‘Atomistic’ and ‘Systemic’ Approaches to Research on New, Technology-based Firms: A...

-

Upload

erkko-autio -

Category

Documents

-

view

217 -

download

0

Transcript of ‘Atomistic’ and ‘Systemic’ Approaches to Research on New, Technology-based Firms: A...

ABSTRACT. The dominating view of new, technology-basedfirms is that these firms are driven by a heroic entrepreneurwho pursues aggressive growth. New, technology-based firmsare expected to sooner or later develop tangible products withwhich new market niches are created and existing onespenetrated. Often the only perceived economic impact of new,technology-based firms is one delivered through rapid organicgrowth.

The argument put forward in the present article is that theconception of new, technology-based firms as growth dynamosis largely misleading and partly the result of the growth biasin the traditional research on new, technology-based firms.In the present article, ten general misconceptions and moreor less explicit assumptions of the traditional body of researchon new, technology-based firms are contested. Alternativeconceptions to replace the traditional ones are proposed. Thepolicy implications of the new conceptions are discussed.

1. Introduction

There is no doubt that new, technology-basedfirms are a phenomenon of major economic impor-tance. Some new, technology-based firms havereached phenomenal growth rates, especially inthe U.S.A. Examples of such new, technology-based firms are, for example, DEC, Hewlett-Packard, Apple Computer (Slater, 1987), and, forexample, Genentech. Also the number of new,technology-based firms has been increasing at analmost explosive rate, at least during the 1970’sand 1980’s. In the United Kingdom and inGermany, an up to 30-fold increase in the emer-gence rate of new, technology-based firms hasbeen observed (Little, 1977; Segal, Quince, and

Wicksteed and ISI, 1986). In Finland, the numberof new, technology-based firms is estimated tohave experienced a 4-fold increase since the early1980’s.

Systematic research on new, technology-basedfirms has been carried out in the U.S.A. at leastsince the early 1960’s by the research groups of,for example, Edward B. Roberts and Arnold C.Cooper (Teplitz, 1965; Thurston, 1965; Rogers,1966; Cooper, 1973; Roberts and Wainer, 1968;Roberts, 1968; Roberts, 1968; Roberts, 1990;Roberts, 1991; Cooper, 1970; Cooper, 1972;Cooper, 1971; Cooper, 1973; Forseth, 1965). Themain focus of these studies has been on, forexample, the founding process of new, technology-based firms, the motivational characteristics of thehigh technology entrepreneur, on the financing ofnew, technology-based firms, and on the environ-ments in which new, technology-based firmsemerge. Typical for most of these studies has beenthat new, technology-based firms have beentreated atomistically. This means that the techno-logical environment of a new, technology-basedfirm has not been given a sufficient consideration.Such an approach tends to shift the focus on thegrowth dynamics of new, technology-based firms.

In Europe, research on new, technology-basedfirms has been carried out at least since the early1970’s (Watkins, 1973; Anon, 1969; Freeman,1971; Gibbons and Watkins, 1970; Dickenson andWatkins, 1971; Dougier, 1971). The researchtradition in Europe has largely followed theexamples set by research groups in the U.S.A.National surveys have been conducted in mostEuropean countries in the 1970’s and 1980’s(Little, 1977; Segal, Quince, and Wicksteed andISI, 1986; Olofsson and Wahlbin, 1986; Olofssonand Wahlbin, 1984; Dôutriaux and Peterman,

‘Atomistic’ and ‘Systemic’ Approaches to Research on New, Technology-based Firms: A Literature Study

Erkko Autio

Small Business Economics 9: 195–209, 1997. 1997 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in the Netherlands.

Final version accepted on April 20, 1995

Helsinki University of Technology, Institute of Industrial Management, Otakaari 1 F, FIN-02150 Espoo, Finland

1982). The first national survey of new, tech-nology-based firms in Finland was carried out asrecently as 1988 (Autio et al., 1989).

Since the pioneering studies in the U.S.A. andin Europe, the attention attached on new, tech-nology-based firms can be characterized asmassive. New, technology-based firms have beenthe focus of an impressive body of research andof a large number of policy measures. Policymakers have viewed new, technology-based firmsas a key element with which to catalyze economicgrowth and strengthen and broaden regional andnational industrial bases. A broad range of policymeasures has been devised with the aim ofalleviating barriers to growth in new, technology-based firms. This policy making process has beenfed by a continuous stream of empirical researchfocusing on factors affecting the growth of new,technology-based firms.

It is understandable that a large fraction of theexisting research on new, technology-based firmshas focused on the growth dynamics of thesefirms. If growth occurs, it can be tremendous.Consequently, many of the studies have beenmotivated by the desire to help identify firms witha potential for rapid growth and correspondingincrease in asset value. Potential high growth firmshave always provided an attractive focus forventure capitalists and regional policymakers.

Recently, empirical studies have revealed thatnew, technology-based firms may not be asaggressively growth oriented as expected (Oakey,1993). The median size of new, technology-basedfirms has been found to be approximately 10–20employees, and the mean size less than 50employees, independent of the environment inwhich the study has been conducted, even thoughthe average firm size may vary from country tocountry and from study to study (Gould andKeeble, 1984; Oakey, 1984; Keeble and Kelly,1986; Rodenberger and McCray, 1981; Dôutriauxand Peterman, 1982; Tyebjee and Bruno, 1982;Autio et al., 1989; Oakey et al., 1988). Somestudies indicate that over 60% of new, technology-based firms do not perceive rapid or even moder-ately rapid organic growth as a feasible way todevelop their activities (Kauranen et al., 1990, pp.44–45). Even more modest growth aspirationshave been cited for small information technologyfirms (Kellock, 1992; Courtney and Leeming,

1994). Westhead reports that approximately 4% ofall new, technology-based firms create as muchas 30–40% of the total gross employment in thesefirms (Westhead, 1994). In Finland, a nationalsurvey focusing specifically on high-potential new,technology-based firms, selected regionally byexpert panels, reported relatively low means ofexpected growth rates (Lumme, 1994). Focusingon small firms in general, Storey has emphasizedthe need ‘pick the winners’ and to focus policymeasures on those rare examples of high growthsmall and medium sized firms (Storey et al., 1987,p. 152).

In spite of the extensive empirical data pointingto the conclusion that most new, technology-basedfirms do not grow and do not even want to grow,the dominating view of new, technology-basedfirms even today is one presuming rapid growth,or at least an aspiration towards it. This is largelytrue both among researchers as well as amongpolicymakers. The conceptions concerning thegrowth dynamics of new, technology-based firmsare still largely simplistic, arguably to a degree inwhich the ‘true’ nature of new, technology-basedfirms is not even realized. The general simplisticand mechanistic misconceptions of the growthdynamics of new, technology-based firms are oftenreflected, either explicitly or implicitly, in thesettings of many studies as well as in the policymeasures designed on the basis of such studies.Many books and studies, while acknowledgingthat most new, technology-based firms do notgrow, still explicitly focus on rapid growth andlargely dismiss the study of slowly growing new,technology-based firms (Slatter, 1992; Poza, 1989;Riggs, 1983; Flamholtz, 1990; Barber et al., 1990;Hull and Hjern, 1989). Even though empiricalstudies indicate that the conception concerningaggressive growth orientation of new, technology-based firms is largely a bubble, arguably fed andmaintained by the growth myopia in research onnew, technology-based firms, the general miscon-ceptions and their misleading implications remainlargely unchallenged.

The present article contends that many con-ceptions produced by the existing growth myopiain the research on new, technology-based firms goagainst the true nature of most new, technology-based firms. In the present article, ten generallyheld conceptions are discussed. Alternative

196 Erkko Autio

conceptions are proposed. The research and policyimplications of the alternative conceptions arediscussed. Explorations toward the ‘true’ nature ofnew, technology-based firms are undertaken.

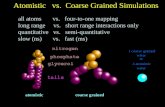

2. Atomistic and systemic approaches to research on new, technology-based firms

The main contention of the present article is thatthe general conception of new, technology-basedfirms may be mistakenly biased toward highgrowth or at least toward an aspiration of it. Thisbias is the result from the largely atomisticresearch approach employed in the traditionalresearch on new, technology-based firms.Traditionally, new, technology-based firms havebeen analyzed in relative isolation from theirsystemic environment. The traditional approach toresearch on new, technology-based firms also hasanalyzed these firms against the framework ofrelatively stable and well defined markets andindustries. Even the concept of an industry,defined as consisting of firms which are in com-petition between each other (Boyer, 1984), isessentially based on the definition of a market.Competition is assumed to take place in a marketenvironment.

The market myopia in the existing researchtradition on new, technology-based firms isexpressed in the research setting of most studiesof new, technology-based firms. First, there is amarket. New, technology-based firms emerge toserve this market. The firms may co-operate andcompete between each other, but the patterns ofthis co-operation and competition are essentiallyviewed to be dictated by the market environmentin which the firms operate.

The alternative, systemic view, put forward inthe present article, takes another view of new,technology-based firms. In the systemic view,there is first a technology base. New, technology-based firms emerge to exploit this technology basein order to make profit. Instead of a market, it ismore convenient to view the environment asconsisting of a set of potential customers, whichmay originate from a broad range of industries andmarket environments. New, technology-basedfirms strive to exploit their technology base inorder to achieve the highest value added possiblein view of present and potential customers. The

predominant way to achieve protection from com-petition is through customer specialization, notthrough low price. In order to achieve a highdegree of customer specialization, new, tech-nology-based firms often enter into a close, inter-active relationship with their set of customers.

The traditional approach to research on new,technology-based firms is largely rooted in theneoclassical economic paradigm. This paradigmhas essentially viewed new, technology-basedfirms simply as small versions of large, establishedfirms. Large, established firms most often operatein well defined markets and industries, empha-sizing replication efficiency and arms-lengthtransactions with their customers. Most frame-works of corporate strategy have been developedfor such firms. These frameworks have then beenexplicitly or implicitly adopted in studies focusingon new, technology-based firms. This process hascontributed the existing bias in the pool ofresearch on new, technology-based firms.

Table I presents a simplifying summary of theunderlying assumptions of the atomistic andsystemic approaches to research on new, tech-nology-based firms. It is the feeling of the authorthat the systemic assumptions may be more illus-trative of the majority of new, technology-basedfirms. This is not to suggest that the ‘atomistic’assumptions would be universally false. It ismerely contended that systemic assumptions maybe better suited to describe the ‘average’ new,technology-based firm.

Contention 1 holds that, contrary to manygeneral beliefs, the majority of new, technology-based firms are not aggressively growth oriented.The above discussion makes it clear why this isso. The market niches, or customer sets, targetedby most new, technology-based firms are so smallthat growth is not possible without radical alter-ation of the product and service offering of thenew, technology-based firm. In addition, managingrapid growth is difficult, and maintaining rapidgrowth requires considerable financial resources.A considerable fraction of new, technology-basedfirms are service firms, for which economies ofscale usually are not available. Even many of theproduct oriented new, technology-based firms arefirms for which the tangible product offered isactually a part of customized service. The fewexamples of miraculous growth, mostly from the

New Technology Firms 197

U.S.A., have sometimes mistakenly been consid-ered as representative of the aspirations of all new,technology-based firms.

Contention 2 holds that the traditional marketbased approach to analyzing new, technology-based firms is largely misleading. Especially formany service intensive new, technology-based

firms, there is no well defined target market. Manynew, technology-based firms become an organicpart of an innovation network, developing inten-sive links with their customers and suppliers. Suchfirms effectively modify their technology offeringto suit the needs of their customer set. The targetmarket of such firms presents itself in the form

198 Erkko Autio

TABLE ISummary of the underlying assumptions of the atomistic and systemic approaches to research on new, technology-based firms

Number Standard assumption of the atomistic approach Contention of the systemic approach to research on new, to research on new, technology-based firms technology-based firms

01 New, technology-based firms are aggressively Most new, technology-based firms are small and aim to stay growth oriented small

02 New, technology-based firms operate in a well New, technology-based firms are often better characterized in defined market and or industry environment terms of the basic technologies exploited and on the basis of

the customer set they serve, not necessarily in terms of the target market they serve

03 The relationship between new, technology-based The relationship between new, technology-based firms and firms and their environment is essentially their environment is essentially organic in nature: new, mechanistic in nature: new, technology-based technology-based firms often forge interaction intensive firms produce goods and services which are links with various users and suppliers of technology, entering sold to a more or less passive market into intense and interactive relationship with these

04 A sufficient basis to categorizing new, In addition to products and services, the transformator role technology-based firms is constituted by the that a new, technology-based firm plays in the innovation products or services they produce network can have a pervasive impact on its character

05 The barriers to growth in new, technology- The technological system in which a new, technology-based based firms, both internal and external, can be firm operates, often imposes important constraints on the removed through conscious policy measures strategic degrees of freedom available to these firms. Many

such constraints cannot be effectively removed through policy measures

06 Small technology intensive firms are small Small technology intensive firms and large established firms versions of large, established firms are fundamentally different in many respects. In the area of

innovation, the advantages of small technology intensive firms are essentially functional. The advantages of large, established firms in innovation are essentially resource based. The different advantages enjoyed by small and large firms often make them enter into co-operative relationships in which the dynamic complementarities of small and large firms are exploited

07 New, technology-based firms are similar in all The characteristics of the regional economic environment industrialized economies and of the regional research and technology base are often

reflected in the characteristics of new, technology-based firms emerging in the region

08 The main impact of new, technology-based The main impact of new, technology-based firms is delivered firms is delivered through rapid organic growth through technology interactions in innovation networks

09 New, technology-based firms are essentially New, technology-based firms are essentially concentrations concentrations of financial resources and of technological competencesentrepreneurial spirit

10 Risk taking is a characteristic feature of new, Most new, technology-based firms are risk aversetechnology-based firms

of a customer set, not in the form of a set ofexisting and potential customers with similarpreferences and buying behavior.

Contention 3 holds that the view of the tradi-tional research on new, technology-based firms hasessentially been a mechanistic one. Such a viewassumes a more or less passive market environ-ment, in which the customers are kept at arm’slength. The view held by the systemic approach toresearch on new, technology-based firms is thatthe relationship between a new, technology-basedfirm and its operating environment is essentiallyan organic one. A new, technology-based firmbecomes an organic part of its operating environ-ment, such as an innovation network, rather thanoperating in a well defined market environment.

Contention 4 holds that in addition to catego-rizing new, technology-based firms along productsand services, their transformator role played inthe innovation network should be taken intoaccount. For example, Stankiewicz distinguishesbetween three functional types of new, technology-based firms, namely, product producers, technicalconsultancies, and technological asset firms(Stankiewicz, 1994). Of these, the two first onesrepresent the traditional service and manufacturingfirms, and the third type focuses on developingnew technologies and commercializing themthrough indirect arrangements, such as licensingarrangements.

Contention 5 holds that the traditional view ofthe growth of new, technology-based firms is toosimplistic and mechanistic. The systemic view putforward in the present article is that the techno-logical system and the innovation network, inwhich a new technology-based firm operates, oftenimpose important constraints on the strategicdegrees of freedom available to new, technology-based firms. A new, technology-based firm cannoteasily be detached from its systemic environment.It is thus proposed that the traditional view that allgrowth barriers can be removed through consciousmeasures is likely to be a too optimistic one.

Contention 6 holds that in the traditionalresearch on new, technology-based firms, thedynamic complementarities of small and largefirms have not always been sufficient considera-tion. When atomistic competition between firmsis assumed, with the explicit or implicit assump-tion concerning the existence of a well defined

market, new, technology-based firms have oftenbeen treated simplistically as small versions oflarge firms. This simplistic approach completelyfails to acknowledge that small and large firms areessentially different in many respects, and thatthey seldom compete directly between each other.As, for example, Rothwell and Pavitt have sug-gested, the relationship between small and largefirms is one in which dynamic complementaritiescan often be exploited. Instead of viewing new,technology-based firms as small versions of largefirms, it is suggested that they should be mostoften viewed as complementary participants of aninnovation network.

Contention 7 holds that new, technology-basedfirms are different in different national andregional economic environments. One oftenrepeated oversimplification stemming from thetraditional atomistic treatment of new, technology-based firms is that they have been assumed to bemore or less similar in all industrialized econ-omies. A direct corollary of the systemic approachput forward in the present study is that character-istics of the operating environment of a new,technology-based firm are often reflected in it. Thecontention of the present study is that the regionaleconomic environment of a new, technology-basedfirm often shapes it as the firm itself shapes itsenvironment.

Contention 8 holds that the main impact ofnew, technology-based firms in technoeconomicsystems is not delivered through rapid organicgrowth but through other mechanisms. Empiricalstudies show that the majority of new, technology-based firms are small and stay small. This impliesthat the main economic impact of new, tech-nology-based firms may be delivered throughother mechanisms than through rapid organicgrowth. In the present study, it is suggested thatthe main impact of new, technology-based firmsmay be delivered through catalyzing technologyflows in innovation networks.

Contention 9 holds that new, technology-basedfirms should be defined primarily as concentra-tions of technological competences. The tradi-tional research on new, technology-based firmsoften transcends the impression that new, tech-nology-based firms are essentially concentrationsof entrepreneurial spirit and of more or less scarcefinancial resources. The contention held in the

New Technology Firms 199

present study is that this is only part of the truth.It can even be questioned to what degree a new,technology-based firm, which is immersed inan innovation network, actually can be labeledas entrepreneurial. Such a firm is often morereminiscent of a research and developmentarrangement than of a classical Schumpetarianentrepreneurial firm.

Contention 10 holds that the often held assump-tions concerning aggressive growth orientationand the simplistic notion of heroic Schumpetarianentrepreneur have contributed to the widely heldbelief that most new, technology-based firms arenot adverse to risk taking. The economic benefitsobtained through rapid growth and a rapid increasein the value of the firm have been seen to consti-tute the entrepreneurial reward to this risk taking.The contention held in the present study is that inmost new, technology-based firms, the risk levelis low or at most moderate, and that most new,technology-based firms actually are risk averse.For example, all that a small software firm reallyneeds is a personal computer, and even that can beleased. The risks involved in a new, technology-based firm become considerable only if it embarkson a heavy investment program, such as a longterm research and development project. In suchventures, both the market and technological riskscan of course be considerable. If the nicheoccupied by a small technology intensive firmalready provides it with a healthy cash flow, itwould, in general, be foolish for such a firm toembark on a risky long term research anddevelopment project.

3. Exploring the NTBF phenomenon

Much of the existing body of empirical researchon new, technology-based firms explores variouscharacteristics of these firms. In this ‘atomistic’research tradition, new, technology-based firmshave been analyzed more or less in isolation fromtheir environment. Environmental influences, ifany, have largely been assumed to manifestthemselves in the form of normal market andcompetitive forces. This research tradition hasproduced volumes of data on the characteristics ofindividual new, technology-based firms, and inparticular, on their growth dynamics.

A relatively small fraction of existing studies

on NTBF’s have asked the question ‘Why?’. Whyis the number of NTBF’s increasing rapidly? Whydo NTBF’s exist in the first place? What is theessence of the NTBF phenomenon? Even thoughsuch questions fall more naturally in the realm ofmacroeconomists, it is useful to discuss them alsoin the context of microeconomic and managementresearch on new, technology-based firms.

Theories and hypotheses to explain the emer-gence of new, technology-based firms have beenproposed by a number of different schools ofeconomic thought. The emergence of new, tech-nology-based firms can be interpreted as a signof changing patterns of industrial organization.Many of the potential explanations for theemergence of new, technology-based firms areindeed more or less structural in nature. Sometheories, such as the ones proposed by populationecologists, contain a strong sociological compo-nent. In here, three partially overlapping structuralexplanations for the emergence of new, tech-nology-based firms are discussed.

3.1. Schumpetarian explanations: Mark I and Mark II models

Schumpeter was one of the first economists tobring technology into the focus of economicanalysis. His early model of industrial innovation,the Mark I model, relied heavily on the entrepre-neur as the ultimate force driving the emergenceof new innovations (Freeman, 1982, pp. 211–214).In his early model of industrial innovation,Schumpeter gave a central role to the heroic‘entrepreneur’ as the agent introducing new‘combinations’ into the realm of economic life(Schumpeter, 1934). According to Schumpeter, thestrive toward replication efficiency effectivelyprevented large, established firms from exploringwith new technologies and from inventing new‘combinations’ (Schumpeter, 1939, p. 95):

We visualize new production functions as intruding intothe system through the action of new firms founded for thepurpose, while the existing or ‘old’ firms for a time workon as before, and then react – with various characteristiclags and in various characteristic ways – adaptively to thenew state of things under the pressure of competition fromdownward shifting cost curves.

Schumpeter’s Mark II model abandonded theentrepreneur as the driving force of economic

200 Erkko Autio

change (Schumpeter, 1942). According toSchumpeter, the invention of industrial R&D hadmade it impossible for small firms to undertakethe type of long term R&D projects that he hadbecome to deem necessary for the developmentof new products. Schumpeter Mark II modelcoincides with the heyday of the Fordist massproduction paradigm.

Both of the Schumpeter models are connectedto long Kondratieff cycles in economic develop-ment. At the early stage of the cycle, new tech-nological breakthroughs, or new ‘combinations’,are introduced by entrepreneurs. The early inno-vators act as pioneers which both demonstrate thefeasibility of the new technology and set anexample which encourages new players to enterthe new industry. As the cycle becomes consoli-dated, large firms may enter the arena, forexample, by swallowing up the new, technology-based firms or by simply pushing them out of themarket by using their superior investment power.The ‘Schumpetarian’ explanation to the new,technology-based firm phenomenon can be foundin this ‘swarming’ (Freeman, 1982, p. 215) of newfirms. The ‘Schumpetarian’ explanation for thenew, technology-based firm phenomenon is illus-trated in Figure 1.

Fig. 1. Schumpetarian explanation for the new, technology-based firm phenomenon.

3.2. The emergence of manufacturing networks

The Schumpetarian explanation helps explain theswarming of new, technology-based firms in theearly 20th century and the other wave of new,technology-based firms coinciding with theemergence of information intensive techno-economic paradigm during the late 1950’s andearly 1960’s. It does not explain, however, whythe number of new, technology-based firms haskept on increasing during the 1970’s, 1980’s, and

1990’s, instead of falling during the schumpetarianconsolidation phase. Clearly, complementaryexplanations are needed to explain this phenom-enon. One such explanation can be found in thedownscaling and networking trends affectingmany industries.

A simplifying definition of the manufacturingnetworking trend is that it is a process in which ahorizontal dimension is added to the traditionallinear manufacturing value chains (Porter, 1985)in industry. Marceau reflects on this process,making a distinction between chains, clusters, andcomplexes in production (Marceau, 1992;Dodgson, 1993, p. 42). One argument made byMarceau, Dodgson, and others is that the emer-gence of new flexible manufacturing technologiesis drastically increasing the strategic options whenorganizing replication intensive activities, and thatthe general downscaling trend is one consequenceof this increase.

The downscaling trend is a real and a drasticone in most manufacturing industries, but par-ticularly so in electronics. In their study, Suarez-Villa and Han report that the average plant sizein electronics has fallen from 300 employees in1960 to under 100 employees in 1990 in theUnited Kingdom (Suarez-Villa and Hahn, 1990;Suarez-Villa, 1994). In the U.S.A., the corre-sponding figures are 200 employees in 1960 andapproximately 100 employees in 1990. In Japan,the home of many of the new manufacturingphilosophies, such as just-in-time production andlean production, the downsizing trend is alsovisible. The corresponding figures for Japan areapproximately 100 employees in 1960 andapproximately 50 employees in 1990. This down-sizing trend has been so strong that it has leadsome organization theorists to advocate theemergence of a new networking form of industrialorganization (Miles and Snow, 1986; Saxenian,1991; Langlois and Robertson, 1992), sometimeslabeled as ‘virtual corporation’ (Davidow andMalone, 1992) or ‘value constellation’ (Normannand Ramirez, 1993).

The emergence of manufacturing networkscreates opportunities for new, technology-basedfirms especially in such industrial sectors wherethe basic technology presents itself in the form ofa platform upon which different configurations ofsystems can be built. In such sectors, oppor-

New Technology Firms 201

tunities are often created for specialized compo-nent suppliers (Pavitt, 1984). Examples of suchsectors are, for example, car manufacturing indus-try and numerous electronics related industries,such as laptop computers and many instrumenta-tion sectors.

From the point of view of the present discus-sion, essential in the manufacturing networkingtrend is that limits to growth are largely dictatedat the network level. Storper and Harrison pointout that manufacturing networks, or productionsystems, often have an input-output structure,which is representative of the production system,and complements the input-output structures ofindividual firms (Storper and Harrison, 1991).This kind of systems level integration oftenimposes constraints on the growth of individualactors belonging to such a system. On the otherhand, it can be expected that the chances ofsurvival within such a system are greater thanoutside it. Both of these factors offer feasibleexplanations to the phenomenon of rapid increasein the number of relatively small new, technology-based firms during the 1970’s, 1980’s, and 1990’s.

3.3. The emergence of innovation networks

The emergence of innovation networks (Crevoisierand Maillat, 1991) is a partially overlappingphenomenon with the emergence of manufacturingnetworks. Particularly in high technology sectors,the borderline between replication intensivefunctions and development intensive functions hasa tendency to become blurred. There are, however,many respects in terms of which the networkingtrends affecting replication intensive and devel-opment intensive activities differ from each other.Therefore these are discussed separately.

There is a general consensus that the rate oftoday’s technological change is high. Manyauthors argue that not only the speed of innova-tion is increasing, but also dynamics of theinnovation process itself is changing (Rothwell,1994a; Rothwell, 1994b; von Hippel, 1988;Daghfous and White, 1994). A number of con-ceptual models have been proposed to depict thechanging dynamics of innovation processes(Rothwell, 1992; Kline and Rosenberg, 1986;Forrest, 1991; Lundvall, 1992). Common to all ofthese models is increased reliance on external

knowledge and technology sources in innovation.Based on findings of a number of empirical studiesRothwell develops a model of “the fifth genera-tion innovation process” or the “systems integra-tion and networking model”. Essential to thismodel is that the various subprocesses of a macro-level innovation processes are distributed over arange of independent but interconnected actorsbelonging to the same innovation network. Thiskind of network structure, according to Rothwell,offer superior opportunities for technology fusion,increased flexibility, and speed of project execu-tion. Such innovation networks, according toRothwell, depict strong interactive links bothdownstream to user level and upstream to supplierlevel. Information is also shared horizontallythrough various kinds of collaborative arrange-ments, such as R&D consortia and strategicalliances.

Stankiewicz proposes that the main factorunderlying the shift in the locus of innovation isthe general ‘scientification’ of technologies(Stankiewicz, 1990). According to Stankiewicz,the relative importance of generic, articulatedknowledge is increasing, due to the increasingcomplexity and scientification of technology. Thisis particularly relevant in science-based basictechnologies, such as electronics, materials tech-nologies, and biotechnology. The implications ofthese trends from the point of view of technolog-ical innovation include, according to Stankiewicz(Stankiewicz, 1990; Carlsson and Stankiewicz,1991), increased pace of technological innovation,increased generity of technologies, increased levelof articulation and transferability of technologies,and increased fusibility of technologies.

The above listed trends can be expected to opennew possibilities for specialized new, technology-based companies to find niches in innovationnetworks. Innovation networks can be expected tochange the balance between economies of scaleand economies of scope in such a way that thelatter become increasingly important. If the abovediscussed trends hold, an increasing number ofnew, technology-based firms can be expected tosurvive by providing specialized inputs intocomplex innovation networks (Rothwell, 1991,p. 95).

In the area of innovation, small new, tech-nology-based firms enjoy many functional advan-

202 Erkko Autio

tages over large, established firms (Rothwell,1991; Rothwell, 1983). Such functional advan-tages include low degree of organizational rigidity,speed, flexibility, efficient internal communica-tion, well working interfaces between researchand development and other functions of thefirm, and efficiency in research and development.Large firms, for their part, often possess superiorresource-based advantages over small firms, suchas professional management, ability to buildand operate efficient external communicationnetworks, access to distribution channels, finan-cial resources, and ability to carry out long termresearch and development projects. The differentcharacter of such advantages creates potentialdynamic complementarities between small andlarge firms in innovation. The existence of suchdynamic complementarities offers one feasibleexplanation for the emergence of innovationnetworks.

4. The systemic environment of a new, technology-based firm

The partially overlapping potential explanationsconcerning the phenomenon of rapid increase inthe number of slow growth new, technology-basedfirms all emphasize the importance of systemicfactors. In the Schumpetarian explanations, thesystemic factor is given the form of a scientificresearch system, which makes new scientificbreakthroughs available to innovative entrepre-neurs. In the manufacturing network explanation,the systemic factor is given the form of newmanufacturing technologies and the form of themanufacturing network, of which a new, tech-nology-based firm becomes an organic part. In theinnovation network explanation, the systemicfactor is given the form of basic technologies andthe innovation network, of which a new, tech-nology-based firm becomes an organic part.

The systemic environment, in which a new,technology-based firm operates, can be givenmany forms. Even Porter discusses strategicgroups (Porter, 1980). A strategic group, accordingto Porter, consists of firms whose competitivestrategies complement each other. The firms may,for example, target different market segments.This approach, however, may not be an optimalone for the study of new, technology-based firms.

To understand why, it is necessary to take a brieflook at the various views of the firm.

The traditional neoclassical approach todefining a firm has been to define it as a unit ofproduction. This production unit was viewed asbeing exposed to various competitive and marketforces, with little or no power to influence its envi-ronment. This view has long been recognized astoo simplistic (Kay, 1984). The black box ofproduction was opened up by transaction costeconomists, who viewed the firm as a set of inter-nalized transactions (Coase, 1937; Williamson,1975), or as a nexus of contracts (Fransman,1993). This approach proved useful for manysituations. It is not very well suited, however, toopening up the black box of research and devel-opment. This is the main activity of most new,technology-based firms. To deal with research anddevelopment, a firm has to be viewed essentiallyas a resource based information processing unit(Penrose, 1959), or as a reservoir of knowledgeand organizational competencies (Nelson andWinter, 1982).

Recently, the resource and competence view ofindustrial firms has gained widespread acceptance(Teece et al., 1990; Prahalad and Hamel, 1990;Dosi and Teece, 1993; Pavitt, 1992). To a greaterextent than many other types of firms, new, tech-nology-based firms can be viewed as concentra-tions of technological competencies. For new,technology-based firms, these competencies areessentially technological in nature. It can thus beexpected that characteristics of the technologyenvironment in which a new, technology-basedfirm operates exercise important influence on it.

Instead of target market or industry, we argue,a more useful systemic framework against whichto analyze new, technology-based firms is thetechnological system (Carlsson and Stankiewicz,1991) in which a new, technology-based firmoperates. Carlsson and Stankiewicz define tech-nological systems as: “. . . a network of agentsinteracting in a specific economic/industrial areaunder a particular institutional infrastructure or setof infrastructures and involved in the generation,diffusion, and utilization of technology”. Otherdefinitions add the total pool of the basic tech-nology itself to the above definition (Autio andHameri, 1994). Essential to such a systemic frame-work is that it is not driven solely by market

New Technology Firms 203

forces. An essential part of the dynamics of sucha system is constituted by technology flows andby the processes by which technology is devel-oped and disseminated. A technological systemdoes not have to be confined within the bound-aries of any particular industry. Truly paradigmatictechnological systems can pervade whole sets ofindustries and even economies.

A new, technology-based firm is connected toa technological system through various kinds oftechnology transfer mechanisms. From the pointof view of a new, technology-based firm, the mostimportant elements of a technological system arenormally constituted by various sources and usersof technology. One classification of such sourcesand users is presented in Figure 2 (Bachmann,1993, pp. 84–87; Autio, 1993).

Fig. 2. Classification of technology sources available for thenew, technology-based firm.

A new, technology-based firm can connect toboth domestic and foreign, and to both public andprivate sources and users of technology. Thepatterns by which such connections are made canbe expected to vary from one technological systemto another. Also the transformator role played bya new, technology-based firm within a technolog-ical system can be expected to affect thesepatterns. Autio and Geust have identified two suchtransformator roles, the essential role of whichdepends on the degree of paradigmatic behaviorof the system (Autio and Geust, 1994, p. 18).These are shown in Figure 3.

The transformator roles of new, technology-based firms, as depicted in Figure 3, require someclarification. According to the schematic presen-tation in Figure 3, at least two transformator rolescan be found for new, technology-based firms in

technological systems, based on their functionalrelationship with the articulation process of basictechnologies, as defined bs Clark and Juma (Clarkand Juma, 1987, p. 108). Science based NTBF’sare relatively more active in the transformation ofscientific knowledge into basic technologies.Engineering based NTBF’s are relatively moreactive in broadening the scope of applications ofbasic technologies (Autio, 1994b). The nature ofoutputs of these transformation processes can vary,depending on the paradigmatic nature of therespective basic technologies, as illustrated inFigure 3.

The nature of basic technologies largely deter-mines the nature of technological systems. InFigure 3, a distinction is made between two basictypes of basic technologies. These are labeledparadigmatic basic technologies and industry-specific basic technologies. These two types ofbasic technologies differ from each other mainlyin terms of the scope of their potential applica-tions. For paradigmatic basic technologies, asdefined in Figure 3, the scope of applications isbroad, extending over several traditional sectorsof industry. Paradigmatic basic technologies arehighly fusible and can thus be integrated with abroad range of other basic technologies. The scopeof industry-specific basic technologies does notextend beyond the specific industrial or tech-nology area for which they have been developed.

Also Balconi puts forward the contention that

204 Erkko Autio

Fig. 3. Functional roles of science based and engineeringbased NTBF’s in industry specific and in paradigmatic tech-nological systems.

the characteristics of ‘industry knowledge base’(Balconi, 1993, p. 483) largely determine thestructuring of the industrial apparatus exploitingit. Balconi specifically emphasizes the importanceof ‘depth’ and ‘codifiability’ of technology in thisrespect.

To illustrate the nature of possible systemicinfluences on new, technology-based firms, weconstruct a tentative classification of them. Thetentative taxonomy reflects the interrelationshipsbetween the transformator role of a new, tech-nology-based firm, as illustrated in Figure 3, andthe characteristics of their respective basic tech-nologies, likely innovator roles (Autio, 1994a),sources of differentiation, and the location ofmarkets and sources of technology. The tentativeclassification is shown in Table II.

In Table II, the innovator roles are definedaccording to the novelty of basic technologiesemployed by the firm and according to the noveltyof the market environment targeted by the firm.Application innovators employ existing basictechnologies in an existing market environment.Technology innovators introduce new basictechnologies in an existing market environment.Market innovators employ existing basic tech-nologies in a new market environment. Paradigminnovators develop new basic technologies fornew market environments. The knowledge basesof the four transformator types are expected todiffer from each other in terms of codifiability,systemic character, and the source of specificity.A systemic knowledge base offers a platform uponwhich various kinds of configurations of systemicproducts can be built. The innovator role and the

characteristics of the knowledge base can beexpected to influence the nature of likely sourcesof differentiation, and the likely location oftechnology sources.

5. Conclusion

The most important distorting effects of theexisting growth myopia in the research on new,technology-based firms are probably found in thelevel of industrial policy. Recently, for example,many countries have started to experiment withpublic venture capital, in the explicit hope ofalleviating the effects of unemployment. It hasbeen simplistically argued that the lack of patientequity capital is the most important barrierhindering the growth of new, technology-basedfirms, and that economic growth could be inducedby simply pumping more public funds into theventure capital sector. Much of such argumenta-tion completely neglects the growth constraintsimposed by systemic factors.

The above said does not mean that venturecapital would not be a feasible tool of industrialand technology policy. Venture capital is arguablythe one single most efficient tool with which toinduce growth in new, technology-based firms.This is because venture capitalists can be expectedto be competent and, through hands-on participa-tion, to actively drive the innovative new firmtowards growth. The argument of the presentpaper is that the traditional policy tools, such asventure capital, can normally be applied only ona small fraction of new, technology-based firms.The greater the systemic constraints imposed on

New Technology Firms 205

TABLE IITentative classification of interrelationships between transformator roles, innovator roles, and systemic influences

Characteristic Engineering based Science based Engineering based Science based industry specific industry specific paradigmatic paradigmatic

Likely innovator role Application innovator Technology innovator Market innovator Paradigm innovator

Characteristic of • tacit, complex • codified, complex • mixed, complex • codified, complexknowledge base • non-systemic • non-systemic • systemic • systemic

• application specific • industry specific • concept specific • function specific

Source of Customer Industry Product or service Scientific disciplinedifferentiation concept

Location of Industry Academic research Industry, RDO’s Academic researchtechnology source

a new, technology-based firm, the less efficientsuch policy tools are likely to be. In addition, itis likely that there are natural limits constrainingthe emergence of ‘true’ research spin-offs with alarge growth potential. These limits are likely tobe connected with the breadth of the nationalresearch base. It is likely that such limits cannotbe overcome by simply increasing the amount offunding allocated on, for example, venture capital.

One obvious implication of the above argu-mentation is that policy measures should becorrectly targeted. A second, perhaps less obvious,implication is that policy measures should beredesigned to take into account the effect ofsystemic constraints. This means that if innova-tion networks are increasing in importance, withan identifiable input-output structure at thenetwork level, this development calls for meso-level policy measures. Instead of single firms,policy measures should be reoriented to targetnetworks.

Many such policy measures are, of course,already being employed. In Finland, for example,national technology programs have been carriedout since mid-1980’s. The aim of these programsis to diffuse best practice and to catalyze thetechnology development and diffusion processesin selected industry and technology sectors. It isthe belief of the author of the present paper thatmore such policy measures could be developed.Another question, that is not addressed in here, iswhether there is a real need for such policymeasures or not. It suffices to note that manygovernment-funded studies that focus on new,technology-based firms do not even ask thisquestion. They only start from such an axiom andfocus on studying what kind of policy measuresare needed the most.

The systemic approach put forward in thepresent study could also shed more light on the‘true’ role of science parks as tools of industrialand technology policy. Many researchers andpolicymakers have expressed their disappointmenton the fact that the European science parks havenot become the hotbeds for economic growth thatthey were expected to become (Monck et al.,1988). The classical justification of science parkshas been that they enhance inter-firm communi-cation and the exploitation of inter-firm synergieswithin science parks, thus providing a favorable

environment for growth. This goal has not beenachieved in many science parks. If the systemiccontentions put forward on the present paper hold,this should not even be expected.

If most new, technology-based firms are morereminiscent of R&D networking arrangements,rather than atomistic firms operating in a passivemarket, the ‘true’ role of science parks could besimply to accommodate modern network arrange-ments. According to the systemic view, the ‘true’role of science parks, one in which scienceparks obviously have been highly successful, isto provide shelter and inspiring environment fornetwork firms. Such a role is supported by thefinding of Olofsson and Wahlbin, according towhich university spin-off firms provide approxi-mately 40% of all research and developmentsubcontracting that Swedish established firmsacquire from Swedish industries and branch orga-nizations (Olofsson and Wahlbin, 1993; Olofssonand Wahlbin, 1994). This is an important signalduring an era when established industrial firmsincreasingly move toward lean organizations, withcorporate headquarters either completely elimi-nated or at least drastically reduced. According tothe systemic view, science parks could be viewedas the playing the important role of housing the‘headquarters’ of modern innovation networks.Naturally, in such environments, high growthfirms may emerge, and they are highly welcome.One merely should not attach unrealistic expecta-tions to science parks in this regard.

The present discussion does not aim to suggestthat new, technology-based firms would not be animportant phenomenon. They are. The argumen-tation of the present paper has merely contendedthat the true role of new, technology-based firmsshould be recognized. Only this way, realistic andbalanced industrial and technology policymeasures can be designed. It should also be keptin mind that excessive extrapolations on the basisof the networking trend should not be made, either.For example, Hobday and Senker remind us thatthere are real counterweights to the networkingtrend (Senker, 1994; Hobday, 1994). The keywordin here is balance. The balance of the dynamiccomplementarities between small and large firmsin innovation is likely be different in differenttechnological environments. The key question ofpolicy formulation is to recognize the optimal

206 Erkko Autio

balance and to design the policy measures, if theyare needed, accordingly.

References

Anon, 1969, ‘La Route 128’, Le Progrès Scientifique(October-November).

Autio, E., 1993, Technology Transfer Effects of New,Technology-Based Companies, Espoo: Helsinki Universityof Technology, Institute of Industrial Management, 1993:1.

Autio, E., 1994a, ‘Four Types of Innovators: A Conceptualand Empirical Study of New, Technology-Based Firms asInnovators’, Halmstad, Sweden: 8th Nordic Conference onSmall Business Research, Halmstad Business School.

Autio, E., 1994b, ‘Interrelationships Between SystemicDeterminants and the Technology Behavior of New,Technology-Based Firms’, Jönköping, Sweden: Inter-national Workshop on Entrepreneurship and Innovation inSME’s, Jönköping Business School.

Autio, E. and N. Geust, 1994, ‘External Technology Linkagesof New, Technology-Based Firms in Engineering Basedand in Science Based Industries: Implications forInnovation Management’, Manchester, UK: InternationalConference on High Technology Small Firms, ManchesterBusiness School.

Autio, E. and A-P. Hameri, 1994, Technological Systems:Structures, Dynamics, and Sources of Change, Espoo:Helsinki University of Technology, Institute of IndustrialManagement, Working papers 1994: 1.

Autio, E., N. Kaila, R. Kanerva and I. Kauranen, 1989, UudetTeknologiayritykset (New, Technology-Based Firms),Helsinki: Finnish National Fund for Research andDevelopment SITRA, B 101.

Bachmann, R., 1993, Technology Transfer with Spin-OffCompanies: An Empirical Study Based on Companies SpunOff from Cambridge University and the TechnicalResearch Center of Finland, VTT, Espoo: HelsinkiUniversity of Technology, Institute of IndustrialManagement.

Balconi, M., 1993, ‘The Notion of Industry and KnowledgeBases: The Evidence of Steel and Mini-Mills’, Industrialand Corporate Change 2(3), 471–507.

Barber, J., J. S. Metcalfe and M. Porteous, 1990, Barriers toGrowth in Small Firms, London: Routledge.

Boyer, K. D., 1984, ‘Is there a Principle for DefiningIndustries?’, Southern Economic Journal 50.

Carlsson, B. and R. Stankiewicz, 1991, ‘On the Nature,Function, and Composition of Technological Systems’,Journal of Evolutionary Economics 1, 93–118.

Clark, N. and C. Juma, 1987, Long-Run Economics: AnEvolutionary Approach to Economic Growth, London:Pinter Publishers.

Coase, R. H., 1937, ‘The Nature of the Firm’, Economica 4,386–405.

Cooper, A. C., 1970, ‘The Palo Alto Experience’, IndustrialResearch (May).

Cooper, A. C., 1971, The Founding of Technologically-BasedFirms, Milwaukee: The Center for Venture Management.

Cooper, A. C., 1972, ‘Spin-off Companies and TechnicalEntrepreneurship’, IEEE Transactions on EngineeringManagement 1 (February).

Cooper, A. C., 1973, ‘Technical Entrepreneurship: What doWe Know?’, R&D Management 3(2), 59–65.

Courtney, N. and A. Leeming, 1994, Meeting the Needs ofSmall IT Firms, Manchester, UK: International Conferenceon High Technology Small Firms, Manchester BusinessSchool.

Crevoisier, O. and D. Maillat, 1991, ‘Milieu, IndustrialOrganization, and Territorial Production System: Towardsa New Theory of Spatial Development’, in R. Camagni(ed.), Innovation Networks: Spatial Perspectives, London:Belhaven Press.

Daghfous, A. and G. R. White, 1994, ‘Information andInnovation: A Comprehensive Representation’, ResearchPolicy 23(3), 267–280.

Davidow, W. H. and M. S. Malone, 1992, The VirtualCorporation: Structuring and Revitalizing the Corporationfor the 21st century, New York: Harper & Collins.

Dickenson, P. J. and D. S. Watkins, 1971, Initial Report onSome Financing Characteristics of Small, Technologically-Based Firms and their Relation to Location, Manchester:Manchester Business School.

Dodgson, M., 1993, Technological Collaboration in Industry:Strategy, Policy, and Internationalization in Innovation,London: Routledge.

Dosi, G. and D. J. Teece, 1993, Organizational Competencesand the Boundaries of the Firm, CCC Working Paper No93-11, Berkeley: University of Berkeley.

Dougier, H., 1971, ‘Risk, Money, Motivation: The Venturesof Venture Capital in Europe’, European Business 28.

Doutriaux J. and B. Peterman, 1982, Technology Transfer andAcademic Entrepreneurship at Canadian Universities,Ottawa: Technological Innovations Studies Program.

Doutriaux, J., 1987, ‘Growth Patterns of AcademicEntrepreneurial Firms’, Journal of Business Venturing 2,285–297.

Flamholtz, E. G., 1990, Growing Pains: How to Manage theTransition from an Entrepreneurship to a ProfessionallyManaged Firm, Oxford: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Forrest, J. E., 1991, ‘Models of the Process of TechnologicalInnovation’, Technology Analysis & Strategic Management3(4), 439–453.

Forseth, D. A., 1965, The Role of Government-SponsoredResearch Laboratories in the Generation of NewEnterprises – A Comparative Analysis, S M Thesis,Cambridge, Massachusetts: Massachusetts Institute ofTechnology, Sloan School of Management.

Fransman, M., 1993, Information, Knowledge, and Theoriesof the Firm, Edinburgh: Institute of Japanese-Europeantechnology studies.

Freeman, C., 1971, The role of Small Firms in Innovation inthe United Kingdom Since 1945, Report 6, London:Committee of Inquiry on Small Firms.

Freeman, C., 1982, Economics of Industrial Innovation,London: Pinter Publishers, London.

Gibbons, M. and D. S. Watkins, 1970, ‘Innovation and theSmall Firm’, R&D Management 1(1).

Gould, A. and D. Keeble, 1984, ‘New Firms and Rural

New Technology Firms 207

Industrialization in East Anglia’, Regional Studies 18,189–201.

Hobday, M., 1994, ‘The Limits of Silicon Valley: A Critiqueof Network Theory’, Technology Analysis & StrategicManagement 6(2), 231–244.

Hull, C. and B. Hjern, B., 1989, Helping Small Firms Grow:An Implementation Approach, London: Routledge.

Kauranen, I., M. Takala, E. Autio and M. Kaila, 1990, ThreeFirst Years: A Study on the First Phases of a New SciencePark and of its Tenants (with a summary in English),Espoo: Otaniemi Science Park, 2: 1990.

Kay, N., 1984, The Emergent Firm, London: Macmillan.Keeble, D. and T. Kelly, 1986, ‘New Firms and High-

Technology Industry in the United Kingdom: The Case ofComputer Electronics’, in D. Keeble and E. Wever (eds.),New Firms and Regional Development in Europe, London:Croom Helm.Kellock, M., 1992, On Barriers to Growth,Cranfield, United Kingdom: Cranfield School ofManagement.

Kline, S. J. and N. Rosenberg, 1986, ‘An Overview onInnovation’, in The Positive Sum Strategy: HarnessingTechnology for Economic Growth, Washington: NationalAcademy Press.

Langlois, R. N. and P. L. Robertson, 1992, ‘Networks andInnovation in a Modular System: Lessons from theMicrocomputer and Stereo Component Industries’,Research Policy 21, 297–313.

Little, Arthur D., 1977, New Technology-Based Firms in theUnited Kingdom and in the Federal Republic of Germany,London: Wilton House Publications.

Lumme, A., 1994, Potential for Growth: SocietalContributions of the Most Promising Technology-BasedEntrepreneurial Companies in Finland – EmpiricalEvidence, Manchester, U.K.: International Conference onHigh Technology Small Firms, Manchester BusinessSchool.

Lundvall, B-Å (ed.), 1992, National Systems of Innovation:Towards a Theory of Innovation and Interactive Learning,London: Pinter Publishers.

Marceau, J., 1992, Reworking the World: Organizations,Technologies, and Cultures in Comparative Perspective,Berlin: De Gruyter.

Miles, R. E. and C. Snow, 1986, ‘Organizations: NewConcepts and New Forms’, California ManagementReview 28(3), 62–73.

Monck, C. S. P., R. P. Porter, P. Quintas, D. J. Storey and P.Wynarczyk, 1988, Science Parks and the Growth of HighTechnology Firms, London: Croom Helm.

Nelson, R. and S. G. Winter, 1982, An Evolutionary Theoryof Economic Change, Cambridge, Massachusetts: TheBelknap Press.

Normann, R. and R. Ramirez, 1993, ‘From Value Chain toValue Constellation: Designing Interactive Strategy’,Harvard Business Review (July-August), 65–77.

Oakey, R., 1984, High Technology Small Firms, London:Pinter Publishers.

Oakey, R., 1993, ‘High Technology Small Firms: A MoreRealistic Evaluation of their Growth Potential’, in B.Johannisson, C. Karlsson, D. Storey (eds.), Small Business

Dynamics: International, National, and RegionalPerspectives, London: Routledge.

Oakey, R., R. Rothwell and S. Y. Cooper, 1988, TheManagement of Innovation in High Technology SmallFirms, London: Pinter Publishers.

Olofsson C. and C. Wahlbin, 1984, ‘Technology-Based NewVentures from Technical Universities: A Swedish Case’,in Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, Massachusetts:Babson College.

Olofsson, C. and C. Wahlbin, 1987, ‘Firms Started byUniversity Researchers in Sweden – Roots, Roles,Relations, and Growth Patterns’, in Frontiers of Entre-preneurship Research, Massachusetts: Babson College.

Olofsson, C. and C. Wahlbin, 1986, ‘Technology-Based NewVentures from Swedish Universities: A survey’, inHornaday et al., Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research,Massachusetts: Babson College.

Olofsson, C. and C. Wahlbin, 1993, Teknibaserade FöretagFrån Högskolan, Linköping, Sweden: Institute forManagement of Innovation and Technology.

Pavitt, K., 1984, ‘Sectoral Patterns of Technical Change: ATaxonomy and a Theory’, Research Policy 13, 343–373.

Pavitt, K., 1992, ‘Some Foundations for a Theory of the LargeInnovating Firm’, in G. Dosi, R. Giannetti, and P. A.Toninelli (eds.), Technology and Enterprise in a HistoricalPerspective, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Penrose, E. T., 1959, The Theory of the Growth of the Firm,Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Porter, M. E., 1980, Competitive Strategy, New York: TheFree Press.

Porter, M. E., 1985, Competitive Advantage, New York: TheFree Press.

Poza, E. J., 1989, Smart Growth: Critical Choices for BusinessContinuity and Prosperity, London: Jossey-Bass.

Prahalad, C. K. and G. Hamel, 1990, ‘The Core Competenceof the Corporation’, Harvard Business Review (May-June),79–91.

Riggs, H. E., 1983, Managing High-Technology Companies,New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company.

Roberts, E. B., 1968, ‘Entrepreneurship and Technology: ABasic Study of Innovators’, Research Management 11(4),249–266.

Roberts, E. B., 1990, Strategic Transformation and theSuccess of High Technology Companies, Working papersWP #2-90, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MassachusettsInstitute of Technology, Sloan School of Management.

Roberts, E. B., 1991, Entrepreneurs in High Technology:Lessons from MIT and Beyond, Oxford: Oxford UniversityPress.

Roberts, E. B. and H. Wainer, 1966, Some Characteristics ofTechnical Entrepreneur, Working Paper 195-66,Cambridge, U.S.A.: Sloan School of Management,Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Roberts, E. B. and H. Wainer, 1968, ‘New Enterprises onRoute 128’, Science Journal (December).

Rodenberger C., McCray J., 1981, ‘Start Ups from a LargeUniversity in a Small Town’, in Frontiers ofEntrepreneurship Research, Massachusetts: BabsonCollege.

208 Erkko Autio

Rogers, C. E, 1966, The Availability of Venture Capital forNew, Technically-Based Enterprises, S M Thesis,Cambridge, Massachusetts: Massachusetts Institute ofTechnology, Sloan School of Management.

Rogers, E. M., 1983, Diffusion of Innovations, third edition,New York: The Free Press.

Rothwell, R., 1983, ‘Innovation and Firm Size: The Case ofDynamic Complementarity’, Journal of GeneralManagement 8(6), 5–25.

Rothwell, R., 1991, ‘External Networking and Innovation inSmall and Medium-Sized Manufacturing Firms in Europe’,Technovation 11(2), 93–112.

Rothwell, R., 1992, ‘Successful Industrial Innovation: CriticalFactors for the 1990s’, R&D Management 22(3), 221–239.

Rothwell, R., 1994, ‘Issues in User-Producer Relations in theInnovation Process: The Role of Government’,International Journal of Technology Management 9(5,6,7),629–649.

Rothwell, R., 1994, ‘Towards the Fifth-Generation InnovationProcess’, International Marketing Review 11(1), 7–31.

Saxenian, A., 1991, ‘The Origins and Dynamics of ProductionNetworks in Silicon Valley’, Research Policy 20, 423–437.

Schumpeter J. A., 1934, The Theory of EconomicDevelopment, Cambridge, Massachusetts: HarvardEconomic Studies Series, vol XLVI.

Schumpeter, J. A., 1939, Business Cycles: A Theoretical,Historical, and Statistical Analysis of the CapitalistProcess, Philadelphia: Porcupine Press, 1982.

Schumpeter, J. A., 1942, Capitalism, Socialism, andDemocracy, New York: Harper & Row.

Segal, Quince, Wicksteed and ISI, 1986, New Technology-Based Firms, Cambridge: Segal, Quince, and Wicksteed.

Senker, J., 1994, ‘Tacit Knowledge and Models ofInnovation’, Brighton: University of Sussex, SPRU.

Slater, R., 1987, Portraits in Silicon, London: The MIT Press.Slatter, S., 1992, Gambling on Growth: How to Manage the

Small High-Tech Firm, Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.Stankiewicz, R., 1990, ‘Basic Technologies and the Innovation

Process’, in J. Sigurdsson (ed.), Measuring the Dynamicsof Technological Change, London: Pinter Publishers.

Stankiewicz, R., 1994, ‘Spin-Off Companies from Univer-sities’, Science and Public Policy 21(2), 99–107.

Storey, D., K. Keasey, R. Watson and P. Wynarczyk, 1987,The Performance of Small Firms, London: Routledge.

Storper, M. and B. Harrison, 1991, ‘Flexibility, Hierarchy, andRegional Development: The Changing Structure ofIndustrial Production Systems and their Forms ofGovernance in the 1990s’, Research Policy 20, 407–422.

Suarez-Villa, L., 1994, Outsourcing and Regional StrategicAlliances in Small, Technologically Advanced Firms,Jönköping, Sweden: Workshop on Innovation andEntrepreneurship in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises,Jönköping Business School.

Suarez-Villa, L. and P-H. Hahn, 1990, ‘International Trendsin Electronics Manufacturing and the Strategy ofIndustrialization’, Rivista Internazionale di ScienceEconomiche e Commerciali 37, 381–407.

Teece, D., G. Pisano and A. Schuen, 1990, Firm Capabilities,Resources, and the Concept of Strategy, CCC WorkingPaper No. 90-8, Berkeley: University of Berkeley.

Teplitz, P. V., 1965, Spin-Off Enterprises from a LargeGovernment Sponsored Laboratory, S M Thesis,Cambridge, Massachusetts: Massachusetts Institute ofTechnology, Sloan School of Management.

Thurston, P., 1965, The Founding and Growth Process of NewTechnical Enterprises, S M Thesis, Cambridge,Massachusetts: Massachusetts Institute of Technology,Sloan School of Management.

Tyebjee T. and Bruno A. V., 1982, ‘A Comparative Analysisof California Start-Ups from 1977 to 1980’, in Frontiersof Entrepreneurship Research, Massachusetts: BabsonCollege.

von Hippel, E., 1988, The Sources of Innovation, New York:Oxford University Press.

Watkins, D. S., 1973, Technical Entrepreneurship: A Cis-Atlantic View, R&D Management 3(2), 65–70.

Westhead, P., 1994, Survival and Employment GrowthContrasts Between ‘Types’ of Owner-Managed High-Technology Firms, Jönköping, Sweden: InternationalWorkshop on Innovation and Entrepreneurship in SME’s,Jönköping Business School.

Williamson, O. E., 1975, Markets and Hierarchies: Analysisand Antitrust Implications, New York: The Free Press.

New Technology Firms 209