Auyero2002_Judge,Cop, And Queen

-

Upload

laura-radicchi -

Category

Documents

-

view

213 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Auyero2002_Judge,Cop, And Queen

The judge, the cop, and the queen of carnival:Ethnography, storytelling, and the (contested)meanings of protest

JAVIER AUYEROState University of NewYork at Stony Brook; Centro de Estudios en Cultura y Pol|tica,Fundacion del Sur

The objects of desire

` This is for you,'' Nana, a 39-year-old employee at the state court-house, said as she handed me a crystal from a chandelier in the Gov-ernment House. ` I took it as a souvenir when we occupied and burneddown that corrupt house . . . keep it as a memento of my Santiago.''Caught by surprise, I asked her, ``What does it mean to you?'' ` It's akeepsake,'' she answered, ` and I'm really happy because you're inter-ested in it. That means that it is a valuable keepsake. At least it's useful,because you are interested in it. It's a souvenir. I said to myself, `I willgo there (into the burning Government House) again, because I want asouvenir.' What does it mean to you?''

This was our last interview in what is now a ¢fty-page transcript of herparticipation in the Santiagazo, a riot that shook the northwest Argen-tine city of Santiago del Estero on December 16, 1993. During this ` dayof fury,'' as local commentators named it, thousands of demonstrators(most of them public employees faced with a mounting threat to theirlivelihood and claiming their unpaid wages) invaded, sacked, andburned the Government House, the legislature, the courthouse, andthe homes of nearly a dozen prominent politicians, o¤cials, and aunion leader.

`After that day,'' Mario (at the time an o¤cer in the local policedepartment) told me, ` I began searching for the objects stolen fromthe Government House. Right away, my superiors ordered me torecover all the stolen things.'' The fact that most of the valuable objects(not incidentals like the crystal that now hangs in my o¤ce) that Mario

Theory and Society 31: 151^187, 2002.ß 2002 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in the Netherlands.

found were in the possession of powerful people (` friends of power,'' ashe put it) led to his removal from the police force. Part of his anger atthis arbitrary decision was vented in our two-hour talk during thesummer of 1999. Throughout our long conversation, he insistentlysought to ``set the record straight about what happened.'' ``That day,my career was crushed,'' Mario sadly told me, ` and I want to tell youmy version of the story'' (see Figure 1).

Based on a series of in-depth interviews and informal conversations Icarried out during the summers of 1999 and 2000 in the city of Santiagodel Estero and research conducted in the archives of Hemeroteca delCongreso Nacional, in Buenos Aires, and the newspaper El Liberal, inSantiago del Estero,1 this article examines the source, form, and im-pact of the stories that journalists, state o¤cials, and protesters tellabout the riot. The article's aim is two-fold. First, it reconstructs partof the history and impact of the most violent ` austerity protest''2 incontemporary democratic Argentina. The Santiagazo was a highlyunique event in modern Latin America: a ` riot'' that was the ¢rst tocombine protest against austerity measures and widespread publiccorruption, converging on the residences of wrongdoers and the sym-

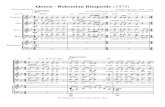

Figure 1. ` . . . that corrupt house.'' Government Palace, Santiago del Estero, December16, 1993.

152

bols of public power; a riot of ``hungry and angry people'' ^ as themain Argentine newspapers described it ^ in which (almost) no storewas looted and there were no human fatalities.3 Although unique, theSantiagazo was hardly an isolated phenomenon. With the regionaleconomies in complete disarray4 and the slashes in public spendingrequired by structural-adjustment policies,5 the last decade witnessedthe generalization of ``social explosions'' (raging from prolonged roadand bridge blockades to sieges of public buildings) in the south (theprovinces of Neuquen, Rio Negro, Santa Cruz, Tierra del Fuego) andnorth of Argentina (the provinces of Jujuy, Salta, Tucuman, La Rioja,Formosa, and Corrientes).6 During the last decade, the interior of thecountry has become a veritable landscape of protest. Second, analysisof the stories of the riot, and of the di¡erent meanings that a singlecontentious episode can acquire, should help us re£ect more broadlyon the relations among storytelling, memory, and actors' self-under-standings.7

Social scientists have taken good advantage of storytelling,8 mainlyemphasizing its potential as a window into the meanings of extremelydiverse collective and individual practices, from killing cats to readingthe Bible, from cock¢ghting to prize¢ghting.9 Collective action scholarsare also increasingly paying attention to narrative. Stories/narrativesare crucial not only in creating the possibilities for collective action (inplotting, for example, the political opportunities to act, in framing` objects, situations, events, experiences, and sequences of action''10)but also in constructing the experiential meanings of events after thefact and thus the self-understandings of those who, on either side,participated in it. Narratives are, as Robin Wagner-Paci¢ci11 wouldput it, one of the forms in which contentious memories come to us.

Five years after the Santiagazo, Nana went to a union meeting in Mardel Plata, Buenos Aires' main beach resort, invited by a left-wing unionorganization to talk about her contentious experiences. ``That year,''she told me, ``I saw the ocean for the ¢rst time.. . . I used to write poetryabout the ocean without having seen it. Maybe the muses exist, andyou are not the author of what you trace.'' Nana was not talking aboutthe riot, but what she said could be applied perfectly to the events ofDecember 16 and to the multiple meanings that its protagonists (pro-testers, law enforcers, state o¤cials, etc.) have been constructing sincethat day in their ` contest for gaining control over the interpretation'' ofthe episode.12 Drawing upon Steinberg's work and critically trans-lating the insights of the recent ` relational turn'' in the sociology of

153

collective action13 this article examines the di¡erent characterizations,explanations, and interpretations of the event.

The existence of di¡erent versions of big events (riotous or otherwise)is hardly news. As Vera Zolberg perceptively puts it in her study of thecontroversy surrounding the Hiroshima exhibit: ` Reading the past isnever a simple matter, even when the events composing it are agreedupon by most who try to decipher it. Events themselves are only someof the ingredients that history comprises, and they rarely stand inpristine solidity, but are ¢shed out from a sea of seemingly weedlike,tangled occurrences.''14 However, little has been said about the ways inwhich, during the labeling process, stories are constructed in explicitcontrast to each other, not only (or mainly) in terms of the facts butalso in terms of the meanings ascribed to these facts. I argue that thisprocess of meaning-construction is a deeply relational/dialogical pro-cess, a process that takes the form of a ``rhetorical sparring''15 ^ or, inTilly's felicitous formulation, a ``contentious conversation''16 ^ amongpowerholders, the media, and protesters.17

The ¢ghting words matter not only because they are the stu¡ throughwhich the riot is continually constructed. Protesters' stories, theirrecollections, are also crucial for the construction of the sense of whothey are, i.e., their ` self-understandings'' or their ` situated subjectiv-ity.''18 Stories, then, are central in the construction of the riot and ofthe rioters. As Polletta19 clearly puts it, ` narrative's con¢guration ofevents over time makes them important to the construction and main-tenance of individual and collective identities.'' For the case at hand,the implications of Polletta's analysis are quite relevant: what hap-pened during that ` day of fury'' and who the actors are/were are deeplyentangled questions. Furthermore, whether the chandelier crystal, thegovernor's desk, or his wife's fur coat (to name a few of the ` keep-sakes'' mentioned by protesters) are ``souvenirs'' to be kept, objectsdevoid of meaning, or things to be recovered depends not only onwhich side actors were during the event, but also on the version(s) ofthe event that they have created since then.

Just as Durkheim disposes of the idea of the lonely suicidal individual,current developments in the sociology of memory20 reject the existenceof mnemonic Robinson Crusoes.21 The relational setting in whichactors are located a¡ects the depth, tone, and the very facts of theirmemories.22 Memory is thus socially and intersubjectively struc-tured;23 re£ecting about this character is, Robin Wagner-Paci¢ci ar-

154

gues, a mode of thinking about power relations.24 Halbwachs high-lights this aspect of collective memory but also points toward itsstructuring character, saying that a shared identity is maintainedthrough the act of remembering. In reshaping (and reinventing) memo-ries, members of a group create boundaries and ties among them-selves.25 This article takes heed of recent developments in the sociologyof memory, to explore this double character of the memories of con-tention focusing upon the dialogic sources of memories and their e¡ecton the construction of identities.

Despite Polletta's and Steinberg's detailed attention to narrative anddiscourse, and probably because their works are based on archivalresearch, neither of them concentrate their attention on those towhom stories are told. By focusing on the ethnographic encounter as aspace of retelling, this article argues that the interview not only facili-tates the emergence of meanings that would otherwise be lost but alsoprovides a window into the type of identity work performed by stories.The interview allows us to see how people like Mario ^ the policeo¤cer ^ and Nana ^ the angry protester ^ live within the stories theytell: the sense of who they are is marked by ` their'' stories of the riot.The recollections of the riot will thus be approached as ` collectivememory'' in Halbwachs's sense of the term, i.e., as an active past thatforms the actors' self-understandings. The link between storytellingand identity-construction, I argue, operates in full force during theethnographic interview; we should thus examine the role of the socialanalyst in the interactive reconstruction of the meanings and identitiesof collective protest, a role that, despite comprehensive treatments ofthe scope and workings of ` qualitative methods,''26 has been ratherunderexplored.

In the ¢rst part, after a brief description of the employment structureof the city of Santiago and the level of government corruption thatpredated the uprising, I reconstruct the stories that journalists, politi-cians, and a prominent judge tell about the same episode, stories that ^in combination ^ constitute an ``o¤cial memory.'' To speak about an` o¤cial point of view'' of the events ^ the ` point of view of o¤cials andwhich is expressed in o¤cial discourse''27 ^ does not mean that Iconsider this story to be a monolithic and cohesive one. The story ofthat day and its e¡ects as told by a police o¤cer seeks to illuminate thislast point. My reconstruction, however, emphasizes the agreementsrather than the di¡erences, because it is based on these agreementsthat protesters construct a contentious dialogue. The rhetorical spar-

155

ring that takes place between this o¤cial point of view and the morefragmented stories told by participants in the riot is the main subject ofthe second part of the article, where I pay special attention to twoparticular meanings of the riot: a) the carnivalesque dimension thatantagonizes the o¤cial discourse's emphasis on the ` sad character'' ofthe day; and b) the respect and dignity that protesters claim they weresearching for in the riot, and that the o¤cial memory dismisses when itspeaks of a ` mere wage claim.'' In the last part, I explore the role ofethnography in bringing to light these di¡erent meanings.

Santiago del Estero, 1993

In many ways, Santiago del Estero symbolizes the relegation of theArgentine interior. Every single study28 locates Santiago as one of theprovinces with the highest levels of ` unsatis¢ed basic needs'' (27.4% ofhouseholds puts the province in the second place only after Jujuy),lowest income levels ($232.60 per inhabitant puts it third after Chacoand Formosa) and lowest life expectancy (69.8 years, sixth after thepoorest provinces of the northeast and the northwest). The provincehas, according to a report from the United Nations Program forDevelopment, the second worst ` index of human deprivation'' and thesecond largest percentage of children living in poor households(42.2%). As of 1994, the primary sector consisting of the agriculturaland livestock activities contributed 14% of the value added of the totalo¡er of goods and services (horticulture, cotton, soya, and surghum,and, of lesser importance, cattle raising). Industry is hardly signi¢cant(the secondary sector contributed 18% of the value added, mainly infood, beverage, and textile production). The overwhelming majority ofthe total economic activity is concentrated in the tertiary sector (¢nance,transport and communications, commerce, tourism, and mainly gov-ernment services), being the most important source of employment. AsZurita puts it,29 ``Santiago del Estero is a case of dependent develop-ment without industrialization; public and service sectors are centralin urban areas, the agricultural sector is segmented in areas devoted toexport and a huge sector of subsistence peasantry.'' Public employmentis at the center of provincial life ^ and a crucial factor in the under-standing of the riot by public employees. Close to forty-six percent ofwage earners are public sector employees; as many residents told me,` this city lives at the rhythm of public administration, if somethinghappens there, everybody feels it.''

156

The thousands of public employees and residents that converged onthe main square of Santiago on December 16 were not only trying toclaim their unpaid wages, which were some three to four months inarrears. They were also protesting against government corruption. Cor-ruption scandals involving multi-millions broke open almost every weekon the front page of the main local newspapers during 1993. Serious ir-regularities were denounced in the distribution of public housing andpublic land (mainly used as goods to be distributed before elections in ablatant illustration of what the main newspaper labeled ` political clien-telism''). The soup kitchens serving poor neighborhoods were also theobject of obscure dealings; they were closed because funds sent by thefederal government had mysteriously disappeared. More than a milliondollars had been paid for public works that were never done; hundredsof vehicles bought by the provincial state had vanished into thin air; thelocal social security system's program for the retired was in completedisarray because of money-squandering by prominent o¤cials.30 O¤-cials had their hands in the public funds partly because of the localjustice system's ine¤ciency or ^ worse, as the main newspapers oftenimplied ^ outright complicity. O¤cials were portrayed not only ascorrupt but also as greedy: They are, according to the local newspaper,` the best-paid public o¤cials in Argentina, despite the fact that theprovince is among the country's poorest.''

Corruption cases were not merely material to read about and discusswith friends in co¡ee shops and during street rallies. Adding injury toinsult, they also a¡ected everyday routines and posed serious threatsand su¡ering to many Santiaguen¬ os. Days before the riot, manylearned through the main local newspaper that top o¤cials and localpoliticians were presumably involved in the operation of a clandestinemeat market. Almost half of the meat that the city's population con-sumed was being distributed without the proper controls, posing seri-ous health risks for the local population. To make matters even worse,many areas of the city lacked potable water because government o¤-cials seemingly squandered the money budgeted to buy the chlorine totreat the water system.

This is then the context that predates the uprising: Public employeeswho for three to four months have not been paid (and in a city that` lives at the rhythm of public administration,'' the subsequent disrup-tion of everyday routines and expectancies), and widespread corrup-tion within the public administration. As Juana, a resident of Santiagoputs it: ``The whole thing was a terrible chaos.''

157

The dominant framing: The stories o¤cials and journalists tell31

That hot morning of December 16, 1993, ` the people of Santiagoexploded against corruption and backwardness. The violent demon-stration began at the Government Building.'' The detailed narrative,published by Santiago's main newspaper, entitled ` The Saddest Day,''says that ` nothing made violence likely to occur that day.'' The vio-lence of that ` fatal morning'' was sudden and took the police bysurprise, the report goes on, so much so that they lacked the necessaryammunition to carry out sustained repression of the riot.

Implying that this day's events obeyed some hidden plan, the reportasserts that protesters (identi¢ed by the newspaper as public em-ployees, professionals, unemployed people, teachers, retired elderly,students, politicians, and agitators) ` seemingly better organized thanon previous opportunities,'' began to throw bricks, stones, sticks, bot-tles, and £at paving-stones at the Government House. One of thestones, thrown by an ` unknown hand,'' hit the face of the chief ofpolice who was trying to ``dialogue with demonstrators.'' This was acrucial moment in the development of violence. When the chief, hishead covered with blood, passed out, disorder and repressive policeresponse ensued. Minutes later police agents ran out of ammunition(tear gas and rubber bullets). It was late when the infantry guardsprocured new ammunition, and the protesters were already ` the own-ers of the battle¢eld''; they were ``in charge of the situation.'' Hundredsof projectiles entered through the House's windows while policemenran from £oor to £oor ` without knowing what to do.'' Fire took hold inparts of the building. The police, lacking any means for forceful re-sponse, were totally overwhelmed. The governor refused to abandonthe building. At 11:30, the ``building was completely on ¢re,'' and thechief of police convinced the governor to leave the palace:` Governor . . . there could be a massacre here, leave the building withthe cabinet members, and we will escort you.'' Just after the governorleft, the 27 infantry guards also abandoned the scene, and ` the ¢nalsacking of the government building began.'' Forty minutes later, thereport goes on, the courthouse became the target of more than ahundred ` enraged protesters,'' who went there to vent their discontent.They broke windows and entered the building, where they stole com-puters, typewriters, and court case ¢les and burned desks and chairs.In the midst of these disturbances, opposition party members ` pro-moted (fomentar) violence.'' The action of the ` revoltosos'' was notrandom, because some tribunals were ``more vandalized'' than others

158

(Criminal Tribunal Five, for example, where many ¢les related tocorruption cases were kept).

At once, a group of furious demonstrators attacked the legislature,` destroying everything they found.'' The ` mob'' (horda) threw thelegislators' chairs out of the windows, then headed toward the home ofGovernor Lobo ` with the ¢rm intention of burning down'' his house.As the ` revoltosos'' broke into Lobo's house, a group of infantryguards arrived at the scene, preventing the assault. But the ``mob''moved faster than the police; an hour later they were sacking andburning the homes of several prominent public o¤cials and formergovernors (Cramaro, Iturre, and Juarez). Armchairs, tables, under-wear, carpets, appliances, clothing, doors, and windows were the` principal trophies of the enraged mob'' (turba enardecida). One ofthe homes that su¡ered the most devastation was that of former PublicWorks Minister Lopez Casanegra who initially tried to defend hisproperty. Another group of demonstrators headed to the house of oneof the leaders of the opposition (Zaval|a), who shot at the crowd andstopped the rioters from breaking into his house. It was 4:30 when acrowd of 250 attacked the residence of former Governor Mujica,burning both his house and car, and ` furniture and appliances werestolen'' while ``neighbors applauded and celebrated'' the destruction.This destruction ` served as a way of venting the discontent against thispolitician.'' Later that same afternoon, 200 demonstrators broke intothe homes of former legislators Gauna and Granda; the latter unsuc-cessfully tried to defend his house. As the Gendarmer|a Nacionalarrived in Santiago, the homes of a member of the Superior Tribunalde Justicia (Moreno) and the leader of the largest teachers' union(Diaz) were also destroyed and burned. That night, the headquartersof Matelsan ^ property of former Governor Iturre ^ was attacked,doors broken, and furniture destroyed while neighbors ` cheered theattackers.'' The homes of a former undersecretary of media and institu-tional relations, Brevetta Rodriguez, and legislator Riachi were alsosacked and burned. Finally, at 9:30 one of the buildings of the Ministryof Social Welfare was assaulted. An hour later, the National Senateauthorized federal intervention in Santiago del Estero. ` This is thebeginning of a new period in the history of the province'' ^ a history,the report concluded in December 1994, that ``is still being written.''

Together with this chronological report, the newspaper presented thetestimonies of six women and three men who, as spectators to thoseevents, expressed their feelings about what had happened a year earlier.

159

As expected, that ` sad day'' is remembered with sorrow. ``I felt verybad because of what was going on,'' Susana said, ` I was very worriedfor my family, mainly for my three sons. I believe that the peopleshouldn't have acted so violently and shouldn't have destroyed thepublic buildings.'' Ester stated that she was ``angry and afraid,'' Eugeniathat she ` lived the events of December 16 with pain and bitterness.'' ``Iprefer not to remember,'' said Sandra, ` because it was something reallysad,'' while Mar|a recollected the ``terror'' she felt. ``It was frightening.''December 16 is a ` bad memory'' for Gustavo, ` because it was useless.''`A sad story,'' says another public employee, ``but it was good for theprovince because the people reacted.''

It was also a sad day for Luis Lugones, the judge whose o¤ce at theCourthouse (Tribunal Five) was one of the main targets of the revolto-sos, and who was in charge of the 144 persons arrested on December16. Six years after the events, how does he remember these events?What story does he tell about December 16? In his opening statementof our two-hour talk, his interpretation of what happened that ` sadday'' mingles with an account of his actions before, during, and after-ward: ` I do not regret anything I did,'' he tells me. Why should he berepentant? He was in charge of one of the most noted corruption casesin the province: this involved the undersecretary of media and institu-tional relations (Brevetta Rodriguez) who, in connection with otherpublic o¤cials and the governor, signed a contract between the gov-ernment and a ghost publicity company for US$300,000. After twentydays as a fugitive, Brevetta Rodriguez showed up at Lugones's o¤ce butwas released the next day, a release that ^ for many local commenta-tors32 ^ was the ¢nal blow to the courthouse's public image: justice wascomplicit with entrenched powers. ``Since bail was posted (excarcel-able), and since I am a loyal defender of constitutional guarantees, Iremoved him from prison,'' Lugones told me in August 1999. ` Thepeople did not understand,'' he commented, ` because they were guidedby the media. It was the media who kept on making things moredi¤cult, who kept fanning the £ames.'' He ``did the right thing'' aphrase repeated often during our interview ^ ` with the Brevetta caseas with those arrested'' for sacking and looting politicians' homes. Injustifying his decision to liberate the Santiagazo's 144 arrestees (88men, 7 women, and 49 male minors), Lugones explained that ` theywere in danger, since the people inside the prison center had learnedthat their ¢les had been burned and were going to punish those respon-sible.'' He was ` actually protecting them,'' he insisted. Those arrestedwere ` very humble people, incapable of acting by themselves: they

160

were a herd.'' This ` innocent £ock'' was actually incited by ` agitators,''the judge didactically informed me. The ` crowd consisted of those whoprovoked, who were the ones who set everything on ¢re, and those whotook advantage of the situation'' (looters who stole a chair or a desk,some of whom were arrested by the police and later released by him).The ` agitators,'' he continued, ``were a mix of people from other prov-inces likeTucuman or Cordoba and local union leaders.'' But they werea ` tiny and isolated minority. Three hundred people are not the wholesociety . . . only ¢fty of them said ` Let's burn everything.'' They cameprepared with gasoline. These activists came with little pieces of paperindicating the houses that they were going to burn.. . . [T]here werepolitical interests behind it.''33

It is doubtful, writes historian George Rude about the rioting crowd,that ` any clear-cut distinction .. . can be made between the bulk ofthose who join the crowd and those who line the sidewalks or evenstay at home.. . . [T]here is an evident bond of sympathy and commoninterest linking the active few with the inactive many.''34 Judge Lugoneswould deeply disagree. Apart from those who ` agitated'' and those who` took advantage,'' he said, the majority of people ` watched the wholething on TV with great sorrow, because a historic monument (thegovernment building) was burned.'' Sorrow and sadness are com-manding themes in his story, chie£y when he recalls his own feelingsupon learning that the courthouse was burning: ` I felt a tremendouspain, because it was our house.''

What caused the riot? The judge and most journalists have a ready-made answer that blends the identi¢cation of a claim with the emer-gence of mobilization (a con£ation that political process theorists havelong ago proven mistaken35). According to this point of view, the riotwas caused by the three-month lag in payment of public wages ^ nothingmore, nothing less. The government stopped paying its employees forthree months, and by December they were ` mad as hell'' ^ a journalisttold me ^ and (we might add, to paraphrase the classic ¢lm Network)were ` not going to take it any more.'' Thus, another journalist put it,` fury, disenchantment, irritation, and the need to steal took over thecity. . . .'' 36 Unpaid salaries were also at the root of the lack of e¡ectivepolice response to the riot. True, the police were overwhelmed by theonslaught of protesters (the police report on the riot mentions thesheer number of demonstrators ^ their ` numeric supremacy,'' their` excited state,'' and the lack of necessary anti-mutiny ammunition asreasons for the less-than-vigorous attempt at containment) but, ``as

161

everybody in Santiago knows,'' many journalists told me, police wageswere also unpaid. This, together with the fact that many of the police-men had relatives among the protesters, explains the absence of anysustained police response on the day of the riot. The executive directorof El Liberal told me what his friend, then-Governor Fernando Lobo,privately acknowledged after the riot: ``I didn't pay the police. Thatwas my mistake.'' And, according to many, that explains the lack ofrepression and the ` freedom'' enjoyed by rioters that day.

In addition to unpaid wages (of public employees and the police),widespread corruption fed the anger, fury, and ``irritation'' that ``thepeople'' felt at that time. As one journalist explained: ` The Santiaguen¬ osgot tired of so much corruption, felony, impunity. . . . They explodedbecause they were fed up .. . with the deplorable spectacle of politicians,union leaders, and o¤cials who were sharing the booty. . . .'' 37 As anotherjournalist from El Liberal put it, government corruption was one of the` driving forces behind the protest.''38 Much like the judge, many journal-ists who reported on these events created a taxonomy of participants ^distinguishing protesters from ` vandals'' ^ and highlighted the presenceof agitators: `A lot of strange faces, some of them with accents from [theprovinces of] Buenos Aires, Tucuman, Cordoba.. .''39; and ` among the1,200 people who went to the demonstration of public employees, only100 at the vanguard assaulted and burned .. . .'' 40

An innocent crowd led by activists ^ a ` passive instrument of outsideagents,'' as George Rude41 would put it ^ vented their anger at theirunpaid salaries, the judge explains; and at the generalized corruption,most of the journalists add. They agree with the executive director of ElLiberal who puts it very clearly when he writes: ` To a great extent, itwas the work of at most 300 activists, and a similar number who, atleast in the beginning, escorted them with cheers and gestures of sup-port.''42 Local politicians whose homes were or were not burned alsocredited outside organizers ^ that ` mythic culprit blamed so regularlywhen `innocent masses' rebel all over the world''43 ^ for ` acts ofvandalism.'' With these nuances and the internal contradictions thatare beyond the scope of this article, those occupying dominant posi-tions in the local political and journalistic ¢elds construct a ` dominantframing''44 ^ i.e., an interpretive scheme that simpli¢es and condensesthe many di¡erent dimensions and meanings of the riot ^ to explainthe events of December 16, 1993. As we will see, it is against the back-ground of this framing (or better, in dialogue with it) that protestersconstruct partially di¡erent stories about the same events, although

162

they are always ` constrained by the hegemonic talk of the powerhold-ers.''45 This dominant framing has, for its defenders, ` the force offacts'' behind it. After all, Governor Juarez was elected for the fourth(and in 1999 for the ¢fth) time by ` the same people'' who burned downhis house. ` See, nothing changed,'' I was repeatedly told.

According to this discursive construction of December 16, since noth-ing much has changed in Santiago del Estero, nothing much actuallyhappened that day: it was a ` mere wage claim.'' As Judge Lugonesexplains, for those who ` stole a chair or a TV set, what happened onDecember 16 meant nothing, nothing at all, maybe a couple of bottlesof wine to drink, that's all.'' The ` so-called Santiagazo did not exist. Itdidn't change the destiny of Santiago del Estero.'' He interprets Decem-ber 16 as a non-event, not as that ` historical fact that leaves a uniqueand singular trace, one that marks history by its particular and inimit-able consequences'' ^ as Olivier Dumoulins de¢nes an event46 ^ but asa ``peak of fever, as a couple of more degrees in the heat of Santiago.After that, everything went back to normal.''

The ¢red cop gets his chance to talk

` That day cost me my career,'' Mario, a police chief in charge ofsecurity for the government building on December 16, told me afterintroducing himself. For him, nothing went back to normal. Withinmonths, he had been ¢red from the police force over a series of epi-sodes related to the burning and sacking of public buildings and pri-vate homes. Now unemployed but still very angry with ` those at thetop of the institution,'' he has (¢nally?) found someone to ``set therecord straight.'' In fact, Mario called my hotel after the leading localnewspaper published an article, headlined ` The Santiagazo seen froma sociologist's point of view,'' that reported my presence in the capitalof Santiago del Estero. Over the phone he said: ``I want to tell you thewhole story, my version of what actually happened.'' We talked formore than two hours. At the end of our conversation I had the sensenot only of having gained privileged access to a private but veryrelevant version of the events ^ a story that otherwise might have beenlost ^ but also of having touched on a dimension missing from theo¤cial framing of these events. For Mario, the riot and its aftermathwere not merely about claims but also about dignity and recognition asa policeman.

163

Mario was ``studying'' all the maneuvering and coordination takingplace ``before that day.'' He was ` doing intelligence because I wasinterested in what was behind the wage claim, the motives, the peoplewho were involved.'' Implicitly knowing that interaction between actorsis the ``locus and basis of contention,''47 Mario was ` going beyond'' his` jurisdiction to identify the groups that were usually demonstrating infront of the Government House,'' and relations between them. ``Iattended union meetings and took pictures. I had very good informa-tion about the most active unions, about the coordination betweendi¡erent groups.'' He acknowledged that ``I knew something big wascoming, and that the burning of the Government House was the people'sobjective,'' however, ` the whole responsibility for what happenedrested with the police. The police did not take the situation seriously.''Even though I never mention the o¤cial version of the events, Mariomakes an explicit and spontaneous reference to what he calls ` news-paper lies.'' He asserts that what newspaper reports cite as the crucialmoment in the initiation of violence (the stone thrown at the chief ofpolice) is an ` outright lie. He (the chief) faked it, and ordered repres-sion. The people then become enraged,'' police tactics back¢red, ` andwe were the repressed.'' Many times during our interview Mario seemsto be looking straight into the eyes of the judge, journalists, and otherpolice agents to challenge their version. He openly alludes to theaccounts that see the ` riot'' as the product of foreign agitators or alien` activists,'' and points out that the ``explosion'' was the result of intensecoordination and planning carried out by protesters during the pre-vious weeks. ` Activists, yes .. . if by that you mean that some people aremore active than others, but they were all from Santiago,'' he insists.

Mario provided me with a great deal of detail about the reasons hethinks the police did not e¡ectively quell the protest: They lackedammunition ^ and what they had was of very ` bad quality'' (it datedfrom 1978), the tear gas was so old that it would not blaze allowingprotesters to ` return the gases to us.'' But mainly, he points out, it wasbecause the infantry ``received an order to abandon the place,'' and` we, the people from my precinct, were left alone.We didn't even haveclothing; our uniforms were destroyed, we were dressed as civilians.We couldn't do anything.'' He vehemently opposes the explanation thatpoints to the police's own wage claims as the reason for their inaction,and he hints, without explicitly saying so, at an underlying moraleconomy of the police force that was being threatened at the time andmight explain why they did not react in the expected way.48

164

(The wage claim) is an excuse . . . . We could have done something to protectthe House.We tried to calm people down, but we didn't have guns.We weretotally disarmed.We didn't even have proper clothing .. . . Although we didn'thave the means, we could have prevented it. I was angry at the lack ofcapacity and leadership of my superiors, not of the subalterns . . . . Politicshas always been involved in the police force, all the promotions are donethrough politics.

They ``didn't have clothing,'' he repeats throughout the interview.` They didn't have guns,'' he stresses, ``and the ammunition was old.''To make things worse, ` the superiors were appointed through politics.''For Mario, the events of December 16 were not so much about wages,but about organization (of protesters) and an already lost dignity (ofpolice agents). On that day, the lack of ammunition, clothing, andlegitimate leadership exposed the lack of recognition that they ^ the` subalterns, not the superiors'' ^ had as cops. Since they had alreadystopped being cops, they consequently did the logical thing: they leftthe scene.

Mario's dignity as an o¤cer was challenged again right after the riotwhen ` my superiors ordered me to ¢nd the things that were stolen thatday and the following day.''A ` very nice Spanish pistol . . . that was the¢rst thing Governor Juarez ordered me to recover. I got many thingsback from the sacking of his house: classic furniture, a very beautifuldesk, Nina's (the Governor's wife) fur coat, many, many things.'' Heshowed me a list of the things he found: typewriters, fans, heaters,bicycles, computers, telephones, ¢rearms, air conditioners, VCRs,clothing. During our interview he also displayed the pictures that heand his fellow o¤cers took during the sacking of the politicians' homesand that later allowed him to track down the missing items. ` It was notso di¤cult to ¢nd the stolen objects,'' he said. The problem arose whenhe found that the most valuable objects (Nina's fur coat, her goldjewelry, her expensive clothing and shoes) were in the possession ofo¤cials close to the governor. ` Juarez's bodyguard had his Spanishpistol . . . and a deputy's lover had Nina's fur coat,'' Mario told me and,seeing my surprised face, rapidly added, ``Yes, yes . . . I was playing with¢re.'' But he kept on in his search for the stolen goods. ` As a good cop,I followed orders,'' and he began receiving threats. ` People at the policeforce told me to stop because I would be ¢red.'' He did not stop, andlater that year, ` they implicated me in the theft of a cider truck, sayingthat I was going to buy all the stolen cider.'' He then opens anotherfolder, not the one with all the pictures of protesters stealing thingsfrom politicians' homes, but one with newspaper clips that report the

165

` scandal in the police force. A cop involved in a truck theft.'' Predict-ably, he was ¢red, ``¢red for playing with ¢re,'' he tells me. ` December16 was the beginning of the end of my career as a cop,'' he summarizes,` that's why I wanted to tell you my version of what happened.''

The stories protesters tell

Enraged spontaneity, dignity, and the festive atmosphere of burningand sacking are, against the dominant framing, the elements thatdirect participants in the event either explicitly thematize or implicitlyrefer to.

` Before the police left the scene, there was a brief encounter betweenthe cops and the people. You didn't know whether to bitch at them,punch them, or forgive them. The people ¢nally applauded the cops,and they left. When that happened we didn't know what to do.. .''Roberto told me. ``I began looking for the people of the Union Front,49

to tell them to take charge of things. . . . Nobody knew what to do.. . .''

Figure 2. ` Before the police left the scene, there was a brief encounter between the copsand the people.You didn't know whether to bitch at them, punch them, or forgive them.The people ¢nally applauded the cops, and they left.''

166

(see Figure 2). Against the alleged presence of agitators, this confusionconveys a sense of spontaneity of action that is explicitly emphasized inthe interviews. All my interviewees make explicit reference to what Icall the o¤cial framing to later object to parts of it: ``It wasspontaneous . . . there were no people from other places as it is said.We all knew each other. It was the mood of the people,'' a leader of theteachers' union told me. And her comrade added, ``Everything wasspontaneous . . . . we went to the courthouse, but there wasn't any or-ganization.We heard that people were going to the courthouse, so wewent there. On my way home, I stopped by the legislature while peoplewere throwing things out of the windows, I didn't see any strange facesthere. There were no activists as people say.'' Aware of competingunderstandings about the riot's driving forces, all the active partici-pants I interviewed explicitly deny the existence of agitators and resortto the metaphor of contagious anger to explain why they did what theydid: ``It was a spontaneous thing, it was an event that occurred becauseof the situation in which we were living,'' says Juana, who at that time,was an organizer in a Catholic Base Community. Or as Nana put it,showing familiarity with the dominant narrative, ` Some say that it wasjust the work of vandals. Maybe there actually were some vandals hereor there, but those who initiated everything, those who broke thepolicemen's blockade were not vandals but workers. They were work-ing people.We did not hire any barra brava (gang) to break the police-men's blockade. We did that ourselves. We formed circles and startedjumping and threw ourselves against the cops, turning and whirling,like kids do in the clubs, so that we could break it . . . so that we didn'thave to go on facing them.'' In point of fact, Nana and the rest high-light the lack of organization as a major problem of the riot.

While the ` fever'' referred to by the judge serves the purpose of convey-ing a certain irrationality of the crowd and the innocent character ofthe ``horde,'' the contagion and spontaneity that protesters talk aboutful¢lls another function. Similar to the North American black stu-dents'' sit-ins analyzed by Polletta, the repeated reference to (andexplicit emphasis on) spontaneity o¡ers protesters ` some defenseagainst the charges that the demonstrations were led by `outside agi-tators.' ''50 Acknowledging but at the same time contesting the o¤cialversion of the events, Nana asserts,

This was something done by Santiaguen¬ os from Santiago del Estero; therewere no groups of rabid fans (soccer gangs) of any club here. This is whatpisses me o¡ the most about the Santiagazo; people say it was organized by thisone or that one. I think that if there had been anybody trying to put this

167

together, it went out of his or her hands. Totally, totally, totally! I wish I couldgive you a whole list of people. . . . They would all say the same. People like mewho have no interests and no reasons to risk their heads. To risk it like mycomrades, because the bullets were coming for any of us.

While they insist on the spontaneous character of the revolt, Roberto,Maria, and Rene all acknowledge the fact that ^ as Mario, the cop,knew so well ^ there were incessant organizing e¡orts before Decem-ber 16. In fact, when asked about the riot's origins, all the protesterslocate this day in a longer series of events: ``It all began at the begin-ning of 1993.'' Their organizing e¡orts included the formation of a` Union Front'' that brought together several unions and an almost-weekly participation in rallies, marches, demonstrations, sit-ins, andteach-ins throughout the year. In these contentious gatherings (thatgrew from two demonstrations in January 1993 to thirty in September1993 to twenty-eight during the ¢rst two weeks of December 1993),protesters not only met each other in the street and realized that ``I wasnot alone, it was incredible'' ^ as Nana says ^ but they also learned todeal with mounting police response ^ ``We learned how to return thetear gas grenades to them.''51 Even a casual observer of regional eventswould note that this action was anything but spontaneous, that the` riot'' was ` bound to happen.'' Why then did the participants so fer-vently assert the spontaneous character of their mobilization? What isthe meaning of this assertion within the context of their recollections?(See Figure 3.)

Figure 3. Strikes and street demonstrations from January to the ¢rst two weeks ofDecember 1993 (Source: El Liberal).

168

Perhaps this insistence on spontaneity means something other thansudden or surprising revolt. Spontaneity, as remembered today, meansthat the protesters were both following a moral imperative to react andexpressing their decision to break with a deeply held belief in provin-cial apathy, a mythical ^ but not for that less real ^ conviction aboutthe unchanging passivity of the Santiaguen¬ os, on their submissivenessand indolence.52 As Mar|a from the teachers' union puts it, ``I like whatwe did. If we hadn't done it, we would have been unworthy. Despite thefact that it was only an explosion.'' On one hand, in asserting localinitiative, spontaneity denotes a challenge to the o¤cial framing ofthese events that locates agitators as the driving force behind the` popular fury.'' On the other hand, in asserting the worthiness of theiraction, spontaneity expresses an e¡ort to realize a moral vision, as JimJasper would put it, a vision that transcends while encompassing thematerial claim.53 Here is how Nana explains her actions: ``[I did it]because I wanted to complain, because I didn't think what was goingon was fair.Yes, what people say is true, you wanted to be paid, but youalso wanted to end the disgusting government that we had. To ¢nishsomehow with feeding so much corruption.''

It was spontaneous because it was not merely a wage claim: it was alsoa moral protest, direct action against those they felt were doing wrong.` It was like a punishment. I got back home, and I felt proud aboutwhat had happened. I thought we had just given a punishment,'' Nanatold me. For her, it was not merely about wages, it had (and still has, aswe see later) a larger meaning: it was about justice and about respect.

That night, when you could still smell smoke from the burning, I was think-ing .. . .Well, we had to put so much of our hearts into it, to generate all thatmess, so that at least they talked about Santiago in the capital city. Just sothat Santiago appears once on the cover of the NewYork Times. Because weknew that too. We are the ¢rst province, the poorest, the one that is leftbehind the most, where it is so hard to educate our children, to raise themhealthy, where it is so hard to achieve a digni¢ed future . . . . A big mess had tobe made so that someone wrote about it and became interested in us. . . .

Nana is here referring to the article, ` With Fire and Fury, ArgentinePoor Make a Point,'' published by The New York Times on December18, 1993. It is clearly not possible that, on the night on December 16,she ` knew that too.'' Should we then discard this testimony (and manyothers who mix up times and events) as wrong information? This ishardly the ¢rst testimony that is not fully reliable in point of fact.Historians know that, more than telling us what people actually did,` oral sources tell us . . . what they wanted to do, what they believed they

169

were doing, and what they now think they did.''54 Oral sources haveanother kind of credibility, their importance rests no so much in its` adherence to fact, but rather in its departure from it, as imagination,symbolism, and desire emerge.''55 This is oral source's forte ratherthan its drawback ^ ` errors, inventions, and myths lead us throughand beyond facts to their meanings.''56 Thus, this ` wrong'' tale isextremely valuable because it provides a window into the interests ofthe teller, the desires and dreams beneath those interests. Nana is tell-ing us that they want to be noticed, that they want to make it into thepages of prestigious newspapers. This mistake also illuminates one ofmemory's central features: rather than being a passive container offacts, remembering is an active process of meaning-making.57

Spontaneity then works both as a rejection of the presence of outsideagitators and as an a¤rmation of the dignity of the protesters, a dignitythat runs against the dominant framing that constructs the event as a` mere wage claim.'' As for Mario, the cop (but for entirely di¡erentreasons), for protesters the riot was about dignity, it was about stand-ing up in front of corrupt powerholders.

`At that time, we wanted to think of it as an awakening, the beginningof a new political era, a historical symbol, a before and an after. Weattributed a lot of symbolism to that event . . . but there were others,speci¢cally one journalist, who put forward the argument that this is apueblo that only gets angry when it doesn't get paid,'' Roberto admits.Like other protesters, he is very familiar with the dominant interpreta-tion of the Santiagazo; he even acknowledges some truth in the o¤cialframing, and implicitly recognizes other possible meanings besideswhat ` we wanted to think of it at that time.'' But he insists on theexistence of some larger ^ although partially unrealized ^ signi¢canceof the protest expressed in the burnings of what he and many otherscall the ` symbols of corruption.''

The dignifying dimension of the riot is something that many of theactive participants I interviewed wish to see in the events of December16, but that subsequent events (mainly the re-election of GovernorJuarez) prove uncertain. `At that time it seemed,'' Mar|a and Reneeagree, ` to be a positive moment in the history of Santiago. It was as ifthe Santiaguen¬ os were recovering their dignity, their capacity to pro-test. That was a positive thing .. . . The Santiagazo was also a lesson forlocal politicians. The Santiaguen¬ o can put up with many things for along time. But everything has a limit, and the Santiaguen¬ o is capable of

170

reacting. In one way or another that [capacity] is there. ``You [politi-cians] can keep on adjusting, but watch out because there has been aSantiagazo, and it can happen again,''' In other words, the dignity, themoral dimension expressed on that day is a sort of potential that, assuch, has opened the Santiagazo to interpretation and re-interpretation.No one puts it better than Nana when she says, ``For me, the Santiagazois an un¢nished symphony.'' The Santiagazo is a project, one that goesbeyond the pursuit of material self-interest and points at the realization ofa di¡erent political culture: ``We saw it as something healthy, as a sort ofliberation from a deeply internalized fear. It was a fresh air, a wind ofhope,'' Renee concludes. Much like the newspaper report, but again fordi¡erent reasons, the history of December 16, for many protesters, ``isstill being written.'' The members of Memoria y Participacion, thepolitical party founded after December 16, put it very clearly in a docu-ment published on the second anniversary of the event. Acknowledging,like other protesters, competing interpretations, this document sees inthe reshaping of the local political culture the main ``lesson'' of theupheaval: ` Whether or not it was a popular rebellion, whether or notsomething happened in Santiago after December 16, these are openquestions; the event is not yet closed and the answers [to those ques-tions] depend on our current and future actions.'' For them the riot isstill in the making ^ another ``un¢nished symphony'' ^ and they havetheir own version to put forward. It says the day's main aim was to``purify democracy, burn down a perverted power and rea¤rm thedignity of a people that was fed up.''

The ` fresh air'' or ` purifying ¢re'' was nowhere better expressed thanin the festive nature that the riot had for many protesters. True, mostlyanger and resentment ¢gure in protesters' accounts. But the ethno-graphic interview allows the emergence of other perceptions and emo-tions. In contrast to the o¤cially constructed ` sadness and sorrow,''many participants note the fun they had: ` It was truly hilarious,''Roberto and Nana agree.

``Give us the fat man back!'': The riot as feast

` There are many interesting anecdotes.We laughed a lot. Do you wantme to tell you those stories?'' Roberto laughingly asked me. Whatfollowed was a series of tales that contradict the sadness and sorrowthat dominate the o¤cial framing of the event: ``We laughed like crazy.It was hilarious.''

171

The main streets of Santiago became the stage for an unforgettablecollective performance. ` For once, Santiago was ours,'' Nana tells me.And Marcelo, at that time an aspiring journalist, recalls the festiveatmosphere of the sacking:

[T]here are many people who went there as spectators.When we were in theterrace it was something happy, funny. People were sitting in the terrace withsunshades because it was really hot. They were watching what was going on.And they said to each other ` Look at that one, how he leaves with thesuitcase,'' or ` That one .. . with the piggy.'' They took out chairs, doors,suitcases with clothes in them.. . .

Participants, however, do not draw the dividing line between sorrowfulspectators and angry agitators that is traced in o¤cial memory. Intheir recollections, the observable spectacle mingles with the experien-tial feast. There is both a ` bond of sympathy'' between those whojoined the crowd and those who lined the sidewalks or sat in front of aTV set, as well as a constant exchange between the roles of spectatorand active participant. As Renee puts it,

At around 3 pm, we saw on T.V. that the politicians' houses were still beingburned. And both the T.V. and radio were transmitting as if it were a soccergame. ``Now they are going to the house of such and such'' [laughter]. Andthen, on the T.V. we managed to see that they were burning (Governor)Juarez's house. And you could see spectators who looked satis¢ed at thescene. I was with my aunts. I put them in the Citroen I had then, and I wentthere to see. Half a block from the house, people from this downtown areahad clustered in their cars to see what was being done.. . . People werecelebrating . . . . Me, too [laughter] . . . of course . . . [because] they were de-stroying us. . . .

And Maria adds, ``We saw it like a popular spectacle, a thing of thepeople, really spontaneous and comprehensible.'' In an interview withManuel, another active participant, I mentioned the newspaper reportentitled ` The Saddest Day'' and he responded: ` No, not at all. It was aday of happiness and explosion .. . a lot of anger.. . . It was a sad day forthem, because the government palace and the legislature were burn-ing.'' The sad and sorrowful riot of the o¤cial version is rememberedby participants as a pleasurable and amusing experience.

At Casanegra's58 house, the upstairs bedroom's windows had bars, and thekids had already looted everything. They had started to burn it, and youcould see the £ames going up. There were some kids left upstairs who werenot going to be able to leave through the windows because of the bars. Youcould see them staying there, looking through [laughter]. And there was acrowd outside, all of them worried to see when the kids were going to get out.

172

A woman raised her hand holding a beautiful pink shoe in it. Through thebars you could see a guy who knew her and was throwing her some stu¡. Sheshows him the shoe and says ` [I need] the other one!!'' [laughter]. That guywas risking his life, and she was asking for the other shoe. How wonderful!We were laughing like crazy (Roberto).

I stayed at the Courthouse and then headed back to the Government House.I enjoyed the moment walking through the streets. We looked and walkedaround the courthouse. . . . We were celebrating, calm .. . . I never smoked ajoint, but I think it was something similar to that. . . . Yeah, because weenjoyed it, like sitting down to smoke a cigarette and drink co¡ee with agood friend ... . We were sitting down, enjoying all that, feeling the heat ofwhat was burning at the Government House (Nana).

Newspaper reports mention in passing the applause and cheers of by-standers. In protestors' recollections, the ` celebration'' takes centerstage. A cluster of images points to a carnivalesque dimension presentthat day: images of parody, degradation, and open-air cursing. One ofthe most-often-recounted images is a man sitting in the governor'schair, his arms open, saluting at the crowd from the balcony of thegovernment building. ` That really impressed me,'' Renee tells me;` that is the image that impressed me the most,'' Juana recalls. Down-stairs people sprayed the walls with curses and threats to establishedauthorities: ``X traitor. We'll kill you''; ``God forgive me. Archbishopyou are a son of a bitch''; ` Juarez, Iturre, Lobo, Mugica, hijos de puta.''Episodes of ritual de¢lement are also recalled as comical: ` This guypeed all over Juarez's and Nina's bed .. . spread all over .. . so funny.''Adegradation that lingers: `Can you imagine how nice it is to shit inNina's toilet?'' an old man told me at the end of our conversation (seeFigure 4.)

During this festive trashing, participants highlight the £eeting confor-mation of a community of demonstrators. ``One thing that caught myattention,'' Roberto recalls, ``was that there were no ¢ghts among thepeople who were sacking those houses. Each person took something,and no one bothered him.'' It was not a Hobbessian ``war of all againstall,'' because, as Gustavo ^ at that time a journalist ^ recollects, ` no-body even touched what someone else was stealing.'' For him, the` riot'' was ``a party, a catharsis, and a revenge.'' The transient com-munity that formed among protesters transformed ¢ght and punish-ment into festive action, and, for one day, it turned the world of localhierarchies upside down:

173

We saw a huge fat man coming ^ very impressive ^ with a sofa, a jewel. Itmust have been a unique piece, a beauty. The fat man was carrying it all byhimself walking through the middle of the street, like the owner in his ownhouse. And all of a sudden he turns around and sees a police car, ¢lled withpolicemen from the infantry. It stopped, and it was obvious that they had toput him in jail; the fat man could not deny he was stealing [laughter]. So thepolicemen surround him, make him put the sofa down and make him sit. Thefat man didn't really resist them. He used the whole back seat of the car and

Figure 4. ` . . . that is the image that impressed me the most.''

174

sat down with his back facing the driver. And o¡ he went. When the carturned around, the people stopped it and said: ` Give us the fat man back,give us the fat man back!!'' [laughter]. You know, they did exchange him. Thecops got the fat man out of the car and took the sofa. . . . People clapped[laughter].

In participants' recollections, there are neither activists nor outsideagitators, neither sadness nor regrets. Instead, December 16 has manyelements of a carnivalesque egalitarianism. That day is remembered as` a privileged time when what oft was thought could for once be ex-pressed with relative impunity,'' a special time that Peter Burke sees ascharacteristic of popular rituals,59 retold as the ``temporary suspensionof all hierarchic distinctions and barriers,'' that Bakhtin de¢nes ascentral in the carnivalesque.60 As Renee recalls,

At Juarez's house there were people I knew, and we greeted each other whilewe watched the ¢re. And there were people who came out carrying chairs.People like us, neither activists nor Shining Path, or anything like that. Thenwith my car, we took one street to go back, and we saw a police car going inthe opposite direction, with four or ¢ve policemen in it. They honked andgreeted us. I did, too, for the ¢rst time in my life, because I usually rejectthem. I honked, and we greeted them. Like brothers, I don't know [laughter].

The stories participants tell about that day do not exactly contradictthe o¤cial version in factual terms, i.e., what they as protesters did.Expectedly, the stories add more speci¢c details about their directactions. However, in referring to its amusing character, to its parodicand grotesque forms, to the liminal moment in which a community ofequals was formed against powerholders, demonstrators' stories pointat a deeper meaning of the event, a carnivalesque dimension aboutwhich the o¤cial point of view regarding December 16 is mostly silent.

The queen of carnival: Ethnography as recognition

Doing ¢eldwork has dull moments, but it also has some precious ones.The moment Nana handed me the crystal from the GovernmentHouse's chandelier was one such moment. Going through the news-paper archives and ¢nding a photograph of her shouting during ademonstration was another memorable occurrence. ``I was reading thenewspapers from those days, and I saw a picture of you that said:`Young woman insults journalists.' You were standing sideways,'' I tellNana in one of our conversations. ``Young woman insults press peopleaggressively. . . . Yes, it is me,'' Nana answers laughingly, and explains:

175

I was shouting and bitching because I was o¡ended by the fact that thejournalists were behind the cops, because I would have liked them to standby our side, being workers, and not taking pictures for the escrache (so thatwe could be identi¢ed later).When I asked them to give me my picture, theyrefused. And the funny thing is that the guy who took my picture was thesame guy who used to take pictures of me when I was a dancer. . . . I was adancer at the carnival.

Ethnography not only has precious moments but, as any experienced¢eldworker knows and patiently waits for, it also has breakthroughs.The moment Nana told me that she had been a dancer in the CarnavalSantiaguen¬ o for many years, a whole new dimension of her story beganto emerge.

Yes, I was a dancer at the carnival . . . . I was the best . . . .Well, that's what theyused to say. That was in the time of the dictatorship, when my mind was stillyoung .. . . I was always news .. . ` the best dancer in the carnival.'' It was aprize that was established after I started performing. ``How nice the way thatgirl dances, we should have a prize,'' they said. Then they established a prizefor the best dancer of the carnival . . . . When I was 18 years old, I could goanywhere and people would always whisper when they saw me.

For participants in a publicly denied riot (` in an event that people keepon saying did not exist,'' as Nana repeatedly told me), for people livingin a forgotten province of a forgotten region (` the poorest province,the one that is left behind the most, where it is so hard to educate ourchildren, to raise them healthy, where it is so hard to achieve a digni¢edfuture''), the ethnographic interview (far from a hostile and intrusiveact of the scienti¢c gaze) is ``an opportunity to tell part of their story.''61

It is perceived as a means of communication, a way for people to insertthemselves into the public narratives in which they are not usuallyallowed to have any presence. The ethnographic encounter is thus partof the ongoing political struggle over the meaning of the riot, anoccasion on which they can recreate the joy (``It was hilarious''; ` Likesmoking a joint''), then formulate what they expected (`At that time wewanted to see it as an awakening''), evaluate its impact in their ownlives as well as in the life of the community (``I felt proud about it . . .and I think it is something positive in the history of Santiago''), maketheir voices heard in this ` still to be written'' history, or attempt to linktheir own biographies with the signi¢cance of the event, as Nana didwhen we began to talk about the relationship between ` her carnival''and December 16.

176

In the unusual exchange of communication that, if done with care, iso¡ered by the ethnographic interview, actors have ` an exceptionalopportunity .. . to testify, to make themselves heard, to transfer theirexperience from the private to the public sphere. . . .''62 They have anopportunity to gain part of the respect they sought when rioting orwhen looking for (or secretly keeping) loot. The interview does notgenerate these stories. As Abdelmalek Sayad63 puts it: ``The presenceof the `professional' investigator provides only the looked-for opportu-nity to articulate the mature product of long self-study.'' Thus, theinterview only produces conditions in which stories can emerge anddevelop, the space where Mario can attempt to reclaim his honor by` setting the record straight,''or where Nana can strive to make sense ofher life so far:

I am 36 years old and I have been eating crap for 36 years. Many times I getdepressed, and I think about this society in which everything you are isdenied. If I am a part of the Santiagazo, and you are talking to people whotell you that the Santiagazo didn't exist, it is almost like saying that Nana is afarce, that she doesn't exist. Many times I fall, I go to hell . . . . But what a¤rmsme in my 36 years of age is that you are here, and you talk to me. And that youare leaving and going to work. I do not care what you write, you will write whatyou decipher about what this thing was. I am going to be very happy, whatever itis that you write; whether it was a carnival or not, I don't care. But I am positiveI did the right thing [my emphasis].

As we saw, the interview is an opportunity to contest the o¤cialversion of an event. It is also an occasion to establish a dialogue aboutpossible misinterpretations. When I, intuiting some link between heractive participation in the riot and her former life as the queen ofcarnival, pressed forward with the implications of the carnivalesque,Nana clari¢ed which carnival we should be talking about: the carnivalas lived experience, the carnival not as a ` spectacle seen by the people''but as the world that ` they live in;''64 her carnival.

Nana: If someone writes a book saying that the Santiagazo was a carnival . . .it will hurt me. It will hurt because we are not a majority but a group ofSantiaguen¬ os who are proud of the Santiagazo. We see an un¢nished sym-phony in it . . . .

J: Why would you be mad if someone said that this is a carnival with all thegood things and the limitations that a carnival has? Why would it hurt you?

Nana: Because the Santiagazo . . . to see it as part of the carnival where youget wet or dirty, or where people do things that you don't approve of, no! Tosee it as part of the carnival I lived, in which I considered myself to be thegoddess of dance being in limbo, because I was doing what I liked. I was at

177

my best, and I enjoyed it. If I have to compare it to my carnival, that whichsweated me out and drained me of 6 kilos per night, dancing, that carnival,yes! It was not the cute girl or the nice ass that moved us. It was a beast thatwas dancing and ate everything.Yes, that carnival, yes! Because I left my soulin the carnival . . . . I left my soul in the carnival.

As a keeper of records,65 as an active and methodical listener whofosters ` an induced and accompanied self-analysis,''66 the ethnogra-pher might also play a part in the act of recognition.67 In this case, it isrecognition that some demonstrators actively seek through their story-telling. The stories are not an arti¢cial outcome of the interview inter-action, but an ` extra-ordinary discourse . . . which was already there,merely awaiting the conditions for its actualization.''68 The moralcharacter of the ethnographer's act of witnessing (that Scheper-Hughesretrieves from postmodernist attacks with her ``good enough ethno-graphy'') ¢nds, in this case, the protesters' need to keep venting theirdiscontent, to keep the memory of that day alive, and express their ownworthiness. Their recollections, furthermore, not only preserve thememory of the event; they also protect ` the teller from oblivion; thestory builds the identity of the teller and the legacy which she or heleaves for the future.''69

Thirst for recognition: this is what the stories of Nana, the Queen ofCarnival, and Mario, the Honorable Cop, have in common. Despitetheir a¤liation with opposite sides, for both, taking part in the riot wasa personal issue. Their lives have changed radically since then: Mariowas ¢red and now works part time as a private security agent, Nanastill works at the courthouse but is now a recognized militante who isroutinely invited to left-wing union meetings as an ``activist in theSantiagazo.'' Their identities are now marked by the ``purifying ¢re'' ofDecember 16. Both carry their participation as a badge of honor. Itwas a time when they did what needed to be done and an occasion onwhich, in the midst of the confusion, they did ` the right thing.'' Retell-ing their stories is part of their search for respect, recognition, anddignity; remembering that day is part of the ongoing construction oftheir identities.

Conclusions and future tasks

For nothing is absolutely dead: every meaning willsomeday have its homecoming festival.

Mikhail Bakhtin

178

This is a ¢rst attempt to reconstruct the di¡erent memories of a highlysingular riot in contemporary Argentina. Protesters' memories areneither outside of nor separated from the o¤cial narrative but indialogue with it. Although my presence and interviewing activate andamplify the dialogue, this is not a conversation I created, a juxtaposi-tion of voices produced in the act of ` writing memory,'' but an actualexchange, the traces of which are present in protesters' testimonies inthe form of explicit allusions and challenges to what ` is said,'' to what` a journalist believes,'' and ` to what some people mention.''

This article explores this ongoing process of memory contestation asone of the most important legacies of the contentious episode. I havealso sought to examine the ethnographic interview as a space wheresome displaced meanings can be recognized, and some interpretationscan be challenged. Recognition and respect are at the center of boththe protesters' recollections of that ``day of fury'' and the relationshipbetween ethnographer and subjects.

The relationship between dialogic narratives and contentious experi-ences is complex and problematic. Actors were shouting about di¡er-ent things (and future work should address in more detail the hetero-geneity and patterning of protesters' voices) and diversely experiencingthe event (as an ` awakening,'' as a ``vengeance,'' as a ``search forrespect,'' as a ` way of saying `Enough is enough,' '' and as a ` mode ofexpressing anger and need''). Even more important for this presentwork is that what protesters say they were shouting about six yearsafter the contentious happening (in stories that are permeated andconstrained by other people's versions) does not necessarily convey: a)what they were actually shouting about at that time, and b) the ways inwhich they were ``living'' those claims. In other words, oral narrativesdo not reveal behavioral patterns or consciousness in a straight orunmediated way.70 As Daniel James71 puts it in his superb analysis ofDon¬ a Maria's life story:

If oral testimony is indeed a window onto the subjective in history, thecultural, social, and ideological universe of historical actors, then it must besaid that the view it a¡ords is not a transparent one that simply re£ectsthoughts and feelings as they really were/are. At the very least the image isrefracted, the glass of the window is unclear.

In all their uncertain character, the stories actors tell after the eventspeak not only about the ongoing political construction of the riot (the` social construction of protest''), but they also speak to the protesters'

179

hopes, expectations, emotions, and beliefs. As unclear as these voicesare ^ even more so, especially since they have been obscured by theo¤cial discourse ^ they are one of the few windows into the web ofmeanings in which the protest was embedded and, thus, into ourunderstanding of the event. Protesters' stories are one of the few keysthat ^ as rusty, bent, and unpredictable as they are ^ can help us toanswer E.P. Thompson's simple but still-essential question: ` Beinghungry, what do people do? How is their behavior modi¢ed by custom,culture, and reason?''72

There have been and still are participants in this process of memorycontestation other than elites and protesters: Catholic priests, localintellectuals, and artists are the most prominent ones in Santiago.Participants' recollections are undoubtedly in£uenced and in dialoguewith other mnemonic practices (theater performances, books written,video releases, and public commemorations of that day, etc.). Since thestories people tell about ` what happened'' on December 16 are un-doubtedly shaped by them, careful attention should be paid to thework of what Fine calls ` reputational entrepreneurs'' (agents engagedin a struggle for control of the images of the episode73), as well as to theriot-related cultural objects they produce.74

Contentious conversations also unfold through time. According toOlick,75 one of the central contributions of Bakhtin's dialogical analy-sis is his focus on language's continuous addressivity and historicity.While ``all utterances take place within unique historical situations''76

^ in this case, the rhetorical dispute I just reconstructed ^ they also` contain `memory traces' of earlier usages'' ^ which, for the case athand, means that having examined the present form of this dialogue,we should now study how the memories of the Santiagazo have trans-formed over time. In other words, given collective memory's ``provi-sionality,''77 this synchronic analysis should be complemented by adiachronic examination of memory changes.

The stories protesters tell and the objects ^ the ` souvenirs'' ^ they keepmight be part of a di¡use politics of hierarchy inversion or of aninfrapolitics of ` resistance.''78 If so, further work should explore theseheterogeneous voices and objects as both cultural remains and poten-tial discursive bases of contentious politics, and the conditions underwhich they can become e¡ective collective action.79 At the very least,they ^ the stories and the souvenirs ^ provide us valuable evidenceabout the ongoing shaping and reshaping of local political culture.

180

Paraphrasing Schwartz's image of collective memory as a mirror and alamp,80 we could then say that the stories of the Santiagazo re£ect thisdialogue and illuminate current and future political activity. Furtheranalysis should explore the ways in which protesters' versions of theevent give form to the current way of doing politics to see whether ornot the Santiagazowas ` a lesson for local politicians.''

Acknowledgments

This article bene¢ted enormously from lively and helpful discussions atthe Contentious Politics Seminar at Columbia University, the Sociol-ogy Department at UCLA, and the Humanities Institute at SUNY-Stony Brook. I wish to thank all participants in these fora and, partic-ularly, the discussants of a previous version of this article: EthelBrooks, Carmenza Gallo, and Je¡rey Olick. Charles Tilly, Lo|« c Wac-quant, Naomi Rosenthal, Lucas Rubinich, ElisabethWood, AlejandroGrimson,Wayne te Brake, Howard Lune, Roy Licklider, Carol Lind-quist, Elke Zuern, Marina Farinetti, and twoTheory and Society anony-mous reviewers made pointed criticisms and suggestions. I also want tothank Carlos Zurita, Alberto Tasso, Sonia, Raul, and Raul|n Dargoltzfor their hospitality and encouragement while I was in Santiago delEstero. In Santiago, Alejandro Auat and Carlos Scrimini made criticalcontributions to my understanding of the memories of the riot. Nanaand the rest of my interviewees deserve my deepest gratitude for theirtime and patience. For their editorial assistance I am grateful to CarolLindquist and April Marshall. This research is funded by a fellowshipfrom the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation.

Notes

1. Archival research included the reading of every issue of Santiago del Estero's mainlocal newspaper (El Liberal) for the years 1993 and 1994, and selected issues of ElLiberal and El Nuevo Diario of subsequent years, as well as a content analysis ofthree major national newspapers (La Nacion, Clar|n, and Pagina12) for the yearbefore and the year after the uprising. I also read popular magazines (Noticias andGente) that published extensive reports on the events, and watched a video pro-duced by two local journalists that provides a wonderful coverage of the events insitu. I interviewed twenty Santiaguen¬ os who took active part in the riot, either inthe demonstrations and rallies in the main square that preceded the burning of theGovernment House or in the burning and sacking of public buildings or politicians'residences. I also interviewed six local journalists, two policemen who were on dutythe day of the riot, and the judge in charge of the arrested persons. I read lea£ets,

181

press communiques, police records, and court case ¢les to the extent that they wereavailable. I recruited my informants though a snowball method: after each con-versation or interview, I asked my respondent to suggest friends or acquaintanceswho might be willing to talk about the events. To ensure the representativeness ofinformants in Santiago, I interviewed people from di¡erent unions, with di¡erentlevels of participation during the months prior to the event, and with diverseitineraries during the day of the uprising. Except for the names of well-knownpublic o¤cials, all names have been changed to protect anonymity.

2. See, John Walton, ` Debt, Protest, and the State in Latin America,'' in SusanEckstein, editor, Power and Popular Protest: Latin American Social Movements(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989), 299^328; John Walton and DavidSeddon, Free Markets and Food Riots: The Politics of Global Adjustment (Cam-bridge: Blackwell, 1994).

3. The 1989 Venezuelan social upheaval, which is a parallel example that immediatelycomes to mind, was very di¡erent in terms of its duration, the extent and targets ofthe looting (mostly stores), and the death toll (o¤cially, 277 fatalities). See, FernandoCoronil and Julie Skurski, ` Dismembering and Remembering the Nation: theSemantics of Political Violence in Venezuela,'' Comparative Studies in Society andHistory 33/2 (1991): 255^287.

4. See, Alejandro Rofman, ` Destruccion de las econom|as provinciales,'' Le MondeDiplomatique-Edicion Argentina (August 2000): 4^5; Larry Sawers, The OtherArgentina (Boulder, Col.: Westview, 1996).

5. See, Philip Oxhorn, ` The Social Foundations of Latin America's Recurrent Popu-lism: Problems of Popular Sector Class Formation and Collective Action,'' Journalof Historical Sociology 11/2 (1998): 212^246; Eileen Stillwaggon, Stunted Lives,Stagnant Economies: Poverty, disease, and underdevelopment (New Jersey: RutgersUniversity Press, 1998); Alberto Barbeito and Ruben Lo Vuolo, La ModernizacionExcluyente (Buenos Aires: Losada, 1992).