ARMOR, September-October 1988 Edition

Transcript of ARMOR, September-October 1988 Edition

In our last issue, Major Mike Matheny began his story of the historical use of armor in Low-lnten- sity Conflict with his examination of the U.S. ex- perience in Vietnam. With this issue, he con- cludes the two-patter with a look at Soviet opera- tions during the eight-year-old war in Afghanis- tan. Did the Soviets capitalize on our successes in Vietnam, and did they learn from our mis- takes? What do we know now about Armor in LIC, the most likely battle scenario?

for which we do little training, is combat in and near citiis. In "Armor Takes Cologne," Major John M. House takes us along with the 3d Ar- mored Division on its mission to take the major city of Cologne early in 1945. This was a mission for which armored divisions were not designed, and one that flew in the face of the doctrine of the day.

In an associated story, Captain Andrew F. DeMario asks "When Will We Ever Learn?'. Europe is covered with forests and villages and towns of various size. Fighting in these environs will be the rule, not the exception. Because we do not train for heavy combat in these condi- tions, the author wonders if we are losing sight of the realities of armored offensive warfare.

Deception is a combat multiplier. A good decep- tion plan and operation can move enemy forces out of the way or in the wrong direction, force the enemy to throw his reserves into the pot in the wrong place and time, force the enemy to waste ammunition and other assets, and reap other benefits for the commander who pays atten- tion to deception. In "Voices in the Sand: Decep- tion Operations at the NTC," Captain George L. Reed outlines how to confuse and deceive the enemy with a little sleight of hand.

Another likely scenario for future battle, and one

Because training exercises rarely produce real casualties, problems associated with evacuating casualties do not rise to the surface. In "Medical Evacuation," CW3 William L. Tozier explains what problems he encountered in operating a battalion aid station when playing realistic casual- ty evacuation. Many of his vehicles were in the hands of others, and first aid was a problem. This is an eye-opener.

tle drills are the hallmark of a good unit. In "Team Battle Drills: Translating Doctrine Into Action," he shows us how to refine and hone responses to contact, indirect fire, and air attack. He also discusses the fine points of conducting a hasty attack, hasty defense, and hasty breach. Precious time is saved when a unit goes into its drill immediately, rather than waiting to think about what to do next.

Captain Ed Smith says that well-rehearsed bat-

One final word about something that is a little out of the realm of our usual subject matter, but is as equally important as anything else we do to keep our country strong. In November, we select our country's leadership at every level of govern- ment. We in uniform usually find ourselves among the ignored, but it doesn't have to be that way. Our Constitution makes us subordinate to our civilian leadership, but we are equal to any citizen when it is time to say who gets the jobs. Make your voice heard. Register and vote.

PJC

Mark Your Calendars: The 1989 Armor Conference will take place at Fort Knox, 8-12 May 1989.

~ ~~~~

By Order of the Secretary of the Army:

CARL E. VUONO

General, United States Army

Chief of Staff

Official:

R. L. DILWORTH

Brigadier General, United States Army

The Adiutant General

The Professional Development Bulletin of the Armor Branch PB 17-88-5 (Test)

Editor-in-Chief MAJOR PATRICK J. COONEY

Managing Editor JON T. CLEMENS

Commandant MG THOMAS H. TAlT

ARMOR (ISSN 0004-2420) is published bimonthly by the US. Army Armor Center, 4401 Vine Grove Road, Fort Knox, KY 40121.

Disclaimer: The information contained in ARMOR represents the professional opinions of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the official Army or TRADOC position, nor does it change or supersede any information presented in other official Army publications.

Official distribution is limited to one copy for each heavy brigade headquarters, armored cavalry regiment headquarters, armor battalion headquarters, armored cavalry squadron head- quarters, reconnaissance squadron head- quarters, armored cavalry troop, armor company, and motorized brigade headquarters of the United States Army. In addition, Army libraries, Army and DOD schools, HO DA and MACOM staff agencies with responsibility for armored, direct fire, ground combat systems, organizations, and the training of personnel for such organizations may request two copies by sending a military letter to the editor-inchief.

Authorized Content: ARMOR will print only those materials for which the U.S. Army Armor Center has proponency. That proponency includes: all armored, direct-fire ground combat systems that do not serve primarily as infantry carriers; all weapons used exclusively in these systems or by CMF 19-series enlisted soldiers; any miscellaneous items of equipment which armor and armored cavalry organizations use exclusively; training for all SC 12A. 128, and 12C officers and for all CMF-19series enlisted soldiers; and information concerning the training, logistics, history, and leadership of armor and armored cavalry units at the brigadelregiment level and below, to include Threat units at those levels.

Material may be reprinted. provided credit is given to ARMOR and to the author, except where copyright is indicated.

September-October 1988, Vol XCVII NOS

FEATURES

6 Armor in Low-Intensity Conflict: The Soviet Experience in Afghanistan by Major Michael R. Matheny

Translating Doctrine Into Action by Captain Ed Smith

18 Calibration Vs. Zeroing by Captain Mark T. Hefty

20 When Will We Ever Learn? by Captain Andrew F. DeMario

24 Human Factors Challenges in Armored Vehicle Design by Captain R. Mark Brown

26 Voices in the Sand: Deception Operations at the NTC by Captain George L. Reed

32 Armor Takes Cologne by Major John M. House

36 Medical Evacuation by CW3 William L. Tozier

39 The Search for Safer Combat Vehicles: How Close Are We Getting? by Donald R. Kennedy

42 Initial Training of Armor Crewmen by Captain Mike Benver

45 Support Platoon Operations in the Field: Class 111 by Captain Juan J. Hernandez

12 Team Battle Drills:

DEPARTMENTS 2 Letters 2 Points of Contact 4 Comnmander’s Hatch 5 Recognition Quiz 47 Professional Thoughts 48 Recognition Quiz Answers 50 The Bustle Rack 52 Books

~ ~~~

Second-class official mall postage paid at For( Knox. KY. and addHlonal mslllng flees. Postmaster: Send address changes to EdHor. ARMOR. A T W ATSB-MAG. Fort Knox. W 40121.

Distribution Rcslricllon: Approved for publlc release; dktribullon Is unllrnHed. USPS 467-970

Chinese Civil War Researcher

Dear Sir:

I am researching a military history of the Chinese Civil War 19451950 and am seek- ing information on the armored forces of the Republic of China. Can any of your readers help me with information on units and operations? 1 am also looking into the deliveries of armored fighting vehicles to China during the period 1943-1950.

Yours truly, E.R. Hooton, 24 Seacourt Road Langley, Slough, Berks, SL3 8EW, England

Longwinded Gunnery Techniques ... Shortsighted Solution

Dear Sir:

This is in answer to SSG lrvin "Red" Thomas' article in the MayJune 1988 issue of Armor. Before I reply to what I per- ceive to be his shortsighted article, please let me present some of my credentials to establish my credibility.

In my 25 years experience in Armor, 15 of which were spent as a tank com- mander in a line unit, either as a TC, sec- tion sergeant, platoon sergeant, or acting platoon leader, I am left wondering, is it

possible that the basic fire command is so esoteric in nature? So few seem to un- derstand what it is used for, or how to use it.

Why say Gunner," indeed? The standard fire command is nothing more than a pat- tern that is followed to bring fire on a tar- get. The beauty of this pattern is that it lends itself perfectly to what it is sup- posed to do, a succinct, effective way to control the firepower of your tank. Notice that I said firepower and not main gun. Firepower Is, in our case, plural, meaning more than one system. Page 6-2 of FM 17- 12-1 explains what the alert element is used for. "Gunner" is only one form of the alert. The same thing applies to the am-

(Note: Fort Knox AUTOVON prefix is 464. DIRECTORY - Points of Contact Commercial prefix is Area Code 502-624-x)o(x).

ARMOR Editorial Offices

Editor-in-Chief Major Patrick J. Cooney Managing Editor Jon T. Clemens Assistant Editor Robert E. Rogge Production Assistant Vivian Thompson Contributing Artist SFC Robert Torsrud

2249

2249

2610

2610

2610

MAILING ADDRESS: ARMOR, ATTN: ATSB- MAG, Fort Knox, KY 40121-5210.

ARTICLE SUBMISSIONS: To improve speed and accuracy in editing, manuscripts should be originals or clear copies, either typed or printed out in near-letter- quality printer mode. Stories can also be accepted on 5-1/4 floppy disks in Microsoft WORD, MultiMate, Wordperfect, Wordstar, or Xerox Writer (please in- clude a printout). Please tape captions to any illustra- tions submitted.

PAID SUBSCRIPTIONS: Report delivery problems or changes of address to Ms. Connie Bright, circula- tion manager, (502)942-8624.

MILITARY DISTRIBUTION Report delivery problems or changes of address to Ms. Vivian Thompson, AV 4h4-2610: commercial: (502)624-2610. Requests to be added to the free subscription list should be in the form of a letter to the Editor-in-Chief.

US. ARMY ARMOR SCHOOL

Commandant (ATZK-CG) MG Thomas H. Tait 2121 Assistant Commandant (ATSB-AC) BG Dennis V. Crumley 7555 Deputy Assistant Commandant (ATSB-DAC) COL Claude L. Clark 1050 Command Sergeant Major CSM John M. Stephens 4952 Maintenance Dept. (ATSB-MA) COL Garry P. Hixson 8346 Command and Staff Dept. (ATSB-CS) COL A. W. Kremer 5855 Weapons Dept. (ATSB-WP)

1055 Directorate of Training & Doctrine (ATSB-DOTD) COL Donald E. Appler 7250 Directorate of Combat Developments (ATSB-CD) COL Donald L. Smart 5050 Dir. of Eval. & Standardization (ATSB-DOES)

LTC(P) George R. Wallace 111

Mr. Clayton E. Shannon 3446 Training Group ( ATZK-TC-TB F) LTC William C. Malkemes 3955 NCO Academy/Drill Sergeant School (ATNCG) CSM Johnny M. Langford 5150 Director, Reserve Component Spt (ATZK-DRC) COL James E. Dierickx 1351

LTC Albert F. Celani 7809

COL Garrett E. Duncan 7850 TRADOC Sys Mgr for Tank Systems (ATSB-TSMT)

Office of the Chief of Armor (ATZK-AR)

(ATZK-AE) Army Armor & Engineer Board

COL Eugene D. Colgan 7955

2 ARMOR - September-October 7 988

munition or weapon element. (On other tanks in the inventory, this can also in- clude a sight or light that the TC wants used). Many times, the tank commander will be presented with a choice: for ex- ample: Your M1 tank comes upon 20 to 30 enemy troops standing around two trucks at a range of 1,OOO meters. Using your sample fire command, you tell your gunner, "TROOPS," and lay the gun. The gunner wlll say "OK ... But what do you want me to shoot them with?" It is the tank commander's ]ob to determine how he will engage a target, before the engagement begins. Do you get the idea? Your way, when used outside a range en- vironment, could cause some confusion. On the other hand, the standard fire com- mand format will lend itself to any situa- tion or weapon system. The standard fire command format lets you, the TC, effec- tively control the firing of your tank. It may help you better understand what is hap- pening if you think about it this way. The gunner handles the gunning, the com- mander handles the commanding. The fire command, used by a section leader, controls the fires of the section and by a platoon leader, the fires of a platoon.

ARMOR - September-October 1988 3 L

In all cases, the pattern is the same. Believe it or not, it will even help you as- similate a new member into your crew. Even scouts and replacements from other tank systems are familiar with the events that happen during an engagement. With about five minutes training, I can have an M48 tank gunner functioning on an M1, if I have to. This stuff works. If It ain't broke, don't fix it. Time for a war story to il- lustrate a point.

When I was a young buck sergeant, I had an excellent gunner who happened to be a Cajun. Now, none of us were ever sure of what this boy was talking about. Oh sure, he spoke English, but in a way that I, and the rest of the crew, had never heard, We were on Range 45 at Graf, I think. I remember It was a night range and the tank was an M60A1. We were just starting our run and had pulled into the first firing position. 1 got illumination on the target and gave my fire command. Crew responses were perfect, and we sent one downrange. I was sensing over the top of the cupola and saw the round go right over the target. I gave a sub- sequent fire command of "OVER, DROP ONE," and my gunner responded with "FIRE." Now, I was the tank commander and no one tells my crew to flre but me. I control the tank, no one else. I leaned back to scream at my gunner to get his act together and I saw him leaning back in his seat, looking up at me, and again he said, "FIRE." It was then that I saw that

the whole inside of my turret was lit up and my tank was actually ON FIRE!

The point here Is, be very selective in what you are going to have your crew respond with in your fire command. Do you really want him to say FIRE or FIRING or FIRED when you are the tank com- mander. A a tank commander, you don't want any surprises during an engage- ment. Start a fire command some day and hear an "Oh, Shit!" right in the middle of it. See what that does to your con- centration. SSG Thomas said, "Battlesight gunnery is an idea whose time has come and gone." Come on, Sarge, wake up. Bat- tlesight gunnery works. And this is just what you are talking about, speeding up the firing sequence.

Battlesight gunnery techniques and reduced fire commands (pg 6-10 of FM 17-12-1) let you do just that. The problem with battlesight is that most tankers don't understand what it is, or how and why it works.

Change 2 to FM 17-12-1 (though not per- fect) will help to clear this up when it is published. I hope. As for the subsequent fire commands, again, these are control measures for the TC and should not be changed. Subsequent fire commands are not at all complicated. They are nothing more than an adjustment to allow you to hit a target. You tell us to do away with them, then you use them in your samples. I think subconsciously you know there is a need for them.

1 saved this next topic for last because It is a particular irritant to me. You state that changing ammo in the middle of a fire command is not a big problem, but the way we do it is. A good commander knows the limitations of his equipment, as well as the capabilities. You then go on to say the UCOFT is programmed for U.S. doctrine. Who said so? I have spent some time in the UCOFT and went through an I/O course. What I got out of the training was a very good understanding of what the COFT is, and how it works.

I needed this in my work to enable me to talk intelligently with the personnel at the COFT center about their training development, prob-lems, and needs. The other thing I got from my COFT training was physically ill. My blood pressure be- came so high because of the exaspera- tion I felt at the programs in the com- puters that I did, in fact, become ill. You are absolutely right when you say , "Remember, you do in battle what you do in training." That is what is wrong with the COFT. In order to progress through the

matrix, you have to learn and practice COFT standards. In other words, play the machine. If someone is certified In COFT, that shows me one thing - that he is cer- tified in COFT. He can play the machine. Until a few things are fixed, 1 will never cer- tify because I refuse to practice bad habits when it comes to tanking. If you want to fix something, then COFT is a great place to start. It needs it.

MG Thomas H. Tait has an article in the same issue of ARMOR where he discus- ses using rehearsals in training. Read it; the general has it right. He calls It rehears- als: I still call It drill, but it is the same thing. The same principle applies to using a fire command, too. Get the crews to learn the fire command sequence right the first time. Then practice, practice, prac- tice. Drill the mind and the body until you do it without thinking.

I always taught my crews the equipment first, to include the sight reticles, then how to respond to my fire command, not one specific situation. And then I would teach them gunnery. I never trained for a range, only for different types of engagements. If I could see a target, my crew could kill it.

As a final thought, let me say that you are right, Sarge. Lase and Blaze works, and it works well. The M1 is a fabulous piece of equipment. Our boys proved that at CAT-07.

All the TC has to say Is TANK-FIRE, or COAX-TRUCK-FIRE. It works. But think of the support they had! Extended field use does cause problems. You have to be able to operate around those problems. The standard fire command, as is, lets you do that. It will help you in the long run.

Believe me, I know. I've been there.

L.E. WRIGHT Fort Knox, KY

More on Fire Commands

Dear Sir:

The article by SSG Thomas in the May- June issue of ARMOR Magazine brings up many interesting ideas concerning the cur- rent "Direct Fire" doctrine, specifically ele- ments of a precision initial and sub- sequent fire commands, the gunner's response to those commands, multiple tar-

Letters continue on Page 49

i

MG Thomas H. Tait

Commanding General

US. Army Armor Center So You Want To Command a Battalion ... When promotion or command

selection board results are an- nounced, the Armor Center Proponency Office, in concert with Armor Branch, immediately analyzes them. These results are use- ful to the branch and to the center when we advise officers about their possibilities for promotion, com- mand selection, and, in the case of lieutenants, retention.

The 1988 Battalion Command Selection Board results went through this rigorous process. The records of the 35 selectees were screened, and the results, to those of us who have been involved with boards for some time, were not surprising. In fact, they cor- roborated what we knew from past experience. For instance, ap- proximately one year ago we looked at the records of 104 serving bat- talion commanders and battalion command designees and found that 102 served as battalion S-3s or XOs and the other two served as brigade s-3s.

This is the 1988 Battalion Com- mand Selectee Profile:

0 The predominant year group was 1971, (57 percent), followed by 1972 (23 percent). Selections were also made from year groups '68, '70, and '73. It is evident that we are selecting younger officers for com- mand. Therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that the predominant year groups for next year's selectees (it will be a larger list) will be 1972 and 1973.

0 There were four Vietnam veterans selected - 11 percent. There are very few combat-ex- perienced officers in the queue for

battalion command. This is not ter- ribly important because we did a lot of dumb things in Vietnam, and many of the lessons learned simply do not apply to today's high speed, high technology, heavy combat.

0There were a number of repeti- tive company commanders, and the length of time spent in command was interesting. The average time in first command was 18 months. The number selected for second com- mand was 13 (37 percent); and the average time in second command was 18 months. Four were selected for third command (11 percent). The average time in third command was 24 months.

0All had served or were serving as a battaliodsquadron S3 or XO. The average time in eithcr position was 15 months.

0 A smaller number served as brigadehegiment S3s or XOs (14 percent and 17 percent, respective- ly).

0All were CSrGSC graduates (a requirement for promotion to LTC - nothing surprising here).

0 Interestingly, 87 percent of those selected had a master's de- gree or better. However, the board did not consider this a discriminator.

001 the 35 selected, eight had either Joint Professional Military Education (JPME) or had served in a joint assignment.

There are certain truths: one must command well in order to be promoted to major and subsequent selection for battalion command.

The number of companies com- manded is probably not a dis- criminator; however, if you are a su- perior company commander, you may very well be selected to com- mand the headquarters element of your battaliodsquadron or brigade. The real discriminator is serving as a battalion S3 or XO. It is readily evident in Armor that if you haven't done so, your chances for battalion command selection are poor at best.

The next question is how do 1 get to serve in a battalion as a major? First, ensure that Armor Branch knows your desires. Then, if as- signed to USAREUR or a large in- stallation like Fort Hood, it is up to you to make every effort to get to a battalion. As a personal experience, when commanding the 1st Indepen- dent Cavalry Brigade of the 8th Im- perial Division in Mannheim (1979- 1981) I had difficulty getting Armor majors into the tank battalions and the cavalry squadron. There were plenty of them in Heidelberg, but they were too comfortable or too im- portant. My advice is to seek the troop assignments if you want to be a warrior leader. We have all kinds of opportunities to track in alter- nate specialties. We need warriors in a command track - our soldiers deserve that.

After all, warfiglltriiig is riot an amateur sport!!

Treat 'Em Rough!

(CPT Fierko, Ofice of the Chief of Annor, provided statistics.)

4 ARMOR - September-October 7 988 I

Armor in Low-Intensity Conflict (LIC):

The Soviet Experience

In Afghanistan

(Part II of two parts)

by Major Michael R. Matheny

Although armor was born on the high intensity battlefield, both super- powers have employed mechanized forces in low intensity conflict. At lirst, the U.S. Army expected no role for armor in Vietnam, but the employment of mechanized forces grew steadily throughout the con- flict (see July-August 1988 ARMOR). In contrast, the Soviets overrated the role of armor in Af- ghanistan.

Prior to the Soviet invasion of Af- ghanistan, in a number of articles which discussed mountain warfare, several military authors writing in Voenrtvi Vestrtik confidently asserted that tanks could operate "jointly with motorized rifle and artillery units, and even sometimes inde- pendently."' By 1982, after three years of fighting, articles discussing armor operations in mountainous terrain were much more cautious.? In the same year, the popular press in the West claimed that the Soviets had chan ed their tactics in Af- ghanistan. F

In both Vietnam and Afghanistan, the success of armor depended upon the function it fulfilled within the combined arms team. J.F.C. Fuller defined these functions as finding, holding, hitting, protecting,

and smashing. In a previous article, 1 examined the role of armor in Vietnam using these functions to analyze the doctrine for armor in LIC. Now, I propose to do the same for the Soviet employment of armor in Afghanistan and then suggest the implications for armor doctrine in LIC.

The first Soviet postwar (WWII) experience in low intensity conflict began on 24 December 1979 when the Rcd Army invaded Afghanistan. In a well-planned operation, an air- borne division seized the capital at Kabul, while two motorized rille divisions attacked from across the Soviet border. The invasion force grew into the 40th Combined Arms Army, with seven motorized rille divisions and an airborne division, supported by five air assault brigades. The Soviet divisions came into Afghanistan with no specific doctrine for counterinsurgency. They came armed only with their su- perior technology and a convention- al doctrine to employ it.

Combat operations in Afghanistan essentially mean mountain warfare. The range of the Hindu Kush covers half the country, with peaks rising to 17,000 feet. Although the Soviets consider combat in moun-

tains as warfare under special condi- tions, they have no specific doctrine for fighting guerrillas in moun- tainous terrain. Apparently, they believe that tactics suitable for com- batting regular forces will work equally as well against guerrillas. The key elcments in their offensive doctrine for mountain warpare are their unshakeable faith in combined arms and the importance of mechanized forces.

Soviet doctrine forsees an impor- tant role for all the arms of service in mountain warfare. Recognizing the difficulty of massing artillery fires and "the limited accuracy of ar- tillery in the direct-fire role, tanks supplement the artillery and provide support by fire for maneuver forces."' The Soviets con- sider the BMP particularly suited for combat in mountainous areas be- cause its armor can protect the in- fantry squad while its armament can hit the enemy? With the exception of special operations forces, the en- tire Soviet army is mechanized. The very force structure of the Red Army suggests that primarily mechanized forces will fight moun- tain warfare. The doctrine does state that motorized rifle troops will dismount to attack, but they will at- tack with support from both tanks

6 ARMOR - September-October 7988

~

and BMPs. Airmobile infantry is also important and can secure high ground otherwise inaccessible to the motorized troops. All combined arms encircle and destroy the enemy in a coordinated attack.

infantry combat vehicles swept rapidly northward, ploughing through whatevcr was lcft of thc set- tlements."' The offensive drove many of the Afghans into exile, but failed to crush the resistance.

In a typical attack, helicopters con- duct reconnaissance ahead of the main body. On the ground, combat reconnaissance patrols scout ahead to identify less accessible routes for possible use by the outflanking detachment. The main body proceeds up the most accessible route. The next take the command- ing heights along the route of ad- vance or to the rear of the enemy at all costs. The outflanking detach- ment, which can be either motorized rifle units or airmobile troops, does this. The outflanking detachment would ideally contain artillery and engineers. Once the dominant heights are secure, a coor- dinated attack - preferably from two directions - completes the en- circlement and destruction of the enemy. 6

The functions of the various arms determine their employment. Helicopters and ground reconnais- sance units find; tanks and mechanized infantry protect, hit, and destroy; airmobile infantry also fm and destroy; finally, artillery, rotary, and futed-wing aircraft hit. Soviet officers probably had little idea how to adjust this tactical sys- tem in order to work in the low-in- tensity environment of Afghanistan.

Shortly after the invasion, the Soviets began large-scale offensives to pursue the Miijuliediri, the resis- tance forces, to their strongholds. In February 1980, 5,000 Soviet troops attacked into the Kunar Valley. For two days, the Soviets hammered the area with artillery and air strikes. Troops then airlanded onto the nearby ridges. Following the air as- sault, "columns of tanks and BMP

A year later, the Soviets were un- able to do any better. Some Western observers claimed the "Soviets' tactical reliance on armor curtailed their effectiveness in deal- ing with the guerrillas."* At least one analyst pointed simply to the Soviet inability to execute their own doctrine. The motorized rifle divisions that took part in the in- vasion had at least 50 percent reser- vists on 90-day call-up. Training was certainly an important factor. A year after the invasion, however, an eyewitness account of a battle that took place at Paghman, 15 miles northwest of Kabul, offers some in- sights. In the three-day battle, the tanks and BMPs made headway over the hilly terrain. However, only a few reluclzant Afghan infantry units (forces of the Soviet-backed regime) supported the armor. The Afghan infantry failed to close with the enemy. The Mujahcdirt roamed the battlefield in small groups, armed with RPG-7s and antitank grenades. Despite their advance, by the third day, the Soviets were forced to withdraw their armor? Obviously, when the infantry failed to fulfill its function, the combined arms team was broken.

The reluctance of the Afghan units to attack their countrymen was un- derstandable. Within a year of the invasion, the Afghan army disin- tegrated, from a force of 90,oOO men in 1979 to 30,000 in 1981. The Soviets looked for solutions by in- creasing their troop strength and ad- justing their tactical system. Less willing to depend on their allies, the Soviets annually increased their troop strength by 10,ooO in 1981, 1982, and 1984. Soon these Soviet

troops were taking the field and as- suming more of the combat burden. The Sovicts also hegan what one oh- server called, "a trial-and-error searcv for tactical solutions."

By 1982, the Soviets continued large-scale offensives, but with some new tactical adjustments, principally with a marked increase in the use of airmobile and special operations for- ces. In May and June, the Soviets and their Afghan allies massed 15,000 troops against 3,500 Mujuliediri in the Panjshir Valley, 40 miles north of Kabul. The Soviets at- tacked into a 300-meter to two- kilometer-width gorge. Air assaults descended on the ridges, while an armored column attacked up the val- ley. The air assaults ran into stiff resistance and had to withdraw. Without command of the dominat- ing heights, the Soviets took heavy losses. After a good deal of fighting, the Soviets declared victory and returned to their permanent gar- risons. The Miijaltediri returned also, which prompted another Soviet offensive into the Panjshir later the same year.

On better ground, the Soviet mechanized forces found it much easier to encircle and thus obtain better results. The city of Herat sits at the western foot of the Hindu Kush near the desert. It had long been a hotbed of resistance. Follow- ing the Panjshir operation, the Soviets surrounded Herat with more than 300 armored vehicles and conducted a house-to-house search. Most of the Mirjulrediri had fled, so the Soviets met little resis- tance." All the same, the Soviets reestablished their control of the city.

The most effective tactical adjust- ment made by the Soviets was the in- creased use of special forces (Spetsrtai and airborne units) in small-scale search-and-destroy mis-

ARMOR - September-October 7 988 7

sions. Curiously, even these opera- tions occasionally involved armor. A British journalist traveling in Af- ghanistan reported a mechanized ambush. Six BMDs were airlifted into a Mtijaltedirt infiltration route along the Pakistan border just before dark. In a 10-day period, the small armored force destroyed six insurgent sup ly groups and killed 18 Mtijalreciiu. P2

Most heliborne operations were still in support of large-scale offen- sives, which depended mainly on mechanized forces in the combined arms team. The Kunar Offensive, which took place in May 1985, is a good example of the evolution of

the Soviet tactical doctrine and its effectiveness. The primary objective of the Kunar operation was to open the Jalalabad-Chagha Sarai road and establish security posts to block Mtljahediri infiltration routes into Pakistan. The operations also had the subsequent mission to destroy insurgent strongholds in Pesh Dara and Asmar. Finally, the Soviets in- tended to relieve the garrison at Barikot, which had been besieged by the Miijaltedin for over a year. To accomplish these goals, the Soviets gathered two Afghan in- fantry regiments, two Afghan com- mando units, a border brigade (all Afghan units were at 50-percent strength), a Soviet motorized rifle

-

"Soviet success, how- ever, was only temporary- Once the Soviet troops returned to their per- manent bases, the Mujahedin eliminated the isolated securitv posts ...I'

regiment, and a Spetsrraz battalion. On 23 May, the Soviets led the way from Jazlalabad to Changa Sarai.

After establishing security posts along the highway and a strong firebase at Changha Sarai, the Soviets launched attacks on two axes, with a supporting attack toward Pesh Dara. An air assault, planned to assist the advance, be- came isolated when the pound at- tack stalled. The air assault force suffered heavy casualties and had to withdraw by helicopter. The main at- tack to Asmar was also supported by Spetsria: commando teams, which seized key points along the route. The Spefsrra: teams leap- frogged ahead of the main body during the day, but withdrew at night. Fierce battles broke out near Narai, but with the help of 150 helicopter gunship and aircraft sor- ties a day, the Soviets pressed on toward Barikot. As the main column approached Barikot, the Soviets airlifted a strong striking detachment into the garrison. They then launched a pincer attack simul- taneously from the garrison and the relieving column. In the face of such pressure, the Miijahedirr withdrew into the rnountains.13

Soviet success, however, was only temporary. Once the Soviet troops returned to their permanent bases, the Mtijaltedin eliminated the iso- lated security posts and once again besieged Barikot.

In 1985, Soviet offensive tactical doctrine still called for mechanized forces to protect, hit, rk, and destroy the enemy.14 In practice,

8 ARMOR - September-October 7988

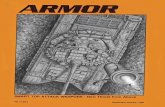

Soviet experience in Afghanistan parallelled the U.S. Vietnam campaigns against similar indigenous guerrillas.

The Soviets discovered that while they might win set-piece battles, it was difficult to find and fix the Mujahedin. And even if they gained control of an area, they had to remain there if they wanted to keep it.

I

... An uphill fight In Afghanistan, the Soviets quickly learned that they

could not maneuver along valley floors unless they controlled the heights along the route. These photos are from Soviet publications.

I 9 ARMOR - September-October 7988

special heliborne forces most often compromised the outflanking detachments to Ti the enemy. As is evident in the Kunar operation and others, the mechanized forces could hit and protect, but rarely could they fuc or destroy with significant results. The Soviet doctrine remains basically the same; seize the heights, then encircle and destroy with a coordinated combined arms attack. The Soviet mechanized forces were unable to fulfill their prescribed functions, and so their role in the combined arms team changed. Mechanized forces continued to be the primary instrument in large- scale offensives to protect Soviet troops while hitting the enemy. Spe- cial heliborne forces fvc and in small- scale operations find, fur, and destroy. Other adjustments to the of- fensive tactical doctrine have in- cluded saturation bombing from high-altitude bombers, and chemical weapons.

The failure of Soviet mechanized forces to perform as prescribed is probably due to terrain, organiza- tion, and the influence of their operational plan for victory. Years ago, J.F.C. Fuller granted that truly steep terrain was unsuitable for mechanized forces. Instead, he em- phasized their utility in securing the valley Obviously, there are places where tracked vehicles simp- ly cannot go. When the Mtijaltediii withdrew into the mountains, often they could be pursued only by foot and fire. A doctrine that called for outflanking detachments composed of mechanized forces and other combined arms elements, such as engineers and artillery, was bound to undergo some adjustments.

The organization of the Soviet Army, most of which is mechanized, encouraged the Soviets to try the same old hammer and anvil tactics. Their insistence on combined arms is certainly correct in the right

place, but operations in difficult ter- rain - mountain or jungle - call for a high order of cooperation. In many of their operations, they ap- peared unable to execute their doctrine or the adjustments they made due to poor synchronization of the combined arms. Isolated air assaults, failure of the infantry to close with the enemy, failure of the combined arms to fulfill all the tacti- cal functions required to destroy the insurgents, were all key problems. Some readers may point to poor training or reluctant allies, but part of the reason may lie in tactical or- ganization. If the U.S. Army was any better using mechanized forces in Vietnam, it may have been due to the concept and organization of ar- mored cavalry. Although the Red Army has reconnaissance units, it has no comparable organization for an organic combined arms force. The American ACR is a balanced force, combining all the arms in a tightly-knit unit, which constantly trains as a team.

Finally, to a much greater degree than was the case in Vietnam, the Soviet operational plan influenced tactics. Apparently, the Soviets in- tended to defeat the insurgency at an operational, rather than tactical, level. They used military force not so much to destroy the insurgents, but to exhaust and attrit them. The Red Army protected the urban areas and lines of communication, patiently waiting for the insurgency to collapse, or for Sovietization to remold the country. In order to min- imize political and military costs, they maintained a relatively small force to deal with an insurgency in a large country. In short, the Soviet doctrine for mechanized forces in Afghanistan did not work to crush the resistance because the number of troops was insufficient. The Soviets, "in contrast to American policy in Vietnam, would apparently rather risk losing tactically than

spending more on their purely military adventures.""

Whether in Afghanistan or Viet- nam, history demonstrates that armor does have a role in LIC. The most appropriate tactical doctrine for mechanized forces in LIC depends upon the combat function they will serve within the combined arms team. As noted, these func- tions will vary with terrain and the operational plan. At the very least, armor has demonstrated that in the LIC environment it can protect and hit. When properly organized and employed, it may also be used to find, fur, and - in conjunction with the other arms - destroy insurgent forces. To make the most of armor on the LIC battlefield, an army must have a good combined arms doctrine before it is committed to fight. The evidence suggests that mechanized forces are best employed in battalion- to brigdde- size small-scale cordon search operations. Their mobility and firepower are best employed in en- circlement operations, or as a reac- tion force, or reserve.

Keeping Fuller's battlefield func- tions in mind, the implications for armor in LIC may look like this:

Protect: In the near term, opera- tions require a light armor vehicle of 15-20 tons to meet deployability requirements. Strap-on armor might be an alternative once the vehicle deploys to the contingency area." If money is not available for research and development of a new vehicle, modified M2s or M3s would be preferable to less effective alter- nates, such as the HMMWV or a product-improved M551. In fact, weight of the vehicle is less a deployability problem for LIC than other lcvels of war. Light forces can initially secure the endangered government until the heavier and better protected armored vehicles

10 ARMOR - September-October 7988

arrive. Although a light tank may be the optimum solution, we should not hesitate to deploy M60 or M1- series tanks with follow-on contin- gency forces involved in LIC.

In the future, the next generation of armored vehicles should have a common system base. If weight could be reduced to the 35- to 40- ton range, similar to the current family of Soviet tanks, deployability of main battle tanks would greatly improve. In this case, a standard or- ganization for armor units would be- come possible, perhaps eliminating the need for light armor units. Since deployability drives armor to reduce weight and thus reduce protection, research and development should focus on improving the means of transporting heavier vehicles and developing lighter armor.

Hit: In the near term, lire systems that suppress, such as the 25-mm automatic cannon and the grenade launcher, should be most effective in permitting forces to close with the enemy. Large-caliber direct-lire weapons, such as the 105-mm tank cannon, remain effective against in- surgent fortifications and point tar- gets.

In the future, a ma.jor concern in LIC is to limit the destruction caused by military operations. We should push technology to develop acquisition systems that permit the delivery of direct and indirect "smart" munitions. Discreet fires would limit collateral damage.

Find: Local and battlefield intel- ligence play a large role in locating the enemy. The combined arms or- ganization on the LIC battlefield should have an attached or organic military intelligence company. Or- ganic aerial reconnaissance assets would also increase effectiveness. Fix: In the near term, using air-

mobile and ground forces to f i i the

enemy through encirclement will continue to be the most viable method. Whether airmobile infantry or fast-moving mechanized troops do this will depend upon the terrain and the urgency of the situation.

In the future, technology and doctrine should look at the develop- ment of armor vehicles that a helicopter can deploy to the bat- tlefield. In appropriate terrain, this would give the fixing force the ad- vantages of protection, firepower, and mobility after commitment. We may also wish to consider the poten-, tial of a non-lethal incapacitating gas. Once such a chemical weapon is delivered into a suspected insur- gent area, protected troops could quickly move in to search and sort out insurgents from civilians without loss of life.

Destroy. Combined arms will remain the most successful way to conduct offensive operations in LIC. A single combined arms doctrine, which prescribes the tacti- cal employment of all arms, to in- clude the armored cavalry, will con- tribute strongly to our chances of success in the most frequent level of war -low intensity conflict.

Notes

Larry A. Briskey, Soviet Ground Forces in Afahanistan: Tactics and Performance. unpublished graduate paper, Georgetown University, 1983, p. 5.

1.

21bid, p. 6. 3. Aernout Van Lynden, "Soviets Change

Tactics Against Afghan Rebels," Washinaton Post, 27 Dec 1982, p. A-26.

General Lieutenant D. Shrudnev, Vovennvi Vestnik, July 1978, quoted in Briskey, Soviet Ground Forces, p. 17. 5C. N. Donnelly, "Soviet Mountain War-

fare Operations," International Defense Review, June 1980, p. 829.

4.

ARMOR - September-October 7988

" Ibid, p. 831. 7. Edward Giradet, Afahanistan. The

Soviet War, St. Martin's Press, NY, 1985,

8Van Lynden, "Soviets Change Tactics,"

'Ibid. 10'Zalmay Khalilzad, "Moscow's Afghan

War," Problems of Communism, Jan-Feb 1986, p. 4.

"Charles Doe, "Soviets See Time on Their Side in Afghanistan," Army Times, 21 Jan 1985, p. 28.

12'David Isby, The Better Hammer, Soviet SDecial Operations Forces and Tac- tics in Afahanistan. 1979-1986, un- published paper, 1986, pp. 26- 27.255P255D

13'This account is taken from COL Ali Jalali, The Soviet Militarv Operation in Af- ghanistan and the Role of Liaht and Heavv Forces at Tactical and ODerational Level. Light Infantry Conference, Seattle,

14'F0r a discussion of Soviet offensive tactical doctrine see COL G. banov, "Bat- tle in a Canyon," Krasnava Zvezda, 1 Oct 1985, translated by JPRS-UMA-85068.

15'J.F.C. Fuller, Armoured Warfare, Greenwood Press, Westport, CT, 1983. Originally published in 1931 as Lectures on FSR 111, p. 168.

l6'COL Jalali, Soviet Owrations, p. 163. "*Directorate of Combat Development,

Armor Support of Liaht Forces, transcript of concept briefing, 17 Jan 1984.

p. 33.

p. A-26.

WA, 1985, pp. 178-179.

Major Michael R. Matheny taught history at the Armor Ad- vanced Course at Fort Knox, KY, and at the USMA at West Point, NY. He is a graduate of the CGSC and the School of Advanced Military Studies. He commanded a tank company and served as a tank battalion S3 with the 3d Infantry Division in Germany. He is cur- rently assigned to the G3 Plans section of the 1st Caval- ry Division, Ft. Hood, TX.

71

Team Battle Drills: Actions On Contact

Translating Doctrine into Action

by Captain Ed Smith

Well-rehearsed battle drills are the hallmark of a good unit. Most units understand and can quickly prioritize individual training, but the number of collective tasks that a company/team must be able to ex- ecute often overwhelms them. Bat- tle drills are the key building hlocks for performing more complex tasks, such as a night attack against a strongpoint, and also provide a framework for training specific skills, such as scanning and target acquisition. In addition, they ease the rapid assimilation of new units and new soldiers. Battle drills enable the small unit leader to trans- late doctrine into specific actions on the battlefield.

Examples of the following seven battle drills for offensive operation- sare:

0 Actions on Contact 0 Hasty Attack 0 Hasty Breach 0 Movement Formations 0 Hasty Defense 0 Reaction to Indirect Fire 0 Reaction to Air Attack

Although not all-inclusive, these battle drills generally address the most frequent small unit engage- ments that will occur during offen- sive operations. They are in order of importance, and cover those engagements where we stand the greatest chance of killing the enemy or of suffering the greatest number of casualties. These drills are not a substitute for the detailed planning so necessary for a deliberate attack, but rather serve as a quick reaction to the unexpected. Record the bat- tle drills in the unit’s tactical SOP, and be as specific as possible at the squad and tank level. The use of matrices to detail individual squad and crew membcr actions for each drill is a good way to spell out ex- pected standards.

In garrison, practice the drills dis- mounted on a weekly basis and rein- force with mounted drills when resources permit. The drills in this article are for a tank-heavy team (Ml-M113 mix) with Stinger (V4- ton mounted) and attached FIST.

Our doctrine states that, upon con- tact, the team returns fire, seeks covcr and concealment, reports and then develops the situation. However, doctrinal publications fail to emphasize that the primary reason for actions on contact is to survive long enough to destroy the enemy by some other maneuver. The team’s only recourse may he an immediate assault of the enemy force, but survival remains the un- derlying purpose. The commander translates these general require- ments into specific actions. The reaction must be violent and it must be automatic. Unfortunately, most units do not develop violent battle drills for actions on contact. The typical unit makes contact with the enemy, stops, and dies. It does not return fire because it doesn’t see the enemy. It doesn’t move to cover and concealment because there isn‘t any. It often dies before it can report.

Actions on contact are easier to understand if we think of the enemy fire sack as either a near or a far ambush. Far ambushes are much more common, because the enemy retains his standoff distance to shoot at us longer with his direct

12 ARMOR - September-October 7988

and indirect fires. In a well- designed fire sack, the nearest thing to a covered and concealed position can only be found by moving out of the enemy's fire sack or by seizing the enemy positions. In the far am- bush, backing out of this fire sack of- fers the shortest path to a "position" not covered by direct fire. Moving 500 meters to the rear temporarily pulls our chestnuts out of the fire and enables the command to survive the initial contact with maximum for- ces intact. However, if the enemy positions are closer than the nearest "position" outside the fire sack, the tcam faces a near ambush. In this in- stance, the lead platoon assaults the enemy position with all weapons firing in the direction of contact. Of the two types of ambushes, the near ambush is the most dangerous. For- tunately, it is the least likely of the two, due to its high risk for the enemy (exposed flanks and rear) and the limited availability of natural reverse slope positions in most terrain. As a result, the team's initial actions on contact are always for a far ambush. In both cases, the team fires rapidly, regardless of whether it has a target in its sights or not. During the operations order sequence, the Commander must template at what point along the unit's axis of advance he anticipates a near ambush (defiles, built-up areas, and woodlines) and where he expects a far ambush.

Anyone may initiate the actions on conlact drill. All crews immediately rcturn fire in their assigned orienta- tion, or at identified targets. Simul- taneously, the drivers put the vehicles into reverse (unless they can see a covered and concealed position within 100 meters), activate the on-board smoke system, and back up 500 meters. The designated crewman (it doesn't have to be the vehicle commander) gives a brief alert over the radio, per unit SOP.

Most units don't return fire because they do not see a target and they cannot find enough dead space to obtain cover and concealment. One quick radio transmission, by any crewman: "CONTACT FRONT (or LEFT, RIGHT, REAR)," weapons firing, and the lead platoon moving to the rear at high speed in a cloud of smoke will let everyone know that the team has made contact, that it's a far ambush, and the general direction. The lead platoon and the ovenvatching platoon are now moving back out of immediate danger, and the commander can enjoy a brief respite while he ob- tains more information and decides upon his options (hasty attack, hasty defense, bypass, or continue to develop the situation). The FIST re- quests fires, the executive officer reports to task force, and the platoon leaders look for favorable indirect routes to assault the flanks of the enemy position.

Only a platoon leader or the team Commander initiates the actions-on- contact drill. He announces "AC- TlON FRONT (or LEIT, RIGHT, REAR)." He then leads the platoon into an immediate assault of the enemy position.

All tanks guide on him in a wedge and place all fires at either iden- tified targets or likely enemy loca- tions. The crews do not activate on- board smoke systems and do not stop until the platoon leader issues further instructions.

In both versions of this battle drill, the overwatching platoon leader gives an immediate support by fire command to his platoon. Target priorities, in order, are: observed enemy positions, lead platoon's tracers, and likely enemy positions.

The overwatching platoon leader places the highest possible volume

I the commander must template at what point along the unit's axis of advance he an- ticipates a near am- bush (defiles, built-up areas, and woodlines) and where he exDects

moves as necessary to prevent the lead platoon from masking his fires and to see his target area.

Hasty Attack

After the initial actions on contact, thc commander analyzes his options and determines, based on his under- standing ol the mission and his war- gaming, that a hasty attack is the ap- propriate option. By definition, the sequence of events for any attack in- volves the troop-leading steps and the concomitant decision-making process. However, since companies hcquently conduct hasty attacks, a drill-like series of steps will increase the unit's chances of success.

The commander delays the assault to ensure the positioning and availability of dismounted infantry, indirect fires, and the support-by- fire etement. The hasty attack battle drill uses the lead tank platoon as the support-by-fire element and the other tank platoon, followed by the mounted infantry platoon, as the as- sault element.

First, the commander queries the FIST to determine if he can sup- press the position the commander wants to assault, isolate mutually supporting positions (real or templated), and screen the move- ment of the assaulting platoons. Next, the commander places the

I ARMOR - September-October 1988 l3 I

support-hy-fire element in the most advantageous position not masked by the assault. The commander will also cast about for other elements in the task force that may be avail- able for supporting fires. In a mechanized task force, the antitank company/team will be the most responsive and the task force com- mander usually places it in a sup- port-by-fire role. Don't overlook the availability of a supporting Vulcan unit. Finally, the commander refines the exact route for the assaulting platoons. The route crosses as little of the fire sack as possible and seeks the likely flank of the nearest enemy platoon position. The com- mander's frag order to the key leaders includes control measures

"Don 't overlook the availability of a supporting Vulcan unit.. . "

that are easily identifiable on the ground and a tentative dismount point for the infantry platoon. The commander strives for a large volume of indirect and direct fire to achieve fire superiority. If indirect fires are not available, the attack will rapidly become a multiple-arms fight instead of a combined-arms fight. The absence of indirect fire support will reduce the chances of success and will require very respon- sive supporting fires.

justs the rate of fire. The FIST at- tacks the team objective with artil- lery before the team reaches the fire sack, and uses mortars for assault- ing fires. He continually adjusts the mortar fircs to move 600 metcrs in front of the lead platoon. Six hundred meters from the first enemy position, the lead platoon leader calls for the artillery to lift and to shift to the closest mutually- supporting platoon.

Before the assault force begins to move, the commander issues a sup- port-by-fire command to the sup- porting tank platoon, and adjusts in- direct fire. For example, the com- mand, "Sierra 11, support-by-fire, 2 and 3, checkpoint A12," orders the platoon to support-by-fire with two rounds main gun per tank and three bursts of automatic fire per tank, per minute at checkpoint A12. However, if the tank platoon sees another target, it may engage it with the most appropriate weapon. The tank platoon leader confirms the tar- get by using a white phosphorus round or any type of tracer ammuni- tion that will reach the target reference point. The commander ad- justs this as necessary. The assault- ing platoon leaders will be keenly in- terested in this process. The sup- porting platoon commences firing and continues to fire until the as- sault element masks its fire. The platoon leader continues to reposi- tion his platoon to support the as- sault. The support-by-fire platoon sergeant reports ammo levels, by 10 percent increments, over the com- pany net. At a predetermined ammo level - for example, 40 per- cent - the platoon leader questions the commander about continued ammo expenditure rates. At this point, the first sergeant begins emer- gency Class V resupply for that platoon, and the commander ad-

The assaulting tank platoon leads, firing coax at all likely positions. The platoon leader reserves main gun fire for actual infantry positions and likely armor vehicle fighting positions. The infantry platoon moves mounted until the tank platoon encounters a position that it cannot destroy, or reaches terrain it cannot traverse. The infantry platoon then dismounts and assaults.

To distinguish between enemy and friendly infantry at distances over several hundred meters is difficult. Consequently, the commander must continue to designate control measures (no fire areas, engage- mcnt areas, and target reference points) in order to shift fires away from friendly forces as they advance.

Once the infantry dismounts, he may order support elements to cease engaging all infantrymen, un- less attacked or requested by the in- fantry platoon leader for a specific area. The dismounted infantry lcadcrs mark their positions. The in- fantry can use colored smoke, aircraft recognition panels, tracer fire, and relationships to terrain.

The infantry platoon destroys enemy infantry and pressures enemy armored vehicles to displace. The enemy vehicles now have a choice to either stay to die from a Dragon round, or to withdraw. The enemy

14 ARMOR - September-October 1988

"Infantry fighting vehicles lack the necessary firepower and protection to survive the initial actions on contact and to rapidly kill all types of enemy armor. Therefore, tanks should lead un- less the commander's need for security requires the use of dismounted infantry. It

vehicles will probably displace. During the time the enemy vehicles are moving they are most vulnerable to the supporting tank's fire, This "bird dog and shotgun" routine enables the infantry to flush the enemy and the tanks to kill them. Although the infantry will be doing most of the work, the tank cannon will kill the bulk of the enemy armor.

The commander now designates control measures for consolidating the enemy position. The designated target reference points identify mutually-supporting enemy posi- tions on the flanks, likely counterat- tack routes, and the most likely route for continued team move- ment. The executive officer an- nounces the location for the com- pany combat trains and decides whether he will require the platoons to evacuate casualties to the com- pany combat trains or if he will "tail- gate" the trains to the line platoons. The first sergeant receives the per- sonnel and equipment status from each platoon sergeant in order to direct cross-levelling of people and equipment and request urgently needed items.

Hasty Breach

The lead platoon detects an obstacle and immediately begins contact drill actions. This drill as- sumes that the enemy will cover his obstacles with fire. The initial report describes enemy activity and the obstacle type.

The first vehicle turns left, the second vehicle turns right and both

reconnoiter the obstacle. The two crews seek the following informa- tion:

0 Feasibility of forcing the obstacle 0 Location of bypass, if any 0 Likely breach site (one with

0 Location for support-by-fire most dead space)

position

The remaining vehicles of the lead platoon also identify near-side security positions (support-by-fire positions). The FIST requests in- direct fires that will obscure enemy observation of the team's hasty breach and fires that will suppress known and likely enemy positions that can place direct fires onto the team. The closer he can place the smoke to the enemy, the better. The FIST avoids placing smoke on the team and on the obstacle. The in- fantry platoon leader moves for- ward, selects a place to dismount his far-side security force. This ele- ment, led by the platoon leader, clears a footpath, using wire cutters and grappling hooks. This force moves to those positions that can place direct fires on the obstacle. The far-side security force maneuvers with all of the platoon's Dragons.

The far-side security force places suppressive small arms fires and an- titank fires on those enemy forces that can disrupt the breaching and assault force's operations. The far- side security force communicates with the near-side security force in order to adjust the near-side security fires onto positions the tank

platoon may not have identified. As a result, the far-side security force may have to move as far as two kilometers in open terrain. Under no circumstances does the far-side security force breach a footpath and just flop down on the other side of the obstacle. The near-side security force can already cover that far. The remaining squad-sized force conducts a hasty breach using ex- plosives or grappling hooks to physi- cally move surface-laid mines. If the mines are buried, the breaching force must use mine detectors and probes to locate and destroy (or remove) the mines. The breaching force then marks the breach site using smoke, engineer tape along the boundaries of the lane, or aircraft recognition panels elevated on long pickets near the entrance of the lane. The assault platoon moves through the lane, proofing it, and continues the mission.

Movement Drills

Although there are a large number of possible formations, consider limiting the team to five basic forma- tions: column of platoon wedges, team diamond, staggered column, column, and the line formation. The keys to security during movement are good target acquisition skills, overwatch elements, platoon leaders alert to changing requirements for dispersion, and making contact with the smallest enemy force possible. Consequently, do not shortchange unit alertness for the sake of a tidy appearance. Infantry fighting vehicles lack the necessary firepower and protection to survive . 1

ARMOR - September-October 7988 15 I

the initial actions on contact and to rapidly kill all types of enemy armor. Therefore, tanks should lead, unless the commander's need for security requires the use of dis- mounted infantry.

The platoon wedge should rarely exceed 200 meters in width. The platoon is not the element we want to spread out. The commander should consider the diamond or column of platoon wedges when his estimate dictates greater dispersion. Except during a movement to con- tact, most company/team formations should not exceed 800 meters in width. Distances greater than 800 meters make it difficult to achieve mass, and strain the command and control lunctions. This becomes more obvious once the entire bat- talion or brigade is viewed, rather than the company in isolation. The company combat trains, executive officer's tank maintenance track (with the first sergeant onboard), medic track, and the recovery vehicle follow as a fourth platoon in a like formation equidistant from the other platoons. None of the for- mations include wheel vehicles; due to their vulnerability to small arms and indirect lire.

If speed is important, and forward units provide security, then the com- mander may elect to use the column or the staggered column. Periods of low visibility may also lorce the use of a column formation.

Finally, the line formation can quickly posture the team for a sup- port-by-fire mission or a hasty defense. The unit staggers the line formation to achieve some depth and flexibility.

Regardless of the type of fornia- tion, the lead platoon routinely dis- mounts crewmen before crossing danger areas. Each crewman dis-

mounts with essential equipment (weapon, binoculars, and protec- tive mask).

The commander gives specific respon- sibilities to the platoon for scanning; for ex- ample, "Lead platoon to the front, second platoon to the left, third platoon to the right, and keep the team aligned with Bravo Team. The combat trains will maintain air guard and alignment with Co C to our rear."

"Under no circumstances does the commander permit the Stinger crew to fight from the assigned wheel vehicle ... Since there is not enough room in a tank, the commander selects an infantry vehicle, the maintenance track, or the recovery vehicle, for in- side protection for the two-man Stinger team. 'I

Hasty Defense

Often, we use the hasty defense to assume a sup- port-by-fire role or a counterattack- by-fire mission, rather than for a defense. Calling the drill a hasty defense places attention on the necessity to mass fires on TRPs along avenues of approach. The commander's frag order addresses the threat size and direction, the avenues of approach designated by his control measures, the indirect targets with thcir trigger points, like- ly air approaches, and the surveil- lance responsibilities for each platoon.

Reaction To Indirect Fire

The comniandcr must cover the in- direct fire threat in his instructions. He should template the maximum engagement lines for artillery and mortar fires. The team needs a good idea of where to expect fires. the typical sheaf dimensions, and when vehicles must mask during the operation if attacked with indirect fires. The unit must move out of the impact area as quickly as possible

while maintaining command and control. When under indirect fire, the unit cannot accurately return fire and cannot observe. If the unit does not move, all it can do is rcmain suppressed and become casualties.

J f the team has not yet engaged, then it moves at an increased speed along the direction of march. If within range of direct fires, and not overwatching another element, it moves back 400 meters. If defend- ing, it moves to alternate positions. When supporting-by-fire, the team moves forward 400 meters and then moves back as soon as the fires lift. The support-by-firc unit's overrid- ing concern is its ability to continue to provide fires.

Reaction To Air Attack

Under no circumstances does the commandcr permit the Stinger crew to fight from the assigned wheel vehicle. The supply sergeant super- vises the movement of the Stinger

16 ARMOR - September-October 1988

1 wheeled vehicle to a more suitable area. Since there is not enough room in a tank, the commander selects an infantry vehicle, the main- tenance track, or the recovery vehicle for inside protection for the two-man Stinger team and its mis- siles. Place half of the missile load on another vehicle.

Passive: If not attacked, the air guard platoon announces, "Bandits, East. Freeze," and the team ini- mediately stops. The Stinger gunner dismounts and prepares to engage.

Active: When attacked, the unit returns fire and disperses. The air guard platoon announces, "Bandits, East. Fire." The air guard platoon acknowledges any early warnings relayed by stations monitoring other nets. Due to the rapid nature of air strikes, each shooter judges when he should fire. Massed fire com- mands, while desirable, are usually impractical. All weapon systems, ex- cept tank cannon, engage attacking futed-wing aircraft that close within one kilometer. Crews use tank can- non against rotary wing aircraft.

After each Stinger engagement, the gunner reports the number of missiles fired and the number remaining. At the 50-percent point, the first sergeant obtains emergency resupply of Stinger missiles. Each platoon leader reports the number of automatic weapon engagements from his platoon.

Conclusions

Based on experience at the NTC, battle drills do not lend themselves well to a defensive operation. The uniqueness of each avenue of ap- proach and thc resulting engage- ment areas, TRPs, siting of obstacles, and selection of fighting positions require original thought. Nor do battle drills appear to work

"Many units train- ing at the NTC do not sutvive the ini- tial actions on contact simply be- cause the team lacks a rehearsed battle drill. An appropriate

battle drill enables the unit to react quickly and de- vote attention to the unique as- pects of each combat situation. 'I

I I

well at the task force level for more than a movement to contact be- cause of the greater spectrum of op- tions and unccrtaintics present in larger formations. These battle drills do not cover every aspect of offensive operations. However, they do cover the most important actions a unit will encounter during most of- fensive operations. Commanders can use these drills as a starting point and modify them to fit their theater of operations and thcir unit's mission essential task list.

Many units training at the NTC do not survive the initial actions on con- tact simply because the team lacks a rehearsed battle drill. An ap- propriate battle drill enables the unit to react quickly and devote at- tention to the unique aspects of each combat situation.

ARMOR - September-October 1988

Captain Ed Smith was commissioned in Armor from West Point in 1977 and served as a com- pany commander with the 1-68 Armor in West Germany. He also served as high school ROTC liaison officer in the 1st ROTC Region. Since 1985, he has been assigned to the National Training Center, where he has taken part in more than 37 rotations. He is presently assigned as the NTC's mech- anized infantry task force battle staff analyst.

77

I Calibration Vs. Zeroina

E '1

by Captain Mark T. Hefty

The M60A3 main battle tank has a complex fire control system. The current method of calibrating the M60A3 is to conduct an accurate boresight, then fire a round at a 900- meter target panel. If the round hits the target, the tank then fires a con- firmation rQund at a 1,500-meter tar- get panel. If that round hits, then the tank is calibrated. If the first round hits and the second round misses, a third round is fired at a 1,250-meter panel. If that round hits, the tank is calibrated.

If the tank misses the first round at the 9O-meter panel, it is not calibrated, and the crew must check several items, such as boresight and knob settings on the gunner's con- trol unit (GCU). The GCU feeds data into the computer, including gun tube wear, air temperature, and elevation.

The crew follows the same proce- dures if it hits the 900-meter panel. but misses both the 1,500-meter and 1.250-meter panels.

Normally, the company master gunner is in the calibrating tank, and the battalion master gunner is in the range tower. They are check- ing the elevation output reading from the elevation actuating arm and comparing the reading to the solution in the ammunition tablcs, which gives a mathematically calcu- lated output reading and a small tolerance. If the tank's output read- ing is outside the given tolerance, the tank does not fire, and the tur- ret mechanics check the entire fire control system for malfunctions.

Inside the GCU are four very spe- cial jump knobs. Two of them con- trol azimuth and elevation for HEAT ammunition and two control azimuth and elevation for SABOT. The knobs allow manual input of correction data to the computer.

Currently, the only authorized knob adjustment is a -.8 mil eleva- tion for HEAT ammunition. That number is derived from historical data indicating that HEAT consis- tently shot high.

After a particularly disappointing Level I gunnery, my battalion com- mander looked for a solution. He asked the few (about 10) tank com- manders who had qualified what they had done to be successful. Some of them said that they had ad- justed their jump knobs after calibration to bring the strike of their rounds closer to center of mass of the target.

The battalion commander also heard that another battalion in the division had allowed its personnel to adjust their jump knobs, and they had shot very well. Using this infor- mation, the commander came up with a plan to qualify more tanks at gunnery by making adjustments to jump knobs in a "controlled" man- ner. He authorized adjustments based on a two-round shot group at the 1,250-meter panel. The adjust- ments brought the strike of the round within a three foot radius of center mass. The tank fired a third round at the 1,250-meter panel to verify the adjustment. If the round struck within the target circle, the -

78 ARMOR - September-October 7988

"Using the "oid" way of calibrating, even if the round struck only the edge of the panels, we made no adjustments. Then, during a hasty reticle lay, if the gunner layed slightly off center of mass, the round could miss the target. 'I

tank fired a fourth round at the 1,500-meter panel. If the round hit the panel, the tank was calibrated for that type ammunition. If the third round did not hit within the target circle on the 1,250-meter panel, the commander determined if a further adjustment was feasible, based on how the first adjustment moved the strike of the round. The battalion commander listened to recommendations from the respec- tive platoon sergeant, master gun- ner, and company commander.

The results of this gunnery were as- tounding. The battalion qualified about 44 tanks out of 58 on their first run on Tank Table VIII. That was about four or five times better than previously.

I was the towerlrange officer in charge (OIC) for the entire bat- talion's calibration, and became very familiar with the sequence. I was also the range OIC at a sub- sequent gunnery, when the battalion qualified 54 out of 58 tanks on their first run on Tank Table VI11. the

best M6OA3 tank battalion qualifica- tion rate in USAREUR.

One area of concern was the num- ber of rounds allocated for calibra- tion. The normal allotment was three HEAT and three SABOT. The modified version required four, or sometimes five, rounds per tank, per ammunition type. We found that most tanks only needed two rounds of SABOT because of the round's accuracy. The HEAT was more difficult to balance, though. We diverted some of the Tank Table VI rounds to make up the dif- ference.

Benefits were that the crews had more confidence in being able to hit targets, and it also started the gun- ner closer to center mass of the tar- get. That is to say, the strike of the round is closer to the gunner's lay.

Using the "old" way of calibrating, even if the round struck only the edge of the panels, we made no ad- justments. Then, during a hasty reticle lay, if the gunner layed slight-

ly off center of mass, the round could miss the target.

There is a direct relationship be- tween our use of adjusting jump knobs and our battalion's success. Keep in mind that not every tank needed to make any adjustments, and after two battalions-worth of jump knob adjusting, the effects on round impact were very consistent.

Captain Mark T. Hefty was commissioned from the USMA in 1983. He also attended the AOBC and AOAC. Assigned to the 1-37 Armor, 1st AD, in the FRG, he served as mortar platoon leader, tank platoon leader, tank company XO, and 53 Air. He is currently assigned as assistant S3 of the 2d Bde, 5th ID, at Fort Polk, LA.

ARMOR - September-October I988 79

When W i I I We Ever Lea r n? by Captain Andrew F. DeMario

Are we losing sight of the realities of offensive armored warfare?

History tells us that in Europe, combat in cities and forests will be the rule, not the exception.

Why aren’t we training for this possibility?

The Huertgen Forest after a bombardment in 1945. “The most skiIQii1 strategic

offerwive leads to a catastrophe if the available resoiirces are irtsirl-ficient to have the good fornine to at- tain tlie final goal wliiclt en- siires the peace for iis.” - A.A. Svec1iin.‘

“Ponder arid deliberate before yoii make a move ...“ - Sun~zu.’

“We disregard the lessons of histon,.“ - George S. Patton, ~ r . 3

“The Russians qisteitiati- callv aploited all difficiil- ties which their coiiritni prcsertted to the citerip. 111 villages, woods, arid mar- shes ... tlie Riissiaris coni- birted the tricks of itatlire with their own innate Clill- rting in order to do the greatest possible harm to the e ~ i e ~ t i ~ . “ - DA PAM 20-30, Russian Combat Methods b t World War Two.

Given that U.S. strategy today is concerned with offensive maneuver as a primary counter to enemy ag- gression, let’s address some of the concerns about our preparatory phase in carrying out such a doctrine in Europe.

Before setting out to attack, a com- mander must take into account many considerations; among them, that he has a thorough knowledge of the battlefield; that he recognizes the expenditure rate of munitions and .fuel in an offense; that he selects correct types and quantities of weapons and other equipment; that he ensures he has enough sol- diers, and that they have the skills needed to carry out the mission; and, in addition to all this, that he correctly anticipates enemy respon- ses to his projected moves.

Let’s look at the potential bat- tlefield. Examine a terrain map of Central Europe and you will see large areas of urban sprawl sur- rounded by vast woodlands and checkerboards of relatively open cul- tivated areas - each dotted with small to medium-size towns or vil- lages at virtually every road junc- tion. To a skillful defender, such ter-

rain offers many advantages. In- deed, in an era of vastly-improved target acquisition capability, en- hanced weapon accuracy, and target effects of improved munitions, any combat leader worthy of the name who does not take advantage of the cover and concealment that forests and/or urban areas provide, will soon pay a heavy price for his lack of insight.

The history of European warfare, especially during the two World Wars, is one of fighting through city after city, town after town, village a h village, forest after forest. There is absolutely no reason to ex- pect that another war in this area will be any different; in fact, the Germans acknoledged the Soviets as masters of defense in such areas.

Consider the following testimony from some of those Germans:

“If defeensiiv or offensive actions cost the Gentiaris about the same toll of casiialties as the Russians, the result in the long nin had to be art CY-

haustioit of Geiittary’s war potential merely in tentis of liirrtiart lives. All the inore inevitable was that firtal

20 ARMOR - September-October 1988

resirlt i f Genitariy 's qziaittitatise iit- feriorip iii ittartpower coiild riot be onset by a qualitatirv siiperiorip iii iiiatcriel. rite Riissiarts appeared to be well aware of these coiisidera- tioiis. niq chose for their ittost deter- iiiiiied eflorts swaiiip, forested, ter- rain wlicre siiperiont?, iii ittaleriel was least eljctiw." - D A P A M NO. 20- 2w4

"Bv iiiiscnipiiloiis iise of the civiliaii popiilatiort ... he created well-dcvel- opcd iOIteS iit depth ... I$ because of the terraiii, lie cyected tank attacks, the citeniv developed poiitts of inuiit eflort. He was ven~ adept at rising vil- lages as strong poiitts. Wltercver lie coiild, he set iip jlaitkiitg weapoits ..."

"nte Riissiaris were veni adept at prcpariiig iiihabited places for dcfeiisc. 111 a short time, a village woirld be corirvrtcd into a little fortress ... ''