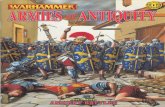

Armies of the Ancient Near East

-

Upload

matmohair1 -

Category

Documents

-

view

6.543 -

download

40

description

Transcript of Armies of the Ancient Near East

Armies of the Ancient Near East 3,000 BC to 539 BC Organisation, tactics, dress and equipment. 210 illustrations and 9 maps. by Nigel StiUman and Nigel Tallis Egyptian Old Kingdom, Middle Kingdom, New Kingdom, S,itc, libyan, Nubian, Sumerian, Akkadian, Eblaitc. Amoritc, HammUl1lpic lhhylonian, Old Assyrian, Human, MilaMian, K.ssitc, Middle: Assyrian, Neo Assyrian, Neo Babylonia n, Chaldun, GUlian, Mannatan, Iranian, Cimmerian, Hyluos. Canaanite, Syrian, Ugaritic, Hebrew, Philistine, Midianitc Arab, Cypriot, Phoenician, Hanian. Hillile, Anatolian, Sea Peoples, Neo Hinile, Aramaun, Phrygian. Lydian. Uranian, Elamilc, Minoan. Mycenaean, Harappan. A WARGAMES RESEARCH GROUP PUBLICATION INTRODUCTION This book. chronologically the finl in the W.R.G. series, attempts the diflkulltaP: of ducribingl he military organisa-tion and equipment of the many civilisations ohhe ancienl Near East over a period of 2,500 years. It is du.slening to note tbatthis span oftime is equivalent to half of all recorded history and that a single companion volume, should anyone wish to attempt it, wou.ld have to encompass the period 539 BC to 1922 AD! We hope that our researches will rcOca the: .... St amount of archacologiaJ, pictorial and tarual evidence ..... hich has survived and been rW)vered from this region. It is a matter of some rcp-ct that tbe results of much of the research accumulated in this century has tended to be disperKd among a variety of sometimes obscure publications. Consequently, it is seldom that this mJterial is aplo!ted to its full potcoti.al IS a source for military history. We have attempted 10 be as comptcbensive IS possible and to make UK of the lcuer known sourcCI and the most recent ruearm. Since, although scveral works have on the military aspectS oflhe: benerknown general ' Biblical' nations in some depth, other nations, such IS MitaMi and Urartu, which probably had a greater impact in terms of military developments, hive remained in comparative obKurity. Previous research has also tended 10 focus on the better documented periods while the later dynutiCi of Egypt and the: Early Dynastic and Akkadian periods in Muopotamia for aample, are often summarily dealt with. Within tbe usually accepted ceographical limits of the Near East (Anatolia, Syria, Egypt, the Levant, Mesopotamia and Iran) _ have included the Aegean civilisations because their military orpniAlion and equipment ..... ere dosely related to their Ncar Eastern contemporarin and because It times they played a signiflcant pan in the politia of the re,ion. For the ,eneral reader the nature of the evideo with which we are dealin, often presents problems of interpreta-tion. Ancient styles of an appear unusual and di$toned to the modem eye, the: anistic principles and aims of ancient anisllare frequently not our own. M regards written evidence, we do not pouess the type of histories and military manuab that researches ofiuer ages can dnw on. Instead, one musl utilise the often equally valuable royal annals, chrooklcs, letters, commemorative stelae and all manner of bureaucratic evidence in order (0 ,lean items or military relevance. That many nations were fully competcot in mJtten of organisation, tletia and drill is clear from the Idministrative and economk tats which were conamed only with day to day reality. Obviously, ..... hat can be Aid concerning the various nations ofthc Near Easl at diffuent periods depends on the nature and amount ofthc IUMv' inC cvidencc. HoftYU, this evidence is subject 10 cmtinual iDCale and rc-inttrpmllion IS arch:teoloPcal in\utiptioD in the repon procrCIKI. For those readers who wilb to pursue tbe subject fuMer we have included I bibliography Illhe bKlt ofthc booIt.. It. lenph well illustrates the IJlUI of infomtation lvailable. In ,eneral it lists only those works either of most usc during out research or those most nsily available for the ,eocral reader, Ind we ofTet our lpolOCicsto tbose tcholtn who were Dot' included, but whose works provided maoy valUlble inai,htl into this period of military history. We would like to thank Phil Barlter and Bob O' Brien ofW. R.G. for livin, us the: opponunity to write this boolt, and for Iheir great patiencc during the liter stages of the work. N. R. Stillman, N. C. Talli s October 1984 Note OD Term.laololY Copyrighl 1984 N. R. Slillman and N. C. Tallis Military terminolOl)', in the lanJUagcs of the nations concerned, appctn throughout in ittlic. These (emlS often defy adequate tran.llllon, .Ithough Iheir context in ancientlexu indicates their meanin,. In DUny CIJCS it is from the intensive study of such terms thlt mi litary organisa tions can be reconstructed, it is therefore most relevant to include them_ El}'Ptiao terms have been rendered II Egyptologists would pronounce the c:oruonantal skeleton writ-ten in hlc:roc.Iyphic and we have followed the convenlion of rendering the Sumerian in capitals with stpartte syllables. Fonunltciy the ocher lanrua,es can be rendered directly. PbocOKl and printed in England by Flu:iprinl Ltd., Wonhin" SIWCX 2 CONT ENTS P.,. INTRODUCTION ......................................... .. ........ ...... 2 ORGANiSATION ............... . ...... .... . . ............... . ...... .... ........ 5 Egypt .............. . .. . .. . . . .. . .... . . .. .... 5 Libyans ........... . . . . .... ............ .. . .......... 13 Nubia ..................... .......... .................. ..... 13 and Akkad ................. .... ................ ...... .. .. 15 Old Babylonian and Old Assyrian Kingdoms .............. . ...... ... 20 Milanni and Mesopotamia .... . ............................. .. .. 23 Assyria ..... . ............................................... .... 26 Babylon ....... ...... ......... .................... . ........ 32 Canaan and Syria ............... ..... ... . ....... 32 . .... .................................. . ..... 36 ............................................. .... 38 Phoenicia and Cyprus .............. . .. . ... .... .... 38 Anatolia and ......................... ......... 39 Sea Peoples ................... ... ......... .. ... .. .. ........ 42 Neo-Hiniles and Aramaeans ..... .... . .... . ....................... 43 Phrygians and Lydians .............. . ... .. . . . ... ...... 46 Uranu ............................. .................... ....... 46 Elam ............ . .................... . ..................... ... 47 The ............... , ........ . " .. , . . ,' ... ".. . ...... 48 Indus ... , . .. , .. .. , ... , ... ,........... . ........ . ..... 53 TACTICAL METHODS ..................... . .......... . . ... .... . .... . ......... 53 Egypt .", ... , ....................... .. .. . , ... ................ 53 Libyans and Nubians ................ .. , .. . ... , . . . ........ . ..... 58 Sumerian tactics ..... . ......... , ........ ,., ... ,.... . . .. ...... ... .... 59 The Old Babylonian and Old Assyrian Kingdoms. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 59 The Mitannians and Kassites .......... , ... ,............. ............. 60 The Assyrians .................................... . .. . ... . .... 60 The Babylonians ............... . .... ...... . .... . ..... . .. 62 ........... . . ...... ...... . ........ . ... ....... ..... 63 Canaan and Syria ................ . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63 tactics ..................... . . .... . .... . ... .... 64 and ...................... ..... ...... 65 Minoans and ........ . ........... . .. , . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66 The Mountain Kingdoms ............ .. . ... ... . ...... . ... 67 Nomads ................... .. . .. . . ............. .... ... 68 MAJOR BATTLES OF THE PERIOD ....... . . .. . .. . ... . . .. . .... .. ............ .. 69 DRESS AND EQUIPMENT ................. .. .... ... .... . ...... . .... . .. ....... 91 SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY ..................... . . ................. . ............ 203 CHRONOLOGICAL CHART 208 3 NILE DELTA EGYPT AND NAUKRATIS , G UI NUBIA Lower Egyptian Nomes Egypt Upper Egypt lower Egypt (' 1 1 1 Ineb-hedj f AYUMo1l 71- " Huald4topol 'l Sina i 2 Dj eba (Edlu) 2 Khem " TdlOl of' 3 Ne'hen 3 Hut-ihyt , " " , (H.ulkonpol .ll JSIWA " H4trmopol!l 4 Was et (TheMI) 4 Merke .. 5 Gebtu (CopI011 5 Sa;t (Sa.d " " Upper 6 funet 6 Per- Wad jet " " Egypt (Buto, XO!l) EGYPT 7 Hut-selc.hem 7 MUEI .. ID , -. -. 8 Abedju tAbydo 8 Per. Alum "",10' tp,lhOl'l) .. ,.,.. 9 Khem- Min 9 Per-Ausor 5 - WES H"N THESES . , . , 10 Ojebo 10 Kem-We, _, OASES' , (AOw.b!l1 , 11 Shos-hot ep 11 Ka-hebes ELEPHANTINE 12 Tu-il e( 12 Tjeb-nelJer --IXM""yIOi I '" CHHln 13 SOU! 1Al rul) 13 funu (H4tI.opo/,,) NUBIA 14 Qu IeUIU } 14 1jel 15 Khmun 15 8o'h Wawat lHumopol,,) 16 16 Hebenu Djedjef tc)ty. _l 17 Ko-Sa 17 8ehutet lC,nopoI") Buhf" _ -< Medj.y 18 18 Per-8ostet H,pponul (Bubuml 19 19 Djane! 1T1llt11 10.,.,n< II 20 Henen-nesut 20 Pe,-Iopdu Kush fHt:r,kkopol.l) 21 N./opohl Fayum,' AM.OdIe-I" 22 /(In,IIIOI'I'I ' " n ld' Prow"", . E,'(fIt '''' "amu.o: Abu, lunu, Khmun EU, .... ,,, LA REACH 4 ORGANISATION EGYPT THE OLD AND MIDDLE KlNGDOMS The basis of civil and mil itary organisation was the 'nomes' or provinces. These originated as prehistoric tribal districts which combined 10 form the kingdoms of Upper and Lower Egypt. 'The Two Lands' wcrc united into one country around 3000 BC, by the legendary King Menes. He wu possibly HOT-Aha ('Fighting-Falcon'). E:.Jch nomt wu administered by a hat)Nlo meaning 'hereditary-noble' or 'nomarch' , The Names The general reserve of young men eligible for conscription was known as djamu. and from this were drawn those eligible for mil itary service, known as (youthful recruits). In addition there were hereditary profes-sional soldiers called D."QUlyu (warriors) who WOtt red ostrich plumes in their hair. unain highly ,rained soldiers werc called mOljIJI, offen uanslated as 'shock-troopll ' . Raising and mining of recruits was probably the responsibility oftbe lrnN.nu'Mjrv (Commander of Recrui ts) a function which was usually performed by the nomlrch. The Middle Ki ngdom Nomarch, Thuthotep, records the muster of the 'youthful r:mit s of the West of the Hare Nome', those of the EaSt of the Hate Nome, and also the 'youths of the warriors of the Hare Nome'. Thus nomes that were si mated asuide Ihe Nile had an aUlomalic division of lroops int o at lt3st IWO bodies. The 'youlhs of the warriors' refers to the muster of the next generation of hereditary soldiers eligible for service. The ' lnstmctions for King Merykare' (composed by Khety of the 10th Dynasty for his son), menti on trull recruits 'went forth' althe age of20. The mmjar, or shock-troops, had tbeir own commander; the mmjar (Commander of shock troops). The various types ofuoops available in the nomes refleets the fact lhat many of the 'reemin' would bt mainly employed as a source oflabout. Good soldier material would have been selected from the youths recruited from the peasantry, 10 be trained and formed into units to sup-plement the hereditary soldiers. The hereditary soldiers were perhaps a surviwl from the predynastic organisation of the nome. The ordinary recruit may han had a limited term of service while the warrior his father and served throughout his act ive life_ This system continued up to the btginning of the New Kingdom, for Ahmose, son-ofEbana, states in his tomb inscription; ' my father was a soldier of the King ... Sekenenre ... then I was a soldier in his stead, in the ship, The Wild Bull, in the time of . .. Nebpehtire (Ahmose I)'. Nomarchs were required to supply contingents for national eITons when requested by the king, and normally led them on campaign as thei r commanders. In the reign of Senusret I (1971-1926 Bq, Amunemhat of the Oryx nome took 400 'of all the most select' of his trOOps on the king's campaign intO Nubia, He took 600 'of all the bravest of the Oryx nome' on a subsequent campaign led by the Vizier SenusreL Nome contingents would wry in size according to the population of the nome concerned, This nome was situated in Middle Egypt, and larger numbers would probably bt mustered from areas such as Memphis, Thebes and the Delta where the cultivated Lands were more extensive. Nomarchs acted as the generals of the forccs of their nome. A nomarch might be: commissioned by the king [0 use his forces to carry OUt cenain tuks, such as obtaining stone from remote quarrics in the desert, or undenaking trading mission! to distant lands, Small mil it ary expeditions might bt mounted by nomarchs as pan of thei r respon-sibil ities for cenain regions or frontiers. Some nomarchs bore the tille ow, meaning 'scout-kader' or possibly even 'commander offoreigo auxiliaries'. The most notable of these was Harkhufin the 6th Dynasty who led expedi-tions ioto Africa, Their forccs were likely to include such fortign auxil iaries as Nubians and Aamu Bedouin. ProtOC1)is from tomb inscriptions show (hat nomarchs could often hold other offices such as priest, scout lcader, sole-cdge, they would achieve efficient protection for all the individual soldiers by acting togtther as a cohesive body. Such a 'shieldwall ' would be paniculariy effective against missiles. Archers opc:roted from between the ranks and files of the spearmen, seeking the protection of the shields, (200 shows an archer from the same source as 194 operating in this manner). Swords, or pakana, were long" narrow and, like all weaponry, bronn. They were bett er suited for thrusting than slashing. 1953 is a Minoan sword. It would doubtless be difficult to break into a densely packed shieldwall. AnemplS to fmd ways of doing so may have led to the invention of the figurc.of-eight' shield. This type is carried by 195 and shown in profile in 195b. It is clearly a shield that could be used more offensively than the ' tower-shield' curied by 193 and 194. It is deep and possesses a dt-flective ability. A ridge of wood or tough leatht-r Nns down the centre. The ' waist ' might allow greater usc of the thrustingsword in the 'press'. With such I shield the bearer could have a better chancc of battering through the ranks of his oppont-nts. When this type appears it is used alongside the towershitld. Perhaps only a proponion of the formation were equipped wit h them in order 10 give a 'biting-edge' to the body, bUI personal preference cannot be ruled out . 191 -194 j " ," - - ', . ' - " , ' ' .. " ... ' " . " -- - .f . , . .. .. .:' . . ;:', .:. ,:' "-. 195 a b The shields were made of oxhide, and paneTOs consisted of black. brown or buffblolchcs on a while ground. Lines of stitching visible on the from correspond 10 the machment of the shoulder-snap and frame on the reverse. The central ridge of the fi gurc-of-eight shield was generally buff, the outer edge of the rim being blue, and the inner Ige. yellow, Helmets, koroto, were m3de from 51iven of horn CUI from boars' tusks and bound 10 a leather base with leather thongs. The ef(5[ of lhe helmet worn by 193 is possibly also made or horn, alternatively, black or black and whilt horsch:iir plumes and crests coul d be :l1I3chcd. Kilts could be fringed and elaborately embroidered. Dress sometimes consisted only of coloured 'cod.pit' . The Aegean peoples werc laU, slim and a 'bronzed' complexion. Hair was very dark, wavy alld usually worn long. Burds were uncommon, but gold deathmasks from the shaftgraves of Mycenae suggest that they could Ix worn by kings. 196. MINOAN AND EARLY MYCENAEAN CHARIOTRV c. 1550 1250 B.C. Introduced inlo the Aegean in Ihe 161h celllUry B.C., Ihe Aegean chariol soon began 10 differ in terms of delail from the NearEaslern Iype. The fourspoked wheels remained standard for a 10llger pcriod but were made stronger and more robust. The axle was posilioned near Ihe rur of the cab, and the draught -pole was strengthened by iii second pole joini ng il horizolllally from Ihe yoke 10 the fronl oflhe cab. Both shafts were funher Strengthened by wooden suppa" or thongs. It is possible lhat Ihis second shaft c:xtended backwards wilhin the cab and curved round to join the noor, providing a panition and means of suppan for the crewmen. These: are all developments designed 10 increase: the strength of the vehicle. In Egypt and Canaan the emphasis was on lightness because: speed and manocu\' rability were requi red for a primarily skirmishing role over nat open ground. The Aegean chariOl , however, was clearly more robust vehicle intended 10 take the strain of closecombat over broken ground. 192 196 a D ~ a 0 c b 197 198 d '9] Aegean chariot warfare is 11 much debau:u subiect, the discussion of ..... hich might benefit from the appreciation thai chariO! design underv.'em signific:mt change within the period c. 1550-1150 B.C. The carliest design ..... :as a type: that has been called the 'bo)hariot', illustrated in 196a. This W,IS in usc: bet ..... etn 155{1 and 145{1 B.C. Bet ..... etn 1450 and 1200 B.C. a type: C1Illed the 'dual t"" ("') ::c