Anthony Beaver The Other Great Patriotic Warboinaslava.net/banshee1/The Other Great Patriotic...

Transcript of Anthony Beaver The Other Great Patriotic Warboinaslava.net/banshee1/The Other Great Patriotic...

Anthony Beaver

The Other Great Patriotic War

Russian America 1922-1947

Junograd University Press 2014

2

ANTHONY BEAVER is descended of a

long line of eccentrics who have served

in the armed forces of some nation or

other in various times and places

throughout history, most of them luck-

ily forgotten today. After quitting his

own career as an officer three months

into his term, he attended university for

ten years before achieving an M.A. in

politics and history. He has written ex-

tensively on obscure military topics to

compensate for his personal shortcom-

ings. Beaver lives in Berlin with his col-

lection of replica firearms.

Cover photo: Landing on Kiska, 1943

3

Contents

Preface 7

Introduction 8

Part I: The 1930s

Military Reforms prior to 1940 9

The Great Russian American Armed Forces Reform of 1940 10

Part II: 1942

The Road to War 13

The Japanese Attack 15

Early War Reorganisations 18

Part III: 1943

The Aleutians, Komandorskis and Iceland 21

Preparations for Kiska 26

The Debate on Operational Art 28

The Battle for Kiska 30

Lessons Learned 34

Overseas in America and Europe 36

Preparing for the Komandorskis 40

Part IV: 1944

The Two-Front War 45

Monte Cassino and Rome 47

The Raids on Attu 49

To the Komandorskis and Beyond 53

The Second Battle of the Komandorskis 55

Gold Beach 59

The Mid-1944 Plans 63

The Third Battle of the Komandorskis 67

Operation Dragoon 71

The Air Raids on Paramushir and Shumshu 74

4

The Retaking of Attu 77

The European Question Revisited 79

Dunkirk and the Scheldt 82

Deployment of II Corps 86

The Ardennes 88

Part V: 1945 in Europe

Operation Bodenplatte 93

The Reduction of Dunkirk 96

Yalta and the Soviet Prisoner Issue 100

Operation Varyag 105

Operations Amherst and Dykebreak 109

The Fight for Texel 112

To the Czechoslovakian Border 116

The Vlasov Dilemma 122

The Thrust onto Prague 125

Longboat and Battleaxe 128

The Cossack Problem 134

Redeployment from Europe 138

Part VI: 1945 in the Pacific

The Minor Allies Initiative 142

The Negotiations about an Allied North Pacific Command

Organisation 145

Operation Spud 149

Concentration on Japan 152

Allied Forces North Pacific Area 156

The Keychain Preparations 159

Operation Fencegate 163

The Island-hopping Plans 166

The Potsdam Conference 168

The Chinese Option 172

The Soviet Attack on Japan 176

Capitulation in the Kuriles 180

5

The Soviet Move onto Hokkaido 184

The Kurile Race 187

The Abashiri Incident 191

The Challenge at the Close 195

Part VII: After the War

The Drawdown Plans 201

Preparing for the Future 204

Pacts and Parades 209

Conclusion 212

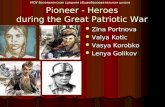

Illustrations

1. Location of major Russian American Army commands,

army troops and I Corps troops in May 1943 23

2. Location of major Russian American Navy commands

and ports in May 1943 24

3. Location of major Russian American Air Force commands,

air wings and airbase groups in May 1943 25

4. Revised unit patch of 1st Special Service Force 43

5. Location of major Russian American Air Force commands,

wings and airbase groups in December 1943 44

6. Planned assignments of Russian American forces to Allied

commands in January 1945 92

7. Location of Russian American units in the continental

European Theatre on 7 May 1945 121

8. Location of Russian American, US and Soviet ground forces

in the Okhotsk Theatre on 1 September 1945 199

9. Situation on northeastern Hokkaido on 1 September 1945 200

Appendices

A. 1940 Russian American Order of Battle 214

B. 1942 Russian American Order of Battle 218

C. Revised Rank Tables effective 1 January 1943 224

D. 1943 Russian American Order of Battle 226

E. The Aleutian Task Forces in 1943 233

6

F. Russian Contingent Allied Forces Atlantic in 1943 236

G. 1944 Russian American Order of Battle 238

H. Russian American Type 1944a Division 246

I. The Aleutian Task Forces in 1944 262

J. The Light Task Force 264

K. 1945 Russian American Order of Battle + Homeguard 265

L. The Russian American-Czechoslovakian Battlegroups 277

M. Russian American 1st Airborne Brigade in Europe 278

N. Russian Contingent Allied Forces Southwest Pacific 283

O. Russian American Forces in Europe on 7 May 1945 284

P. The Berlin Memorandum of 9 August 1945 286

Q. Allied Forces North Pacific Area 287

R. Allied Order of Battle for Operation FENCEGATE 293

S. Allied Order of Battle on Hokkaido on 31 August 1945 295

T. 1946 Russian American Order of Battle 299

Abbreviations 308

Bibliography 310

7

To most of the world today, Russian America is a remote nation on the edge of the Arctic, best

known as a destination for those who want to spend a vacation not just off the beaten track, but

indeed off any unbeaten tracks, too – an image reinforced by recent “reality” TV shows featur-

ing crab fishers in the Aleutian Islands or modern-day gold diggers following in the footsteps

of the 19th century Klondike gold rush. To Canadians and US Americans, it is of course a close

neighbour and trade partner, the traditional main export business of wood long since displaced

by oil and natural gas in top importance. Quite surprisingly, other than king crabs, Alaska

salmon and other fish, its most acknowledged contribution to international cuisine is beer.

Yet even the origins of the famous Stoyanka Pilsener are intricately linked to the country’s

tumultuous past of the pre-World War Two era, as brewing there was started by refugees from

German-occupied Czechoslovakia. The important role Russian America played in the war, all

the while performing a delicate act of balancing its own interests with those of its far larger

allies, seems often forgotten these days. As far as it is covered in popular entertainment, you

could be excused for believing Hollywood that fighting there was done essentially by US

troops, and over US territory, too. It is even rarer for the Russian American contributions in

the European Theatre to be mentioned by non-domestic productions, the 1968 film “The

Devil’s Brigade” being among the few exceptions.

It is therefore quite fortunate that the recent debate among historians about the failed 1867

negotiations between Imperial Russia and the United States over a purchase of the former’s

then-colony by the latter – notably Cab in “Unintended Consequences” and Kirk in “A Long

Story” – has generated some interest in the country’s history that also allowed this book to be

created. One can but speculate what course events would have taken if what has since become

known as “Seward’s Folly” had not occurred. Of course the opinion of the US secretary of state

at that time, William Seward – albeit formed under the pressure of a critical public – that the

inhospitable land was not worth the millions of dollars demanded by the Russian government

was only shown to be wrong ex post with the successive discovery of large deposits of gold

and other natural riches, up to the oil and gas of the later 20th century.

The intention of this book however is not to add to this discussion by investigating “what

ifs”, but rather explore the history that followed from the point at which Russian America in-

deed – though quite unwillingly by either side – parted ways with the empire it had belonged

to. The nature of the era as well as the author’s interest and expertise mandate that this will

focus on military developments and the conduct of World War II including the immediate post-

war period; though I hope that in due time and if my publishers see the value of it, I will cover

Russian American history to the present day in subsequent volumes.

There is a relative dearth of English sources on this topic so far, which may explain the pre-

vious sparse treatment it has received by authors not capable of the Russian language such as

myself. However, as a result of the same history portrayed in this book, there is no shortage of

helpful Russian Americans whose knowledge of English would put some native speakers to

shame. I can impossibly name all those who assisted me in my endeavour and without which

this work could not have been created; some I cannot name at all.

However, I want to particularly thank the staff at the Junograd Military Archives who worked

tirelessly to find crucial documents and translate them, too. I am also indebted to the Russian

American Duma and State Council Library for providing other domestic sources; and the Tan-

ski Foundation which usually prefers to stay out of the public light, but nonetheless afforded

me with certain services and comforts which made my undertaking very much easier.

Anthony Beaver

Junograd, 3 August 2014

8

Introduction

After the end of the Russian Civil War, the Provisional Russian-American Government that had

formed in the erstwhile North American colony of the Russian Empire following the successive

defeat of the earlier governments under Kerensky, Kolchak, Semyonov, the Merkulovs and

Diterikhs by the Bolsheviks in the motherland was faced with a difficult situation. While the Red

forces had little means of advancing across the Bering Strait nor much influence among the local

population which consisted overwhelmingly of refugees from their rule, the latter presented their

own problem.

The population of Russian America before World War I had been a mere 200,000 – two thirds of

them deportees under the katorga system, another fifth non-Russian immigrants, mostly Americans

and Canadians who had stayed after the Klondike Gold Rush or were trading in fur and wood

despite the strict imperial immigration policies. During the years of the Civil War, about a million

Russian citizens fled the violence and revolutionary furore to the colony despite the rugged condi-

tions there, many hoping they would eventually return home.1

Instead, refugees from the newly established Soviet Union and émigrés who had previously gone

into exile in Europe, the United States or elsewhere kept migrating to the only part of their home-

land that could be considered a reasonable approximation of free compared to the USSR, even

though it was at this point little more than a military dictatorship itself. While the great natural

riches of Russian America were known even then, the newcomers were disproportionately city

dwellers of white-collar persuasions, academics and aristocrats who had little enthusiasm to work

in fishing, hunting, logging and mining.

More practically-minded folks from Canada, the US and even Japan and China gladly seized

upon the business opportunities arising from the rapidly expanding population of their neighbour

country, but the first decade was troublesome despite, and sometimes because, of their addition.

Besides economic and social problems, the situation across the Bering Strait remained tense.

Though both sides were determined to eventually vanquish the other and reunite the former empire

under their rule, both lacked the means for decisive action.

Upon evacuating from the Siberian Far East, the White forces had taken most of the Pacific Fleet's

remaining ships with the help of the Entente intervention troops, but could not hope to return vic-

toriously against the existing odds. On the other hand, Russian America continued to enjoy the

support of the Entente powers which recognised theirs as the legitimate Russian government rather

than the Bolsheviks in Moscow. In the absence of a distinct strategic advantage for either side, both

engaged in small-scale military action and clandestine warfare.2

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, there was a succession of minor skirmishes at sea and coastal

raids which accomplished little, mostly around the opposing shores of the Bering Strait and the

Aleutians, Komandorskis and other islands in between that were controlled by Russian American

forces. Both sides ran campaigns of agitation, sedition and sabotage against the other, in addition

to White undercover networks helping Soviet citizens escape the USSR. Yet numbers seemed to

favour the latter, since with the Soviet drive for industrialisation it was only a matter of time until

the Red Army would gain the technical means to bring its overwhelming superiority to bear.

1 Cab, M.: Unintended Consequences. The History of Russian America, Vol. 1 (New Orleans 2012), p. 1-66. 2 Kirk, T.: A Long Story. How an American Folly Saved Russian Democracy, Vol. 1 (Durango 2011), p. 3-163.

Part I: The 1930s

9

Part I: The 1930s

Military Reforms prior to 1940

Prior to World War I, Russian America had been garrisoned mostly by the Imperial Navy. This

included a squadron of modern Novik class destroyers, but the only other combatants were six

older gunboats which were backed up by some armed icebreakers and other auxiliaries. On shore,

there was a regiment of marines and the fortifications at the regional naval headquarters in Novo-

arkhangelsk as well as the ports at Kodiak and Unalaska, manned by coastal artillery personnel.

Like all of the Pacific Fleet, the Great War saw a relocation of forces to the European Theatre,

though the comparatively weak numbers and small vessels of the empire's remote American out-

post meant it would contribute little to that draft.

As the tide of the Civil War turned against the White forces, strength was bolstered greatly not

only by the aforementioned Navy ships evacuating from Eastern Siberia, but also refugees from all

other fleets. Most famous was of course Wrangel's Fleet which made its way from the Black Sea

and formed the bulk of the new Russian American Navy. However, the service saw its importance

dwindled by the far greater influx of Army personnel. In 1922, about 60,000 soldiers had congre-

gated in Russian America, compared to just 30,000 sailors. In either service, there was a dispro-

portionate number of officers, particularly generals. This state of affairs could not possibly be sus-

tained by the troubled, still sparsely populated country.

Some effort was made throughout the first decade of its existence to organise the excessive,

widely disparate forces, armed with a motley collection of weapons both built in Russia and pro-

cured from abroad during World War I. By 1932, a system of conscription had been enacted that

required all male citizens to serve two years in the Navy or the Army regiments that had been

formed according to the shifting demographics in the main areas of settlement. The second Russian

American census of that year showed more than a doubling of the Russian population from 1.16

million in 1922 to 2.43 million, the bulk not having settled in the rugged Panhandle area around

the capital of Junograd, but around the rapidly growing economic centre of Stoyanka.3

At this point there was a total of 32 Army regiments – 18 infantry, seven artillery, five cavalry

and two engineer – as well as three port, two marine and two coastal artillery regiments of the

Navy. The regiments generally had only one active battalion with two more in reserve. The Army

was organised into one cavalry and four “square” infantry divisions. Some regiments were being

converted to modern arms that would support the divisions upon mobilisation. 3rd Kenai and 12th

Stoyanka Artillery were being turned into anti-air units, while 2nd Matanuska-Susitna Infantry was

planned to become an armour unit equipped mostly with Vickers Six-Ton tanks.

The Navy had a cruiser squadron of three old and run-down protected cruisers that were in urgent

need of replacement. Further there were three destroyer squadrons and one squadron of gunboats,

submarines and auxiliaries each, plus two reserve transport squadrons. Its flagship was the battle-

ship General Alekseyev from Wrangel's Fleet, and the former unprotected cruiser Almaz was serv-

ing as a training vessel. Like the Army, the Navy operated a small but diverse collection of aircraft,

some single examples of their type. There was no independent air force.4

That would change with the great Russian American Armed Forces Reform of 1940. Throughout

the 1930s, the military had sent observers – some not quite passive ones – to the armed conflicts

3 Russian American Census Bureau: 1932 National Census Data (Junograd 1933). 4 von Sieben, S. W.: Minutiae of War Ministry Plans Department Meetings 1938-1945 (Junograd Military Archives),

79-106.

Part I: The 1930s

10

of the time between Japan and China, to the Spanish Civil War, the early German operations of

World War II and the Winter War in Finland, in order to keep abreast of technological and opera-

tional developments. Ideology played a role, too, as Russian American volunteers fought against

communist forces in Spain and Finland.

This resulted in relations with Germany that were altogether too close for the liking of Russia's

former Entente partners. Neither was it domestically uncontested, particularly after the German

invasion of Czechoslovakia; senior officers who had fought alongside the Czech Legions in the

Civil War took offence at the government's silence on this attack on their former comrades, and

even channelled refugees from the occupied country to Russian America – notably General Sergei

Nicolaevich Vojcechovski.5 Fortunately for the greater picture, the Hitler-Stalin Pact of 1939 and

the subsequent joint German-Soviet invasion of Poland led to a rift in German-Russian relations,

and despite German designs to keep Russian America as a North American ally in the upcoming

World War, the country would eventually end up on the Allied side through circumstances.

The Great Russian American Armed Forces Reform of 1940

It was not before 1936 that a comprehensive attempt at modernisation involving both traditional

services as well as the creation of a Russian American Air Force on the British and German model

started. It encompassed both organisation and equipment as well as the build-up of domestic arms

production capabilities. The bottom-up approach started with the procurement of new small arms

and extended to the order of four new “patrol cruisers” from US yards – really destroyer leaders,

somewhat glorified to placate the Navy which was having a difficult time of playing second fiddle

to the land forces in its former American fiefdom.

The initial two Kolchak-class vessels were designed with both Russian and American interests

in mind, as they allowed US shipbuilders to construct large destroyer-type combatants for a cus-

tomer that was not under the tonnage limits of the 1930 London Naval Treaty, and thereby explore

designs better suited to Pacific ranges. Somewhat of an intermediate step between the US Navy's

Porter- and Somers-class destroyers and the later Atlanta-class anti-air cruisers, the Kolchaks in-

troduced the famous 5”/38 Mk 12 gun into the Russian American Navy when they were commis-

sioned in 1938/39. Three were planned originally, but instead they were supplemented in 1940/41

by two half-sisters of the Nakhimov class which replaced the four Mk 22 low-angle twin mounts

and two Mk 21 high-angle single mounts with four Mk 29 dual-purpose twin mounts.

The Navy was also an early customer for the Bofors 40 mm and Oerlikon 20 mm anti-air guns,

unlike their American counterpart which went with the less successful 1.1”/75 gun at this time. The

new light, medium and heavy AA guns also found themselves in the modernisation of battleship

General Alekseyev done in US yards during the same period despite misgivings in Junograd about

the material and personnel resources this single capital ship was tying up in the Navy. But in the

end, the 1940 Fleet Plan included Alekseyev as well as a squadron with the new cruisers, three with

destroyers including three Clemson-class four-stackers transferred from the US, a gunboat squad-

ron and a squadron of eight submarines built by Elco on the basis of their S-class, replacing the

outright dangerous World War I models. Three transport, two auxiliary and a minesweeper squad-

ron made up the rest of the fleet, much of them in reserve status.6

5 Tuček, M.: Eastward. Russian American-Czechoslovakian Military Cooperation in the European Theatre of World

War II (Junograd-London-Versailles 1954), p. 8. 6 von Sieben, 108-121

Part I: The 1930s

11

Like the Army, the Navy gave up some of their aviation personnel to form the new Air Force,

though proportionally less so. After trials with shipboard spotter planes largely failed due to the

prevalent Russian American weather conditions, they embraced large flying boats. This led to a

fruitful cooperation with early Russian emigrant Igor Sikorsky who had already become a US cit-

izen at this time, but after recent economic fiascos was faced with the threat of having his company

merged with the Vought division of the United Aircraft Corporation which had bought it in 1929.

The Russian American government saved him by not only buying 30 of his S-44 flying boats which

had lost out to the Consolidated Coronado in the US Navy's PB2Y competition, Sikorsky's largest

sale so far; they also established Sikorsky Aircraft Stoyanka, a 50:50 public-private partnership

which formed the seed of a domestic aircraft production.7

The fledgling Air Force took over most of the other existing aircraft, a motley collection of pre-

dominantly light transport and trainer aircraft like the Tiger Moth, Northrop Delta and Fokker Su-

per Universal – less than 30 total, since the Army retained a squadron of Avro 504s and some

Pitcairn-Cierva autogyros for spotting and liaison purposes. Like their British and German role

models, they also became responsible for strategic ground-based air defence, resulting in most of

the heavy anti-air artillery being transferred from the Army. First orders of new aircraft included

the Curtiss Hawk Model 75 fighter and Douglas Model 8 attack aircraft as well as some DC-3

transport planes.

The plans for buildup of the Air Force were quite ambitious considering circumstances, and en-

visioned seven new airfields to be constructed in addition to the only existing ones at Baranov,

Stoyanka and Krasivayaberga – the latter little more than open fields used by pilots flying along

the Baranov-Stoyanka-Krasivayaberga railway line. The future bases were however intended to

have hard-surface runways, and help from Canada and the US was enlisted to build them. Consid-

ering local weather conditions and the time needed to train pilots, the programme was supposed to

last until the end of the 1943 warm period.

At this point, eight Air Force wings were to be established, six comprising a fighter and attack

squadron each, two with transport and training aircraft. Most would be based along the southern

coast and the near Aleutians, with one in the north at Nome on the Bering Strait and the transport

wings in Stoyanka and Krasivayaberga. Each wing would also command an airbase and an anti-air

group, with extra ones at Kenai, the planned government airport at Junograd and a staging airfield

en route to Nome at Makkrazky.

The necessary ground personnel was to be freed mostly by the disbanding of four Army infantry

regiments. Accordingly, an infantry division was struck from the 1940 Army order of battle. These

divisions were quite unwieldy, typically so for a country with no contemporary experience in mod-

ern large-scale land warfare. Each had two brigades of two infantry or cavalry regiments each, an

artillery regiment of three light and one medium battalion, a quartermaster battalion, an HQ and a

signals company. Upon mobilisation, an armour, engineer, anti-air, medical and military police

battalion each would be attached along with an additional cavalry squadron. Army troops also in-

cluded 1st Guards Regiment in Junograd, 1st Northern Yeger in the Arctic North, 11th Stoyanka

Heavy Artillery and 5th Krasivayaberga Heavy Engineer Regiment.8

The greatest change however happened in equipment at unit level. The rimmed 7.62 x 54 mm

round used in the old Mosin-Nagant rifles and Maxim machine guns was to be replaced by a mod-

ern rimless cartridge along with the variously-chambered mix of light machine guns. The choice

eventually fell on the American .30-06 calibre, which would not only be fired from the new air-

craft's guns but also the future standard infantry weapons, also made in the US: The Enfield M1917

7 Sikorsky Aircraft Stoyanka: A Semi-Century of Excellence (Stoyanka 1989), p. 7. 8 von Sieben, 122-206.

Part I: The 1930s

12

rifle, the Lewis light machine gun and Browning M1919 medium machine gun. In replacement of

various handguns like the Nagant M1895 revolver and American-imported Colt M1911 pistols and

M1917 revolvers, the FN M1935 pistol was chosen as the new service sidearm. The Finnish KP-

31 was introduced as the first standardised submachine gun, though some Thompson M1928 had

found their way from the US earlier.9

Successors to the World War I-era artillery guns of mostly British make were also sought, as

were modern light anti-air and anti-tank guns and infantry mortars. However, world events, politi-

cal infighting, corruption and inter-service rivalry proved of much hindrance in acquisition. The

Czech TNHP tank had already been chosen as the follow-on for the Vickers Six-Ton when the

German occupation of that country and subsequent breakdown of relations with the Third Reich

sent procurers scrambling in search of alternate sources after delivery of only a battalion's worth.

Similiar things happend after the fall of Belgium, and it was not before production of the FN Hi-

Power pistol at Inglis in Canada was in full swing in 1943 that the older handguns were beginning

to be fully replaced.10

Czech refugees were instrumental in establishing arms manufacturer Russkaya-Boheme Zavod

in Stoyanka which would eventually become the chief domestic source of automatic weapons and

artillery guns – but not before at one point the Kutuzov Navy Arsenal at Novoarkhangelsk was

raided by marines on direct orders from the Ministry of War to find dozens of Czech-licensed guns

stashed away in its casemates.11 Many coastal artillery pieces turned out to only exist on paper, and

the old 130 mm guns of General Alekseyev mysteriously vanished after her refit with 5”/38

mounts.12

A centrepiece of the 1940 reform was the motorisation effort due to the difficult Russian Ameri-

can conditions for horses; the rugged terrain and lack of grasslands made the logistics for fuel easier

than feeding the animals. Despite tradition, the cavalry was first to be equipped with motor vehicles

except for a Cossack squadron doing ceremonial duty at the government seat, along with the artil-

lery. The infantry took longest, but retired their last horses and mules in 1942 except for some

doing duty with 1st Northern Yeger.13 Nothing however proved quite as controversial as the re-

placement of the soldiers' traditional footwraps with Western-style socks, bitterly opposed by tra-

ditionally-minded senior officers.

9 von Sieben, 110-113. 10 von Sieben, 118-121. 11 von Sieben, 143. 12 von Sieben, 245-255. 13 Kentukski, R. R.: The Russian American Cavalry (Stoyanka 1961), p. 16.

Part II: 1942

13

Part II: 1942

The Road to War

The reforms proved not an outright success, and continuous changes were made throughout the

next two years after the nominal implementation date. Only after the inter-service conference of

February 1942 the Russian American order of battle solidified into a form that would remain rec-

ognizable for the coming years as war loomed on the horizon, in no small part influenced by reports

of the battles that were already being fought outside the country.

The Army underwent probably the most extensive corrections as it went to a separation between

frontline and territorial tasks. Its wartime organisation now foresaw I Russian American Army

Corps as its operational arm and Territorial Army Command for administrative and home defence

purposes. With most units mobilisation-dependent, both major commands were run in peacetime

by deputies to the Chief of the Army who had shifted headquarters from Junograd to Stoyanka,

closer to the bulk of his forces.

The divisions in I Corps had been further reduced to three, now of mixed triangular structure with

one cavalry and two infantry regiments supported by an artillery regiment and anti-air, armour,

engineer, medical and quartermaster battalions, now permanently assigned. Only 1st Division was

fully active, while 2nd and 3rd had less than ten percent of their wartime establishment of 15,600

present in peacetime, mainly fulfilling territorial tasks in lieu of inactive Territorial Army units.

Corps troops included semi-active 5th Krasivayaberga Heavy Engineer and 11th Stoyanka Heavy

Artillery as well as a reserve quartermaster regiment and signals battalion, plus an army aviation

unit variously termed a company or squadron in different documents which was already planned

to test the brand-new Sikorsky R-4 helicopter as a supplement to its Pitcairn-Cierva autogyros.

The reduction to three divisions was mostly a result of the new Air Force's need for personnel to

support its rapid growth, and had been arrived at by way of three-and-a-half, at different times

proposed to include an independent cavalry or even airborne brigade. Airborne trials had been

conducted at battalion level, but manning constraints prevented the establishment of such a cutting-

edge unit, and the prospective paratroopers eventually found themselves folded back into 1st Divi-

sion's infantry. Regiments had to be streamlined too, and the infantry lost its organic engineer com-

panies which were found to contribute nothing that the divisional engineer battalions did not, too.

The Territorial Army was organised into five regional commands, most with an infantry regiment

that would serve as a training and replacement unit for I Corps in wartime as well as in home

defence, and also a signals, quartermaster and military police battalion each, plus a military hospi-

tal. With the exception of the semi-present MP battalions which also fulfilled civilian police tasks

in the thinly-populated rural areas outside the towns and cities, all those were inactive in peacetime.

Central Command, responsible for the population centre of the Stoyanka region, was unique in

having two infantry regiments and MP battalions each, as well as a full quartermaster regiment.

Territorial Army Command also administered the Central Military Court and Prison in Stoyanka.

Army troops consisted of 1st Guards and 1st Yeger Regiment as before, while an extra cavalry

regiment had been elevated to the status of 7th Guards Cossack Regiment, serving as a parent unit

to the previous single Cossack squadron in Junograd. The cavalry was still divided into light and

heavy squadrons, the former mostly equipped with motorbikes and some Canadian-made Fox var-

iants of the Humber armoured scout car, the latter in the process of replacing their Vickers light

tanks with the American M3 Stuart in addition to M2 halftracks.14

14 von Sieben, 135-243.

Part II: 1942

14

The issue of the Stuart was however under a cloud of doubt both due to political circumstances

and the still-lacking number of tanks because of the protracted search for an alternative to the

TNHP. The American M3 Lee was considered less than optimal chiefly due to its armament layout.

This left the Canadian Ram and Swedish LAGO as main contenders.15 In the end the Ram won out

because it was being built close by, but the initial difficulties Canada had with establishing produc-

tion led to considerations of redirecting Stuart deliveries to tank units.16

Things looked better on the artillery side were RBZ was now building Czech designs at its

Stoyanka plant in addition to acquiring licenses for the Bofors and Oerlikon anti-air guns. Old

howitzers and cannon were steadily being replaced by domestically produced pieces except for

previously-ordered things like the Böhler 47 mm infantry/anti-tank gun and American 60 and 81

mm infantry mortars. RBZ was also looking into new light machine guns and submachine guns.

The Army had some interest in self-loading rifles, though this had so far only resulted in some

demonstrations of the American Johnson M1941 family of infantry weapons.

Army HQ was supported by a semi-present signals regiment, with the Army School Command

directly subordinated as well. Centralizing technical and leadership training which had previously

been conducted mostly within the regiments revealed an imminent lack of cadre for the new mo-

bilisation-dependent structure; despite of the abundance of officers in 1922, 20 years later most

had gone into civilian life, many were too old to be recalled to active duty in wartime, and some

had died off. To address this, plans for reserve officer and non-commissioned officer training were

drawn up, whereby promising conscripts would be sent to NCO school, and the best of those on to

take officer candidate classes. Overall, mobilised strength of the Army would come out to 110,800,

with only 30,700 active in peacetime. This included a number of 2,700 respectively 1,100 female

auxiliaries who mostly served as nurses and in HQ and signals units.17

The Navy was now similarly divided into a Naval Operations and a Coastal Command. The for-

mer included Strike Fleet that had lost its old gunboats, transferred to the coastal artillery and

moored as floating batteries at remote ports like Nome and Nikolskoye on Bering Island. Also there

were now only two, but larger destroyer squadrons, one to be fully made up of Clemsons delivered

by the US as replacements for the older Noviks in a scheme similar to the Ships-for-Bases Deal

with Britain. This agreement not only allowed US Army Air Force units to be stationed on the

South Coast to look out for Japanese forces following the attack on Pearl Harbor in December

1941, but also Lend-Lease aid for the USSR to be transported across Russian America and the

Bering Strait after the German attack on the Soviets.

For obvious reasons, this had been a difficult agreement, since the Junograd government was not

at all keen to see military equipment being passed to their arch enemy through their own territory.

However, Allied pressure had been immense and backed up by implicit military threats over Rus-

sian America's earlier close relations with Germany; obviously neither the US nor Canada were

going to allow a possible pro-Axis base at their back. In the end, Junograd also saw the opportunity

to profit of the same pipeline and assented under the condition they would also get American ma-

terièl – naturally not in the same quantity, but if possible of later models than for the Bolshevists.

The Naval Operations Command also included Auxiliary Fleet which had mostly reserve units

except for an auxiliary squadron as before, and Naval Aviation Command with three squadrons of

the new Sikorsky S-44 flying boats, one of which reserve. The shore-based units found themselves

15 Engelsen, T.: Slick Swedish Salesmen. Swedish-Russian American Arms Procurement Relations since 1936 (Ber-

gen 2012), p. 10-13. 16 Colins, C.: Canucks in the Aleutian Islands. As Canadian Military Attaché in Russian America during World War

II (Vancouver 1960), p. 9-10. 17 von Sieben, 225-240.

Part II: 1942

15

under Coastal Command which was again divided in three regional commands at Novoarkhan-

gelsk, Kodiak and Unalaska. Those led the port battalions, navy training and replacement regi-

ments, two coastal artillery and two or three marine battalions each, the latter mostly inactive in

peacetime. Once more the centrally-situated Kodiak Command was larger than the rest since it also

administered the ports of Stoyanka and Baranov, and had two training regiments. The overall mo-

bilised strength of the Navy was set at 49,400, 22,800 in peacetime with 1,200 and 500 female

auxiliaries respectively.

As the junior service, the Air Force was at this point still led by a three-star rather than a four-

star general and had a single layer of higher commands, regionally orientated much like the Navy's

with Central Command headquartered in Stoyanka, Eastern Command at Junograd and Western

Command at Kodiak. Each had one basic training and three operational wings, though semi-present

3rd Wing at the new Junograd government airport had no flying squadrons and 6th Wing at Yakutat

on the “panhandle joint” was a reserve unit. There was also independent 5th Anti-Air Artillery

Group in Kenai under Central Command. Mobilised strength was just 26,900 with 16,700 in peace-

time, including 500 and 400 female auxiliaries respectively.18

However, the Air Force stood to profit most from the Lend-Lease agreement with the Americans,

since the latter were very interested to build up a network of bases for aircraft delivery along the

trans-Russian American route across the Bering Strait. As a result of massive US help, the planned

airfields were finished a year ahead of schedule, and additionally staging bases were built subse-

quently. The deal also opened the way for more modern aircraft. The Lockheed P-38 Lighting was

considered the ideal fighter for Russian American needs due to its long endurance, while the Doug-

las A-20 was planned to replace the Douglas Model 8 attack bomber. Three wings were to be

reequipped in the course of the year.19

Negotiations were still somewhat rocky as Junograd had chosen to stay on the sidelines after the

Japanese raid onto Pearl Harbor despite US and British pressure to join the Allied side in the new

World War. However, since the earlier German attack on the USSR had already brought Moscow

into that camp, neither Russian party was prepared to fight on the same side even with the Lend-

Lease agreement in place. Cooperation was limited to the establishment of a heavily surveilled

Soviet mission in Nome which would take over aircraft from US – rarely Russian – personnel for

the flight across the Bering Strait. The USSR also honoured its non-aggression pact with Japan,

while Junograd feared the Japanese would come north after being done with European possessions

in Southeast Asia and the Pacific. There was the gloomy thought that the Empire of the Rising Sun

might eventually make the decision for Russian America, which turned out to be quite right.20

The Japanese Attack

The 1942 order of battle was to be evaluated in the spring exercises of May that year, a series of

complex problems lasting three weeks. The first week was a full mobilisation drill for I Corps, all

army troops and select units from Territorial Army, as well as part of the Navy's Auxiliary Fleet

and Coastal Command, and all Air Force units. While 2nd and 3rd Division mobilised along with

Territorial Army HQ, signals, quartermaster and medical units in Central, Northern and Southern

Command and all of Western Command, 1st Division was to undertake an embarkation exercise

with 1st Sealift Squadron, reinforced by 4th and 7th Marine Battalion.

18 von Sieben, 245-262. 19 Nikitin, D.: Knocking on Wood. Russian American Military Procurement in World War II (Junograd 1975), p. 14. 20 von Sieben, 134-268.

Part II: 1942

16

Simultaneously, Strike Fleet conducted manoeuvres in the Gulf of Alaska including submarine

and aviation exercises. The Air Force was running mock anti-shipping missions, and USAAF units

newly based on the southern coast and the near Aleutians under the Ships-for-Bases deal partici-

pated as air-to-air sparring partners. After meeting up with the troop convoy out of Stoyanka, the

Navy started an escort operation leading into an amphibious landing west of Stoyanka including

minesweeping exercises, gunnery exercises by 2nd and 5th Coastal Artillery Battalion, and a live

fire shore bombardment exercise prior to landing on the northern shore of the Cook Inlet. At this

point, 2nd and 3rd Division were expected to be fully mobilised and oppose the landing under I

Corps HQ along with corps troops, reinforced by 1st Yeger and 7th Cossack Regiments.

At the same time in week two, 1st Guards and 2nd Northern Infantry Regiment along with 1st

and 4th Coastal Artillery Battalion and Air Force Eastern Command were training the defence of

the Panhandle and Junograd against the other six Marine battalions landed by 2nd Sealift Squadron.

On 15 May, the opposing forces in the Stoyanka area were to unite under I Corps HQ with the

objective to take an unnamed Russian-speaking port on the Pacific played by Stoyanka, though the

problem made it sound suspiciously like Vladivostok. The four activated territorial regiments were

to play defence, each representing an enemy division.

In reality, the exercises revealed severe shortcomings, probably exacerbated by the long delay in

establishing the final 1942 OOB and the corresponding short time troops had had to adapt. But

there was also a lack of training and specialised equipment. A deficit in anti-submarine capabilities

was highlighted when “enemy” submarines “sank” General Alekseyev and some of the troop trans-

ports and escorts, which had to be administratively revived for the next phase to take place. A good

portion of reservists never showed up or came in late for mobilisation, their units deploying at 70-

90 percent strength – though more due to communication and travel breakdowns than ill will.

Whole battalions had not yet received their new jeeps or Czech guns; 3rd Tank Battalion had no

tanks at all, but showed good initiative and was still able to field a very diverse reduced company

of vehicles stolen from neighbouring units.

Several soldiers drowned in the landings, and two tanks were lost along with several other vehi-

cles when one of the pioneer ferries used to land heavy equipment capsized. Fortunately for the

invaders, the defenders were late in getting to the beach, and opposition was only met after the first

wave had already formed ashore. The problem of manning with reservists was even more obvious

in territorial regiments and specifically extended to cadres; in the defence of Stoyanka against I

Corps, many companies were operating with only half their officer and senior non-commissioned

officer establishment, though they ultimately performed no worse than the attackers.21

Air Force pilots showed a particular lack of experience in mock fights with the Americans, though

the use of older Hawk and heavy P-38 fighters against the more agile USAAF P-40 may also have

contributed to negative results. A significant portion of the A-20 attack aircraft suffered engine

problems on long flights, resulting in one crash landing at sea. The Air Force subsequently in-

creased maintenance training, but also went to look for an overall more reliable plane; the de Havil-

land Mosquito had already generated interest due to its good reputation in Canada and the ease

with which its wooden airframe could possibly even be produced domestically. It was also recom-

mended that rather than replacing all Hawks by twin-engine fighters, a long-range single-engine

aircraft should be looked for, though none was available in the current political climate.22

The latter was about to change though, as the Japanese, alarmed by the basing agreement with

the US, were already moving against the Russian American islands. American intelligence had

21 von Sieben, 273-288. 22 Grushchev, O. D.: Reports on Aircraft and Aircraft Production Trials 1940-1948 (Junograd Military Archives),

197-290.

Part II: 1942

17

been aware of this for some time from decrypted radio signals, but even while USAAF planes were

searching heavily for the expected IJN battlegroup, Washington chose not to inform the govern-

ment in Junograd which had still not entered into an official alliance. Considerations of forcing the

issue may have played a part in this decision. Even so, the situation was nervous enough; in the

middle of the spring exercises, a Russian American flying boat had already used live depth charges

against a possible Japanese submarine reported by a Canadian aircraft off Ketchikan to inconclu-

sive results.23

In the end, another Navy patrol aircraft spotted the Japanese carrier group 800 nautical miles

southwest of Unalaska on 2 June anyway, but soon lost it in bad weather.24 The government in

Junograd inquired with the Japanese ambassador, who however feigned ignorance and promised

to check with Tokyo. He then returned to the Government Palace in the dead of night to hand over

Japan's declaration of war over the basing agreement immediately before aircraft from carriers

Junyō and Ryūjō attacked Unalaska Naval Base, quite similar to the playbook for the Pearl Harbor

attack.25

The first air raid by about 20 planes was ill-coordinated, again due to weather conditions, and

they were driven off by AA fire and fighters from nearby Umnak Air Base with little damage to

either side.26 A stronger and better-timed attack on the next day was more successful, with the oil

storage, radio station, hospital and a barracks ship being hit, though the base remained operational.

The Japanese were then again lost in bad weather before any decisive action could be taken against

the battlegroup. They showed up again on 6 June when they started occupying the Aleutian islands

of Kiska and Attu as well as the Komandorskis against little resistance, only Bering Island having

had a meaningful Russian American garrison.27

The Junograd government was now faced with open Japanese aggression, but had few means for

an effective response in light of the results from the recent exercises; the bulk of forces had cer-

tainly proven to be neither personally nor materially equipped for successful amphibious operations

against a competent enemy, the main benefit being that mobilisation was now well-rehearsed as

the armed forces went to full war footing. Naval and air action was the only one possible to be

taken immediately, and over the next months, Russian American submarines were the only units

to score successes to be appropriately celebrated by an initially shocked public. Okun sank a Japa-

nese destroyer and heavily damaged another one off Kiska on 5 July, and ten days later Sardina

sank two subchasers and damaged a third in the same port.28

During the same time, the Air Force bombed Kiska twice in concert with the Americans who

now had five fighter and six bomber squadrons in theatre, but while a Japanese oiler was sunk in

port, losses were more evenly distributed in the skies. On the political front Germany had quickly

followed the Japanese declaration of war, which made the course ahead obvious; within days after

the Unalaska attack, Russian America signed the Declaration of the United Nations, thus making

its joining the Allies official.29

The most important result of the now-clear fronts was that the faucet of US material aid was

turned wide open, including the promise of such highly advanced systems as the radar-equipped P-

70 night fighter variant of the A-20 and surface search radars for ships and aircraft of the Navy –

23 von Sieben, 287-302. 24 Russian American Admiralty: Dispatches 1942-1945 (Junograd Military Archives), 2 June 1942. 25 von Sieben, 302. 26 Admiralty, 3 June 1942. 27 von Sieben, 308-323. 28 Admiralty, 5 and 15 July 1942. 29 von Sieben, 323-333.

Part II: 1942

18

not least in view of typical Russian American weather conditions.30 Canada also offered to con-

tribute to the joint defence of the North American continent within its means, deploying RCAF

squadrons and RCN vessels as well as a ground contingent to secure Ketchikan Air Base against

air raids.31

Early War Reorganisations

Attempts to rectify the structural shortcomings of the armed forces started quickly while aiming

for a long game. The most immediate worry was however that the occupation of the Komandorskis

and far Aleutians was a either a prelude to an island-hopping campaign towards the mainland or a

screening action for landings on Soviet Kamchatka which might also involve the taking of Nome

on the Bering Strait, based upon US intelligence estimates and alleged sightings of Japanese ships

near St. Lawrence Island. The Navy went in search of the reported contacts, Strike Fleet mainly

hunting ghost ships north of the Aleutians in the first months, while 3rd Division was deployed to

the West Coast along the Yukon River together with the reserve squadrons of 6th Air Force Wing

to the not-yet garrisoned Nome airfield, in order to defend against an invasion that ultimately never

came.

With a wartime draft in place, all services were to be strengthened to retake the occupied islands

the next year, hoping that rugged conditions, local weather and long supply lines coupled with

naval blockade operations and frequent air raids would attrit the Japanese garrisons over the long

Russian American winter. Increasing numbers proved to be not so much a problem of available

conscripts, nor of enthusiast volunteers of any age and both sexes, but of the cadre to lead them.

The reserve officer and NCO training schemes already thought of were sped up in implementation

along with a rank reform that went with a thorough cutting of leadership posts at unit level.

Since NCOs could be trained more quickly than officers and territorial units had proven to operate

just as well with less cadre personnel, this concerned mostly officers; company XOs were deleted

as were assistant platoon leaders, half to two thirds of platoons now led by NCOs like the German

army was already doing for similar reasons. Praporshchiks en route to reserve officer rank after

completing platoon leader course could take this role too, or act as company sergeants. Promising

NCOs were also sent to take officer classes.

Overall, a third of officer and a sixth of NCO post were deleted in infantry regiments, along with

about 30 enlisted positions deemed “unproductive”, mostly orderlies; the Type 1943 Division

shrunk by about 750 to 14,841 all ranks. This was to pay not only for staffing of activated reserve

units, but the establishment of additional ones, too. Two new territorial regiments were stood up

for home defence, but also in view of possibly reforming previously-disbanded 4th Division. In

addition, personnel who had participated in the airborne trials were used to form the core of an

airborne regiment after all. School Command was expanded due to greater requirements, and the

equivalent of a full Military Police Battalion formed under the Central Military Court and Prison

to deal with possible higher numbers of POWs. Additionally, the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps

was expanded and occupations in the territorial quartermaster units opened to its members. Overall,

the planned 1943 Army OOB foresaw a strength of 116,500, including 3,600 female auxiliaries.

There was a renewed interest interest in automatic rifles to counter the expected greater numbers

of the enemy; since American Garands were not available due to domestic US demand, an order

for Johnson M1941 rifles and light machine guns was placed, intended to equip the guards, marines

30 Bergmann, P. G.: Reports to the Air Force Headquarters 1940-1945 (Junograd Military Archives), 351. 31 Colins, p. 17-18.

Part II: 1942

19

and yegers first. The new airborne force was impressed by a prototype Johnson carbine that would

eventually be produced as the M1943. In Stoyanka, RBZ was trialing belt-fed infantry machine

guns influenced by the German MG 34 that had been encountered by observers in Europe, but for

now put the finishing touches on their M42 which was quite similar to the Czech-British Bren.

There was less concern about enemy armour, though the British Six-Pounder anti-tank gun was

planned to be introduced due to ammunition commonality with the Ram Mk II tank which was

finally beginning to arrive. The American “Bazooka” was also being looked at, but had no priority.

The divisional artillery regiments were assuming a new organisation of two light howitzer battal-

ions equipped with the 100 mm M39, one medium howitzer battalion with the 149 mm K4, and a

cannon battalion with the 105 mm M35, with US-delivered halftracks as prime movers.

The other services saw similar developments. The Navy was to expand its single minesweeper

squadron of drafted fishing trawlers refitted with minesweeping gear to three with dedicated Ca-

nadian-built Isles-class vessels to prepare for the expected mine threat in amphibious landing. The

marine and coastal artillery battalions were expanded and again consolidated into regiments, one

under each regional command, to counter possible further landings. Surface combatants were to be

equipped not only with radar, but increased light anti-air artillery of 20 and 40 mm calibre, follow-

ing Allied experience in earlier naval operations.

Modern American “K-Gun” depth charge projectors were also to be installed during refits in US

yards, and the remaining 18” torpedo tubes on old Russian destroyers swapped to standardize on

the 21” calibre on American-built ships. The Navy had unfortunately lost two of its eight subma-

rines early on already – Sardina probably sunk by the Japanese and the class lead boat Skumbrii

run aground in foggy conditions while recharging batteries – and was looking for replacements.

The total planned 1943 strength for the Navy was 56,200, including 2,200 female auxiliaries in

shore occupations.32

The Air Force was still growing the most rapidly and expected to stand up two additional wings,

13th at Nome and 14th at the Aleutian island of Adak where the Americans were already building

a new airfield closer to the enemy. Another was planned even farther out at Amchitka, and the 1943

Air Force OOB made provision to establish at least a basic air base group there to handle forward-

deployed aircraft detachments. Similiar groups encompassing maintenance, supply and some anti-

air units were stood up for the quickly-emerging staging airfields on the Lend-Lease routes, five to

be operational until the end of 1943. The Air Force found joint US-Russian bases particularly val-

uable, as their personnel could profit from the experience of the Americans, and even attached

pilots to USAAF and RCAF units to learn.

New US-delivered P-38E and A-20C made up for losses in early air combat – though pilots were

not as easily replaced – and the first P-70 night fighters to equip two squadrons were also promised

for later in the year. At this point however an agreement had already been struck with de Havilland

to build their Mosquito domestically, with most parts other than the wooden airframes to be sourced

from Canada. Initially three light bomber squadrons were to be equipped, though long-term plans

extended to fighter-bomber and night fighter variants, too.33 The P-51 Mustang had piqued interest

as a possible new single-engine long-range fighter despite some performance shortcomings of early

models used by the British RAF, but was not thought to be available quickly.34 For the moment,

improving fighter performance concentrated on RBZ modifying the unreliable American variant

of the Hispano 20 mm cannon of the P-38.35

32 von Sieben, 352-373. 33 Grushchev, 305. 34 Nikitin, p. 16. 35 Bergmann, 334.

Part II: 1942

20

In light of the new airborne regiment, airlift capacities were to be increased to three C-47 squad-

rons, the older light transport planes to be distributed to the wings as liaison aircraft. Needful of

personnel to support its growth but still considered the junior service, the Air Force was first to

employ women in other than staff and medical roles, using them as shuttle pilots to transfer planes

delivered from the US to Ketchikan in the far South of the Panhandle like the Americans and British

did, too – though at first on an individual basis rather than in organised units. The 1943 Air Force

OOB called for a total strength of 36,000, including 1,500 female auxiliaries.

Meanwhile, the Japanese had shown no intention of progressing beyond the islands they had

already captured. 3rd Division was living in largely dismal conditions on the undeveloped arctic

West Coast, initially often in tents and holes in the ground until engineers from 5th Krasivayaberga

Regiment pulled somewhat rustic, but complete bases from the soil in place. Classic war diseases

were common at the start, and by autumn, some units reported up to 20 percent of personnel down,

including through a minor localised cholera epidemic. Along with solid quarters, better supplies, a

stepped-up training on nutrition, personal and collective hygiene and health education, backed up

by on-site inspections by senior medical officers, eventual fixed the problems. 3rd Division com-

mander Lebed used the time on deployment to develop and train his troops in a concept of mobile

defence using combined-arms battlegroups similar to the American regimental combat teams.

However, the perceived inaction of the bulk of Russian American forces led to discontent both at

home and among the Allies who were starting to ask if a division or so might be deployed to the

European War Theatre if troops lacked the training and equipment to engage the Japanese at their

doorstep. Domestic worries included the mobilisation of a total of 13 percent of the male population

(and 0.5 percent of the female) under the plans for 1943, and the impact on the civilian economy.

Wartime rationing had been implemented and was projected to support the population until the end

of 1944, but there were no guarantees the war would be finished by then. Again, this apprehension

turned out to be correct.36

36 von Sieben, 335-373.

Part III: 1943

21

Part III: 1943

The Aleutians, Komandorskis and Iceland

In the absence of means for decisive large-scale operations against the invaders, the Russian Amer-

icans did what they knew best, because they had done it for the last two decades: propaganda and

clandestine warfare. Most of this was obviously not carried out by the regular armed forces, but

the Signal Corps, as the innocuous designation for the Russian American intelligence service went.

Signals had initially focussed on espionage, sedition and sabotage operations against the USSR

as well as counterintelligence efforts against similar enemy actions. In addition, it was running

most of the state-sponsored underground networks that helped escapees from communist rule get

to Russian America. As Soviet influence on world affairs grew, so did the scope of Signals' activity:

watching the armed conflicts in China, Spain and Finland and acquiring new military technology

as a clandestine supplement to the open presence of military observers and volunteers. The mission

of increasing the Russian American population soon expanded from helping escapees to recruiting

Soviet POWs from Finland in quiet agreement with the Helsinki government and, after the break

with Germany, refugees from occupied Eastern Europe – mostly Czechoslovaks and Yugoslavians

– as well as Jews from Western Europe in collaboration with the Zionist Organisation.

The propaganda effort included newsreels of commando operations against the Japanese in con-

cert with troops from the Aleutian and Komandorski garrisons cast as keeping up resistance against

the invaders. In reality, activity on the occupied islands amounted to little more than covered re-

connaissance by Signals' small paramilitary arm, the “Signals Escort Battalion”. Most footage of

heroic fights with the enemy was shot in thoroughly unoccupied places, the Japanese soldiers por-

trayed by Russian American residents of Asian descent, possibly backed up by some actual Japa-

nese POWs or even KIAs. In support, a series of movies was commissioned by the armed forces

which depicted valiant commandoes, airmen and sailors fighting the enemy in the Aleutians.37

Meanwhile actual efforts of ground forces were centred on acquiring and training with amphibi-

ous craft. Since Allied priority for delivery to this theatre was low, a deal was negotiated with the

US for Higgins Boats and larger types to be built in Russian American shipyards, but it would take

time before a sufficient number was ready. There were also plans for actual raids in the Aleutians,

Komandorskis or even Kuriles; some in Junograd saw the retaking of the latter, lost to Japan in the

19th century, as an eventual war aim anyway. One rather fantastic variant from the Navy called for

a reduced battalion of marines to be landed by flying boats. An even more high-stake scheme was

to propose a counter-invasion in the largely uninhabited Central Kurils to the Americans, depend-

ant on the latter's considerable material support – expected to be denied for being too aggressive,

thus winning more time from Allied demands for substantial contributions to the war effort.

The sea and air remained the main fronts though. In September 1942, the new airfield on Adak

became operational, and on 12 January 1943, a joint American-Russian force landed on Amchitka

to begin construction of another base. Unfortunately destroyer Schastlivy ran aground and sank

with loss of 14 lives during the operation, but things for the Air Force looked up. The first crews

for the new P-70 night fighters had finished training, and domestic production of Mosquito bomb-

ers begun. Even the Mustang fighter had come into reach as the Americans were about to switch

production to the P-51B, and a surplus run of the A variant was promised for delivery in March.38

37 Tanski, S. S. (ed.): The Pocket Book of Declassified World War II Signal Corps Documents (Stoyanka 1986), p.

13-20. 38 von Sieben, 381.

Part III: 1943

22

The Amchitka base was finished shortly before that, and at this time battleship General Ale-

kseyev, escorted by two destroyers southwest of Attu, also chanced upon a Japanese cargo ship that

failed the radio challenge, was shelled and blew up with no survivors found, likely having laden

ammunition. Alekseyev then continued towards the Komandorskis with cruiser Kolchak and De-

stroyer Division 11 under Commander Strike Fleet, Admiral Nemzov, to search for other expected

Japanese supply convoys. On 27 March, the formation indeed found a transport group escorted by

heavy cruisers Nachi and Maya, light cruisers Abukuma and Tama as well as four destroyers.39

In the ensueing First Battle of the Komandorskis, Alekseyev crippled Nachi who was subse-

quently sunk by Maya after taking her crew off, but was herself hit by a torpedo fired by a destroyer

screening the stricken cruiser.40 She stayed afloat but had her screws and rudders wrecked and aft

engine room flooded from the detonation under her stern. Unable to manoeuver, the rest of the

Japanese escaped her group, and she had to be precariously towed to Unalaska. There she was

found to be not worth to repair since she would have spent months in drydock, tying down resources

urgently needed to build landing craft, and spent the rest of the war as a floating battery in port.41

While the sinking of a heavy Japanese cruiser received appropriate Allied applause, the opera-

tional loss of Alekseyev actually increased dependency on US support, and in the one area where

Russian America had its own national effort going to boot. There were negotiations about a possible

replacement by one or two American light cruisers, but the hope for a damaged US Navy vessel to

be transferred after repair never materialised. Another suggestion was to take over a light aircraft

carrier, which was considered seriously enough for the Air Force to send some pilots to train for

carrier operations with the USN; but that, too, was not to be at this point.42 Instead, the Americans

deployed their own task force of cruisers and destroyers to the theatre.

Under this state of affairs, Junograd could no longer deny Allied requests for a Russian American

contribution in the European Theatre, though a division was considered an all too open-ended com-

mitment. Brigade-sized offers for the Mediterranean or arctic-trained troops to be based in the UK

for raids into Norway were evaluated. But in the end, a rather unexpected proposal to defend Ice-

land and Greenland was settled upon by all involved. Negotiations with the American and Icelandic

governments resulted in a contingent of 13,500 troops in total, mostly taken from 2nd Division;

three regimental groups were formed from 1st Matanuska-Susitna Infantry, 1st Kenai Infantry and

2nd Kenai Cavalry with elements of the division's engineer and medical battalions, augmented by

two artillery groups from IV./3rd Kenai Artillery and 2nd Anti-Air Battalion, II./5th Krasivay-

aberga Heavy Engineer Battalion, 2nd Quartermaster Battalion and companies from 4th Military

Police Battalion. Additionally, II./1st Northern Yeger Battalion was to be based in Greenland.

In essence therefore most of a division was sent after all, though the North Atlantic basing was

deemed acceptable. Some equipment was to be brought along across the Gulf of Alaska, the width

of Canada and the Atlantic; some would be taken over on Iceland, some directly delivered there

new from US production. Ultimately the deployment also proved a convenient maskirovka for the

preparations of offensive operations in the Aleutians which had been made by now.43

39 Nemzov, K. A.: Battle at the Komandorski Islands (Junograd 1956), p. 20. 40 Admiralty, 27 March 1943. 41 Nemzov, p. 395-437. 42 Bergmann, 439. 43 von Sieben, 398-440.

Part III: 1943

23

Fig

. 1:

Loca

tion

of

majo

r R

uss

ian

Am

eric

an

Arm

y c

om

man

ds,

arm

y t

roop

s an

d I

Corp

s tr

oop

s in

May 1

943

.

Part III: 1943

24

Fig

. 2:

Loca

tion

of

majo

r R

uss

ian

Am

eric

an

Navy c

om

man

ds

an

d p

ort

s in

May 1

943

.

Part III: 1943

25

Fig

. 3:

Loca

tion

of

majo

r R

uss

ian

Am

eric

an

Air

Forc

e co

mm

an

ds,

air

win

gs

an

d a

irb

ase

gro

up

s in

May 1

943

.

Part III: 1943

26

Preparations for Kiska

Simultaneously with the debate on European deployments, the plans for a first reconquest of occu-

pied Russian American territory from the Japanese took shape. They centred on the Aleutian island

of Kiska, since it was the closest, smallest and easiest terrain-wise. Intelligence estimates about

strength of the enemy garrisons had initially been in the regimental range for each island, then later

revised upwards to possibly one of the IJA's independent mixed brigades each, suggesting up to

9,000 personnel including naval and air detachments. Still, reconnaissance missions by the Signals

Corps indicated Kiska was more lightly manned by a regimental group.

Timing was crucial. The conventional campaign period under local weather conditions was from

May to September, with June to August preferable. On the other hand, more time meant more of

the new landing craft ready and troops trained in their use. It was clear from the outset that the bulk

of forces would come from 1st Division which was the most capable one, having been active before

the war and gotten some – if unfortunate – experience with amphibious landings in the 1942 spring

exercises. They would be supported by marines who were trained in landing with conventional

boats, but lacked heavy firepower from divisional support weapons. 3rd Division was still deployed

to the West Coast, while 2nd Division would eventually form the Iceland contingent.

The first draft for the Kiska ground combat element, designated 1st Aleutian Task Force

(Ground), called for three battlegroups following the concept developed by 3rd Division to spear-

head the landings. They would be formed from two battalions of 1st Stoyanka Infantry, 1st and 2nd

Marines respectively, reinforced by the regimental cannon companies and one light and heavy

squadron from 5th Stoyanka Cavalry each. 2nd Stoyanka Infantry and the rest of 1st Division's

troops would follow in their conventional order once the beachheads were established.

I./1st Yeger Battalion was also assigned to the task force, and in the course of the negotiations

about mutual Allied contributions, the US and Canada offered their joint 1st Special Service Force.

This small elite brigade had been stood up for attacks on high-value targets in German-occupied

Norway which never materialised in favour of long-range bombing missions, but was ideally suited

to the Aleutians with its arctic and mountain training. Overall, the first draft for 1st ATF (G) called

for a strength of 20,000. This was found too unwieldy and quickly divided into two echelons, 1st

ATF now consisting of the three battlegroups, 1st SSF and some supporting elements with a total

strength of 13,800 for the landings, and a 2nd Aleutian Task Force (Ground) uniting the follow-up

formations for a total of 6,700 personnel.44

For the naval side, the Aleutian Joint Allied Naval Task Force was established. It commanded

three task groups led by Russian America, the US and Canada respectively. The Landing Force

was entirely Russian with two transport and two minesweeper squadrons, protected by the Kolchak

cruiser division and a destroyer squadron, and supported by an auxiliary squadron. The bulk of

firepower for naval gunfire support was provided by the all-American Covering Force consisting

of heavy cruisers USS Indianapolis, Louisville and Salt Lake City, light cruiser USS St. Louis and

three old Omaha-class CLs, as well as another destroyer squadron. The Screening force was Cana-

dian led with anti-air cruiser HMCS Prince Robert as flagship, two Tribal-class destroyers and five

River-class frigates; the Nakhimov cruiser division and 3rd Naval Aviation Squadron were also

attached from the Russian American Navy.45

Air support was provided by the Air Force's Central Command which was reinforced to five

wings for the operation, including the two night fighter squadrons that were planned to transfer

from the P-70 to the incoming Mosquito NF Mk XII until then – the former planned to replace lost

44 von Sieben, 418-428. 45 Colins, p. 21-22.

Part III: 1943

27

A-20s in the attack squadrons, modified for the night anti-shipping role – and the first squadron

flying the P-51A. In addition, Eleventh US Air Force would bring its 28th Bombardment Group

with three B-24D and B-25C squadrons each, as well as 343rd Fighter Group with another six

squadrons, two of which Canadian. The Americans also planned to deploy 407th Bombardment

Groups with four squadrons of A-24 dive bombers; however, the existing airfields in the Aleutians

were already at the edge of their capacity with current aircraft in theatre.46

To relief the strain, the Americans suggested scouting the small uninhabited island of Shemya on

the far side of Kiska in the Aleutian chain as another possible base. This would also allow flights

to Kiska from two directions and interrupting enemy lines of communication along the chain. How-

ever, its location was also perilously close to heavily Japanese-garrisoned Attu. Reconnaissance

over flights and a visit from S-45, a submarine operated by the Signals Corps for their purposes,

revealed no enemy presence there.47 Securing Shemya was still viewed with apprehension in Ju-

nograd, but also considered good exercise for the Aleutian Task Forces.

Meanwhile the landing craft situation had improved. LCVPs were being built in various Russian

American shipyards, and a first handful of the bigger LCMs had been delivered as patterns. Crews

from the lost destroyer Schastlivy and submarine Skumbrii were recycled to man the new small

craft on the basis that they already had experience in running vessels aground. New, more powerful

davits and derricks were fitted to the ships which would carry them. By June, enough capacity to

land a regimental battlegroup in a single wave was expected to be available. Planners were more

worried about capacity of the transport ships though, due to new equipment introduced. The sealift

squadrons which were once planned to embark a full division each were found to accommodate

only two of the new battlegroups with their various vehicles and support weapons. There was suf-

ficient shipping space to conduct the landing of 1st ATF (G), but without additional Allied support

the reinforcements from 2nd ATF would have to be shuttled in.48

Overall, the Allied logistics network was tightening. In addition to the sea and air links along the

Russian American coast, there were plans for road and rail links to Canada, and ultimately the US.

Despite the challenging terrain that had made such considerations seem economically prohibitive

in peacetime, a road was now being punched from the Canadian side towards Junograd, another

towards Whitehorse, intended to cross into Russian America near Tok, where it would meet with

routes from Stoyanka and Krasivayaberga. In addition, a rail route had been mapped out and par-

tially surveyed heading north from Terrace in British Columbia towards Teslin, Yukon. This would

eventually link to Skaguay on the Russian American side; plans for the farther future were going

on to the Medjreki Railway from the Kenikotski copper mines to the port of Cordova – which had

ceased operations in 1938 after the good ore ran out – and eventually again to Stoyanka.49

Other measures were progressing faster. The initial order of 8,000 Johnson automatic rifles and

400 light machine guns for the Guards, Yeger and Airborne Regiments was nearly completed. The

next batch of 15,000 rifles was destined for the cavalry and marines, who were hoped to be

equipped by early next year; also included were 1,200 MGs which would replace the Lewis Guns

in the Marines. After that, another 17,000 rifles were planned for the infantry regiments in I Corps,

while the RBZ M42 machine gun from domestic production was also being introduced. RBZ was

already working on an automatic rifle design of its own, but MG production was given absolute

priority.50

46 von Sieben, 428. 47 Tanski, p. 22-23. 48 von Sieben, 454. 49 Colins, p. 23. 50 von Sieben, 458-664.

Part III: 1943

28

The new airborne regiment was scheduled to be combat ready at the end of the year, though its

exact organisation was still under debate. Since the Russian American industry was gaining expe-

rience with building wooden airplanes, there were suggestions to look at the British Horsa glider.