Are current land and water governance systems fit for purpose in promoting sustainable and...

-

Upload

international-water-management-institute-iwmi -

Category

Environment

-

view

191 -

download

0

Transcript of Are current land and water governance systems fit for purpose in promoting sustainable and...

Are current land and water governance systems fit for purpose in promoting sustainable and equitable large-scale agricultural investments in SSA?

Timothy Olalekan WilliamsDirector, Africa

International Water Management Institute (IWMI)

GWP-ILC-IWMI Workshop, Pretoria 15/6/2015

Presentation Outline

• Introduction and background

• Multiple dimensions of land and water governance (L&WG)

• Comparative analysis of L&WG systems across six study countries

• Guidelines for coordinated land and water governance

Introduction

• Recent wave of large-scale agricultural investments in sub-Saharan Africa

• Importance of coordinated land and water governance.

• Methodology of background study

Analysis of impacts of large scale investments in agriculture on water resources, ecosystems and livelihoods, and

development of policy options for decision-makers

Background

• AMCOW’s call for development of research-based policy options for effective management of land and water in LSALI.

• UNEP, GRID-ARENDAL and FAO enlisted IWMI to conduct an analytical study to shed light on the likely impacts of LSALI.

Analytical Approach for Background Study

1. At pan-continental level, an analysis of drivers, extent, characteristics and production activities on LSALI across SSA (based on the Land Matrix database, www.landmatrix.org).

A three-prong approach

Analytical Approach (continued)

2. A more detailed analysis of LSALI in 6 countries, Ghana, Mali, Ethiopia, Tanzania, Mozambique and Zambia, based on field-level case studies, to examine the adequacy of policy and institutional frameworks for guiding and

managing such investments.

3. A socio-hydrological simulation modeling exercise in Baro-Gilo basin in the Gambella region of Ethiopia to assess impacts of LSALI on agricultural production and water resources and evaluate trade-offs between biophysical and social objectives of multiple stakeholder groups.

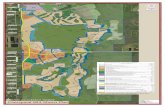

• In 2000-12, ten countries accounted for 70% of LSLAs in SSA• Area acquired in each of these countries > 100,000 ha

15%

11%

9%

6%5%4%

49%

Ethiopia

Mozambique

Tanzania

Ghana

Mali

Zambia

Others

(15%)

(11%)

(9%)

(6%)

(5%)

(4%)

(50%)

Percentage distribution of total area of LSALI in SSA by country, 2000-2012

Dimension (I)

• L&WG concerns the rules, processes and structures through which decisions are made about access to land and water, their use and management; the manner in which decisions are implemented and enforced, the way that competing interests in these resources are managed.

• L&WG encompasses statutory, customary and religious institutions. It covers ownership, rights and policies governing transactions, transfers and disputes.

Dimension (II)

• L&WG is about power, access to information and political economy.

• L&WG varies from country to country. This implies there is no one-size-fits-all solution for improved L&WG.

1. In all the 6 study countries, land and water are governed under separate but parallel policy, legal and institutional frameworks.

Results

Results (continued)

2. Within each framework, multiple property rights regimes, including state property, customary property and private property, coexist and are operated simultaneously.

3. In Ghana and Zambia state and customary property rights regimes are recognized in land matters. In Ethiopia, Mali, Mozambique and Tanzania all land is vested in the state - though this authority may be delegated to a lower-level tier of government.

Results (continued) 4. In Mali, Mozambique, Tanzania and Zambia water access and use rights are systematically included in LSALI contracts. The main requirements are for the investors to regularly pay water fees and to maintain secondary or tertiary canals. In Ghana and Ethiopia water rights are not often discussed at the time of land contract negotiation.

5. In all 6 study countries, the volume of water to be extracted by LSALI is not usually specified and water pricing, where it exists, is not related to volume extracted.

Results (continued) 6. In all 6 study countries the agencies charged with the responsibility of monitoring compliance with economic, social and environmental impacts and mitigation measures are poorly funded and lack the capacity to effectively perform their functions.

7. Parallel systems of land and water rights administration and management, poor cross- sectoral coordination of regulatory activities and inadequate capacity in relevant government agencies hampered effective and coordinated L&WG in all six study countries.

Based on an adaptation of the Land Governance Assessment Framework (Deininger et al, 2012)

• Information on land and water rights is accessible, comprehensive, current and reliable.

• Policies, laws and institutions recognize existing land and water rights and enforcement is monitored.

• Land and water planning, pricing and taxation are in place to avoid negative externalities, allow provision of services and support effective decentralization.

• Expropriation of land and water rights is done in a consultative and transparent way and followed up with quick payment of fair compensation and effective appeal mechanisms.

• Interested parties can access institutions with clear mandates to authoritatively resolve disputes • Legal, policy and institutional reforms to bring land and water administration under a single government Ministry or promote greater and more effective coordination between various agencies.

• Monitor and evaluate performance of different L&WG arrangements