Arabic Alphabet

Transcript of Arabic Alphabet

Arabic Alphabet

Semitic languages are written from right to left. Ancient Mesopotamians wrote on stones with chisels, and since that most inscribers were right-handed, it was easier and more natural to them to write from right to left (I think it still makes more sense today to write from right to left!).

The Arabic script, which is derived from that of Aramaic, is based on 18 distinct shapes. Using a combination of dots above and below 8 of these shapes, the full complement of 28 characters can be fully spelled out.

Those 28 Arabic letters are all consonants.

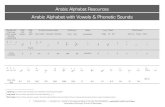

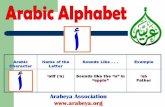

In the table below:

The first column to the right shows the Arabic letters.

The second column shows their names in Arabic. Click on the letter to hear its name.

The third column shows the Romanized version of the Arabic letters. I will use these when I write Arabic words in Roman letters.

The last column shows how the letters are represented in the International Phonetic Alphabet. This is unimportant for most people, I guess. To see these IPA figures you may need to install a font.

Some letters (the gutturals) can be hard to pronounce by non-natives, so it should be tried to pronounce them in the closest possible way to the original sounds.

International Phonetic Alphabet

Romanized Version

Name Letter

[ʔ] glottal plosive

' 'alif ل�ف�أ أ

[b]voiced bilabial plosive

as in "bat"b baa'< �ء� با ب

[t ] voiceless dental

plosiveas in "tap"

t taa'< �ء� تا ت

[θ] voiceless inter-dental

fricativeas in "thumb"

th thaa'< �ء� ثا ث

[dʒ]voiced post-alveolar

affricateas in "jar"

j jeem �م� ي ج� ج

[ħ]voiceless pharyngeal

fricativeh haa'< �ء� حا ح

[x]voiceless velar

fricativeas in German "nacht"

or Scottish "loch"

kh khaa'< �ء� ا خ خ

[d ]voiced dental plosive

as in "dark"

d daal �ل� دا د

[ð]voiced inter-dental

fricativeas in "this"

th thaal �ل� ذا ذ

[r]alveolar trillas in "run"

r raa'< �ء� را ر

[z]voiced alveolar

fricativeas in "zoo"

z zayn �ن� زي ز

[s]voiceless alveolar

fricativeas in "sad"

s seen �ن� ي س� س

[ʃ]voiceless post-

alveolar fricativeas in "she"

sh sheen �ن� ي ش� ش

[sˁ]emphatic voiceless alveolar fricative

s saad �د� صا ص

[d ˁ]emphatic voiced alveolar plosive

d daad �د� ضا ض

[t ˁ]emphatic voiceless

dental plosive t taa'< �ء� طا ط

[ðˁ]emphatic voiced alveolar fricative

z zaa'< �ء� ظا ظ

[ʕ]voiced pharyngeal

fricative" "ayn �ن� عي ع

[ɣ] voiced velar fricative(French R or guttural

R)

r rayn �ن� غي غ

[f]voiceless labiodental

fricativeas in "fan"

f faa'< �ء� فا ف

[q]voiced uvular plosive

q qaaf �ف� قا ق

[k]voiceless velar

plosiveas in "kite"

k kaaf �ف� كا ك

[l]alveolar lateral

as in "leg"l laam الم� ل

[m]bilabial nasalas in "man"

m meem �م� م�ي م

[n]alveolar nasalas in "nose"

n noon cو�ن� ن ن

[h]voiceless glottal

fricativeas in "hat"

h haa'< �ء� ها هـ

[W]voiced labialized

approximant as in "wool"

w waaw �و� وا و

[j]palatal approximant

as in "yes"y yaa'< �ء� يا ي

*Note: This figure ( '< ) means a still consonant letter 'alif '. Stillness means that the' sound is not followed by any vowel. Thus, it has an almost zero duration and does not leave the throat. Look in the pronunciation section for more information.

The 28 Arabic letters are all consonants.

However, there are vowels in Arabic of course. There are six vowels; three short vowels and three long ones. Only the three long vowels are written using the alphabet. The three short vowels have special marks which denote them.

The long vowels are letters but the short vowels are not letters.

The three long vowels are written using the three following letters: ي، و ، ا Because of this, those letters are called "weak letters;" we are going to talk about this in the vowels section.

The letter daad ض is characteristic to Arabic and does not exist in any

other language. This is why Arabs called their language sometimes the "daad language."

This ordering of Arabic letters is recent. Formerly, they were laid in the same order as that of other Semitic and Indo-European languages:

ر ق ص ف ع ث ن م ل ك ي ط ح ز و هـ د ج ب أت ش

This common ordering is a hint to the fact that all those alphabets have a common distant ancestor.

Pronunciation of Consonants

In Arabic, as in any language, proper pronunciation is best learned by imitating a native speaker. What follows here is meant to give only a general idea of how the letters sound. By carefully following the instructions here, you can arrive at a good enough first approximation to serve until you are able to listen to Arabs.

Except for the ones discussed below, the consonants are pronounced pretty much as they are in English.

Consonant 'alif ء (hamza(t))

The letter 'alif has two forms: a form that denotes a long vowel ا , and one

that denotes a consonant ء . The consonant form ء is called hamza(t) .

Phonetically, the hamza(t) is a "glottal stop". It sounds like a little "catch" in the voice. Although there is no letter representing this sound in English, the sound actually does exist.

It is the catch that occurs between vowels in the exclamation "oh - oh," (as though you're in trouble), or the separation of syllables the second of which begins with a vowel, as in the sequence "an aim" as opposed to "a name," or in "grade A" as opposed to "gray day." You should notice that little catch in the voice at the beginning of each syllable. If you did it properly and forcefully, that little catch in your voice between the two syllables is a perfect hamza(t).

In Arabic, the glottal stop is a full-fledged consonant and can appear in the strangest places: at the end of a word for example.

The traditional way to transcribe the hamza(t) in Roman characters is as an

apostrophe'.

English Phrase Arabic Online Transcription

An aim 'an 'aim

Grade A graid 'ai

However this symbolism may lead some people to ignore it, which is a problem when the letter is not followed by a vowel. I am going to use this

novel symbolism : '< for the hamza(t) that is not followed by any vowel; even if it looks funny, it is clearer.

Emphatic Consonants

(You may click on the Arabic letter to hear its sound)

Four Arabic letters: ظ , ط , ض , ص are known as "emphatic consonants".

Although there is no exact equivalent of them in English, they are not all that difficult to pronounce: it just takes a bit of practice.

The best way to do it is to start with their "unemphatic" equivalents.

For example, pronounce ص s as س S.

Now try to make the same sound, but as if your mouth was full of cotton wool, so that you have to say S with your tongue drawn back. Make the sound more forcefully and shorter in duration than a normal S. The back of your tongue should be raised up toward the soft palate, and the sound produced should have a sort of "dark" quality.

This is the letter Saad ص s .

There is a similar relationship between the following pairs:

d د d and ض

t ت t and ط

th ذ z and ظ

If you listen to native speakers of Arabic, one thing you will notice is that these "emphatic consonants" give a very distinctive sound to the language.

Kh خ (khaa'<) The letter Khaa'< is a voiceless velar fricative. It sounds like the ch in the Scottish loch or like the ch in the German nacht, but it is slightly more guttural than its Scottish or German counterparts.

Whatever you do, don't pronounce it as an H or a K. It is, better to exaggerate rather than underemphasize the guttural aspect.

R غ (rayn)

This is the the sound of the Parisian R, in French. Or, if you like, the sound you make when gargling.

The common Romanization for this letter is "gh"; but I am going to go here

with r .

Q ق (qaaf)

This sound usually gives European speakers a hard time. It sounds a bit like K, but it is pronounced very far back in the throat.

When you say the letter K, you touch the roof of your mouth with more or less the middle of your tongue. When you say a qaaf, you touch the very back of your tongue to the soft palate in the back of your mouth.

Most Europeans trying to learn Arabic have a lot of trouble doing this, and

pronounce qaaf as if it were kaaf ك . Arabs tend to be fairly tolerant of this mistake, and there are not very many words in which the difference between qaaf and kaaf determines a different meaning. Still, it's worth making the effort.

(ayn") ع "

This is a unique sound that only exist in Semitic languages. It is usually very hard for Europeans to make. Unfortunately, it is a very common letter so it must be mastered.

However, learners of Arabic can make this sound pretty well after practicing for some time. The best way to learn it is to listen to Arabs and to practice incessantly.

This letter is a pharyngeal voiced fricative. That means that the sound is made by constricting the muscles of the larynx so that the flow of air through the throat is partially choked off. One eminent Arabist once suggested that the best way to pronounce this letter is to gag. Do it, and you'll feel the muscles of your throat constrict the passage of air in just the right way.

The sound is voiced, which means that your vocal cords vibrate when making it. It sounds like the bleating of a lamb, but smoother.

Russell McGuirk described this sound in his "A Colloquial Arabic of Egypt" saying " if you sound like you are being strangled you will have mastered the 'voiced pharyngeal fricative." He also says to try to swallow the sound "ah".

An American learner of Arabic explained his technique as follows:

Reduce your air flow by putting pressure on your throat with your hand, or, in essence, choking yourself. Start by saying the sound 'ah' as in father and then hold your open hand out in front of your face with the palm facing the floor -- in other words parallel with the floor. You will be looking at the profile of your index finger and your thumb. Now, while saying the sound 'ah' slowly move your hand towards your throat, above the Adam's Apple or below where the chin meets the neck. When your hand reaches your throat keep pushing (slowly) until it sounds like you think it should. I looked at my profile in the mirror while doing this to try to judge how far I push my hand into my throat, but it is difficult to tell -- maybe anywhere from a half inch to an inch.

Anyway, this is a good exercise just to get you familiar with producing the sound, the muscles that produce it, and what they need to do to produce it. Eventually, with enough practice, one should be able to produce the sound without choking him/herself.

H ح (haa'<)

The last one, this letter sounds much like a very emphatic H. Imagine that you've just swallowed a spoonful of the hottest chilies imaginable: that "haaa" sound that results should be a good approximation of haa'<.

Strictly speaking, haa'< is an unvoiced version of "ayn. In other words, it is made just like the "ayn, except that when you say "ayn your vocal cords vibrate, but when you say haa'< they don't. (In English, for instance, t and d are exactly the same, except that t is unvoiced and d is voiced: your vocal cords vibrate when you say d, but not when you say t.)

Don't worry too much if you can't get qaaf, "ayn, and haa'< right away. Quite a few learned people have struggled for decades with them.

As a first approximation, you can pronounce qaaf like kaaf, "ayn like hamza(t), and haa'< like haa'< (like an English h). But this should be only a temporary measure, more or less equivalent to the Arab who says "blease" instead of "please"' (as you will have noticed, there is no letter P in Arabic).

Words

In most languages, putting letters next to each other simply creates a word.

However, In Arabic, putting letters as they are in a row does not create any word.

ر ح This is not a word ب

Ancient Arabs (or more precisely, Arameans) saw that it made more sense to join the letters of each word together, so the previous word will look like:

:Now this is a word, and it means ـرـحب = ر + ح +ب

sea

So to write and read Arabic you will have, in addition to knowing the letters, to know how each letter is joined when it is at the beginning, middle, or end of the word.

Examples:

Day مويـ = م + و +ي

Notice here that one of the letters و was joined from the right but wasn't joined from the left; this happens.

Book بـاتكـ = ب + ا + ت +ك

Supper ءـاشعـ = أ + ا + ش +ع

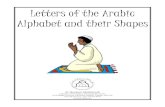

Figures of Joined LettersLetter

End Middle Beginning

Look below أ

ــب ــبــ بــ ب

ــت

ــتــ تــ ــة ت

ة

ــث ــثــ ثــ ث

ــج ــجــ جــ ج

ــح ــحــ حــ ح

ــخ ــخــ خــ خ

ــد ــد د د

ــذ ــذ ذ ذ

ــر ــر ر ر

ــز ــز ز ز

ــس ــســ ســ س

ــش ــشــ شــ ش

ــص ــصــ صــ ص

ــض ــضــ ضــ ض

ــط ــطــ طــ ط

ــظ ــظــ ظــ ظ

ــع ــعــ عــ ع

ــغ ــغــ غــ غ

ــف ــفــ فــ ف

ــق ــقــ قــ ق

ــك ــكــ كــ ك

ــل ــلــ لــ ل

ــم ــمــ مــ م

ــن ــنــ نــ ن

ــه ــهــ هــ هـ

ــو ــو و و

ــي ــيــ يــ ي

Joining Figures of Letter أ(hamza(t)/consonant 'alif)

Beginning أ إ ا

Middle ء ـؤ ـئـ ـأ

End ـئ ـأ ء ـؤ

Joining Figures of Letter ا(weak/extended/vowel 'alif)

Beginning ----

Middle ـا

End ـى ـا

Detailed information on the usage of different joining figures of letter 'alif is available on this page.

Special Figures

آ = ا +أ

ـأل /أل =أ +ل

ـإل/ إل =إ +ل

ـال /ال =ا +ل

Vowels

The Arabic 28 letters are all consonants. Nonetheless, Arabic have six vowels.

There are three short vowels and three long vowels.

Short vowels appear only in pronunciation but do not have letters that

represent them in writing. I will be Romanizing the short vowels as: a , i ,

and u .

Short vowels are sometimes denoted with special marks that appear above or

below the preceding letter. These marks are: , , respectively.

These marks are rarely seen in real life, so you should not count much on them.

The three long vowels will be Romanized as: aa , ee , oo .

Long vowels are denoted in writing with the letters: ا ، ي ، و respectively.

But we already know that these three letters are the three consonants: ' , y, w .

Therefore, these three letters can denote both the consonants and long

vowels. This is why they are called the "weak letters" ة�¦ �ع�ل ال cو�ف cرcح .

Arabic Name Arabic Online Romanization Vowel

fatha(t)

opening (of lips)�حة� فت a

Short A

aAs in "accept,"

"ascend"

x

'alif mamdooda(

t)

extended 'alif

�ف� ألمم�دودة�

aaLong A

āAs in "man,"

"can"

ا

kasra(t)

breaking (of sound)

رة� كس� iShort I

iAs in "sit," "hit"

x

yaa'< mamdooda(

t)

extended yaa'<

ياء�مم�دودة�

eeLong I

īAs in "feel,"

"deal"

ي

damma(t)

joining (of lips)ضم¦ة� u

Short U

uAs in "put,"

"foot"

x c

waaw mamdooda(

t)

extended waaw

واو�مم�دودة�

ooLong U

ūAs in "sure,"

"roof"

و

sukoon

stillnessسcكون� -----

No following vowel

As in "stay,"

"drag"

x �

* "X" means any consonant preceding the short vowel.

The three weak letters are joined when they denote long vowels just like when they denote consonants. There is no way to determine between the two possibilities by just looking at the word if you do not know which one is the one.

However, the exception is the weak ا .You have seen that it is missing the

sign ء .

If the 'alif has that sign, this means that the 'alif is definitely a hamza(t)

The hamza(t) is the consonant form of 'alif (the glottal stop, the . هم�زةzero-duration A vowel).

If the 'alif is not carrying the sign of hamza(t), then it must be a long vowel A EXCEPT when it occurs first letter in the word. In that case, the 'alif is a hamza(t) (consonant), but it is a special type of hamza(t) that is pronounced only when it is the first sound coming out of the mouth (i.e. when you begin speaking by pronouncing that hamza(t) ). This hamza(t) is called the

"connecting hamza(t)" الوص�ل� cهم�زة . The other outspoken hamza(t) at

the beginning of a word is called the "disconnecting hamza(t)" cهم�زة .that one is always pronounced ;القط�ع�

So a single 'alif can never denote a long vowel when it is the first letter of a word; there is no Arabic word that begins with a long-vowel-denoting 'alif. This is why the table of joining figures did not a have a figure for long vowel 'alif at the beginning of the word.

The hamza(t) is not a weak letter. The weak 'alif is only that 'alif which is not the first letter of a word and which doesn't carry the sign of hamza(t).

The ي and و have no such differentiation. The ي and و are always called weak letters, whether they were denoting long vowels or not.

Short vowels are called in Arabic "moves" ت�� . حركا

Long vowels are called "extensions" cف cالمد§ أح�ر .

A letter that is followed by a "move" is called a "moving letter" ف� ك� حر� مcتحر§ .

A letter that is not followed by any vowel is called a "still letter" ف� حر��ك�ن� .سا

The mark for "stillness" is: x The three letters that indicate long vowels (extended letters) are always still, i.e. never followed by any short vowel (move).

The letter that precedes any extended letter must be followed by the short vowel that corresponds to the extended letter.

Extended LetterCorresponding

Short Vowel

ا a x

ي i x

و u x c

Thus, the extended letter is always a still letter and is always preceded by the corresponding short vowel. This the definition of long vowel. Any weak letter that is still and preceded by the corresponding short vowel indicates a long vowel.

———————————————————————————————

Extra Note You will see when you get deep enough in Arabic that Arabic does not have

real long vowels but only the three short ones (a, i, u). The long vowel I is composed of a short I and a still consonant Y (iy = ee). The long vowel U is composed of a short U and a still consonant W (uw = oo). The long vowel A is composed of a short A and a weak 'alif that represents another short A (aa). The second short A is not a consonant 'alif in this case. However, this weak 'alif is not an original letter and it is always transformed from either a consonant Y or W (ay → aa , aw → aa); thus, again we have a long vowel that is composed of a short vowel and a following still consonant, but the consonant here is disguising in the form of a short A.

Arabic Long Vowels

aa � ـا

iy = ee ـي�

uw = oo ـو� This information will become useful later, but in the beginning, it is good idea to stick to the principles mentioned above without diving in these details.

———————————————————————————————

Here is the Romanization scheme for the hamza(t) with the vowels:

You may click on the letter to hear its sound

Romanization for letter أ

'a With a short A أ'u With a short U cأ'i With a short I � إ

'aa With a long A آ'ee With a long I إي'oo With a long U أو'< With no vowel �أ

There are some special transformations that often involve the hamza(t) :

'a + '< = 'a'< → aa � + أ �= أ آ ← أأ

'i + '< = 'i'< → ee � � + إ ـ� = أ �ئ إ

إيـ ←'u + '< = 'u'< c � + أ cؤ� = أ أو ←أ

→ oo

These transformations were meant to facilitate pronunciation.

►DiphthongsA diphthong means two vowels following each other and pronounced as one syllable. For example, the word "eye" is pronounced as a diphthong composed of a long A followed by an i (āi), and the word "mail" contains a diphthong composed of a long E and an i (mēil). Diphthongs are very common in English. In Arabic however, diphthongs are few. Important diphthongs in formal Arabic are the following:

aw ay aaw aay

►aw / aaw sound similar to "mount", "doubt" or the German "aus."

So the Arabic word waaw sounds: wow!

►ay / aay sound similar to "my", "dry" or "Einstein."

Click on the example to hear the pronunciation:

Pronunciation Example

'aw أو�

'ay أي�

Diphthongs like iw or uy do not exist in Arabic. When the combination iw

occurs, it is transformed to other things (usually to iy) and the combination

uy is usually transformed uw.

The concept of diphthongs is a western concept. From an Arabic point of view, the diphthongs are not combinations of vowels but combinations of

vowels and weak consonants (w and y are not vowels in Arabic but consonants, because when you say "wide" and "yard" you are pronouncing consonants not vowels). For example, diphthongs such as the one in the word "Iliad" are written in European languages with two vowels, i and a. If we were to transcribe this diphthong in Arabic, we would need to use three transcription symbols not just two:

Western Transcription Arabic Transcription

iliad iliyad � �ل د�يإmyriad miriyad د��يم�ر

The Arabic transcription identifies a full-blown consonant y between the two vowels i and a, whereas the western point of view is that this is a diphthong composed of two vowels connected by a "glide." The "glide" is a letter in

Arabic (either w or y), so the Arabic transcription system does not recognize

the western concept of diphthongs. Vowels NEVER follow each other in Arabic.

Western View Arabic View

vgvvowels connected by "glides" in

diphthongs

vCvvowels connected by weak

consonants

C: consonant v: vowel g: "glide"

In the modern spoken Arabic, the diphthongs aw and ay have evolved into

new, simple vowels. Aw has evolved into a long O (ō as in "loan") and ay

and has evolved into a long E (ē as in "hair.") This has happened in nearly all the modern dialects barring a few exceptions (e.g. modern rural Syrian dialects) where the classical vowels and diphthongs remain unchanged. Click to hear,

Modern Informal Classical/Formal Example

'ō 'aw أو�'ai 'ay أي�

yōm yawm يو�م

bait bayt �ت بي

Reading Out►'alifIf a letter 'alif is following another letter, it will be a long A vowel if it lacks the

sign of hamza(t) ا and a glottal stop (hamza(t)) if the sign is present أ .

Examples, click on the Arabic syllable to hear it:

ba'< � أ ب baa � ا ب

shu'< cؤ ش � shaa � ا شwi'<

� ئ و� waa� ا و

mar'<� ء مر� yaa � ا ي

You can see that the figure of the hamza(t) is related to the short vowel preceding it. This is explained in detail here.

Pronouncing a still hamza(t) '< may be approximated by saying an

extremely short a (or any other vowel.) If you can say an a and terminate it before it leaves your throat (zero duration,) you will have mastered the still hamza(t).

However, if the 'alif is the first letter of a word, it must be a hamza(t); a long A denoting 'alif cannot come first in any Arabic word. The difference between

when they are the first letter of a word was explained in the previous أ and اpage.

'al ل�ا 'al ل�أ'is �س�ا 'is � س�إ'un cن�ا 'un cن�أ

Arabic words cannot begin with a "still" letter (a letter that is not followed by a

vowel); this is why the ا hamza(t) is added in front of certain types of words that otherwise would be beginning with still letters.

A common terminal structure in Semitic nouns is a long A vowel followed by a

weak letter (-aaw or -aay). In Arabic, the final weak letter of such structures is almost always turned into a glottal stop or hamza(t). Hence, the

structure -aa'< ءــا is common in Arabic nouns.

Examples, click on the word to hear it:

Original Form (Not Used) Noun

maay �ي ما maa'<� ء ما

water water

samaay �ي سما samaa'<� ء سما

sky sky

masaay �ي مسا؟

masaa'<� ء مسا

evening evening

*Note: the classical teaching of Arabic grammar considers the original endings of these three nouns to be -aaw not -aay.

The final hamza(t) of the combination -aa'< is often dropped in the

modern spoken dialects so that it becomes just -aa.

When a long A vowel (aa) occurs terminally in any word, it will often not get full pronunciation but it will have shorter duration than usual. This shorter duration can be described as a middle duration between the durations of a

short A (a) and a long A (aa). However, it will often sound closer to the

duration of a short A than to a long A. This is why a terminal aa is called in

Arabic a shortened 'alif �مق�صcو�رة �أل�ف .

The other long vowels (ee and oo) will also be shortened when they occur terminal in words, and they will often sound closer to the corresponding short

vowels too (i and u).

►Waaw & Yaa'<

A letter و or ي following another letter can be denoting a long vowel or not

depending on the short vowels. A long vowel-denoting و or ي must be still (not followed by a vowel) and preceded by the corresponding short vowel.

Examples, click on the word to hear it:

kabeer� �ر ي كب

bayt �ت ي ب

big house

l-ee� � ي ل

layl �ل ي ل

to/for me nighttime

'aqoolcل و أق�

'uwaafiq c �ف�ق و أ ا

(I) say (I) agree

►Taa'<

The letter taa'< t has two versions at the end of a word:

An "open" version ـت

A "tied" version ـة

The tied taa'< cو�طةc ب المر� cء� ¦ا �ت is always preceded by a short A (-at); it الoccurs in nouns (and adjectives) and often serves as a feminine marker in singular nouns, but it can also occur in verbids and irregular plural nouns without being a feminine marker. This kind of taa'< is dropped from

pronunciation or pronounced as -h rather than -t when it is the last thing

pronounced, but it is pronounced fully as -t when it is followed by other talking. This is similar to the French "liaison."

The open taa'< cء� ¦ا �ت cو�حةcال �مف�ت ال occurs in the end of some conjugations of perfective verbs and pronouns, but can also occur at the end of some rare

nouns as a feminine marker (e.g. ت�� �ن cخ�ت� , ب أ ). This kind of taa'< is always

pronounced -t.

No Pause Pause

-at -at ـت

-at -ah / -a ـة

Doubled letters

One last thing remains about Arabic transcription, which is this mark: xIt is called shadda(t) شد¦ة� = "stress." It indicates double consonants with no vowel in between (i.e. the first consonant is still). E.g.

م± = م + مm + m = mm

Examples, click on the word to hear it:

Nation 'umma(t) م¦ةc أ

Female cat qitta(t) ق�ط¦ة

Accent and StressAccent is just as important in Arabic as in English. In English, it is usually impossible to tell which syllable of a word should be stressed, and English is especially complicated in this, since the stress can fall on virtually any syllable, whereas in most languages there, are restrictions on where accents are allowed to fall.

The best way of getting a sense of the stress patterns of any language, of course, is to listen to native speakers and to build up an intuitive sense of rhythm for the language. This is just as true for Arabic as for any other language. But there are some clear guidelines about Arabic stress.

The first thing to note is that Arabic syllables are divided into two kinds: long and short. A short syllable is simply a single consonant followed by a single short vowel. The word kataba = "(he) wrote" for instance, is composed of three short syllables: ka-ta-ba. Any syllable that is not short is considered long.

There are various ways a syllable can be long: a consonant plus a long vowel; a consonant plus a diphthong; a consonant followed by a short vowel followed by another consonant. For instance, kitaab = "book' has two syllables, one short ki- and one long -taab. Another example: maktaba(t) = "library" has three syllables. The first one is long mak-, the second short -ta-, the third short -ba. Finally, take maktoob = "written;" it has two long syllables mak- and -toob.

Now, the basic rule of Arabic stress is this: the accent falls on the long syllable nearest to the end of the word. If the last syllable is long, then that syllable is stressed: kitaab, accent on the last syllable. If the second-to-last syllable of a word is long and the last is short, then the second-to-last syllable is stressed: 'aboohu = "his father," accent on the second-to-last syllable. If there is no long syllable in the word (like kataba), then the accent is on the third-to-last syllable. This will be the case with the great majority of past verbs, since these usually take the form of three consonants separated by short vowels (kataba, darasa, taraka, and so on - all accented on the first syllable).

Last point: the accent is not allowed to fall any further back than the third syllable from the end. So if you have a word of four (or more) short syllables, the stress has to fall on the third syllable from the end. For example: katabahu = "(he) wrote it" has four short syllables; the stress will therefore fall on the third syllable back: katábahu.

While we're on the subject of accent, we should note one other thing: in Arabic every syllable, long or short, should be clearly and distinctly pronounced, given its due weight. In this Arabic is like Spanish, and not like American English. Syllables do not disappear or get slurred just because they are unstressed.

Rules of Pause

In Arabic, the pronunciation of word endings differ when they are followed by other talking (the state of junction cوص�ل� from when they are the last thing (الpronounced, or when they are followed by a pause (the state of pause cوق�ف� .(ال

We have seen an example of this already when we talked about the

pronunciation of the tied taa'< ـة , which is pronounced -at when not

terminal in pronunciation, and -ah or -a when terminal in pronunciation or followed by a pause.

Another important rule of pause in Arabic is that any terminal short vowel of any word must be dropped from pronunciation when followed by a pause.

For example, a terminal -lu , -ba, or -ni will be pronounced as follows:

Pronunciation in state of junction

(not last thing pronounced)-lu -ba -ni

Pronunciation in state of pause(last thing pronounced) -l -b -n

Note that the rules of pause regard only the pronunciation but not the transcription of any word ending.

The rule of dropping a terminally pronounced vowel regards only the short vowels, but not the long vowels. We mentioned before that terminal long vowels are usually shortened in pronunciation, but this happens in all states not only at pause.

In Arabic terminology, letters that are followed by short vowels are called "moving letters." Letters that are not followed by short vowels are called "still letters."

The rule says that the final letter pronounced of any word must be "still" and cannot be "moving." A final moving letter must be turned into still by dropping the short vowel following it in pronunciation (which is not a letter itself— short vowels are not letters in Arabic).

This is the classic Arabic saying:

"Arabs do not stop on a moving" ²ك مcتحر§ على� cتق�ف ال cالعرب.

ExerciseTry reading the following words on your own, then you can hear them by clicking them. (Ignore the rules of pause only for this exercise.)

(He) wrote كتب(He) traveled سافر

(He/it) was brought ح�ض�رc أ(He/it) was said ل� ق�ي

Color لو�نAppearance ظcهcو�ر

School مد�رسةYour opinion cك �ي رأ

Roots

In Indo-European languages such as English, the infinitive is usually the basic from of the verb of which the rest of the forms are derived.

For example, the infinitive "to talk" is the source of many derived words:

Talk Infinitive

Talking Present participle

Talked Past participle

Talk Present simple

Talked Past simple

Talk Noun

We see that the main stem of the infinitive stays preserved, while the inflection works by affixing other parts to the stem. At least it is so most of the time.

Unfortunately, in Semitic languages things are a little bit more complex than that.

In Arabic, the basic source of all the forms of a verb is called the "root" of the

verb الف�ع�ل� cجذ�ر .

The root is not a real word, rather it is a sequence of three consonants that can be found in all the words that are related to it.

Most roots are composed of three letters, very few are of four or five letters.

The root can be easily obtained from the 3rd person masculine singular past form (the perfective) of the verb.

Look at these roots:

Meaning of Verb Root 3rd person masc. sing. past (perfective) verb

(He) did F " L ل ع ف fa"al(a) فعل

(He) wrote K T B ب ت katab(a) ك كتب

(He) studied D R S س ر daras(a) ددرس

(He) drew (a picture) R S M م س ر rasam(a)

رسم

(He) ate ' K L ل ك أ 'akal(a) أكل(He) knew " L M م ل ع "alim(a) �م عل

(He) was/became bigger K B R ر ب ك kabur(a) cر كب

(He) rolled (something) D H R J ج ر ح د dahraj(a)

ر دح�ج

You see that the root is not a word; it is just a sequence of consonants. The consonants of the root are separated by different vowels in different words. They can also be separated by other extra consonants that do not belong to the root.

The root is used to make all the forms of a verb. It is used to make nouns as well.

Each root pertains to a certain meaning, e.g. K T B ب ك ت pertains to

"writing."

See the following example:

MeaningWords derived from the root ت ك

ب

Verbs

(he) wrote katab(a) كتب≈ (he) was/became written kutib(a) �ب cت ك(he) was/became written 'inkatab(a) �كتبان(he) made (somebody)

write kattab(a) ¦ب كت(he) made (somebody)

write 'aktab(a) �تبأ ك(he) exchanged writing with→ (he) corresponded with kaatab(a) تباك

(he) exchanged writing→ (he) corresponded takaatab(a) تباكت

(he) wrote himself→ (he) subscribed 'iktatab(a) �ا تبتك(he) sought writing 'istaktab(a) ت �س� �تبا ك

Nouns

writing katb �ب كتwriting

→ book/dispatch kitaab �ت باكwriting kitaaba(t) �ت اك ةبbooklet kutayyib cت §بيك

writing (man)→ writer kaatib �باك تwritten

→ letter maktoob �تم بوكdesk/office maktab �تبم ك

library/bookstore maktaba(t) م �تب ةك

phalanx kateeba(t) يكت ةب

So basically all these words were created by taking the root ب ت and ك

adding letters or vowels to it. This is how Semitic languages work.

Almost all Arabic words are structured on roots. Words in Arabic grammar belong to three categories:

Noun cم �س� .includes pronouns, adjectives and most adverbs : اال

Verb cف�ع�ل� .there are three main verbal structures in Arabic : ال

Letter (particle) cف �حر� .small words that do not have roots : ال

So small words without known roots were not even qualified enough to carry the title of a "word" in Arabic grammar. Many of these "letters" are prepositions and they do not undergo inflection.

The letters of the root are called the original letters of a word فcاألح�رc ¦ة �ي cاألص�ل .

The variable letters that appear between the root letters in different words are called the additional letters فcاألح�رc دة� cالزائ .

The letters that can serve as additional letters are ten: ا هـ تأ ن م ل س

ي وThese letters are rounded up in the word: � �ها �ي cمcو�ن �ت you asked me" = سأل

for/about it."

There are standard patterns for adding additional letters to the root. These

patterns are called 'awzaan ن� �أو�زا = "measures" or 'abniya(t) ية� �ن �أب = "structures."

For example:

'infa"al(a) fa"al(a)

�ن �فعلا did himself/itself (he/it)فعل (he/it) did

'inkasar(a) �ن �كسرا kasar(a) broke himself/itself (he/it)كسر (he/it) broke

'insabb(a)�ن �صب¦ا

sabb(a)

poured (he/it)صب¦himself/itself

(he/it) poured

So this structure 'in*a*a*(a) has a specific sense that is different from

the basic structure *a*a*(a).

Both structures are structures of active voice past (perfective) verbs. However, there is a difference between the two that is reminiscent of the Latin or French difference between faire and se faire. The 'in*a*a*(a) structure is called a "reflexive" verb because it denotes a self-directed action. You can put so many root letters in place of the stars and you will get the same outcome.

Usually stars are not used but instead the root ل ع do" is used for" = ف

giving prototypes of different structures.

So these two structures will be standardized:

(He/it) did fa"al(a) فعل(He/it) did himself/itself 'infa"al(a) � �ن فعلا

Etymology Note: Biliteral Roots

Arabic grammar recognizes three-letter, four-letter, and five-letter-roots, but not anything more or less than that. Five-letter-roots exist only in nouns but not verbs.

However, there are several Arabic nouns that have only two consonants in them, for example:

Father 'ab أبBrother 'akh أخ

Son 'ibn �نا �بName 'ism �س�ماMouth fam فمHand yad يدBlood dam دم

The ا is not an original letter but is only a "liaison" that is added in front of some words for a phonological reason. More about this is available on this page and this one.

Classical Arabic grammarians did not recognize biliteral roots and considered them all to be modified from triliteral roots. For example, grammarians of the

classical period (8th & 9th centuries) debated whether the root of س�ما� was

و م م or س س . و

However, the truth is that Arabic indeed has biliteral roots. Moreover, there was a time at which Arabic did not have any roots but biliteral roots.

This can be shown by comparing the meanings of different triliteral roots; for example:

Proto-Root ط ق(He) cut qata"(a) عقط(He) cut qatal(a) لقط(He) cut qat t (a) ¦طق

(He) stitchedoriginal sense:

(He) cutqatab(a) بقط

(He) picked (a plant part) qataf(a) فقط

(He) took a bite qatam(a) مقط(He) dripped qatar(a) رقط

Notice that all these triliteral roots have a common general meaning, and they all share the first and second root-letters. This indicates that all these roots

were derived from a common biliteral ancestor, which is the proto-root ط . ق

Surprisingly, this is also the root of the English verb "cut!" In fact, this has to do with more than mere chance. Such basic verbs are often related to the sound that an action produces, so it is not unusual that they be similar in totally unrelated languages.

Knowing this idea of proto-roots will be very helpful in determining the original meanings of a large number of roots.

For example, knowing that there was a proto-root ط whose meaning was قrelated to cutting and to "pieces" will help us figure out easily the original meaning of the following root:

قطنqatan(a)

(he) dwelled

This verb has an odd meaning compared to the meaning of the proto-root ق However, there is another word of the same root whose meaning seems . طmore original:

قcط�نqutn

cotton (masc.)

The English word "cotton" was borrowed from Arabic in Middle Ages. The meaning of "cotton" is more consistent with the general meaning of the proto-

root, so we can easily infer that the verb qatan(a) has an altered meaning

and that the original meaning of the root ن ط ".is related to "pieces ق

Hebrew has the same root:

נ ט' ק(qaaton

(He) became small(er)

Another interesting point is that there are several roots that were derived from the same proto-root but they look somewhat different these days. For example:

(He) killed qatal(a) لقت(He) was parsimonious qatar(a) رقت

Bowel qitb � بق�تDust

→ darkness qataam �ماقت

Kind of a thorny plant qataad �داقت

These words have the proto-root ت ط which is very similar to , ق and , ق

they probably were one thing initially. Because we know the meaning of ط ق, we can easily determine the original meaning of ت .("pieces") ق

Knowing these principles will help us figure out the original meanings of countless vague roots, and it will help us avoid making mistakes like, for

example, saying that the original meaning of the Arabic root ف ر is "to ع

know." This is clearly false as the proto-root ف has a totally different رmeaning.

Proto-Root ف ر(He) made deviate haraf(a) رفح

(He) swept away, carried along jaraf(a) رفج

(He) shed (tears) tharaf(a) رفذoriginal sense:

(He) moved fast zaraf(a) رفز(He) blinked (eye)

original sense:(He) moved fast

taraf(a) رفط(He) was/became

extravagant tarif(a) ر�فتoriginal sense:

(He) transgressed qaraf(a) رفق(He) was/became funny

original sense:(He) was nifty

zaruf(a) رcفظ

So it is clear that the proto-root ف had a meaning that is related to ر"moving," "flowing," or "straightness."

As for the root ف ر : ع

عرف"araf(a)

(he) knew, became acquainted with(used for "being familiar with people, things, etc.," equivalent to the French connaître )

This verb is irregular both in meaning and structure, as it is shown in the verb section.

However, another word from the same root is:

عcر�ف"urf

comb, crest (of rooster)This word is clearly related to the original meaning of the root ("moving,"

"flowing," or "straightness"). Thus, the original meaning of ف ر is not "to عknow."

The proto-root ف was originally ف is an interesting one. The Arabic letter رa P like the English P, so it is not surprising that roots derived from the proto-

root ب ف have similar meanings to the ones derived from ر . ر

For example:

Proto-Root ب رoriginal sense:

(He) flowed sarab(a) ربس

(He) soaked (intr.) sharab(a) ربش

(He) escaped harab(a) ربه

(He) approached qarib(a) ر�بقoriginal sense:(He) departed rarab(a) ربغ

(He) leaked, flowedModern North Syrian Arabic,

borrowed from Aramaiczarab(a) ربز

original sense:(He) became improper tharib(a) ر�بذ

(He) became ruined kharib(a) ر�بخoriginal sense:

(He) became improper warib(a) ر�بو

Road darb ر�بدAll these words, and others, are related to the same meaning which is "moving," "flowing," or "straightness."

So now that we have an understanding of the original meanings of ف ر & ر we can try to answer some famous questions, like the etymology of the , ب

word "Arab" عرب�.

A German man once said that the word "arab originally meant "arid land." This became so popular that it was taught at schools in some Arab countries; but when taking the meaning of the proto-root in consideration, this meaning appears unconvincing.

Another, better, theory said that this word was altered from "abar عبر, which is related to "passing" or "traversing." This root is also the root of the word "Hebrew," and they are all related to the nomadic lifestyles of those peoples.

However, by comparing many roots derived from the proto-roots ر ب &ف it appears clearly that the original meanings of these roots were related to ,ر

"filling" and "earth" not to "moving." So the truth is that the word "abar is

modified from "arab not the other way around.

Thus, the word "Arab" originally meant a "wanderer" or a "nomad." The roots

ب ر عand ب ر .carry related meanings in several Semitic languages غ

"Pieces"

Q T ت ق

Q T ط ق

Q S س ق

Q S ص ق

Q D ض ق

K T ت ك

K S س ك

"Moving"

R B ب رR F ف ر

Quadriliteral RootsTriliteral roots were created by adding a third letter to a biliteral roots. Quadriliteral roots were mostly created by doubling a biliteral root, and sometimes by adding a fourth letter to a triliteral root.

Many examples exist on this page. We will mention here only two examples based on the proto-roots we talked about above:

Proto-Root ط ق

(He) dripped qat q at(a) � قطقط

Proto-Root ف ر

(He) flapped, fluttered rafraf(a) رفرف

Quadriliteral and Pentaliteral roots were often extracted from foreign loanwords.

Example,

A traditional Arab currency is the dirham, which is still a currency unit in several Arab countries today. A dirham was a silver coin in old times. The name of the dirham comes from the Greek drachmē or drachma. It was

Arabized to follow the standard Arabic noun structure fi"lal ف�ع�لل� .

drachmē → dirham هم د�ر�

Some triliteral roots were also extracted from foreign loanwords. An

interesting example is the word siraat �ط� meaning "a way" or "a ص�راpath." This word comes from the Latin strata = "paved road." The Latin word

was rendered into the standard verbal noun structure fi"aal ل�اف�ع� . This is

the same structure as that of the word kitaab �ت �ك ب�ا = "a book" or "a dispatch."

strata → siraat �طاص�ر

Writing of Letter 'alif

The first letter in the Arabic alphabet, 'alif, is a weak letter that has two forms,

a consonant form or hamza(t) ء ' and a vowel form ا aa (a long A or an extended 'alif ).

Vowel 'alif

The vowel form can appear at the middle or the end of words, but never at the beginning. It can assume the following forms:

Joining Figures of Letter ا (weak or extended 'alif)

End Middle Beginning

ـا ـا ----

ـى

Choosing Between the Two Forms at the End of the Word

I. Triliteral Nouns & Verbs

If a three-lettered noun in Arabic ends with a long vowel 'alif, that noun will be an irregular noun called a Shortened Noun. If a three-lettered verb in Arabic ends with a long vowel 'alif, that verb will be an irregular verb called a Defective Verb.

The common point between those two types of words is that the long vowel 'alif at the end of any triliteral noun or verb in Arabic is not an original letter or a root letter, rather it always substitutes for a different week letter.

The form ـا substitutes for a waaw ـو .

The form ـى substitutes for a yaa'< ـي .

Deciding which form to use requires knowing the root of the word. Natives and people with good knowledge of the language can usually guess the original vowel from other derivatives of the same root, like the infinitive and the imperfective verb when dealing with defective verbs, and the dual and plural when dealing with singular shortened nouns.

Triliteral Shortened Nouns

Root Original Version(Not Used)

Actual Version

" S W و ص ع و�عص �اعص

N D Y ي د ن ي�ند �´ىند

Triliteral Defective Verbs

Root Original Version(Not Used)

Actual Version

D " W ع ود ودع �ادع

R M Y م ير يرم �ىرم

II. Nouns & Verbs with More Than Three Letters

Those will always end with an 'alif of the type: ـى .

Proper name (female) �ل �ىلي(He) likes �ىيه�و

Hospital (masc.) ف تش� ى�مcس�(He) had (S.O) to stay �ق تب �س� �ىا

Such 'alif may be an original root letter, but it also may be not.

The exception is when the 'alif is preceded by a yaa'<. In that case, it will take the other form.

World (fem.) � �ايدcن

Chandelier (fem.) cر �¦يث اMirrors (sing. is fem.) � مرا �اي

However, the proper name يح�يى� will irregularly take the first form in order to be distinguished from the verb that looks like it.

Proper name (male) ي ى�يح�

(He) lives ي �يح� ا

Words of foreign origin that end with with long vowel 'alif's usually take the

form: ـا .

Proper name (male) ¦ �حن اProper name (female) �لود�ي �ك ا

Cinema (fem.) ينم �اس�France (fem.) �س �فرن ا

Italy (fem.) �ي �ل �طا �ي �إ اAsia (fem.) ي �اآس�

Geography (fem.) �ف�ي �اجcغ�را

However, there are few foreign words that end with ـى .

Music (fem.) �ق ي �ىمcو�س�

Moses �ىمcو�س

Jesus �س ي �ىع�

Matthew ¦ �ىمتBukhara (fem.)

(city in Uzbekistan) �ر cخا �ىبTitle of ancient Persian

shahs (masc.) ر ى�ك�س�

III. Particles

Particles (rootless words) that end with a long vowel 'alif are not few. As a

rule, all such particles will end with the form ـا except for the following four

particles:

To �ل �ىإOn �ىعلYes

(to a negative question)

�ىبلUntil / Even ¦ ى�حت

Writing of Letter 'alif (continued)

Consonant 'alif

The hamza(t) cهم�زة� "is the consonant form of 'alif. It is a "glottal stop الthat can appear anywhere in Arabic words, whether at the beginning, middle, or end of the word.

Joining Figures of Letter ء (hamza(t) / consonant 'alif)

End Middle Beginning

أ ـأ ـأ

إ ـؤ ـؤ

ا ـئـ ـئ

ء ء

Choosing Between the Forms at the Beginning of the Word

The regular form for hamza(t) is the one with the sign ء showing.

The variations depend on the following vowel:

'a With a short A أ'u With a short U cأ'i With a short I � إ

'aa With a long A آ'ee With a long I إي'oo With a long U أو'< With no vowel �أ

This regular hamza(t) at the beginning of a word is called the "disconnecting

hamza(t)" القط�ع� cهم�زة. This is often an original letter and it must be pronounced always.

The other type of hamza(t) which lacks the sign ءis called the "connecting

hamza(t)" الوص�ل� cهم�زة . That one is never an original letter and it is only pronounced when it is the first thing that comes out of the mouth. Arabs added this kind of hamza(t) to some words for merely phonological reasons, namely because they hated to start talking by pronouncing a "still" letter, that is, a consonant that is not followed by any vowel. The connecting hamza(t) is somewhat similar to the French "liaison."

The connecting hamza(t) has only one figure and it usually appears in the following places:

I. Verbs

The imperative of triliteral perfective verbs which don't begin with a hamza(t).

(You) do ! �ف�عل�ا

(You) write ! cب�ا �ت cك

(You) know ! �ع�لم�ا

The perfective, imperative, and infinitive of five-lettered verbs.

(He) benefited �تفعا �ن

(You) benefit ! �تف�ع�ا �ن

Benefiting �ع�ا �فا �ت �ن

The perfective, imperative, and infinitive of six-lettered verbs.

(He) usedا

تع�مل �س�

(You) use !ا

تع�م�ل� �س�

Using

ا� �ع�ما ت �س�

ل�

II. Nouns

It appears in front of some nouns. Examples of commonly used ones are:

�ن�ا ما �س� م�ا �س�two names (masc.) a name (masc.)

�ن�ا �نا �ب �ن�ا �بtwo sons (masc.) a son (masc.)

�ن�ا �نتا �ب �نة�ا �بtwo daughters (masc.) a daughter (masc.)

� �ن�ا ؤا cم�ر � ؤ�ا cم�رtwo men (masc.) a man (masc.)

� �ن�ا م�رأتا � م�رأة�اtwo women (fem.) a woman (fem.)

Two (masc.) �ن�ا �نا �ث

Two (fem.) �ن�ا �نتا �ث

III. Particles

The connecting hamza(t) appears only in the definite article.

The ـ�ا ل

Writing of Letter 'alif (continued)

Consonant 'alif

Choosing Between the Forms at the Middle of the Word

All the different forms of hamza(t) at the middle and the end of words are pronounced the same way, which is a glottal stop. There is not any real reason for why the figures change so much. This is just one of the awkward aspects of Arabic.

Choosing between the different forms depend on the vowels before and after the hamza(t). To understand how the suitable form of hamza(t) is chosen, a simple principle must be introduced first, which is the "relative strength of different vowels."

The following figure demonstrates the relative strength of vowels. The vowels are arranged from the left to right respectively to their relative strength.

Strongest Weakest

Short I Short U Short A No Vowel (Stillness)

cرة �كس� ال cالض¦م¦ة cحة� �فت ال cو� ك الس¶cن

Short I is stronger than Short U. This one is stronger than Short A, and this is stronger than the stillness.

The stronger vowel before or after the hamza(t) will indicate its shape.

Example:

�ر� �ئ بA well (fem.)

Succeeding Vowel

The hamza(t) Preceding Vowel

Stillness ـئـ Short I

Short I is stronger than stillness. Therefore, the hamza(t) will be in the form

that suits the short I : . ـئـ

Suitable Form Stronger Vowel

ـئـ Short I

ـؤ Short U

ء / ـأ Short A

Stillness can never precede and follow a consonant at the same time (because still letters don't follow each others without separation), so there is not a form that suits that case.

More examples:

cؤر� بFoci

(sing. focus is fem.)

Succeeding Vowel

The hamza(t) Preceding Vowel

Short A ـؤ Short U

�ل ئ cس≈ (He/it) was asked

Succeeding Vowel

The hamza(t) Preceding Vowel

Short I ـئـ Short U

س�� فأ

An ax (fem.)

Succeeding Vowel

The hamza(t) Preceding Vowel

Stillness ـأ Short A

سأل(He) asked

Succeeding Vowel

The hamza(t) Preceding Vowel

Short A ـأ Short A

تو�أم�A twin

Succeeding Vowel

The hamza(t) Preceding Vowel

Short A ـأ Stillness

Long VowelsThe three long vowels in Arabic (aa, oo, ee) are not really discrete vowels; rather each one of these is composed of a short vowel (a, u, i) followed by the corresponding still consonants ( ' , w, y).

By understanding this, or more simply by just keeping in mind that the weak litters that denote long vowels are always still (i.e. not followed by any short

vowel), we can apply the same aforementioned rules to transcribe the hamza(t) that is followed or preceded by a long vowel.

Examples:

�ل� ؤا cسA question (masc.)

Succeeding Vowel

The hamza(t) Preceding Vowel

Short A ـؤ Short U

دؤcو�ب�persistent (masc. adjective)

Succeeding Vowel

The hamza(t) Preceding Vowel

Short U ـؤ Short A

�س� �ي رئ

A president (masc.)

Succeeding Vowel

The hamza(t) Preceding Vowel

Short I ـئـ Short A

هcدcو�ؤcهcم�(The) quietness (of) them

= their quietness (masc.)

Succeeding Vowel

The hamza(t) Preceding Vowel

Short U ـؤ Stillness

�ه�م� �هcدcو�ئ بBy (the) quietness (of) them

= by their quietness (masc.)

Succeeding Vowel

The hamza(t) Preceding Vowel

Short I ـئـ Stillness

� �ؤcنا ما(The) water (of) us

= our water (masc.)

Succeeding Vowel

The hamza(t) Preceding Vowel

Short U ـؤ Stillness

�ي� �ئ ر�دا(The) dress (of) me

= my dress (masc.)

Succeeding Vowel

The hamza(t) Preceding Vowel

Short I ـئـ Stillness

Special Cases

Case One

If the hamza(t) was preceded by a long vowel I (ee), it will take only the form

.no matter what vowel was following itـئـ

Example:

�ئة� �ي بAn environment (fem.)

Succeeding Vowel

The hamza(t) Preceding Vowel

Short A ـئـ Stillness

Note that in this case the hamza(t) should have been written ـأ because the Short A is the dominating "move" or short vowel. However, since that the hamza(t) is preceded by a long I (ee), the hamza(t) must be rendered in

the formـئـ .

Another example:

cو�ن �ئ جر�يBold (plu. masc. adj.)

Succeeding Vowel

The hamza(t) Preceding Vowel

Short U ـئـ Stillness

Case Two

If the hamza(t) was preceded by a long vowel A (aa) or a long vowel U (oo)

and followed by a short A (a), it will take the form ءinstead of ـأ .

Examples:

�ءة �ق�راA reading (fem.)

Succeeding Vowel

The hamza(t) Preceding Vowel

Short A ء Stillness

و�ءة� cرcمA magnanimity (fem.)

Succeeding Vowel

The hamza(t) Preceding Vowel

Short A ء Stillness

Writing of Letter 'alif (continued)

Consonant 'alif

Choosing Between the Forms at the End of the Word

Choosing between the different forms of hamza(t) at the end of the word is simpler than at the middle of the word. When we chose the correct form for hamza(t) at the middle of the word we looked at the vowel preceding and the vowel succeeding the hamza(t), compared their relative strength, then chose

the form that suits the stronger vowel. Here, we will practically do the same, but instead of comparing between the two vowels around the hamza(t), we will only occupy ourselves with the vowel preceding the hamza(t) but not the one following it.

Depending on which vowel precedes the hamza(t), we will choose one of the following forms:

Suitable Form Vowel

ـئ Short I

ـؤ Short U

ـأ Short A

ء Stillness

Examples:

�ر�ئ� قاA reader (masc.)

The hamza(t) Preceding Vowel

ـئ Short I

cؤ cيج�ر(He) dares

The hamza(t) Preceding Vowel

ـؤ Short U

قرأ(He) read (past)

The hamza(t) Preceding Vowel

ـأ Short A

ء� شي�A thing (masc.)

The hamza(t) Preceding Vowel

ء Stillness

ضو�ء�Light (masc.)

The hamza(t) Preceding Vowel

ء Stillness

�ء� ماWater (masc.)

The hamza(t) Preceding Vowel

ء Stillness

هcدcو�ء�Quietness (masc.)

The hamza(t) Preceding Vowel

ء Stillness

بر�ي�ء�Innocent (masc. adj.)

The hamza(t) Preceding Vowel

ء Stillness

Roots

In Indo-European languages such as English, the infinitive is usually the basic from of the verb of which the rest of the forms are derived.

For example, the infinitive "to talk" is the source of many derived words:

Talk Infinitive

Talking Present participle

Talked Past participle

Talk Present simple

Talked Past simple

Talk Noun

We see that the main stem of the infinitive stays preserved, while the inflection works by affixing other parts to the stem. At least it is so most of the time.

Unfortunately, in Semitic languages things are a little bit more complex than that.

In Arabic, the basic source of all the forms of a verb is called the "root" of the

verb الف�ع�ل� cجذ�ر .

The root is not a real word, rather it is a sequence of three consonants that can be found in all the words that are related to it.

Most roots are composed of three letters, very few are of four or five letters.

The root can be easily obtained from the 3rd person masculine singular past form (the perfective) of the verb.

Look at these roots:

Meaning of Verb Root 3rd person masc. sing. past (perfective) verb

(He) did F " L ل ع ف fa"al(a) فعل(He) wrote K T B ب ت katab(a) ك كتب

(He) studied D R S س ر daras(a) ددرس

(He) drew (a picture) R S M م س ر rasam(a)

رسم

(He) ate ' K L ل ك أ 'akal(a) أكل(He) knew " L M م ل ع "alim(a) �م عل

(He) was/became bigger K B R ر ب ك kabur(a) cر كب

(He) rolled (something) D H R J ج ر ح د dahraj(a)

ر دح�ج

You see that the root is not a word; it is just a sequence of consonants. The consonants of the root are separated by different vowels in different words. They can also be separated by other extra consonants that do not belong to the root.

The root is used to make all the forms of a verb. It is used to make nouns as well.

Each root pertains to a certain meaning, e.g. K T B ب ك ت pertains to

"writing."

See the following example:

MeaningWords derived from the root ت ك

ب

Verbs (he) wrote katab(a) كتب≈ (he) was/became written kutib(a) �ب cت ك(he) was/became written 'inkatab(a) �كتبان(he) made (somebody)

write kattab(a) ¦ب كت(he) made (somebody)

write 'aktab(a) �تبأ ك(he) exchanged writing with→ (he) corresponded with kaatab(a) تباك

(he) exchanged writing→ (he) corresponded

takaatab(a) تباكت

(he) wrote himself→ (he) subscribed 'iktatab(a) �ا تبتك(he) sought writing 'istaktab(a) ت �س� �تبا ك

Nouns

writing katb �ب كتwriting

→ book/dispatch kitaab �ت باكwriting kitaaba(t) �ت اك ةبbooklet kutayyib cت §بيك

writing (man)→ writer kaatib �باك تwritten

→ letter maktoob �تم بوكdesk/office maktab �تبم ك

library/bookstore maktaba(t) م �تب ةكphalanx kateeba(t) يكت ةب

So basically all these words were created by taking the root ب ت and ك

adding letters or vowels to it. This is how Semitic languages work.

Almost all Arabic words are structured on roots. Words in Arabic grammar belong to three categories:

Noun cم �س� .includes pronouns, adjectives and most adverbs : اال

Verb cف�ع�ل� .there are three main verbal structures in Arabic : ال

Letter (particle) cف �حر� .small words that do not have roots : ال

So small words without known roots were not even qualified enough to carry the title of a "word" in Arabic grammar. Many of these "letters" are prepositions and they do not undergo inflection.

The letters of the root are called the original letters of a word فcاألح�رc ¦ة �ي cاألص�ل .

The variable letters that appear between the root letters in different words are called the additional letters فcاألح�رc دة� cالزائ .

The letters that can serve as additional letters are ten: ا هـ تأ ن م ل س

ي وThese letters are rounded up in the word: � �ها �ي cمcو�ن �ت you asked me" = سأل

for/about it."

There are standard patterns for adding additional letters to the root. These

patterns are called 'awzaan ن� �أو�زا = "measures" or 'abniya(t) ية� �ن �أب = "structures."

For example:

'infa"al(a) �ن �فعلا fa"al(a) فعل(he/it) did himself/itself (he/it) did

'inkasar(a) �ن �كسرا kasar(a) broke himself/itself (he/it)كسر (he/it) broke

'insabb(a)�ن �صب¦ا

sabb(a)

poured (he/it)صب¦himself/itself

(he/it) poured

So this structure 'in*a*a*(a) has a specific sense that is different from

the basic structure *a*a*(a).

Both structures are structures of active voice past (perfective) verbs. However, there is a difference between the two that is reminiscent of the Latin or French difference between faire and se faire. The 'in*a*a*(a) structure is called a "reflexive" verb because it denotes a self-directed action.

You can put so many root letters in place of the stars and you will get the same outcome.

Usually stars are not used but instead the root ل ع do" is used for" = ف

giving prototypes of different structures.

So these two structures will be standardized:

(He/it) did fa"al(a) فعل(He/it) did himself/itself 'infa"al(a) � �ن فعلا

Etymology Note: Biliteral Roots

Arabic grammar recognizes three-letter, four-letter, and five-letter-roots, but not anything more or less than that. Five-letter-roots exist only in nouns but not verbs.

However, there are several Arabic nouns that have only two consonants in them, for example:

Father 'ab أبBrother 'akh أخ

Son 'ibn �نا �ب

Name 'ism �س�ماMouth fam فمHand yad يدBlood dam دم

The ا is not an original letter but is only a "liaison" that is added in front of some words for a phonological reason. More about this is available on this page and this one.

Classical Arabic grammarians did not recognize biliteral roots and considered them all to be modified from triliteral roots. For example, grammarians of the

classical period (8th & 9th centuries) debated whether the root of س�ما� was

و م م or س س . و

However, the truth is that Arabic indeed has biliteral roots. Moreover, there was a time at which Arabic did not have any roots but biliteral roots.

This can be shown by comparing the meanings of different triliteral roots; for example:

Proto-Root ط ق(He) cut qata"(a) عقط

(He) cut qatal(a) لقط(He) cut qat t (a) ¦طق

(He) stitchedoriginal sense:

(He) cutqatab(a) بقط

(He) picked (a plant part) qataf(a) فقط

(He) took a bite qatam(a) مقط(He) dripped qatar(a) رقط

Notice that all these triliteral roots have a common general meaning, and they all share the first and second root-letters. This indicates that all these roots

were derived from a common biliteral ancestor, which is the proto-root ط . ق

Surprisingly, this is also the root of the English verb "cut!" In fact, this has to do with more than mere chance. Such basic verbs are often related to the sound that an action produces, so it is not unusual that they be similar in totally unrelated languages.

Knowing this idea of proto-roots will be very helpful in determining the original meanings of a large number of roots.

For example, knowing that there was a proto-root ط whose meaning was قrelated to cutting and to "pieces" will help us figure out easily the original meaning of the following root:

قطنqatan(a)

(he) dwelled

This verb has an odd meaning compared to the meaning of the proto-root ق However, there is another word of the same root whose meaning seems . طmore original:

قcط�نqutn

cotton (masc.)

The English word "cotton" was borrowed from Arabic in Middle Ages. The meaning of "cotton" is more consistent with the general meaning of the proto-

root, so we can easily infer that the verb qatan(a) has an altered meaning

and that the original meaning of the root ن ط ".is related to "pieces ق

Hebrew has the same root:

נ ט' ק(qaaton

(He) became small(er)

Another interesting point is that there are several roots that were derived from the same proto-root but they look somewhat different these days. For example:

(He) killed qatal(a) لقت(He) was parsimonious qatar(a) رقت

Bowel qitb � بق�تDust

→ darkness qataam �ماقت

Kind of a thorny plant qataad �داقت

These words have the proto-root ت ط which is very similar to , ق and , ق

they probably were one thing initially. Because we know the meaning of ط ق, we can easily determine the original meaning of ت .("pieces") ق

Knowing these principles will help us figure out the original meanings of countless vague roots, and it will help us avoid making mistakes like, for

example, saying that the original meaning of the Arabic root ف ر is "to ع

know." This is clearly false as the proto-root ف has a totally different رmeaning.

Proto-Root ف ر

(He) made deviate haraf(a) رفح(He) swept away, carried

along jaraf(a) رفج

(He) shed (tears) tharaf(a) رفذoriginal sense:

(He) moved fast zaraf(a) رفز(He) blinked (eye)

original sense:(He) moved fast

taraf(a) رفط(He) was/became

extravagant tarif(a) ر�فتoriginal sense:

(He) transgressed qaraf(a) رفق(He) was/became funny

original sense:(He) was nifty

zaruf(a) رcفظSo it is clear that the proto-root ف had a meaning that is related to ر"moving," "flowing," or "straightness."

As for the root ف ر : ع

عرف

"araf(a)

(he) knew, became acquainted with(used for "being familiar with people, things, etc.," equivalent to the French connaître )

This verb is irregular both in meaning and structure, as it is shown in the verb section.

However, another word from the same root is:

عcر�ف"urf

comb, crest (of rooster)This word is clearly related to the original meaning of the root ("moving,"

"flowing," or "straightness"). Thus, the original meaning of ف ر is not "to عknow."

The proto-root ف was originally ف is an interesting one. The Arabic letter رa P like the English P, so it is not surprising that roots derived from the proto-

root ب ف have similar meanings to the ones derived from ر . ر

For example:

Proto-Root ب رoriginal sense:

(He) flowed sarab(a) ربس

(He) soaked (intr.) sharab(a) ربش

(He) escaped harab(a) ربه

(He) approached qarib(a) ر�بقoriginal sense:(He) departed rarab(a) ربغ

(He) leaked, flowedModern North Syrian Arabic,

borrowed from Aramaiczarab(a) ربز

original sense:(He) became improper tharib(a) ر�بذ

(He) became ruined kharib(a) ر�بخoriginal sense:

(He) became improper warib(a) ر�بو

Road darb ر�بدAll these words, and others, are related to the same meaning which is "moving," "flowing," or "straightness."

So now that we have an understanding of the original meanings of ف ر & ر we can try to answer some famous questions, like the etymology of the , ب

word "Arab" عرب�.

A German man once said that the word "arab originally meant "arid land." This became so popular that it was taught at schools in some Arab countries; but when taking the meaning of the proto-root in consideration, this meaning appears unconvincing.

Another, better, theory said that this word was altered from "abar عبر, which is related to "passing" or "traversing." This root is also the root of the word "Hebrew," and they are all related to the nomadic lifestyles of those peoples.

However, by comparing many roots derived from the proto-roots ر ب &ف it appears clearly that the original meanings of these roots were related to ,ر

"filling" and "earth" not to "moving." So the truth is that the word "abar is

modified from "arab not the other way around.

Thus, the word "Arab" originally meant a "wanderer" or a "nomad." The roots

ب ر عand ب ر .carry related meanings in several Semitic languages غ

"Pieces"

Q T ت ق

Q T ط ق

Q S س ق

Q S ص ق

Q D ض ق

K T ت ك

K S س ك

"Moving"

R B ب رR F ف ر

Quadriliteral Roots

Triliteral roots were created by adding a third letter to a biliteral roots. Quadriliteral roots were mostly created by doubling a biliteral root, and sometimes by adding a fourth letter to a triliteral root.

Many examples exist on this page. We will mention here only two examples based on the proto-roots we talked about above:

Proto-Root ط ق

(He) dripped qat q at(a) � قطقط

Proto-Root ف ر

(He) flapped, fluttered rafraf(a) رفرف

Quadriliteral and Pentaliteral roots were often extracted from foreign loanwords.

Example,

A traditional Arab currency is the dirham, which is still a currency unit in several Arab countries today. A dirham was a silver coin in old times. The name of the dirham comes from the Greek drachmē or drachma. It was

Arabized to follow the standard Arabic noun structure fi"lal ف�ع�لل� .

drachmē → dirham هم د�ر�

Some triliteral roots were also extracted from foreign loanwords. An

interesting example is the word siraat �ط� meaning "a way" or "a ص�راpath." This word comes from the Latin strata = "paved road." The Latin word

was rendered into the standard verbal noun structure fi"aal ل�اف�ع� . This is

the same structure as that of the word kitaab �ت �ك ب�ا = "a book" or "a dispatch."

strata → siraat �طاص�ر

NounsAs we have mentioned, Arabic words are three types:

Nouns

Verbs

Particles

We are going to begin by talking about the first branch, the nouns. A noun (or a substantive) (Arabic: م� �س� a name") is a name or an" = ا

attribute of a person (Ali), place (Mecca), thing (house), or quality (honor). The word "noun" comes from the Latin nomen = "name." The noun or substantive category in Arabic includes in addition to simple nouns the pronouns, adjectives, adverbs, and verbids (participles and verbal nouns).

Nouns that designate material things (Ali, Mecca, house) are called concrete nouns. Nouns that designate immaterial things (honor) are called abstract nouns.

Permanent names of persons or places are called proper nouns cء� ما أس�² �سother nouns are called common nouns ² ,علم ج�ن cء� ما Proper nouns .أس�refer to unique or particular objects (cannot be preceded by words such as "some" or "any"); common nouns refer to non-unique or non-particular objects (can be preceded by words such as "some" or "any").

Common nouns are several types in Arabic:

►Count nouns are nouns that refer to single units when they are grammatically singular, and to plural units when they grammatically plural.

Examples:

Plural Count Nouns Singular Count Nouns

rijaal

�لار�جrajul

رجcلmen man

buyoot

c cي �توبbayt

�ت بيhouses house

kutub

cتcب كkitaab

�ت �باكbooks book

►Mass nouns are nouns that refer to single as well as plural units when they are grammatically singular, and to plural units when they are grammatically plural. These usually refer to plants or animals.

Examples:

Plural Mass Nouns Singular Mass Nouns

thimaar�م �راث

thamarثمر

fruits fruit/fruits

'ashjaarجأ �راش�

shajarشجر

trees tree/trees

tuyoor

c �روطcيtayr

�ر birdsطي bird/birds

When mass nouns refer to uncountable objects (such as water, sugar. etc.), the grammatically singular noun will refer to small or large amounts of the object, and the grammatically plural noun will refer to large amounts of the object.

Examples:

Plural Mass Nouns Singular Mass Nouns

miyaah

� هام�يmaa'<

�ء large amount ofماwater

small/large amount of water

dimaa'<�د�م ءا

dam large amount ofدم

bloodsmall/large amount of

blood

riyaah riyh

�حار�ي �ح ر�يlarge amount of

windsmall/large amount of

wind

Some nouns, like the names of materials, can indicate either a unit (a piece, a type) or a substance, so those can be both countable and uncountable. However, when plural, they usually refer only to multiple units (countable only).

Examples:

Plural Count Nouns Singular Mass Nouns

'awraaq

�و�رأ قاwaraq

ورقpapers

paper/papersor

small/large amount of paper

'akhshaab أ�خ�ش ا

ب

khashab

خشpieces of woodب

types of wood

piece/pieces of woodtype/types of wood

orsmall/large amount of

wood

zuyoot

c ي cتوز�zayt

زي�تtypes of oil

type/types of oilor

small/large amount of oil

►Collective nouns or irregular (broken) plural nouns are grammatically singular nouns that refer to plural units or to large amounts of uncountable objects. All the "plural" nouns listed in the above examples belong to this

category; I am calling them "plural" to avoid causing confusion and because this is how they are usually called.

Oddly enough, although these nouns are called irregular plurals they are in fact singulare tantum, which means that they do not have grammatically plural forms.

It is possible for irregular plural nouns that refer to humans to be treated grammatically as plural nouns; this is typical of Modern Standard Arabic.

DeclensionNouns and verbs undergo inflection ف� which means that parts of , تصر¶them change in order to express changes in gender, number, case, tense, voice, person, or mood. The inflection of nouns is called declension, and the inflection of verbs is called conjugation. The declension of Arabic nouns expresses changes in:

Gender— Arabic nouns have two grammatical genders.

Number— Arabic nouns have three grammatical numbers.

Case— Arabic nouns have three grammatical cases.

State— Arabic nouns have three grammatical states.

GenderThe two genders in Arabic are the masculine and feminine. Every Noun in

Arabic is either masculine or feminine— there is no neuter gender in Arabic. Each object and animal is either masculine or feminine.

Thus, nouns are four categories in Arabic:

True masculine: nouns that refer to male humans or animals. Figurative masculine: masculine nouns that refer to objects.

True feminine: nouns that refer to female humans or animals. Figurative feminine: feminine nouns that refer to objects.

►Gender MarkersThe are feminine markers for nouns but no masculine markers. The feminine

markers are three affixes (-a(t), -aa'<, and -aa), all apparently

originating from one ancestor that was something like -at or -t and which performed a dual augmentative-diminutive function rather than signifying the feminine gender. Relatively few count and mass nouns are feminine without having feminine markers. However, all collective nouns (irregular (broken) plurals) are feminine without having feminine markers.

NumberThe grammatical numbers in Arabic are:

Singular: nouns that refer to one person or thing. Dual: nouns that refer to two persons or things. Plural: nouns that refer to more than two persons or things.

►Number MarkersThe number markers are suffixes positioned following the feminine gender marker (if one existed).

stem(-feminine marker)-number marker

The number markers are composed of two parts, a first part that is inflected for case, and a second part that is inflected for state.

number marker = case marker-state marker The basic nominative-absolute marker for singular nouns, including collective

nouns (irregular (broken) plurals), is -un. This marker is inflected for three cases (has three forms for three cases) and two states (has two forms for two states) thus yielding a total of six possible combinations, all of which are

singular markers (-un,-an,-in,

-u,-a,-i).

The nominative-absolute marker for dual nouns is -aani. This marker is inflected for two cases (has two forms for two cases) and two states (has two forms for two states) thus yielding a total of four possible combinations, all of which are dual markers

(-aani,-ayni,-aa,-ay).

The nominative-absolute marker for masculine plural nouns is -oona and

for feminine plural nouns is -aatun. These two markers are inflected for two cases and two states like the dual marker, and each have four possible forms

(-oona,-eena,

-oo,-ee) (-aatun,-aatin,-aatu,-aati). When adding the feminine

plural marker to nouns with a feminine gender marker -a(t), the -a(t) is removed.

CaseNouns in formal Arabic have three grammatical cases:

Raf" (Nominative): case of nouns functioning as the subject of a sentence.

Nasb (Accusative/Dative/Vocative): a case with a myriad of uses (about ten uses); most importantly, it is the case of nouns functioning as objects.

Jarr (Genitive/Ablative): a case that indicates possession or being object of a preposition.

►Case MarkersThe case markers are the case-inflected parts of the number markers. They are the first parts of the number markers and the state markers are the second parts.

stem(-feminine marker)-case marker