUE 58, JULY 201018

It’s important for you to think of the

future. Right now it is raining, but a time will come when there will be no rain. Then there will be no grass for

your animals.

I encourage you to cut grass, dry it and make hay, then store it away. Your cows and goats will

feed on that when the rains stop

Wow! I have learnt a lot

today! I’m going to cut grass and dry it, just

as OFISA said

Aaagh! That’s too

much work! I’m not going to

do that!

PAAH! Too much

work!

Stork story

S T O R K S T O R Y

This life is hard! Why is this happening? It hasn’t rained for

four months!!

some months later...

there’s no grass for my

animals!

Eh, Wangombe, your animals

are not dying?

Ah, here she is! She had

promised to come today to see how we

are doing

HAllo!

I should have listened to you.

My animals are all dying!

It’s always good to listen

and apply techni-cal advice from

ofisas!

No, they are all doing well. I’m feeding them on the hay I made.

Just as oFISA advised us. I can give you some grass

for your animals

BAOBAB ISSUE 58, JULY 2010 19

BAOBAB ISSUE 58, JULY 201020

Phalombe is a district in the South Eastern part of Malawi part of which lies below the Mulanje Mountain while the other

part borders Lake Chilwa and Mozambique. The majority of the people rely on subsistence farming. Recently however, increasing population pressure on land for farming is forcing more inhabitants to go into fishing for food and to earn a living.

While fish farming may be an alternative to crop farming for food, a sizeable population in Waruma community in Phalombe District has their own story to tell. They have for the past five years been working with a church development organisation in the name of Blantyre Synod to promote small-scale farming for food and household income generation. The project targets vulnerable members of the community such as the elderly, disabled, people living with HIV and AIDS and women. These categories of people generally have less energies or resources to work on farmland. The church has supported them to raise goats, local chicken and guinea fowl for food to improve their nutrition and generate income.

How it is done Village committees identify eligible household members who are given either of the livestock for breeding. Those that get a goat are encouraged to construct a goat house raised off the ground that allows goat droppings slip through to the ground. This reduces concentration of urine which may result in accumulation of diseases in the house.

In some circumstances the goats are allowed to graze freely in the community compounds. Supplementary feeding is done through the provision of maize bran mixed with salt. This is a cheaper way of raising the goats since little time is spent caring for them. The system also promotes cross breeding with goats from other compounds. This could be advantageous to families that aim at increasing their animal vigour.

Experience has it that one female goat will give birth three times in 24 months. By the time the goat gives birth for the third time the firstborn kid will have been mated. A mature fully grown goat will fetch an average of $50. This is no small achievement for a subsistence farmer. The money could buy three 50 kg bags of maize grain, which is the staple food for this community. Village committees make arrangements for the first kid to be passed on to another deserving farmer in a nearby community. In this way the process continues to benefit a wider community.

Small-scale livestock development has also been linked to Integrated Aquaculture Agriculture (IAA). This allows livestock to grow and graze within fish pond areas. The goats and chicken droppings are thrown into the ponds that eventually support the growth of small plants under water (zooplanktons) that become feed for fish. Fish is harvested every six months for food or sale. This integration brings mutual dependency and maximizes farmer benefits.

livestock Small-scale

productionby Wellings Mwalabu

A livelihoods perspective in Phalombe District - Malawi

O N T H E S U B J E C T O F

BAOBAB ISSUE 58, JULY 2010 21

General advantages Small-scale livestock development can be achievable with little inputs yet more benefits for poor households. The droppings from goats and chickens make up a concentrated base of compost manure, which can improve the growth of various vegetation in the community homes including, nourishing fish ponds. The practice requires only small spaces and less labour yet the production becomes immensely large. Small stocks reproduce prolifically therefore the numbers increase very quickly.

The practice allows a subsistence farmer to diversify his sources of income besides diversifying household diet. In a typical rural area where

employment opportunities are limited households keeping a diversity of livestock stand better chances to increasing household income thereby mitigating hunger especially in the lean months of December through March. The raising of small-scale livestock is therefore one quick step towards achieving sustainable livelihoods for most vulnerable community members of the community.

About the Author

Wellings Mwalabu, Church of Central Africa Presbyterian Blantyre Synod, Malawi

Email: [email protected]

A farmer gives supplementary feed to his goats after free grazing-in the background raised goat kraal constructed from local materials; Blantyre Synod project - Malawi

A small holder farmer taking care of her turkeys; Blantyre Synod project-Malawi

Integrating livestock development into fish farming; Blantyre Synod project - Malawi

BAOBAB ISSUE 58, JULY 201022

Let’s talk about

AIDSHIV and AIDS has become part and parcel of our lives. We all know someone living with HIV and AIDS or has been infected or affected by the condition. The agriculture sector has also been affected by it and therefore the need for harmonious treatment of those infected. Below is a case study of how ACORD Northern Uganda - Gulu has dealt with stigma and discrimination.

General BackgroundPeople living with HIV and AIDS (PLWHA) have a critical leadership role in challenging HIV and AIDS related stigma and discrimination. To effectively participate in processes that address stigma and discrimination, it is vital that PLWHA understand how stigma is manifested as well as be equipped with the appropriate skills to challenge it. Capacity building is central to this.

This case study illustrates the important role that building the capacity of PLWHA played in a project that centered on addressing the rights of PLWHA, with a focus on HIV related stigma and discrimination. The one-year project was implemented by Agency for Cooperation and Research in Development (ACORD) in Gulu district in collaboration with the Gulu District Network of PLWHA.

The PLWHA in Gulu District have long been facing perpetual neglect and discrimination. The Government as well as other development agencies have excluded their needs from development plans. This was, in part, due to

their limited awareness and knowledge about their rights as well as absence of the appropriate advocacy skills. The district PLWHA network lacked the required resources needed to mobilise the rest of the members resulting in a communication gap, which consequently lead to the disregard of PLWHA views. They also lacked skills to effectively engage in lobbying and advocacy for their rights. Capacity building, therefore, became the necessary key tool for building up a strong network of PLWHA.

Capacity building targeting PLWHA entailed skills building workshops on stigma and discrimination; exchange visits to other networks within the country for experience sharing; provision of office space and equipment for the district PLWHA network, as well as facilitating representatives of the network to present their views about their rights during various district, national and regional forums. These interventions were the key capacity building entry points for PLWHA networks to engage with the district and other development agencies in order to advocate for their rights and entitlements. The capacity of members was also enhanced through close professional interaction with ACORD staff, which, in part, contributed to the development of skills and confidence.

Objectives

Capacity building was carried out with the following strategic objectives:

• EquippingPLWHAandlocalleaderswithenough information about their rights in order for them to effectively address HIV and AIDS related stigma and discrimination

F A R M E R S ’ H E A L T H

Capacity building for People Living with HIV and AIDS - a prerequisite in fighting stigma and discrimination.

BAOBAB ISSUE 58, JULY 2010 23

• Improvecoordinationandnetworkingskillsfor the PLWHA networks

• EnsuringthatalltheotherPLWHA(includingmembers and non-members of the district network) receive the required information from those who attend capacity building workshops during community meetings

• EnsuringthatthePLWHAknowwhatactionsto take if and when their rights are violated

• ImprovingadvocacyskillsofPLWHA

• DocumentationoftestimoniesofPLWHAin order to share with others

• Enablingmembersfromdifferentlocationswithin the district to meet and share experiences

Approach

In order to build capacity for PLWHA in Gulu district, ACORD started by organizing a consultative meeting for the PLWHA district network executive so as to introduce the project as well as assess the training needs. As part of the consultative meeting, the research report Understanding and Unraveling HIV Related Stigma and Discrimination was presented and formed the basis for initiating the project. Using this process, the specific areas of focus for PLWHA in Gulu district were identified and formed the basis for the skills building programmes. During the consultation, PLWHA also identified the participants for the workshops who included the PLWHA leaders at district level and the sub county political leaders. ACORD recognized that, as leaders, these participants would be in position to effectively put in practice the different skills acquired from the workshops.

The skills building workshops focused on a wide range of issues identified by the PLWHA that related to their rights. These included understanding stigma and discrimination; rights of PLWHA as human rights; will writing and coordination and networking and advocacy.

The skills building workshops were facilitated by PLWHA who have knowledge and experience in lobbying and advocating for rights of PLWHA as well as vast information on current debates and other processes at the national level. Some of the facilitators were also selected from within Gulu including staff from Ugandan Human Rights Commission (UHRC) and The Aids Organisation (TASO) as they were highly familiar with issues of stigma and discrimination in the local context.

To further strengthen skills acquired during the workshops, participants were then exposed to experiences from other regions through review meetings with the district network of PLWHA in Mbarara Western Uganda. The Gulu district network of PLWHA was also provided with office space within the ACORD premises which gave them an opportunity to be mentored and gain skills in various areas through working closely and regularly with the ACORD HIV and AIDS focal officer.

Factors that facilitated effective capacity building

Resource availability

Sufficient human, logistical and financial resources were the basic initial requirements used in the enhancement of capacity levels of PLWHA. With sufficient support from the Ford Foundation, ACORD was able to conduct the training workshops and as well facilitate various processes that lead to the exposure the PLWHA to different forums for experience sharing and learning and ultimately, skills building.

The skills building workshops focused on a wide range of issues identified by the PLWHA that related to their rights.

Access and availability of communication mediums and facilities

Easy access and use of communication facilities was and is a necessary factor to achieving effective capacity building. To achieve this radio and telecommunications mediums were used to mobilize participants for the workshops. Developing networks with the media (particularly radio - as this is the most efficient communication medium) enhanced the frequency and ease of communication, which in turn enhanced capacity building.

Selecting the right target Group

Identifying and selecting the right target group that will have the capacity to absorb, fully utilize lessons learned. In this case, PLWHA were identified through consultative meetings and were expected to give feedback to their colleagues during community meetings and the local leaders who were to mobilize and sensitize the community. ACORD Gulu, in collaboration with the district network, selected leaders of PLWHA from different associations in Gulu district and the sub county Chairpersons to participate in a workshop on stigma and discrimination. The leaders developed an advocacy strategy and plan of action to be implemented in their respective constituencies.

Relevancy of skills training

Capacity building initiatives are likely to be more successful in situations where they are relevant to the identified information needs of the target population – in this case, PLWHA. The PLWHA leaders in Gulu shared the information gaps during the skills building workshop. As a result, subsequent workshops focused on identified information needs that led to more interest by the leaders and enhanced their desire to learn and share the taught information and skills.

Availability of Skills training materials

Developing short and well-designed manuals or training materials and other Information Education and Communication (IEC) materials is important. These can act as a guide during

the trainings and provide all the necessary information for the facilitator. ACORD HIV/AIDS Team compiled guidelines on various aspects related to HIV and AIDS care and support for PLWHA, which they used for PLWHA skills workshops.

Drawing clear plans and holding regular planning meetings

ACORD in Gulu held a number of consultative meetings with the PLWHA leadership and the local councilors that focused on assessing information needs. These events generated issues related to HIV stigma and discrimination and were subsequently incorporated in the workshop curriculum which facilitated a clear planning process and ensured effective implementation of the capacity building process amongst the targeted PLWHA district network.

Use of competent training facilitators

Having competent facilitators who have the relevant knowledge, experience and training skills for the planned topics. ACORD used highly trained facilitators who were mainly PLWHA (as they would identify greatest with those facing stigma and discrimination) who have adequate training.

Monitoring progress

Establishing a strong monitoring framework coordinated by PLWHA who are responsible for conducting follow-ups to assess the effectiveness of the capacity building process. The district network, in collaboration with ACORD, held quarterly review meetings for assessing progress in the different PLWHA associations. The review meetings were utilized to identify challenges as well as plan for subsequent periods.

Outcomes of the capacity building processes • Throughtheworkshops,PLWHAdeveloped

confidence to share their personal experiences by giving oral testimonies. These were documented and developed into materials on violation of rights of PLWHA, which

F A R M E R S ’ H E A L T H

BAOBAB ISSUE 58, JULY 201024

will continue to be vital advocacy tools for the rights of PLWHA. The documented testimonies are important for purposes of lobbying to policy makers in order to draw their attention to the needs of PLWHA and to the existing policy gaps leading to the violation of rights of PLWHA.

• ThedistrictPLWHAnetworkdevelopeddocumentation and analytical skills. For instance, they were able to conduct a needs assessment and situation analysis of members with the objective of coordination and improvement of service delivery.

• AIDSserviceprovidersinthedistricthavestarted using the PLWHA networks in the sub county as their entry point for service provision.

• Theengagementofthemediaintheworkshops has scaled up information dissemination amongst the community about the project focusing on the roles of the PLWHA district and sub county networks. A lot of advocacy work has also been done through the involvement of the media in the capacity building workshops; e.g. the issue of nutritional support to PLWHA had been a very serious problem and some of the PLWHA names had been deleted from the beneficiary lists. During one of the capacity building workshops, the media recorded the message from PLWHA that had experienced

this and played it on radio using spot messages and, resulting from this, some PLWHA have reported positive response from the responsible organizations.

• ThePLWHAnetworkhasbeenequippedwith knowledge, skills and information for

coordination with other partners. They now have the confidence to lobby for all the necessary support from all service providers. They have managed, so far, to get support from Northern Uganda Malaria AIDS and TB programme and, at sub county level; some of the groups have been lobbying and getting support. The network now works regularly and has developed partnerships with other organizations like National PLWHA Forum (NAFOPHANU).

For more information contact:

Dennis Nduhura Program Manager ACORD HASAP [email protected]

Jacinta Akwero Program Officer HIV/AIDS, ACORD Gulu [email protected]

Abwola David Sunday Tech. Advisor HIV/AIDS ACORD, Gulu [email protected]

These events generated issues related to HIV stigma and discrimination and were subsequently incorporated in the workshop curriculum

BAOBAB ISSUE 58, JULY 2010 25

BAOBAB ISSUE 58, JULY 201026

Pig farming in the rural areas is an important economic activity that can involve all members of the family and provide much

needed income. A farmer from Lukwanga parish, Wakiso district of central Uganda shares experiences in small-scale pig farming and highlights the advantages, challenges and lessons learned.

Pig Farming Methods

Pig farming under a tree shade

Farmers in Lukwanga have traditionally reared pigs through this simple technology.

Method

Select a tree with good canopy to shield the animal(s) from direct sunlight. Tether the animal(s) under the tree and provide appropriate feed (zero grazing) and water on a regular basis. In Lukwanga mango and jackfruit trees are well known for providing the best shade for pig rearing.

Advantages

The system is cheap and easily affordable to majority of farmers.

Challenges

• It is difficult to maintain cleanliness especially during the rains. As a result worms infest the pigs and the farmer incurs the costs of treatment.

• The pigs waste a lot of time searching the soil for worms and other insects; this distracts them from feeding and affects the yields.

• Feeds are lost through trampling and scattering by the animals.

• It is difficult to tap the urine and dung for manure that can improve crop yields.

Deck piggery

A deck piggery for sheltering the animals is easy to construct using the following materials and method:

Materials

Nails and a hammer; a hoe; 10 poles and enough timber for fencing the deck; measuring tape and string; polythene sheet for roofing the deck.

Method

• Choose a raised and gently sloping site where water can easily flow out

• To provide space for two pigs mark out an area measuring 5 feet by 8 feet

for Income Generation in Lukwanga, Uganda

Pig Farming Small-scale

By Ndugga Evaristo

Pigs reared in a locally made piggery unit in Lukwanga ,Uganda. Photo: Ndugga Evaristo

T E C H N I C A L N O T E

BAOBAB ISSUE 58, JULY 2010 27

• Using the tape and string, measure out 10 pole points (3 poles each at the front and back and two poles each on either side of the deck). The poles should be approximately 2.5 feet apart

• Dig holes for the poles

• Fix three poles measuring 8 foot high at the front of the deck and three poles measuring 7 foot high at the rear end of the deck

• Tie strings between the front and rear poles on either side of the deck

• Fix two poles on the left side of the deck and two poles on the right side of the deck, using the string to maintain uniform height

• Fence the deck with timber, spacing it in such a way that the animals including young ones cannot move out of the deck

• Cover the deck with the polythene sheet to shield the animals from the sun and prevent rainwater from leaking in

Advantages

It is easy to maintain cleanliness and the shade helps the animals to relax after eating, giving them a faster growth rate.

Challenges Some of the construction materials need to be purchased and this makes the system more costly.

In addition feeds can be lost through trampling and scattering by the animals.

Penny Construction

This is a modern farming system with a permanent structure that requires relatively more expensive inputs but has greater expected outputs.

Materials

Cement and sand; sand baked blocks; nails; block slate stones; iron sheets; wooden doors; timber; water; tools for masonry and timberwork.

Labour

A person with some experience in masonry will be required.

Dimensions of the penny

• The standard size of each room should be 7 feet by 12 feet with a roof measuring 8 feet high

• Allow enough space in each room for the pigs to drop dung and access sunshine

• Construct a channel for the urine to flow into the reserve tank

• Construct permanent drinking and feeding trays within each room.

Advantages

• It is easy to maintain hygiene standards and this enables the pigs to grow healthy and fast

• Cleaning the pennies, which should be done at least once a day, is easier

• The dung and urine can be collected for use as organic manure

• The penny offers better shelter and security for the pigs.

Other key factors in pig rearing

Number of pigs reared

The number of pigs reared will depend on the farmer’s ability to feed them. It is however advisable to begin with three pigs consisting of two females of the same size and age and one male

A pig feeding on potato leaves. Photo: Ndugga Evaristo

BAOBAB ISSUE 58, JULY 201028

that is slightly older than the females. The male should not be genetically related to the females.

Signs of heat in female pigs

• Swelling of the genitals

• The pig is hostile and runs after any male(s) in proximity

• Feeding habits change and the animal loses appetite.

Gestation period

The average gestation period for pigs is approximately 104 days. High breed pigs produce an average of 6 to 12 offspring per delivery. Young pigs can be allowed to suckle their mother for one month, and if properly fed the mother should be on heat two months after delivery.

Weaning

Pigs weaned at an early stage are weak and do not perform well.

Record keeping

It is advisable to note the date when a male serves a female; this helps the farmer to identify the possible date of delivery and to be on the lookout so that the female does not eat the placenta after delivery. Eating the placenta reduces the amount of milk produced by the female, leading to poor growth of the offspring. The records should also indicate types of feeds, feeding regime and age of pigs, among other details.

Feeding

• Pigs need to be properly fed if good results are to be obtained, therefore it is difficult to rear them during periods of food crisis.

• Examples of nutritious feeds for pigs include household leftovers, agricultural residues, sweet potato leaves, damaged cabbages, banana and cassava peals. Red skin from cassava should however be removed before cassava is fed to pigs.

• The pigs should be supplied with water daily.

• Feeds should be properly mixed; an example of feed mixture is given in text box 1.

Treatment

• Deworm the pigs after every two months

• Spray the pigs regularly to avoid skin diseases

• Keep the pennies clean to avoid attacks from safari ants

• Contact a veterinarian for advise if the animals are sick or fail to perform well.

Marketing

The cost of a pig will depend on the breed, size and ability of the buyer or seller to bargain. In Lukwanga for example, a two months old pig can be sold for between 35,000 - 40,000 Uganda shillings if well maintained. Pork costs between 4500 – 6000 shillings per kilogramme in Lukwanga.

Challenges in pig rearing• Although pig rearing is profitable it is time

consuming since the animals require daily care. Majority of farmers are involved in subsistence agriculture and the pigs compete with crops for the farmer’s attention.

• Capital input is necessary especially for deck piggery and penny construction and purchase of feeds.

• Obtaining quality breeds of pigs is not easy.

A pig smeared with oil and grease to kill off lice. Photo: Ndugga Evaristo

T E C H N I C A L N O T E

BAOBAB ISSUE 58, JULY 2010 29

Although different breeds are offered for sale some farmers do not give the young pigs enough milk and feeds and this affects growth and performance of pigs.

• Getting a good market for the pigs is challenging as some buyers might offer extremely low prices. Sometimes farmers are forced to sell off the pigs at low prices since they need to dispose off mature stock, or to get money for subsistence, purchasing feeds and paying for treatment.

Lessons learnt• Pigs are relatively fast growing animals

depending on the quality of breed, type and quantity of feeds used; hence they give faster returns on the investment.

• Farmers should carefully select pig stock for rearing to avoid poor breeds and diseased or weak pigs.

• Pig farmers should be aware of incurable diseases such as swine fever; they should carefully note any reported incidences of such diseases and take preventive measures to avoid infection of their pig stock.

About the author

Ndugga Evaristo is a member of Lukwanga Community Knowledge Centre and pig farmer in Nabukalu village, Lukwanga parish, Wakiso district, central Uganda. Tel: +256 774118845

Traditional way of rearing pigs that exposes them to diseases. Photo: Ndugga Evaristo

The cost of a pig will depend on the breed, size and ability of the buyer or seller to bargain.

BAOBAB ISSUE 58, JULY 201030

Why has ileia decided to let partner organisations manage regional magazines?We are confident that other organisations can take forward the work that we started as a global magazine 25 years ago. We also feel that local editions will include content that is more relevant to local farmers. Partners for Farming Matters now produce local editions in Latin America (Peru and Brazil), West Africa (Senegal) and Asia (India, China and Indonesia). By merging Baobab and KEA, we now have ALIN as the partner for East Africa. The other reason is that recent readers’ surveys have indicated that although there are many readers of Farming Matters in East Africa, they would like to have more local content. So it is a natural step that there are magazines on sustainable small-scale agriculture that are strongly rooted in the respective regions but which are still connected to our family of magazines.

Now that the magazines are more regional, what is your role as the global edition?We shall still remain connected with the regions and be ready to carry content from regional members of the AgriCultures network in Farming Matters. For instance, the Maarifa (Knowledge) centres concept being used by ALIN in East Africa presents a unique approach to sharing best practices in small-scale agriculture that could be adopted in other regions. We therefore would like to learn from you and use Family Matters to spread these ideas in a global context. We have a new role to play in that sense.

What is the AgriCultures Network?“AgriCultures” is coined from two words - “agriculture” and “culture”. We believe that agricultural practices in different parts of the world are also influenced by the respective cultures of those communities. In East Africa for example, cultures prevalent in arid lands are different from those practiced in high potential areas. We believe that there is no single type of agriculture that can address the different challenges facing the world today such as food crises, climate change, or even increasing water shortage. These can only be tackled through a diversity of approaches to agriculture, which are relevant to local cultures.

G U E S T C O L U M N

Interview with

Director ileiaBy Susan Mwangi

Edith van

Walsum

BAOBAB ISSUE 58, JULY 2010 31