The Application of the Risdon Approach for Mandibular Condyle Fracture

Anterior Dislocation of the Intact Mandibular Condyle Caused by Fracture of the Articular Eminence:...

-

Upload

tomoaki-imai -

Category

Documents

-

view

212 -

download

0

Transcript of Anterior Dislocation of the Intact Mandibular Condyle Caused by Fracture of the Articular Eminence:...

b

ob

0

d

J Oral Maxillofac Surg69:1046-1051, 2011

Anterior Dislocation of theIntact Mandibular Condyle Caused

by Fracture of the Articular Eminence:An Unusual Fracture of the

Temporomandibular Joint ApparatusTomoaki Imai, DDS, PhD,* Masahiro Michizawa, DDS, PhD,†

and Makoto Kobayashi, MD, PhD‡

itdt

Maxillofacial injuries often involve fractures of thetemporomandibular joint (TMJ) apparatus, which oc-cur predominantly in the condylar process of themandible.1,2 Fractures of the temporal bone portionof the TMJ, such as the glenoid fossa or articulareminence, are another important group of injuriesdealt with by maxillofacial specialists.3 Fractures ofthe glenoid fossa are occasionally revealed by imagingfor serious head injuries or mandibular trauma.3,4 Anotable manifestation of glenoid fossa fractures isdislocation of the mandibular condyle into the middlecranial fossa,5-7 of which approximately 50 cases have

een reported.8,9

Reports on articular eminence fractures are scarce,10-13

however, possibly because of their rare occurrence oroften-obscured presentation in the presence of othermore serious injuries. Reported cases have beentreated conservatively12,13 or by surgical interventiononly after an incidental finding during operativewound repair.10 This report presents an unusual type

f articular eminence fracture exhibiting a distur-ance of mouth closing and anterior dislocation of the

*Clinical Fellow, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery,

Saiseikai Senri Hospital, Suita, Osaka, and the Department of Oral

and Maxillofacial Surgery II, Osaka University Graduate School of

Dentistry, Suita, Osaka, Japan.

†Head, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Saiseikai

Senri Hospital, Suita, Osaka, Japan.

‡Head, Intensive Care Unit, Senri Critical Care Medical Center,

Saiseikai Senri Hospital, Suita, Osaka, and Director, Tajima Emer-

gency and Critical Care Medical Center, Toyooka Hospital,

Toyooka, Hyogo, Japan.

Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr Imai: De-

partment of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery II, Osaka University

Graduate School of Dentistry, 1-8 Yamadaoka, Suita, Osaka 565–

0871, Japan; e-mail: [email protected]

© 2011 American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons

278-2391/11/6904-0022$36.00/0

oi:10.1016/j.joms.2010.02.051

1046

ntact mandibular condyle caused by a fragment ofhe eminence lodged in the glenoid fossa. We alsoiscuss the causative mechanisms of this fracture pat-ern and its management.

Report of a Case

A 23-year-old man was transferred under paramedic careto the emergency department at our institution after suffer-ing a significant laceration to the right preauricular region ina motorbike accident. On primary survey, his airway waspatent, but he exhibited weak thoracic motion and reducedlung sounds. He had a reduced level of consciousness witha Glasgow Coma Scale score of 8 (E2V1M5). He was subse-quently orally intubated, ventilated, and sedated, and amassive fluid infusion was commenced. A chest radiographshowed right pulmonary contusion. On secondary survey,computed tomography (CT) revealed traumatic subarach-noid hemorrhage and facial bone fractures. Neither cere-brospinal fluid otorrhea nor rhinorrhea was evident. Cranialnerves could not be assessed because of the severe headinjuries. On the right side of the patient’s face, there was apreauricular contused-lacerated wound approximately 7 cmin length that extended horizontally to the zygoma acrossthe zygomatic arch. The wound communicated with theexternal auditory meatus but not the oral cavity. Bleedingfrom small vessels was halted and the wound irrigated withnormal saline solution before the laceration was sutured.The patient received a blood transfusion and was thentransferred while intubated to the intensive care unit.

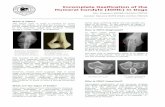

The following day, a subsequent head CT showed nosigns of deterioration in the intracranial hemorrhage, andthe patient was referred to the Department of Oral andMaxillofacial Surgery for consultation. Facial CT showed aslightly laterally rotated fracture of the zygomaticomaxillarycomplex and comminuted fractures of the zygomatic archand articular eminence (Fig 1). The orbital floor, the man-dibular bone including the condylar process, and the pe-trous part of the temporal bone were all intact. A fragmentof the articular eminence was impacted posteriorly into theglenoid fossa, resulting in persistent anterior dislocation ofthe mandibular condyle. Although malocclusion was antic-ipated, occlusal examination was impossible because of oralintubation. On the fourth day, a chest radiograph showedclear lung fields, and the patient was extubated and subse-

quently maintained a stable respiratory status. We were

ilrwioptsctmt

uoftrgnoalslfommatwtt

bdadoatdmotTfo

IMAI ET AL 1047

then able to observe that the midline of the mandible wasdeviated to the left, and there was severe restriction ofmandibular opening and closing (Fig 2). By day 9, a gradualmprovement in the patient’s level of consciousness al-owed us to apply maxillomandibular fixation (MMF) toeposition the condyle into the glenoid fossa; however, thisas ineffective because of the eminence fragment interfer-

ng with the condyle in the fossa. Ophthalmologic andtorhinolaryngologic examinations detected no visual com-lications, taste disturbances, or hearing deficits. The pa-ient’s face was symmetrical at rest with a nonflattenedhape to the malar eminence. The eyes were able to closeompletely, there was no eyelid droop, and the angles ofhe mouth moved symmetrically; however, there was nootor function in the right forehead. There was no pares-

FIGURE 1. Computed tomography images showing fractures ofthe articular eminence, zygomatic arch, and zygomaticomaxillarycomplex: the superficial free fragment derived from the articulareminence including the tubercle (star) and the deeper fragment(arrow) derived from the other part of the eminence, which was themain contributor to obstructing condylar movement. A, Axial imageshowing 2 fragments of the articular eminence dislocated posteri-orly with external rotation. The zygomatic body is also fracturedwith slight external rotation. B, Three-dimensional computed tomog-raphy image showing the articular eminence fragment lodged inthe glenoid fossa and anterior dislocation of the intact mandibularcondyle.

Imai et al. Unusual Fracture of the Articular Eminence. J OralMaxillofac Surg 2010.

hesia of the infraorbital area.

Consequently, on day 11, we performed open surgerynder general anesthesia with nasal intubation. After re-pening the sutured wound, we first found an isolated boneragment of the articular eminence including the articularubercle, situated superficial to the TMJ. On deeper explo-ation, we subsequently identified another fragment in thelenoid fossa, along with obliteration of the articular emi-ence (Fig 3). The TMJ capsule was ruptured with exposuref the upper joint space. The former fragment was notttached to the periosteum and was therefore removed. Theatter fragment was reduced from the fossa without exces-ive bleeding or intracranial perforation. The anteriorly dis-ocated condyle could therefore be repositioned into theossa with manipulation of the mandible, and the normalcclusal position was eventually restored. The deeper frag-ent of the articular eminence and the comminuted frag-ents of the zygomatic arch were fixated with a miniplate

nd stabilized with absorbable sutures. The likely transectedemporal branch of the facial nerve could not be identifiedith a nerve stimulator among the contused subcutaneous

issues. The ruptured articular ligament was sutured, andhe wound was subsequently closed.

Postoperatively, the mandibular deviation relapsed slightlyecause of swelling of the TMJ, but additional maxilloman-ibular fixation was not necessary because the patient wasble to induce his mandible to the occlusal position. Near-aily jaw exercises commenced, and the degree of mouthpening gradually increased to 45 mm with maintenance ofstable occlusal position (Fig 4). Postoperative complica-

ions of taste disturbance or hearing deficit were not evi-ent. Six months later, the patient achieved sufficient jawotion without pain around the TMJ, showed no evidence

f additional complications, and was not concerned abouthe right forehead paralysis. Follow-up lateral panoramicMJ projections revealed normal condylar position in the

ossa on jaw closing and sufficient condylar movement onpening (Fig 5).

Discussion

To our knowledge, only a few reports in Englishhave described fractures of the temporal bone artic-

FIGURE 2. Preoperative malocclusion. The mandible was devi-ated to the left because of anterior dislocation of the right condyle,with disturbance of mouth opening and closing.

Imai et al. Unusual Fracture of the Articular Eminence. J Oral

Maxillofac Surg 2010.

oit

act

IM

1048 UNUSUAL FRACTURE OF THE ARTICULAR EMINENCE

ular eminence (Table 1). The case described here isunique among these in that the mandibular condylewas anteriorly dislocated and unable to restitute intothe glenoid fossa because of obstruction by a frag-ment of the fractured articular eminence. Four of the5 reported cases, including the present case, wereaccompanied by a large ipsilateral preauricular lacer-ation, indicating that this type of fracture may mostoften be caused by a direct lateral force impacting onor near the articular eminence, which is more protu-berant than the glenoid fossa and mandibular con-dyle. This contrasts with condylar fractures, whichexemplify fractures incurred by an indirect force.

Fractures of the TMJ apparatus can vary in patternand severity according to the condylar position and

FIGURE 3. Intraoperative view of preauricular laceration andfractured articular eminence. A, View of the opened wound show-ing anteriorly dislocated condyle with ruptured articular capsule(white arrow). The superficial fragment (star) was subsequentlyremoved and the deeper fragment (black arrowhead) was re-duced. B, View of relocated condyle in the fossa showing exposureof the upper joint cavity with no apparent injury to the articular disk(white arrowhead).

Imai et al. Unusual Fracture of the Articular Eminence. J Oral

Maxillofac Surg 2010.individual morphostructural variations of the TMJ, aswell as the size and direction of the external force.For example, there is a predisposition in childhood tointracranial dislocation of the intact condyle becauseof a relatively smaller and more rounded condylarhead and thinner roof of the glenoid fossa.6,14 More-

ver, a wide mouth opening at the instant of impacts thought to increase the risk of intracranial disloca-ion of the intact condyle7 or condylar fracture,15

whereas fractures incurred while the mouth is closedshow a predilection for the subcondylar region.15 Inddition, mouth opening on impact seemed to be aontributing factor in superolateral condylar disloca-ion into the temporal fossa.16

When fracture fragments of the articular eminenceare displaced, they may normally move inferiorly oranteriorly because there are bony structures posteri-orly and superiorly—namely, the mandibular condyleand the zygomatic process of the temporal bone,respectively. In the present case, however, there wasan anterior-posterior positional interchange betweenthe eminence fragments and condyle. Because thispattern was unlikely to occur as long as the condyleremained in the glenoid fossa, we believe that themost likely causative mechanism of this injury is asfollows: at the moment of impact of the face with theroad surface, the patient opened his mouth widely interror, moving the condyle anteriorly out of the fossa.The direct anterolateral force tore the preauricularsoft tissue, comminuted the zygomatic arch, and frac-tured and slightly laterally rotated the zygomatico-maxillary complex. Concomitantly, the articular emi-nence was also fractured into 2 fragments, and one ofthem slid backward into the vacant fossa, impedingthe restitution of the condyle. Allowing for the ex-

FIGURE 4. Postoperative re-established occlusion.

mai et al. Unusual Fracture of the Articular Eminence. J Oralaxillofac Surg 2010.

traordinary sequence of events required for such an

ct

axillo

IMAI ET AL 1049

outcome, we emphasize its dependence on the man-dibular position at the time of impact.

Management of articular eminence fractures de-pends primarily on the patient’s overall medical statusand more specifically on the degree and pattern ofeminence fracture. Because of the high-energy natureof the causative force, major displacement of theeminence fragment may occur concomitant to life-threatening injuries, such as serious temporal bonefractures or intracranial complications, in which casemaxillofacial specialists commonly have no choiceother than conservative management.3 Here, our pa-tient, who initially had an impaired level of conscious-ness, underwent surgical reduction of the articulareminence fragment that was mechanically impedingcondylar movement. Although rare but generallyknown, there are instances in which open reduction

FIGURE 5. Six-month postoperative panoramic temporomandibcontralateral (C and D) sides. A and C, On jaw closing, condylarcondylar movement on the ipsilateral side (B) is sufficient with slighindicate the titanium plate.

Imai et al. Unusual Fracture of the Articular Eminence. J Oral M

of a condylar fracture is indicated when fragments w

from any fracture obstruct movement at the TMJ.1 Toour knowledge, however, this is the first case reportdescribing the surgical treatment of an articular emi-nence fracture based on the preoperative assessmentof a displaced fragment in the glenoid fossa.

Keith et al10 described surrounding soft tissue inju-ries that may be concomitant with articular eminencefractures, including damage of the TMJ capsule result-ing in condylar dysmobility secondary to scarring,chorda tympani injury leading to loss of taste, andstretch injury of the anterior malleolar ligament lead-ing to tearing of the tympanic membrane and conse-quent hearing impairment. Fortunately, neither the 3previously reported cases with established out-comes10,12,13 nor the present case had any of theseomplications. Further, this case illustrates some ofhe issues regarding management of facial lacerations

nt projections for lateral views of the ipsilateral (A and B) andns in the fossa are normal bilaterally. B and D, On jaw opening,inferior movement because of flattening of the eminence. Arrows

fac Surg 2010.

ular joipositiotly less

ith restricted medical resources, particularly those

twatfbartbb

able

1.REP

ORTE

DCA

SES

OF

ARTI

CU

LAR

EMIN

ENCE

FRA

CTU

RE

Rep

ort

Pat

ien

tA

ge(y

rs)

and

Gen

der

Tra

um

atic

Even

tP

reau

ricu

lar

Lace

rati

on

(Len

gth

)D

efin

itiv

eIm

agin

gfo

rD

iagn

osi

sD

islo

cati

on

of

Co

nd

yle

Po

siti

on

of

Frag

men

tO

ther

Cra

nio

faci

alFr

actu

res

Tre

atm

ent

thet

al1

0(1

990)

19,m

ale

Rea

r-se

atp

asse

nge

rin

car

acci

den

tV

erti

cal

(7cm

)N

on

e(i

ntr

aop

erat

ivel

yd

iagn

ose

d)

No

ne

An

teri

or

toco

nd

yle*

Man

dib

le(c

on

tral

ater

alp

aras

ymp

hys

ial

regi

on

and

ipsi

late

ral

ram

us)

Stab

iliza

tio

no

fth

efr

actu

red

emin

ence

frag

men

tw

ith

sutu

res,

follo

wed

by

MM

Ffo

r5

wee

ksec

kian

dW

olf

11

1990

)32

,mal

eA

ssau

ltw

ith

ah

atch

etH

ori

zon

tal

(10

cm)

Pan

ora

mic

x-r

ayN

on

eIn

feri

or

dis

pla

cem

ent

No

ne

No

td

escr

ibed

and

Pec

k12

2001

)31

,mal

eFa

llfr

om

3rd

flo

or

Ver

tica

l(8

cm)

Pan

ora

mic

x-r

ayN

on

eN

od

isp

lace

men

tN

on

eC

on

serv

ativ

etr

eatm

ent

on

lyw

ith

ou

tM

MF

auch

iet

al1

3

2006

)24

,mal

eSt

ruck

on

chin

by

stee

rin

gw

hee

lin

aca

rac

cid

ent

No

ne

MR

Ian

dax

ial

CT

No

ne

No

dis

pla

cem

ent

Gle

no

idfo

ssa

Co

nse

rvat

ive

trea

tmen

to

nly

wit

ho

ut

MM

F

sen

tca

se23

,mal

eM

oto

rbik

eac

cid

ent

Ho

rizo

nta

l(7

cm)

CT

An

teri

or

Gle

no

idfo

ssa

Zyg

om

atic

om

axill

ary

com

ple

xan

dzy

gom

atic

arch

Rem

ova

lo

fin

terf

erin

gfr

agm

ent

tore

po

siti

on

con

dyl

ein

tofo

ssa

bre

viat

ion

s:C

T,

com

pu

ted

tom

ogr

aph

y;M

MF,

max

illo

man

dib

ula

rfi

xat

ion

;M

RI,

mag

net

icre

son

ance

imag

ing.

Deg

ree

of

dis

pla

cem

ent

un

clea

r.

ai

eta

l.U

nu

sua

lFr

act

ure

of

the

Art

icu

lar

Em

inen

ce.J

Ora

lM

axi

llofa

cSu

rg2

01

0.

1050 UNUSUAL FRACTURE OF THE ARTICULAR EMINENCE

related to a traumatic swollen face in a patient ob-tunded because of severe head injuries. Emergencyphysicians rightly prioritize lifesaving treatment dur-ing primary care, which may, however, hamper eval-uation of facial nerve injury, identification of the tran-sected branches, and neurorrhaphy.

Temporal bone fractures are traditionally classifiedinto 2 prominent patterns, longitudinal and transversetypes.3,17 The former typically results from a directlateral blow to the skull, and the fracture line runsthrough the external auditory canal, parallel to thepetrous ridge and to the foramen ovale, whereas thelatter is commonly caused by an anteroposterior blowto the skull resulting in a fracture line perpendicularto the petrous ridge and is accompanied by a poorerprognosis. Ort et al18 reported that both types ofemporal bone fractures can occur in conjunctionith fractures of the TMJ portion in childhood, and

lthough the portion of the TMJ apparatus involved inhese fractures was not classified, they likely involvedracture of the articular eminence, glenoid fossa, oroth. Articulator eminence fractures may be associ-ted with longitudinal fractures because both canesult from a lateral blow, whereas glenoid fossa frac-ures may be associated with either type of temporalone fracture because either a lateral or occipitallow can be transmitted throughout the skull base,3

which includes the glenoid fossa.In conclusion, management of atypical fractures

involving the TMJ are a challenging responsibilityoften falling to maxillofacial specialists, who musttake account of potential concomitant temporal bonefractures and intracranial complications in coopera-tion with emergency physicians, otorhinolaryngolo-gists, and neuro specialists. In any fracture of the TMJapparatus, surgical intervention followed by postop-erative exercises should be carefully considered, par-ticularly when fracture fragments impede condylarmovement.

References1. Chacon GE, Larsen PE: Principles of management of mandibu-

lar fractures, in Miloro M, Ghali GE, Larsen PE, et al (eds):Peterson’s Principals of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Hamil-ton, Canada, BC Decker, 2004, pp 401-433

2. Zachariades N, Mezitis M, Mourouzis C, et al: Fractures of themandibular condyle: A review of 466 cases. Literature review,reflections on treatment and proposals. J Craniomaxillofac Surg34:421, 2006

3. Gladwell M, Viozzi C: Temporal bone fractures: A review forthe oral and maxillofacial surgeon. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 66:513, 2008

4. Iannetti G, Martucci E: Fracture of glenoid fossa followingmandibular trauma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 49:405,1980

5. Barron RP, Kainulainen VT, Gusenbauer AW, et al: Fracture ofglenoid fossa and traumatic dislocation of mandibular condyleinto middle cranial fossa. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral

Radiol Endod 93:640, 2002T

Kei

Rad

(T

ay(

Miy (

Pre Ab *

Im

IMAI ET AL 1051

6. Cillo JE, Sinn DP, Ellis E 3rd: Traumatic dislocation of themandibular condyle into the middle cranial fossa treated withimmediate reconstruction: A case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg63:859, 2005

7. Musgrove BT: Dislocation of the mandibular condyle into themiddle cranial fossa. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 24:22, 1986

8. Barron RP, Kainulainen VT, Gusenbauer AW, et al: Manage-ment of traumatic dislocation of the mandibular condyle intothe middle cranial fossa. J Can Dent Assoc 68:676, 2002

9. Ohura N, Ichioka S, Sudo T, et al: Dislocation of the bilateralmandibular condyle into the middle cranial fossa: Review ofthe literature and clinical experience. J Oral Maxillofac Surg64:1165, 2006

10. Keith O, Jones GM, Shepherd JP: Fracture of the articulareminence. Report of a case. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 19:79,1990

11. Radecki CA, Wolf SM: Solitary fracture of the articular emi-nence. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 69:768, 1990

12. Tay AB, Peck RH: Solitary fracture of the articular eminence: Acase report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 59:808, 2001

13. Miyauchi K, Sano K, Nagai M, et al: Occult fractures of articulareminence and glenoid fossa presenting as temporomandibulardisorder: A case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol OralRadiol Endod 101:e101, 2006

14. da Fonseca GD: Experimental study on fractures of the man-dibular condylar process (mandibular condylar process frac-tures). Int J Oral Surg 3:89, 1974

15. Petzel JR, Bulles G: Experimental studies of the fracture behav-iour of the mandibular condylar process. J Maxillofac Surg9:211, 1981

16. Bu SS, Jin SL, Yin L: Superolateral dislocation of the intactmandibular condyle into the temporal fossa: Review of theliterature and report of a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral PatholOral Radiol Endod 103:185, 2007

17. Johnson F, Semaan MT, Megerian CA: Temporal bone fracture:Evaluation and management in the modern era. OtolaryngolClin North Am 41:597, 2008

18. Ort S, Beus K, Isaacson J: Pediatric temporal bone fractures

in a rural population. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 131:433,2004