As4tcp paper

-

Upload

ruralfringe -

Category

Technology

-

view

348 -

download

0

description

Transcript of As4tcp paper

master, acting as a repository for an ever-increasing

set of demands, such as housing, retail

development, recreation, and waste management,

all the while constrained by the rigid application of

green belt policy. Accordingly, a patchwork spatial

structure has developed, driven by macro-scale,

rapidly implemented drivers of change such as

housing requirements, transport, retail and industrial

parks, and other large-scale infrastructure. Such

developments often generate significant land use

conflict and community protest, representing

contested visions of the kinds of urban-rural spaces

that are desired and needed.

Planning for the fringe has been characterised by

its urban-centricity, reactivity and piecemeal

approach, with little, if any, attention given to the

needs of the place itself – particularly from the

perspective(s) of those people who live, work and

engage with it on a daily basis. Essentially, the rural-

urban fringe is a passive and reactive space waiting

for something better to happen (as illustrated in the

cartoon overleaf). This runs counter to the spirit and

purpose of spatial planning, which seeks to marry

multi-scalar and multi-sectoral considerations within

a visionary and positive strategic framework in

which the potentiality of space is maximised.

Furthermore, viewing these spaces through a

The spaces where countryside meets town are

often among society’s most valued places, yet

these ‘fringe’ or ‘edge’ spaces are, arguably,

insufficiently well understood and usually lack any

kind of integrated management as places in their

own right. For many the fringe is synonymous with

the green belt; yet this only forms a constituent part

of this ‘messy’ space. Its ‘fuzzy’ boundaries are

elusive and dynamic, and uncertainty, diversity,

neglect, conflict and transition typify the rather

negative sentiment directed towards it. There is an

urgent need to think more imaginatively about how

we can manage environmental change in such

places more effectively.

Crucially, these rural-urban fringe spaces have

largely escaped planning and policy concern. Given

the speed, scale and focus of current changes to

the planning system, there is a risk that the

considerable potential for positive change in these

spaces will not be realised.

Squaring the need for better strategic

management with the emerging localism agenda

presents a significant planning conundrum. In most

cases the rural-urban fringe has no clear lines of

demarcation; it represents a ‘fuzzy’, ‘messy’,

‘transitory’ and dynamic edge to urban and rural

areas. Commonly it is subservient to an urban

the rural-urbanfringe – forgottenopportunityspace?Planning policy has consistently struggled to adapt to the multiple demands and rapidly changing nature of development within the rural-urban fringe; but Alister Scott and Claudia Carter argue that marrying the ecosystem approach with spatial planning provides a useful means of managing such spaces effectively

Town & Country Planning May 2011 231

different but complementary lens of the ecosystem

approach offers new interdisciplinary insights into

the wide range of ecosystem services provided by

the rural-urban fringe for society.

At its simplest, the ecosystem approach provides

a framework for the integrated management of land,

water and living resources. What, then, does nature

do for us in the rural-urban fringe? Ecosystem

services represent the academic and policy construct

where nature provides a diverse range of goods and

services from within the rural-urban fringe, ranging

from the air filtration function of trees, aesthetics

from the parkland landscape, and the flood

attenuation capacity of neglected scrubland.

Moving to an assessment of the environment in

relation to the goods and services that nature

provides for humans, the Millennium Ecosystem

Assessment1 groups ecosystem services under the

following headings:

● supporting services (necessary for the production

of other ecosystem services – for example soil

formation, photosynthesis, and nutrient cycling);

● provisioning services (ecosystem products – for

example food, fibre, and water);

● regulating services (including processes such as

climate stabilisation, erosion regulation, and

pollination); and

● cultural services (non-material benefits from

ecosystems – for example spiritual fulfilment,

cognitive development, and recreation).

However, whatever lens is used to view the rural-

urban fringe, policy has consistently struggled to

adapt to the rapidly changing nature of development

therein. Problems are further compounded by the

transitory nature of such places, with a single

fringe area often being shaped by multiple local

authorities, each with different local development

policies and working with limited cross-boundary

communication. The Regional Spatial Strategies

(RSSs) helped to cross such boundaries, but there

was widespread concern over their perceived top-

down imposition on local authorities, leading to their

‘Pickling’ under the new administration. Now

moving towards a localism imperative, many

authorities will simply be working with Unitary

Development Plans and Local Development Plans

with limited spatially-specific national policy or

strategic frameworks to guide them.

While the formation of Local Enterprise

Partnerships offers some potential, their role is

seemingly constrained by their business sectoral

remit; a lack of environmental representation

signifies a shift away from integrated perspectives.

However, one can chart some real opportunities –

as, for example, in the approved Greater

Birmingham and Solihull Local Enterprise

Partnership, which is enabling, for the first time,

rural and urban authorities and agencies to

collaborate in the name of sustainable economic

development. Here, the prevailing space of the rural-

urban fringe could represent key opportunity spaces

for new-style development activity.

Nevertheless, serious challenges to improved and

holistic management of such spaces remain. With

contesting land uses (for example between energy

and food production, commercial/ industrial

development, and greenspace preservation), it is

232 Town & Country Planning May 2011

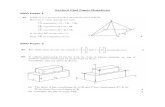

Used with kind permission, http://phil-sllvn.co.uk

Left

The rural-urban

fringe is seen as

‘a passive and

reactive space

waiting for

something better

to happen’

Town & Country Planning May 2011 233

becoming apparent that the rural-urban fringe

struggles to fit within the rigid, quasi-legal structure

of the current land use planning system. Indeed,

Qviström2 has usefully identified the fringe as

representing ‘landscapes of disorder’. In a challenge

to spatial planners, he argues that planners seek to

transform places into a specific order through

zoning and other planning functions. This

‘manicured’ spatial landscape therefore might

initially exclude different, innovative and creative

developments unless they are mainstreamed

through public support and protest (for example,

‘guerrilla gardening’ and permaculture fail to

conform to extant definitions of agriculture and

allotments).

Indeed, the current research3 on which this article

is based challenges the way we do planning and the

simple urban-centric view of its potential – hence

the characterisation throughout this article as ‘rural-

urban’ rather than ‘urban-rural’. For example, the

‘Incredible Edible’ initiative at Todmorden captures

this well, highlighting through ‘localism-style’

activity how local-scale food production can occur in

fringe locations.4 Such land uses do not fit within

our conventional land use classes, nor with current

planning rules. However, if we combine spatial

planning and ecosystem approaches to re-assess

the contribution and potential of such schemes, we

can adopt a new maxim of planning for what we

value rather than simply valuing what we plan.

This new way of seeing and deriving meaning and

potentiality from the rural-urban fringe can be used

as a framework in planning to connect the majority

of the human population, living in urban

environments, with their wider (natural)

environment. It also resonates strongly with spatial

planning theory, which moves away from the

regulatory fix of traditional land use systems to plan

spaces and places in a more integrated manner,

connecting planning issues across different scales

and different sectors to develop more proactive and

positive policies. However, these ideas have yet to

percolate through much planning practice, as many

planners remain either trapped or secure in ‘sectoral

bondage’.

If we rethink places and spaces in terms of the

multiplicity of services and uses that they are able

to provide, we might start to assess the rural-urban

fringe opportunity spaces in new ways, and so

maximise services and production through

innovative new planning policies and plans.

However, there are key challenges to be manage:

● Contested values and decision-making: As a

contested resource hosting multiple land uses,

the rural-urban fringe inevitably holds different

meanings for its various user groups. Power over

decision-making then becomes crucial in the use

to which such places are put. This raises issues of

inclusiveness, representativeness, transparency

and accountability, where the key challenge is

about reconciling the differing views and priorities

for the future of the rural-urban fringe and the

power relations involved. Planning tools such as

Strategic Environmental Assessment and

Environmental Impact Assessment value the

landscape in a policy context, but often at the

expense of socio-cultural and other hidden

economic values. Participation is still very much a

box-ticking exercise, with professional groups at

the forefront of decision-making.

● Community and environmental governance:Ecosystem services are anthropocentric and

emphasise human dependency upon the

environment. As a result, well designed

stakeholder consultation is required to establish a

collective and communitarian approach. This

philosophy fits well with the rural-urban fringe,

where multiple land uses and stakeholders can be

affected by management and development

proposals, and it has potential resonance within

the Government's localism agenda.

Assuming that the Localism Bill is enacted,

greater incentives for community consultation and

involvement in key planning decisions should have

a positive impact on the evolution of the rural-

urban fringe. In theory, the Localism Bill should

result in fringe areas being moulded more

explicitly to the needs of the local community,

allowing local groups to bid for public assets such

as recreational facilities and community groups to

take a more active role in land management.

However, there is a danger that localism will

empower well-off communities to actively

influence use and development (or no

development as the case may be), while hard-

pressed, deprived communities may struggle to

have an impact, potentially resulting in an rural-

urban fringe characterised by inequality and yet

more fragmentation.

‘In theory, the Localism Billshould result in fringe areasbeing moulded more explicitlyto the needs of the localcommunity... However, there isa danger that localism willempower well-off communities,while hard-pressed, deprivedcommunities may struggle tohave an impact’

● Long-term planning for the rural-urban fringe:The current spatial planning system rarely looks

beyond 20-year timeframes, and is seriously

affected by delays in plan-making so that evidence

used in support of a plan is long out of date

before the plan is implemented. As a society we

need to follow a more radical planning paradigm

that takes a long-term view and uses adaptive

planning and management processes. The rigidity

that characterises the current planning processes

should give way to flexible plans built on learning

gained through alternative pathways using the

ecosystem philosophy. This would enable a more

proactive stance which can more quickly respond

to unforeseen circumstances and pilot new ideas.

Such an approach would also allow us to plan

whole areas rather than a series of iterative

edges with no resilience and little in the way of

connectivity.

The rural-urban fringe is a unique space, with

values that are important to users from both urban

and rural areas. However, the current planning

system seems unable to manage these values in

an effective way. Incorporating ecosystem service

criteria into spatial planning frameworks seems a

useful way forward, offering many potential

benefits – and when better to do this than when

the current planning system is undergoing an

overhaul?

● Professor Alister Scott is Professor of Spatial Planning

and Governance, and Claudia Carter is Lecturer in

Environmental Management and Policy, in the School of

Property, Construction and Planning, Birmingham City

University. The views expressed here are personal.

Notes

1 Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: A Framework for

Assessment. Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA).

Island Press, Washington, DC, USA, 2003.

www.maweb.org/en/Framework.aspx

2 M. Qviström: ‘Landscapes out of order: studying the

inner urban fringe beyond the rural-urban divide’.

Geografiska Annaler, Series B, Human Geography,

2007, Vol. 89 (3), 269-82

3 ‘Managing Environmental Change at the Rural-Urban

Fringe’. Research Project, ESRC/Rural Economy and

Land Use Programme. ww.relu.ac.uk/research/projects/

and www.bcu.ac.uk/research/-centres-of-

excellence/centre-for-environment-and-

society/projects/relu. The research team combines both

academics and policy-makers/practitioners who

collectively contribute to the development, method,

implementation and learning in the 18-month project.

Their joint expertise has shaped this thoughtpiece:

Mark Reed, Nicki Schiessel, Ben Stonyer, Ruth Waters,

Peter Larkham, Karen Leach, Nick Morton, Rachel

Curzon, David Jarvis, Andrew Hearle, Mark Middleton,

Bob Forster, Keith Budden, David Collier, Chris Crean,

Miriam Kennet, and Richard Coles

4 See the Incredible Edible Todmorden website at

www.incredible-edible-todmorden.co.uk/

234 Town & Country Planning May 2011

![[XLS]eci.nic.ineci.nic.in/delim/paper1to7/TamilNadu.xls · Web viewRev. Dharmapuri & Kanniyakumari Paper 7 Paper 6 Paper 5 Paper 4 Paper 3 Paper 2 Paper 1 Index Tirunelveli (M.Corp.)](https://static.fdocuments.net/doc/165x107/5ad236e17f8b9a86158ce167/xlsecinicinecinicindelimpaper1to7-viewrev-dharmapuri-kanniyakumari-paper.jpg)