“TWENTY-TWO PROJECTS COMPLETE. THIRTY-SEVEN...

Transcript of “TWENTY-TWO PROJECTS COMPLETE. THIRTY-SEVEN...

THE ART ECONOMIST 3938 THE ART ECONOMIST

Rather unexpectedly for a movie about the art world, Islands, the documentary that Al and David Maysles made about Christo and Jeanne-Claude in the early ’80s, comes off as tense, dramatic, and almost thriller-esque. The artists are

trying to make three separate, hugely ambitious projects happen, and bumping their heads against stone walls on each. Jacques Chirac, the Mayor of Paris, refuses to allow the artist to wrap the oldest bridge in Paris, the Pont Neuf. The viewer may think, well, of course he would refuse. But Christo, politely intense, black hair cascading to his shoulders, dismantles the logic of the mayor’s posi-tion. Chirac, now all creamy smiles, promises his approval but says

that this must be kept secret until after a forthcoming election. You may be startled to see this svelte maneuver on camera, but that was a generation before YouTube.

The film flashes forward to the mid-’90s and we see Willy Brandt, the German chancellor, advising the Christo team on how they can get permission to wrap the German parliament, the history-drenched Reichstag. We also hear Dade County commissioners in July 1982 voting yay or nay—several apparently obdurate nays—on whether Christo should be allowed to surround eleven islets in Bis-cayne Bay with floating, woven pink polypropylene.

All three projects happen. It has not always been so.

“ T WE N T Y-T WO PROJ EC T S COM P L E T E.T H I RT Y- S EV E N FA I L U R E S ! ”

How Christo and Jeanne-Claude have wrapped up the art world.BY A N T H O N Y H A D EN - GU ES T

Opposite page:

Christo and Jeanne-

Claude, Wrapped

Coast, Little Bay,

Sydney, Australia,

One Million Square Feet,

1968-69, Photo by Harry

Shunk, © 1969 Christo,

Courtesy of the artist.

This page top:

Christo and Jeanne-

Claude, The Pont Neuf

Wrapped, Paris, 1975-85,

Photo by Wolfgang Volz,

© 1985 Christo,

Courtesy of the artist.

This page bottom:

Christo and Jeanne-

Claude, Wrapped

Reichstag, Berlin,

1971-95, Photo by

Wolfgang Volz, © 1995

Christo, Courtesy

of the artist.

“Twenty-two projects complete. Thirty-seven failures!” Christo told me, recently. He remains politely intense, but the cascade of hair is white. And the failures never final.

Over The River, the project upon which he is currently working, will involve the suspen-sion of white woven fabric above sixty kilome-ters of the Arkansas River as it winds through Colorado. The history of the project has been characteristically zigzag.

In late 1991, Christo and Jeanne-Claude had finished The Umbrellas, a project in which blue and yellow umbrellas were installed in a rice field in Japan and meadowland in Califor-nia, and had already settled on Over The River as their next undertaking, when an old project came back to life.

“We started to work on the Berlin Project, the Wrapped Reichstag in 1971,” Christo says. “That project was refused in 1977. The second refusal was in 1981. The third refusal was in 1987. When we had just finished The Umbrellas, we received a letter of congratulations from the Bundestag president, the Speaker of the House, who said there is now a great chance that we can get permission for the Reichstag.”

They flew out to Bonn and began lobbying the 660 deputies of the German parliament. This is the process the Maysles movie records. It looked hopeful, but there had been many last minute turn-downs so, in advance of the vote in the Bundestag, Christo and Jeanne-Claude returned to work on Over The River. But, the Reichstag project was approved; Christo and Jeanne-Claude returned to Germany.

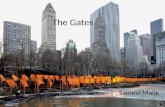

Certain Contemporary artists, such as Hirst, Murakami and Banksy, are managing their careers to one degree or another. Christo and Jeanne-Claude, who died of an aneurysm in November 2009, have wholly managed their career almost from the beginning. After the termination of The Gates project in Central Park, the Harvard

Business School published Christo and Jeanne-Claude: The Art of the Entrepreneur, a 22-page study that incorporated a break-down of costs on The Gates, including from 2003 such items as $5,501,025 for Project Supplies and Expenses and $202,597 for Consulting Fees. Total expenditures for 2003 and 2004 were a tad under $15 million.

The Gates had been a shimmering revelation. And a money spinner, so it generated offers. “After The Gates was finished we had a hundred mayors from around the world asking us to come and install The Gates in their park,” Christo says. “Or wrap my parlia-ment. Or wrap my city hall.”

No such proposals were accepted, nor commissions, grants or sponsorships. Each project is sui generis. “All our projects, they are season projects,” Christo says. “The Surrounded Islands was a spring project. Because in summer come the hurricanes. The Gates project was a winter project, because the trees are leafless. In the summertime, Central Park is like a forest. And the Over The River project is a summer project, because we like to have the rafters. It is a beautiful rafting river.”

THE ART ECONOMIST 4140 THE ART ECONOMIST

It was 1962 when a Düsseldorf arts entrepreneur, Charles Wilp, brought Christo and Jeanne-Claude to my place in the Pheasantry Studios on London’s Kings Road. Christo had a project in mind, the wrapping of a naked woman, and Wilp, who knew my neighbor was the fashion photographer, Claude Virgin, had asked if I could provide a willing party, which I did. Her name was Ruth Ebling and she sweated buckets, losing her Vidal Sassoon. But Wrapped Woman was, okay, a wrap. I was a working photographer back then and took the picture.

Not long after, I went to see Christo and Jeanne-Claude in their Paris studio/apartment on the Ile Saint-Louis. Christo is Bulgarian. He studied art in Prague, acquiring classic Beaux Arts skills, and made his getaway to the West by stowing away on a train in 1957. He studied art in Vienna for a semester and went to Paris the following year, where he began to make a living by executing portraits for a clientele that included the Gallimards and Helene de la Rochefoucauld. The portraits were deftly done, but Christo distanced himself from them by signing them with his surname, ‘Javacheff.’

Jeanne-Claude, whose mother, Precilda, had fought in the French Resistance and whose stepfather was General Jacques de Guillebon, was such a portrait commission. Painter and subject found that they shared a birthday, June 13, 1935. They soon found they shared much more: Jeanne-Claude was engaged, but she was pregnant by Christo when she was married, and returned to him immediately after the honeymoon.

Their place on the Ile Saint-Louis was poky, engaging, and in some ways, a relic of a Paris long gone. “People still made pee-pee and caca in back yards,” Christo says. “And most important, it had a telephone! To have a telephone in Paris in 1958, you needed to know somebody important. The waiting list was two, three years.”

There was work of Christo’s there, paint cans and bottles that Christo had wrapped in canvas, but I don’t think it was until later that I saw the translucent plastic package within which you can see a portrait of Jeanne-Claude. The package is signed CHRISTO.

The Nouveau Realists, a group that included Yves Klein, Daniel Spoerri and Niki de Saint Phalle, were the most active group in the Paris art world at the time. They had been named by the critic, Pierre Restany, who wrote a 1960 manifesto, Nouveau Realisme—

new ways of perceiving the real. Christo was soon associated with them. “In August of ‘61 the Berlin Wall was built,” Christo says. “In September of ’61, I made a study for a wrapped public building, and also the study for The Iron Curtain, the wall of oil barrels.”

Both were included in his first exhibi-tion, which was in Cologne, where also he made his first public work, Dockside Pack-ages, on a harbor quay. They remained in situ for two weeks. For almost a year he worked with the City of Paris, trying to obtain permission to erect The Iron Curtain. Frustrated in June 1962, he did it as a guerrilla action in the conveniently

narrow Rue Visconti. Christo had come to attention and not just with the Paris art world. Amongst those who visited the Rue Visconti was a New York dealer he had met the year before: Leo Castelli.

Castelli already had seen such new work of Christo’s—his pack-ages and his replicas of shrouded, empty storefronts. The Rue Vis-conti piece convinced him.

“He told me that if I came to New York, he would show my work in his gallery on East 77th,” Christo says. “You come to New York. You will have a visa! It was to have a piece in a group show. But with Leo Castelli!”

Christo and Jeanne-Claude stayed in the Chelsea Hotel from Feb-ruary to May while Christo made a life-size storefront. The show,

Left:

Christo and Jeanne-Claude,

Wrapped Trees, Fondation

Beyeler and Berower Park,

Riehen, Switzerland, 1997-98,

Photo by Wolfgang Volz,

© 1998 Christo, Courtesy of

the artist.

Center:

Christo and Jeanne-Claude,

Dockside Packages, Cologne

Harbor, 1961, Photo by Stefan

Wewerka, © 1961 Christo,

Courtesy of the artist.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Wall of Oil Barrels - The Iron Curtain, Rue Visconti, Paris, 1961-62,

Photo by Jean-Dominique Lajoux, © 1962 Christo, Courtesy of the artist.

THE ART ECONOMIST 4342 THE ART ECONOMIST

which opened on May 1,1964, was called Four Artists on Four East 77th, and it is yet another indication of the ups and downs of an art career that the other three were Richard Artschwager, who has a hefty reputation, Robert Watts, who is a fascinating footnote, and Alex Hay, who is unknown to me. Christo’s Store Front did not then sell, but is now in the collection of the Smithsonian in Washington DC.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude now were living in Howard Street, off Broadway, a couple of blocks above Canal. “We were illegal aliens for three years. Leo was our principal sponsor,” Christo says. But global-ism lay way in the future and their welcome from the gallery artists was not enthusiastic. “They were furious that Leo was showing me. That is no secret,” Christo says. He adds that they were particularly enraged when Horace and Holly Solomon, who were then influen-tial collectors, bought a Store Front. “Will they still have room on

their walls? They thought the Store Front was too big. I was speaking very poorly English then. There was always this resistance.”

Christo showed another piece at Castelli in 1966, but never joined the gallery roster. Nor has he ever had a primary dealer. “Nobody was interested,” he says. “Later, of course. But in the beginning, nobody. This is why we are the biggest collectors of our work. You know, we have incredible early pieces, valuable pieces that are much more expensive than the drawings. We are the biggest collectors of our work. We are our own curators. We have our principal storage in Basel.”

Christo had dreamed of wrapping a public building since 1961. “A museum or a kunst-halle,” he says. He and Jeanne-Claude would find an enthusiastic supporter, but one who failed to greenlight the project again and again. In 1964, his efforts to wrap 2 Broad-way were slapped down. In 1966, ‘67, they

were pursuing an opportunity in Italy. “We never got it,” Christo says. “In 1968, we tried to wrap Number 1 Times Square. The former New York Times building. At that time, it was the headquarters of the Allied Chemical Corporation. We never succeeded.”

Meanwhile, Bill Rubin, the director of MoMA, had been organizing an exhibition, Dada, Surrealism And Their Heritage. “And he was bor-rowing several pieces,” Christo says. They were friendly with Rubin, who spoke French, so language was not a problem. “Bill Rubin was very keen that for the opening we wrap MoMA,” Christo says. “It would happen in the spring of 1968. We made scale models, draw-ings, everything. But we were never able to secure the insurance, because there was a famous fire in MoMA in the late ’60s. The insur-ance company was saying it’s impossible. This collection is priceless!”

Undeterred, they switched their attention to a smaller museum, the Kunsthalle in Bern, Switzerland. The director was excited by the project, and two of their collectors, one of whom was the chairman of Nestle, were on the board. In the summer of 1968 that became their first successfully wrapped public building.

Their projects can be turned down at so many stages that Christo and Jeanne-Claude always would have several on the go. Another unrealized project is The Mastaba, a huge oil drum structure, which grew from the oil drum sculptures that he made in Cologne Harbor and the Rue Visconti.

“John de Menil saw sketches for it and said, look, let’s do a Mastaba in Texas,” Christo explains. “It’s natural! Texas has oil. I go to Houston. There was a proposal to do a Mastaba between Houston and Galveston. Near the highway. Nothing happened. It didn’t gen-erate any enthusiasm.” The Deer Park in Otterlo, Holland, seemed a promising venue, but there was a last moment turn-down.

The notion of wrapping the California coastline germinated when Christo and Jeanne-Claude were visiting Peter Selz, who had moved from New York to California to become the founding director of the Berkeley museum. That project was slapped down, too.

Then a conversation with a young Australian collector led to a suggestion that Christo do something on that continent. “Jeanne-Claude tells me they have a huge coastline! The biggest in the world!” says Christo. The collector was asked to scout out a spot. Christo and Jeanne-Claude were precise.

“It should not be very big. A mile, a mile and a half. And it should not be far away. Because of the workers. It needs to be close to Mel-bourne or Sydney.

“He found it. It was five miles from the center of Sydney. It was a beautiful area. A little bay. So we did the Wrapped Coast in ‘69. The wind! The Pacific Ocean! The beach! One and a half miles! And I dislocated my shoulder on the rocks. Now we are older. But in 1969!”

Christo and Jeanne-Claude beefed up their business model in 1970, at the suggestion of their lawyer, Scott Hodes, before they un-dertook the Running Fence project. “Scott said we should create a corporation, not a non-profit, to build our project, to sell our original works of art and to buy back our original works of art,” Christo says. “That corporation is CVJ Corporation. Those are my initials. Christo Vladimir Javacheff. And when we are building projects, that corpora-tion will create subsidiaries. For example, during Running Fence there was the Running Fence Corporation. The CVJ Corporation was sup-plying the money. And when the Running Fence was finished, then the corporation was dissolved.” Subsequently, a corporation has been created for each project as soon as the permitting comes through.

“We do that because we are working with engineers, building con-tractors, construction companies. They say ‘who are you?’ Normal! I work with that bank. So you are a reliable person. We live in a capital-ist society. This project is building things. Like building a bridge or a highway. And each corporation that builds a project, they have a project director, they have a coordinator, they have a whole staff.

“Like all corporations, it needs to have good relations with banks. We cannot say to our workers on Friday that we cannot pay you because some collectors do not pay, or some museums don’t pay, or

some dealer promises, but he does not send the money. This is very common in the art world.

“That is why we work with many banks all around the world, so that we have a standby line of credit. The Reichstag project cost us a huge amount of money. Because we hadn’t finishing paying for the Umbrellas project, which was just three years before, we were obliged to take a big line of credit from Deutsche Bank. We paid back the line of credit, but the interest was over two million dollars above the principal.”

It’s the art in the Basel vault that guarantees the loans.“The bank evaluates everything. Basically it is one to four. For

one dollar we need four dollars guarantee. And it is our prices! Not Christie’s, Sotheby’s prices! Our prices. And this is how it was done since the Running Fence.”

If it is Christo’s early art that guarantees the loans, it is the art that each project generates—the drawings, the collages, the models—that repays them. “I even frame my drawings myself,” Christo says. “They are all original, unique pieces. Not done by assistants.” He already had made most of the Running Fence art when he, Jeanne-Claude and their team arrived in Petaluma, California, to battle for local approvals. This was the first and only major project that I fol-lowed more or less from start to finish.

It was proposed that this eighteen-foot high fence of woven nylon fabric—Christo compares the fabrics he loves to use to leaves and human skin—runs for twenty-four and a half miles through un-dulant land in Sonoma and Marin counties, and remain in situ for fourteen days. Most of the land was held privately by ranchers, and permissions would be required from each and every one, as would

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, Wrapped, 1969, Photo by Harry Shunk,

© 1969 Christo, Courtesy of the artist.

Christo, The Mastaba, Project for United Arab Emirates, 2009, collage in two

parts, pencil, charcoal, wax crayon, pastel, technical data and map, 15 x 65 in.

and 42 x 65 in. (38 x 165 cm and 106.6 x 165 cm), Photo by Wolfgang Volz, © 2009

Christo, Courtesy of the artist.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Running Fence, Sonoma and Marin Counties, California, 1972-76, Photo by Wolfgang Volz, © 1976 Christo, Courtesy of the artist.

THE ART ECONOMIST 4544 THE ART ECONOMIST

the approval of a number of local bodies. The hearings, the meet-ings, were as illuminating as they were exhausting.

“We are the only artists in the world whose work is discussed before physically it exists,” Christo told me recently. “Our work is discussed by thousands, sometimes by hundreds of thousands of people, before physically it exists. How beautiful it will be! How awful it will be! Ugly! In the minds of people who try to stop us and the minds of people who want to help us.”

The ranchers of Sonoma and Marin were mostly conservative, and by no means a target audience for a Contemporary artwork, but clearly they were impressed by the nuts-and-bolts-y thorough-ness of the engineering involved, and you could sometimes sense that—zap! An individual rancher had fallen for the concept, too, taken a leap of faith.

But there was vocal opposition. There always is. Is this intermi-nable process part of the art?

“Of course it’s part of the art!” Christo says.At one stage of the Running Fence hearings, he told the opposition

that they were part of his art, like it or not.Local artists, incidentally, could be snippy—one referred to

Christo as “a New York superstar” —but Charles Schulz, whose Peanuts ranch was nearby, spoke out strongly in support of the project. He would later incorporate Christo into several strips. In one, Snoopy gets his doghouse wrapped.

The project was approved. Running Fence was a thing of beauty. For fourteen days.

In 2003, after the great cartoonist’s death, Christo wrapped a doghouse and presented it to the Charles M. Schulz Museum.

Not wishing to confuse the market, Jeanne-Claude and Christo only let it be known they have been co-creators of their major projects in 1994. “We always work together on the big projects. Always!” Christo told me. So what effect will her death whave on Works in Progress? Not a great deal. Death was always a consider-ation. Christo and Jeanne-Claude always flew on separate planes, for instance. And in January 2003, when finally they received permis-sion to do The Gates and costed it, they insured Christo’s life for $20 million dollars. “Jeanne-Claude said we have worked on that project for over twenty years. We need to finish it,” Christo says. “I was insured, so that if something happens to me, Jeanne-Claude con-tinues the project.” Work on Over The River, a project on a stretch of river chosen after Christo and Jeanne-Claude had investigated 89 rivers in seven mountain states, continues, as well.

Christo still lives on Howard Street, a building he now owns, and his drawing room is spare, filled with oatmeal light. There are Over The River collages on the wall, some early brown-paper pack-ages and some wrapped paint-cans, just like the ones I saw on the Ile Saint-Louis. Beside him was an oblong mountain of thick files.

“This study will be released at the end of May,” he said. “One thou-sand, five hundred and sixty pages. Two and a half million dollars! Now that will be released. It will be on the website. It will be available to everybody. That study will respond to forty thousand letters. They are not hired by us. They are hired by the federal government. And we cannot talk to them. Because they are totally independent.

“Then the federal government will have sixty days. To do, or not to do.”

We looked at the Over The River collages.

“Our projects are the real thing. That is the difference. Most art is illustration. All our projects are the real thing. It is not theatrical. It is not improvisation. It is not spectacle. It is the real thing. The pho-tograph of the Wrapped Reichstag is an illustration of the Wrapped Reichstag. The film is an illustration. But for fourteen days in 1995, it was the Reichstag Wrap—the real thing!

“We got letters saying we would be killed. We had seventeen bodyguards for one year. The German government was scared to death that we would be targeted by Neo-Nazis. When we arrived for the building, we went to the hospital to give our blood. So that if we were wounded, they had our blood.”

He laughed.“They rented an entire hotel floor for us. Nobody else could

go there. This was not invented. It is not theatre. This is not little things. It is the real thing. Jeanne-Claude was always saying, all our projects, they are like slices of our life.”

The Over The River process has been different from that of the Reichstag, but hardly less demanding. “The state of Colorado is rep-resented by two senators and five congressmen,” Christo says. “It was very important that they write letters to the Secretary of the Interior to President Obama, supporting the project. And we spent an enormous amount of time going from office to office, explaining the project. And they wrote the letters, supporting the project. Re-publicans and Democrats.

“Normal artists would think that’s terrible. But we enjoy this enormously.”

That “we.” Christo and Jeanne-Claude are a team still. It was at her insistence that Christo and his team meet with the Secretary of

the Interior, Ken Salazar, in Washington, to discuss Over The River last November while she was in the hospital. It was the day before she died. The work goes on.

“We live to talk to people. Normally, artists have horror stories about bureaucracy, but for us it was very exciting.”

It takes two years after a project has been approved for it to be accomplished, so if Over The River is indeed approved, 2014 looks like the earliest start date.

“Then it will be the real Arkansas River. Sixty kilometers! Of course, there will be film and photographs. But it will be the real thing for fourteen days. It is not my invention. It is the truth. The wind, the sun. They are not spectacles, they are not theatre. This is why we never do the same thing, ever! We will never build another Gates. We will never surround another island. We will never wrap another parliament. We will never make another Running Fence. Because each project is a completely new image.” �

ANTHONY HADEN-GUEST IS A BRITISH-AMERICAN WRITER, REPORTER, CARTOONIST AND ART

CRITIC BASED IN NEW YORK AND LONDON. THE ART NEWSPAPER, NEW YORK OBSERVER, VANITY

FAIR, THE DAILY BEAST AND THE NEW YORKER ARE BUT A FEW OF THE NOTABLE PUBLICATIONS

THAT HAVE CARRIED HIS BYLINE.

Opposite page left:

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, The

Wall - 13,000 Oil Barrels, Indoor

Installation and Exhibition,

Gasometer, Oberhausen,

Germany, 1999, Photo by

Wolfgang Volz, © 1999 Christo,

Courtesy of the artist.

Opposite page right top to bottom:

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, The

Umbrellas, Japan-USA, 1984-91,

(California, USA site), Photo by

Wolfgang Volz, © 1991 Christo,

Courtesy of the artist. Christo and

Jeanne-Claude, The Umbrellas,

Japan-USA, 1984-91, (Japan site),

Photo by Wolfgang Volz, © 1991

Christo, Courtesy of the artist.

This page:

Christo, Over the River, Project

for Arkansas River, State of

Colorado, 2009, Collage, Pencil,

enamel paint, wax crayon, fabric

sample, aerial photograph with

topographic elevations and tape

on tan board, 11 x 14 in. (28 x 35.5

cm), Photo by André Grossmann,

© 2009 Christo, Courtesy

of the artist.