Asokan Pillars III

-

Upload

anonymous-r844tz -

Category

Documents

-

view

223 -

download

1

Transcript of Asokan Pillars III

-

7/28/2019 Asokan Pillars III

1/14

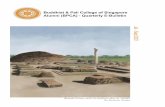

'Aokan' Pillars: A Re-Assessment of the Evidence - III: CapitalsAuthor(s): John IrwinReviewed work(s):Source: The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 117, No. 871 (Oct., 1975), pp. 631-643Published by: The Burlington Magazine Publications Ltd.Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/878154 .

Accessed: 28/03/2012 19:21

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

The Burlington Magazine Publications Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access

to The Burlington Magazine.

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=bmplhttp://www.jstor.org/stable/878154?origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/stable/878154?origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=bmpl -

7/28/2019 Asokan Pillars III

2/14

T H E BURLINGTON MAGAZINE NUMBER871 . VOLUMECXVII . OCTOBER1975JOHN IRWIN

' A A o k a n ' P i l l a r s : A Re-assessment o f t h e EvidenceI I I : C a p i t a l s

IN the previous article' we found evidence to confirm thatASoka was not the erector of all the pillars traditionallynamed after him. Out of a total of fifteen pillar-remains nowsurviving, nine were placed within a firm chronologicalframework consisting of two groupings.EARLY (PRE-ASOKAN) GROUP

Rcmpurvo ull nis usambi oi

These pillars had apparently been erected without founda-tion stones, following practice earlier used for wooden-shafted pillars of similar dimensions. Since this method wastechnically inadequate for stone monuments founded in thewaterlogged, sedimentary subsoils of the Ganges basin, theyhad all either sunk into the ground or collapsed completelywithin a few centuries of erection. None is known to haveborne an Adokan inscription or to have had any provableassociation with Adoka. Of the surviving emblems, two areIndian animals carved in native Indian style; the third is alion carved in foreign, heraldic style, yet clearly the earliestof surviving Indian lion-capitals.LATER GROUP

Ski Rmito,baw Topra Lour'yQ&dnSo,5arh opraLo OF-

These were erected on foundation stones substantialenough to overcome the problem of sinkage. All are inscribedwith Aboka's edicts. In three cases out of five there is someindependent, corroborative evidence of association with

Agoka. Surviving emblems are all lions carved in foreign,heraldic style.Continuing from this point, we shall now begin re-examin-ation of the capitals. The term 'capital' is used here to meanthe whole crowning composition which has three mainconstituents: 'bell', 'abacus', and emblem. The first twoterms are employed conventionally: their true nature andmeaning is to be discussed in this article.First, we have to consider what kind of model or prototypemight have inspired the carvers of the first stone capitals.Nobody would expect such a mature and sophisticated styleof sculpture to have emerged suddenly, out of an artisticvacuum. Obviously there were precedents - but what kind?The answer favoured over the last hundred years is thatthe prototype was foreign and that the style was broughtto India by Perso-Hellenistic craftsmen - a hypothesis neverproved and one we have now rejected as obsolete.The only alternative so far advanced is that the carversof the first stone capitals were following prototypes in wood,which have long since disappeared. But in our opinion, thistheory is no more convincing than the first one. Althoughwe are in no doubt that the first stone pillars were precededon Indian soil by pillars with shafts of wood,2 the assumptionthat their capitalswere also carved in wood is another matter.Indeed, we regard this as improbable.The earliest surviving stone capitals we now know toinclude the SankisS elephant (Fig.2) and the Ramptirvabull (Fig.3). These also happen to be the largest of allsurviving 'Abokan' pillars.3 Can we imagine them havinghad wooden prototypes? The idea is not inconceivable. Thesculptor would have had to start with the bole of a very largetree; but hardwood trees of this size do grow in India, andin the first millennium B.C. there must have been manymore of them. The idea becomes more difficult to acceptwhen one tries to imagine a wooden sculpture of thesedimensions exposed to the extremes of a monsoon climate.Under the rapidly alternating conditions of wetting anddrying out under high temperature, the bole would certainlyhave split, with disastrous aesthetic effect. No protectiveresin known even to modern science could have prevented

1The first two articles in this series were published in THE BURLINGTONMAGAZINE, Vol. CXV [November, 19731, PP.7o6-2o, and Vol. CXVI [Decem-ber, 19741, PP-712-27. The next and final one (Part IV) will appear next yearunder the title 'Symbolism', drawing together the evidence presented in thefirstthree articles and offering a comprehensive view of the history and meaningof the pillars. The series is condensed from the 1974 Lowell Institute Lecturesgiven at Boston, Massachusetts, the present article being based on the sixthlecture. Once again I am greatly indebted to Miss Margaret Hall for thedrawings published with this article and for her perceptive advice on manymatters concerning the history of ornament.

2 In the previous article, we found positive evidence at Sanchi to support thisconclusion (THEBURLINGTONMAGAZINE, ol. CXVI [December, 1974], PP-725-26). The view that the first stone capitals were copied from wooden proto-types was strongly held by A. K. COOMARASWAMY,ut he stated his opiniononly in rhetorical terms, without attempting to prove it. For instance, in 1930he wrote: 'Can anybody seriously doubt that wooden "bell" capitals . .existed in India before the time of Asoka?' Quoted from 'Indian sculpture:a review', Rupam, Calcutta, Nos. 43-44 [1930], P.3-3 Contrary to what might have been expected, the stone pillars known to havebeen erected by Asoka were smaller than the elephant and bull pillars we nowknow to be pre-Asokan. The Sirnith pillar, which is the most famous andprobably the last Agoka erected, was the smallest of them all.631

-

7/28/2019 Asokan Pillars III

3/14

'ASOKAN' PILLARS : A RE-ASSESSMENT OF THE EVIDENCE - III : CAPITALS

A. Tree bole, showing splits at theperiphery.

this happening.4 Splittingproceeds from an inescapablescientific law whereby therate of peripheral shrinkageof a bole is always abouttwice that of radial shrink-age, producing familiar vis-ual results (Fig. A). So thatthe effect of climate wouldmerely have been to acceler-ate and exacerbate an al-ready inevitable process. Abole once sculpted, withmany re-entrants, would beeven more vulnerable, and thus allow easy entry for thespores with which the Indian monsoon air is notoriouslyladen. On these grounds - and bearing in mind that works ofart of this aesthetic genre were obviously required to endure -we believe that the theory of the wooden prototype isimplausible, and ultimately untenable.What, then, is the true explanation? The hypothesis we

have to offer is that the prototype of the so-called 'Adokan'pillar had only its shaft made of wood, and that the crowningemblem was fashioned in copper,5probably gilded. Thishypothesis, we believe, is the only one which stands up totest, and the surprising thing is that nobody seems to havethought of it before.In the first place we know that India was rich in copperin the first millennium B.C.,6 and that Indian craftsmenwere renowned for their skill in working it.' Strabo, forinstance, on the authority of Megasthenes (who was residentas Greek ambassador to the Mauryan court before Adoka'sreign), described how Indians fashioned in copper (IvaLxoXoxoo)8 huge vessels and other paraphernalia for religiousritual, including tables, high chairs, drinking-cups andbath-tubs.Still more relevant, we learn from early Buddhist textsthat pillars with copper animals on top were erected in frontof stiipas. One of these is the Chinese translation of theSarvdstivddin Vinaya-pitaka which no longer survives inits original Indian language. It was quoted in our firstarticle.9 The Buddha, having been asked by a disciple if itwas permissible to erect lion-pillars in front of stiipas andgiven sanction, was next asked if he would allow the crowning

lions to be fashioned in copper, to which he also assented.Another Chinese translation of a lost Indian text, theMahi-sdsaka Vinaya-pitaka, gives directions that in front ofstuipasshould be erected 'pillars of copper, iron, stone orwood', and that their emblems should consist of 'elephants,lions, and other animals'.1oNo such copper capitals survive in the Ganges basin to-day; but that is hardly to be expected, since gilt-copperimages would have been obvious targets for the iconoclastand looter, especially when associated with sacred pillars.But as soon as one moves away from the trunk-routes ofIslamic invasion - either northwards into the foothills ofthe Himalayas, or southwards towards the tip of the Indianpeninsular - many sacred pillars with copper emblems arefound to survive, some of them of the same size as and evenlarger than some 'Abokan' pillars. At Figs.Io and II wereproduce two in Nepal, which we could match with othersas far West as Chamba, and as far south as Travancore."Although these capitals are medieval or later, as one wouldexpect in such outlying locations, we believe that they repre-sent the continuation of a practice of erecting pillars withgilt-copper emblems which had been established in theGanges basin - the heartland of Indian religion and culture -long before the reign of Asoka. We would further suggestthat many of the shafts of the sacred pillars which havestood topless in northern India at least since the fourteenthcentury A.D. had once been crowned with gilt-copperemblems.A case in point is the famous iron pillar standing in theshadow of the Kutb Minar at Merauli, near Delhi, well-known to every tourist, and reproduced here at Fig.6. Itsinscription proves it to be a pillar of the Gupta period(third to fourth century A.D.) which had been looted froman unknown temple, and that it originally had on top animage of the sun-bird Garuda, assimilated into the Hindupantheon at a relatively late date as carrier of the godVishnu. Strange to say, none of the scholars who havewritten at length on this pillar has paused to consider howthe Garuda emblem might have been fashioned.12 Nobody,surely, would suppose that the emblem had been cast iniron like the shaft? In our opinion, this, and many otheremblems of shafts now standing topless in northern India,were probably made of gilt-copper.13

4 I am advised by Norman Brommelle, Keeper of Conservation Department,Victoria and Albert Museum, that the most efficient protective known evento-day is bitumen. This had been used at Mohenjo-daro, about 2,ooo B.C., forsealing the brickwork of the Great Bath. For obvious reasons, it is unlikely tohave been used at any period for protecting sculptural works of art. To the bestof our knowledge there has so far been no systematic analysis of surviving frag-ments of ancient Indian woodwork to determine what preservatives had beenused.5The metal is unlikely to have been pure. It was probably an amalgam con-sisting mainly of copper but including small quantities of gold, silver, tin andlead, prescribed according to religious formula, like the panchaloha r five-metalamalgam described in medieval texts.6 D. D. KOSAMBI: Theculture and civilisationof ancient India, London [19651],P59and pp.89-9o; also map showing distribution of ores at pp.98-99.7 We have already noted the precision with which the copper dowel securinglion-capital to shaft at Rimpiirvi was made (THE BURLINGTON MAGAZINE,Vol. CXV [November, I9731, p.713).8 STRABO: Geography, 15.1.69.9 THE BURLINGTON MAGAZINE, Vol. CXV [November, 1973], p.716.

10 Quoted from ANDRgBAREAU;La construction et le culte des stiipa d'apres lesVinayapitaka', Bulletin de l'tcolefranfaise d'extrime-orient,ome L [1962], p.239.In this important article, Prof. Bareau claims that these texts are the earliestsurviving canonical works dealing with the construction of the stGpa,apartfrom the Mahdparinirvdnasutra.lthough it is unlikely that they were translatedinto Chinese before about the beginning of the fifth century A.D., they mustundoubtedly have already been ancient texts when brought to China. In aletter to the author dated I5th March, 1975, Prof. Bareau expressesconfidentlythe opinion that the evidence of the two Chinese translations is valid at leastfor the first century B.C., and 'probably earlier'.11 An interesting South Indian parallel is the 5o-ft. pillar with stone shaft andgilt-copper emblem of Garuda which stands in the compound of the Maha-vishnu temple at Tiruvalla, near Travancore. See V. RAGHAVAN NAMBYAR:'Annals and antiquities of Tiruvalla', Kerala SocietyPapers, series 2 [1929],pp.68-69, with plate.12 The best general description of this pillar was written by j. P. VOGEL: 'Factsand fancies about the iron pillar of Old-Delhi', Journal of PunjabHistoricalSociety,Vol. IX, Part I [19231, PP-71-91.13Among topless shafts surviving today which may originally have had copperemblems are the famous Heliodorus pillar at Besnagar, erected by the ambas-632

-

7/28/2019 Asokan Pillars III

4/14

2. The SankisdElephant-capital.olish-ed sandstone. Photo: India OfficeLibrary.3. The RdmpirvdBull-capital.Polished Sandstone. 4. The Vaiidlf Lion-capital.Sand-stone. Photo: Elinor Gadon. 5.

6. 7.

8.

6. TheKutb ronPillar,near Delhi. c.fourthcentury A.D.7. Base-drum (or 'bell') of Achaemenian column atPersepolis. AfterE. F. Schmidt.8. Underside of Sankisd Elephant-capital (Fig.2above). Photo: Dr Joanna Williams.9. Bell of a Gupta pillar at Sondini, Mandasor, fifthcentury A.D.So. Gilt-copper lion on pillar, Telleju temple, Nepal,c.sixteenth century A.D. Photo: RobertSkelton.

I I. Gilt copper Garuda on pillar at Bhadgaon, Nepal,medieval. Photo:Dr John Marr.9.

-

7/28/2019 Asokan Pillars III

5/14

12.

12. TheSdrndthCapital.Polished sandstone.13-16. Close-ups of the four quadrupeds on the abacus of theSfrnmth Capital.17. Painting of lotus-plant, by an unknown Indian artist,eighteenth century. Photo: British Museum of JaturalHistory.18. Wooden chariot-wheel excavated in precincts of Aioka'scapital city, Pitaliputra (modern Patna). Now in PatnaMuseum.

I3. 14-

15. 16.

I7. I8.

-

7/28/2019 Asokan Pillars III

6/14

'ASOKAN' PILLARS: A RE-ASSESSMENT OF THE EVIDENCE - III. CAPITALSOn the hypothesisthat the prototypesof 'Abokan'pillarshadcopperemblems,much more aboutthe originand historyof these monuments begins to fall into place. For instance,it providesa clue to the origin and meaning of the so-called'AMokan ell', which some prefer to call the 'Persepolitanbell', and others 'lotus-capital'. We believe that all theseterms are wrong and misleading.Taking first the term 'Persepolitanbell', this implies thatthe Indians derived their bell from Achaemenid art. Aspointed out in the previous article, the only pillars atPersepolisare load-bearingAtructural olumns of the build-ings, different in function to the free-standingvotive pillarsof India.14The capitalsof these columns (Fig. L) are elabor-ate structures composed of several members, supportingrichly-carved brackets in the form of addorsed animals orlegendary beasts such as the man-bull depicted here. Theword 'bell' has been loosely applied to two quite differentparts of the Persepolitancolumn. One appears at the top,marking the junction between shaft and capital (Fig. L),and is composedofwhat Frankfortand othershave describedas 'long, drooping sepals' rather than 'petals'. (This type ofbell bears so little resemblance to a lotus-flower that itcould hardly be considered as prototype of the 'AMokanbell'.) The otherone appearsat the base (Fig.7) and wouldbe more accuratelydescribedas 'drum' than 'bell', its formand function deriving from the stone base-drumson whichwooden columns were traditionally set in Western Asia.'5The decorationof this particularmemberis unquestionablylike an 'invertedlotus-flower',and scholars who have statedthe case for the Persepolitanorigin of the 'Agokanbell' havealways cited this one as the prototype.16 Both functionallyand aesthetically, however, the Persepolitan base-drum is

different. In the first place, it is intended to harmonise thejunction between shaft and ground. The low-relief fluting ofits sharply-ridged and inverted lotus-petals serves as acontinuation of the fluting on the shaft itself; 'AMokan'pillars, on the other hand, were always plain and, as notedin the first article," they were designed to stem nakedly outof the ground without bases of any kind. (We shall returnto this aspect, and its symbolic significance, in the finalarticle.)The next point to note is that the Persepolitan base-drum,although very clearly an inverted lotus-flower, is not basedon the Indian lotus or padma, which botanists call Nelumbonucifera.s8 It is the Egyptian species Nymphaea stellata,19which at this period was unknown in India.20 The verydifferent appearance of the two species is illustrated in thedrawing at Fig. B.

Del-oil From wolpoi:,i, inM1,eTombFSenunulem' eumboNymphoea (/9/-Dnos y)B. Left, the Indian lotus (NelumbonuciJera).entre, the Egyptian lotus (Nympheastellata).Right, the Egyptian lotus as conventionalized in Egyptian art.

A final point to note is that the 'Agokan'bell is differentin size as well as shape from the Persepolitan, the contrastbeing demonstrated by the superimposed drawing at

VASALI LAUR/YA-NANDANGARH

RAMPURVAULL SARNATHC. The bells of the VaiiMli, Lauriyi-Nandangarh, Rampfirvi Bull andSSrn~th capitals superimposed upon the Persepolitan base-bell.

sador of an Indo-Greek king to the local court in the second century B.C. (seemy article, 'The Heliodorus pillar: a freshappraisal', AARP (Art and Archaeo-logy Research Papers), No. 6 [I974], due to be republished in expanded formin Purdtattva Bulletin of Indian Archaeological Society, New Delhi, No. 7).Similar claims could perhaps be made for two very fine medieval pillars inOrissa: one at Jajpur (JAMES FERGUSSON: Historyof IndianandEasternArchitecture,London [1876], Vol. I, p.I I I and Fig.32I1); the other, now standing in front ofthe Jagganath temple at Puri with an absurdly out-of-scale image of Hanumanon top, originally stood before the sun temple at Konarak with an image ofAruna, the sun-god's charioteer, now missing (see w. w. HUNTER: Orissa andits remains.Vol.I, London [1872], p.290, for a drawing of the pillar as it standsto-day; and ALICEBONERand SADASIVA RATH SARMA:New light on the Sun Templeat Konarak, Varanasi [1972] pp.121-22 and 235, for evidence of its originalsetting at Konarak).14 For purposes of this article, we shall henceforth use the term 'column'for describing a load-bearing structure, and 'pillar' for a free-standing one.16At Persepolis there survive some remains of wooden shafts used as weight-bearing columns in conjunction with stone base-drums of the type we arediscussing. See ERICH F. SCHMIDT: Persepolis , Oriental Institute PublicationsNo. LXVIII, University of Chicago [1953], Plate 191 a & b, and plate 192a & b. This combination of wooden shaft and stone base seems to have beencharacteristic of minor buildings such as palace harems.16 We shall be returning to discussion of the upper bell of Persepolitan columnsat a later stage of this article. Here we are only concerned with the lower bellwhich is alone specified by scholars claiming Persepolitan origin of the 'Asokanbell'. James Fergusson was probably the first: 'The capitals of Asokan pillarsare so similar to the lower members of those at Persepolis, and more especiallyto the bases of the columns there, as to leave no doubt of their common origin'.J. FERGUSSON: IllustratedHandbookof Architecture, ol. I, London [1876], P.7.A. K. Mitra was even more emphatic: 'The Mauryan architect must have, bya bold stroke of imagination, transferred the Persian base to the top of hisshaft'. A. K. MITRA: 'Mauryan art', Indian Historical Quarterly, Vol. 3 [1927],p.545. The Achaemenid bell published by Mitra at Fig. I of his article isfrom Susa and not Persepolis.

17 THE BURLINGTON MAGAZINE, Vol. CXV [November, 1973], p.720. The only'Asokan' pillar standing to-day as it was originally intended to be seen - risingstraight out of the earth without any kind of plinth - is the topless shaft atKosam, reproduced in THE BURLINGTON MAGAZINE, Vol. CXVI [December,i974], Fig. 15. The chance reason for its survival without plinth is explainedat p.723 of that article.18sThe species is also known as NelumbiumpeciosumWilld.). There was someduplication in the nomenclature of oriental plants in the eighteenth andnineteenth centuries, as botanists were working independently in differentterritories.19Both the Indian and Egyptian plants belong to the same family Nymphaeaceae,which includes as its genera Nymphaea,Euryaleand Nelumbo.20 Information provided by Dr Vivi Tickholm (co-author of Flora of Egypt)of Cairo University, in personal letter dated 3ist January, 1975.

635

-

7/28/2019 Asokan Pillars III

7/14

'ASOKAN' PILLARS : A RE-ASSESSMENT OF THE EVIDENCE - III : CAPITALSFig. C.21 The full significance of these dissimilarities willbecome apparent presently. The point to be stressed at thisstage is that they have hitherto been ignored by those arguinga Persepolitan origin for the 'Adokan bell'.We shall now lean the other way and focus on whateversimilarities exist between the Indian and Iranian bells. Oneis the way in which individual 'petals' are ridged down thecentre and edged with cable-moulding. Another is theappearance of the peeping tips of secondary petals betweenthe main ones. Both features are clearly illustrated in thedrawing of the 'Adokan bell' at Fig. D. Are they enough tocounter-balance the differences of form and structure, andthus to keep open the case for the Persepolitan origin of the'AMokan'bell? Before trying to answer, we must extend

D. The Asokan form of bell-pendants.

the picture further.We have already recog-nised that the Persepolitanbell is based on the Egyptianlotus. We shall see now thatEgypt is also the source ofthe artistic conventions weare discussing, including theridging of the petals whichhappens to be a feature of theEgyptian flower itself. Thedrawing at Fig. B, centre,shows the Egyptian flower asdepicted by botanical artists trained in European post-Renaissance tradition - in other words, in three-quarter view.Artists of ancient Egypt, on the other hand, not having beentrained to draw in perspective, rendered the flower in strictprofile (Fig. B, right) Comparing the two versions one cansee at a glance how the 'peeping-petal' convention origi-nated.The next question to consider is how this convention

might have been transmitted from Egypt to Iran, and alsohow it reached India. Was Achaemenian art the only - oreven the main - intermediary between Egypt and India?The Iranians, we know, assimilated Egyptian conventionsin two quite separate ways: (I) direct from Egypt afterconquest by Cambyses in 525 B.C., when Egyptian craftsmenare known to have been brought back to Iran;22 and (2) viathe arts of the Levant and Asia Minor, where Egyptianinfluences had been assimilated from a much earlier period. 23Of these two channels, the latter seems to have been themore important, notwithstanding the fact that the antece-dents and early history of Achaemenian art are still obscure.(Henri Frankfort has attributed this obscurity to earlier useof perishable materials. He saw the Achaemenian and the

Ionian columns as parallel Asian developments of theEgyptian plant column - not as it was carved in stone, but inwood and gesso.)24In this context, it is no surprise to learn that the 'peeping-petal' convention had been naturalised in Asia Minor (inthe form of the so-called 'leaf-and-dart' motif) before anyof the Achaemenian cities had been built. At Fig. F i wesee this motif on a column of the archaic Ionian temple ofArtemis at Epheseus, dated about 550 B.C. At Fig. F ii wesee the same motif absorbed into Greek art some twenty-fiveyears later, when it is used as ornament on the type ofarchitectural moulding known as the kumation.25 We arenow on the Greek mainland, at Delphi, at the peak of the'Orientalising Phase' of archaic Greek art, centuries beforeAgoka was born. Note, too, that this motif was absorbed intoGreek art with two other West Asian motifs - the so-called'lotus-and-palmette' and the 'bead-and-reel', which occurin exactly the same combination on the abacus of the'Adokan' pillar at Allahdbid (Fig. E ii). As we shall even-tually learn, this is not proof of Greek influence in India.Rather, it is evidence that in the middle of the first millen-nium B.C., Greece, Iran and India were all peripheral cul-tures borrowing from the same West Asian source - moreparticularly, from that region which was constituted byAssyria, the Levant, and Ionia. A further point of particularsignificance to us, as we shall presently recognise, is thatartists of Greece, Iran and India employed these sameborrowed motifs in a spirit totally alien to each other.So up to this point there is nothing of substance to supportthe idea that the Achaemenians were the only intermediariesof Egyptian influence in India. This is therefore the momentto look at the problem afresh, uncommitted to any previoustheory.Did the carvers of 'Adokan' pillars derive the idea of theirbell from Persepolis, or not? So far, only one scholar, thelate A. K. Coomaraswamy, has argued in the negative.26 Healone tried to prove that Indian artists had arrived inde-pendently at their form of bell. The logic of his argument,however, was weak. Selecting some rather untypical detailsof lotus treatment in stone-reliefs at Bharhut (reproduced

21 Not all Persepolitan bells had steep vertical sides; some were designed toslope. The particular point to be stressed in this context is that none hadbulging outlines like the Indian ones.22This is proved by the famous Susa building inscription composed in thename of Darius I (522-846 B.C.), a translation of which is published byHENRI FRANKFORT, Op.cit., p.349.23 Egyptian art seems to have exerted its most formative influence in WesternAsia in the fourteenth century B.C., coinciding with the military expeditionof the Pharoahs in Syria. For an interesting discussion of reciprocal Egyptian-Asiatic influences, see HELUNE DANTHINE:Le Palmier-datier t les Arbressacres,Haut-commissariat de la R6publique frangaise en Syrie et au Liban, Biblio-thbque archlologique et historique, tome XXV, Paris [1937], esp. Vol. I,chapter VI.

24 'The Achaemenian column is the most elaborate one known in ancientarchitecture, but it is demonstrably a branch of the eastern Mediterraneandevelopment which led, in Greece, to the Ionian column. The starting-pointof the whole series is the Egyptian plant column, not as it was carved in stone,but in the more extravagant form of wood and gesso, which was used injoinery for temporary shrines, kiosks, and other light structures'. HENRI FRANK-FORT, in a review of E. F. Schmidt's Persepolis , Journalof Near EasternStudies,Vol. XIV 119551, p.61-62.25Kyma(Greek), cyma(Latin) means 'a wave', and kumation Latin cymatium)is a cornice of double-curved section (see Fig. F ii). The etymology is revealingand highly relevant to our theory that the 'honeysuckle' reached India as amagical symbol of fertility, as will be seen presently. T6 xugttLov is the diminu-tive of T6 xgca which, according to H. D. LIDDELL'SEnglish-Greek Lexicon,means 'anything swollen as if pregnant'.26 A. K. COOMARASWAMY: 'Origin of the Lotus- (so-called Bell-) Capital',Indian Historical Quarterly, Vol. 6 [1930], pp.372-75. V. S. Agrawala followedCoomaraswamy in refusing to accept the 'Asokan bell' as anything but Indian,but he presented his case as an article of faith, making no attempt to prove it.He saw the bell as an inverted lotus-flower 'overflowing' the formof a symbolicvase-of-plenty (pirna-ghata). v. S. AGRAWALA: The Wheel Flag of India: Chakra-dhvaja,Varanasi [19641, PP-24 ff.; and Indianart, Varanasi [1965], pp.103 ff.For independent mythological support of the idea of the 'bell' as an invertedvase, see F. B. J. KUIPER:'The heavenly bucket', IndiaMaior (CongratulatoryVolume presented to ProfJ. Gonda), Leiden [1972], p.152.

636

-

7/28/2019 Asokan Pillars III

8/14

'ASOKAN' PILLARS : A RE-ASSESSMENT OF THE EVIDENCE - III : CAPITALS

. 14-i. SANK ISA

h:ALLANABAD

iii RAM4PURVA BULL

.................... " . -..- ''

?I ' ~I~- -M?-71V "--~"~"-'~i~-~

v. SANSIT

v U L

i ;: ALAHY

E. The abacuses of the Mauryan capitals: (i) Sankisa; (ii) Allahaibid; (iii)Rdmpfirva Bull; (iv) Basti; (v) SAnchi; (vi) Lauriyfi-Nandangarh; (vii)Rfmpfirvd Lion.

Ovolo moulding ond ornament

Cyma Recta moulding, wi/hanthemion ornamenf andos/roaol moulding be/ow

Cyma Reversa moul//nq, wi/hY/eof-and- dart' ornomen/Base oF a Column (resoreV), From he ii Mouldinrs and ornameqtr oF Greekorchoic Temp/e oFAr/emis, Ephesus.S50B.C. archil-ec7ure.The kyma (Loin cymo) isusual/y a Frieze, or a cornice (c4?maihum)

itiOvo/o ornament, wi/th os-roqloornaomen/ iv Early Greek an/hemion, w/hbos/roaa/bel/owTheSi hon Treasury,De/ph. be/ow. TheSi)hnian Treasur0,De i6f/h century .C. 6?-h century B.C.

v. Ma/ure Greek an/hem/on. Sculp/ured FriezeFrom henorMhor/co of (SecfHon)the Erech/he;on, A hens- 420 -393 B.C.

vi.The EIypion Lotus anLily - typical vi The Assyrian 'knop-an-flower.'

Fromconventional Forms a Frogmeni- oF Fresco(restored)"

V'i /Ivory From NVmrud Assvrian, Found ix.Acaoemenid an/hem;on. Decora-rion,A' .Pplace of Esorhdoson. onomphora From Duvan il(680-669.C) The Brihsh Museum Si/ver-9'14 chased Early 5/h cenluvyB.CF. Sources of the 'Anthemion' ornament on the Mauryan capitals. (i) Ephesus,'Leaf-and-dart' on column; (ii) Mouldings from Greek classical orders ofarchitecture, with their normal ornament; (iii) Ovolo ornament, Delphi;(iv) Early Greek anthemion, Delphi; (v) Mature Greek anthemion, theErechtheion, Athens; (vi) The Egyptian Lotus and Lily; (vii) The AssyrianKnop-and-flower; (viii) Ivory from Nimrud; (ix) Achaemenid anthemion.637

-

7/28/2019 Asokan Pillars III

9/14

'ASOKAN' PILLARS: A RE-ASSESSMENT OF THE EVIDENCE - III: CAPITALS

s' %

CISSI~Yhr-AtACL.............. .........

G. The Eastern Mediterranean, Egypt, Western Asia and India.

here, from his own drawings,at Fig. H) he claimed these asthe keyto the problem.Althougha century ater than Aboka,these details of treatment, he maintained, must have beenworkedout at a much earlier (pre-Abokan)period in wood-carving. On top of this speculation he then constructed atheory which was weaker still. He asked us to believe thatthe petals,stamen and pericarpof the lotus-flowerasstylizedat Fig. H must have inspired the bell, rope-mouldingandabacus respectivelyof the Agokanpillar-capital.This argu-

H. Coomaraswamy's drawing of the Bharhut 'lotus-capital'.ment is too weak to convince anybody but the already con-verted; and knowingthat Coomaraswamybegan his careeras a botanistone is tempted to see it as the special pleadingof the erstwhile botanistriding his hobbyhorse!Our own differences with Coomaraswamy- and witheveryone else who has debated the origin of the 'Agokanbell' - begin with a refusalto acknowledgethe bell as a truelotiform. Can we really imagine artists of ancient Indiahaving depicted their most sacred of flowers with so littleregardor feeling for its true floral character? On the otherhand, if the Indian bell is not an inverted lotus-flower,asgenerallyassumed,what is it?Our own answer stems logically from acceptance of thehypothesisthat the prototypesof the first stone pillars hadtheir shaftsmade of wood, and their emblems of metal. This,we believe,was alsothe constitutionof the portablestandardsor dhvajasuch as the one shown at Fig. K, which we have

CopperDowel--- -Copper Dowel

S/-o,,sFoCord

Iri~i..... "i:i;: iiiBW:i~ii1'iiil,,;;,,

ShcFI~?

YItfI. The stone shaft of the Rimpiirvi lion pillar, showing the copper dowel.J. A copper dowel in a wooden shaft, with horizontal binding.

already recognised as being in the aesthetic lineage of themonumental 'Abokan'pillar.27In the case of the portablestandard, how would the metal emblem have been fittedto the top of the shaft or pole? The most obvious waywould have been by meansof a tenonor dowel,whichwouldhave necessitateddrilling a hole in the top of the shaft,justas we know the stonemasons did when they fixed stonecapitalsto stone stafts(see Fig. I). In stone, this would havepresented no technical problem. But in the case of wood,there would have been an obvious tendency for the shaftto split (especially if the standardwas a portable one andits emblem heavy in relation to shaft). To prevent this,a logical solution would have been to bind the outside ofthe shaftin the manner shown at Figs.J and K.28 However,

EMBLEMDOWEL r TANG oFcopper

UPPEREND oFBINDING,ABACUS- UPPsecurely Hedoround olePENDANTS oF hickcordorsHFened--BINDIN P corcio/h, covering indn B o cLOWEREND

oFBINDING ecurelybedlaroundpole,wi-hdctcoroaHvovennoy *-CLOTH STREAMER

POLE

K. Diagram showing the hypothetical construction of a portable dhvajaof thetype depicted at Bharhut.such horizontal binding would inevitably spoil the designby interruptingthe upward flow of the eye to the crowningemblem. To overcome this, it would have been necessaryto devise some means of coveringthe horizontalbinding, inorderto finish with a harmoniousverticaljunction satisfyingto the eye. Examinationof dhvajas epicted in earlyBuddhistrelief-sculptures an example of which was published withthe previous article at Fig. 3 and is repeated here as adrawing at Fig. K) suggests that normal practice was to27 THE BURLINGTON MAGAZINE, Vol. CXVI [1974], PP.712-13.28 It will be noticed that the stone shafts of AMokan'pillars are stepped backwith a circular ledge at the top. This enabled the shaft to be socketed into theunderside of the capital. This would have provided extra security for the heavystone capitals in an area bordering the Himalayan earthquake belt.

638

-

7/28/2019 Asokan Pillars III

10/14

'ASOKAN' PILLARS: A RE-ASSESSMENT OF THE EVIDENCE - III: CAPITALScover the binding with a device of cording or cloth. Thiswould have resulted in the cord or fabric hanging with aslight bulge, sufficient to explain the swelling contoursalready noted as a feature of the Indian bells in contrastwith Persepolitan (Fig. C). In this light, the 'AMokanbell'can be recognised as a fossilization in stone of a deviceoriginating in cord or fabric. In other words the Indianstonemason, true to his conservative reputation of clingingto forms evolved from earlier use of perishable materials,29was perpetuating as a purely visual convention the bell-likeform which had originated in other materials as the solutionto a practical problem.This in turn throws light on other features unique to the'Adokan' bell which have never been explained or evendiscussed before. One of them is the way in which the'Adokan' bell is designed to overhang the shaft.30 As onemight expect, this feature is particularly characteristic ofthe capitals we now know to belong to the Early or Pre-Adokan Group. In each case the sculptor has gone out ofhis way to emphasise this overhanging and even to makevisible part of the horizontal binding underneath - thelatter being conventionalised either as rope-moulding orbeading or both. This is most conspicuous in the case ofthe Sankisd elephant-capital which, when examined frombelow (Fig.8), shows not only the horizontal bindings (alsovisible under the bells of the other early pillars) but theunderside of the bell-pendents themselves ornamented witha conventional scroll-pattern.31 Such features are perfectlylogical in light of the hypothesis offered, but difficult toexplain in any other way.In medieval India, there seems to have been a partial

reversion to the deliberate depiction of the bell as a cordeddevice. At Fig.9, for instance, the sculptor has made noattempt to make the bell-pendents look like flower-petals.They are very obviously depicted as cording; and the motifswhich in the 'Adokan' bell look like the peeping tips ofsecondary petals are here given the obvious appearance ofhanging tassels.These conclusions about the origin of the Indian bell-form do not of course contradict the traditional claim ofWest Asian influence which we have already ackowledged.(The peeping-petal convention is a clear case in point.) Buttalk of West Asian influence in India should not confound

secondary influences with basic issues of form and style. Asfar as the latter are concerned, the 'Aiokan bell' is whollyand unmistakeably Indian.From bell, we now move to abacus, starting with an exam-ination of the so-called 'honeysuckle-motif'. The appearanceof this motif on the Indian pillars (Fig. E i to v) has long beenclaimed as evidence of Greek influence, supposedly broughtto India by 'Perso-Hellenistic craftsmen' employed byAdoka.32 However, no hard evidence has ever been adducedin support of this claim, which encourages us to re-examinethe issues afresh, uncommitted to any dogmatic attitude ofthe past.The first fact to note is that the term 'honeysuckle' wasapplied to Greek ornament, not by the Greeks themselves,but by Hellenic scholars who were natives of WesternEurope. When confronted with unfamiliar plant-motifs ofthe Ionic Order, they employed the names of plants ofnearest likeness with which they were familiar. Hence, theornament which the Greeks themselves called 'anthemion',from anthosa flower,33 was called in West European manualsof ornament 'honeysuckle', after the climbing plant sofamiliar in English midsummer hedgerows, properly knownas Lonicerapericlymenum. he reason for choosing this term isunderstandable, because the flower of the mature Greekanthemion (Fig. F v) is reminiscent of the curling petals ofLonicerapericlymenum;and the decorative scrollwork whichaccompanies the mature anthemion is not unlike the honey-suckle's twining stems and tendrils. Although the habitat ofgenus Lonicera extends to south-east Europe,34 the Greekspecies is different, with quite a different flower, in no wayresembling the anthemion of Greek art.Application of the English term 'honeysuckle' to the

29 A classic example of this conservatism is the Indian stonemason's imitaticnof mortice-and-tenon jointing when reproducing in stone the wooden railingsand gateways surrounding early sthpas. Such pointless imitation of techniquesabsurdly inappropriate in stone has sometimes been attributed to the inanitionand lack of inventiveness of the craftsmen concerned, but this is another ofthose entirely negative and superficial explanations which have done more todetract from the Westerner's understanding of Indian art than to guide him.The simple fact is that the sculptors of ancient India wanted their stonerailings and gateways to appear indistinguishable from wooden ones. Theonly reason they changed from wood to stone was lastingness. Otherwise theirreligious and ritual conservatism demanded that appearances should remainunchanged. It is fairly safe to conclude, moreover, that whether constructedin wood or stone, such features as railings and gateways were painted in thesame way, so that it would have been difficult to know at first sight the natureof the material underneath. The fact that lastingness was the sole reasonfor the change to stone is clear from the evidence of rock-cut temples: notonly were these designed in close imitation of wooden structures, but stone-masons went to the trouble of attaching wooden rafters to the ceilings of rockin order to counterfeit the appearance of a wooden building. Some fragmentsof these original rafters happen to have survived the last two thousand years,only because the cave served as shelter from the weather and was inhospitableto white ants.30 Comparing the bells at Persepolis, we note that the lower bells (Fig.7)which have been claimed as prototypes of the 'AMokan ell' are not designed togive the appearance of overhanging. On the other hand, the upper bells(Fig. L.) do share this characteristic with the Indian ones. We cannot excludethe possibility that the upper Persepolitan bell, like the 'Asokan', might havebeen influenced by some form of standard or votive pillar on which it fulfilleda function similar to that proposed for the Indian portable standard. This idea,first suggested to me by Miss Margaret Hall, is one that might be fruitfullyconsidered by students of Achaemenid architecture.31 I have not personally had the opportunity of examining the capitals of theEarly or Pre-Asokan Group of pillars at first hand. My conclusions are mainlybased on notes provided by Mrs Elinor Gadon who made a careful examinationfor me. They are reinforced by the photograph at Fig.8 kindly provided bymy colleague Dr Joanna Williams.

32 It is to the credit of James Fergusson that he did not fall into the trap ofassuming that the 'honeysuckle-motif' must have reached India through theagency of Greek art. He chose his words carefully (and, as we shall learn,correctly) when he wrote that the abacus of the Allahabad pillar represented'with considerable purity, the honeysuckle ornament of the Assyrians, whichthe Greeks had borrowed from them with the Ionic order'. J. FERGUSSON:IllustratedHandbook f Architecture, ol. I, London [1859], P-7. This makes allthe more surprising the fact that the theory of the Greeks having introducedthe honeysuckle-motif to India survives in some learned circles up to the presentday. See, for instance, s. D. DOGRA:Pella: Where Alexander the Great wasborn', Purdtattva,Bulletin of the Indian Archaeological Society, New Delhi,No. 7 [I974], pp.Io6-07.33 The etymology of 'anthemion' is discussed in further detail below, fn. 47.34 The logic of our argument remains unaffected by the fact that genus Lonicera(belonging to the botanical family Caprifoliaceae) extends over an even widerarea, from Mexico to Java. A species Lonicera itida is native to the Himalayanfoothills and Western China, but as in the case of the Greek species of Lonicerait has no relevance to the discussion, the flower having no resemblance to theanthemion.

639

-

7/28/2019 Asokan Pillars III

11/14

'ASOKAN' PILLARS: A RE-ASSESSMENT OF THE EVIDENCE - III: CAPITALSplant-ornament appearing on the Indian abacuses (Fig. E ito iii) is doubly misleading, because the Indian version ofthis motif is in fact neither honeysuckle nor Greek. Theevidence suggests that Greeks and Indians alike derivedtheir so-called 'honeysuckles' from the same source, whichwas West Asia - in particular, that extremely fertile regionof ornamental invention which stretched from Mesopotamiato Asia Minor. At a still earlier date, these same WestAsians had themselves been borrowers, because, as it isnow time to recognise, the ultimate source of the so-called'honeysuckle-motif' was the lotus as stylized in Egyptian art.It was earlier explained that the Egyptian and Indianspecies of lotus were entirely different. Yet, as religioussymbols they served precisely similar functions. They weresymbolic of the primordial waters from which emanated alllife in the universe, including the gods themselves.35 More-over, the two species were equally appropriate to thissymbolic role. The lotus-plant, by its very habit of growth,suggests productive union of sun and water. Rising from themuddy bottom of stagnant pools (suggestive of existencewithout life), and breaking the surface, it opens and closesits flowers at sunrise and sunset respectively, as if in ritualhomage to the sun, upon which the germination of thewaters depended. These associations are reinforced by thebotanical structure of the plant, which consists of a rootstockor rhizome which creeps along the bottom of the pool,producing nodes at intervals - each node bursting withfresh rootlets. Each rootlet in turn gives birth to more stemswhich then rise separately to the surface (see Fig. 17).36The lotus therefore served as a perfect image of the contin-uous perpetuation of life originating in the waters. To theancient Egyptians and Indians alike, it was the sacredflower par excellence.The drawing at Fig. F vi shows how, in Egyptian art,the lotus-flower was stylized in association with anothersymbol of fecundity - the so-called 'Egyptian lily' or 'Lilyof the South', the true botanical nature of which is notdefinitely known.37 These stylizations were often combinedin Egyptian art as alternating motifs, giving rise to a con-ventional type of continuous floral border which eventuallyspread in variously adapted forms throughout the civilizedworld. In a well-known Assyrian variation, the 'EgyptianLily' gave place to a bud, thus producing the 'knop-and-flower' motif (Fig. F vii). In another, the 'lily' was replacedby a palmette (Fig. F viii), which was simply a matter of

substituting one sacred life-symbol with another, the date-palm being pre-eminently the sacred tree of Mesopotamia.Both these variations took root in Asia Minor and becameprominent in the architectural ornament of the Ionians(Fig. F ii). It was from Asia Minor that the Greeks, duringtheir 'Orientalising Phase' in the sixth century B.C., derivedtheir own anthemion, already evident at Delphi in the sixthcentury B.C. (Fig. F iv), and reaching its mature form on theErechtheion at Athens in the fifth century B.C. (F v). By theGreeks the anthemion was used strictly as ornament for cymarectamouldings - usually as a frieze at the top of a pilaster.When Indians used the same West Asian motif, however, theyemployed it only as flat decoration on the rims of abacuses(Figs. E i to iii).

Beam of wikh EgypHanRoof 1o4us cop//'al OndIonic "asto-raCross-bear rn men aPr Cross-

Flu deeae//ColumnL. A capital from the Council Chamber, Persepolis (restored), showing thebell-like member.

At Fig. F v we see the anthemion in its classic and mosttypically Greek form, infused with strong feeling for orderand space, and for the symmetrical relationship of eachpart to the whole. As much care is given to the balance ofspaces between individual motifs as to the motifs themselves.The Indian treatment at Fig. E i to iii, on the other hand,is exactly the opposite. It reminds us of the claim that usedto be made by Western classical scholars that Indian artwas governed by horrorvacui. This is too superficial andnegative a charge to be taken seriously, but it does reflecta real and fundamental difference of attitude towardsornament. It might be said that the decoration of the abacusof the Sankisd elephant-capital (Fig. E i) is as typical of theIndian aesthetic as it is alien to the Greek; and by the sametoken, the Achaemenian rendering at Fig. F ix is as charac-teristically Iranian as it is alien to both the Greek and theIndian.One telling detail is the way in which the base or growth-point of the Indian'honeysuckle' at Fig. E i. is made to resem-ble a scaled mound or hillock. Nobody with eye and sensibilityattuned to Indian art would suppose that this resemblanceis accidental. Among other things, it reminds us of the'hill-and-crescent' motif appearing on early Indian punch-marked coins (Fig. M, left), which we also found on thecopper dowel securing the Rampurva lion-capital to shaft.38Obviously this was an important symbol in ancient India,but symbol of what? Nineteenth-century Indologists inter-

35 The role of the lotus as symbol of divine birth in both civilizations is too wellknown to need elaboration here. The Indian evidence is well summarised byj. AUBOYER:Le Trdne et son symbolisme dans l'Inde ancienne, Paris [1949], PP-74-Io4; and the Egyptian evidence by M. A. MORET: 'Le Lotus et la naissance desdieux en Egypte', Journal asiatique,Vol. 17 [1917], pp.499-513. The paralleltreatment of the lotus as a divine birth-symbol in Egyptian and Indian art isdiscussed by j. SCHUBERT: Der Gott auf der Blume, Ascona [r954].36 The botanical structure of the lotus and its use as a religious symbol wasbrilliantly expounded by F. D. K. BOSCH in The Golden Germ, published byMouton (Holland) [i96o]; but Bosch's treatment of the subject was marredby an historic approach which wrongly led him to interpret Indian lotus-symbolism as Rigvedic in origin. For a constructive criticism of Bosch's theories,see especially the review of the original Dutch edition by F. B. J. KUIPER: 'Naaraanleiding van de Gouden Kiem', Bijdragen ot de Taal-, Land-en Volkenkundevan Nederlandsch Indie, deel 107, 's-Gravenhave [1951], pp.67-85."7Conflicting opinions about the botanical origin of the 'Egyptian Lily' arediscussed by vivi TACKHOLM and MOHAMMED DRAR: 'Flora of Egypt', Part IV,Bulletin of the Faculty of Science, University of Cairo [1969], pp.148-56. 38 THE BURLINGTON MAGAZINE, Vol. CXV [November, 1973], p.713, Fig. B.640

-

7/28/2019 Asokan Pillars III

12/14

'ASOKAN' PILLARS : A RE-ASSESSMENT OF THE EVIDENCE - III : CAPITALSpreted it as a stfipa. Buihler seems to have been the first tosuggest that the 'staipa-symbol' may in fact be meant 'for arude representation of Mount Meru',39 the name given inlater Vedic literature to the 'mountains of the gods'. Thisidea was developed by A. K. Coomaraswamy, who drewattention to similar stylizations of sacred mountains inWestern Asia and the Mediterranean.40 However, it may bequestioned whether the term Meru is appropriate to a symbolwhich seems redolent of more archaic strata of myth. Inlight of some recent contributions to the study of earlyIndian cosmogony,41 we offer another hypothesis: the scaledhillock may be a symbol of the primordial hill of earliestIndo-Aryan tradition. This hill was believed to have risenfrom the bottom of the cosmic ocean in the first stage of

M. Symbols on early Indian punch-marked coins.

creation, and is variouslydenoted in the Vedas as girt,pdrvata-, nd ddri.The plausi-bility of this interpretationisreinforcedby the appearanceon other punchmarked coinsof a somewhatsimilar hillockwith a tree growing on top (Fig. M, right). This could very wellrepresent the world tree which, in the second stage of creation,grew out of the primordial hill fulfilling the dual function ofseparating and uniting heaven and earth. This tree ismetaphys-ically synonymous with the great prop or stay of the Vedicuniverse called skambha; 42 it is identified with the sacrificialstake oryfipa of the Vedic altar,43 and with the Indra-tree orIndra-dhvajaannually raised as a royal fertility rite and as are-enactment of Indra's original heroic deed of creating theworld.44The significance of the 'honeysuckle' as a symbol offecundity would have been greatly reinforced by its associa-tion with the primordial hill, which embodied the life-potential of the whole universe. But the superimposition ofimages does not stop there. The base or growth-point of the'honeysuckle' is also reminiscent of the form of a tortoise -another Indian symbol of creative power issuing from thewaters.45 Nor do we see as accidental the fact that the 'petals'of the Indian rendering of the 'honeysuckle' look like rearingserpents - the serpent or ndgabeing yet another key-symbol ofthe creative waters.'Ambivalence' is perhaps inadequate to describe thisevocative and peculiarly Indian habit of superimposingimages upon one basic form, so that the ultimate messagetranscends its individual components. Modern scientistshave coined a word which suits the case better: 'multi-valence'. This describes the power or capacity of certain

elements to combine with others and to produce a newwhole, transcending its parts. Here the 'honeysuckle', byassociation with the cosmic waters, the primordial hill, thetortoise and the serpent adds up to more than an image offecundity: it is nothing less than a symbol of the mysterysurrounding the whole of creation.If there is any lingering suspicion that the 'honeysuckleornament' might have anything to do with the plant of thatname, this should be finally dispelled by two features stillremaining to be noted. One is that the 'honeysuckle' asdepicted on the Indian abacuses sports its own flower inthe form of a rosette rising from a separate stem. Another,that the 'honeysuckle-flowers' are linked by horizontalcreepers indistinguishable from those of water-plants, andin particular the lotus rhizomata.This is not to say that Indian artists depicting the 'honey-suckle' were necessarily aware that the form had originatedwith a lotus. It is doubtful whether even the West Asianswho were intermediaries in the transfer of this motif fromEgypt to India were themselves aware that it was a lotus,since this was not a plant familiar to them at first hand.46Everything would suggest that both the West Asians andthe Indians saw the 'honeysuckle' primarily as a symbol offecundity.47 However, during the process of assimilation inIndia where the lotus was already endowed with the samesymbolic qualities, it was natural that the borrowed 'honey-suckle' should have been assimilated to the form of theIndian padma-lotus. Progressive stages of this transformationcan be recognised in the sequence of drawings at Fig. E i to v.On the Sanchi abacus it will be noted that the 'honeysuckle'already has Irhizomata indistinguishable from that of alotus.The lesson might be extended here to the Achaemenianhandling of the anthemion (Fig. F ix), which is somewhatstiff, and more strictly decorative in the sense that it seemsto lack any powerful overtone of 'sacred symbolism'. On thisground alone it is difficult to believe that the Iranian artistcould have inspired the anthemion in Indian art, so enormousis the aesthetic gulf between the two treatments.The final and perhaps the most clinching of all indicationsof the Indianness of the design on the Sankisd abacus(Fig. E i) is a tiny detail which seems to have escaped thenotice of those claiming Hellenistic influence. It is a leaf ofinverted heart-shape which recursin the spaces between the bud(or 'knop', as it is sometimes called) and rosette. The signifi-cance of this tiny detail in our context, and in light of every-thing that has gone before, is considerable, because nobodyalert to our subject could fail to recognise this as the leaf ofa pipul or asvattha tree - the cosmic tree of ancient India

9 Journalof RoyalAsiaticSociety 1907], p.529.40A. K. COOMARASWAMY:Notes on Indian coins and symbols', OstasiatischeZeitschrift,Vol. IV, Berlin [1927-28], pp.175-88.41 In particular, see F. B. J. KUIPER: 'The Bliss of Asa', Indo-Iranian ournal,Vol. VIII [1964], pp.96-129; and 'Cosmogony and Conception: a Query',Historyof Religions(University of Chicago), Vol. 10 [1970], esp. pp.98-129.42 Atharvaveda,X. 7 and 8. See also commentary by LOUISRENOU: tudesvediques tpanineennes,ome II, Paris [1956], pp.79-85.43 Rigveda,VIII. 8. Discussed by j. P. VOGEL:The Sacrificial posts of Isdpur',AnnualReport,Archaeologicalurvey f India, 1910o-I , pp.40-48.44 The best study of the Indra-dhvajas still j. j. MEYER'SrilogieAltindischerMdchteundFeste dervegetation,Part III, Zurich-Leipzig [1937].4 For the cosmogonic significance of the tortoise, see especially SdtapathaBrahmanaVII. 5.1.1. and 5.

46 Lotuses depicted in Assyrian art are directly derived from Egyptian repre-sentations, not from the plant itself, according to H'LPNE DANTHINE,p.cit.,p.47 (see fn. 23 above).47 The Greek term 'anthemion' applied to 'honeysuckle ornament' (fromanthos,a flower; anthiros,blooming; anthisis,the full bloom or flower of a plant)shares a common etymology with the term 'anther' which botanists apply tothe male organ in a flower. There is little doubt that the Greeks also saw theanthemion as a life-symbol, and one of its variant forms in Greek art depictsthe 'honeysuckle' sprouting out of a human bust (see HOWARD C. BUTLER:Sardis,American Society for the Excavation of Sardis, Leyden [1925], Vol. II, p.76).

641

-

7/28/2019 Asokan Pillars III

13/14

'ASOKAN' PILLARS : A RE-ASSESSMENT OF THE EVIDENCE - III : CAPITALSpar excellence.48 his tree was under worship in India from atleast as early as the third millennium B.C. as we can safelyinfer from seals found at Mohenjo-daro.49 Its symbolicpresence on the abacus of an 'AMokan'pillar is a powerfulreinforcement of the message we have already been readinginto the 'honeysuckle' frieze. This message will be stillfurther confirmed and elaborated as the total pictureemerges in the final article.Another motif recurring on the abacuses, no less importantthan the 'honeysuckle', is the hamsaor goose, always depictedin the gesture of pecking. 50 This is the bird which nineteenth-century Indologists invariably described as a swan, reluctantto accept that monuments as aristocratic and imperial as'Abokan pillars' could have been associated with anythingas prosaic to the Western mind as the common farmyardgoose. The confusion is significant because, without recog-nising this bird as the common wild goose anser Indicus,nobody could have been expected to understand the meaningof the pillars. As we shall eventually show, goose and lotusare twin keys to this understanding.On the mundane level, the links between goose and lotusare obvious. The goose is a waterbird, and the lotus is awaterplant. Furthermore, in Indian folklore the goose isconceived as feeding on lotuses. (This may explain, at leastin part, the gesture of pecking.) Even more pertinent, thegoose in India is associated with the promise of rain. Thisassociation arises in the first place from the bird's habit ofannual migration: it spends the dry season on the Indianplains; but before the onset of the monsoon it flies north-wards to its breeding-grounds in the Himalayas. Thus, everyIndian peasant is aware that when he sees a flight of geesebearing north, the longed-for monsoon clouds will not belong to follow.Since the goose is equally at home in the terrestial watersand in the upper celestial air (into which it wings its wayin a dramatic and beautiful flight, steep in trajectory), itwas perhaps inevitable that poets and mystics should haveseen it as an image of elevation to the divine spheres, andas a symbol of the union of heaven and earth.51 In the con-text of the pillars, we shall eventually see that the hamsa'sspecial role was that of linking the terrestial and celestialwaters - a role succinctly expressed in a hymn of the Rigveda(X.I24-.9) which describes the hamsa as 'companion ofthe never-resting waters'. The waters were conceived as'never resting' because of their continuous circula-tion between heaven and earth, in an unending rotarymovement, governed by the sun. With these hints about

the direction we shall be ultimately taking, we shall leavefurther discussion of the hamsauntil the final article.The 'honeysuckle', as earlier noted, is especially associatedwith the Early or Pre-Adokan Group of pillars. The hamsabridges both Groups, eventually appearing without the'honeysuckle'. But by the time we reach the Sdrndth pillar(postulated as the last erected by Asoka), both 'honeysuckle'and hamsa have entirely disappeared.52 Instead we have amuch larger abacus decorated with four circulating quadru-peds - bull, elephant, lion and horse - intercepted by fourwheels.In the first article we noted that the treatment of theanimals on the quadrupeds was lifelike in contrast with theheraldic lions on top, and that it suggested a mixed artisticpedigree - partly Indian and partly West Asiatic. This isnow the moment for closer study.Those who have claimed Hellenistic influence in thedesign of the Sirntth pillar have always focussed on thehorse (Fig.I3). As far as this animal's gait is concerned, weconcur. On the other hand, we would say of this horse, aswe said of the 'honeysuckle frieze' at Fig. E i, that the actualhandling of the borrowed subject-matter is as typical ofIndian art as it is alien to Greek. Far from expressing thevision of a Hellenistic artist guided by knowledge of anatomy,the Sarnath horse is rendered with total disregard for bonestructure.We suggest as a plausible speculation that the Indianwho carved the abacus of the Sirnith pillar was workingwith a foreign precedent in mind. He could very well havebeen copying from a design in metalwork, or from the typeof pattern-drawing commonly used by craftsmen workingin the repousse'echnique. The four animals circulating theabacus make us think of the quadrupeds circulating therims of gold or silver dishes in Achaemenid art.53 Thismay help to explain why the animals, although carved byan Indian hand and betraying the Indian aesthetic, do notseem to be observed from nature with the accuracy usualin Indian animal art.The eye of the elephant (Fig.14), for instance, is not thebeady little eye characteristic of that animal, which Indianartists usually rendered with great care and accuracy. It isindistinguishable from the eye of the bull it follows roundthe abacus (Fig.15). Similarly, it is a shock to the studentof Indian art to note that the bull is depicted with feethardly distinguishable from those of the lion at Fig.16. (Itis instructive to compare the feet of the bull on the abacuswith those of the bull crowning the Ramptirvi capital at

48The Bodhi tree at Bodh Gaya, under which the Buddha-to-be sought En-lightenment, was of the same species. For an excellent summary of the cosmicsignificance of the pipul or asvattha ree in ancient India, see ODETTEVIENNOT:Le culte de l'arbredans l'Indeancienne,Annales du Mus6e Guimet, Paris [x954],esp. Part I, chapter I.49SIRJOHNMARSHALL:Mohenjodarond the Induscivilization,Vol. III, London[1931], plate CXII, No. 387.50 As noted in the first article, the hamsa s also depicted, together with 'honey-suckle', on the altar-throne which was originally located under the Bodhi treeat Bodh Gaya beneath which the Buddha attained Enlightenment. THEBURLINGTONMAGAZINE,Vol. CXV [November, 1973], Fig. 20.51In the Upanishads, the hamsa's ole is conceived dialectically as both unitingandseparating. In its separating role the hamsarepresents the dtman's solationfrom Brahma as an equivalent of dehin,fva or ksetrajnathe latter especially inthe Sdmkhya-influenced Upanishads).

52 The hamsaand honeysuckle reappear in combination on the abacuses ofpost-Asokan brahmanical pillars, a classic example being the famous Heliodorsupillar at Besnagar, discussed in my article, 'The Heliodorus Pillar: a freshappraisal' - see fn. 13 above."3For an Achaemenian gold bowl with lions circulating the outside, see H. H.VONDEROSTEN: ie WeltderPerser,Stuttgart [1956], pl.72. This convention ofcirculating quadrupeds was well established in West Asian art long beforeGreek influence was felt. A particularly fine example is a bowl of carved rock-crystal now at Cincinnati (see HELENE. KANTOR:A rock crystal bowl in theCincinnati Art Museum', published as part of the Proceedings of the IVthInternational Congress of Iranian Art and Archaeology, 196o, in A SurveyofPersianArt, edited by ARTHUR PHAMOPE,Vol.XIV, Oxford University Press

- about 1962].).642

-

7/28/2019 Asokan Pillars III

14/14

'ASOKAN PILLARS : A RE-ASSESSMENT OF THE EVIDENCE - III.: CAPITALSFig.3). These points suggest that the Indian artist wasworking from a foreign pattern, not from observation ofnature.The next detail to note is that the wheel which interceptsthe animals on the abacus is not (as sometimes wronglysuggested) a symbolic Wheel of Law (dharma-cakra),ike thewheel which originally crowned the whole monument(Fig. N). It is unmistakeably the wheel of a chariot, realisti-cally depicted with the prescribed twenty-four spokes, andalmost identical with an excavated chariot-wheel of theperiod now preserved in Patna Museum (Fig.I8).From the moment the S rn~th pillar was discovered in1904, there has been much speculation about its meaning.These speculations have centred mainly upon the designof the abacus with its four quadrupeds intercepted by wheels,the hubs of the latter having originally been studded withprecious stones or metals.54 The first to speculate was VincentSmith, who claimed that the four animals represented theFour Quarters.55 Although most subsequent theorists tookSmith's ideas as granted and used them as the foundationof their own further speculations, it is important now tonote that the Four-Quarter theory has never been proved.Smith cited no evidence other than medieval sources, mostof them a thousand years or more later than the Sirn~thmonument. Except for Jean Przyluski56 and Paul Mus57who extended Smith's speculations with the help of verydubious parallels taken at second hand from writers onBabylonian astronomy (or more strictly, 'astrology')58nobody has contributed anything new to the subject.59

If the animals symbolise the Four Quarters, one wouldhave to explain why they are so obviously circulating themonument. In Indian thought, theFour Quarters are first and foremosta concept of fixity. Space was evenconceived in the image of an animal-skin stretched out and pegged at thefour cardinal points, hardly consis-tent with the idea of rotary move-ment conveyed by the design on theabacus.At this stage of our reassessment,we shall ignore speculation andrestrict ourselves to comment thatcan be confirmed by the evidence ofearlier literary sources. Within these,there is nothing to prove that bull,elephant, lion or horse were symbolsof the Four Quarters, or that theyfulfilled the roles of the Guardians ofthe Quarters in the later medievalsense. What we can say with cer-tainty, however, is that the fouranimals were especially associatedwith royalty. The chariot, too, wasassociated with royalty, and it wasalso pre-eminently an image ofcosmic movement.60 Thus the king,by driving a chariot parallel to thecourse of the sun at his consecration ceremony (rdjasuiya),was deemed to be aiding the rotary movement of the universeand thereby revivifying the forces of generation.61

Up to this point we are on sure ground. In the fourth andfinal article in this series, we shall try to fit together thedisparate strands of fact and weave them together into acoherent pattern, yielding from them at least an outlinepicture of what so-called 'Adokan' pillars are all about.

N. The Sirnmth pillar,restored.

"5DAYA AM SAHNI: Cataloguef theMuseumf Archaeology t Sarnath,Calcutta[I914], p.28.65VINCENTMITH:The monolithic pillars or columns of Asoka', ZeitschriftderDeutschenMorgenlandischenesellschaft, erlin, Vol. 65 [1911], pp.221-33.66JEANPRZYLUSaK:Le symbolisme du Pilier de Sarnath', Etudesd'Orientalisme(Mus6e Guimet, a la memoire de Raymonde Linossier), Paris [1932], pp.481-98.67 PAULMUS: Barabudur: esquisse d'une histoire du Bouddhisme fond6e surla critique arch6ologique des textes', Part IV, Bulletin de l'Ecolefranfaised'Extrgme-Orient,ol. XXXV, pp.413-28. Our critical attitude towards thisaspect of M. Mus's work does not detract from our high estimate of other parts,to which we are greatly indebted.Il Both Przyluski and Mus derived their ideas about Babylonian astronomyfrom the works of A.JEREMAIAS:Handbuch eraltorientalischeneisteskultur,erlin[1929], who in turn leaned heavily on Herodotus. The theory of planetarycolours andjewels is not to-day accepted by Assyriologistsworking from originalsources. For guidance on some of the issues raised by Przyluski and Mus I amgrateful to Mr David Pingree of Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island,whose studies on the relationship between Mesopotamian and Indian astronomyhave provided a new and valuable starting-point in this field (e.g. 'The Meso-potamian Origin of Early Indian Mathematical Astronomy', Journal or theHistoryof Astronomy,Cambridge, Vol. 4 [1973], pp.x-12).59Alfred Foucher, who saw the Sirnmth pillar as a specifically Buddhistmonument, naturally gave a strictly Buddhist interpretation. The elephant, hesaid, symbolised the Conception; the bull, the constellation under which the

Buddha-to-be was born; the horse, the 'Great Departure', and the lion, theBuddha himself as 'Lion of the Sakyas'. A. FOUCHER:9tudeurl'Artbouddhiqueel'Inde,Tokio [19291, P-33. From our point of view, these attributions merelybeg the question as to why these four animals were chosen in the first place. Weknow, in fact, that they belonged to a common stock of Indian symbols fromwhich Buddhism as well as all other religions drew, each using them in theirown way.60 In Indo-Aryan cosmology, the axle of a chariot, which both separates andunites the wheels of the vehicle, was an image of the axis mundiwhich similarlyseparates and unites heaven and earth (e.g. Rigveda,X. 89.4).61 These observations are abundantly confirmed by the role of the chariot inthe rites of the vdjapeyaceremony as well. See especially j. c. HEESTERMAN:Theancient ndianRoyalConsecrationescribedccordingotherajus textsandannotated,'S-Gravenhage [1957], esp. Chapter XVI. I am also indebted to Prof. Heester-man for opinion expressed in personal correspondence.

643