assan ln ht aren ln Dallas Theater Center the StudyGuide FY16 Mountaintop... · 2020-02-05 ·...

Transcript of assan ln ht aren ln Dallas Theater Center the StudyGuide FY16 Mountaintop... · 2020-02-05 ·...

Dallas Theater Center

This riveting play by American playwright Katori Hall takes place on April 3, 1968–the eve of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s death at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. The play itself is a fictional set of events between King and a mysterious hotel maid named Camae after the delivery of his memorable speech “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” during the sanitation worker’s strike. Throughout the play King is forced to reconcile with his own fears, temptations and conviction, and the impact of these on the future of his people.

the StudyGuide 20152016Season

Well, I don’t know what will happen now. We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it doesn’t

matter with me now. Because I’ve been to the mountaintop. And I don’t mind. Like any man, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its

place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go

up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the promised land. I may not get there with

you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people will get to the promised land.”

“I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” April 3, 1968

Memphis, Tennessee

by KATORI HALL • directed by AKIN BABATUNDEOnstage thru November 11 Wyly Theatre / Studio TheatreAT&T Performing Arts Center

“Our aim must never be to defeat or humiliate the white man, but to win his friendship and understanding. We must come to see that the end we seek is a society at peace with itself, a society that can live with its conscience. And that will be a day not of the white man, not of the black man. That will be the day of man as man.”

“Our God Is Marching On”March 25, 1965Selma, Alabama

From I am a Man! to Black Lives Matter Personhood as Resistance

(continued)

horrible things that were being done to them. To treat a human that way would

be unforgivable. But if someone was not human, or was subhuman, it wouldn’t

matter as much, right?

Slaves in America were taken from their homes, were separated from their

families, were sold to owners and were treated as their property. They were

denied so many things that we associate with being human – homes, families,

often even names – that many slaves began to believe and accept that there was

no way out. However, many refused to accept this attempt at dehumanization.

Oral histories and storytelling became vital in enslaved communities as a

reminder of their humanity – their past and hopeful future. Spirituals calling

upon God and acknowledging the existence of their souls were sung out in

the fields to help people persevere through hard labor. Any small word or

action that reinforced their humanity became an act of resistance. For another

example of the preservation of humanity as resistance, we could also look at

the prisoners living in concentration camps during the Holocaust. They were

stripped of their names and given numbers, they were stripped of their clothes

and given uniforms – all of their identifying features were taken away from

them. But, as Holocaust survivor and author Primo Levi recalls, even in such a

dire situation, prisoners found small ways to reclaim their humanity. He writes:

“We are slaves, deprived of every right, exposed to every insult, condemned

to certain death, but we still possess one power, and we must defend it with

all our strength for it is the last - the power to refuse our consent. So we must

certainly wash our faces without soap in dirty water and dry ourselves on our

jackets. We must polish our shoes, not because the regulation states it, but for

dignity and propriety. We must walk erect, without dragging our feet, not in

homage to Prussian discipline but to remain alive, not to begin to die.”

Asserting your own humanity, your own personhood, has therefore always

been an act of resistance against an oppressive system. To claim your own

individuality is to refuse to consent to the deprivation of your rights. Even

today, we hear echoes of “I am a man!” in a newly popular slogan, “Black lives

matter!” The wording is different, and the means of spreading the message –

from engraved coins in the 1700s to hashtags in the 2000s – have certainly

evolved, but across centuries, continents, and causes, the message is universal:

I am a person. I have dignity. I have a life that is equal to yours, and it matters.

is an African American playwright, journalist,

and actress from Memphis, Tennessee. Her play

Mountaintop was first produced in London in June

of 2009 and won the Olivier Award for Best New

Play in 2010. Her other plays include Hurt Village,

Hoodoo Love, Remembrance, Saturday night/Sunday

Morning, and the Hope Well. Hall has won numerous awards including the

2005 Lorraine Hansberry Playwriting Award, 2006 New York Foundation of the

Arts Fellowship in Playwriting and Screenwriting and the 2007 Fellowship of

Southern Writers Bryan Family Award in Drama.

“Are my words enough for the revolution?”

I didn’t know what revolution I wanted

to be part of, but I asked myself

this nonetheless. I’m not very

religious but I think of the

theatre as a church: it’s my

salvation in the way that I can

move people to tears

or to laughter.

That’s the first

step towards

social change:

when we see

one another in

our darkness and

our light.”

Katori Hall

-Katori Hall, 2011 katorihall.com

PIER 1 ImPORTs NEImAN mARcUs Ernst & Young LLP ExxonMobil National Corporate Theatre Fund t. howard + associates Theodore & Beulah Beasley Foundation

Xant

he E

lbric

k

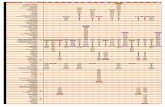

Hassan El-Amin Photo: Karen Almond

February 21 Malcolm X is assassinated in Harlem, New York at the Audubon Ballroom.

auGuST 6 The Voting Rights Act signed by Lyndon B. Johnson which illegalizes discriminatory voting requirements.

March 8 In Alabama, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. leads a march across the Pettus Bridge to Montgomery in support of voting rights and is met with a police blockade in Selma.

OcTOber 15 Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seales found the Black Panther Party in Oakland, California to improve housing, educational and employment conditions for African Americans.

aPrIL 18-23 Citizens of Baltimore begin to protest the mistreatment of Freddy Gray.

aPrIL 4 Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. is assassinated on the balcony of his hotel room at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee.

aPrIL 12 In Baltimore, Maryland Freddy Gray, age 25, is stopped, assaulted and arrested by the police. He dies one week after his arrest.

aPrIL 11 President Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act or Fair Housing Act which prohibits discrimination by sellers or renters of property.

Congress passes Civil Rights Restoration Act expanding the reach of non-discrimination laws.

Patrisse Cullors reposts a Facebook message with the hashtag #blacklivesmatter after the acquittal of Trayvon Martin’s murderer George Zimmerman, sparking a movement of protests around the US.

auGuST 9 Mike Brown, an unarmed 18-year-old, is killed by officer Darren Wilson after being pulled over and assaulted for “jaywalking.”

2015

2014

2012

1992

1988

1968

1966

1965

aPrIL 29-May 4 Race riots erupt in Los Angeles, California after four white police officers on trial for the beating of Rodney King are acquitted by a jury in court.

February 26 Trayvon Martin, age 17, is killed in Sanford, Florida by neighborhood watch member George Zimmerman.

Civil Rights Timeline

born Michael King, Jr. on January 15, 1929, was a

revolutionary Baptist minister and social activist in the

movement toward Civil Rights in America. Renamed Martin

Luther King, Jr. after his by his father Martin Luther King

Sr. in honor of German protestant religious leader Martin

Luther. Raised in the Ebenezer Baptist church in Atlanta,

Georgia, King followed suit of his grandfather and father’s

tenure of pastorship for the Ebenezer Baptist Church. As

a student King grew up in segregated schools in Georgia,

yet despite the odds King graduated from high school,

earning a B.A. in 1948 from Morehouse College and Ph.D

in systematic Theology. It was during this time that he met

his wife Coretta Scott. Throughout his time as pastor and

activist, King molded a movement through his activism

in race relations organizing black boycotts of segregated

bus lines in Montgomery, Alabama from 1955-56 and

organizing civil rights organizations such as the Southern

Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in 1957. King led

with the philosophy of nonviolent resistance which led to

his arrest on various occasions throughout the 1950s and

‘60s. One of his greatest feats was the successful 1963

March on Washington, which brought together more

than 200,000 people. It was there that King gave his

monumental “I Have a Dream” speech. King continued his

crusade for civil rights until 1968 when he was met with a

fatal assassination at the Lorraine Hotel after delivering his

iconic speech “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” in favor of the

Poor People’s Campaign and sanitation worker’s strike in

Memphis, Tennessee.

DR. MARTIN LuTHER KING, JR.,

In the last years of his life, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. began to broaden the focus of his crusade for civil rights. He sought not only racial justice,

but economic justice. He campaigned against war and against poverty. He stood up for the rights of women, laborers, and the LGBT community. And as

he expanded his reach, he began to lose mainstream support. Many of even his staunchest supporters felt that he should stay focused on civil rights,

and that his support for other causes was weakening the movement. But King continued, because he understood something that few others did. He

understood that “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” He understood that “all men are created equal” truly did mean “all.” He understood

the interrelatedness of all human struggles, and this could not have been more perfectly illustrated than it was at the Memphis Sanitation Workers’ Strike.

Because, as King marched in solidarity with the sanitation workers in what would become the last political action of his life, the people carried signs that

read, simply, “I am a man.”

“I am a man.” A very simple, seemingly obvious declaration.

But the meaning it carries, both political and historical,

is immense. Historically, the roots of “I am a man” as a

rallying cry came with the abolitionist movement in the

united States and South Africa in the late 1700s. In that

time period, men of color and slaves were referred to

as “boy,” a pejorative meant to demean and insult their

social status. In response, prominent abolitionist Josiah

Wedgwood began producing small medallions depicting

a black man in chains, encircled by the words, “Am I not

a man and a brother?” The question, “Am I not a man?”

became a popular refrain in the anti-slavery, and later

anti-discrimination movements, playing a popular role in

the infamous Dred Scott decision – the now unanimously

denounced Supreme Court ruling from 1857 that African

Americans, enslaved or free, could not be American

citizens. Decades later, as the Civil Rights Movement

began to pick up steam, “Am I not a man?” evolved into “I

am a man!” It was no longer time, it seemed, to wait for

answer – it was time to provide the answer that should

have been obvious all along.

But what made “I am a man!” such a powerful, revolutionary

statement? Because to oppress a people, to deny them

their fundamental rights, is – according to Dr. King, as well

as many scholars before and since – dehumanization. In

fact, in the united States’ own Constitution, written by the

From I am a Man! to Black Lives Matter Personhood as Resistance

founding fathers only two decades after they declared

that “all men are created equal,” slaves are described

as being worth “three fifths of all other persons.” This

article offers explicit, quantifiable dehumanization

– it declares in no uncertain terms that a slave is

only sixty percent human. Of course, this article of the

Constitution was eventually repealed as slavery was

made illegal, but the social and societal precedent

had been set. And when you consider the atrocities

that African Americans faced during and after slavery,

it’s easy to understand why America would want to

think of brown-skinned people as less than human:

because there was simply no other way to justify the “Where Do We Go From Here?” Address to the Southern Christian Leadership ConferenceAugust 16, 1967

I am somebody. I am a person. I am a man with dignity and honor. I have a rich and noble history, however painful a nd exploited that history has been.

PROTESTORS AT THE MEMPHIS SANITATION STRIKE, 1968.

by Laura Colleluori

February 21 Malcolm X is assassinated in Harlem, New York at the Audubon Ballroom.

auGuST 6 The Voting Rights Act signed by Lyndon B. Johnson which illegalizes discriminatory voting requirements.

March 8 In Alabama, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. leads a march across the Pettus Bridge to Montgomery in support of voting rights and is met with a police blockade in Selma.

OcTOber 15 Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seales found the Black Panther Party in Oakland, California to improve housing, educational and employment conditions for African Americans.

aPrIL 18-23 Citizens of Baltimore begin to protest the mistreatment of Freddy Gray.

aPrIL 4 Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. is assassinated on the balcony of his hotel room at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee.

aPrIL 12 In Baltimore, Maryland Freddy Gray, age 25, is stopped, assaulted and arrested by the police. He dies one week after his arrest.

aPrIL 11 President Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act or Fair Housing Act which prohibits discrimination by sellers or renters of property.

Congress passes Civil Rights Restoration Act expanding the reach of non-discrimination laws.

Patrisse Cullors reposts a Facebook message with the hashtag #blacklivesmatter after the acquittal of Trayvon Martin’s murderer George Zimmerman, sparking a movement of protests around the US.

auGuST 9 Mike Brown, an unarmed 18-year-old, is killed by officer Darren Wilson after being pulled over and assaulted for “jaywalking.”

2015

2014

2012

1992

1988

1968

1966

1965

aPrIL 29-May 4 Race riots erupt in Los Angeles, California after four white police officers on trial for the beating of Rodney King are acquitted by a jury in court.

February 26 Trayvon Martin, age 17, is killed in Sanford, Florida by neighborhood watch member George Zimmerman.

Civil Rights Timeline

born Michael King, Jr. on January 15, 1929, was a

revolutionary Baptist minister and social activist in the

movement toward Civil Rights in America. Renamed Martin

Luther King, Jr. after his by his father Martin Luther King

Sr. in honor of German protestant religious leader Martin

Luther. Raised in the Ebenezer Baptist church in Atlanta,

Georgia, King followed suit of his grandfather and father’s

tenure of pastorship for the Ebenezer Baptist Church. As

a student King grew up in segregated schools in Georgia,

yet despite the odds King graduated from high school,

earning a B.A. in 1948 from Morehouse College and Ph.D

in systematic Theology. It was during this time that he met

his wife Coretta Scott. Throughout his time as pastor and

activist, King molded a movement through his activism

in race relations organizing black boycotts of segregated

bus lines in Montgomery, Alabama from 1955-56 and

organizing civil rights organizations such as the Southern

Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in 1957. King led

with the philosophy of nonviolent resistance which led to

his arrest on various occasions throughout the 1950s and

‘60s. One of his greatest feats was the successful 1963

March on Washington, which brought together more

than 200,000 people. It was there that King gave his

monumental “I Have a Dream” speech. King continued his

crusade for civil rights until 1968 when he was met with a

fatal assassination at the Lorraine Hotel after delivering his

iconic speech “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” in favor of the

Poor People’s Campaign and sanitation worker’s strike in

Memphis, Tennessee.

DR. MARTIN LuTHER KING, JR.,

In the last years of his life, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. began to broaden the focus of his crusade for civil rights. He sought not only racial justice,

but economic justice. He campaigned against war and against poverty. He stood up for the rights of women, laborers, and the LGBT community. And as

he expanded his reach, he began to lose mainstream support. Many of even his staunchest supporters felt that he should stay focused on civil rights,

and that his support for other causes was weakening the movement. But King continued, because he understood something that few others did. He

understood that “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” He understood that “all men are created equal” truly did mean “all.” He understood

the interrelatedness of all human struggles, and this could not have been more perfectly illustrated than it was at the Memphis Sanitation Workers’ Strike.

Because, as King marched in solidarity with the sanitation workers in what would become the last political action of his life, the people carried signs that

read, simply, “I am a man.”

“I am a man.” A very simple, seemingly obvious declaration.

But the meaning it carries, both political and historical,

is immense. Historically, the roots of “I am a man” as a

rallying cry came with the abolitionist movement in the

united States and South Africa in the late 1700s. In that

time period, men of color and slaves were referred to

as “boy,” a pejorative meant to demean and insult their

social status. In response, prominent abolitionist Josiah

Wedgwood began producing small medallions depicting

a black man in chains, encircled by the words, “Am I not

a man and a brother?” The question, “Am I not a man?”

became a popular refrain in the anti-slavery, and later

anti-discrimination movements, playing a popular role in

the infamous Dred Scott decision – the now unanimously

denounced Supreme Court ruling from 1857 that African

Americans, enslaved or free, could not be American

citizens. Decades later, as the Civil Rights Movement

began to pick up steam, “Am I not a man?” evolved into “I

am a man!” It was no longer time, it seemed, to wait for

answer – it was time to provide the answer that should

have been obvious all along.

But what made “I am a man!” such a powerful, revolutionary

statement? Because to oppress a people, to deny them

their fundamental rights, is – according to Dr. King, as well

as many scholars before and since – dehumanization. In

fact, in the united States’ own Constitution, written by the

From I am a Man! to Black Lives Matter Personhood as Resistance

founding fathers only two decades after they declared

that “all men are created equal,” slaves are described

as being worth “three fifths of all other persons.” This

article offers explicit, quantifiable dehumanization

– it declares in no uncertain terms that a slave is

only sixty percent human. Of course, this article of the

Constitution was eventually repealed as slavery was

made illegal, but the social and societal precedent

had been set. And when you consider the atrocities

that African Americans faced during and after slavery,

it’s easy to understand why America would want to

think of brown-skinned people as less than human:

because there was simply no other way to justify the “Where Do We Go From Here?” Address to the Southern Christian Leadership ConferenceAugust 16, 1967

I am somebody. I am a person. I am a man with dignity and honor. I have a rich and noble history, however painful and exploited that history has been.

PROTESTORS AT THE MEMPHIS SANITATION STRIKE, 1968.

by Laura Colleluori

Dallas Theater Center

This riveting play by American playwright Katori Hall takes place on April 3, 1968–the eve of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s death at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. The play itself is a fictional set of events between King and a mysterious hotel maid named Camae after the delivery of his memorable speech “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” during the sanitation worker’s strike. Throughout the play King is forced to reconcile with his own fears, temptations and conviction, and the impact of these on the future of his people.

the StudyGuide 20152016Season

Well, I don’t know what will happen now. We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it doesn’t

matter with me now. Because I’ve been to the mountaintop. And I don’t mind. Like any man, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its

place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go

up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the promised land. I may not get there with

you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people will get to the promised land.”

“I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” April 3, 1968

Memphis, Tennessee

by KATORI HALL • directed by AKIN BABATUNDEOnstage thru November 11 Wyly Theatre / Studio TheatreAT&T Performing Arts Center

“Our aim must never be to defeat or humiliate the white man, but to win his friendship and understanding. We must come to see that the end we seek is a society at peace with itself, a society that can live with its conscience. And that will be a day not of the white man, not of the black man. That will be the day of man as man.”

“Our God Is Marching On”March 25, 1965Selma, Alabama

From I am a Man! to Black Lives Matter Personhood as Resistance

(continued)

horrible things that were being done to them. To treat a human that way would

be unforgivable. But if someone was not human, or was subhuman, it wouldn’t

matter as much, right?

Slaves in America were taken from their homes, were separated from their

families, were sold to owners and were treated as their property. They were

denied so many things that we associate with being human – homes, families,

often even names – that many slaves began to believe and accept that there was

no way out. However, many refused to accept this attempt at dehumanization.

Oral histories and storytelling became vital in enslaved communities as a

reminder of their humanity – their past and hopeful future. Spirituals calling

upon God and acknowledging the existence of their souls were sung out in

the fields to help people persevere through hard labor. Any small word or

action that reinforced their humanity became an act of resistance. For another

example of the preservation of humanity as resistance, we could also look at

the prisoners living in concentration camps during the Holocaust. They were

stripped of their names and given numbers, they were stripped of their clothes

and given uniforms – all of their identifying features were taken away from

them. But, as Holocaust survivor and author Primo Levi recalls, even in such a

dire situation, prisoners found small ways to reclaim their humanity. He writes:

“We are slaves, deprived of every right, exposed to every insult, condemned

to certain death, but we still possess one power, and we must defend it with

all our strength for it is the last - the power to refuse our consent. So we must

certainly wash our faces without soap in dirty water and dry ourselves on our

jackets. We must polish our shoes, not because the regulation states it, but for

dignity and propriety. We must walk erect, without dragging our feet, not in

homage to Prussian discipline but to remain alive, not to begin to die.”

Asserting your own humanity, your own personhood, has therefore always

been an act of resistance against an oppressive system. To claim your own

individuality is to refuse to consent to the deprivation of your rights. Even

today, we hear echoes of “I am a man!” in a newly popular slogan, “Black lives

matter!” The wording is different, and the means of spreading the message –

from engraved coins in the 1700s to hashtags in the 2000s – have certainly

evolved, but across centuries, continents, and causes, the message is universal:

I am a person. I have dignity. I have a life that is equal to yours, and it matters.

is an African American playwright, journalist,

and actress from Memphis, Tennessee. Her play

Mountaintop was first produced in London in June

of 2009 and won the Olivier Award for Best New

Play in 2010. Her other plays include Hurt Village,

Hoodoo Love, Remembrance, Saturday night/Sunday

Morning, and the Hope Well. Hall has won numerous awards including the

2005 Lorraine Hansberry Playwriting Award, 2006 New York Foundation of the

Arts Fellowship in Playwriting and Screenwriting and the 2007 Fellowship of

Southern Writers Bryan Family Award in Drama.

“Are my words enough for the revolution?”

I didn’t know what revolution I wanted

to be part of, but I asked myself

this nonetheless. I’m not very

religious but I think of the

theatre as a church: it’s my

salvation in the way that I can

move people to tears

or to laughter.

That’s the first

step towards

social change:

when we see

one another in

our darkness and

our light.”

Katori Hall

-Katori Hall, 2011 katorihall.com

PIER 1 ImPORTs NEImAN mARcUs Ernst & Young LLP ExxonMobil National Corporate Theatre Fund t. howard + associates Theodore & Beulah Beasley Foundation

Xant

he E

lbric

k

Hassan El-Amin Photo: Karen Almond