Arnold Schoenberg - Fundamentals of Music Composition (Ocr)

-

Upload

matias-vilaplana-stark -

Category

Documents

-

view

187 -

download

17

Transcript of Arnold Schoenberg - Fundamentals of Music Composition (Ocr)

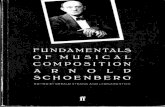

FUNDAMENTALS OF

MUSICAL

COMPOSITION

Also by Arnold Schocnberg

*STRUCTURAL FUNCTIONS Of' "AIlMOSY

STYLI! "SO 101l,l.

TllOOII;Y OF ""IUIONY

*edited by Erwin Stein

A"NOLD SCItOIlNllllItG: LIiTTI!RS

ARNOLD SCHOENBERG

FUNDAMENTALS OFMUSICAL

COMPOSITION

EDITED BY

GERALD STRANG

WITH THE COLLABORATION OF

LEONARD STEIN

11folxrandfolxrI.O!'~()ON· IOSTON

First published in 1967by Fabcr and Fabcr Limiled

) Queen Square London WCIN JAUFim published in this edition 1970

Printed in England by Oays Ltd, St IvC$ plcAll rights reserved

© Estate of Gertrude Schoenberg, 1967

Thu book. is sold subfrc//o the cOrldiliorl /hm i/ shall rIO/,

by way of Irad.! or Qtherwise, tw lem, rl'sold, hired ou/ar o/hl'rlVisl' circulaud lVi/haUl IM puhlisher's prior cQl1sem

In any form of binding or cove, a/hl'r thim Ilwl in ,,;hiehi/ is pu.hlisJred and ",ilhou.1 a similar condilion including this

cOrlditiorl beirlg imposed <)'1 the $IIbseqUf'rll purchaser

A CIP record for this book isavailable from the British Library

ISBN 0 571 01)276 4

14 16 18 20 19 17 IS I)

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

EDITOR'S PREFACE

EXPLANATORY NOTE

GLOSSARYPART I

CONSTRUCTION OF THEMES

I. THE CONCEPT OF FORM

1I. THE PHRASEComment on Examples 1-11Examples 1-11

Ill. THE MOTIVEWhat Constitutes a MotiveTreatment and Utilization of the MotiveComment on Examples 17-29Examples 12-29

IV. CONNECTING MOTIVE-FORMSBuilding PhrasesExamples 30--34

V. CONSTRUCTION OF SIMPLE THEMES (1)

I. BEGINNING Till! SENTENCe

The Period and the SentenceThe Beginning of the Sentence

lIIustrations from the literatureThe Dominant Form: The Complementary Repetition

Illustrations from the literatureComment on Examples 40-41Examples 35-41

xiii

X\li

34,8

999

11

16

16IS

20

20

20212121222223

CONTENTSCONTENTS

PDC~ 119

.19

""12012212J

12J\24126

VI. CONSTRUCTION OF SIMPLE TIIEMES (2)2. ANTECEDENT Of TItE PEIUOD

Anal)'$is of Periods from Bccthown'S Piano SonatasAnalysis of Other lUustrations from the LiteratureConstruction of the Antecedent

VII. CONSTRUCTION OF SIMPLE THEMES (3)

3. CONSEQUENT OF TItE PEIlIOD

Mclodie Considerations: Cadence ContourRhythmic Con1iderutiorl5Comment on Periods by Romantic ComposersExamples 42-:51

VIII. CONSTRUCTION OF SIMPLE TliEMES (4)4. COMPLnlON Of Tiff SENT£NC£

Comment on Examples S4-S6Illustrations from the literature

Examples S2-61

IX. THE ACCOMPANIMENTOmissibility of the AccompanimentT1Je Motive of the AccompanimentTypes of AocompanimentVoice LeadingTreatment of the Bass LineTreatment of the Motive of the AccompanimentRequirements of InstrumentsExamples 61-67

X. CHARACTER AND MOODExample 68

XI. MELODY AND THEMEVocal Melody

Illustrations from the literatureInstrumental MelodyMelody versus"_Examples 69-100

XII. ADVICE FOR SELF-CRITICISMlIlustratiollll of Self·Criticism

"..."""2621

29

29

29JOJO32

"",..,6J

82828J8J8466668788

9S........

10110.

10'

"'117

PART 11

SMALL FORMS

XIII. THE SMALL TERNARY FORMT1Je Small Ternary FonnThe Cootrastill& Middle Section

llIustratioos from the literatureComment 00 Examples 105-7The Upbeat ChordThe Recapitulation

Illustrations from the literatureExamples 101-7

XIV. UNEVEN, IRREGULAR AND ASYMMETRICAL CONSTRUCTION

Examples 108-12

XV. TI-IE MINUETn..F~

lIll1$lCations from the literatureThe: TrioExamples 113-19

XVI. THE SCHERZO1be A-SectionThe: Modulatory Contrasting Middle Section1bc: Practice Fonn

Illustrations from the literatureThe: RecapitulationExtensions, Episodes and Cod-euas

Further illustrations from the literaturen.. Co<bThe TrioExamples 120-3

XVII. THEME AND VARIATIONSSUuctural Constitution of the: 1bemeRelation between 11w:me and VariationsThe Motive of VariationProduction or the Motive or Variation

Illustrations rrom the literatureApplication aDd Elaboration or the Motive or Variation

Illustrations from the literatureCounterpoint in Variations

Illustrations rrom the literature

III119

14\

14\

142\4J.44

".\,\

'"\"l>J

'"'"1l>

'"'"'".61161\68

.69

.69

.69'111.111172\72

viii CONTENTS CONTENTS i,

Sketching the VariationsComment on Examples 126Organi:l:iltion of the SetExamples 124---7

PART III

LARGE FORMS

XVIII. THE PARTS OF LARGER FORMS (SUBSIDIARYFORMULATIONS)

The TransitionThe Transition with an Independent Theme

Illustrations from the literatureTransitions Evolving from the Previous Theme

Illustrations from the literatureThe Retransition

Illustrations from the literatureThe Group of Subordinate Themes

Illustrations from the literatureThe 'Lyric Theme'The Colla

Illustrations from the literature

XIX. THE RONDO FORMSThe Andante Forms (ABA and ABAB)Other Simple RondosVariations and Changes in the Recapitulation (Principal Theme)

Illustrations from the literatureChanges and Adaptations in the Recapitulation (Subordinate Group)

Illustrations from the literatureThe Large Rondo Forms (ABA-C-ABA)

Illustrations from the literatureThe Sonata-Rondo

Illustrations from the literature

XX. THE SONATA-ALLEGRO(fIRST MOVEMENT fORM)

The Sonata-AllegroThe ExpositionThe Principal Theme (or Group)

Illustrations from the literatureThe TransitionThe Subordinate Group

illustrations from the literatureThe Elaboration (Durch/Uhrung)

Illustrations from the literature

pag~ 173l73

17'

'"

178

17811911918018018118118318318418'186

190190192193193194194

19'196197197

199

200201202202203204204206207

The RetransitionThe Recapitulation

Illustrations from the literatureThe Coda

Illustrations from the literatureConclusion

APPENDIXFundamentals of Musical Composition (Author's Statement)

INDEX

pag~ 2092092102122122ll

214214

216

INTRODUCTION

THIS present book rcprc~nts the last of the three large textbooks on music theoryand practice planned by Arnald Schoenberg lar~ly as the result of his teachings inthe United States. Like the two other books, Structurtll FUllctions of Harmony(Williams & Norgate, 1954) and Preliminary Exercises in Counterpoint (Faber &.Faber, 1963), Ihis one was intended for "the average student of the universities' 35 wellas for the talented student who might become a composer (see Schocnbcrg's statementin the Appendix). As the author states, it was planned as a book of 'technic:l.1matters discussed in a very fundamental way',

Fundamentals 0/ Musical Composition combines two methods of approach: (I) theanalysis ofmasterworks, with special emphasis on the Beelho~n piano sonatas; and(2) practice in the writing of musical forms, both small and large. As a book ofanalysis it amplifies much in the laler chapters of Structural Functions oj Harmony.particularly Chapter XI, 'Progressions for Various Composilional Purposes', As amethod for preliminary I'xercisf'S in composition itenlarges the mat~rialof the syllabus.Mode/sjor &ginners in Composition (G. Schirm~r. Inc.• 1942).

In Fundamenlals of Musical Composition, as in all of his manuals of musicalpractice dating back to his Harmonif'lehre{Unh-ersal Edilion, 1911; abridged Englishtranslation, Theory of Harmony, Philosophical Library, 1948), Schoenberg's main~dagogical approach is not just one of theoretical speculation-although onc willalways find a basic theor~tical foundation underlying his practical advice-but ofexposing fundamentallechnical problems in composition and of showing how theymight be solved in a number of ways. Through such an approach the student isencouraged to develop his own critical judgement based on the evaluation of manypossibilities.

LEONARD STEIN, 1965

EDITOR'S PREFACE

TilE Fundamentals of Musical Composition grew out of Schoenbcrg's work with sludents of analysis and composition at the University of Southern California and theUniversity of California (Los Angeles). Work on it continued intermittently from1937 until 1948. At the lime of his death most nfthe text had undergone fOUT more orless complete revisions. During these years hundreds of special examples were writtento illustrate the text. In the final version a great many of them were replaced byanalyses of illustrations from musical literature, and many others were transferred10 Structural Functions of Harmony.l

Since I had worked with Schoenberg on the book throughout the entire period.Mrs. Schoenberg asked me to assume the task of reconciling the various versions andpreparing it for publication. The text was substantially complete up to and includingthe chapter on 'Rondo Forms'; only revision of the English and elimination ofsome duplications were necessary. The final chapter was incomplete and required reorganization because much of its content had been anticipated in the earlier chapteron 'The Parts of Luger Forms',

From the very beginning the book was conceived in English, rather than in Schoenberg's native German. This created many problems of terminology and languagestructure. He rejected much of the tradilional terminology in both languages, choosing, instead, to borrow or invent new terms. For example, a whole hierarchy of termswas developed lo differenliate the subdivisions of a piece. Part is used non-restrictivelyas a general term. Other terms, in approximate order of size or complexity, include:motil'e, unit, element, phrase, fore-sentence, after-sentence, segment, section anddivision. These terms are used consistently and their meanings are self-evident. Otherspecial terms are explained in the text. I have chosen to keep some of the flavour ofSchoenberg's English construction, when it is expressively effective, even thoughit may be at variance with the idiomatic.

The aim of this book is to provide a basic text for undergraduate work in composition. Thus the first half is devoted to detailed treatment of the technical problemswhich face the beginner.1t is intended to be thoroughly practical, though each recommendation and each process described has been carefully verified by analysis of thepractice of master composers. From this poinl on, the basic concepts, structures and

, Arnold Schexnbcrl, $I,,,el"rol F"nel;ofUo!Ha,molly. New York: WiHiall1$& NOrf!:3Ie, L:mdon, 1954.

EDITOR'S PREFACE

techniques are integrated by applying them to the traditional instrumental forms, inapproximate order of complexity.

Schoenberg was convinced that the student of composition must master thoroughlythe traditional techniques and organizational methods, and possess a wide and intimate knowledge of musical literature if he wishes to solve the more difficult problemsof contemporary music. In this basic text there is little reference to music since 1900,though the student is encouraged to make full use of the resources available up tothat time. Nevertheless, the principles stated here can be readily applied to a varietyof styles and to contemporary musical materials. Certain aesthetic essentials, such asclarity of statement, contrast, repetition, balance, variation. elaboration, proportion.connexion, transition-these and many others are applicable regardless of style oridiom.

While primarily a textbook on composition, it will be evident that this volume canbe used equally well as a text in musical analysis. As such, it emphasizes the composer'sinsight into musical organization; it is not a mere vocabulary of formal types. Thcexamples are deliberately chosen to illustrate a wide variety of departures from thefictitious 'norm'. Only acquaintance with a wide range of possibilities gives the studentenough freedom to meet the unique problems which each individual compositionposes.

To simplify the student's analytical problems and rcduce the number of lengthymusical examples, most of the rcferences to musical literature are confined to theBeethoven piano sonatas. The first volume of the sonatas, at least, must be considereda required supplement. In latcr chapters references are broadened to include worksof other composers which are readily available in miniature scores!

It was a privilege and a deeply rewarding educational experience to have workedwith Schoenberg over these many years on the preparation of this book. I have tried,in preparing this final version, to secure the clear and faithful presentation of the ideaswhich grcw and matured during his experience with American composition students,ideas which were verified by a broad and intensive study of musical literature. All hislife Schoenberg laboured to share with his students his knowledge of music. I hopethat through this. his last theoretical work on composition. another generation ofstudents may share his inspiration.

GERALD STRANG. 1965

EXPLANATORY NOTE

ALL citations of musical literature which do not specify the composer refer to works byBeethoven. If the title is not specified the reference is fO his piano sonatas. Opus number andmovement are specified thus: Op. 2/2-111 means B«thoven, Piano Sonata, Opus 2, No. 2,third movement.

Measure numbers arc specified from the first accented beat of the passage. even though apreceding upbeat is a part of the phrase.

In numbering measures the firstJuJ/ measure is numbered one. Where there are alternativeendings thc second ending starts with the same measure number as the first ending, with anadded subscript, e.g. Op. 2/2-1, in which the first ending contains m. 114-17. The Sfi:ondending accordingly begins with m. 114a. 1150, 1160 and 117a. M.118-21 complete thesecond ending. Thedouble bar lies within m. 121 ; hence, the first full measure after the doublebaris m. 122.

Keys or tonalities arc represented by capital or small letters to indicate major or minor:a means a minor key on A; F# means a major kcy on f,,#. Keys reached by modulation arcoften paired with the Roman numeral indicating the relation of the tonic chord to that of theprincipal key: from C, modulation might lead to G(V), e(iii), A~ (~VI)J(iv), etc.

The Roman numerals representing chords also reflect chord quality; I is major; vi isminor, etc. Substitute, or chromatic, harmonies, are often distinguished from the diatonicequivalent by a bar tbrough the middle: h'i means a major chord on the third degree substituted for the diatonic minor chord. This same chord in a different context might be referred to as V of vi, i.e. the dominant normally resolving to vi, as in the key of tbe relativeminor.

The distinction between a transient modulation and chromatic harmony is alwaystenuous. In general, only finnly established modulations lead to analysis in terms of adifferent key. However, when a chromatic passage remains temporarily among chordsassociated with another key, the term region is used. Thus a reference to the tonic minorregion, or subdominant minor region, indicates temporary use of chords derived from thecorresponding key, but without fully establishing the new key by a cadencc.1

The following abbreviations are used throughout the book:

Var(s). = variation(s)Ex(s). = ellample(s)

• For further explanation of rqloll and modM/Qlum, _ S<:hocllbel'&. $lruclllTo/ FIl/I,rUms of HQrmtHly.Qlapter Ill.

GLOSSARY

OrigiNJI wage

whole notehalf notequancr note:ei&hth Dote

'on<tonalitydegree (u V or vii)measure (m.)voic&-leading (or part-leading)authentic cadencedeceptive cadence (or progression)

Equimknl U1glish usage

semibreveminimcrotchetq~~

no"koychord built on a degree or the scalebupart.writingperfect cadeoocinterrupted cadence

PART I

CONSTRUCTION OF THEMES

I

THE CONCEPT OF FORM

TH Eterm/orm is used in sc~ral different senses. When used in c:ooncxion with binary,Il',nary or ,andoform. it refers chiefly 10 the number of parts, I The phrase sonola/armsuggests, instead, the size of the parts and the complexity of their interrelationships.In speaking of minuet, scher:o and olher doJrce forms. one has in mind the metre,tempo and rhythmic characteristics which identify the dance.

Used in the aesthetic sense, form means that a pica: is organizt!d: i.e. that it consistsof elements functioning like those of a living organism.

Without organi7.3lion music would be an amorphous mass, as unintelligible as anessay without punctuation, or as disconnected as a conversation which leaps purposelessly from onc subject to another.

The chief requirements for the creation of a comprehensible form are logic and(·ohcrellu. The presentation, development and interconnexion of ideas must be basedon relationship. Idcas must be dilfcrentialed according 10 Iheir importance andfunction.

Moreover, one can com~rchend only what onc can kttp in mind. Man's mentallimitations prevent him from grasping anything which is too extended. Thus appropriate subdivision facilitates understanding and determines the form.

The size and number of parts does not always depend on the size of a piece.Gcnerally, the larger the piece, the greater the number of parts. But sometimes a shortpiece may have the same number of parts as a longer one, just as a midget has the!>:tmc number of limbs, the same form, as a giant.

A composer does not. of course, add bit by bit, as a child does in building withwooden blocks. He conceives an entire composition as a spontaneous vision. Then he

, 'Parl' i. ll.'lCd in lhe m(>$t general ",nse 10 indicale undifferentiated elcmcnlJ, !ICClions or .ubdivi.ion,"f a pieo:. Other temtS will be used laler 10 dislingui.h parts of variOl8 sizes and with different runctio~.

2 CONSTRUCTION OF THEMES

proceeds, like Michclangclo who chiselled his Moses out of the marble withoutskelchc.-s, complttc in every detail, thus directly jorming his material.

No beginner is capable of envisaging a composition in ilS entirety; hence he mustproceed gradually, from the simpler to the more complex. Simplified practice forms,which do not always correspond 10 art forms, help a student 10 acquire Ihe sense ofform and a knowledge of the essentials of construction. It will be useful 10 SlaTt bybuilding musical blocks and connecting them intelligently.

These musical blocks (phrases, mOlhes, elc.) will provide the material for buildinglarger units of various kinds, according to the requirements of the structure. Thus thedemands of logic, coherence and comprehensibility can be fulfilled, in relation to theneed for contrast, variety and fluency of presentation.

1I

THE PHRASE

THE smallest structural unit is the phrase, a kind of musical molecule consisting of anumber of integrated musical events, possessing a certain completeness, and welladapted to combination with other similar units.

The term phrase means, structurally, a unit approximating to what one could singin a single breath (Ex. 1).1 Its ending suggests a form of punctuation such as a comma.Oflen some features appear more than once within the phrase. Such 'motivic'characteristics will be discussed in the following chapler.

In homophonic-harmonic music. the essential content is concentrated in one voice,the principal voice. which implies an inherent harmony. The mutual accommodationof melody and harmony is diffICUlt at first. But the composer should never invent amelody without being conscious of its harmony.

When the melodic idea consists entirely or largely of notes outlining a single harmony. or a simple succession of harmonies. then: is little difficuhy in determining andexpressing the harmonic implications. With such a dear harmonic skeleton. evenrather elaborate melodic ideas can be readily related to their inherent harmony.Exs. 2 and 3 illustrate such cases at several levels. Almost any simple harmonic progression can be used, but for opening phrases I and V arc especially useful, since Iheyexpress the key most dearly.

The addition of non-chordal notes contributes to the fluency and interest of thephrase, provided they do not obscure or contradict the harmony. The various 'conventional formulas' for using non-chordal notes (passing nOles, auxiliary notes.changing notes. suspensions, appoggiaturas, etc.) provide for harmonic claritythrough the resolution of non-chordal into chordal notes.

Rhythm is particularly important in moulding the phrase. It contributes to interestand variety; it establishes character; and it is often the determining factor in establishing the unity of the phrase. The end of the phrase is usually differentiated rhythmicallyto (H"ovide punctuation.

Phrase endings may be marked by a combination of distinguishing features. suchas rhythmic reduction, melodic relaxation through a drop in pitch. the use of smallerinterval' and fewer notes; or by any other suitable differentiation.

The length of a phrase may vary within wide limits (Ex. 4). Metre and tempo have11 great deal to do with phrase-length. In compound metres a length of two measures

I Exs.I-11 at end Qr<;haptcr, pp. S-7•

•

• CONSTRUCTION OF THEMESTHE PHRASE ,

may be considered the average; in simple metres a length orrouc measures is normal.But in very slow tempos the phrase may be reduced 10 half a measure; and in veryrapid tempos eight measures or more may constitute a single phrase.

The phrase is seldom an exact multiple of the measure length; it usually varies bya beat or more. And nearly always the phrase crosses the melrical subdivisions, ratherthan filling the measures completely.

There is no intrinsic reason for a phrase 10 be restricted to an even number. But theconsequences of irregularity are 50 far reaching that discussion of such cases will bereserved for Chapter XIV.

COMMENT ON EXAMPLES1

(0 the early stages a composer's invention seldom Rows freely. The control ofmelodic, rhythmic and harmonic factors impedes the spontaneous cooc:eplion ormusical ideas. It is possible to stimulate the inventive raculties and acquire technicalracility by making a great many sketches or phrases based on a predetermined harmony. At first, such attempts may be stiff and awkward, but, with patience, theco-ordination or the various elements will rapidly become smoother, until realfluency and even upressi~ness is attained.

En. 5-11 may be taken as an outline ror practise. Here a single harmony, the tonicor Frnajor, is taken as a basis. Ell:. 5shows a rew or the contours which can be createdby various arrangements or the notes or the chord. In Ex. 6 smaller note-values produce different U5UItS. Ell. 7, still confined to notes or the chord, illustrates the varietythat can be achieved by combining different note-values (study also us. 2tI,~, h).

Exs. 8 and 9, based on En. 5 and 7, show how the simplest melodic and rhythmicadditions can contribute fluency and vitality (study also Exs. 2 and 3).

The more elaborate embellishments or Exs. 10 and 1I contribute flexibility andrichness or detail, but tend to overburden the melody with small notes and obscurethe harmony.

• The U:llnplcs will come:1I the ends or chapters rollowinl the 'Convncnt on Eumplcs'.

El.3

l~:::l~:: C ~I:f:::c

.............~.!""'--------------------------------------_.

1

• CONSTRUCTION OF T1iEMES THE PHRASE 7

EI.9Varying Ell'.7 by adding pasling notes and nole repetitions

.rru _

I

n

EI.5Ndodic anit. deri"ed from broken chords

.1 W cl ~§!~~i'~l~~

£ll'.6Smaller note v.tun

.) .) e) oIJ 0) f'l .J

~rrJrlrrrr~JrJ~

n •

Er."Varying ES,7 by usitIK .pp~.taras &.Dd changillg notes

~ .)

IJ)trrr~

• •~rvl~

.. ......

THE MOTIVE 9

III

THE MOTIVE

EVEN the writing of simple phrases involves the invention and use of motives,thoughperhaps unconsciously. Consciously used, the motive should produOl: unity, relationship, coherence, logic, comprehensibility and fluency.

The motive generally appears in a characteristic and impressive manner at thebeginning ofa piece. The features of a motive are intervals and rhythms, combined toproduce a memorable shape or contour which usually implies an inherent harmony.Inasmuch as almost every figure within a piece reveals some relationship to it, thebasic motive is often considered the 'germ' of the idea. Since it includes elements, atleast of every subsequent musical figure, onc could con5ider it the 'smallest commonmultiple'. And since: it is included in e~ry subsequent figure, it could be consideredthe 'greatest common factor'.

However, everything depends on its use. Wheth~r a motive be simple or complex,wh~th~r it consists of few or many features, th~ final impression of the pieee is notd~termined by its primary fonn. Ev~rything depends on its treatm~nt and developm~nt.

A motive appears constantly throughout a piece: it is r~pt'Dted. R~pctition aloneoft~n gives rise tomonotollY. Monotony can only be ov~rcom~ by mriotjon.

Use of the molil'e requires l'Or;o';on

Variation means change. But changing every feature produces something foreign,incoherent, illogical. It destroys the basic shape of the motive.

Accordingly, variation requires changing some of the I~ss-important features andpreserving some of the mor~-important ones. Preservation of rhythmic f~atur~s

effectively produces coherence (though monotony cannot be avoided without slightchanges). For the rest, det~rmining which features are more important depends on thecompositional obje<:tive. Through substantial changes, a variety of mOfil'e-!orms,adapted to every formal function, can be produced.

Homophonic music can be called the style of'developingvariation'. This means thatin the succession of motive-forms produced through variation of the basic motive,there is somcthing which can be compared to development, to growth. But changesof subordinate meaning, which have no special consequences, have only the IOC<'l1effect of an embellishment. Such changes are better termed mrjonls.

WHAT CONSTITUTES A MOTIVE

Any rhythmicized succession of notes can be used as a basic motive, but there shouldnot be too many different features.

Rhythmic features may be very simple, even for the main theme of a sonata (Ex.120). A symphony can be built on scarcely more complex rhythmic features (Exs. 12b,c, 13). The examples from Beethoven's Fifth symphony consist primarily of note~

repetitions. which sometimes contribute distinctive characteristics.A motive need not contain a great many interval features. The main theme of

Brahms's Fourth symphony (Ex. 13), though also containing sixths and octaves, is,as the analysis shows, constructed on a suttesSion of thirds.

Often a contour or shape is significant, although the rhythmic treatment and inler~

vals change. The upward leap in Ex. 120; the movement up by step in Ex. 16; theupward sweep followed by a return wilhin it which pervades Beethoven's Op. 2/J-IV,'illustrate such cases.

Every element or feature of a mOlive or phrase must be considered to be a motiveif it is treated as such, i.e. if it is r~pcated with or without variation.

TREATMENT Aro;o UTILIZATION Of TIlE MOTIVE

A motive is used by repetition. The repetition may be exact, modified or developed.Exact repet;t;onsprcserve all features and relationships. Transpositions to a different

degree, inversions, retrogr3des, diminutions and augm~ntationsare exact repetitionsif th~y preserve strictly the features and note relations (Ex. 14).

ModiJi~d r~pelilionsare created through variation. They provide variety and produceoew material (motive-forms) for subsequent use.

Some variations, however, are merely local 'variants' and have lillle or no influ~nce

on the continuation.Variation, it must be remembered, is repetition in which some fealures are chan~d

and the rest preserved.All the features of rhythm, interval, harmony and contour arc subject to various

alterations. Frequently, several methods of variation are applied to several featuressimultaneously; but such changes must not produce a motive-form loo foreign to thebasic motive. In the course ofa piece, a motive-form may bedeveloped furtherthroughsubsequent variation. Exs. 15 and 16 arc illustrations.

COMMENT ON EXAMPLES

In Exs. 17-29, based solely on a brokcn chord, some of the methods which can beapplied arc shown as systematically as is practicable.

1 Refen:n.ces to the literature idenlirocd only by opu~ number apply 10 Ilcctho""n piano ~onatas. lkcauscof Iheir general accessibility. n ereal m"oy refereo<:o 10 Ihern appear in the latcr chapters.

•, ...;;a, _

10 CONSTRUCTION OF THEMES

The rhythm is changed:

I. By modifying the length of the notes (Ex. 17).2. By note repetitions (£Xs. 1711, i, k, I, n).3. By repetition of certain rhythms (Exs. 17/, m. 1&).4. By shining rhythms to different beats (Ex. 23; in particular. compare 23J with

2k,f. g).5. By addition of upbeats (Ex. 22).6. By changing the metre-a device seldom usable within a piece (Ex. 24).

The i1/(errols are changed:

1. By changing the original order or direction of the notes (Ex. 19).2. By addition or omission of intervals (Ex. 21).3. By filling up intervals with ancillaryl notes (Exs. 18,20 fT.).4. By reduction through omission or condensation (Ex. 21).5. By repetition of features (Exs. 20h, 22a, b. d).6. By shifting features to other beals (Ex. 23).

El.13

=:~··~:·t=:r I :e:r::J1The harmony is changed:

1. By the use of inversions (Exs. 25a, b).2. By additions at the end (Exs. 25 c-i).3. By insertions in the middle (Ell.. 26).4. By substituting a different chord (Exs. 27a, b. c) or succession (Exs. 27d-i).

The me/od}' is adapted to these changes:

I. By transposition (Ex. 28).2. By addition of passing harmonies (Ex. 29).3. By 'semi-contrapuntal' treatment of the accompaniment (Ex. 29).

Such exploration of the resources of variation can be of great assistance in theacquisition of technical skill and the development of a rich inventive faculty.

• In onkr 10 avoid _hdically miskadina and f;()flUpted tetms, _illar, will be preknat in rd"errina10 the S(toCllled ·embdlish;...• 0<" 'ornamental' notes of c:onvcnlion:ol melodic formulas.

~,~.2- ...L ...L ...L

••~ .. J... ".

~-• .1 .' ..

..

CONSTRUCTION OF THEMES

Et.21Rdllction, omission, condtnution

~r'r' ~J

THE MOTIVE "

EK.22Addition of upbeats, repetition of rn.turu~I" _blC>~"rQj_ _

~rr_~r~r r j:J

~r~'.~tr err~

~~r E!fJ:ill±ir IDJ~E:..18Addition of ancill&r}' Dotu

• ..~'~~rw·r,"J~!:.o _

CONSTRUCTION OF THEMES THE MOTIVE

Ex.29.)

"

~~~.~••~~~~4.~... _

CONNECTING MOTIVE-FORMS 17

IV

CONNECTING MOTIVE-FORMS

ARTISTICALLY. the connexion of motive-fonns depends on factors which can onlybe discussed at a later stage. However, the mechanics of combination can be describedand demonstrated, while temporarily disregarding the stiffness of some of theresulting phrases.

Common content, rhythmic similarities and coherent harmony contribute to logic.Common content is provided by using motive-forms derived from lhe same basicmotive. Rhythmic similarities act 3S unifying elements. Coherent harmony' reinforcesrelationship.

In a general way every piece of musK: resembles a cadence, of which each phrase willbe a more or less elaborate part. In simple cases a mere interchange of I-V-I. if notcontradicted by controversial harmonies,can express a tonality. As used in traditionalmusic. such an interchange is generally concluded with a more elaborate cadence_-

Ordinarily the harmony moves more slowly than the melody; in other words, anumber of melodic notes usually refers to a single harmony (En. 43,44, 45, 58, ete.).SThe contrary occasionally occurs when the harmony moves quasi-oontrapuntallyagainst a melody in long notes ('Eu. 51c, m. 17. 58g). Naturnlly, the accompanyingharmony should reveal a certain regularity. As motive of the harmony and molil't!! ofthe Qccomp(lIIiment. through motive-like repetitions. this regularity contributes tounity and comprehensibility (Chapter IX).

A well-balanced mclody progresses in waves. i.e, each elevation is countered bya depression. It approaches a high point or climax through a series of intermediatelesser high points, interrupted by recessions. Upward movements are balanced bydownward movements; large intervals 3rc compcnS3ted for by conjunct movement inthe opposite direction. A good melody generally remains within a reasonable compass, nol straying too far from a central range.

BUILDING PIIRASES

Exs. 30--34 show various methods of producing a large number of different phrasesout of one basic motive. Some of them might be used to begin a theme, olhers 10

I The: cOoc<:pt of coherenl humon)' ~d here i. deduced from lhe: practice of the period From 8;J.ch 10Wasncr•

• For evalualion and e~planalionof the 'rool progn:lolions', lIOC Amold Schoeobc:rs, 17,rory 01 ffam_y,pp. 70 If.. and StruCluru{l'utrefl'olU 01 HamtOny, Chapltr 11.

I Eu. 4Z-S I al eno of Chapltr VII; E.u. SZ~1 at cnd of Chapler VIII.

continue it; and some, especially those which do not begi.n wit~ I, as matcria~ tomeet other structural requirements, e.g. contrasts, subordinate Ideas and the Itke.Motivic features are indicated by brackcls and IcUers. A detailed analysis will revealIllany additional relationships to lhe basic motive.

In Ex. 3\ the original form is varied by adding ancillary notes. though ~II notcs ofthc basic motive arc retained. In Ex. 32 the rhythm is preserved, prodUCing closelyrelated motive-forms in spite of changes in interval and direction. Combined withtranspositions to othcr degrees, this procedure is often used in traditional music toproduce entire themes (sce. for cxample, Ex. 52). In such cases each note of the melodyIS either a harmony note or a non-chordal note that corresponds to onc of the cstablished conventional formulas.

In Ex. 33 more far-reaching variations are produced by combining rhythmic.cha~ges

with the addition of ancillary notes., as well as with changes of interval and dl~,on.

Even though some of the examples arc rathcr stiff and overa:o~dcd, the praclu% ofmaking such sketches. which attempt various methods of vanatton. should never be

abandoned,Other far-reaching variations are shown in Ex. 34. Through such rhythmic shifting

and rearrangement of features, material is produced for the continuation of extendedthcmes. and for contrasts, But the use of such remotely related motive-forms may

endanger comprehensibility.In working out derivatives of a motive, it is important that the results have the

character of true phrnses-<tf complete musicalllnits.

CONSTRUCTION OF THEMES CONNECTING MOTIVE-FORMS

"

------ ri<

CONSTRUCTION OF SIMPLE THEMES (I) 2\

vCONSTRUCTION OF SIMPLE THEMES

I. BEGINNING THE SENTENCE

I N the first chapter. 'The Concept of Form" il was slated that a piece of music consists of a number of pans. They differ more or less in content, character and mood:in tonality, size and structure. These differences permit present31ion of an idea fromvarious viewpoints, producing those contrasts on which variety is based.

Variety must never endanger comprehensibility or logic. Comprehensibility requireslimitation of variety, especially if notes, harmonies, motive-forms or contrasts followeach other in rapid succession. Rapidity obstructs onc's grasp of an idea. Thus piecesin rapid tempo cllhibit a lesser degree of variety. . .

There are means by which the tendency toward loo rapid development, whIch ISortCIl the consequence of disproportionate variety, can be controlled. Delimitation,subdivision and simple repetition arc the most useful.

Intelligibility in music seems to be impossible without repetition. While repetitionwithout variation can easily produce monotony, juxtaposition of distantly relatedelements can easily degenerate into nonsense, especially if unifying elements areomitted. Only so much variation as character, length and tempo required should beadmitted: the roherence of motive-forms should be emphasized.

DiKretion is especially necessary when the goal is an immediate intelligibility. as inpopul:u music. However, such discretion is not restricted to popular music alone. Onthe contrary. it is most characteristic of the manner in which the classical mastersconstructed their forms. They sought a 'popular touch' in their themes, this being theslogan under which the 'ars nova' of the eighteenth etntury detached itself from theshackles of the rontrnpuntal style. (Thus. Romain Rolland, in his Musical Journq.quotes the German theorist, Mattheson, in his Vollkommt'nt."r Kapre,lmi'isler (173.9)as saying that in the 'new style' romposers hide the fact that they wnte great musIc.'A theme should have a certain something which the whole world already knows:)

THE PERIOD AND THE SENTENCE

A complete musical idea or theme is customarily articulated as a period or a sentence. These structures usually appear in classical music as parts of larger forms (e.g.as 11 in the IIMI form), but occasionally are independent (e.g. in strophic songs).There arc many different types which are similar in two respects: they centre arounda tonic, and they have a definite ending.

1n the simplest cases these structures ronsist ofan even number of measures, usuallyeight or a multiple of eight (i.e. 16 Of, in very rapid tempos, even 32, where two orfour measures are. in effect, equal to the content of one).

The distinction between the sentence and the period lies in the treatment of thesecond phrase, and in the continuation after it.

TIlE BEGINNING OF THE SENTENCE

The construction of the beginning determines the construction ofthc continuation.In its opening segment a theme must clearly present (in addition to tonality, tempo~nd metre) its basic motive. Thc continu:nion must meet the requirements of corn·prehensibility. An immediate repetition is the simplest solution, and is characteristicof the sentence structure.

If the beginning is a two·me-15ure phrnse, the continuation (m. 3 and 4) may beeither an unvaried or a transposed repetition. Slight changes in the melody or harmonym:!y be made without obseuring the repetition.

lfIuslratiol/s frolll ,hc liter{/fure)

In E1l.s. 58d, 59/and 6Oc, simple repetition arrears with little or no change whatsoever. In Exs. 58e and g, although the harmony remains the same, lhe accompaniment is slightly varied and the melody transposed. In Ex. 58i the lower octa\'C is used.In Exs. 59d and g the melody only is slightly varied. In E1l.. 61c the second measurcof the SttOnd phrase ascends in conformity with the progress of the harmony towardsIll. Ex. 530 presents an otherwise unvaried transposition to III (the relative major).I.e. a sequence. Ex. 570 is sequential in the melody and partially sequential in the;Icoompaniment.

TilE DOMINANT FORM: TIlE COMPLEMENTIIR\' REP(TlTlON1

In many classical examples onc finds a relationship between first and second phrasesimilar to that of dux (tonic form) and comes (dominant form) in the fugue. This kindof repetition, through its slightly contrasting fonnulation, provides variety in unity.

In the repetition, the rhythm and contouf of the melody are preserved. An elementof contrast enters through the changed hannony and the necessary adaptation of themelody.

In practising this type ofrontinuation the tonic form may be based on: I, I-V,I-V-I, I-IV or possibly 1-11. In these simple cases the dominant form will conlrastwith the tonic form in the following manner:

, Exs. 52-61 at (nd of Chapl(r VIII, pp. 63-81.• This is one or many ( ....mplcs of)l\( difflCUllies 3sso;;:ial(d with 1()OSoC I(rminology. Tu//ic ;·u,';tnr ~nd

d//m'''''''f ~rsion would be dcarc:r and morc: pro:"i"", but Schoen!xr8 prer(rrOO to u-e Ih( morc: ramili'lrlerms (Ed.).

• • ••••'••••~ .,••~~~cr'

CONSTRUCTION OF SIMPLE TlIEMES (I)

£1".37

~PV; if,P

iT' V I

El". 88

le!I v v I

10t::1::::;M:j. - . .

Dominonl form

VV-IV-I-VV-IV-I

CONSTRUCTION OF THEMES

Tonic form

II-VI-V-II-IV1-11

JIIU$lrotiolls from the Iil('rtltl"~

In Ells. 350. band 53b. the first phrase employs only 1 and the second phraseonly V.

The scheme I-V (tonic form), V-I (dominant form) can be observed in Exs. 52band c. Compare also, among Beethoven's works, the Piano Sonata, Op. 31/2-11I (four.measure phrases); and the String Quartets. Op. 59/2-111 and Op. IJI-IV. The melodyis modified only enough 10 conform with the harmony.

The tonic form ofEK. 36 is based on I-V-I; the dominant form on V-i-V. In Ex. 37the dominant form includes some passing harmonies. In contrast, the passing harmonies in the tonic form of EK. 38 are not mechanically preserved in the dominantform. But in EK. 39, where tbe tonic form consists of I-IV, the dominant form consistsh:lsically of V-I, though more elaborate part-writing disguises il.

COMMENT ON EXAMPLES

The tonic form (m. 1-2) of Ell.. 40a is followed (m. 3-4) by a dominant form inwhich the melody follows the contour of the first phrase uactJy. In EllS. 40b and cother dominant forms are shown in which, while the rhythm is preseryed, the contouris treated more freely.

In Ell. 41 the dominant forms are varied more than the harmonic change requires.In Ells. 41b and c the tonic form is based on four harmonies, which makes a trueanswer difficult. To answer literally a tonic form wilh too many harmonies is impracticable. Here, only the main harmonies, I-V, could be answered, wilh V-I.

It should be observed that even in these short passages, a definite and regularaccompaniment is employed to animate the harmony and to express a specific character. Consistency in the application of accompanimental characteristics is a powerfulunifying factor.

22

In the last two cases, simple rc\'crsal of the harmonies is not impossible; but theV-I progression is preferable: bttause it expresses the tonality more clearly. Thecndingon J preceded by V is so u~fullhat it is oftcn applied when, for example. Ionic form is1-11, I-VI orcvcn I-Ill.

CONSTRUCTION OF THEMES

CONSTRUCTION OF SIMPLE THEMES

2. ANTECEDENT OF THE PERIOD

ONL ya small percentage of all classical themcs can be classified as periods. Romanticcomposers make still less use of them. However, the practise of writing periods is aconvenient way to become acquainted with many technical problems.

The construction ofthc beginning determines the construction of the continuation.The period differs from the sentence in postponement of the repetition. The firstphrase is not repeated immediately, but united with more remote (contrasting)motive-forms, to constitute the first half of the period, the amecedenl. After this conlrast repetition cannot be longer postponed without endangering comprehensibility.!Thus the second half, the cOl/sequefl/, is constructed as a kind of repetition of thcantccedent.

In composing periods a practice form will be useful. It should consist of eight mea'ures, divided into an antecedent and consequent of four measures each by a caesurain the fourth measure. This caesura, a type of musical punctuation comparable to acomma or semicolon, is carried out in both melody and harmony.

In a great majority of cases the antecedent ends on V, usuaJly approached through~I half or full cadence, but sometimes through mere interchange of I and V. Antecedents which end on I also exist.

The consequent usually ends on J, V or III (major or minor) wilh a full cadence.Although the consequcnt should be in part a repetition of the antecedent, the cadence,al least, will have 10 be different, even if it leads 10 the same degree. Generally, one ortwo measures of the beginning will be retained, sometimes with more or less variation.

VI

1 The real purpose of musical construction is not beauty, but intelligibility. Former tlleorisls and aesl!leti.uans called such forms.n tile period symrmlrical. The term symmelI')' has probably been applied 10 musichy analogy 10 the forms of Ihe graphic arts and architccture. Rut lhe only really symrru.:lrical forms in musk:me the milTor forms. dcrived from rontrapuntal music. Real symmctry is not a principk or musical construclIon. Evcn if thc consequent in a period repeats the antecedent strictly, the struclurecan only be called 'Quasi_~)mlnetrical'. Though Quasi·symmetrical construction is used c~lensivcly in popular music, Ihal beauty canniSI wilhoul symmelry is proved by a areal many <,;.]i'lC$ of asymmelrical construclion.

ANALYSIS OF PERIODS FROM BEETHOVEN"S PtANO SONATAS

Op, 2/1-11, Adagio. The antecedent ends on V (rn. 4); the consequent on I (rn. 8).The harmony of the antecedent is a mere interchange of J and V; the consequent ends

vv

Ex.41(From E~ 10)

.~)~~~~~~~~

I An ending on a strong beat is called 'masculine', and on a weak beat. 'feminine'. Too frequent use ofthe same kind of ending is often monotonous.

• Exs. 42-S1 appear at end of Chapter VII, pp. 32-57.

ANALYSIS Of OTHER ILLUSTRATIONS fROM THE LITERATURE

In Ex. 43 Bach's contrapuntal movement often conceals the caesura. But the periodlike repetition of motive-forms is evident. While one of the examples (Ex. 43b) endson III (the relative major), three others are treated similarly 10 the Dorian mode;i.e. Exs. 43c and e reach the dominant through a quasi-Phrygian cadence, and Ex. 43dmust be classified as having a plagal cadence, though the upper voices, astonishingly,express the authcntic cadence. Such a procedure is only justified by the motion of

independent parts.In the Haydn examples, Ex. 44, the caesura (always on V) is somctimes approached

lhrough mere interchange,sometimes through half cadences, and occasionally throughfull cadences. Exs. 44a, e and I are irregular, i.c. they consist of 10, 9 and 9 measures,respectively. The structural meaning of the extensions is indicated. In all the examplesm. 3--4 differ significantly from m. 1~2. Even in Ex. 44!, using continuous sixteenthnOles, the figuration and the harmony of m. 3--4 arc elearly differentiated. Observeespecially the relations and variations marked with brackets.

In some of the Mozart examples, Ex. 45, the repetition at the beginning of tile

with a full cadence. The upbeat, which is twice varied, and the feminine cnding' In

m. 2, 4 and 8 are unifying characteristics of this melody. It is significant that the melodicapproach 10 a climax in m. 6 is supported by more frequent changes of the harmonyand the increasing use of small notes. The downward movement after the climax is

also significant.Op. 2/2-IV. The caesura on V is reinforced by a half cadence in m. 4. Observe the

contrast between the first and second phrases. The consequent deviates harmonicallyin m. 6, ending with a full cadence on V (m. 8), as ifin the key of the dominant. M. 7and 8, through remote variation and richer movement, produce the necessary intensi

fication of the cadence.Op. 10/3, Mcnuclto. The antecedent and consequent consist of eight measures

each. In the firSl four measures of the consequent, the melody and harmony of theantecedent are transposed a note higher, without any olher variation.

Op. 10/3, Rondo. This period consists of nine measures, the irregularity resultingfrom the five measure consequent. The contrast in ffi. 3--4 makes use of a specialdevice, a chain-like construction. Ex. 42at shows that the end of each motive-form isthe beginning of the next; they overlap like the links of a chain. The consequentintroduces (m. 5--6) two ~equences of the motive, in place of the single repetition inlTI. 1-2 (Ex. 42b). A premature ending in the seventh measure is evaded througha deceptive cadence, and completed with a varied repetition ending in m. 9.

CONSTRUCTION Of TilE ANTECEDENT

In the opening section of lhe sentence, m. 3--4 are constructed us a modifiedrepetition of the first phrase. The antecedent of the period introduces a new problem.Since the consequent is a kind of repetition, the antecedent should be completed withmore remote mOlive-forms in m. 3--4.

As a consequence of the 'tendency of the smallest notes',t one mayexpcct an increaseIn smallllotes in the continuation of the antecedent. This can be observed in tbe third(~ometime~also in the fourth) measures of Exs. Ma. b, c, d, g, k. 45a, b, c, d,i and 46<'.

But the Illcrease of small notes is only onc way of constructing m. 3--4 as a contrastII1g, yet coherent,eontinuation ofm. 1~2. In Exs. 44!, 11, i,i, I, 45f, 460, dJand 47b, c,rI. c. the coherence is more evident than the contrast, which consists merely ofa changeof register, direction or contour.~ coherent contrast can also be produced through a decrease of smaller notes, in

which case the motive-form appears to be a reduction (Exs. 43a, 45i, 46g).Such a decrease is often used to mark melodically the ending of the antecedent, the

caesura. Exs. 44a, d, g, h, i, 45b, 46e,f,g and 47a, d show this usage. Generally,thc caesura is supported by a contrast in the contour, which often descends below~he register of the beginning (Exs. 44c, d,!, k, 45g,i, 46e. 47a). Frequently the caesuraIS approached by receding from an earlier climactic point, as in Exs. 44a, i, i, k, 45n,h, (',fand 46<"1, b, e.

I 1llc smallest notes in any ~gmenl of a pi~. e,'en in " motive or motive-form h"ve an influenee onthe continuation which c"n be compared 10 thc momentum of acceleration in a f"lh~g b<xIy: thelonger themo,emenl lasts. the f;lS~er it becomes. Thus. if in the beginning only One sixtocnth'l1ote is "lied, very soon.In mcreasong number WIll appear, growing often into whole passage$ of sixteenths. To restrict this tendency"r the smaltest notes reqoires ~pccial care.

CONSTRUCTION OF SIMPLE THEMES (2) 27

consequent is slightly varied. In Exs. 45e and!, the inversion of I is used; in Ex.45aIh.c whole consequent is shifted to the lower octave; in Ex. 45c the simple doubling,)1 the bass produces an effective variation.

The Beethoven examples, Ex. 46, are chosen principally from the viewpoint ofcharacter. In .Exs. 46b, d and!, the consequent is built on the dominant. How manyl:lflatlOns a slllgle rhythm can undergo is evident in Ex. 46d. Note that in both ffi. 6;lI1d m. 7. two harmonies arc used (intensification of the cadence through concentralIOn). In Ex. 46e both the antecedent (five measures) and the consequent (seven mea~

\ures) show remarkable irregularities.Among the Schubert examples, Ex. 47, two (Exs. 47b. c) show how beautiful a

I~lc!odY can be built .from variations of a single rhythmic figure. Since rhythmictcatu~cs are more eaSily remembered than intervallic features, they contribute moreeffectively to. comprehensibility. Constant repetition of a rhytbmic figure, as inpopular mUSIC, lends a popular toucb to many Schubcrtian melodies. But their realnobility manifests itself in their rich melodic contour.

CONSTRUCTION OF THEMES26

" CONSTR UCTlQN OF TIt EM ES

When the coherence ~tween the basic motive-forms and the more remote derivatives in m. J-4 is not quite obvious, a connectil'/' may bridge the gap. One of thefeatures, oflcn the upbeat or a preceding moti\'e-form, is used to join them. (Exs.44d, I, 4Sc, J. g. 46t', 47(/). But abrupt juxtaposition of contrasting forms need notnecessarily produce imbalance (Ex. 450).

As harmonic basis for an 3nlece<!.cnt, one can use progressions like those ofExs. 43to 51. Movement of the harmony in equal noles (i.e. regular change of the harmony)supports unity because it is a primitive kind of 'motive of the accompaniment'.

It should not be forgotten that onc purpose of constructing motive-forms frolll abroken chord (Exs. 5-11, 17-29) was to assure a sound relationship between melodyand harmony. To mllke many sketches of motive-forms, built from broken chords byvariation, remains a valuable method of deriving well co-ordinated materials.

Onc may acquiesce to the 'tendency of the smallest notes'. But too many small notcsmay produce a crowded effect. On the other hand. in masterpieces one mectscases likelhe extreme rhythmical contrast bet ......een first and second phrases in Exs. 450 and J.In other Mozan examples (Exs. 45b. g). the co-ordination of the small notes ......ith thehannony. as ancillary notes. is of a perfection which no beginner dare hope for.

Continuous and thorough study of examples from musical literature is essential.There are many melodies whose compass is very small (sec Exs. 45;. 5Oa. b). Some

limes when the antettdent remains within a fifth (Ex. 47e) or a sixth (Ex. 46d) theconsequent ascends to a climax. But melodies whose compass at the beginning is verybroad (Exs. 44a. c. d, 450) arc likely to achieve balance by returning to a middleregister. All these examples show that much varielycan be achieved within a relativelysmall compass. though the extension of the compass is often a defence againstmonotony.

Envisioning a delinite character helps to stimulate inventiveness. The accompalliment makes important contributions to the expression of character. Such features asdilferentialion between detached and legato notes (Exs. 44J, 47c. 480. 500, e); restswhere harmonization is not required (Exs. 35. 38. 44h. 4611); unharmonized upbeats(Exs. 440. g. 45[. 4611. J. etc.); semicontrapuntal treatment of middle voices (Exs.41b. Mg. 450, 48b. 51/); afterbeat harmony (Exs. 44r. d, 45d. 46d• .5Ot'); and specialrhythmic figures (EJls. 46), 47b, 490. 500, 51f) should be employed from the verybeginning.

It is difficult 10 reconcile a complex accompaniment with good piano style. Writingfor the piano should ignore. as much as possible. the existence of lhe pedal, Le. every·thing should be within easy reach of the fingers.

One must beware of (I) imbalance through overcrowding. (2) destruction of thecharacter and (3) obscuration of the harmonic progression. Fluent part-writing inthe accompaniment does not endanger the clarity of the harmony. But control ofthe root progressions is essential.

VII

CONSTRUCTION OF SIMPLE THEMES

J. CONSEQUENT OF THE PERtOD

rlt E consequent is a modified repetition of the antecedent, made necessary by the~cmote motive-forms i.n m. 3-4. If the period is a complete piece (e.g. children's songs)It must cnd (usually WIth a perfect authentic cadence) on I. If it is part ofa larger formIt may end on L V or III (major or minor).1~n unchanged and complete repetition is very rare. Even in the very simple cases

of Exs. SOb. (. and e. at least the last measure is modified. Usually. the introduction of;1 full cadence requires earlier changes. In Exs. 45;, k. 400. g and 500 lhe dcvi:l1ion ofthe harmony occurs in the seventh measure; and in Exs. 44; and 47(". t:. in the SiXlhmea~ure.

V:lriation of the harmony can slart as early as the first measure of the consequent.In Ex. 45fthe variation consists in the use of inv(:fsions of the same harmonies. Theconsequent may even begin on a different degree. For instance. in the Menuetto ofI.lcctho\cn's Op. 10/3. m. 9. it starts on 11, as a sequence of the antecedent. In Exs.44b and 46<1, it begins on V. The harmonic variation in m. 5 of Ex. 47t1 is the beginning. of an enrichcd cadence.

Ml:LODIC CONSIDERATIONS: ('Al>£:"CE CONTOUR

V<lricty needs no justification. It is a merit in itself. But some variations in thcmelody are involuntary results of the changed harmonic construction. particularly ofthe cadcnce.

111 order to exercise the function of a cadence. lhe melody must assume certaincharacteristics. producing a special radt'/Ire COflfoll'. which usually contr<lsts withwhat precedes it. The melody parallels the changes in the harmony. obeying the ten\lcne) of the smallest notes (like an aculerando). or, on the contrary. contradictinglhe tendency by employing longer notes (like a ritardando).

Increase of smaller note values is more frequent in cadences than decrt:ase. Asl'\.:Imples of rhythmie incre3se. $tt. in the Ikethoven Sonatas: Op. 2fl. Adagio. m.

, Somcl'mc~ major lit 0«:""" in" m"jor hy. In 8n:lhuV<:fl'~ Slrin!: Q":I'h:l. 01'. lJI-V. a IPhrni~n)1",1r,.,oJcn<:' lC:ld~ 10 a lm"jo,) Ill. tn h" Sl,mll Qu;orl". Op. ISI~. Var~,hon 4, 3 run .:alk'>«, wads 10:l,,,,,~~r).11I In m. B. Endinll on minor v. in a minor ~(y. i~ illu.,ratcd in E~. 46.4-. In two (xlraordi""ty Ca~'Ihe :>lflng QuarlelS. Op. ~9i2-1I1 anoJ Op. 132_V). &-clhovcn even makes use or VII \dom;na~t of rclai've''','J"q in mino,.

I Thc rJllid <levdopmcnl of h;lrnlony liocc lhc IKginninll of lhe nir\C:l~nlh ccnlUry h~s bee" the grC:'1"I"'aclc lu IM :icccptJocc of cn:ry ne.... con'po~r r.om Schubert 0". Frcqucnt <levialion from lhe IOlllC'C1;'"'' "'10 more Or k:$s fore'IJI rcgions ~mcd 10 ol:»lrucl unity ~n<l inlel"l,b,lity. Howcver. thc fnO!Ot.,d"'Jnced mind is still ~ub:jo;t IQ hum.,n limil~I'Ons. Thus compo!i<:fS Qf th's ~Iy"'. "'SI",cI,"e1y fechnl: lhe,1..nl!C" of incohc.c~. counter.lClc<! the tension in 0"" pl~ne (Ihe complcJl hJ'mony) by simplifoclllion on..nntt:e. p~nc (Ihe fllO('V'JI aoo rhychnl,C constnJl;1ion). ThIS pe.haps all.o cxplluns ,he; unv:..icd fCpelil>(ln~

.",.1 frequcnt 5eqUCfll.'eS 0( WaJllC', 8rucl;ncr. Oeb~y. ~. Fr.lnc.. , T..hJi"o's1-y, S'belius and many",he",.

To the conlemJlOt'3~or Gusta" 1>1Jhlc., M:u Rcgcr. Richa.d Smu,ss. MJunce Ravd. CIC.• far.rod\",gh..,mony no klnl!C" "",riO'USly enl,lJnF'eoJ comprehensibll,ly. and tod.<y-~"~n popuLi. eomposers m:I"c ah"nr: rrom it!

the immediate continuation. The deviation in m. 3 toward Ep is surprising. While £,mighl be the dominant of the mediant region (relalive major), il is actually treatedlike a tonic on VII. But in m. 7-8 13rahms finally identifies m. 1-2 and 5-6 as pertainmg 10 ("-minor, or, more accurately. 10 the "-region off-minor. I

In Ex. 51(" a repetition (m. 11-32). unchanged in melody and harmony, is varied by\upplying a quasi-contrapuntal treatment of lhe accompanying lower voices.

The construction of Exs. Sld and (' will be clarified l:lIcr (Chapter XV). Obsen;elhe use ofapedalpoim in Ex. Sld, at the beginning {rn. 1-2)and at the end (m. 10-14).

Though the pt'dal point is often used in maslerpil'CCS for expressive or pictorialpurposes. ils real meaning should be a constructive one. In lhis sense onc finds it atthe end ofa Irnllsition or an elaboration, emphasizing the cnd of a previous modula·lion and preparing for the reintroduction of the tonic. In such cases the effect of,1 pedal point should be one of retardation: il holds back the forwll.Td progress of theharmony. Another constructive use of such retardation of the harmonic movement1\ 10 balancc remote motival variation (a method paralleled by the balancingofcenlrifug;!l harmony with simpler rnolival variation). If no such purpose is involved, a pedalpoint should be avoided. A moving, melodic bass line is always a greater merit.

In Ex. SI/Ihe tendency of the smallest notes accounlS for a variant in m. S. Therhythmic figure '/I' is shifted from the second beat 10 the first bea\. In consequence,an almost cOlltinuous flow of eighth-notes prevails.

JO CONSTRUCTION OF THEMES

6-1; Qp. 2/2-IV, m. 1; Qp. 22, Menuetto. m. 7; Ex. 46g. m. 7-8. Sec also Exs. 44b.m. 1; 44i, m. 1; 47c, m. 6-7: 490, m. 1.

An unusual example of rhythmic decrease is shown in Ex. 46h, m. 7. Other examplesinclude Exs. 44j and 46; (very conspicuous). Thc two cases in Ells. 441 and 470 areremarkable because, instead ofa rhythmic decrease, a 'written-out ritardando' appearsas an extension.

The melody in the cadence commonly reduces characteristic features (which demand continuation) to uncharncteristie ones. Illustrations of this can be found in agreat many examples. Compare, for instance, m. 1 ofbs. 4Sc and/with their res~tive m. 1-2. In both cases the characteristic intervals are abandoned, or combmedin a different order, and in Ex. 45c the eighth-note mo\'ement stops entirely with thethird and founh beats.

Ifthereis a climax the melody is likely to recede from it, balancing the compass byreturning to the middle register. This decline in the cadence contour, combined withconcentration of the harmony and the liquidation of motival obligations, can bedepended upon to provide effective delimitation of the structure. Sce, for example,Exs. 4Sf. g.

It H YTH Mle CONSl DEltA TlONS

Since the consequent is a varied repetition of the antecedent, and since variationdoes not ch::mge all the features but preserves some of them, distantly related moliveforms might sound incoherent.

TIlE PRESERVATION OF THE ItIlYTIIM ALLOWS EXn"NSlVE CllANGES IN TilE MElOIJIC

CONTOUR.Thus in Ex. 47b the consequent preserves only onc rhythm, abandoning for the

sake of unity even the slight variations in m. 2 and 4. This rhythmic unification permits far-reaching changes of the melodic contour in slow tempo, and promotescomprehensibility in rapid tempo. Sce also Ells. 45a,f, 4&1,j.

COM~IENT ON P[RIODS RV ROMANTIC COMPOSERS

Some of the classical examples of Exs. 44-47 deviate from the eight-measure con·struetion. Such deviations can also be found among the examples from Mendelssohn(Ex. 48) and Brahms (Ex. 51). To control such divergencies requires special techniques of extension, reduction, etc., whose discussion must be postponed.

These examples show the various manners in which Romantic composers approachthematic construction. The examples from Brahms arc especially interesting becauseof their harmony. They differ from lhe classic examples in a more prolific exploitationof the multiple meaning of harmonics. Ex. Sla is an illustration. In m. 1-6 thereappear only a few harmonies belonging diatonically to [minor; bUl most of them(lll .) could be understood as Neapolitan 6'h of c-millor, 3n explanation supported by

CONSTRUCTION OF SIMPLE THEMES (J) 1I

32 CONSTRUCTION OF THEMES CONSTRUCTION OF SIMPLE T1IEMES (3) 33

'J. ft,lJT1' . J i

Phrlll:la.. Codnce,0V

'",

PERIODS

Ex.42Op.lll/a_rV • ~rJ?if

~ll'~

34 CONSTRUCTION OF THEMES CONSTRUCTION OF SIMPLE THEMES (3) 3S

v

., Shin!; QUHt~t.op.6!1'·1l

Adagio f ,...---:::"

OJ

v

,•.'.~

:~ .••

Ex.44a) HaJ"", String Quartet, Op.S4}1

Mu~d'o .'~ :I' r::: ,j,'

'~~'~

{~~~~Wd~-~_~,~~~''''''~....~..~~~~

CONSTRUCTION OF THEMES CONSTRUCTION OF SIMPLE THEMES (3) 31

•

elh"UI" 'ba",••r41•••U....~ . .1

rn

J) Striq Qgartd,O,.",rt·rv. r

~hU.r culuc. V

.' i,."""l tr'

•

•" ..I_III••,..-.tallot.,."...... er ..... ,

~•

le::r:c:r::r="'!' IT V 1

C) 'binl!: Qu.IoI,Op.14/J-mNuutt. •, ,

38 CONSTRUCTION OF THEMES CONSTRUCTION OF SIMPLE THEMES (J) 39

r) Pi ...o Soa.l. I.V.2I3-nf A,,,lu{e 11 m...... 2)

I II V

<pi.od!. lnaerllo.

Ex.45.) .I1o:~rl. ri,M Son. to K .V. 219-111

AllegrQ •.............. ,. ".__ ...~.....~." 11

\, • •................. ..............• f( " _.,.

~ IIV_

~.It cadenc.

I

b) fiano Sonal. ICV.2!l-1

':.g:..,. ~,---~

1~~1,

40 CONSTRUCTION OF THEMES CONSTRUCTION OF SIMPLE THEMES (3) 41

x··········w .-. 4 ".~...... "...... .. S

..,

h) Piuo S.nab K:V. 311-I!

~::e:r~

~) Pl&"o Sout. X.V. 310-UAlldut" eallfabilt! """ e.preniou:

~, ~ It, r I I

~> Ii half

4J

v,,

CONSTRUCTION OF SIMPLE THEMES (3)

'1 SlrinJ! Trio Op.SAt,,!;,·

d) Std"lI" Trio Op.3-U('"'Kk rhythmic rllf~r" In ..onifoM variation')

A~J",,1f: 1 .2 ~~~i"~!,!~~~'ili~!:if,~§~

,.~

~. .

CONSTRUCTION OF THEMES

E:x.46.) H££THOI'~:fIi S.pteIOp.20-IVT~e,". CO~ ud.. ion"

VIol I. f J

42

"CONSTRUCTION OF SIMPLE THEMES (J)

Il Shl,,&" Qur'" Op.~'/HlI

~O

-- ry;¥fgI

J) String Quartot Op.18II-UT, Seh...o

I. . . . .

I.. ~

•

•

•

•

v

CONSTRUCTION OF THEMES

8) Slri"$" Trio Op.1AllrGrd/Q o/la. l',,("CCQ

fl SI.l~1: Trio 0,.'SCIII':1I10Aflr&ro -r"II/1, . .

44

47

.,,rf! ~

=-•..

CONSTRUCTION OF SIMPLE THEMES (3)

d Plano Sonata Op_~J'IV

ROI'DQAlI'C,D m"d.rat", ,

.l Pi••• Souu Op.lft·l

A/l.~r•••" •••1"-,

1 '

i..... ""er> ritortl.

,

, ! .-Fine" ut .h........

~ n,l=",J~J~~~ - ==" I I

CONSTRUCTION OF THEMES

.J Pi t. op,n-IIr f.

I~~,.

E.1.47a) <I>'(:HU8ERr, ]';ano Sout. op.n-I

MrxI~r.lt/ ,

46

"

•,,

~ (J)

CONSTRUCTION OF SIMPLE THEMES (3)

c) S~I"J.·., op.~1IJ

~/''Kro ossa;

d) l'ut.I'ui.clt..~ (;",..1./1•••, op.75I~

Allet:ret{o -0" Iropp" (2 II'lU•. ' \)

p

p

48 CONSTRUCTION OF THEMESEx.48.l JltElt'DELSSOHN FM Hn-!~I, op.gfS

A"tIn,""

"

, ,

f, r I pr------- p~

>

~, ::::-

'", " "

CONSTRUCTION OF SIMPLE THEMES (3)

Ex.49.) CHOPIN Nocturne Op.32!l

L~"fo

b) ~octuru op.37flA"da"te Itltteuto

jI.. "VII ====--

, ,

CONSTRUCTION OF THEMES

, r,---r ' f'--'f ' f'---f '

.,

"CONSTRUCTION OF SIMPLE THEMES (3)

l~. v»

•,CONSTRUCTION OF THEMES

,~l SotluTO. Op.U}\L~.,o ..,.

EI.50_) SCHlfJ/A'OI' J.llro .. ,iO. dj. J'r~". S.'ff"'R.~Ie4

I• •

"

v,v1"•

'"lil In.,..ia.at nr'." I'T

CONSTRUCTION OF SIMPLE THEMES (3)

,

'" ,

, ";;:==

~

>V • V .. V

~ r r

."-1::

" • V

Do..lun~ ..,ion: • 'I " 'I Vde.

~

~

<?S'

'.

CONSTRUCTION OF THEMES

Er.51a) /lWAHII!l 51"11( Q...lol O,.!III-llI

AllFf:Y' ••fto .",J.rat• • u ....fl.'-,--_.- 'e-~-~~~

CONSTRUCTiON OF THEMES CONSTRUCTION OF SIMPLE THEMES (3)

f) VloUn Sonat. Op.IOO·Jl

Vill/'u

,--~: r'~ •p,. • , . ---=. ..P "'0/10 I<GKi.~o

r r r /==--• ", " Vm '"

,

"

f{).....-...... =

4r r

P.rlo. of 6 mUSuc" «p..\od

,

.) Piano Trio Op_lOtA"dut~ crOZiiuo,

hs. 520 and b. the two-measure phr:lses are reduced or condensed l (in rn, 5-6) toonc measure; and in Ex. 52c, four measures .are condensed to two measures (m. 9-10and 11-12). This procedure sometimes results in still smaller units: in Ex. 52h ahalf-measure; in Ex. 52c on~ measure.

The end of a sentence calls for the same treatment as the consequent of a period.A sentence may close on I, V or Ill, with a suitable cadence: full. hair. Phrygian,plagal; perfect or imperfect; according to its function,

COMMENT ON EXAMPLES

Exs, 54, 55and 56 arc based on the broken-chord form, Ex. 7b. By progressive variation (Exs. 54a, b. c) a motive-furm is reached which can be used to build sentences of~harply contrasted character. The endings lead 10 V and III in major; to v and V inminor, To indicale how easy it is to change the cadence region. even at the very end,alternatives are added for Exs. 560 and b, ending in the region of the relative major(study also the Trio of Beethoven's Op. 28-111).

Sequcnce-like proceduresl are very useful in the continuation of a sentence. Thepattcrn for such sequence: treatment is usually a transformation or condensation ofpreceding motive-forms. Assuming a correct harmonic connexion, the pattern maybegin on any degree.

The quasi-sequential repetitions in Exs. 54. 55 and 56 are morc or less frec transf/O<;itions of the pattern a wltole- or half-tone up or down, except in Ex. 56b wherethe interval is a fourth down.

, Rcduction Jllay be aa:OJllpli~ht:d by merely omllling a part of the lTlO<k:l. Condensation impJic~ com_prC!lSUlllthc contcnt of Ihc 1I1o<Jcl. whercby evcn the order of lhe fcatu",.. may be :wmewhat chanllt'd.

, A J'rqu~nct:, ill its strict"'t lne"ning. is a repeti/ion of a ,;cgmcnt or unil in its entirety, induding thehurmony am! lhe a('(;(lmpanying voices, rransp<J.ed 10 a""tlre' <kg.'ce.

A loCquenoe Can be executed WIthout using other than diatooK: tones: In such e.tSC$. the harmony remains'~"nltiJICtal', i.e. «ntred aboul (he Ionic rcgion. Diatonic sequences expl'CSS Ihe IOI1;lJity clearly and do nOtc<>d~n~r ""'ance in the oonhnuatlOfl.

When SlIwilUICS nlletul' or 'chromatic' cootds) ~re usrd, Ihc tcndency of the turmony may bocotl'le·c.."'ltlfu~r---m:lY produa: moduLmons. 10 ""Iann whoch becomes ~ prob"'m. SOI)!,hlulcs should be usNI'flIn:mly 10 reinforce the 10&1(" or I~ prQCl"CUlO", carefully observing lhe quaSI-melodic rUnc1ion of lhe....bslllull: Iones.. For CJl:Impl.:. a WWilUlcd major thord tench 10 lead up"'':lrd, while a substiluled mn....rIhmllea<h dQwn_

The p;ll!cr" for:t sequenn mu" b.: so bulh. ha.rmOrlle::iIly >InJ. mclotliclty, that It tnlrotlucn lhe <!ecru 00..hl\:h the sequence,s 10 be"n, and provodcs a )tTIOQjh mdodte conncxion.~uenccs III minor arc even more apt to prod~modUlatIOn than in m3.jor, bocau~ or the '""fling rornli

of lhc minor ..:ale. In octual pr.>etKe, K'QUC'!"tCCS ,n mlllor are most oftcn buill around lhe natural or tJc:5ocl:nd.,n! form; but the .\It3.tcgie teintrOOUC:lion or Ihc lead,ng_tone is uloCd 10 pre>'Cnt premature mOOulation.

SC'lucntial treatmelll 's oot allll:lYs compltlc. tt may b.: applied 10 cither m.:lody or h:lmlOny alon.., theremalni"g c1",.ncnl bdnll more or Icss freely varied. Such e<lses may be calkdlll<Xlijied or partialloCquc""CJ.I" Ulh<:r cases thc general charactcr of a lranspo'lCd repetition may be present. though without ltleral Hanspu.il,on of any clement. These instances, and Olhers in~ol"inll ~ariation of somc features, may be lkSl;ribl:.Ja. QUD,i-U'Qut>miDI.

"CONSTRUCTION OF SIMPLE THEMES (4)

VIII

4. COMPLETION OF THE SENTENCE

CONSTRUCTION OF SIMPLE THEMES

A PIECE of music resembles in some respects a photograph album, displaying underchanging circumstances the life of its basic idea-its basic motive.

The circumstances which produce these v3rious aspects of the basic motive-itsvariations and dcvclopmcnls-derive from considerations of variety, structure, expressiveness, clC.

fn contrast 10 the chronological succession in a photograph album, the order ofmotive-forms is conditioned by the requirements of comprehensibility and musicallogic. Thus, repetition, conlrol of variation, delimitation and subdivision regulatethe organization of a piece in its entirety. as well as in its smaller units.

The sentence: is a higher form of construction than the period. It not only makesa statement of an idea. but at once starts a kind of development. Since developmentis the driving force of musical construction. to begin it at once indicates forethought.The sentence form is much used in leading themes of sonatas, symphollies. etc; butit is applicable also to smaller forms.

Thc beginning of the sentence (Chapler V) already ineludes repetition; hencc, thecontinuation demands more remotely varied motive-forms. In masterpieces this hasgiven rise to a greal variety of structures, some of which will be discussed later. Hutthere are also a great many examples similar to the scheme that will serve as a practiceform.

The practice form will consist, in the simpler cases, of eight measures. of which thefir:.t four comprise a I>hrase and its repetition. The technique to be applied in thecontinuation is a kind of development. comparable in some respects to tlte condensing technique of 'liquidation'. Development implies not only growth.augmentation, extension and expansion, but also reduction. condensation andintensification. The purpose of liquidation is to counteract the tendency towardunlimited extension.

Liquidation consists in gradually eliminating characteristic features. until only uncharacteristic ones remain, which 110 longer demand a continuation. Onen only residues remain. which have little in common with the basic motive, In conjunction witha cadence or half cadence. this process can be used to provide adequate delimitationfor a sentence.

The liquidation is generally supported by a shortening of the phrase. Thus in

60 CONSTRUCTION OF THEMES CONSTRUCTION OF StMPLE THEMES (4) 61

Th~ pattcrnneveal various ways of combining and transforming preceding motiveforms. Only in Ells. 54d and 55b is the order the same as in the first phrase. In Exs.S4t!,f.lhe order is reversed ('b'-'a'). In Ex. 56. only ob' and 'c' arc used. Note Ihat thepattern in Ex. 550 begins with. a transposition of that feature which ended the preceding phmse ('cl". m. 8) and associaies it with 'b' in the form used in m. 3 and 7.Obsen'c also the lrealmenl of the motive of the accompaniment. 'c', which (as shownby the analysis in terms of 6/4 metre) is shifted from the weak 10 the Slran!! measurein m. 9-10.

Illustrations from Ihi' IiferalU'~

Among Exs. 5J.--6I, from Bach, Haydn. Mozart. $chubcrl and Brahms. there arccases in which the scheme, tonic form-dominant form, is replaced by a differentkind of repetition (KC Chapter V).

In almost all of these the continuation arter the repetition of the first phrase iscarried out with condensed phrases giving way to a cadence contour, described in thepreceding ehapler. Generally these closing measures employ only residues of the basicmotivc.

As a practice form is only an abstraction from art forms, sentences from masterworks orten differ considerably from the scheme. Among the illustralions the mostobvious deviation lies in the number of measures-there may be either more or lessthan eight (or multiples ofeight). The beginningofMozart'sOverture to Thi'Marringi'of Figoro (Ex. 59i) is only seven measures.

A length exceeding eight measures is often caused by the use of remote motiveforms, whose establishment demands more than a single repetition: or by the con·nexion of units of unequal size (e.g. one measure plus two measures); or by insertions.

Ex 53b is such a case. The motive-form in m. 5, though based on the interval of athird, derives indirectly from the figure marked 'b', which could be understood as anembellished syncopation. This is a very remote variation, whose repetitions accountfor the length of twelve measures.

It is characteristic ofMozart's Rococo technique to produce irregularity within thephrasing through interpolation of incidental repetitions of small segments, residues ofa preceding phrase.

In Ex. 590, after the two one·measure phrases in m. 5 and 6, a segment of threemeasures (repeated with a slight variation) appears. The example could be reduced toten measures if m. 10-12 were omitted. Testing which measures could be omitted isthe best method to discover what causes the extension. Omitting m. 7-11 would rcducethe example to the eight measures of the practice form, indicating that these measuresshould be considered an insertion, from which the extension results.

In Ex. 59b, m. 5-6 could be omitted. l

, The lUC'ttSSion of IWO 6/4 chorlls in m. 7 anll 9 is mosl unu~ual. 0"" mil;hl suspect a mi~prinl for wch a

In Ex. 59c the omission of m. 7-8 reduces the ten measures to eight.Ex. 59d is more complicated. The end of this sentence coincides with (overlaps) the

beginning of a repetition. Nevertheless, it cannot be considered less than nine mea·sures. The extension is produced by a sequence in m. 6-7.

In Ex. 59". m. 5--6 are made up of remotely varied motive-forms, because of which:1 modified repetition follows in m. 7-1:1. Such extra repetitions are certainly consequences of the requirements of comprehensibility.

The ending (on VI) of Ex. 60a is unusual. Still more unusual is the anticipation ofVI (through a deceptive cadence) in m. 10. Were this not the work of a master onewould be inclined to call it a weakness. Certainly either of the two 3Iternati\'e versions.....ould be safer for a student. These last four measures make the impression ofcodellas; if Ihey are, the preceding eight measures might be considered a period. Butanalysis as a sentence is supported by the similarity of the two segmenls, m. 1-4 andm. 5 S. to tonic form and dominant form. This hypothesis would le3d one to expecta continu::llion of eight measures.

In Ex. 60c the beginning, on Ift-II, is remarkable. The Finale of Beethoven's StringQuamt. 01'. 130, begins similarly.

In Ex. 60e the (quasi·sequentilll) repetition ofa short segment (m. 7-12) and Ihecondensation in the cadence show a certain similarity to the practice form. Otherwise,the preceding six measures hllve merely an introductory character.

The first six measures of Ex. rofconsist of two units of three measures each, organi,...d similarly to the lonic- and dominant-form. These three·measure segments arc notproduced by reduction or extension,·but by quasi-sequential insertions, repetitions oflll.land .... 1

Omilling m. 7-11 and m. 13 would reduce Ex. roll to the eight measures of thepmcticc form. Howc\'er, m. 7-14 could also be considered as an independent additionof four measures with a varied repetition. Though 'as' is an augmentation of 'a', thl:phrase in m. 7-8 must be considered a remotl: variation. justifying the repctition.

The 3nal)'sis of Ex. 61a shows that the theme is less complicated than it appears atfirst i!lanc.:. (The theme or melody need not. of COUIU, always be in the highest voice.l\ccompanimC'nt and melody may exchange places in various ways. Naturally, the

""'''-~ "'~ lhal ,ndic:.IlW lxlowm. 6-7. Such a 1<caIO"l(1l1 ofa 6/40;hord would K:ln:cly be found d_~ inM"",rl- DUI ~incehe UKSlhe same 6/4 for:l c:ldef\CC 10 1{m. 25. 271.one must abandon the: idea 0( a misprint.M'~"n' or molo; or llIeniu,. il is hardly a nt<>del ror Ihe student to imitale.

, SChulxrl W"~s disl'nclly onc of Ihe: pionten in the field or ""m>ony. The: s,nlCuwrily or hi~ harmonic(..,110' o;~n I:..: ob1;erved in lhc: entlinlC or Ex. 6Ob. A. a varied repetilion or m. 1-8. m. 9-16 should end onI: bUl ,n'lr"d ItN: repelllion o;nll. on lhe: subdOOlinan" Thallhi, i, no "'caknc:s~ is evident rrom the ll:C:Ipilula.l'on. whi<;h ~13fl~ on lhe: subdomin;lnl (1Il'SIO;;lll or lhc: lonk) bUl o;nds on lhe Ionic, though a s1ri<;t tl1lnsrvsilion would havo; endell 00 A~. Thu~ the harmonicschenlf; is I-IV: IV-I. !rhe had U-Sf'<! the procedure orlhe rco;apl!ulaltOI1 in m. 15-16, the: c:,<!e:n<,.--c woulll have lell io m. 16101/.