Applied Anatomy of the Sacral Plexus

-

Upload

timothy-umukoro -

Category

Documents

-

view

58 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Applied Anatomy of the Sacral Plexus

1

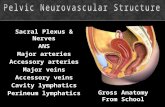

INTRODUCTION

In human anatomy, the sacral plexus is a nerve plexus which provides motor and

sensory nerves for the posterior thigh, most of the lower leg, the entire foot, and

part of the pelvis. It is part of the lumbosacral plexus and emerges from the sacral

vertebrae.

The sacral plexus lies in the inner surface in the posterior pelvic wall anterior to

piriformis, posterior to the internal iliac vessels and ureter, and behind the

sigmoid colon on the left. The superior gluteal vessels run either between the

lumbosacral trunk and first sacral ventral ramus or between the first and second

sacral rami, while the inferior gluteal vessels lie between either the first and

second or second and third sacral rami. Its nerves supply the lower limbs, its

major product being the sciatic nerve. (Thieme Atlas of Anatomy, 2006 et al)

All the nerve roots entering the plexus split into anterior and posterior divisions,

and the nerves arising from these are as follows (see fig.1 below):

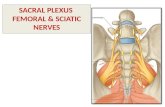

Composition

It is formed by the union of the fourth lumbar ventral ramus with all of the fifth

lumbar ventral ramus to form a lumbosacral trunk and by the union of this trunk

with the first to third sacral ventral rami and part of the fourth sacral ventral

ramus (the remainder of the fourth sacral ramus joins the coccygeal plexus)

[fig.1&2].

2

Fig. 1 Full schematics of the sacral plexus, showing the divisions and insertions

3

Fig2. Labeled sketch of the composition of the sacral plexus

The nerves forming the sacral plexus converge toward the lower part of the

greater sciatic foramen, and unite to form a flattened band, from the anterior and

posterior surfaces of which several branches arise.

The band itself is continued as the sciatic nerve, which splits on the back of the

thigh into the tibial nerve and common fibular nerve; these two nerves

sometimes arise separately from the plexus, and in all cases their independence

can be shown by dissection.

Often, the sacral plexus and the lumbar plexus are considered to be one large

nerve plexus, the lumbosacral plexus. The lumbosacral trunk connects the two

plexuses.

RELATIONS

The sacral plexus lies on the back of the pelvis between the piriformis muscle and

the pelvic fascia. In front of it are the internal iliac artery, internal iliac vein, the

4

ureter, and the sigmoid colon. The superior gluteal artery and vein run between

the lumbosacral trunk and the first sacral nerve, and the inferior gluteal artery

and vein between the second and third sacral nerves.

(Thieme Atlas of Anatomy, 2006 et al)

Fig.3 Sacral plexus. Sagittal view, showing its relations.

5

BRANCES OF SACRAL PLEXUS

All the nerves entering the plexus, with the exception of the third sacral, split into

ventral and dorsal divisions, and the nerves arising from these are as follows of

the table below:

6

(Drake et al: Gray’s Anatomy for students www.studentconsult.com)

Nerve to the Quadratus Femoris and Gemellus Inferior

The nerve to the quadratus femoris and gemellus inferior arises from the anterior

divisions of the fourth and fifth lumbar and first sacral nerve roots. It leaves the

pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen, below the piriformis, and runs down in

front of the sciatic nerve, the gemelli, and the tendon of the obturator internus,

then enters the anterior surfaces of the quadratus femoris and gemellus inferior

muscles. This nerve gives an articular branch to the hip joint.

Nerve to the Obturator Internus and Gemellus Superior

7

The nerve to the obturator internus and gemellus superior arises from the

anterior division of the fifth lumbar and first and second sacral nerve roots. It

leaves the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen below the piriformis and

gives off the branch to the gemellus superior, entering the upper part of the

posterior surface of this muscle. This nerve then crosses the ischial spine, enters

the perineum through the lesser sciatic foramen, and pierces the pelvic surface of

the obturator internus muscle.

Nerve to the Piriformis

The nerve to the piriformis arises from the posterior divisions of the first and

second sacral nerve roots and enters the anterior surface of the muscle.

Fig 4. Diagram of sacral plexus landmarks.

8

Superior and Inferior Gluteal Nerves

The superior gluteal nerve arises from the posterior divisions of the fourth and

fifth lumbar and first sacral nerve roots. It leaves the pelvis through the greater

sciatic foramen above the piriformis, accompanied by the superior gluteal vessels,

and divides into a superior and an inferior branch. The superior branch

accompanies the upper branch of the deep division of the superior gluteal artery

and ends in the gluteus minimus. The inferior division gives filaments to the

gluteus medius and minimus and ends in the tensor fascia lata.

The inferior gluteal nerve arises from the posterior divisions of the fifth lumbar

and first and second sacral nerve roots. It leaves the pelvis through the greater

sciatic foramen, below the piriformis, and divides into

branches that enter the deep surface of the gluteus maximus.

Posterior femoral cutaneous nerve

The posterior femoral cutaneous nerve is distributed to the

skin of the perineum and posterior surface of the lower

portion of the buttock, thigh, and leg (see the following

image). It arises partly from the posterior divisions of the first

and second sacral nerve roots and from the anterior divisions

of the second and third sacral nerve roots.

The posterior femoral cutaneous nerve continues from the

pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen below the

piriformis; it then descends beneath the gluteus maximus

with the inferior gluteal artery and runs down the back of the

thigh beneath the fascia lata and over the long head of the

9

biceps femoris to the back of the knee. Here, it pierces the deep fascia and

accompanies the small saphenous vein to about the middle of the back of the leg,

with its terminal twigs communicating with the sural nerve. Its branches are all

cutaneous and are distributed to the gluteal region, the perineum, and the back

of the thigh and leg, as follows:

Inferior cluneal branches turn upward around the lower border of the gluteus

maximus and supply the skin covering the lower and lateral part of that muscle

Perineal braches curve forward below and in front of the ischial tuberosity, pierce

the fascia lata, and run forward beneath the superficial fascia of the perineum to

the skin of the scrotum in the male and of the labium majus in the female. (Drake

et al: Gray’s Anatomy for students www.studentconsult.com)

Pudendal Nerve

It arises from sacral plexus in the pelvis from spinal nerves S2, S3, S4. In the

posterior part of the pudendal canal the pudendal nerve gives off inferior rectal

nerve and then it divides into to terminal branches - (a) perennial nerve and (b)

dorsal nerve of penis.The inferior rectal nerve pierces the medial wall of pudendal

canal, crosses the Ischiorectal fossa from lateral to medial side and supplies the

external sphincter, the skin around the anus and the wall of the anal canal below

the pectinate line. (Dr.Barin Bose MS et al)

10

Fig. 5 Sketch of pudendal nerve sacral origin and its branches.

Sciatic Nerve

The sciatic supplies nearly the whole of the skin of the leg, the muscles of the

back of the thigh, and those of the leg and foot. It is the largest nerve in the body,

measuring 2 cm in breadth, and is also the continuation of the flattened back of

the sacral plexus. The sciatic nerve passes out of the pelvis through the greater

sciatic foramen, below the piriformis muscle. It descends between the greater

trochanter of the femur and the tuberosity of the ischium and along the back of

the thigh to about its lower third, where it divides into 2 large branches, the tibial

and common fibular (peroneal) nerves. This division may take place at any point

between the sacral plexus and the lower third of the thigh.

The sciatic nerve supplies the hamstring muscles and all of the muscles and skin of

the leg and foot via its 2 branches, the tibial and common fibular nerves.

Tibial Nerve

The tibial nerve is the larger of the 2 terminal branches of the sciatic nerve. It

arises from the anterior branches of the fourth and fifth lumbar and first, second,

and third sacral nerve roots. This nerve descends along the back of the thigh and

through the middle of the popliteal fossa to the lower part of the popliteus

muscle, where it passes with the popliteal artery beneath the arch of the soleus.

11

The tibial nerve then runs along the back of the leg with the posterior tibial

vessels to the interval between the medial malleolus and the heel, where it

divides beneath the flexor retinaculum (laciniate ligament) into the medial and

lateral plantar nerves.

APPLIED ANATOMY OF THE SACRAL PLEXUS

The sacral region can develop problems in several ways, including injury, tumor

spread, or malignant infiltration. Regardless of the cause, injuries to the sacral

plexus exhibit similar symptoms. An injury to the sacral plexus is suspected when

the affected body parts are all confined to the area serviced by the sacral plexus.

A complete or partial injury to the sacral plexus, therefore, leaves the patient with

a deficit in the sensation and/or movement in the lower limb supplied by the

corresponding nerve(s) affected. Patients may also experience neuropathic pain

in the distribution of the affected nerve(s).

In both situations, the nerve loses the capacity to effectively transmit electrical

signals to the muscles. This situation may persist for days, weeks, and sometimes

months. If a compression force is released from the nerve, the recovery is full.

When compression persists, recovery may not occur or may be suboptimal or

cause residual neuropathic pain.

The sacral plexus is not commonly involved in malignant tumours of the pelvis

because it lies behind the relatively dense presacral fascia, which resists all but

locally very advanced malignant infilteration. Most lumbosacral plexopathies due

to trauma are from very violent injuries, such as automobile-pedestrian accidents,

high-speed car accidents, or falls from heights, and are often associated with

12

damage to internal organs, blood vessels, and bony structures, especially the

pelvic ring. When it occurs, there is intractable pain in the distribution of the

branches of the plexus which may be very difficult to treat.

(Gray’s Anatomy, 40th edition et al)

Mechanical Low Back Pain

Mechanical low back pain (LBP) remains the second most common symptom-

related reason for seeing a physician in the United States. Of the US population,

85% will experience an episode of mechanical LBP at some point during their

lifetime. Fortunately, the LBP resolves for the vast majority within 2-4 weeks.

(Everett C Hills, MD, MS; Chief Editor: Rene Cailliet, MD et al)

Patients generally present with a history of an inciting event that produced

immediate low back pain (LBP). The most commonly reported histories include

the following:

Lifting and/or twisting while holding a heavy object (eg, box, child, nursing

home resident, a package on a conveyor)

Operating a machine that vibrates

Prolonged sitting (eg, long-distance truck driving, police patrolling)

Involvement in a motor vehicle collision

Falls

Pathophysiology

Causes of mechanical low back pain (LBP) generally are attributed to an acute

traumatic event, but they may also include cumulative trauma as an etiology. The

severity of an acute traumatic event varies widely, from twisting one’s back to

being involved in a motor vehicle collision. Mechanical LBP due to cumulative

trauma tends to occur more commonly in the workplace.

13

In a systematic study review, Chen et al investigated whether a sedentary lifestyle

(which the authors defined as including sitting for prolonged periods at work and

during leisure time) is a risk factor for LBP. Examining journal articles published

between 1998 and 2006, they identified 8 high-quality reports (6 prospective

cohort and 2 case-control studies). While 1 of the cohort studies reported a link

between sitting at work and the development of LBP, the other investigations did

not find a significant connection between a sedentary lifestyle and LBP. Chen and

coauthors concluded that a sedentary lifestyle alone does not lead to LBP.

In a birth cohort study from 1980-2008, Rivinoja et al investigated whether

lifestyle factors, such as smoking, being overweight or obese, and participating in

sports, at age 14 years would predict hospitalizations in adulthood for LBP and

sciatica. The authors found that 119 females and 254 males had been hospitalized

at least once because of LBP or sciatica. Females who were overweight had an

increased risk of second-time hospitalization and surgery. Smoking in males was

linked with an increased risk of first-time nonsurgical hospitalization and second-

time hospitalization for surgical treatment. Herniation of the nucleus pulposus

oculd also lead to mechanical middle and low back pain;

HERNIATION OF THE NUCLEUS PULPOSUS

The intervertebral disc is the largest avascular structure in the body. It arises from

notochordal cells between the cartilaginous endplates, which regress from about

50% of the disc space at birth to about 5% in the adult, with chondrocytes

replacing the notochordal cells. Intervertebral discs are located in the spinal

column between successive

vertebral bodies and are oval in

cross section.

The disc's annular structure is

composed of an outer annulus

fibrosus, which is a constraining ring

that is composed primarily of type 1

collagen. The intervertebral disc has

Fig 6. Sketch showing

Herniation

14

the ability to rotate or bend without a significant change in volume and, thus,

does not affect the hydrostatic pressure of the inner portion of the disc, the

nucleus pulposus. The nucleus pulposus consists predominantly of type II

collagen, proteoglycan, and hyaluronan long chains, which have regions with

highly hydrophilic, branching side chains. (Everett C Hills, MD, MS; Chief Editor:

Rene Cailliet, MD et al)

Herniation or protrusion of the gelatinous pulposus into or through the anulus

fibrosus is a well recognized cause of low back pain (LBP) and lover limb pain.

Flexion of the vertebral column produces compression anteriorly and stretching

or tension posteriorly, squeezing the nucleus pulposus further posteriorly towards

the thinnest part of the annulus fibrosus. If the annulus fibrosus has degenerated,

the nucleus pulposus may herniate into the vertebral canal and compress the

spinal cord or the nerve roots of the caudal equina. This may lead to the

following;

Lumbago, an acute middle and low back pain may be caused by mild

posterolateral protrusion of the lumbar intevertebratal (IV) disc at the L5-

S1 level that affects nociceptive (pain) endings in the region, such as those

associated with posterior longitudinal ligaments. The clinical picture varies

considerably, but pain of acute onset in the lower back is a common

presenting symptom. Because muscle spasm is associated with low back

pain, the lumbar region of the vertebral column becomes tense and

increasingly cramped, causing painful movement. With treatment, the

lumbago type of back pain begins to fade after a few days; however, it may

gradually be replaced by sciatica.

Sciatica, pain in the lower back and hip radiating down the back of the

thigh into the leg, is often caused by a herniated lumbar IV discs that

compresses and compromises the L5 or S1 components of the sciatic nerve.

The IV foramina in the lumbar region decrease in size and the lumbar nerve

increases in size, which may explain why sciatica is so common. The general

rule is that when an IV disc protrudes, it usually compresses the nerve root

numbered one inferior to the disc; for example, the L5 nerve is compressed

by an L4-L5 IV disc herniation.( Moore and Dalley et al, 2006)

15

ANESTHESIA FOR CHILDBIRTH

Several options are available to women to reduce the pain and discomfort

experienced during childbirth. General anesthesia has advantages for emergency

procedures and for women who choose it over local anesthesia. General

anesthesia renders the mother unconscious; she’s unaware of the labour and

delivery.

Women, who choose local anesthesia such as a spinal, pudendal nerve, often

wish to participate actively and be conscious of their uterine contractions to bear

down or to push, yet do not wish to experience all the pain of labour.

A pudendal nerve block is a peripheral nerve block that provides local anesthesia

over the S2-S4 dematomes (the majority of the perineum) and the inferior

quarter of the vagina. It does not block the pain from the superior birth canal

(uterine cervics and superior vagina), so the mother is able to feel uterine

contractions. It can be re-administered, but to do so may be disaruptive and

involves the use of a sharp instrument in close proximity to the infant head.

(Moore and Dalley et al)

INJURY TO THE SUPERIOR GLUTEAL NERVE

This results in a characteristic motor loss, resulting in a disabling gluteus medius

limb, to compensate for weakened abduction of the thigh by the gluteus medius

and minimus. When a person is asked to stand on one leg, the gluteus medius and

minimus normally contracts as soon as the contralateral foot leaves the floor,

preventing tipping of the pelvis tot her unsupported side. When a person who has

suffered this lesion is asked to stand on one leg, the pelvis on the unsupported

side descends, indicating that the gluteus medius and minimus on the supported

16

side are weak or non-functional. This observation is referred to as a positive

trendelembung test. (Moore and Dalley et al)

INJURY TO THE SCIATIC NERVE

A pain in the buttock may result from the compression of the sciatic nerve by the

piriformis muscle (piriformis syndrome). Individuals involved in sports that

require excess use of the gluteal muscles (e.g Ice-skaters, cyclists, rock climbers)

and women are more likely to develop this syndrome. Complete section of the

sciatic nerve is uncommon. When this occurs, the leg is useless because extension

of the hip is impaired, as is flexion of the leg. All ankle and foot movement are

also lost. Incomplete section of the sciatic nerve may also involve the inferior

gluteal and/the posterior femoral cutaneous nerve. Recovery from a sciatic is

slow and incomplete.

With respect to the sciatic nerve, the buttock has a side of safety (its lateral side)

and a side of danger (medial side). Wounds or surgeries at the medial side of the

buttock are liable to injure the sciatic nerve and its branches to the harmstrings

(semitendinosus, semimembranosus and biceps femoris) on the posterior aspect

of the thigh. (Moore and Dalley et al)

INJURY TO THE TIBIAL NERVE

Injury to the tibial nerve is uncommon because of its deep and protected position

in the popliteal fossa; however, the nerve may be injured by deep lacerations in

the popliteal fossa. Posterior dislocation of the knee joint may also damage the

tibial nerve. Severance of the tibial nerve produces paralysis of the flexor muscle

in the leg and in the intrinsic muscles in the sole of the foot. People with a tibial

nerve injury are unable to plantarflex their ankle or flex their toes. Loss of

sensation also occurs on the sole of the foot. (Moore and Dalley et al)

17

Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome

Tarsal tunnel syndrome is a condition that is caused by compression of the tibial

nerve or its associated branches as the nerve passes underneath the flexor

retinaculum at the level of the ankle or distally. The tarsal canal is formed by the

flexor retinaculum, which extends posteriorly and distally to the medial malleolus.

The posterior tibial nerve lies between the posterior tibial muscle and the flexor

digitorum longus muscle in the proximal region of the leg and then passes

between the flexor digitorum longus and flexor hallucis longus muscle in the distal

region of the leg. The tibial nerve passes behind the medial malleolus and through

the tarsal tunnel and then bifurcates into cutaneous, articular, and vascular

branches. The main divisions of the posterior tibial nerve include the calcaneal,

medial plantar, and lateral plantar nerve branches. The medial plantar nerve

passes superior to the abductor hallucis and flexor hallucis longus muscles and

later divides into the 3 medial common digital nerves of the foot and the medial

plantar cutaneous nerve of the hallux. The lateral plantar nerve travels directly

through the belly of the abductor hallucis muscle, where it later subdivides into

branches. (Rajesh R Yadav, MD; Chief Editor: Robert H Meier et al)

PIRIFORMIS MUSCLE SYNDROME (PMS)

PM is a key to the lower extremity. Association of the PM with sciatic and other

nerves in the gluteal area make PMS a very frequent pathological condition. As a

matter of fact every abnormality on the lower extremity starting from the thigh

down to the foot (from active trigger points in hamstring muscles to Plantar

Fasciitis) may be directly connected to PMS (Novakovic et al).

The tension in the PM may affect following structures;

Sacral Plexus

18

In the place of origin (anterior surface of the sacrum and SI joint) the PM forms a

cushion for the sacral plexus especially to S2-S3 spinal nerve roots (Russell et al.,

2008). This plexus is the origin of many nerves (i.e., sciatic, gluteal inferior,

cutaneous posterior, etc.) which innervate the pelvic inner organs, the gluteal

area, and the lower extremities.

Fig 7. Diagram of the sacral plexus, stressing the importance of the piriformis muscle.

If the PM gets tense the sacral plexus doesn't have soft support anymore and

symptoms of irritation of the sacral plexus may develop. The patient will exhibit a

great variety of the clinical signs and symptoms because the sacral plexus is the

19

origin of the majority of peripheral nerves, which supply the pelvis and both lower

extremities.

The clinical signs of the irritation of the sacral plexus by the PM is a unique

combination of the lower back pain, peripheral symptoms in the lower extremity

and variety of visceral symptoms (e.g. constipation, intense menstrual pains,

erectile dysfunction, etc.).

Sciatic Nerve

PMS is the major cause of Sciatic Nerve Neuralgia (SNN). The sciatic nerve is

composed of two nerves: the tibial nerve (the anterior portion of the L4-S3 spinal

nerves) and the common peroneal nerve (the posterior portion of the L4-S2 spinal

nerves).

The sciatic nerve has several variants in its position in regard to the PM. Beaton

and Anson (1938) in their classical study examined 2250 cadavers and found that

sciatic nerve has the following major pathways in regard to the PM.

1. In 85% of the population the sciatic nerve has the most common route when

entire nerve exits the pelvis via the infrapiriformis recess, i.e. it is located below

the PM (see Fig. 8 'a').

2. In 10% of the population the tibial portion of the sciatic nerve passes below the

PM while the common peroneal portion of the sciatic nerve penetrates the PM

(see Fig. 8 'b').

3. In 2-3% of the population the tibial portion of the sciatic nerve passes below

the PM while the common peroneal portion of the sciatic nerve passes above the

PM (see Fig. 8 'c').

4. In 1% of the population both portions of the sciatic nerve penetrate the PM

(see Fig. 8 'd').

5. 1-2% of the population exhibit less frequently occurred pathways

20

Fig. 8. Sciatic nerve and PM

The common peroneal portion of the sciatic nerve is more frequently in trouble.

This is why patients with PMS are more likely to develop sensory and motor

abnormalities within the distribution of the common peroneal nerve (Lee and

Tsai, 1974; Limansky, 1988). However, both portions or only the tibial nerve

portion can be entrapped as well. For those patients, the clinical picture of Sciatic

Nerve Neuralgia is much more intense and they struggle with constant flare ups

during their entire life.

21

Gluteal Nerves and Arteries

The superior gluteal nerve and artery exit the pelvis via the suprapiriformis recess.

The inferior gluteal nerve and artery exit the pelvis via the infrapiriformis recess.

The superior gluteal nerve innervates gluteus medius, gluteus minimus and tensor

fascia latae muscles.

The inferior gluteal nerve innervates the gluteus maximus muscle.

Clinical importance: irritation of the gluteal nerves is accompanied by the

formation of the active trigger points, protective muscle tension and weakness in

the gluteal muscles.

The clinical sign of the inferior gluteal nerve neuralgia is weakness or complete

inability (in cases of complete palsy) to get up from the seated position.

The clinical sign of the superior gluteal nerve neuralgia is an unusual rolling gait.

Every time one raises foot on the unaffected side to make a step the half of the

pelvis on the affected side slightly goes downward instead of being on the same

level. The rolling gait is especially visible if the examiner gets on one knee to bring

his or her eyes to the level of the patient's pelvis and asks the patient to walk

slowly while observing the gait from the back and comparing both sides.

Pudendal Nerve and Artery

The pudental nerve is a major source of innervation of the sexual organs in males

and females. It innervates penis, scrotum, clitoris, labia as well as anal sphincter

and urethral sphincter. Finally pudental nerve contributes to the innervation of

the skin on the posterior thigh.

Clinical importance: irritation of the pudental nerve is a direct cause of sexual

dysfunction in men and women (e.g., erectile dysfunction, dryness of vagina, pain

during intercourse, etc.) and sensory abnormalities (e.g. tingling, numbness) on

the posterior thigh. (Novakovic et al)

22

FOOTDROP

Footdrop is a relatively common deficit among the neurological disorders, which has different causes with various levels of involvement in neuromuscular system, including central nervous system (brain cortex, spinal cord), fifth lumbar root, peripheral nerves and muscles. Peroneal nerve injury at the fibular head has been reported to be the most common cause of footdrop, which can be due to infarct, tumor or leprosy but the vast majority of lesions are traumatic . Footdrop has many causes. Various pathologic lesions at different anatomic levels in nervous system can lead to it, but for this present discussion we confine ourselves to the peripheral nerve ethiologies. The deep peroneal nerve innervates the muscles that allow dorsiflexion of the foot. Foot dorsiflexion is mainly due to tibialis anterior weakness which can lead to footdrop. This muscle is also a foot invertor. Roots of L4,5-S1, but predominantly L5 innervates it. Peripheral nerve lesions that lead to footdrop consist of L5 radiculopathy (the inversion of the foot is also impaired because of the tibialis posterior involvement), sciatic and deep peroneal nerves lesions. In the sciatic nerve lesions, there are evidence of damages to the tibial innervated muscles, both clinically (such as weak plantar flexion of the foot) and electrophysiologically. Denervation in the short head of biceps can also be detected by electromyography. Causes include trauma such as hip, pelvic and femoral shaft fractures, injections in the gluteal region and other uncommon ethiologies such as vaginal operations, difficult delivery, traumatic hematoma in the posterior thigh, tumors, use of bicycle and compression from an arterial aneurysm. Sitting for a long period with legs flexed and abducted (lotus position) under the influence of narcotics or barbiturates or lying flat on a hard surface, ischemic necrosis of the sciatic nerve in diabetes melitus or polyarteritis nodosa and Idiopathic forms were also described (Victor M, Ropper AH. Adams et al). Peroneal nerve may be involved by pressure during an operation, sleep or from tight plaster casts, obstetric stirrups, habitual and prolonged crossing of the legs while seated (especially in patients who lost a great deal of weight), tight knee boots,diabetic neuropathy, fractures of the upper end of the fibula or tibia, Baker’s cyst, muscle swelling or small hematomas behind the knee in the asthenic athletes (Victor M, Ropper AH. Adams et al), repeated squatting, minor athletic injury, dislocation of the knee, thrombosis or embolism of the femoral or popliteal arteries, pressure from the ganglion cysts or hematoma in hemophiliac and lipomatosis in the popliteal fossa, leprosy and fabella (sesamoid bones in the

23

gastrocnemius) (Liveson JA et al). Patients described in this article are examples of peroneal nerve injury at the fibular head. As the site of injury correlates with the dominant hand, it can be deduced that the particular action of the patient (harvesting and weeding) was responsible for injury and not the sitting or squatting. This may be due to a repeated trauma by the hand of the patient to the peroneal nerve at the fibular head or it may be due to particular sitting position that the patient assumes. As a matter of fact, during harvesting or weeding a farmer squates, bends the dominant knee completely, but the other knee partially, and then doing repeated to and for movements of the dominant hand to cut the plants or weeds. Whether the complete flexion of the knee or the repeated trauma to the head of fibula by the forearm, injures the peroneal nerve is not fully understood. The relative young age of the patients is noteworthy. Young workers may not be as experienced as the older farmers in their tasks or perhaps they work more vigorously. Also the relatively good prognosis of footdrop in these patients is important. However as one can not do a second electrophysiologic study the possibility of residual subclinical sequels remains open. (M. Ghaffarpour, A. Dolatabadi and M.H. Harirchian et al)

24

References

Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), pps 470-471, 476, 478, 482.

Beaton L.E., Anson B.J. The Sciatic Nerve and the Piriformis Muscle: Their

Relationship a Possible Cause of Coccygodynia. J. Bone Joint Surg, (Br) 20:686-688,

1938.

Lee C.S., Tsai T.L. The Relation of the Sciatic nerve to the Piriformis Muscle. J.

Formosan Med Assoc., 73:75:75-80, 1974.

Lymansky Y.P., Macheret E.L., Vaschenko E.A. The Neurological Symptoms of the

Spodylosis. 'Zdorovie', Kiev, 1988.

Retzlaff E.W., Berry A.H., Haight A.S., Parente P.A. The Piriformis Muscle

Syndrome. JAOA, 73:799-807, 1974.

Ripani M., Continenza M.A., Cacchio A., Barile A., Parisi A., De Paulis F. The

Ischiatic Region: Normal and MRI Anatomy. J. Sports Med Phys Fitness, Sep,

46(3):468-475, 2006.

Russell J.M., Kransdorf M.J., Bancroft L.W., Peterson J.J., Berquist T.H., Bridges

M.D. Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Sacral Plexus and Piriformis Muscles.

Skeletal Radiology, Aug, 37(8):709-713, 2008.

Berzon JL, Dueland R: Cauda equina syndrome: Pathophysiology and report of

seven cases. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 15:635, 1979.

P.Novakovic, MDPART I: ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF PIRIFORMIS MUSCLE

(PM).

Gertzbein SD, Tile M, Gross A et al: Autoimmunity in degenerative disk disease of

the lumbar spine. Orthop Clin North Am 6:67, 1975.

Jaeckle KA. Neurological manifestations of neoplastic and radiation-induced

plexopathies. Semin Neurol. Dec 2004;24(4):385-93. [Medline].

Keith L. Moore, Ph.D, Arthur F. Dalley, Ph.D. Clinically Oriented Anatomy, fifth

edition, 2006.

M. Ghaffarpour, A. Dolatabadi and M.H. Harirchian. FOOTDROP IN THE FARMERS:

CLINICAL AND ELECTROMYOGRAPHICAL STUDY, 2002.

Jones HR, Felice KJ, Gross PT. Pediatric peroneal mononeuropathy: A clinical and

electro-myographic study. Muscle Nerve 1993; 16: 1167.

![1. brachial plexus & its applied anatomy[1]](https://static.fdocuments.net/doc/165x107/554b284fb4c905da088b492a/1-brachial-plexus-its-applied-anatomy1.jpg)