AUGMENTING INFORMATION FOR A PROPOSED...

Transcript of AUGMENTING INFORMATION FOR A PROPOSED...

AUGMENTING INFORMATION FOR A PROPOSED TAWICH

NATIONAL MARINE CONSERVATION AREA FEASIBILITY

ASSESSMENT, JAMES BAY MARINE REGION:

CULTURAL AND BIO-ECOLOGICAL ASPECTS

Prepared for: Parks Canada,

December 2009

Katherine Scott1, Véronique Bussières

2, Sylvain Archambault

3, Wren Nasr

1, Jim

Fyles4,

Kristen Whitbeck4 and Henry Stewart

5

with

Colin Scott, Principal Investigator

1Department of Anthropology, McGill University, 855 Sherbrooke, ouest, Leacock 717. Montreal, QC

Email: [email protected]; 2Department of Geography, Planning and Environment, Concordia University, 1455 de Maisonneuve W.

Montreal, QC. Email: [email protected]; 3Société pour la nature et les parcs du Canada (SNAP Québec);

4Department of Natural Resource Science, McGill University, Montreal, QC;

5Cree Nation of Wemindji, QC.

BACKGROUND & RATIONALE

The Crees of Northern Quebec have proposed an area on the eastern side of James Bay as a

national marine conservation area (NMCA). In 1996 preliminary work to identify natural

areas of significance in the James Bay marine region was completed by Parks Canada

(Stewart et al. 1996). The area proposed coincides with one of the foremost among four

representative marine areas identified at that time (eastern James Bay). Parks Canada has

expressed an interest in pursuing this potential proposal. Early in 2009 correspondence in support

of such an initiative took place between Grand Chief Matthew Mukash of the Grand Council of

the Crees (Eeyou Istchee) and Minister of the Environment Jim Prentice.

The research that is the basis of the present report was commissioned to address certain gaps in

information for an enhanced profile of the study area, to better equip Parks Canada for decision-

making with respect to a proposed Tawich NMCA feasibility study. In return for Parks Canada

field logistics support in the form of helicopter charter, our research team agreed to complete

activities during the summer of 2009 to augment existing geological, biological and cultural

information within the study area, i.e. the proposed Tawich National Marine Conservation

Area. We built on surveys carried out in 2007 and 2008 to provide a qualitative assessment of

marine and island life not covered in the field reports of those previous seasons‟ work (see

Mulrennan et al., 2009, for an overview of the current state of knowledge for this area).

The objectives for the 2009 research specified in our contract with Parks Canada included the

following:

Survey offshore islands within the study area between July 26 and July 31, 2009, using a

chartered helicopter to more efficiently collect information;

Weather permitting, the islands to be surveyed will include Cape Hope Islands, Weston

Island, Solomon's Temple Islands, Old Factory Islands, and Pebble Island;

Using a multidisciplinary team with expertise in geology, biology and anthropology,

collect data on the geology, geomorphology, flora and fauna (terrestrial, intertidal and

near subtidal, as well as any offshore observations made) and cultural significance of

these islands and other near-shore islands, as appropriate;

Note any locations which might be of particular interest with respect to potential visitor

experiences, whether recreational or educational, for people visiting a potential national

marine conservation area in this area;

Produce reports on the information gathered, for use by Parks Canada and the Wemindji-

McGill Protected Areas Project, to supplement existing information described in the

report Tawich (Marine) Conservation Area - Eastern James Bay of the Wemindji-McGill

Protected Area Project, 2009.

Our contract calls for individual reports on information collected within the study area with

respect to:

Biology of the islands and surrounding area, including the flora and fauna of the islands,

the intertidal and near subtidal area and any relevant information as to the importance or

rarity of these features, as well as any specific recommendations for the purposes of a

potential national marine conservation area

2

The cultural significance and local use of the islands and surrounding area, including any

specific recommendations for the purposes of a potential national marine conservation

area

The geology and geomorphology of the islands and surrounding area, including the

seabed, and including any information available on the potential for hydrocarbons or

mineral resources, as well as any specific recommendations for the purposes of a potential

national marine conservation area.

Because the cultural and bio-ecological team members are either the same individuals or

have collaborated closely in the course of our survey activities in this and previous years, and

because the social and ecological dimensions of the offshore environment bear joint

presentation and analysis, the first and second bullets above are addressed in the present

report. The Wemindji Geologic Report is prepared separately by team geologists George

McCourt and Youcef Larbi.

Fieldwork Dates: July 24 - August 3, 2009.

Team Members: Sylvain Archambault, Véronique Bussières, Jim Fyles,

(in alphabetical order) Youcef Larbi, George McCourt, Wren Nasr, Colin Scott,

Katherine Scott, Henry Stewart, and Kristen Whitbeck.

Places visited: - Kaawiipinikaau Minshtikwh (Blackstone Islands)

(see maps, pp. 5, 6) - Upishtikwaayaau Minshtikw (Frenchman‟s Island)

- Akwaanaasuukimikw (Warehouse Island; also referred

to as the „Gathering‟ Island)

- The „Cabin‟ Island

- Paakumshumwaashtikw Minishtikwh (Old Factory

Islands)

- Kaa-apiskuutaanikaach (Solomon's Temple Islands)

- Yaakaau Minshtikw (Weston Island)

- Wiipichiinikw (literally, „Walrus Island‟; Cape Hope

Islands on topographical maps)

- Aanuutimitinaach (Walrus Island on topographical

maps)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful for the support of the Cree Nation of Wemindji, Parks Canada, and the Social

Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, Community-University Research

Alliances Program. Especially warm thanks are due our helicopter pilot, Jorge Malabi, who

got the job done safely under vexing constraints of weather and scheduling, and Michel Coté,

Director of Operations at Whapchiwem Helicopters, for organizing logistics. Thanks also to

our families, whose support in the field and at home makes this work possible.

3

METHODOLOGY

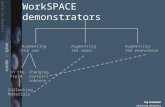

The „cultural‟ component of the present report is an overview based partly on Colin Scott‟s

research engagement in Wemindji‟s coastal and offshore area since the mid-1970s; partly on

conversations and participant observation with Cree and Inuit guides during the past three

summer field seasons (not treated in the bio-ecology-oriented field reports for 2007 and

2008); partly on Wren Nasr‟s conversations during summer of 2009 with Wemindji people

who attended the 2009 Old Factory Visit; partly on our meetings with tallymen and other

community members; and partly on published and unpublished literature.

The „bio-ecology‟ component reports on summer 2009 survey activities supported by the

present contract, with some comparative tables compiling multi-year data in the appendices.

The „ecology team‟ travelled to the islands by helicopter and boat. The achievable

destinations and the amount of time we could spend in each place were determined by

weather, as helicopter access to the islands is possible only with excellent visibility. Decisions

regarding drop-off and pick-up times were constrained by flying and safety considerations.

Time on each island was usually limited to less than four hours, but Weston Island was re-

visited because of the complexity of the habitats it presented. The majority of a day and the

following morning were spent on Old Factory Islands. Of the intended work sites, only Pebble

Island was not visited. Given unstable flying conditions during much of the period for which

the helicopter was chartered, it was deemed a dispensable priority for this year.

Our trip to Wemindji coincided with the community's annual Old Factory Visit at the

'Gathering' Island. Our base camp was set up at Old Factory (on the 'Gathering' Island) so we

were able to benefit again this year from opportunities to talk with Wemindji people about the

NMCA on a daily basis, especially when the weather did not permit flying.

Marine fauna and flora as well as avian surveys were conducted at Weston Island, Old

Factory1 and Blackstone Islands and the „Cabin‟ Island near camp. Most of the sampling for

marine flora and fauna was completed by walking along the beach or wading in the shallow

sub-tidal zone (less than 5 feet depth). At Weston and the Blackstone Islands snorkelling

using a dry-suit was also done to explore the nearshore fauna, but this was quite time

consuming. Wading was thus the more practical method since it requires little preparation

time. It became our preferred method on islands where time was limited or unpredictable.

Specimens were identified in situ when possible. Otherwise, pictures or samples were taken

for subsequent identification. Beach seining was also useful when time allowed it and beaches

were suitable (i.e., in the absence of larger boulders). This was done using a 1/16 inch mesh

size 30 X 4 feet seine net with a pouch. Specimens were identified, measured and released at

the site.

The objective of the marine and shore bird survey was to provide a qualitative assessment of

local bird populations. Therefore, bird surveys were not done in a systematic manner. Bird

observations were thus noted during the course of other activities marine sampling activities.

Similarly, our helicopter lifts, forays by freighter canoe, and walking surveys afforded a

qualitative assessment of the presence of larger fauna, both marine and terrestrial. There were

several sightings of beluga whales, from individuals to a group of eight or more. Polar bear

sightings also occurred. Abundant signs of winter caribou grazing and droppings were noted

4

on Old Factory Islands and Blackstone Islands, and caribou were sighted, solitary and in cow-

calf pairs, at Solomon‟s Temple Islands and on nearshore coastal islands, including

Frenchman‟s Island and Chiimaan Minshtikw („Ship Island‟). Signs and sounds of a pair of

wolves were present on Old Factory Islands during our visit.

Plant surveys were carried out July 21 to August 1, 2009 at Weston, Old Factory1, Blackstone,

Solomon's Temple Islands and the „Cabin‟ Island near base camp. On walks across or around

each island, we inventoried and often photographed species and habitats. Trajectories for

these walks were determined by the terrain and time available before the return of the

helicopter. Plants were identified in situ when possible or samples were taken for later

verification. Specimens that we could not identify or key in the field were pressed for later

study. The process of identification and verification is ongoing. Relative abundance of species

and environmental data were recorded. Special attention was given to intertidal and nearshore

plant communities. Due to the short timeframe for work on each island, our inventory is not

exhaustive, though it does capture a sense of the unique and varied habitats we visited on each

island and the range of species in these varied environments.

m

The team included three anthropologists, two geographers, three forest ecologists and two

geologists. There was, therefore, much discussion about various landscape processes. Some

of that material appears here. A report on the dendrochronology work done this summer on

island spruce trees and drift wood appears on Page 35. Species lists and images of habitat,

flora and fauna for each island are included in the sections below. A complete listing of

documented species may be found in Appendices 1 & 2.

1 The group of small islands at the mouth of Paakumshumwaau (the Old Factory River) and the estuary as a whole is known

in Wemindji as "Old Factory". The Old Factory Islands lie about 30 kilometers west of "Old Factory". To minimize

confusion, we will refer to these more distant islands as the "outer" Old Factory Islands.

5

Figure 1a. Location of Observation Sites for the 2009 Floral Surveys “Outer” Old Factory

Islands

Cape Hope Islands

7

CULTURAL CONTEXT AND SIGNIFICANCE

Cree Perception and Modification of Land-/Seascape

To the eye of anyone first visiting the James Bay offshore environment, it seems a largely

uninhabited natural space, classic „wilderness.‟ But for the James Bay Crees, who have

inhabited it for millennia, and for descendants of Inuit who in the 1930s made Cape Hope

Islands their home – developing ties of intermarriage and friendship with the Cree

communities of Eastmain and Wemindji – the Tawich area is a culturally resonant place.

The coastal and offshore islands, points and channels are intricately named and intimately

known. The place names indicated in Figure 1b are but a small fraction of the over 300 Cree

place names that senior hunters have mapped with Colin Scott for the Wemindji portion of the

Tawich area. These names reflect many lifetimes of experience on the land and water,

evoking narratives of events, both remote in time and more recent, that are associated with

these places, as well as textured descriptions of the places named, and the life associated with

them.

The coastal Cree people say that the land is growing. By this they mean not only that all

things in the world are manifestations of burgeoning life, but that the land is literally

emerging from the sea. They cite many forms of evidence for this phenomenon. Local people

speak of places where ancient driftwood lies on rocky slopes high above contemporary high

tide marks, well beyond the most dramatic storm events. At Solomon‟s Temple Islands, a

scattering of driftwood lies nearly at the top of the island, more than 100 feet above sea level,

suggesting that it was deposited tens of centuries ago. Placenames along the coast bear the

names of marine uses (e.g. fishnet-setting place) that have since become impossible, because

these places have become part of the foreshore. Within the living memory of older Crees,

people can point to channels where hunters used to pass in canoes, now overgrown with

willow or flooded only on exceptionally high tides; portions of the foreshore that once were

grassy that have now become part of the forest‟s edge.

On closer inspection, there are artifacts of human modification throughout the Tawich area.

Seasonal camps, current and abandoned, with hearths and tent frames or cached poles (and,

more recently, cabins) and fish-drying racks, are located on several of the offshore islands.

These are purposely discrete; they do not jump out of the landscape, for they are bases for

hunting, and signs of human presence are best kept to a minimum. Typically, fall, summer

and winter camps are separately and uniquely located, as they are adapted to the specifics of

the seasonal activities conducted there. Offshore islands on a given family‟s hunting territory

often have camps for each of these three seasons, though winter camps are always on the

mainland or on near-shore, heavily-treed islands that afford protection from the windswept

bay.

Camps have occasionally been made on islands quite distant from the mainland. During the

field season just past, we encountered two abandoned camp sites on Old Factory Islands,

which appeared not to have been inhabited for several years, but had been used recently

enough that portions of a snowmobile suspension had been left at one.

8

Hunting blinds of gathered stone or cut into dwarf conifer clumps are encountered on many

offshore islands. Low sod dikes are found on the foreshore flats of coastal bays, their purpose

to retain large ponds at which geese congregate on their migrations. For a time, these dikes

may forestall the gradually draining of these ponds, as the foreshore flats rise, eventually to be

cloaked in shrubs, then forest. Cut-ways to facilitate goose hunting, known as tuuhiikanh, are

made through the trees on forested peninsulas and on certain large, high islands.

Less visibly, there exist myriad water and ice routes for travel up and down the coast by

freighter canoe, snowmobile, paddling canoe and, in the past, dog team. Safe travel by

freighter canoe, in particular, demands knowledge of the landmarks and channels, and the

aspect of partially or wholly submerged navigational hazards in various conditions of tide and

weather. Preferred routes vary according to the strength and direction of the wind, visibility of

landmarks, etc. There are major thoroughfares known to every competent hunter in the

community, and other routes that are specific to the use of resources on particular family

hunting territories.

In cosmological terms, the Tawich area is rich in cultural imagining and practical knowledge

(Scott 1996). Tawich is a symbol of the immense power of the world, which humans must

respect. Several narratives in the categories of aatiyuuhkaan (myth) and tipaachimuun

(history, both legendary and recent) take place in coastal and offshore places (Scott 1982,

1992). Alliances of humans with marine animals figure prominently in these stories. There are

stories of humans who have visited underwater realms, where fabulous, multi-hued creatures

dwell. Features in the seascape are inhabited by ancestral spirits, vested with power and

demanding of respect. One dare not point at certain islands, for fear of provoking storms.

Significance in Cultural History

Cree interactions within the coastal and marine environment run deep historically, and have

been constantly evolving. Some 4,000 years ago, the coast was nearly 100 km inland, at Old

Factory Lake, which has yielded some of the earliest archaeological evidence of human

occupation in the Quebec subarctic, as documented by our archaeological sub-team, led by

André Costopoulos. Even three centuries ago, early in the fur trade, some portions of the coast

extended some distance inland from current high tide marks. A major 18th

century historical

archaeological site in the Poplar River area depended on coastal access no longer afforded by

receding shorelines. Frenchman‟s Island in the Old Factory River estuary, also an important

site of early European fur trade activity, would have no viable access today for a vessel larger

than a canoe. Both sites are described in David Denton‟s (2001) work. Wemindji Cree people

have been engaged in ethno-archaeological collaboration with both Denton and Costopoulos.

Perceiving the importance of the Old Factory River as a transportation route between the

coast and the interior, the Hudson‟s Bay Company set up its first trading operations on islands

in the Old Factory River estuary. It is probable that these islands were already the site of

summer gatherings, where people could support themselves with abundant fishing resources.

Such HBC trading posts throughout the region would become loci for missionary activities

and, in the 20th

century, the delivery of the first government-sponsored healthcare, education,

and other services offered to the Crees through the offices of company agents (Morantz 2002).

9

Before the move to Wemindji in 1959, the majority of the community came together to fish,

socialize and trade in the summer months on two islands located at the mouth of the Old

Factory River. Both of these islands (Kaampaanii Minshtikw, „Company Island‟ and

Taawaasuu Minshtikw, „Trader Island‟) are now effectively connected by foreshore flats to

the mainland, due to isostatic rebound, though still partly accessible on high tides by freighter

canoe. The islands still have some old wooden structures on them, and together with

Upishtikwaayaau Minshtikw („Frenchman‟s Island‟) and other islands in the vicinity that

served warehousing functions, add to the historical and archaeological interest of the area.

The birth and burial places of many Wemindji people and their ancestors are located at Old

Factory.

The cultural and historical importance of the Old Factory estuary and the larger watershed has

become the focal point, each summer, of Wemindji‟s Old Factory Visit or annual cultural

„Gathering.‟ The Gathering site is on Akwaanaasuukimikw („Warehouse Island‟) next to

Frenchman‟s Island; the latter has yielded some of the earliest historical archaeology, having

intriguing resonance with Cree oral historical accounts (Denton 2001). During the annual

celebrations, participants welcome the arrival of the annual Youth Canoe Expedition, which

finishes at the „Gathering‟ Island. The canoe expedition retraces the steps of families who

traveled between the interior and the coast along the Old Factory River in their seasonal round

of hunting, fishing, trapping, trading and socializing as a community. A related event

commemorates the settlement relocation at the end of the 1950s by recreating the journey

from Old Factory to Wemindji, using paddling canoes rigged with makeshift sails. These

community events are occasions for people to reconnect with the past and teach traditional

skills to youth, in the tradition of learning by doing, while reinforcing community and cultural

identity.

Cree Use of Coastal and Marine Resources

The use of marine resources by Cree hunters is continuous, its patterns shifting over time

according to availability of resources and changes in the needed resources. Contemporary and

historical resource use of the coastal area by Wemindji hunters is detailed in a confidential

report prepared for purposes of the offshore negotiations of the Grand Council of the Crees

with the Government of Canada by Kreg Ettenger (2002), based in part on interviews with

senior Cree hunters, and also on extensive archival notes compiled by Toby Morantz (2000).

Other sources of information about contemporary uses of resources, terrestrial and offshore,

include the James Bay and Northern Quebec Native Harvesting Research Committee (1982)

and a report by Scott and Feit (1992).

Sea run whitefish and speckled trout are the staples of the summer subsistence fishery.

Fishing has long been, and remains, the principal summer subsistence activity, at a time of

year when other animals hunted and trapped during the fall, winter and spring are mainly left

alone to bear and rear their young. But coastal fishing occurs in all seasons, including winter

fishing through the ice with jigging apparatus, and nets set under the ice. When dog teams had

to be sustained, cod were also fished, but are rarely targeted nowadays.

During fall and spring, until very recent years, the majority of waterfowl hunting during the

migrations was conducted in the coastal corridor. The offshore islands are particularly

10

important during the fall hunt, when geese staging in coastal bays, and on some of the larger

islands, set up diurnal feeding and resting patterns, transiting back and forth between the

mainland and the islands, and shifting between berries on the islands and eel grass in the

shallower waters of the bay, according to circumstances of wind and tide. During the spring

hunt, geese are more confined to the coastal bays, because most of the offshore remains

locked in snow and ice during the bulk of the migration.

In the past quarter century, there has been a shifting of Canada goose migration to inland

routes, for which Cree hunters cite a variety of reasons: the chain of vast reservoirs created by

the James Bay hydro-electric projects has altered options available to the geese; eel grass beds

have suffered dramatic declines; berry crops on the islands have been poor, in association

with a trend to hotter, drier summers; and geese have reacted also to the concentrations of

hunting effort and human presence along the coast by shifting inland.

The coastal corridor remains, however, an economically and culturally important waterfowl

area. In addition to Canada geese and Snow geese, Red-throated loons are hunted in the late

spring, and Brant geese in the late fall. Several productive duck marshes exist in the coastal

bays, and seaward, eiders, common loons, and other marine fowl are also taken. In years past,

eggs of terns, eiders, geese and gulls were gathered on the offshore islands, a practice that has

more recently declined in economic importance.

Seals for human food, dog food and sealskin for clothing have long been hunted in the late

fall by coastal Crees, both by canoe and from the seaward ice edge, though this practice too

has declined in economic importance. Younger Crees mostly do not have a palate for seal

meat (many „inlanders‟ never did); sled dogs have been replaced by snowmobiles; and the

improved warmth of commercially-available waterproof clothing has reduced local demand

for sealskin. Beluga whales, in years past, were also taken for human nourishment and to feed

dogs, but are no longer hunted by Crees, although the family of Inuit who hunt at Cape Hope

Islands still do take belugas for themselves and relatives. Polar bears are only rarely taken by

Crees at Wemindji.

Winter is the season at which Cree hunting activity in the offshore is lightest, though

numerous coastal hunting families make use of partly over-ice routes to access their hunting

camps and areas. Trapping of foxes and owls on offshore islands was a significant winter

activity historically for coasters, and is practiced to some extent to the present day, though

depressed fur prices have had an impact. Snowshoe hares and ptarmigan, and occasionally

arctic hare, are also taken on offshore islands.

Offshore islands are also important sites for gathering a variety of other resources: berries,

firewood, drinking water, and driftwood cedar for carving – cedar is not native to the area, but

is borne by sea currents from the estuaries of large rivers at the south end of James Bay. Local

Inuit also gather mussels, sea urchins and edible seaweed – resources not generally used by

Crees.

11

Coastal and Marine Tenure and Resource Management

The leaders of seven Wemindji family hunting territories have affirmed strong interest in

inclusion of their marine areas with the proposed Tawich NMCA. From north to south these

territories are known by the trapline numbers VC-9, VC-10, VC-11, VC-12, VC-13, VC-17,

and VC-14 („VC‟ stands for Vieux Comptoir, the French name for Old Factory, which was

the trading post and summer camp gathering for the Wemindji people at the time that family

hunting territories were recognized as „registered traplines‟ by the Quebec Government in the

1940s).

Socially beneficial from the standpoint of resource stewardship and coordination of hunting,

fishing and trapping, the customary tenure system of family hunting territories regulates

different resource harvesting activities in different ways, and to differing extents (Scott 1986,

1988). Because many offshore islands (for example, Walrus Island, Blackstone Islands, Goose

Island, etc.) are important habitat for geese that stage in the various coastal bays or on the

larger offshore islands themselves, they come under the authority of a „shooting boss‟

(paasischaau uuchimaau) for each family territory. The winter „tallyman‟ (amisk uuchimaau

or „beaver boss‟) on the adjacent mainland is also the paasischaau uuchimaau for fall and

spring goose hunting, and if there is more than one hunting group on a family territory, the

authority of additional uucimaauch is recognized.

The more distant offshore islands are more rarely hunted, and are not subject to regular and

routine oversight by the hunting bosses. Due to their remoteness, such oversight has been

neither necessary nor feasible. These more distant areas are regarded as community commons,

and are understood to serve the purpose of sanctuaries where nesting waterfowl, for example,

and a diversity of other wildlife remain generally undisturbed, although occasional hunting

trips are undertaken, particularly for Canada geese. In general, the more remote offshore

islands support larger populations of nesting waterfowl than islands closer to the coast, and

are important loci of resilience in regional waterfowl numbers, given reduced migrations

along the coast.

The continuity and complementarity of land and sea are important themes in the socio-

ecological discourse of Cree hunters. In a conversation at Cape Hope Islands, at the camp of

George and Louisa Kudlu, the Cree hunter Fred Blackned commented on the elders‟ view that

every living resource in the bush has its counterpart in the sea – the black bear and the polar

bear, the beaver and the seal, and so on. The expertise of Inuit is to use more things from the

sea, while that of Crees is to use more things from the bush, but there is a broad range of

overlapping skill in the use of fish, waterfowl and other animal and plant resources. From the

early decades of the 20th

century, when active hostilities between Crees and Inuit ceased,

people from the two traditions have shared their knowledge and sometimes hunted together.

12

WESTON ISLAND, July 27 & 31, 2009

Figure 3. Weston Island: a). Freshwater ponds; many broods of ducks and geese; b.) central

Weston: low stabilised dune fields and beach ridges, bogs and small ponds; c.) bears; d.)

beach ridges; e.) SE extent of gravel ridge; f.) high (<20 m) gravel ridge forms south shore of

Weston; and wide sandy beach is sheltered from N wind; g.) plateau slopes north from ridge

with a few small ponds and many geese; h.) Leymus mollis (dune grass) and dune field.

a.

b.

d.

c.

f.

e.

g.

h.

13

General Ecosystem Description

Two short trips were made to Weston Island on separate days. A pair of polar bear cubs with

their mother (Fig. 2c) were spotted from the helicopter as our pilot sought a landing place at

the centre of Weston Island to drop off the first members of the team. We had planned to hike

across the island's narrow mid point and then turn north. Instead, we landed on the high ridge

(2f) at the southern-most edge of the island and returned another day to briefly visit the

middle and northern sectors. On his return from Weston to pick up the remaining team

members, the pilot observed a pod of “at least eight” beluga on the eastern side of Old Factory

Islands. On their way to Weston, the second half of the team was flown over the Old Factory

Islands and in the 10-15 minute ride between Old Factory Islands and Weston Island, three

individual belugas were seen in separate sightings.

We counted approximately two hundred Canada geese on the portions of Weston that we

walked or over-flew, most of them in flightless condition. (On the July 31 re-visit, we saw

larger numbers of flightless geese, as we went to north side of the island with its numerous

ponds and small lakes).

During the day of the 27th

, on a flight to refuel at Wemindji a beluga was sighted in the outer

estuary of the Poplar River. On two separate days in the previous week we had seen a beluga

going into the estuary of the Old Factory River. The Inuk hunter George Kudlu, whose camp

is at Cape Hope Islands, says they go into fresh water to shed skin. At the end of the

afternoon, on the return trip from Weston, a solitary beluga was sighted just east of Weston,

and two belugas just west of Blackstone Islands. On departure from Weston on the 31st, a

beluga was seen immediately to the east of the island. Mike Hamel (personal communication,

Cape Hope Islands, August 2009) says current estimates of beluga whale numbers in James

Bay are 8,000-16,000, and that they seem to be a discrete population. This is the fourth largest

beluga population in Canadian waters.

The southern ridge (~20 m above sea level) drops off to the wide sand beach (Fig. 2f) that

curves along the length of this face of the island. An arctic maritime heath dominated by

Dryas integrifolia, Empetrum nigrum, Shepherdia canadensis and dwarf willows (Fig. 3a)

provides sparse cover on the sandy gravel of the ridge top. Abundant fireweed and shrubby

willows stabilize the face of the ridge and prevent the sand and gravel from washing away.

Further down slope, willows and empetrum have colonized the dunes. The wide (~10 m)

white beach below (Fig. 2f), similar in many ways to the southern beach at South Twin, is

relatively empty except for the footprints of geese. Driftwood is scarce. A narrow row or two

of pale white kelp, fucus, other vegetation and debris marks the tide line.

On this island, marine fauna sampling only took place on the southern beach. The intertidal

and near subtidal area is characterised by large zones of bare sand, rocky zones covered in

vegetation and bare rocky zones. It is gently sloping down. Marine fauna encountered

included Macoma balthica, Blue mussels, Green sea urchin and Iceland Scallops (Fig. 3g; a

new addition to our cumulative list of species for the area). The presence of very abundant

juvenile (15-20mm) sculpins (Fig. 3h), along with also very abundant scuds, in the beach

14

seining samples is noteworthy as it suggests that this area is a nursery ground for this fish

species.

This southern half of the island is approximately 5 km across at its widest point. The

relatively dry plateau slopes upwards to the height of land to the east. Toward the north, the

land drops gradually to wetter ground at the island's centre. The low vegetation (Salix species,

and empetrum and Epilobium angustifolium are abundant) consists mainly of tundra species

scattered with small thickets of spruce. Ptarmigan droppings were densely distributed in

thickets of stunted white spruce.

Westward a broad dune field slopes to the shore (Fig. 2h). This is a dynamic landscape in

which the work of wind and plant colonization is evident. Most remarkable are the

symmetrical willow-capped mounds that rise 4-5' above the sand and gravel (Fig. 2h). Closer

to the shoreline, much shallower mounds of sand are topped by dead tangled of roots (Fig.

3c). Both mounds and exposed wood seem to be the result of intense wind erosion of

formerly vegetated land. Sand around the willow mounds has been worn away by the wind

while the creeping willows held their own. The exposed dead branches, also the result of

erosion processes, were covered by sand at one time (this killed the plant), which has now

been blown away again. In Figure 2h, Leymus mollis is beginning to reclaim the dunes.

At the centre of Weston, which is flat and poorly drained, bogs and ponds are the main

landscape features (Fig. 3f). The terrain around them is very wet and boggy. Menyanthes

trifoliatum, Potentilla palustris, dwarf willows and ericaceous plants thrive in the wet

sphagnum where nothing grows higher than 10” (30 cm?) tall. Taller willow shrubs are

supported wherever the land rises slightly.

The broad north end of this island, which is shaped like an hourglass, is also low lying and

wet, though it is sandy and silty rather than boggy and there are many boulders. Exposed to

wind, waves and ice, it is laced with salt and fresh water ponds. Geese and ducks inhabit the

ponds and flats surrounding them (Fig. 2a). The sparse flora at this end of the island consists

of Glaux maritima, creeping willows, and other hardy maritime species.

15

Table 1. Terrestrial Flora at Weston Island July 27 and 31, 2009

Achillea millefolium L.

Andromeda glaucophylla Link Argentina egedei (Wormsk.) Rydb. subsp.

groenlandica (Tratt.) A. Löve Artemisia campestris L. ssp. canadensis

(Michx.)

Bistorta vivipara (L.) Delarbre

Botrychium lunaria (L.) Sw.

Campanula rotundifolia L.

Castilleja septrionalis Lindl. Chamerion angustifolium (L.) Holub subsp.

angustifolium

Chamerion latifolium (L.) Holub.

Comarum palustre L.

Draba aurea Vahl ex Hornem.

Dryas integrifolia Vahl subsp. integrifolia Empetrum nigrum L. subsp. hermaphroditum

(Lange ex Hagerup) Böcher

Euphrasia frigida Pugsley Fragaria virginiana Duchesne subsp. glauca (S.

Wats.) Staudt Gentianella amarella (L.) Börner subsp. acuta

(Michx.) J. Gillett

Glaux maritima L.

Hippuris tetraphylla L. f.

Hippuris vulgaris L. Honckenya peploides (L.) Ehrh. subsp. diffusa

(Hornem.) Hultén

Juncus balticus Willd.

Juniperus communis L. var. depressa Pursh Kalmia procumbens (L.) Gift, Kron & P.F.

Stevens ex Galasso, Banfi & F. Conti

Larix laricina (Du Roi) K. Koch

Leymus mollis (Trin.) Pilger subsp. mollis

Ligusticum scoticum L. subsp. scoticum Menyanthes trifoliata L. subsp. verna (Raf.)

Gervais & Parent

Orthilia secunda (L.) House

Parnassia palustris L. subsp. neogaea (Fern.) Hultén

Petasites frigidus (L.) Fries var. sagittatus (Banks ex Pursh) Cherniawsky

Picea glauca (Moench) Voss

Pinguicula vulgaris L. subsp. vulgaris

Polygonum fowleri B.L. Robins. subsp. fowleri

Potentilla bimundorum Soják

Potentilla nivea L.

Primula egaliksensis Wormsk. ex Hornem.

Primula stricta Hornemann

Pyrola grandiflora Radius

Ranunculus cymbalaria Pursh

Rhinanthus minor L. subsp. minor Rhododendron lapponicum (L.) Wahlenb. var.

lapponicum

Ribes hirtellum Michx.

Rubus arcticus L. subsp. acaulis (Michx.) Focke

Rubus chamaemorus L.

Rumex subarcticus Lepage also ofi

Sagina nodosa (L.) Fenzl subsp. borealis Crow

Salix candida Flügge ex Willd.

Salix planifolia Pursh

Salix reticulata L. subsp. reticulata

Saxifraga aizoides L.

Saxifraga tricuspidata Rottb.

Shepherdia canadensis (L.) Nutt.

Sibbaldiopsis tridentata (Aiton) Rydb.

Spiranthes romanzoffiana Cham.

Stellaria crassifolia Ehrh.

Tanacetum bipinnatum (L.) Schultz-Bip.

Tofieldia pusilla (Michx.) Pers

Trichophorum caespitosum (L.) Hartman

Vaccinium oxycoccos L.

Vaccinium uliginosum L. Vaccinium vitis-idaea L. subsp. minus (Lodd.)

Hultén

16

Figure 3. Weston Island, from upper left: a.) arctic heath vegetation; b.) willow mounds; c.)

buried willows d.) mid island bog; e.) Saxifraga aizoides in bog; f.) numerous ponds at north

end of island; g.) Iceland Scallop shells (Chlamys islandica); and h.) juvenile sculpin.

b.

. a.

c. d.

e. f.

h. g.

17

Table 2.Marine, avian and terrestrial fauna at Weston Island July 27, 2009.

Category Common name Latin name Confidence Details

Pelagic Invertebrates

Scud Gammarus sp. High

Benthic invertebrates

Macoma Macoma balthica High

Mussels Mytilus edulis High

Green sea urchin

Stronglocentrotus droebachiensis High

Iceland Scallop Chlamys islandica Med-High

Fish Sculpin sp? Myoxocephalus sp. High Several hundred small individuals (15-20mm)

Birds Canada goose Branta canadensis High

Whimbrels Numenius phaeopus High Large flock of about 20 individuals

Common eiders Somateria mollissima Med

Mammals Polar bear Ursus maritimus High Mother & 2 cubs

Fox Vulpes sp. low Scat

18

OLD FACTORY ISLANDS, July 30 & 31, 2009

Figure 4. Old Factory Islands: a.) north beach dominated by Honkenya peploides; Ligusticum

scoticum above eastern beach; c.) north-eastern beach colonized by Rumex subarcticus; d.)

bog; e.) large pond populated with sparghanium and menyanthes.

General Ecosystem Description

Terrestrial

The largest island in the Old Factory group is approximately 5 km long. Like Weston and

South Twin it is a sandy island, low lying and windswept, with many small ponds and bogs.

Fire rings and a pile of spruce poles on its eastern extremity indicate that hunters have camped

here in the early spring (there are a few skidoo parts and remnants of old goose decoys)

though likely not in the past ten years (Fig. 5g). A spine of higher ground runs the length of

the island. Beach ridges are clearly visible on its flanks (Fig. 5e). Caribou spend some part of

e.

d.

b. a.

c.

19

the winter on these islands – signs of grazing and numerous droppings were seen on the

northeastern slope of the main island. A family of wolves has made its home here, and wolves

appear to be in perennial residence, as evidenced by an abandoned wolf den that we saw.

Fresh footprints were evidentalong extensive stretches of beach on the north side of the island

(Fig. 5c) and we heard wolf calls at dawn. The absence of flightless Canada geese, abundant

on the other islands such as Weston – and numerous remains of goose carcasses – attest to the

wolves‟ appetite and hunting skills. Cree hunters remarked that when wolves are present

geese are fewer. Roughly 30-40 Canada geese were observed on the northwestern sector of

the main island, all taking wing at human approach, and more geese were heard beyond the

ridge to the west. A dozen or so Arctic loons, singly and in pairs, were observed on large

ponds bordered by extensive cloudberry fields in the boggy northwestern sector of the main

island. Ptarmigan were sighted by two team members in the central northern sector of the

main island. Numerous rodent trails were noted adjacent to boggy areas.

The vegetation on higher ground is tundra-like, dominated by lichens, empetrum and Dryas

integrefolia and Juniperus communis. Small thickets of spruce are widely scattered across the

island. Some of the spruces are quite tall (5-7 m high). Parts of the island toward the north end

are very wet. There are numerous ponds and extensive bogs that host an interesting variety of

ericaceous plants, members of the orchid family and masses of Rubus chamaemorus. Berries

of all kinds including Rubus arcticus, Vaccinium vitis-idaea, V. uliginosum, and Empetrum

nigrum are abundant. We saw many more ripening berries here than on other islands, perhaps

because the local nesting goose population had been depressed by the wolves.

The presence of seal bones on upland portions of island suggests that they may have been

carried there by polar bears, or by scavengers at polar bear kills. Cree hunters report

occasional sightings of polar bears on Old Factory Islands.

The shoreline on the north and eastern shores is scalloped with wide coves and sandy or

cobbled beaches (north). Each beach has been colonized by a different plant. Ligusticum

scoticum surrounded one beach, behind it was a field of Chamerion angustifolium. Sibbaldia

tridentata (attended by many bees) was abundant at the edges of the sand to the south. The

next beach held only Rumex subarcticus. On the northern edge of the island we found beaches

covered entirely by Honkenya peploides (Fig. 4a.), and another, much rockier beach with a

large colony of Glaux maritima and no Honkenya.

The processes of colonization and erosion are much in evidence on this island too. On the east

side of this island the gradual process of plant colonization. Further inland, as Fig. 5b shows,

erosion has begun aided by animal activity (note the abandoned wolf den in the centre of the

photo, see also 5f for a clearer view). These patches of exposed and eroding sand covered

many acres.

Intertidal and subtidal

The intertidal and shallow subtidal zones of the north-eastern portion of this island are

generally characterised by gentle slopes and host a series of smaller to larger bays. Some of

these are mostly sandy with little vegetation, whereas others have sandy bottoms covered with

boulders and even pebbles, and generally host more vegetation and fauna (Fig. 5a). One very

20

large bay is noteworthy for having a wide shallow intertidal zone, below a series of sandy

beach ridges (Fig. 5h).

The marine vegetation in the shallow subtidal zone is dominated by kelp and Fucus bifida,

which generally grows in sheltered areas surrounding small to medium boulders (Fig.5i).

Walking north, towards the channel, other species of marine plants start appearing, consistent

with last year‟s report of very abundant and diverse marine vegetation observed while scuba

diving in the channel. Marine fauna encountered includes Periwinkle (Littorina sp.), Macoma

balthica, Soft shelled clam (Mya arenaria), Blue Mussels, Green Sea urchins, Iceland Scallop

(Chlamys islandica) as well as Iceland cockle (Clinocardium ciliatum) (Fig. 5j), a new

addition to our cumulative list of species for the area. Finally the presence of abundant

shorebirds is also noteworthy. Species identified include Rudy turnstones, Killdeers,

Semipalmated sandpipers, Semipalmated plovers, as well as large flocks (some gathering 80

individuals) of Whimbrels. Other marine birds observed include scoters, Canada geese, Red-

throated loons and common eider.

21

Figure 5. 'Outer' Old Factory Islands: a.) Rusty red fucus on the north channel; b.) dune

formation; c.) wolf tracks; d.) beach ridges; e.) beach boulders; f.) wolf den; g.) old campsite;

h.) wide beach with series of beach ridges; i.) Fucus bifida; and j.) Iceland cockle.

b.

.

d.

. e. c.

f.

a.

.

g

.

i. j. h.

b.

..

22

Table 3. Terrestrial Flora at "outer" Old Factory Islands, July 30 & 31, 2009.

Achillea millefolium L. Andromeda glaucophylla Link Argentina egedei (Wormsk.) Rydb. subsp.

groenlandica (Tratt.) A. Löve Betula glandulosa Michx. Bistorta vivipara (L.) Delarbre Botrychium lunaria (L.) Sw. Campanula rotundifolia L. Carex bigelowii Torrey ex Schwein. subsp.

bigelowii Castilleja septrionalis Lindl. Chamerion angustifolium (L.) Holub subsp.

angustifolium Chamerion latifolium (L.) Holub Comarum palustre L. Draba incana L. Drosera rotundifolia L. Dryas integrifolia Vahl subsp. integrifolia Empetrum nigrum L. subsp. hermaphroditum

(Lange ex Hagerup) Böcher Festuca rubra L. Fragaria virginiana Duchesne subsp. glauca (S.

Wats.) Staudt Glaux maritima L. Hippuris tetraphylla L. f. Hippuris vulgaris L. Honckenya peploides (L.) Ehrh. subsp. diffusa

(Hornem.) Hultén Juncus balticus Willd. Juniperus communis L. var. depressa Pursh Ligusticum scoticum L. subsp. scoticum Limosella aquatica L.

Menyanthes trifoliata L. subsp. verna (Raf.) Gervais & Parent

Pedicularis groenlandica Retz. Picea glauca (Moench) Voss Picea mariana (P. Mill.) B.S.P. Pinguicula vulgaris L. subsp. vulgaris Primula egaliksensis Wormsk. ex Hornem. Ranunculus cymbalaria Pursh Rhinanthus minor L. subsp. minor Rhododendron groenlandicum (Oeder) K.A.

Kron & W.S. Judd Rhododendron tormentosum subsp subarcticum Ribes hirtellum Michx. Rubus arcticus L. subsp. acaulis (Michx.) Focke Rubus chamaemorus L. Rumex subarcticus Lepage Saxifraga tricuspidata Rottb. Shepherdia canadensis (L.) Nutt. Sibbaldiopsis tridentata (Aiton) Rydb. Sparganium hyperboreum Laest. Spiranthes romanzoffiana Cham. Stellaria crassifolia Ehrh. Tanacetum bipinnatum (L.) Schultz-Bip. Tofieldia pusilla (Michx.) Pers Trichophorum alpinum (L.) Pers. Tripleurospermum maritimum (L.) W.D.J. Koch

ssp. maritimum Vaccinium uliginosum L. Vaccinium vitis-idaea L. subsp. minus (Lodd.)

Hultén Viola labradorica Schrank

23

Table 4. Marine, avian and terrestrial fauna at "Outer" Old Factory Islands July 30 & 31, 2009

Category Common name Latin name Confidence Details

Benthic invertebrates

Lug worm Arenicola marina High

Periwinkle Littorina sp. (saxatilis?) Med-high

Macoma Macoma balthica Med-high

Soft shelled clam Mya arenaria High

Mussels Mytilus edulis High

Green sea urchin Stronglocentrotus droebachiensis

High

Iceland cockle Clinocardium ciliatum Med-high

Iceland Scallop Chlamys islandica Med-High

Birds Scoter? Melanitta sp. ? Med

Rudy turnstone Arenaria interpres High

Canada goose Branta canadensis High

Killdeer Charadrius vociferus High

Semipalmated plover

Charadrius semipalmatus

Med

Semipalmated sandpiper

Calidris pusilla Med

Red-throated loon Gavia stellata High

Whimbrels Numenius phaeopus High Very large flock of about 80 individuals

Common eiders Somateria mollissima Med

Mammals Grey wolf Canis lupus occidentalis High 2 individuals; prints, den and howling

_ Woodland caribou Rangifer tarandus High Very abundant scat

24

"CABIN” ISLAND, July 29, 2009

Figure 6. "Cabin” Island. a.) Sandy (north eastern) point and upper beach with Leymus

mollis; Heracleum maximum, Lathyrus japonicum, Hordeum jubatum; b.) Chamerion

angustifolium higher up on the same beach; c.) beach with cobbles and boulders on the southern

side of the island d.) edge of spruce forest at the centre of the island; e.) Campanula

rotundifolia on rocky outcrops; f.) rock pool above northern beach.

a

c

d

b

e

f

25

General Ecosystem Description

Terrestrial

The 'cabin‟ island is one of many at the mouth of the Old Factory River. It is similar in many

ways to the gathering island, described last year though it is about a third smaller. The higher

ground at its centre supports a small lichen-spruce forest and thickets of tangled alders.

Balsam poplars and Sorbus decora are also present. In the understory one finds typical boreal

plants such as Linnaea borealis, Trientalis borealis and Rhododendron groenlandicum. A

long spit of sandy beach stretches out at the north east corner, while beaches to the south,

north and west are rockier. Honkenya peploides, Plantago maritima, Triglochin maritimum

are plentiful. On the eastern and northern beaches a wide swath of Leymus mollis and

Lathyrus japonicus begins at the high tide mark. On higher ground Rubus ideaeus, Rubus

arcticus, Ribes Hirtellum and Chamerion latifolium along with several grasses are found. The

exposed western side of the island is a wide rocky meadow with grasses, carex, lathyrus and

Hordeum jubatum.

Intertidal and subtidal

Most of the beaches around this small island are covered with rocks and boulders, which are

covered with sediments. Marine vegetation, comprising mostly Fucus bifida with a few other

species, generally grows in low density with some denser patches. All around the island

Periwinkles are relatively abundant and exhibit a range of colour variations, from pale grey to

brownish orange.

Table 5. Marine, avian and terrestrial fauna at "cabin" Island, July 29, 2009

Category Common name Latin name Confidence

Pelagic Invertebrates

Scud Gammarus sp. High

Mysid shrimps Mysis sp.

Benthic invertebrates

Periwinkle Littorina sp. (saxatilis?) Med-high Macoma Macoma balthica High

Mussels Mytilus edulis High

Birds Herring gull Larus argentatus High

Greater Yellowlegs Tringa melanoleuca Med

Artic tern Sterna paradisaea High

26

Table 6. Terrestrial plant species on the "cabin” island, July 29, 2009

Achillea millefolium L. Alnus viridis (Villars) DC. in Lam. & DC. subsp.

crispa (Dryand. ex Ait.) Turrill ex Ait. Anemone multifida Poir. ex Lam. var. multifida. Arctanthemum arcticum (L.) Tzvelev Arctostaphylos uva-ursi (L.) Spreng. Argentina egedei (Wormsk.) Rydb. subsp.

groenlandica (Tratt.) A. Löve

Campanula rotundifolia L. Carex aquatilis Wahlenb. var. aquatilis Carex bigelowii Torrey ex Schwein. subsp.

bigelowii Carex garberi Fern. Chamerion angustifolium (L.) Holub subsp.

angustifolium Draba incana L. Dryopteris carthusiana (Vill.) H.P. Fuchs Elymus trachycaulus (Link) Gould ex Shinners Empetrum nigrum L. subsp. hermaphroditum

(Lange ex Hagerup) Böcher Euphrasia frigida Pugsley Fragaria virginiana Duchesne subsp. glauca (S.

Wats.) Staudt

Gentianella amarella (L.) Börner subsp. acuta (Michx.) J. Gillett

Gentianopsis nesophila (Holm) Iltis Heracleum maximum Bartr. Honckenya peploides (L.) Ehrh. subsp. diffusa

(Hornem.) Hultén

Hordeum jubatum L. subsp. jubatum Iris versicolor L. Juncus balticus Willd. Juniperus communis L. var. depressa Pursh Lathyrus japonicus Willd. Leymus mollis (Trin.) Pilger subsp. Mollis Ligusticum scoticum L. subsp. Scoticum Linnaea borealis L. subsp. longiflora (Torr.)

Hultén Listera cordata (L.) R. Br. var. cordata Lycopodium complanatum L. Menyanthes trifoliata L. subsp. verna (Raf.)

Gervais & Parent Packera pauciflora (Pursh) Parnassia palustris L. subsp. neogaea (Fern.)

Hultén Picea glauca (Moench) Voss Plantago maritima L. subsp. juncoides (Lam.)

Hultén Poa eminens J.Presl Polygonum fowleri B.L. Robins. subsp. fowleri Populus balsamifera L. ssp. balsamifera Prenanthes racemosa Michx. var. racemosa Primula egaliksensis Wormsk. ex Hornem. Pyrola grandiflora Radius Ranunculus cymbalaria Pursh Rhinanthus minor L. subsp. minor Rhododendron groenlandicum (Oeder) K.A.

Kron & W.S. Judd

Ribes glandulosum Grauer Ribes hirtellum Michx. Rubus arcticus L. subsp. acaulis (Michx.) Focke Rubus idaeus L. subsp. strigosus (Michx.) Focke Salix planifolia Pursh Shepherdia canadensis (L.) Nutt. Spiranthes romanzoffiana Cham. Stellaria crassifolia Ehrh. Symphyotrichum puniceum (L.) A. Löve &

D. Löve var. puniceum Tanacetum bipinnatum (L.) Schultz-Bip. Trichophorum alpinum (L.) Pers. Trichophorum caespitosum (L.) Hartman Trientalis borealis Raf. ssp. borealis Vaccinium uliginosum L. Vaccinium vitis-idaea L. subsp. minus (Lodd.)

Hultén

27

BLACKSTONE ISLANDS, July 28, 2009.

Figure 7. Blackstone Island: a.) rock slabs dominate island north and south; b.) south –facing

cliff with sorbus and other southern species at base; c.) ancient driftwood high up on raised

beaches; d.) View from cliff of sandy beach in lower right corner; e.) sandy beach sheltered

from north winds by forest and cliff; f.) gravel raised beaches in central areas, vegetation is

mainly empetrum and salix; g.) fresh water pools.

General Ecosystem Description

This group of islands lies a few kilometres out form Blackstone Bay, north of the Old Factory

estuary and islands. We landed on the largest of the islands. It is an island of mixed habitats

Belugas

here

Rafts of mergansers, many broods of eiders

Many signs of caribou

Belugas

Broods of eiders, loons

a

.

. b

g

e

d

c

f

28

that hosts caribou as well as many geese, ducks, loons and shore birds. Upon our arrival in the

the morning, two dozen geese fled the vicinity of our landing, at first running on the ground

and appearing still flightless from the molt, but the majority eventually took flight, while one

or two geese had insufficiently developed flight feathers to be able to do so.

Two team members in observations separated by about an hour witnessed a group of three

belugas working a rip current across the mouth of a small bay on the western side of the

island; possibly the same group of whales. Later we saw a beluga in the channel between

Kaawiipinikaach (the larger island on which we landed) and Kaawiipinikaash (the smaller

island).

There were signs of winter grazing of ground mosses by a small herd of caribou, with

droppings scattered over a few thousand square meters on the western side of the island. A

small bear had left footprints in the mud of a nearly dried-out pond on an upper ridge.

The cobbled and gravelly terrain indicates the raised beaches that make up this island. Rocks

(Fig. 8a) are heavily marked with black and grey lichens. Boreal forest plant species

including Sorbus decora are found in protected places at the base of cliffs (Fig. 7e). Arctic

species are evident on the windy outer reaches of the island. Dwarf tamaracks (Fig. 8b) and

spruces shelter at the edges of rock pools. Empetrum, vacciniums and salix species (8b)

carpet the ground between beach ridges. About half way between the height of land and the

water, great quantities of very old, dry driftwood balances on the rocks (Fig. 7f). An extended

description of this driftwood is offered in the Dendrology section, page 24.

Most of the marine sampling for this island took place in a small shallow (3-4 feet deep) bay

just north of the channel between the main island and a smaller island to the south east. This

was a boulder-strewn beach with some large sloping rocks slabs on the north side. The marine

vegetation is dense and comprises a Fucus bifida forest with some large kelp and other

species including Irish moss. Marine fauna observed includes Periwinkles, Lug worms,

Macoma balthica, scuds as well as blue mussels. In the channel, Sea gooseberries

(Pleurobrachia sp.) were also observed. Several bird species were also observed, as well as

three adult beluga whales.

29

Table 7. Marine, avian and terrestrial species at Blackstone Island, July 28, 2009.

Category Common name Latin name Confidence Details

Pelagic Invertebrates

Sea gooseberry? Pleurobrachia sp. Med.

Scud Gammarus sp. High

Benthic invertebrates

Lug worm Arenicola marina High

Periwinkle Littorina sp. (saxatilis?)

Med-high

Macoma Macoma balthica High

Mussels Mytilus edulis High

Birds Greater Yellowlegs Tringa melanoleuca Med

Canada goose Branta canadensis High

Sandpiper sp. low

Black Guillemot Cepphus grylle High

Common loon Gavia immer High

Herring gull Larus argentatus High

Whimbrels Numenius phaeopus High

Common eiders Somateria mollissima Med-high Mothers with chicks

Artic tern Sterna paradisaea High

Mammals Beluga Delphinapterus leucas

High 3 adults

30

Figure 8. Blackstone Islands. From top left: a) empetrum heath on raised beaches; b) dwarf Larix

laricina beside rocks pool; c & d) sheltered cove with abundant underwater vegetation and loons,

e.) fucus 'forest'; and, f.) dense underwater vegetation.

c. d.

a. b.

e. f.

31

Table 8. Terrestrial Flora at Blackstone Island, July 28, 2009.

Andromeda glaucophylla Link Androsace septentrionalis L. subsp.

septentrionalis Arctanthemum arcticum (L.) Tzvelev Arctostaphylos uva-ursi (L.) Spreng. Argentina egedei (Wormsk.) Rydb. subsp.

groenlandica (Tratt.) A. Löve Bistorta vivipara (L.) Delarbre Chamerion angustifolium (L.) Holub subsp.

angustifolium Chamerion latifolium (L.) Holub Cornus canadensis L. subsp. canadensis Empetrum nigrum L. subsp. hermaphroditum

(Lange ex Hagerup) Böcher Fragaria virginiana Duchesne subsp. glauca (S.

Wats.) Staudt Hippuris vulgaris L. Honckenya peploides (L.) Ehrh. subsp. diffusa

(Hornem.) Hultén Huperzia selago (L.) Bernh. ex Mart. & Schrank

s.l. Kalmia procumbens (L.) Gift, Kron & P.F.

Stevens ex Galasso, Banfi & F. Conti Larix laricina (Du Roi) K. Koch Ligusticum scoticum L. subsp. scoticum Limosella aquatica L.

Lycopodium annotinum L. Menyanthes trifoliata L. subsp. verna (Raf.)

Gervais & Parent Orthilia secunda (L.) House Picea glauca (Moench) Voss Pinguicula vulgaris L. subsp. vulgaris Platanthera obtusata (Banks ex Pursh) Lindl.

subsp. obtusa Pyrola grandiflora Radius Rhododendron groenlandicum (Oeder) K.A.

Kron & W.S. Judd Rhododendron lapponicum (L.) Wahlenb. var.

lapponicum Ribes hirtellum Michx. Rubus idaeus L. subsp. strigosus (Michx.) Focke Salix arctophila Cockerell ex Heller Salix reticulata L. subsp. reticulata Salix vestita remove Saxifraga paniculata P.Mill. Saxifraga tricuspidata Rottb. Shepherdia canadensis (L.) Nutt. Silene acaulis (L.) Jacq. Sorbus decora (Sarg.) C.K. Schneider Vaccinium uliginosum L. Vaccinium vitis-idaea L. subsp. minus (Lodd.)

Hultén

32

SOLOMON'S TEMPLE ISLANDS, July 31, 2009.

Figure 9. Solomon's Temple Islands. Clockwise from top left: a.) High plateau on spine of

largest island; b.) driftwood above beach on north side; c.) lichen-cranberry-empetrum; d.)

caribou; e.) gravel bars; f.) menyanthes in rock pools and „micro‟ bogs.

General Ecosystem Description

The cluster of small islands known as Solomon's Temple lies about 35 km southwest of

Wemindji and west of Moar Bay. We stopped very briefly at the largest island on June 30th.

The largest of the group curves slightly and is about 2 km in length and a half to three quarters

a.

f.

e. d.

c.

b.

33

of a kilometer wide. Unlike outer Old Factory islands to the south, these islands are higher

and rocky, similar to the volcanic rock of Cape Hope Islands to the south and Walrus Island to

the north. Although we saw no geese, there were many fresh tracks on the beaches. We saw

one caribou, perhaps caught in spring by the melting ice and isolated from the main herd.

(Fig. 9d). As we circled the cluster of islands before landing, a polar bear could be seen

swimming the channel between the largest island and a smaller island about a kilometer away,

to the northwest.

The central spine of the island slopes, often steeply, to cobbled beaches on the north and south

sides. Much of the central ridge is bare rock. The vegetation that has taken hold is a low dry

lichen heath of Empetrum nigrum, Vaccinium vitis-idaea and V. uliginosa, empetrum and

other ericaceae brightened by patches of Chamerion latifolia (Fig. 9c). Tofieldia pulsilla and

many species of carex inhabit the edges of shallow rock pools on the rocks. Small ferns and

mosses are hidden in damp rocky areas where they find protection from the wind. Masses of

driftwood (Fig. 9b) have piled up over the years above the boulder beaches on the northern

side of the island.

Table 5. Terrestrial Flora at Solomon's Temple Island, July 31, 2009.

Andromeda glaucophylla Link

Arctanthemum arcticum (L.) Tzvelev

Arctostaphylos rubra (Rehder & Wilson) Fernald Argentina egedei (Wormsk.) Rydb. subsp.

groenlandica (Tratt.) A. Löve

Bistorta vivipara (L.) Delarbre

Carex bicolor Bellardi ex All. Carex bigelowii Torrey ex Schwein. subsp.

bigelowii

Carex gynocrates Wormsk. ex Drej.

Carex nardina Fries

Cerastium alpinum L. Chamerion angustifolium (L.) Holub subsp.

angustifolium

Chamerion latifolium (L.) Holub

Draba incana L.

Dryas integrifolia Vahl subsp. integrifolia Empetrum nigrum L. subsp. hermaphroditum

(Lange ex Hagerup) Böcher Honckenya peploides (L.) Ehrh. subsp. diffusa

(Hornem.) Hultén Huperzia selago (L.) Bernh. ex Mart. & Schrank

s.l.

Juncus albescens (Lange) Fern. Kalmia procumbens (L.) Gift, Kron & P.F. Stevens

ex Galasso, Banfi & F. Conti

Ligusticum scoticum L. subsp. scoticum Menyanthes trifoliata L. subsp. verna (Raf.)

Gervais & Parent

Minuartia groenlandica (Retz.) Ostenf.

Orthilia secunda (L.) House

Picea glauca (Moench) Voss

Picea mariana (P. Mill.) B.S.P.

Pinguicula vulgaris L. subsp. vulgaris

Plathanthera aquilonis Sheviak

Polygonum fowleri B.L. Robins. subsp. fowleri

Primula egaliksensis Wormsk. ex Hornem.

Pyrola grandiflora Radius Rhododendron groenlandicum (Oeder) K.A. Kron

& W.S. Judd Rhododendron lapponicum (L.) Wahlenb. var.

lapponicum

Rubus chamaemorus L.

Rumex subarcticus Lepage

Sagina nodosa (L.) Fenzl subsp. borealis Crow

Salix arctophila Cockerell ex Heller

Salix candida Flügge ex Willd.

Salix reticulata L. subsp. reticulata

Saxifraga paniculata P.Mill.

Saxifraga tricuspidata Rottb.

Shepherdia canadensis (L.) Nutt.

Sibbaldiopsis tridentata (Aiton) Rydb.

Silene acaulis (L.) Jacq.

Spiranthes romanzoffiana Cham.

Stellaria crassifolia Ehrh.

Tofieldia pusilla (Michx.) Pers

Trichophorum caespitosum (L.) Hartman

Vaccinium uliginosum L. Vaccinium vitis-idaea L. subsp. minus (Lodd.)

Hultén

34

Figure 10: Solomon's Temple. Clockwise from the top: a.) Solomon's Temple Islands; b.)

Vaccininum uliginosum; c.) rocky arctic maritime heath; d.) caribou; e.) Chamerion

latifolium.

c. d.

b. e.

a.

35

DENDROCHONOLOGY SURVEY (S. Archambault)

Annual tree growth-rings can be used to determine tree age, but can also, if sampled correctly

(Fig. 11a), provide a wealth of information on a variety of subjects such as ecology

(population dynamics, insect infestations, fires), climate (proxy records of past climates,

extreme weather events) or even culture (dating of artefacts or human impacts on landscapes).

While some tree-ring work has been done in the past in the mainland James Bay region, the

islands of south-eastern James Bay do not seem to have ever been surveyed for that purpose.

The current work consists of a very preliminary investigation of a range of islands spanning a

65 km gradient from the nearshore (Gathering and Frenchman Islands) to offshore islands:

Blackstone Island (7 km offshore), Solomon‟s Temple (20 km), Outer Old Factory (27 km)

and Weston Islands (60 km). Growth form, tree age, crossdating potential and ease of

sampling were all investigated. In addition, some observations on subfossil driftwood were

made.

Tree cover and tree growth form

Nearshore islands (Gathering and Frenchman Islands) where both covered by moist, white

spruce (Picea glauca) forests growing on a thick moss-lichen carpet. Trees were mostly of

normal symmetrical growth form with some large specimens reaching diameters of 30-50 cm

(DBH).

All four offshore islands visited supported, in sharp contrast, very scant tree cover. The only

sizable forest stand could be found in a central depression on Blackstone Island, the nearest of

the offshore islands. Otherwise, on all exposed sites, very small krummholz clumps (rarely

more than 5-10 m in overall diameter) of white spruce were scattered across the landscape. In

most cases a central “mother” tree (height ˂ 5 m) was surrounded by concentric circles of

smaller trees of vegetative origin (layers) (Fig. 11b, c). Solomon‟s Temple Island, an island of

volcanic rock and very thin soil, was almost devoid of krummholz clumps, less than five

being observed. Weston and Old Factory Island, two islands with thick glacial outwash

deposits of sand and pebbles, supported more abundant tree clumps although always very

widely dispersed across the landscape.

The vast majority of tree clumps are alive, but some subfossil wood of local origin can be

found on certain islands. For instance a few dead tree clumps on Blackstone Island offer the

possibility to extend the colonization history of the island back in time (Fig. 11d).

Reference chronology

Large white spruces without visible growth anomalies growing on Gathering Island will form

the basis of a reference chronology, the first step in any dendrochronological work. The

objective is to obtain a regional ring width signal reflecting common growth conditions. A

total of 11 trees (2 cores/tree) were sampled for that purpose. After sample preparation, all

rings were dated, revealing two trees established around 1850 while the majority were

established in the late 1800s. Crossdating was rather straightforward with many diagnostic

rings, either narrow (2000, 1992, 1986, 1952, 1925, 1918, 1912, 1905) or large (1975, 1955)

and growth rate was quite large (avg. 2 mm). After ring-width measurement, a standardized

chronology for Gathering Island will be developed, permitting more extensive analysis.

36

Limited sample cores were taken in some white spruce clumps on the offshore islands. Short

available time, wide dispersion of tree clumps across the landscape as well as extreme

difficulty of sampling the compact tree clumps prevented more extensive sampling. Despite

these difficulties, two clumps were sampled on each of the outer islands. Indicative of harsh

growth conditions, growth form was often stunted (Fig. 11b) and ring widths extremely

narrow, with often more than five rings per mm. Maximum tree age is about 150 years with

one specimen on Old Factory Island reaching 170 years. Cross-dating with the Gathering

Island reference chronology was possible, indicating that large scale climatic factors are

indeed operating on tree growth.

Future dendrochronological developments

Crossdating potential of living white spruces across the landscape offers good possibilities for

further dendrochronological work both on ecological or historical aspects. For instance, tree

colonization of the slowly emerging islands could be better evaluated by dating the

installation of living as well as of currently dead tree clumps (Fig. 11d). Knowledge of recent

human occupation of the territory could also benefit from dendrochronological work by

dating, for instance, old tent poles, stumps or axe marks on trees.

Subfossils of foreign origin

Abundant driftwood can be observed on many of the beaches (Fig. 9b). This driftwood of

foreign origin has been transported by surface currents from the distant shores of James Bay

and possibly Hudson Bay. Since it is of foreign origin, it cannot be crossdated with the local

reference chronology. Even if its exact origin is unknown and if it is of no use for

dendrochronological purposes, its presence on the offshore islands, often many hundreds of

meters inland, could lend itself to interesting ecological or geomorphological studies.

For instance, on Old Factory Island, many decaying logs horizontally buried under a few cm

of sandy soil can be found far above the current high tide mark. Their presence would be

impossible to detect if not for the different vegetation that is now growing on the soil surface

Fig. 11e), thanks to the good growth medium and abundant nutrients offered by the hidden

decaying wood. The importance of this exogenous nutrient input as well as its impact on the

colonization of the island would be interesting to document.

On the eastern half of Blackstone Island, an area mostly covered with rock outcrops and

cobble and boulder fields, the fate of old driftwood is entirely different. Owing to the slow

isostatic rebound, driftwood can be found landlocked more than half a kilometre inland and

over 15-20 meters above the high tide mark. Resting on boulders, often as much as a meter

above ground, the old driftwood is extremely dry and its weathering increases dramatically as

one walks towards the highest (and oldest) parts of the island (Fig. 11f). Age of this subfossil

wood could very well be hundreds of years, if not over a thousand years old. Carbon-14

dating could allow more accurate description of the emergence pattern of south eastern James

Bay islands.

37

Figure 11: Dendrochronological and subfossil work. Clockwise from the top: a) Sampling

of tree-ring core; b) Stunted white spruce krummholz, Blackstone Island; c) White spruce

clone of layering origin with central “mother” tree; d) Subfossil white spruce clump,

Blackstone Island; e) buried decaying driftwood log with empetrum nigrum cover, outer Old

Factory Island; f) highly weathered driftwood more than 15 m above high tide mark,

Blackstone Island.

e.

a.

c.

d.

b.

f.

38

VISITOR EXPERIENCE

The 'visitor experience' to these extraordinary islands will need much careful consideration by

the Crees as well by people from Parks Canada. All of these islands have long been used by

the people who live on coasts of James Bay. Except for those islands close to the mainland

which are used constantly by the Crees, the outer islands are well known locally but are not

frequented. They are neither easily accessed nor easy to visit. Local people do visit to camp,

hunt and explore, but they do so with some caution. The islands, remote as they are, serve as

sanctuaries for nesting birds. Colonies of molting geese are large in summer, as are broods of

ducks and flocks of other birds. Caribou, wolves, foxes and polar bears are also at home there.

Although rough weather and fog can make travel by boat difficult and very slow, on a calm

clear day the trip to Weston takes no more than two hours. Helicopter access is much faster

but less reliable because frequent fog and rain patches on the Bay ground travelers until skies

are completely clear. This is not a place for unprepared tourists or the faint of heart. The

remoteness of the islands, though, is the quality that will likely be most attractive to visitors.

The presence of polar bears is significant. Encounters are always a possibility. Visitor

information and warnings would not be sufficient. Therefore, any visit to the outer islands

should only occur with Cree guides. It is also clear that these are not islands for intensive use

or for large crowds of people. Very small groups, accompanied by guides could, however, be

allowed to camp on the islands. Camp sites, while not sheltered, are easy to find and boat

landings are always possible. Fast flowing drinking water is not present but there are rock

pools on many islands and small ponds on others with water that can be treated or boiled.

While driftwood is plentiful on the islands, the use of dead wood for fire by visitors would be

problematic except perhaps for emergency reasons. As explained in the dendrochronology

section, decaying logs serve as nutrient sources for island vegetation. Removing quantities of

drift wood by burning it as firewood for visitors would interrupt these essential nutrient

cycles. Furthermore, on Blackstone Island and Solomon‟s Temple Islands, for example, there

are subfossil driftwood logs that are many centuries old. Burning them would destroy the

valuable information they hold about the emergence patterns of the island. Standing dead

spruces and dead branches from clonal stands similarly hold precious ecological information

and should not be burnt.

That said, there is enormous potential for interpretative and recreational visits to the island

under the right conditions. Interpretation could focus on many phenomena that can be

observed in this environment. The emergence of islands (fossil beach ridges, for example on

Old Factory Islands and Weston), plant colonization (especially the sandy outer islands),

deforestation processes, diverse ecosystems (Blackstone, Weston, Outer Old Factory and the

islands in Old Factory Bay), dune dynamics (Weston and Outer Old Factory). The area, from

the coast to the outer islands would be of enormous interest to bird watchers (all of the

islands). Fauna is abundant (shorebirds, flightless geese, caribou, wolves, beluga whales and

polar bears). The intertidal areas are fascinating and varied on every island as well as from

island to island. Those on the outer Old Factory Islands are especially diverse and interesting

for both the abundance of flora and fauna on rocky shorelines as well as beautiful sandy white

beaches. Belugas are thriving in James Bay and they can often be spotted around the islands

– this summer we spotted many from the air as well as from the Blackstone Islands. Guided

39

eco-adventure tours might include kayaking from campsites on near shore islands that could

be supervised by Cree guides, though kayaking is not traditionally a Cree skill. Bird watching

and exploring the intertidal vegetation and fauna of coastal islands would be of interest on the

near shore islands. Italian ornithologist Paolo Utmar visited Cape Hope Islands and a nearby

portion of the coastal mainland in 1990 for four weeks in August, during which period he

recorded sighting 75 species of birds (Utmar 1990). He concluded that this is a landscape of

high value and interest for naturalists, of potential interest to birdwatchers from near and