“The earth is but one country, and mankind its citizens ... · characterization of terrorism as...

Transcript of “The earth is but one country, and mankind its citizens ... · characterization of terrorism as...

I N S I D E

“The earth is but one country, and mankind its citizens” – Bahá’u’lláh

Newsletter of the Bahá’íInternational Community

July-September 2005Volume 17, Issue 2 Innovative and popular, Youth Can Move the World offers

leadership training for young people to help them avoid alcoholand drug abuse, HIV/AIDS, and other social problems.

In Guyana, young people take the leadin an effort to avoid risky behaviors

Guyana, continued on page 9

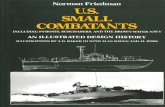

Review: Restless Souls— Leigh Eric Schmidtexplores the quest forenlightenment in theUnited States at the endof the 19th century.

In Germany, Bahá’íscelebrate 100 years ofcrisis and achievement.

At Green Acre, the first“modern” peace treatyand a woman’s contri-bution to it is com-memorated.

Perspective: The UNat 60: The Search forValues in an Age ofTransition.

13

2

16

4

GEORGETOWN, Guyana — With an empty Coke bottle for a pint of rum and a whiteplastic chair the only other prop, the skit performed by five young men and women

during a recent meeting of the Future Club here told a story that is unfortunately all toofamiliar in this vibrant South American country.

A husband drinks too much and beats his wife, shouting and swearing at her for failingto have dinner ready on time. Crying and inconsolably depressed after many such epi-sodes, she decides to take her own life. Her planned method is to drink “Gramazone,” thelocal name for the widely available herbicide Paraquat, which offers a certain if painfullyslow death.

However, as performed before an audience of several dozen other young people fromevery section of this gritty coastal capital one recent day, the young woman’s friends inter-vene, pleading with her not to take her life.

And so the heroine, played by 16-year-old Rayana Jaundoo, triumphantly throws the poi-son aside. “I have learned I don’t care what other people do and what other people say,” she says,breaking character and addressing the audience directly. “I can live a positive life.”

Although a little overplayed, it is a happy ending, just the sort encouraged by the youngfacilitators of an innovative and highly successful youth leadership training program here,known as Youth Can Move the World (YCMTW).

Youth Can Move the World program coordinator Farah Beepat, center, discusses ways to avoid domesticviolence with 11- to 15-year-olds at the Uitvlugt Secondary School in Uitvlugt, Guyana.

ONE COUNTRY / July-September 20052

P E R S P E C T I V E

is published quarterly by theOffice of Public Information ofthe Bahá’í InternationalCommunity, an internationalnon-governmental organiza-tion which encompasses andrepresents the worldwidemembership of the Bahá’íFaith.

For more information on thestories in this newsletter, orany aspect of the Bahá’íInternational Community andits work, please contact:

ONE COUNTRYBahá’í InternationalCommunity - Suite 120866 United Nations PlazaNew York, New York 10017U.S.A.

E-mail: [email protected]://www.onecountry.org

Executive Editor:Ann Boyles

Editor:Brad Pokorny

Associate Editors:Vladimir Chupin (Moscow)Christine Samandari-Hakim(Paris)Kong Siew Huat (Macau)Guilda Walker (London)

Editorial Assistant:Veronica Shoffstall

Design:Mann & Mann

Subscription inquiriesshould be directed to theabove address. All materialis copyrighted by the Bahá’íInternational Communityand subject to all applicableinternational copyright laws.Stories from this newslettermay be republished by anyorganization provided thatthey are attributed asfollows: “Reprinted fromONE COUNTRY, thenewsletter of the Bahá’íInternational Community.”

© 2005 by The Bahá’íInternational Community

ISSN 1018-9300

Printed on recycled paper

The Search for Values in an Age of Transition

[Editor’s note: The following Perspective edi-torial is adapted from “The Search for Valuesin an Age of Transition,” issued recently bythe Bahá’í International Community for the60th anniversary of the United Nations. Thefull statement is at: http://www.onecountry.org/e172/BIC_UN_60th.htm]

In 1945, the founding of the United Nationsgave a war-weary world a vision of what

was possible in the arena of internationalcooperation and set a new standard by whichto guide diverse peoples and nations towardsa peaceful coexistence. Sixty years later, thequestions that fuelled the San FranciscoConference assert themselves anew: Whyhave the current systems of governance failedto provide for the security, prosperity, andwell-being of the world’s people?

The challenges facing the internationalcommunity are numerous: Weak states haveerupted in conflict, lawlessness, and massiverefugee flows; the advancement of men andboys at the expense of women and girls hassorely limited the creative and material capaci-ties of communities to develop; the neglect ofcultural and religious minorities has intensi-fied ancient prejudices setting peoples andnations against one another; an unbridled na-tionalism has trampled the rights and oppor-tunities of citizens in other nations; and nar-row economic agendas exalting material pros-perity have often suffocated the social andmoral development required for the equitableand beneficent use of wealth.

Such crises have laid bare the limits oftraditional approaches to governance andput before the UN the inescapable questionof values: which values are capable of guid-ing the nations and peoples of the world outof the chaos of competing interests and ide-ologies towards a world community capableof inculcating the principles of justice andequity at all levels of human society?

Significantly, the question of values andtheir inextricable link to systems of religionand belief has emerged on the world stageas a subject of consuming global importance.A growing number of leaders and delibera-tive bodies acknowledge that the full impactof religion-related variables on governance,

diplomacy, human rights, development,notions of justice, and collective securitymust be better understood.

Among humanity’s diverse civilizations,religion has provided the framework for newmoral codes and legal standards, which havetransformed vast regions of the globe from brut-ish and often anarchical systems to more so-phisticated forms of governance. The existingpublic debate about religion, however, has beendriven by extremists on both sides — thosewho impose their religious ideology by force,whose most visible expression is terrorism —and those who deny any place for expressionsof faith or belief in the public sphere. Neitheris representative of the majority view, and nei-ther promotes a sustainable peace.

At this juncture of our evolution as a glo-bal community, the search for shared values— beyond the clash of extremes — is para-mount for effective action. A concern with ex-clusively material considerations will fail toappreciate the degree to which religious, ideo-logical, and cultural variables shape diplomacyand decision-making. In an effort to movebeyond a community of nations bound by pri-marily economic relationships to one withshared responsibilities for one another’s well-being and security, the question of values musttake a central place in deliberations, be articu-lated and made explicit.

We can no longer be content with a pas-sive tolerance of each other’s worldviews;what is required is an active search for thosecommon values and moral principles whichwill lift up the condition of every woman,man, and child, regardless of race, class, re-ligion, or political opinion.

The emerging global order, and the pro-cesses of globalization that define it, must befounded on the principle of the oneness ofhumankind. This principle, accepted and af-firmed as a common understanding, providesthe practical basis for the organization of rela-tionships between all states and nations. Theincreasingly apparent interconnectedness ofdevelopment, security, and human rights on aglobal scale confirms that peace and prosper-ity are indivisible — that no sustainable ben-efit can be conferred on a nation or commu-nity if the welfare of the nations as a whole is

ONE COUNTRY / July-September 2005 3

ignored or neglected.The principle of the oneness of human-

kind does not seek to undermine nationalautonomy or suppress the cultural and in-tellectual diversity of the peoples and na-tions of the world. Rather, it seeks to broadenthe basis of the existing foundations of soci-ety by calling for a wider loyalty, a greateraspiration than any that has animated thehuman race. Indeed, it provides the moralimpetus needed to remold the institutionsof governance in a manner consistent withthe needs of an ever-changing world.

We recommend the following towards amore just and effective United Nations:

Human Rights and the Rule of Law —The grave threats posed by religious extrem-ism, intolerance, and discrimination requirethe United Nations to address this issueopenly and earnestly. We call on the UN toaffirm unequivocally an individual’s right tochange his or her religion.

The Office of the High Commissioner ofHuman Rights, bolstered by the requisitemoral, intellectual, and material resources,must now become the standard-bearer in thefield of human rights. Further, as one of themost effective instruments for the protectionof human rights, Special Procedures shouldreceive adequate budgetary and administra-tive support.

Development — While the search for a sci-entific and technologically modern society is acentral goal of human development, it mustbase its educational, economic, political, andcultural structures on the concept of the spiri-tual nature of the human being and not onlyon his or her material needs.

The capacity of people to participate inthe generation and application of knowledgeis an essential component of human devel-opment. Priority must be given to education,and the UN should consider that in terms ofeconomic investment, the education of girlsmay well yield the highest return of all in-vestments available in developing countries.

The rich countries of the world have a moralobligation to remove export and trade distort-ing measures that bar the entry of countriesstruggling to participate in the global market.The Monterrey Consensus, which recognizesthe importance of a ‘more open, rule-based,non-discriminatory and equitable’ system oftrade, is a step in the right direction.

Democracy — The exercise of democ-racy will succeed to the extent that it is gov-erned by the moral principles that are inharmony with the evolving interests of a rap-

idly maturing human race. These include:trustworthiness and integrity needed to winthe respect and support of the governed;transparency; consultation with those af-fected by decisions being arrived at; objec-tive assessment of needs and aspirations ofcommunities being served; and the appro-priate use of scientific and moral resources.

Collective Security — Based on the un-derstanding that in our interconnected world,a threat to one is a threat to all, the Bahá’í Faithenvisions a system of collective security withina framework of a global federation, in whichnational borders have been conclusively de-fined and in whose favor all the nations of theworld will have willingly ceded all rights tomaintain armaments except for purposes ofmaintaining internal order.

To address the democracy deficit and re-lentless politicization of the Security Coun-cil, the United Nations must move towardsadopting a procedure for eventually elimi-nating permanent membership and vetopower. Alongside procedural reforms, a criti-cal change in attitude and conduct is needed.Member States must recognize that in hold-ing seats on the Security Council, they havea solemn moral and legal obligation to act astrustees for the entire community of nations,not as advocates of their national interests.

We agree with the Secretary-General’scharacterization of terrorism as any action“intended to cause death or serious bodilyharm to civilians or non-combatants with thepurpose of intimidating a population or com-pelling a Government or an international or-ganization to do or abstain from doing anyact.” Moreover, it is imperative that prob-lems such as terrorism be consistently ad-dressed within the context of other issuesthat disrupt and destabilize society.

Steps should be taken to increase the par-ticipation of women at all levels of decision-making in conflict resolution and peace pro-cesses, locally, nationally, and internationally.

The task of establishing a peaceful worldis now in the hands of the leaders of thenations of the world. Their challenge is torestore the trust and confidence of their citi-zens in themselves, their government, andthe institutions of the international orderthrough a record of personal integrity, sin-cerity of purpose, and unwavering commit-ment to the highest principles of justice andthe imperatives of a world hungering forunity. The great peace long envisioned bythe peoples and nations of the world is wellwithin our grasp.

In an effort to

move beyond a

community of

nations bound by

primarily

economic

relationships to

one with shared

responsibilities

for one another’s

well-being and

security, the

question of values

must take a

central place in

deliberations, be

articulated and

made explicit.

ONE COUNTRY / July-September 20054

C O M M E M O R A T I O N

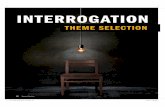

STUTTGART, Germany — Capping amultifaceted observance of the 100th an-

niversary of the Bahá’í Faith in Germany,some 1,800 participants gathered in thissouthwestern German city to commemoratea history both “darkened” by crisis and“highlighted” by achievement.

People came from every region of Ger-many and at least 25 other nations for theday-long jubilee, held 10 September 2005at the Stuttgart Congress Center.

Featuring prayers, speeches, music, andtheatrical performances, the program tooknote of the “dark” times when the Bahá’íFaith was banned under Nazism — and ofthe joyous highlights that have followedduring modern Germany’s reconstructionand prosperity.

Performances, including old film clipsand photographs, depicted events such asarrival of the first Bahá’í in Germany in 1905,an historic visit by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in 1913, theinterrogation of a Bahá’í at a police stationduring the Nazi regime, and the joyous con-secration of the Bahá’í House of Worship inLangenhain in 1964.

The September commemoration followedsignificant events in April and May that fo-

In Germany, Bahá’ís celebrate 100 yearsof crisis and achievement

cused on the outward relationships the Bahá’ícommunity has forged over the last 100 years.

On 10 May 2005, a centenary receptionwas held at the Berlin headquarters of thegovernment of Hesse, the state in which theHouse of Worship and the Bahá’í nationalcenter are located.

That reception was marked by a congratu-latory message from the German Minister forHome Affairs, Otto Schily, who praised thecontributions of German Bahá’ís in the pro-motion of social stability.

“The protection and preservation of com-mon values as well as the equality of all hu-man beings are basic principles of the Bahá’íFaith, and its adherents support them ac-tively in public discourse in Germany,” saidMr. Schily.

Mr. Schily said that Bahá’u’lláh’s “ex-tremely humane” principle guiding peopleto dedicate themselves to the service of theentire human race is valid for all the greatreligions of the world as well as for everycountry concerned with human beings andtheir rights.

“It is not enough to make a declarationof belief,” Mr. Schily said. “It is importantto live according to the basic values of our

Featuring prayers,

speeches, music,

and theatrical

performances, the

program took note

of the “dark” times

when the Bahá’í

Faith was banned

under Nazism —

and of the joyous

highlights that

have followed

during modern

Germany’s

reconstruction

and prosperity.

Among the performancesenjoyed by some 1,800participants gathered tocelebrate the 100thanniversary of the Bahá’íFaith in Germany were theseyoung dancers from theAnna Koestlin Schule.

ONE COUNTRY / July-September 2005 5

constitutional state, to defend them and makethem secure in the face of all opposition. Themembers of the Bahá’í Faith do this becauseof their faith and the way they see them-selves.”

Further, he said, in view of the inflam-matory slogans by some extremist groups, the2002 message of the Universal House of Jus-tice to the world’s religious leaders — whichcalled on them to act decisively to eradicatereligious intolerance and fanaticism — wasof great importance.

Together, Mr. Schily said, Germans mustabolish racial and ethnic prejudices and fightthe nationalism that incites hatred of othersrather than enriches the love of one’s country.

“I wish the Bahá’í community in Germanya peaceful and dignified future for their mem-bers but also, true to their own guiding prin-ciple, for all humankind,” he said.

The May program included a panel dis-cussion on the “Requirements of Social Co-hesion” that focused on social integrationand the role of religion in modern society.

In a keynote address introducing the dis-cussion, a prominent member of the Germanfederal parliament, Ernst Ulrich vonWeizsaecker, commended the ideas of the Ger-man Bahá’í community on social integration,which were published in a statement in 1998.

Other participants in the panel discus-sion included: the state secretary in the Fed-eral Ministry of Family Affairs, Senior Citi-zens, Women, and Youth, Marieluise Beck;the president of the Federal Agency of CivicEducation, Thomas Krueger; the plenipoten-tiary of the Council of the Protestant Churchof Germany to the Federal Republic and theEuropean Union, Stephan Reimers; and theacademic director of the Townshend Inter-national School in the Czech Republic,Friedo Zoelzer.

Among the invited guests were Buddhists,Christians, Hindus, Jews, and Muslims.

On 22 April, a reception was held at thenational Bahá’í center in Hofheim-Langenhain,next to the Bahá’í House of Worship.

Guests included representatives of theFederal and European Parliaments, the gov-ernment of Hesse, the cities of Hofheim andWiesbaden, and political parties.

At that reception, the state secretary of theMinistry of Science and Art of Hesse, Joachim-Felix Leonhard, praised the principles of theBahá’í Faith, describing the Bahá’í message as“cosmopolitan, global, and modern.”

“The Bahá’ís,” said Professor Leonhard,“are seeking to communicate and under-

stand at a time when others are talking abouta clash of civilizations.”

The mayor of Hofheim, Gisela Stang, re-ferred to initial opposition to the establish-ment of the House of Worship 41 years agobut said the Bahá’ís are now fully integratedinto the community.

“They provide an important impulse forthe city and for society,” said Ms. Stang, re-ferring to the forums the Bahá’ís organizeand to their cultural diversity.

Representing the city of Wiesbaden,Angelika Thiels thanked the Bahá’í commu-nity for its contribution towards nurturingunderstanding among religions. Ms. Thielsalso referred to the contribution of the Bahá’ícommunity in offering to the wider societyregular children’s classes in which pupilslearn about spiritual and moral values.

The September event was held in Stuttgartbecause that was where the German Bahá’ícommunity was first established, by EdwinFischer, a German-born dentist who emi-grated in 1878 from Germany to New York,became a Bahá’í there, and then returned tohis native country in 1905.

Dr. Fisher used every opportunity, in-cluding talking with his patients, to men-tion the Bahá’í teachings, and in time a num-ber of Germans embraced the new religion.

The community grew and in 1913‘Abdu’l-Bahá, the son of Bahá’u’lláh and the

The ups and downs of theGerman Bahá’í history,including an interrogation at apolice station during theprohibition of the Bahá’í Faithunder the Nazi-regime, werestaged by a group of Bahá’íyouth as part of centenarycelebrations in September.

“The protection

and preservation

of common values

as well as the

equality of all

human beings are

basic principles of

the Bahá’í Faith,

and its adherents

support them

actively in public

discourse in

Germany.”

— Otto Schily,

German Minister for

Home Affairs

ONE COUNTRY / July-September 20056

head of the Faith from 1892 to1921, visitedStuttgart. By 1923, the community hadformed the National Spiritual Assembly ofthe Bahá’ís of Germany, a national-level gov-erning council.

From 1937 to 1945 Bahá’í activities werebanned in Nazi Germany, in part because ofthe Faith’s progressive teachings, includingthe oneness of humanity. Local Bahá’í com-munities were dissolved and their literaturewas confiscated. Some of the believers wereinterrogated, imprisoned, and deported bythe authorities. Some Bahá’ís of Jewish back-ground were killed by the regime.

After World War II the German Bahá’í com-munity reestablished its activities. Help in thiseffort came, in part, from American Bahá’ís,who sent their German co-religionists money,food and literature, and aided them in rebuild-ing their administrative structures.

One of the featured guests at the Sep-tember commemoration was JohnEichenauer, a US soldier and a Bahá’í whohad been stationed in post-war Germany. Hetold participants of his experiences in help-ing the Bahá’í community of Germany re-build after the war.

By 1950, there were Bahá’ís living in 65localities in Germany. In 1964, the Bahá’íHouse of Worship in Hofheim-Langenhain

near Frankfurt was dedicated. Open topeople of all faiths, it is the first Bahá’í Houseof Worship on the European continent. In1987, the State of Hesse declared it a cul-tural monument.

With the political reunification of Ger-many in 1989, the Bahá’í community wassoon reestablished in eastern Germany.

Today, German Bahá’ís live in 900 townsand cities throughout the country. There are106 local Spiritual Assemblies, as local-levelBahá’í governing councils are known. TheBahá’í community is active in the discourseon interfaith and gender equality issues, aswell as in sustainable development and hu-man rights education.

At the September event, for example,Stuttgart’s deputy mayor for social affairs,Gabriele Mueller-Trimbusch, thankedBahá’ís for their initiative in starting WorldReligion Day.

“The respect you pay to other world re-ligions, your openness for people who havedifferent opinions, your message of peace forthe world we live in, makes you a greatlyappreciated partner for us,” she said.

“Stuttgart highly values the activities ofthe Bahá’í community, because it participatesin the social life of our city in an exemplarymanner,” Ms. Mueller-Trimbusch said.

NEW YORK — Dr. David S. Ruhe, formermember of the Universal House of Jus-

tice, the international governing council ofthe Bahá’í Faith, died on 6 September 2005near his home in Newburgh, New York, fol-lowing a stroke in mid-August. He was 91.

Dr. Ruhe became a Bahá’í in Philadel-phia in 1941, subsequently serving on nu-merous local Spiritual Assemblies and na-tional Bahá’í committees. Elected to the Na-tional Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís ofthe United States in 1959, he served as itssecretary from 1963 until 1968, when he waselected to the Universal House of Justice, onwhich he served until 1993.

A medical doctor, Dr. Ruhe was also anaccomplished film-maker, painter, and au-thor. Graduating from the Temple Univer-sity School of Medicine in 1941, Dr. Ruhebegan his medical career during World WarII as a malaria researcher with the UnitedStates Public Health Service.

In l954, Dr. Ruhe was named the first

professor of Medical Communications at theUniversity of Kansas Medical School. Amongthe innovations he introduced there were theuse of optical fibers for endoscopic cinema-tography, the projection of high-definitionimages in surgical theaters, and videotapingof psychiatric sessions for peer review. Hemade scores of medical films, winning theGolden Reel award, the Venice Film Festi-val award, and the Royal Photographic So-ciety of Great Britain award.

Dr. Ruhe was also prolific writer. In hismedical career, he authored many papersand two books on aspects of medicine andmedical audiovisual communication. Dur-ing his years at the Bahá’í World Centre, Dr.Ruhe wrote Door of Hope, a detailed historyof Bahá’í holy places in Israel, published in1983. Later, he wrote Robe of Light, a his-torical account of Bahá’u’lláh’s early years,published in 1994. Dr. Ruhe is survived byhis wife, Margaret, and two sons, Christo-pher and Douglas, and their families.

David S. Ruhe, former member of the Universal House ofJustice, passes away

Dr. David S. Ruhe

“The Bahá’ís are

seeking to

communicate and

understand at a

time when others

are talking about a

clash of

civilizations.”

— Joachim-Felix

Leonhard, state

secretary of the

Ministry of Science

and Art of Hesse

ONE COUNTRY / July-September 2005 7

NEW YORK — Persecution against theBahá’ís of Iran has continued to esca-

late in recent months, with fresh arrests inJuly, August, and September, and the arrivalof another school year in which Bahá’í stu-dents are denied access to university.

Some 23 Bahá’ís have been arrested sincethe end of June, bringing to 53 the totalnumber of Bahá’ís detained in Iran fromJanuary through September 2005. All wereheld on charges solely related to their reli-gious beliefs.

As well, hundreds of Bahá’í youth wereagain denied access to higher education thisyear when the Iranian government issueduniversity entrance examination results thatfalsely indicated they were Muslims, a movethe government first tried last year in a ployaimed at placating human rights monitorswhile still keeping Bahá’ís out of college.

“Between the rising tide of arbitrary arrestsand imprisonments and the continued sub-terfuge that prevents Bahá’í youth from ob-taining a college or university education, it isclear that Iran’s treatment of its Bahá’í minor-ity continues to worsen,” said Bani Dugal, theprincipal representative of the Bahá’í Interna-tional Community to the United Nations.

“We believe the degree of religious free-dom granted to Bahá’ís in Iran remains thelitmus test by which the Islamic Republic ofIran should be judged as the world looksfor signs of its willingness to behave as aresponsible member of the international com-munity of nations,” said Ms. Dugal.

Ms. Dugal said Bahá’ís were arrested inJuly, August and September in a number ofcities across Iran, including Mashhad, Karaj,Sari, Ghaem Shahr, and Babol Sar. Earlierin the year, Bahá’ís were arrested in Tehran,Kata, Semnan, and Shiraz.

“The pattern of arrests is widespread,clearly indicating the systematic nature ofthe persecution and the involvement of thenational government,” said Ms. Dugal.

Ms. Dugal said the pattern of arrests anddetentions has also been carried out with-out concern for due process. She noted, forexample, that on 5 September a court in Karaj

sentenced four Bahá’ís to ten months’ im-prisonment on the basis of a verbal indict-ment. “Those four, who had been releasedon bail on 15 August after business licenseshad been posted as collateral, asked for awritten document stating the charges againstthem, but the court refused to issue one,”said Ms. Dugal.

As well, Bahá’í homes continue to besearched, and documents and possessionsseized, said Ms. Dugal.

The continuing effort to keep Bahá’ís outof colleges and universities is in keepingwith a policy established in the late 1980s.

As last year, the government used a cruelploy to continue to deny Bahá’ís access tohigher education. Under pressure from theinternational community to allow Bahá’ís toreturn to university, the government in 2004and again this year allowed Bahá’ís to takenational entrance examinations.

However, as with last year, when exami-nation results were returned in August, thegovernment had printed the word Islam inthe field indicating the test-taker’s religion.Bahá’ís have long made it clear that as amatter of principle they will not falsely saythat they are Muslims — or allow themselvesto be falsely listed as Muslims.

This year, as well, Bahá’í students ap-proached the government and sought tohave the error corrected. And again, theywere rebuffed — and so as a matter of prin-ciple have refused to enroll.

“Given the government’s stated policy ofseeking to block the ‘progress and develop-ment’ of the Bahá’í community, as outlinedin a 1991 government memorandum, thislatest episode is clearly aimed at keepingBahá’ís out of college while placating hu-man rights monitors,” said Ms. Dugal.

“We have information that at least 200 Bahá’ístudents this year — and probably more —passed the examination and thus qualified forentrance into college,” said Ms. Dugal. “Butbecause the government continues to playgames over the very fundamental right to reli-gious belief, these young people are deniedaccess to higher education.”

H U M A N R I G H T S

In Iran, more arrests and another yearwithout college for Bahá’í youth

“This latest

episode is clearly

aimed at keeping

Bahá’ís out of

college while

placating human

rights monitors.”

– Bani Dugal, Bahá’í

International

Community

ONE COUNTRY / July-September 20058

U N I T E D N A T I O N S

UNITED NATIONS — World leaders re-newed their five-year-old promise to

halve global poverty rates, ensure educationfor all, and sharply reduce HIV/AIDS andother diseases — and also took new stepstowards reforming the United Nations — atthe 2005 World Summit in September.

Some 154 heads of state or governmentattended the Summit, held 14-16 Septemberto assess progress towards meeting the so-called Millennium Development Goals(MDGs), which were adopted at the Millen-nium Summit in 2000 and set global targetsfor reducing poverty and improving healthand education.

“We reaffirm our commitment to eradi-cate poverty and promote sustained eco-nomic growth, sustainable development, andglobal prosperity for all,” stated the outcomedocument, the final resolution adopted bythe General Assembly at the Summit’s end.

Also on the Summit’s agenda were pro-posals aimed at reforming the United Na-tions so as better to meet the needs of a glo-balizing world in which new and broadlyinterconnected problems — from terrorismto new diseases to poverty — increasinglythreaten international peace and security.

“We believe that today, more than ever be-fore, we live in a global and interdependentworld,” stated the outcome document. “NoState can stand wholly alone. We acknowledgethat collective security depends on effectivecooperation, in accordance with internationallaw, against transnational threats.”

World leaders took steps to adopt someof the reform measures that had been pro-posed in the lead-up to the Summit. Earlierin the year, for example, UN Secretary Gen-eral Kofi Annan released a report titled “InLarger Freedom” that called for the expan-sion of the Commission on Human Rightsinto a more broadly constituted HumanRights Council, urged the creation of an in-tergovernmental Peacebuilding Commission,and outlined steps to enlarge the SecurityCouncil to make it more representative.

The outcome document called for the cre-ation of a Human Rights Council, with theobjective of “promoting universal respect for

At the UN, world leaders renew promises

the protection of all human rights and funda-mental freedoms for all, without distinction ofany kind and in a fair and equal manner.”Decisions about “the mandate, modalities, func-tions, size, composition, membership, work-ing methods and procedures of the Council,”however, were handed to the 60th session ofthe General Assembly, which remains in ses-sion until next September.

World leaders also established aPeacebuilding Commission, with a mandate“to bring together all relevant actors to mar-shal resources and to advise on and proposeintegrated strategies for post-conflictpeacebuilding and recovery.”

However, plans to reform the SecurityCouncil were even less concrete. While theoutcome document states “we support earlyreform of the Security Council...in order tomake it more broadly representative, effi-cient, and transparent,” no definite propos-als were put forward.

Much of the outcome document restatedand reaffirmed the broad principles and com-mitments articulated in United Nations glo-bal conferences of the last decade.

“We reaffirm the universality, indivisibil-ity, interdependence, and interrelatedness ofall human rights,” world leaders said, echo-ing one of the most important elements ofthe Vienna Declaration of the 1993 WorldConference on Human Rights.

The outcome document likewise empha-sized the importance of full employment,sustainable development, and the idea that“progress for women is progress for all,”echoing key themes from the 1992 EarthSummit, the 1995 Social Summit, and the1995 Fourth World Conference for Women.

Where the 2005 Summit broke newground was, perhaps, in the broad articula-tion of the interconnections between the mainglobal challenges facing humanity.

“We acknowledge that peace and security,development, and human rights are the pillarsof the United Nations system and the founda-tions for collective security and well-being,”world leaders said. “We recognize that devel-opment, peace and security, and human rightsare interlinked and mutually reinforcing.”

“We acknowledge

that peace and

security,

development, and

human rights are

the pillars of the

United Nations

system and the

foundations for

collective security

and well-being.

We recognize that

development,

peace and

security, and

human rights are

interlinked and

mutually

reinforcing.”

— 2005 World

Summit outcome

document

ONE COUNTRY / July-September 2005 9

The program focuses on the preventionof alcohol and drug abuse, suicide, HIV/AIDS, and domestic violence. Since its found-ing in 1997, YCMTW has offered more than7,000 Guyanese young people strategiesaimed at helping them cope with and avoidsuch problems.

Its success at reaching youth on the mar-gins has been widely recognized, not onlyby other youth-oriented NGOs but also bythe government-run national university,which has given support to YCMTW. As well,much of its funding has come from interna-tional development agencies and, most re-cently, researchers at the University of Ulsterin Northern Ireland have launched a three-year study on the project’s methods and ac-complishments.

“The project in Guyana is quite innova-tive,” said Roy McConkey, a professor in thehealth promotion group at the Institute ofNursing Research at the University of Ul-ster, who is heading up the study. “Theymanage to do a remarkable amount of workwith very little resources.”

Established by the Varqa Foundation, aBahá’í-inspired non-governmental organiza-

tion based here, YCMTW also emphasizesin its training the importance of — and thepossibilities for — personal and communitytransformation. To do that, the project usesa program of spiritual and moral educationproduced by the Ruhi Institute of Colom-bia, which draws quite directly on the Bahá’íwritings for its motive power.

“From the very beginning of the project,we saw that the only way that genuinechange could come about was through com-munity and personal transformation,” saidBrian O’Toole, director of YCMTW andchairman of the Varqa Foundation. “We sawthat these Bahá’í materials were successfularound the world.”

Integrating spiritual valuesObservers say the emphasis on spiritual-

ity is an important part of the program.“The approach of integrating spiritual val-

ues, including positive community values,makes it a program with a difference,” saidSamuel A. Small, director of the Institute ofDistance and Continuing Education at theUniversity of Guyana, which provides end-of-training certification to YCMTW graduates.

“In the [other] youth programs that Iknow of and have participated in, spiritual

In Guyana, young people take the leadin an effort to avoid risky behaviors

Guyana, continued from page one

“The project in

Guyana is quite

innovative. They

manage to do a

remarkable

amount of work

with very little

resources.”

– Professor Roy

McConkey,

University of Ulster

Young people from aroundGuyana at a Youth CanMove the World facilitators’training session.

D E V E L O P M E N T

ONE COUNTRY / July-September 200510

values are never part of the core of the cur-riculum, and personally I believe that be-cause of the tremendous problems that arebeing brought upon young people today,every effort should be made to help them tosee that spiritual values are not taught sepa-rately in churches, mosques, temples and soon, but that they are really part and parcelof our every day life skills,” said Mr. Small.

The social problems addressed by theproject are by no means unique to Guyana— but they are nevertheless serious concernsin this beautiful tropical country situated onthe southern edge of the Caribbean basin.

After Haiti, Guyana has the highest HIV/AIDS rate in the Caribbean, which is theworld’s second-most afflicted region afterSub-Saharan Africa, according to the WorldHealth Organization. AIDS has become theleading cause of death for people aged 25-44 in Guyana, according to the WHO.

Domestic violence is also a major prob-lem. According to the International Women’sRights Action Watch, studies of domesticviolence in Guyana indicate that betweenone-third and one-half of all women faceincidents of domestic violence.

And, with high levels of unemployment,alcohol and drug abuse are also major prob-lems in Guyana, although few official statis-tics are available.

The program, which has received funding

from UNICEF, the European Union, and theInterAmerican Development Bank amongother agencies, seeks to fight these problemsmainly by educating young people about therisks associated with each behavior.

The facilitators’ manual, for example, dis-cusses the short and long term effects of al-cohol, ranging from poor judgment and low-ered inhibitions to cirrhosis of the liver anddependency. It explains clearly how HIV/AIDS is transmitted and discusses a range ofprotective measures, from less risky types ofsex to condom use to abstinence.

The curriculum also promotes the devel-opment of social action — such as the pro-tection of the environment — and positivemoral values. The section on domestic vio-lence, for example, explains ways in whichqualities like honesty, compromise, and for-giveness can improve a relationship.

Spiritual ideas, such as the Golden Rule,are also emphasized, underpinned by quo-tations from the major world religions.

“It comes out of a Bahá’í framework, butwe have enriched it with spiritual insightsfrom Islam, Christianity, and Hinduism,”said Dr. O’Toole, who came to Guyana withhis wife, Pamela, 27 years ago from theUnited Kingdom.

Addressing religious diversityThe incorporation of religious quotations

has resonated particularly well in Guyana,said Dr. O’Toole, owing to the distinctive re-ligious diversity of Guyanese society.

Colonized by the Dutch, who introducedAfrican slaves, the country later became aBritish colony. After a slave revolt and thesubsequent abolition of slavery, the Britishbrought in indentured servants from Indiato work on sugar plantations. At variouspoints, Portuguese and Chinese laborerswere also brought in.

The result today is an extremely diversesociety, composed of about 50 percent froman East Indian background, about 35 per-cent from an African background, about 7percent from a Native American back-ground, and the rest European, Chinese andmixed backgrounds. Religious beliefs are alsodiverse. About 50 percent of the populationare Christian, 35 percent are Hindu, 10 per-cent are Muslim, and the remaining fivepercent belong to other religions, includingthe Bahá’í Faith.

“One of the beautiful things aboutGuyana is that religion is very much a partof people’s lives,” said Dr. O’Toole of Varqa.

At the Future Club, YouthCan Move the Worldfacilitators led two dozenparticipants through adiscussion on suicideprevention, which ended withthe performance of variousskits to illustrate what hadbeen learned. At center isRayana Jaundoo, pretendingto drink Paraquat herbicideonly to have her friends snatchthe bottle away.

GUYANA

ONE COUNTRY / July-September 2005 11

“Even if they don’t practice it, they are in-terested in it.”

Young people who have participated inYCMTW training say the discussion of spiri-tuality is an important part of the program.

Susan Coocharan, 17, said the program’sbalance between practical education and theholy writings of various religions has givenher new tools to avoid risky behaviors.

“I used to think that guys were the onlything in life that matters,” said Ms. Coocharan,a Christian from Essequibo in the western partof the country, who participated in an inten-sive two-month YCMTW training program inJuly and August 2005. “But when I came tothis program it helped me to develop spiritualqualities and it made me see that guys are notthe only thing in life.”

Dhanpaul Jairam, 31, has been involvedin YCMTW since March 2005, when he re-ceived training to become a facilitator. AHindu, he has since established a YCMTWsubgroup in his home village of Bath Settle-ment in the Berbice region of Guyana, wherehe has reached out to young people fromevery religious background.

At first, he said, the Hindus didn’t wantto mix with the others. “But I talked aboutall of the religions,” said Mr. Jairam, whoworks as a radio telephone operator for theGuyana Sugar Corporation. “I do have aBible and a Qur’an. And Hindu writings.”

Because of the emphasis on all reli-gions, Mr. Jairam said, young people ofall backgrounds were willing to partici-pate. “That is why I think YCMTW is do-ing a great job of encouraging youth of allwalks of life to make of themselves some-body,” said Mr. Jairam.

Health promotion modelAnother key feature of the project is its

use of youth, themselves, as agents of change.By encouraging young volunteers to estab-lish YCMTW groups in their own villagesand neighborhoods, it has grown organicallyas young people themselves involve theirfriends and acquaintances.

Troy Benjamin, 19, started a 17-memberYCMTW group in his village in the remoteNorth Rupunui Region after attending theintensive training program last summer.

“I was very much interested, becausesome of the topics mentioned were dealingwith alcohol abuse, domestic violence, andsuch,” said Mr. Benjamin, who is himself ofNative American — or “Amerindian” back-ground — as are most of the other 500 resi-

dents of his village. “And I knew that thoseproblems were kind of arising, and I wasfacing it in my community as a whole.”

He said the young people in his grouplike the program. “Some of them actuallyhad these problems, and they were kind oftrying to get out of these kinds of problems,”said Mr. Benjamin. “The materials fromYCMTW [have] assisted me to carry outthese meetings.”

Prof. McConkey of the University of Ul-ster said using young people themselves to de-liver health promotion messages is one of thekey innovations of the project.

“In affluent countries like the UnitedStates and Great Britain, we rely on profes-sional educators, who may well have a spe-cial training or special expertise,” said Prof.McConkey. “But they may lack a relation-ship with young people. Hence we some-times wonder why our health promotionmessages don’t come through.

“The model that they are using, in whichlocal groups are built up, in which [young]people in those groups have knowledgeabout each other and their own behaviors— I think in that setting people are morelikely to be open about what they actuallydo,” said Prof. McConkey.

Over the next three years, Prof.McConkey hopes to study the degree towhich this and other features of the projectare effective in changing risky behaviors.

“I would think that there is a very goodchance that this will impact on the thoughtprocesses of the young people,” said Prof.McConkey, adding that, based on prelimi-nary interviews, “there is some evidence thattheir attitudes are already different.”

Mr. Small of the University of Guyana be-

Members of the Future Clubin Georgetown, at a YouthCan Move the World sessionon suicide prevention.

“I was very much

interested,

because some of

the topics

mentioned were

dealing with

alcohol abuse,

domestic

violence, and

such. I knew that

those problems

were kind of

arising, and I was

facing it in my

community as a

whole.”

— Troy Benjamin, 19,

Youth Can Move the

World facilitator

ONE COUNTRY / July-September 200512

lieves that program has already proven itselfto be highly effective. “I recall many positivestatements made by young people who havebeen through the program,” said Mr. Small.

He credits the program’s inclusiveness asone element of its success. “Every year I’vebeen surprised by the enthusiasm shown bythese young people,” said Mr. Small. “It at-tracts people across all ethnic, political, andreligious lines — the whole gamut.

“Another aspect of the program is the useof a variety of media to get across their mes-sage,” added Mr. Small. “There is drama,there is song and dance, there is poetry.”

At the YCMTW-led session at the FutureClub, the use of drama — in the form ofsimple skits about suicide — appeared to behighly effective, as did the idea of usingyouth themselves to deliver the message.

The Future Club is one of various youth-oriented groups and organizations — includ-ing schools — that have invited YCMTWfacilitators to make presentations.

The anti-suicide skit performed byRayana Jaundoo and other members of theClub was one of five such skits performedthat day after a presentation by YCMTW fa-cilitators about suicide.

All of the facilitators, who were youngpeople themselves, first talked about suicidein general terms, and then led the two-dozenparticipants through a series of true/false ques-

tions designed to explore some of the mythsand facts surrounding suicide. They also talkedabout contributing factors, such as isolation,drug and alcohol abuse, and domestic abuseor other problems in the home.

Kevin McPherson, 19, one of theYCMTW facilitators who led the session,received training about a year ago. Alreadya member of the Future Club — which itselfseeks to help teenagers develop greater self-esteem and self-confidence — Mr.McPherson said the YCMTW brings a dif-ferent approach to social awareness becauseit is young people talking to young people.

“It’s good for someone in your peer groupto stand up and say, “It’s wrong to beat yourwoman,” said Mr. McPherson, discussing theYCMTW message against domestic violence.

Lomeharshan Lall, 18, another of theYCMTW facilitators who led the session, saidhe believes the program has helped reachmany young people. “In Guyana, youth arebeing brought down by social issues, and soyou can rightly say that YCMTW is verybeneficial, because it has the answer to howto deal with these things,” he said.

Mr. Lall, known to his friends simply as“Lall,” knows of what he speaks. “Abuse anddomestic violence, drugs and alcohol, I’vewitnessed these things and that’s why I’minto this, because I know a lot of people whoare affected by it.”

The relationship between science and re-ligion is gathering increasing attention

around the world, from research about thepower of prayer to heal to the impact of newtechnologies on traditional societies.

Bahá’í scholars on two continents recentlygathered to explore the connection betweenscience and religion, among others issues,at regional conferences of the Association forBahá’í Studies.

In mid-August, the Association of Bahá’íStudies – North America met in Cambridge,Massachusetts, USA, on the theme of “Sci-ence, Religion, and Social Transformation.”

Attended by some 1,300 people, the 11-14August 2005 event explored everything fromthe role of inspiration in scientific discoveryto the value of prayer in healing. Presentationsranged from neuroscience and quantum me-chanics to philosophy and psychology.

In early July, the Association of Bahá’íStudies – English-Speaking Europe met inDublin to hear a wide range of papers ad-

Bahá’í scholars explore links between science and religion

dressing issues such as “Religious Belief andReproductive Technologies” and “Reflec-tions on Unity in Diversity.”

The 2-3 July event also featured a talkby Dr. Sheikh Shaheed Satardien, a Muslimcleric from the Dublin Inter-FaithRoundtable, who addressed the topic of re-ligious conflict.

At the North American conference, morethan 100 speakers presented during the four-day event. Participants came mainly from theUnited States and Canada but also traveledfrom Australia, Austria, Chile, China,France, Gabon, Germany, Haiti, Israel, Italy,Japan, New Zealand, Puerto Rico, Sudan,and the United Kingdom.

Most presentations focused on the mainconference theme. The Bahá’í sacred writ-ings explicitly uphold the underlying har-mony of science and religion, and manyscholars sought to show how these two sys-tems are increasingly seen as complemen-tary aspects of the same reality.

“The approach of

integrating

spiritual values,

including positive

community

values, makes it a

program with a

difference.”

— Samuel A. Small,

University of

Guyana

ONE COUNTRY / July-September 2005 13

H I S T O R Y

ELIOT, Maine, USA — According to somehistorians, the 1905 Russo-Japanese War

was the first truly modern war, involving asit did both the telegraph and the telephone,along with machine guns, barbed wire, illu-minating star shells, mine fields, advancedtorpedoes, and armored battleships.

The war’s resolution might also be calledthe world’s first modern “peace,” inasmuchas its end came about through perhaps thefirst use of so-called multi-track diplomacy,involving not only the belligerents but alsothe United States and, significantly, inputfrom civil society.

Were it not for US diplomacy and themilitary restraint displayed by the other Eu-ropean nations, the Russo-Japanese warmight have become the first world war. Forhis role in the so-called Portsmouth PeaceTreaty, US President Theodore Rooseveltwon the Nobel Peace Prize.

But it was the contribution of civil soci-ety, and in particular the activities of a far-sighted and influential woman — Sarah Jane

Farmer — that were honored in a commemo-ration here at the Green Acre Bahá’í Schoolin September 2005.

That commemoration drew the JapaneseAmbassador to the United States, who spokeat Green Acre on the topic of “Peace in the21st Century” on 4 September 2005. In par-ticular, the Honorable Ryozo Kato spokeabout Japan’s growing role in peacekeepingand peacebuilding efforts around the world.

“Japan is working around the world forthe conservation of the environment, for dis-armament, and for the eradication of pov-erty and disease,” said Ambassador Kato.

His speech, before some 175 people,capped a week of activities that celebratedthe role played 100 years ago by Ms. Farmer,who was an early member of the Bahá’í Faithin the United States and the founder of GreenAcre, which had established itself as a keymeeting point for leaders of nascent inter-faith and peace movements at the start of the20th century.

The Portsmouth Peace Treaty was signed

At Green Acre, the first “modern”peace treaty is commemorated

The event drew

the Japanese

Ambassador to

the United States,

who spoke at

Green Acre on the

topic of “Peace in

the 21st Century.”

Commemorating the 100thanniversary of the signing ofthe Portsmouth Peace Treatyand the role of Green Acrefounder Sarah Farmer insupporting it, celebrantscarried a peace flag inSeptember — along withflags of Japan, Russia, andthe United States.

ONE COUNTRY / July-September 200514

at the nearby Portsmouth Naval Shipyard,just down the Piscataqua River from GreenAcre. And at one point during the negotia-tions, diplomats could reportedly see a huge“peace” flag that was flown by Ms. Farmeron the grounds of Green Acre.

More importantly, Ms. Farmer had, in theyears preceding the Treaty negotiations,sponsored a well-known series of summerconferences about peace and inter-religiousharmony. [See book review on page 16.]

In 1904, for example, the annual GreenAcre conference closed with a program dedi-cated to the resolution of the Russo-Japa-nese war. The following year, when delega-tions from Russia and Japan were meetingin Portsmouth to negotiate an end to the war,Ms. Farmer obtained a pass to the ceremo-nial signing of the Treaty — the only womanto attend the event.

Charles Doleac, co-chair of the Ports-mouth Peace Treaty Anniversary Commit-tee, said at the 4 September commemorationthat Ms. Farmer and other early Bahá’ís inthe greater Portsmouth area played a criticalrole in pushing government delegations to-wards a settlement.

“The Bahá’ís in 1905 were really trying,through the work of Sarah Farmer, to re-solve this dispute,” said Mr. Doleac, who hasdone extensive research on the PortsmouthTreaty process and history.

Mr. Doleac added that other local civilsociety groups, including many churches inthe area, likewise pushed for peace, all help-ing to “create the atmosphere” that kept the

delegations at the negotiating table “untilpeace was achieved.”

Foad Katirai, who represented the NationalSpiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of Japan atthe event, said that the Portsmouth Peace Treatyprocess can be understood as among the first“multi-track” efforts at diplomacy, one thatincluded not only various governments butalso a civil society component.

“Many associations, many people, seekpeace,” said Dr. Katirai, who is also authorof a book, Global Governance and the LesserPeace. “The Bahá’í vision is perhaps uniquein that we regard world peace as alreadyhaving been born in the 20th century. Whatremains for us in the 21st century is to takethe newborn peace and to see that it growsand develops into a mature and lasting sys-tem of global governance.”

Erica Toussaint, a member of the NationalSpiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of theUnited States, noted in her remarks that‘Abdu’l-Bahá, the son of the Founder of theBahá’í Faith, had given a talk in Londonabout the prerequisites for universal peaceat about the same time as the PortsmouthTreaty was being signed.

“In that talk, he said: ‘In the days of oldan instinct for warfare was developed in thestruggle with wild animals; this is no longernecessary; nay, rather, co-operation andmutual understanding are seen to producethe greatest welfare of mankind,’ ” said Ms.Toussaint.

In his remarks, Ambassador Kato spokeof the close alliance between Japan and theUnited States in efforts to promote peace andfreedom around the world.

He said that today Japan is the world’ssecond largest democracy, second largestdonor of foreign aid, and second largest con-tributor to the United Nations.

Ambassador Kato also expressed “deep,deep admiration for the effort” that Bahá’íshave played in “attending to world peaceand human harmony.”

The week-long commemoration includeda talk by Suheil Bushrui, who holds theBahá’í Chair for World Peace at the Univer-sity of Maryland. On 26 August 2005, Dr.Bushrui spoke on “A Step Towards a Cul-ture of Peace: Reflections on the Treaty ofPortsmouth.”

Prof. Bushrui’s talk was followed by fivedays of diverse educational activities explor-ing the cultural, economic, educational,political, and spiritual foundations of thecreation of lasting peace.

Among the speakers at thecommemoration were, left toright, Erica Toussaint of theBahá’í community of theUnited States; theHonorable Ryozo Kato,Japan’s ambassador to theUnited States; and FoadKatirai of the Bahá’ícommunity of Japan.

“The Bahá’ís in

1905 were really

trying, through

the work of Sarah

Farmer, to resolve

this dispute.”

— Charles Doleac,

co-chair of the

Portsmouth Peace

Treaty Anniversary

Committee

ONE COUNTRY / July-September 2005 15

Restless SoulsReview, continued from page 16

nent religious and philosophical thinkers andactivists. They included Unitarian ministerEdward Everett Hale, women’s rights advocateMatilda Joslyn Gage, philosopher WilliamJames, Hindu guru Swami Vivekananda, Jainlecturer Virchand Gandhi, Buddhist monkAnagarika Dharmapala, and Black activistW.E.B. DuBois.

Dr. Schmidt focuses on Greenacre notonly because of its influence but also becauseof the way in which its history illustrates thetension that existed between religious plu-ralists who accepted everything and noth-ing at the same time, using universalism asthe justification for an endless individualis-tic quest, and those who, like Ms. Farmer,moved towards a more concrete expressionof faith, based on a new sources of authority,in a quest for genuine unity.

For Ms. Farmer, this occurred with herembrace of the Bahá’í Faith. She foundedGreenacre as a place in which all religioustraditions might be explored and individualspirituality pursued. But then a fateful en-counter aboard a ship bound for the Medi-terranean in 1900 led her to Palestine, whereshe met ‘Abdu’l-Bahá — and subsequentlydeclared herself a Bahá’í.

Upon her return, however, some acquain-tances criticized her conversion, saying Ms.Farmer had betrayed the principles of “self-reliant individuality and boundary-crossingcosmopolitanism” that had previously exem-plified the New Thought and related move-ments ensconced at Greenacre, a convertedinn on the pine-forested shores of thePiscataqua River.

“[P]eople were supposed to keep seek-ing, to remain open to new perspectives andinsights, not to settle on one path aloneamong many,” writes Dr. Schmidt.

But Ms. Farmer’s embrace of the Bahá’íFaith was “the culmination of her grand vi-sion of the unity of all religions.” In Ms.Farmer’s mind, Greenacre became “less aboutan open door than a final realization, lessabout a quest than a fulfillment.”

Dr. Schmidt notes that her “evangelism”as a Bahá’í was never “heavy-handed,” andthat a number of Greenacre seekers were alsohappy to embrace the Bahá’í Faith. Others,however, turned away, leading to a board-room battle for control of the place, whichMs. Farmer eventually won — although at

great cost to her peace of mind.Eventually, Greenacre became the Green

Acre Bahá’í School, which has remained com-mitted to the exploration of new religiousconcepts and principles, under the unify-ing vision of the Bahá’í Faith.

As an object lesson for today, however, thestory of Ms. Farmer and Greenacre — and in-deed the entire book — offers many parallelsto the kind of mixing and matching of reli-gious traditions that we see at a global level,and the accompanying concerns over author-ity and authenticity.

Recent international interfaith confer-ences, such as the 2000 Millennium WorldPeace Summit of Religious and SpiritualLeaders at the United Nations, or the revivedParliament of the World’s Religions in 1993,1999, and 2004, reveal a landscape of in-creasing religious tolerance, pluralism, anduniversalist patterns of thought.

For Bahá’ís, then as now, the foment inhumanity’s collective consciousness can beexplained as the spiritual influence that ac-companies the coming of a new Revelation.

The themes Dr. Schmidt traces as so emer-gent in liberal 19th century America — thecommonality of religious teachings, the needfor the independent investigation of truth,the breaking away from clergy, the equalityof women and men, the growing perceptionof unity in all things — are, in the Bahá’íview, obvious elements of the new spiritualreality that marks humanity’s entry into itslong promised age of maturity.

Those themes recur today as traditions andtraditional religious teachings are challengedby the forces of globalization, modernity, andindividual inspiration — forces which arethemselves understood by Bahá’ís to be theresult of the fulfillment of prophesies for anage of peace and enlightenment that are foundin all of the world’s great religions.

“A new life is, in this age, stirring withinall the peoples of the earth; and yet nonehath discovered its cause or perceived its mo-tive,” Bahá’u’lláh wrote in the mid-1800s.“It behoveth you to refresh and revive yoursouls through the gracious favors which inthis Divine, this soul-stirring Springtime arebeing showered upon you.”

Restless Souls is a book whose sum is morethan its parts. Interesting in its own rightfor the rich and complex picture it paints ofa time when Americans began to free them-selves from religious orthodoxy in a thou-sand different ways, it also holds up a mir-ror to our own time.

“Between its

founding in 1894

and Farmer’s death

in 1916, Greenacre

was among the

greatest sources

of religious

innovation

anywhere in the

country. It was

the last great

bastion of

Transcendentalism,

a school of

philosophy and art

for Emersonians

and Whitmanites;

it was a New

Thought proving

ground for such

leaders as Ralph

Waldo Trine, Henry

Wood, and Horatio

Dresser; it was a

hub for

representatives of

the Society of

Ethical Culture,

Theosophy,

Buddhism, Reform

Judaism, Vedanta,

Zoroastrianism,

Islam, and the

Bahá’í Faith.”

— Leigh Eric

Schmidt, Restless

Souls

ONE COUNTRY / July-September 200516

B O O K R E V I E W

Review, continued on page 15

Although it focuses on the American fas-cination with mysticism and churchless

spirituality in 19th century, many readers ofLeigh Eric Schmidt’s new book will un-doubtedly see parallels to trends and eventsin our own time, and on a global level.

Restless Souls: The Making of AmericanSpirituality is certainly fascinating enoughin its own right. Dr. Schmidt, a respectedprofessor of religion at Princeton University,charts the rise of religious pluralism and theshift from “old religions of authority” to“new religions of the spirit” in the UnitedStates, following a line that runs fromEmerson and Thoreau to the New Age spiri-tuality of television host Oprah Winfrey.

For Bahá’ís, moreover, the book is espe-cially significant because of the way it high-lights the impact and influence of SarahFarmer, the founder of what is today theGreen Acre Bahá’í School in Eliot, Maine.[See story on page 13.]

Dr. Schmidt devotes a whole chapter toMs. Farmer and Greenacre (as it was firstknown). As well, references to the influenceof Greenacre are salted throughout the book— it seems that almost everyone who wasanyone in the quest for enlightenment in theUnited States at the end of the 19th centuryspoke at or visited Greenacre.

The theme Dr. Schmidt develops over thecourse of the volume is straightforward. Ashe explains it: “This book probes the way inwhich the very development of ‘spirituality’in American culture was inextricably tied tothe rise and flourishing of liberal progres-sivism and a religious left.”

The discerning reader, however, is likelyto find another theme as well: how a great spiri-tual ferment in the 1900s, stirred by a widerange of new ideas, from transcendentalism totheosophy, and coupled especially with thedawning age of religious pluralism, openedthe door to a new acceptance of other religioustraditions by mainstream society.

As Dr. Schmidt writes, a “growing lib-eral fascination with a globalized mysticismof universal brotherhood” motivated and in-spired many of the leading religious think-ers of the late 1900s, culminating in eventssuch as the 1893 World’s Parliament of Reli-gions, as well as numerous books, lectures,

and pamphlets that explored the “perennialphilosophy” and the commonality of all re-ligions.

Certainly, this phenomenon is nowherebetter exemplified than in the story of Ms.Farmer and Greenacre, which is undoubt-edly why it occupies a central position inRestless Souls.

“Between its founding in 1894 andFarmer’s death in 1916, Greenacre was among

the greatest sources of religious innovationanywhere in the country,” writes Dr.Schmidt. “It was the last great bastion ofTranscendentalism, a school of philosophyand art for Emersonians and Whitmanites;it was a New Thought proving ground forsuch leaders as Ralph Waldo Trine, HenryWood, and Horatio Dresser; it was a hub forrepresentatives of the Society of Ethical Cul-ture, Theosophy, Buddhism, Reform Juda-ism, Vedanta, Zoroastrianism, Islam, and theBahá’í Faith.”

The list of those who populated Ms.Farmer’s circle and/or participated in the fa-mous Greenacre conferences of the late 1800sand early 1900s reads like a Who’s Who of promi-

Restless Souls:

The Making of

American

Spirituality

By Leigh Eric

Schmidt

Harper Collins

New York

A mirror to our own time