Anemia, Diaetes and Chronic Kidney Disease

Transcript of Anemia, Diaetes and Chronic Kidney Disease

-

7/25/2019 Anemia, Diaetes and Chronic Kidney Disease

1/7

Anemia, Diabetes, and Chronic KidneyDiseaseUZMAMEHDI, MDROBERTD. TOTO, MD

Diabetes is the leading cause ofchronic kidney disease (CKD) andis associated with excessive cardio-

vascular morbidity and mortality (1,2).Anemia is common among those with di-abetes andCKD andgreatly contributes topatient outcomes (3,4). Observationalstudies indicate that low Hb levels in suchpatients may increase risk for progressionof kidney disease and cardiovascular mor-bidity and mortality (5). Controlled clin-ical trials of anemia treatment witherythropoietin stimulating agents (ESAs)demonstrated improved quality of life(QOL) but have not demonstrated im-proved outcomes (6 10). In some trials,ESA treatment for high Hb levels is asso-ciated with worse outcomes such asincreased thrombosis risk (6,11). Con-sequently, the U.S. Food and Drug Ad-ministration (FDA) and the NationalKidney Foundation (NKF) have modifiedtheir recommendations regarding anemiatreatment for CKD patients (12). The ob-

jectives of this review are to1) update cli-

nicians on the prevalence, causes, andclinical consequences of anemia; 2) dis-cuss the benefits and risks of treatment;and 3) provide insight into anemia man-agement based on clinical trial evidence inpatients with diabetes and kidney diseasewho are not on dialysis.

DEFINITION AND

PREVALENCE OF ANEMIA

IN CKD The NKF defines anemia inCKD as an Hb level 13.5 g/dl in menand 12.0 g/dl in women (13). This defini-tion is based on the fact that these levelsare outside the 95% CIs of the mean fornormal men and women. Anemia is com-mon in diabetic patients with CKD (5). Itis estimated that one in five patients withdiabetes and stage 3 CKD have anemia,and its severity worsens with more ad-

vanced stages of CKD and in those withproteinuria (7,14,15) For example, in a5-year prospective observational studyconducted in a diabetes clinic in Austra-lia, anemia was found in early kidney dis-ease, and declining Hb levels were morecommon among those with higher levelsof albuminuria (16) The distribution ofHb in patients with diabetes and CKD issimilar to that in those without diabetes,but on average, Hb levels are lower. Forthese reasons, it is recommended that cli-nicians measure serum creatinine andurine albumin and creatinine to estimateglomerular filtration rate (GFR) and iden-tify and quantitate albumin excretion ratein patients with diabetes and anemiapatients.

CAUSES OF ANEMIA A n e m i ain diabetic patients with CKD may resultfrom one or more mechanisms. Vitamindeficiencies such as folate and B12 are rel-atively uncommon, and clinical practiceguidelines do not recommend routine

measurement of these serum levels. (Seebelow.) The major causes of anemia inCKD patients are iron and erythropoietindeficiencies and hyporesponsiveness tothe actions of erythropoietin.

Iron deficiencyIron deficiency in the general populationis a common cause of anemia and is prev-alent in patients with diabetes and CKD.In these same patients, dietary deficiency,low intestinal absorption, and gastroin-testinal bleeding may result in absoluteiron-deficiency anemia. Recent analysesof the National Health and Nutrition Ex-amination Survey IV suggest that up to50%of patients with CKD stages 25haveabsolute or relative (functional) iron defi-ciency (17). In CKD, both absolute andrelative iron deficiency are common. Ab-

solute iron deficiency is defined as a de-pletion of tissue iron stores evidenced by a

serum ferritin level 100 ng/ml or atransferrin saturation of 20%. Func-tional iron deficiency anemia is adequatetissue iron defined as a serum ferritin level100 ng/ml and a reduction in iron sat-uration. The latter is more common and isstrongly associated with upregulation ofinflammatory cytokines and impaired tis-sue responsiveness to erythropoietin,which can inhibit iron transport from tis-sue stores to erythroblasts (18). Increasedlevels of inflammatory cytokines such asinterleukin-6 enhance production and se-cretion of hepcidin, a hepatic protein that

inhibits intestinal iron absorption and im-pairs iron transport from the reticuloen-dothelial system to bone marrow. Inaddition, erythropoietin, which normallyenhances iron transport from macro-phages to the blood stream, is impaired,thereby exacerbating relative iron defi-ciency (19).

Erythropoietin deficiency andhyporesponsivenessBoth deficiency and hyporesponsivenessto erythropoietin contribute to anemia in

diabetic patients with CKD (15,20). Thecause of erythropoietin deficiency inthese patients is thought to be reducedrenal mass with consequent depletion ofthe hormone. Hyporesponsivness is de-fined clinically as a requirement for highdoses of erythropoietin in order to raiseblood Hb level in the absence of iron de-ficiency. It is believed to represent impairedantiapoptotic action of erythropoietin onproerythroblasts. Possible causes of thiserythropoietin hyporesponsiveness includesystemic inflammation and microvasculardamage in the bone marrow (15,20). How-ever, some studies suggest that other factors(i.e., autonomic failure) may play a role inimpaired erythropoietin production or se-cretion by failing kidneys (21).

Nephrotic syndromeNephrotic syndrome characterized byedema, hypoalbuminemia, dyslipidemia,and urine protein-to-creatinine ratio 3is not uncommon in patients with dia-betic nephropathy and can occur even inearly stages of CKD (e.g., stages 12)(21,22). The mechanism of anemia in ne-

From the Department of Nephrology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas.Corresponding author: Robert D. Toto, [email protected] 23 April 2008 and accepted 14 April 2009.DOI: 10.2337/dc08-0779 2009 by the American Diabetes Association. Readers may use this article as long as the work is properly

cited, the use is educational and not for profit, and the work is not altered. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ for details.

R e v i e w s / C o m m e n t a r i e s / A D A S t a t e m e n t s

R E V I E W

1320 DIABETESCARE, VOLUME32, NUMBER7, JULY2009

-

7/25/2019 Anemia, Diaetes and Chronic Kidney Disease

2/7

phrotic syndrome is complex and in-volves both inflammatory-mediatedmechanisms as discussed above as well asabsolute iron deficiency. Iron excretionincreases in early stages of kidney diseasein patients with diabetes and albuminuriaand is exacerbated by development of ne-phrotic-range proteinuria. In nephrotic

syndrome, many nonalbumin proteinsare excreted in the urine, including trans-ferrin and erythropoietin. Significantlosses of transferrin and erythropoietincan occur in nephrotic syndrome, leadingt o bot h iron- a nd e ryt hropoie t in-deficiencycaused anemia in patientswith diabetes (23). Evidence for in-creased transferrin catabolism in ne-phrotic syndrome may contribute toiron deficiencycaused anemia (24).Decreased erythropoietin production,secretion, and hyporesponsiveness can

contribute to anemia in nephrotic pa-tients. (See above.)

ACE inhibitors and angiotensinreceptor antagonistsBoth of these drug classes may cause areversible decrease in Hb concentrationin patients with diabetes and CKD (25).The mechanisms by which ACE inhibi-tors and angiotensin receptor blockerslower Hb include a direct blockade of theproerythropoietic effects of angiotensin IIon red cell precursors, degradation ofphysiological inhibitors of hematopoiesis,

and suppression of IGF-I. Long-term ad-ministration of losartan in 50- to 100-mgdoses once daily in patients with diabetesand albuminuria is expected to lower Hbby 1 g/dl. Importantly, this effect doesnot diminish the renoprotective effect oflosartan. It should be recognized thatthese classes of agents may induce orworsen symptomatic anemia in nephrop-athy patients (26).

CONSEQUENCES OF

ANEMIA

Quality of lifeAnemia is an important cause of physicaland mental impairments in diabetic CKDpatients including malaise, fatigue, weak-ness, dyspnea, impaired cognition, andother symptoms. Clinical trials indicatethat improving anemia improves cogni-tive function, sexual function, generalwell-being, and exercise capacity and re-duces the need for blood transfusions(6,8 10,27) There is renewed evidenceof anemia in diabetes contributing toretinopathy, neuropathy, diabetic foot ul-

cer, hypertension, progression of kidneydisease, and cardiovascular events (15).

Progression of kidney diseaseIn general, kidney disease in diabetes isprogressive, and it has been hypothesizedthat anemia may contribute to progres-sion of kidney disease (7,16,28,29). Pos-

sible mechanisms include renal ischemiacaused by reduced oxygen delivery due tolow Hb and underlying heart failure. Forexample, anemia may worsen renal med-ullary hypoxia, leading to renal interstitialinjury and fibrosis (30,31). Whole animaland in vitro studies indicate that renalhypoxia upregulates hypoxia-induciblefactor-1, a transcriptional regulator ofthe erythropoietin gene as well as hemeoxygenase, nitric oxide synthases, extra-cellular matrix, and apoptosis genes. It isupregulated by renal hypoxia and induces

collagen gene expression in renal fibro-blasts, thereby increasing interstitial fi-brosis. Anemia may also increase renalsympathetic nerve activity, resulting inincreased glomerular pressure and pro-teinuria (which in turn may accelerateprogression of kidney disease), and con-tribute to worsening kidney function byexacerbating underlying heart failureacommon complication in patients withdiabetes and kidney disease, (29).

Early animal model studies in renalablation, hypertension, and diabetesdemonstrated that treatment of anemia

worsened systemic and glomerular hy-pertension and renal structural and func-tional damage, suggesting that anemiamay actually be renoprotective (32,33).Recently, Nakamura et al. (34) demon-strated that administration of an erythro-poietin-stimulating agent to patients withanemia and CKD decreased urine fattyacidbinding proteina molecule knownto be associated with increased risk forkidney disease progressionsuggestingthat ESA may have a renoprotective effectindependent of Hb level. However, in

clinical trials, erythropoietin has not yetbeen proven to slow kidney disease pro-gression in patients with diabetes and ne-phropathy. (See below.)

Cardiovascular diseaseObservational studies indicate that deathis five times more likely than progressionto end-stage kidney disease in patientswith CKD (35). Moreover, cardiovasculardisease is the most common cause ofdeath in patients with diabetes and CKD;and anemia appears to be a risk multiplierfor all-cause mortality among those same

patients. Anemia prevalence is up to 10-fold higher among diabetic patients withCKD and heart failure and is a modifiablerisk factor among diabetic patients (36,37). Low Hb concentration is an indepen-dent risk factor for left-ventricular hyper-trophy, heart failure, and cardiovascularmortality (3744). Heart failure is com-

mon in diabetic patients with nephropa-thy and may result in reduced renal bloodflow, thereby contributing to further re-duction in GFR and erythropoietin pro-duction. Also, anemia may aggravatetissue hypoxia, and subsequently heartfailure, resulting in further renal sodiumretention, volume expansion, increasedvenous return, and increased venomotor.For these reasons, treatment of anemia inpatients with diabetes and CKD is a pro-posed strategy to reduce excessive cardio-vascular morbidity and mortality. (See

below.)

CLINICAL TRIALS OF

ERYTHROPOIETIN-

STIMULATING AGENTS I t i simportant to note that none of the pub-lished trials examining the safety and ef-ficacy of ESA for anemia treatmentincluded a placebo control group. Withone exception (45), all study subjects(with varying Hb levels) were treated withan ESA.

RENAL OUTCOMES Several small

trials in patients with CKD, includingthose with diabetes, demonstrated a ben-eficial effect on kidney disease progres-sion. Kuriyama et al. (45) studied 106patients with stage 34 CKD with orwithout anemia. Those with anemia wererandomized to ESA treatment or no treat-ment. The time to a doubling of serumcreatinine from baseline was the studysprimary end point. They found that timeto doubling of serum creatinine was sig-nificantly longer in the treated group thanin the nontreated group and similar to

that in the nonanemic control subjects(45). Gouva et al. (46) randomized 88anemic stage 35 CKD patients to earlyversus late treatment with erythropoie-tin- to test the hypothesis that thisintervention would slow the rate of pro-gression to end-stage renal disease(ESRD). They found that early correctionof anemia was associated with improvedrenal and patient survival compared withdelayed treatment of anemia. Rossert et al.performed a randomized controlled trialinvolving 390 patients with stage 34CKD and anemia to test the hypothesis

Mehdi and Toto

DIABETESCARE, VOLUME 32, NUMBER7, JULY2009 1321

-

7/25/2019 Anemia, Diaetes and Chronic Kidney Disease

3/7

that treatment of anemia with an ESA toreach a higher Hb level would slow de-cline in kidney function. Subjects weretargeted to one of two Hb levels (1315 or1112 g/dl) and followed for 12 months.

Although the decline in GFR was numer-ically less in the high-Hb group, this dif-ference was not statistically significant.

Still, those randomized to the high groupshowed improvement in QOL and vitality(47). However, the two largest trials todate to examine the effect of ESA on pro-gression of kidney disease (as a secondaryoutcome) did not show any renal benefitof raising Hb to a higher level. (Seebelow.)

CARDIOVASCULAR

OUTCOMES Roger et al. (9) con-ducted a prospective, randomized, open-label trial in 155 anemic CKD patients

(stage 34), testing the hypothesis thatESA treatment could prevent develop-ment or progression of left-ventricularhypertrophy. Study subjects were ran-domized to receive subcutaneous dosingwith erythropoietin- to achieve andmaintain Hb in the range of 910 or1113 g/dl and followed for 2 years withrepeated measures of left-ventricularstructure and function. They found nodifference in the primary outcome of left-ventricular wall thickness; however,those assigned to the higher Hb arm of thestudy experienced improvement in QOL.

Levin et al. (8) conducted a randomizedclinical trial to test the hypothesis thatprevention or correction of anemia, byimmediate versus delayed treatment witherythropoietin- in patients with CKD,would delay or prevent left-ventricularhypertrophy. The primary outcome wasthe change in left-ventricular mass index.They randomized 176 CKD patients whohad experienced a decrease of 1 g/dl Hb inthe prior year and a baseline Hb level of1113.5 g/dl to treatment with epoetin-to maintain Hb in the range of 1214 g/dl

or to maintain a target Hb range of 910.5g/dl; the subjects were followed for 24months with repeated measures of left-ventricular structure and function. De-spite significant difference in Hb levelbetween groups, they found no significantdifference in left-ventricular mass index.Those assigned to higher Hb experiencedimprovement in QOL (Table 1).

Ritz et al. randomized 172anemic pa-tients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes andstage 13 CKD to treatment with epo-etin- and a target Hb level of either1315 or 10.511.5 g/dl and followed

them for 19 months. The primary out-come was the change in left-ventricularmass index, and secondary outcomes in-cluded kidney function and QOL. Therewere no significant differences in left-ventricular mass index in those random-ized to the higher target; however, QOLmeasures were significantly better in the

higher Hb arm. There were no differencesin kidney function decline and no signif-icant differences in adverse events (48).

CARDIOVASCULAR

EVENTS Singh et al. (11) tested thehypothesis that a higher Hb level wouldreduce risk for the composite cardiovas-cular outcome of stroke, myocardial in-farction, heart failure, and all-causecardiovascular mortality among patientswith various causes of CKD including di-abetes (46%). In this trial, the Correc-

tion of Hb and Outcomes in RenalInsufficiency (CHOIR) trial, 1,432 pa-tients with anemia and stage 34 CKDwere randomized to an Hb target of 11.5or 1313.5 g/dl and followed for an aver-age of 16 months (11). During the trial,Hb levels were significantly higher inthose randomized to the higher Hb arm.The composite event rate was higher inthose assigned to the higher Hb arm;however, there was no difference in therate of development of ESRD. Also, incontrast to the results of other studies,there was no improvement in QOL in

those randomized to the higher target.The authors concluded that use of a targetHb level of 13.5 g/dl (compared with 11.3g/dl) was associated with increased riskand no incremental improvement inQOL. Post hoc analysis demonstratedthata higher fraction of patients in the higherHb arm had prior coronary events, hyper-tension, and dropout prior to an event orcompletion of the study. In the Cardio-vascular risk Reduction by Early AnemiaTreatment with Epoetin beta (CREATE),Drueke et al. (6) randomized 603 patients

with stage 34 CKD, from various causesincluding diabetes (25%), to early ver-sus late treatment with epoetin- to testthe hypothesis that a higher Hb levelwould reduce risk for cardiovascularmorbidity and mortality. Subjects wererandomized to an Hb target range of 1111.5 or 1315 g/dl and followed for anaverage of 36 months. They found no sig-nificant differences in the primary com-posite outcome, but there was a trendtoward a higher event rate in the higherHb arm. In addition, multiple QOL mea-sureswere significantly improved in those T

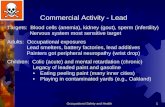

able1Randomizedcontrolledcardiovascularoutcometrialsofanemiatreatmentwitherythropoietin-stimulatingagentsinpatientswithchronickidneydisease

N

Diabetes

(%)

Studydesign

Stageofstudy

popu

lation

HCT/Hbtarget

Follow-up

(months)

Primaryoutcome

Results

QOL

Rogeretal.

155

2433

Openlabel

3

5

910/1213

24

LVMI

Nobe

nefit

Improved

Levinetal.

172

3541

Openlabel

2

5

910.5

/1214

22.6

LVMI

Nobe

nefit

Improved

Singhetal.

1,4

32

48

Openlabel

4

5

1111.5

/1313.5

16

Deathorcardiovascularevent

Worseinhigh

Hb

arm

Nodifference

Drueckeetal.

603

25

Openlabel

4

5

1111.5

/1315

36

Deathorcardiovascularevent

Nobe

nefit

Improved

Ritzetal.

176

100

Openlabel

Stag

e13

1315/10.511.5

18

LVH

Nobe

nefit

Improved

Mixetal.

4,0

00

100

Double-blindandplacebocontrolled

3

4

13.0

/11.0

2448

Deathorcariovascularevents

Trialongoing

Trialongoing

HCT,

hematocrit;HD,

hemodialysis;LVH,le

ftventricularhypertrophy;LVMI,left-ventricu

larmassindex.

Anemia, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease

1322 DIABETESCARE, VOLUME32, NUMBER7, JULY2009

-

7/25/2019 Anemia, Diaetes and Chronic Kidney Disease

4/7

randomized to the higher Hb arm. In con-trast to the CHOIR study, the time toESRD, a secondary outcome, was shorterin the higher Hb arm. Post hoc analysisdemonstrated that the study was under-powered to detect a difference in the pri-mary outcome variable as a result of thelower-than-expected overall event rate in

both arms of the study.The increased risk for adverse out-

comes during ESA treatment of anemiain clinical trials of patients with CKD isnot completely understood. One possi-bility is that higher Hb increases risk forthrombosis. Another possibility is thatthose who experience adverse cardio-vascular events have higher comorbidity,are relatively resistant to erythropoietin,and require higher doses of ESA toachieve higher Hb and that the higherdoses of ESA are vasculotoxic (49). Fur-

ther studies are needed to determinewhether higher doses versus resistance toaction of ESA cause harm in anemic pa-tients with CKD. The Trial of Reductionof End points with Aranesp Therapy(TREAT) is an ongoing large-scale, ran-domized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled study including 4,000 anemicpatients with type 2 diabetes and CKD(50). The primary outcome is a compositeof all-cause mortality and cardiovascularmorbidity. This ongoing trial is unique inmany respects, including the double-blind, placebo-controlled design; the

population of exclusively anemic patientswith type 2 diabetes and CKD; and a largesample size. This study will add impor-tant new information concerning benefitsand risks of ESA treatment of anemia inpatients with diabetes and CKD. Resultsare expected in 2010.

In summary, two clear messagesemerge from the anemia treatment trials.1) Treating patients to achieve a highercompared with a lower Hb target typicallyimproves QOL. 2) Treatment to reach ahigher Hb level does not reduce risk for

cardiovascular events and may causeharm.

CLINICAL PRACTICE

GUIDELINES FOR

EVALUATION OF ANEMIA TheNKF clinical practice guidelines for diag-nosis and management of anemia in pa-tients with CKD recommend a routinehistory and physical examination, a com-plete blood count, a reticulocyte count,evaluation of serum iron and total ironbinding capacity and serum ferritin level,and a fecal test for occult blood for eval-

uation of anemia (13,51). Additional teststo evaluate anemia should be guided bythis initial evaluation (e.g., serum folicacid, vitamin B12 level, Coombs test,etc.). Despite the high prevalence of ane-mia in the CKD population, treatmentwith erythropoietin or iron often is notused in the predialysis period. For exam-

ple, nearly 70% of patients initiated ondialysis are anemic by the NKF definitionbut are not treated with erythropoietin,and 50% of these patients have severeanemia (hematocrit 30%).

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR

TREATMENT OF ANEMIA

NKF clinical practice guidelinesThe NKF currently recommends thatwhen treating anemia in CKD with anESA, the Hb target range should be 1112

g/dl and should not exceed 13 g/dl (51).In addition, the NKF recommends thattreatment should be individualized, tak-ing into account patient characteristics in-c luding sympt oms, Hb le ve l , a ndevaluation for other causes of anemia.(See above.) If the initial evaluation indi-cates absolute iron deficiency as thecause, treatment with supplemental ironand a search for the cause of iron lossshould be undertaken. If absoluteiron de-ficiency is not present and causes otherthan kidney disease are excluded, thentreatment with an ESA should be admin-

istered at a dose sufficient to increase Hbwithin the target range of 1112 g/dl. Im-portantly, ESA-treated patients should, ingeneral, receive iron to ensure that ade-quate stores are available for erythropoi-etic response (51). The NKF notes thatwith few exceptions, anemia treatmenttrials in CKD patients demonstrated thattreatment with an ESA to achieve Hb val-ues in the range of 1113 g/dl is associ-ated with improved QOL.

Food and Drug Administration

In early 2007, the Food and Drug Admin-istration (FDA) promulgated new recom-mendations for use of ESA in patientswith CKD, advising them that ESA canincrease risk for heart attack, stroke,blood clots, heart failure, and death whengiven to maintain higher Hb (52). Drugsaffected by their recommendation in-cluded epoetin- and darbepoetin. TheFDA advised practitioners to use the low-est dose of an ESA needed to avoid bloodtransfusion, targeting blood Hb in therange of 1012 g/dl, and to withhold thedose of ESA when Hb level exceeds 12

g/dl. Manufacturers of ESA accordinglyadded black box warnings noting theserecommendations (53).

In summary, the NKF and FDA rec-ommendations are in conflict. Whereasthere is agreement that ESAs are valuablefor treating anemia, they differ with re-gard to the level of Hb at which to initiate

ESA and the upper limit of the Hb target.The NKF supports the safety of ESA useand recognizes the importance of individ-ualizing anemia treatment. Further stud-ies on the safety of ESA use in the diabetespopulation, as well as efforts to better un-derstand the explanation for the associa-tionof higher Hb with worse cardiovascularoutcomes reported in clinical trials, areneeded.

ANEMIA MANAGEMENT Thefirst step in the management of anemia is

evaluating the underlying cause. (Seeabove on diagnosis and evaluation.) If ab-solute iron deficiency is present, the pa-tient should be put on oral or intravenousiron therapy. Several oral iron prepara-tions are available for treatment includingferrous gluconate, fumarate, and sulfate.Doses of 300325 mg of one of theseagents three times daily can increase theHb level significantly in such patients.Notably, significant gastrointestinal sideeffects may lead to poor adherence andcompliance with oral iron. An alternativeis to administer intravenous iron on a pe-

riodic basis. Several studies indicate thatthese preparations are effective and safe inpredialysis populations (11,54,55). Dah-dah et al. (54) administered intravenousiron dextran to anemic, iron-deficient (se-rum ferritin 100 ng/ml or transferrinsaturation 20%) patients with an esti-mated GFR50 ml/min and not on dial-ysis in doses of either 200 mg/week for 5weeks or 500 mg/week for 2 weeks. Sig-nificant increases in Hb occurred within 2weeks; all patients tolerated infusionswithout serious adverse reactions. Intra-

venous iron preparations including ferricsodium gluconate, iron sucrose, and irondextran are available and can be adminis-tered safely. Among these agents, irondextran has been associated with thehighest incidence of adverse reactions, al-though the incidence of such reactions islow with all three preparations. Althoughsome studies indicate that intravenousiron is in general more efficacious thanoral iron for achieving increases in Hb inpatients with CKD, oral iron is also effec-tive (55). Moreover, no definite advan-tages have been shown with intravenous

Mehdi and Toto

DIABETESCARE, VOLUME 32, NUMBER7, JULY2009 1323

-

7/25/2019 Anemia, Diaetes and Chronic Kidney Disease

5/7

versus oral iron in patients with CKD noton dialysis (56).

An initial dose of 10,000 units epoetin-once weekly or 0.75g/kg darbepoetin-every otherweek subcutaneouslyare effec-tive for increasing Hb concentration by12 g/dl over 48 week periods (27).Darbepoetin can be administered subcu-

taneously every other week at outset andthen administered once monthly to main-tain Hb target. Ling et al. (57) demon-strated efficacy of maintaining Hb in therange of 1012 g/dl (total dose of 88 g)after extending the dosing interval fromevery other week to once every 4 weeks.Provenzano et al. (58) found that an in-creased dosing interval from weekly toonce monthly using epoetin- in dosesup to 40,000 units maintained Hb in asimilar range.

Extended dosing of short- and long-

acting ESA, including the hematopoieticand adverse effects, has recently been re-viewed (59). Currently, the only ESA ap-proved by the FDA for extended intervaldosing is darbepoetin. In clinical practice,darbepoetin is often administered everyother week initially, until the Hb targetis achieved, before extending dosing toevery 4 weeks. Extended dosing mayrequire an increase in dose (27,57).

Monitoring response to treatment

Patients should be evaluated for improve-ment in symptoms including fatigue, vi-tality, physical functioning, and cognitivefunction. Initially, Hb level should bemeasured every other week to monitorthe hematopoietic response and monthlythereafter. In general, if an Hb level devi-ates from the target range (see above), thedose of the ESA should be adjusted eitherupward or downward by 25%. In mostpatients, increases or decreases in ESAdose should not be made more frequentlythan monthly. Also, for safety reasons, ifHb is rising at a rate of1 g/dl within a4-week period, the dose should be held,as more rapid increases may be associatedwith increased risk for adverse eventssuch as hypertension.

Functional iron deficiency should besuspected in any patient not respondingto ESA treatment, and patient compliancewith iron therapy should be investigated.Routine measurement of iron stores in-cluding serum iron, iron binding capac-ity, and ferritin should be monitoredmonthly for 3 months then quarterly onceHb target is achieved (56,60).

Adverse side effects of therapyIn clinical trials, up to 25% of patientsexperience an increase in blood pressureor develop overt hypertension (bloodpressure 140/90 mmHg) (8,27,47,6163). Thus, ESA should not be used to treatanemia in patients with uncontrolledblood pressure. Moreover, increases in

blood pressure should be looked for inany anemic CKD patient treated with anESA, and dose adjustments in ESA, iron,or antihypertension medications shouldbe undertaken as needed. Common sideeffects include local pain or tissue reac-tion to subcutaneous injection and devel-opment of flu-like symptoms withinhours or days of administration of an ESA.

A rare but serious form of pure redcell aplasia can occur during ESA treat-ment, including in those treated with epo-etin and darbepoetin (64,65). The anemia

is sudden in onset and can occur as earlyas 2 months after initiation of treatment.As noted above, ESA may increase risk fordeath and cardiovascular events andthrombotic events. The risk is reported inthose with Hb levels 12 g/dl in someclinical trials. Therefore, it is prudent tomodify the dose of ESA to reduce the like-lihood of excursions of Hb exceeding 13g/dl as recommended by the NKF (51).

Adverse effects of iron use are describedabove and include gastrointestinal side ef-fects with oral preparations and anaphy-la c t ic re a c t ions wit h int ra ve nous

preparations.

AREAS OF

UNCERTAINTY Analysis of avail-able evidence from clinical trials clearlyindicates that there is enough uncertaintyregarding the risk-to-benefit ratio of treat-ment of anemic CKD patients with ESA towarrant additional major randomizedclinical trials (66). TREAT is an ongoingstudy that will provide additional new in-formation on whether treatment per secan improve cardiovascular outcomes in

patients with type 2 diabetes, anemia, andCKD (50). Because nearly 50% of newcases of ESRO in the U.S. are attributed todiabetes, further studies are needed tohelp guide management of anemia. Areasof uncertainty that remain include estab-lishment of the optimal individual Hblevelthe level at which patient QOL ismaximized and morbidity and mortalityrisks are minimized. The optimal dose ofa given ESA, the frequency of dosing, andthe indication and target Hb range remaincontroversial. For example, should ESAdosing begin at an Hb level of 10, 11, or

12 g/dl? Another area of uncertainty con-cerns the diagnosis and management oferythropoietin hyporesponsiveness, forwhich there is no widely accepted, stan-dardized definition. This confounds theanalysis of clinical trials in which higherdoses of ESA and higher Hb occur inthose randomized to higher Hb targets.

Additional studies are needed to under-stand the nature and extent of hypo-responsiveness to erythropoietin inpatients with CKDan area of high pri-ority for future research. However, it isnot established whether the benefits ofimproved QOL measures outweigh therisks of cardiovascular morbidity andthe economic costs related to treatmentto achieve a higher Hb level. Anotherarea of uncertainty related to hypo-responsiveness is the role of iron use intreating anemia. New research that pro-vides a better understanding of the roleof inflammation in iron metabolism,utilization, and the response to ESAtreatment is another important researchpriority.

SUMMARY Anemia is commonand contributes to both poor QOL andincreased risk for adverse outcomes in-cluding death. Treatment of anemia im-proves QOL; however, thus far, evidence

is lacking for a benefit of anemia treat-ment on progression of kidney diseaseand cardiovascular outcomes. The NKFrecommends that physicians considertreating anemia in patients with diabetesand kidney disease when Hb is 11 g/dlin patients. Further, they recommend aHb target of 1112 g/dl, not to exceed 13g/dl, when using an ESA as part of thetherapeutic regimen for managing ane-mia. Currently available ESA combinedwith iron supplementation can be usedsafely and effectively to achieve this goal.

However, available clinical trial evidenceleaves sufficient uncertainty regarding theoptimal Hb target and ESA dose for agiven individual. For this reason, the NKFrecommends individualizing treatment ofanemia with ESA. Additional randomizedclinical trials are needed to more preciselydefine these parameters for an individualpatient. Future studies are also needed toelaborate the mechanisms of anemia inpatients with diabetes and CKD includingthe role of iron metabolism, inflamma-tion, and resistance.

Anemia, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease

1324 DIABETESCARE, VOLUME32, NUMBER7, JULY2009

-

7/25/2019 Anemia, Diaetes and Chronic Kidney Disease

6/7

Acknowledgments This work was sup-ported in part by National Institutes of HealthGrant 5-K24-DK002818-05.

R.D.T. serves as an investigator in TREAT,an Amgen-sponsored clinical trial seeking toreduce end points with Aranesp therapy. Noother potential conflicts of interest relevant tothis article were reported.

References1. USRDS. United States Renal Data Systems

Annual Data Report. Am J Kid Dis 2007;49(Suppl. 1):S10S294

2. Herzog CA, Mangrum JM, Passman R.Sudden cardiac death and dialysis pa-tients. Semin Dial 2008;21:300307

3. Vlagopoulos PT, Tighiouart H, WeinerDE, Griffith J, Pettitt D, Salem DN, LeveyAS, Sarnak MJ. Anemia as a risk factor forcardiovascular disease and all-cause mor-tality in diabetes: the impact of chronic

kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2005;16:340334104. Toto RD. Heart disease in diabetic pa-

tients. Semin Nephrol 2005;25:3723785. New JP, Aung T, Baker PG, Yongsheng

G, Pylypczuk R, Houghton J, RudenskiA, New RP, Hegarty J, Gibson JM,ODonoghue DJ, Buchan IE. The highprevalence of unrecognized anaemia inpatients with diabetes and chronic kidneydisease: a population-based study. DiabetMed 2008;25:564569

6. Drueke TB, Locatelli F, Clyne N, EckardtKU, Macdougall IC, Tsakiris D, BurgerHU, Scherhag A, the CREATE Investiga-

tors. Normalization of Hb level in patientswith chronic kidney disease and anemia.N Engl J Med 2006;355:20712084

7. Mohanram A, Zhang Z, Shahinfar S,Keane WF,Brenner BM,Toto RD.Anemiaand end-stage renal disease in patientswith type 2 diabetes and nephropathy.Kidney Int 2004;66:11311138

8. Levin A, Djurdjev O, Thompson C, Bar-rett B, Ethier J, Carlisle E, Barre P, MagnerP, Muirhead N, Tobe S, Tam P, Wadgy-mar JA, Kappel J, Holland D, Pichette V,Shoker A, Soltys G, Verrelli M, Singer J.Canadian randomized trial of Hb mainte-nance to prevent or delay left ventricular

mass growth in patients with CKD. Am JKidney Dis 2005;46:799811

9. Roger SD, McMahon LP, Clarkson A, Dis-ney A, Harris D, Hawley C, Healy H, KerrP, Lynn K, Parnham A, Pascoe R, Voss D,Walker R, Levin A. Effects of early and lateintervention with epoetin alpha on leftventricular mass among patients withchronic kidney disease (stage 3 or 4): re-sults of a randomized clinical trial. J AmSoc Nephrol 2004;15:148156

10. Horl WH, Vanrenterghem Y, Canaud B,Mann J, Teatini U, Wanner C, WikstromB. Optimal treatment of renal anaemia(OPTA): improving the efficacy and effi-

ciency of renal anaemia therapy in hae-modialysis patients receiving intravenousepoetin. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2005;20(Suppl. 3):iii25iii32

11. Singh AK, Szczech L, Tang KL, BarnhartH, Sapp S, Wolfson M, Reddan D, theCHOIR Investigators. Correction of ane-mia with epoetin alfa in chronic kidneydisease. N Engl J Med 2006;355:2085

209812. Fishbane S, Nissenson AR. The new FDA

label for erythropoietin treatment: howdoes it affect Hb target? Kidney Int 2007;72:806813

13. Macdougall IC, Eckardt KU, Locatelli F.Latest US KDOQI Anaemia Guidelinesupdatewhat are the implications for Eu-rope? Nephrol Dial Transplant 2007;22:27382742

14. Astor BC, Muntner P, Levin A, Eustace JA,Coresh J. Association of kidney functionwith anemia: theThirdNationalHealth andNutrition Examination Survey (1988-1994). Arch Intern Med 2002;162:1401-1408

15. Thomas MC. Anemia in diabetes: markeror mediator of microvascular disease? NatClin Pract Nephrol 2007;3:2030

16. Thomas MC, Tsalamandris C, MacIsaacRJ, Jerums G. The epidemiology of Hblevels in patients with type 2 diabetes.Am J Kidney Dis 2006;48:537545

17. Fishbane S, Pollack S, Feldman HI, JoffeMM. Iron indices in chronic kidney dis-ease in the National Health and Nutri-tional Examination Survey 19882004.Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009;4:5761

18. Mezzano S, Droguett A, Burgos ME, Ar-

diles LG,Flores CA,ArosCA, CaorsiI, VoCP, Ruiz-Ortega M, Egido J. Renin-angio-tensin system activation and interstitialinflammation in human diabetic ne-phropathy. Kidney Int 2003;(Suppl):S64S70

19. Thomas MC, MacIsaac RJ, TsalamandrisC, Jerums G. Elevated iron indices in pa-tients with diabetes. Diabet Med 2004;21:798802

20. Erslev AJ, Besarab A. Erythropoietin inthe pathogenesis and treatment of theanemia of chronic renal failure. KidneyInt 1997;51:622630

21. Winkler AS, Marsden J, Chaudhuri KR,

Hambley H, Watkins PJ. Erythropoietindepletion and anaemia in diabetes melli-tus. Diabet Med 1999;16:813819

22. Bosman DR, Winkler AS, Marsden JT,Macdougall IC, Watkins PJ. Anemia witherythropoietin deficiency occurs early indiabetic nephropathy. Diabetes Care2001;24:495499

23. Howard RL, Buddington B, Alfrey AC.Urinary albumin, transferrin and iron ex-cretion in diabetic patients. Kidney Int1991;40:923926

24. Vaziri ND. Erythropoietin and transferrinmetabolism in nephrotic syndrome. Am JKidney Dis 2001;38:18

25. Marathias KP, Agroyannis B, Mavro-moustakos T, Matsoukas J, Vlahakos DV.Hematocrit-lowering effect following in-activation of renin-angiotensin systemwith angiotensin converting enzyme in-hibitors and angiotensin receptor block-ers. Curr Top Med Chem 2004;4:483486

26. Mohanram A, Zhang Z, Shahinfar S, Lyle

PA, Toto RD. The effect of losartan on Hbconcentration and renal outcome in dia-betic nephropathy of type 2 diabetes. Kid-ney Int 2008;73:630 636

27. TotoRD, Pichette V, Navarro J, Brenner R,Carroll W, Liu W, Roger S. Darbepoetinalfa effectively treats anemia in patientswith chronic kidney disease with de novoevery-other-week administration. Am JNephrol 2004;24:453460

28. Rossert J, Froissart M. Role of anemia inprogression of chronic kidney disease. Se-min Nephrol 2006;26:283289

29. Mohanram A, Toto RD. Outcome studiesin diabetic nephropathy. Semin Nephrol2003;23:255271

30. Norman JT, Fine LG. Intrarenal oxygen-ation in chronic renal failure. Clin ExpPharmacol Physiol 2006;33:989996

31. Iwano M, Neilson EG. Mechanisms of tu-bulointerstitial fibrosis. Curr Opin Neph-rol Hypertens 2004;13:279284

32. Garcia DL, Anderson S, Rennke HG,Brenner BM. Anemia lessens and its pre-vention with recombinant human eryth-ropoietin worsens glomerular injury andhypertension in rats with reduced renalmass. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1988;85:61426146

33. Lafferty HM, Anderson S, Brenner BM.Anemia: a potent modulator of renal he-modynamics in models of progressive re-nal disease. Am J Kidney Dis 1991;17(Suppl. 1):27

34. Nakamura T, Sugaya T, Kawagoe Y, Su-zuki T, Ueda Y, Koide H. Effect of eryth-ropoietin on urinary liver-type fatty-acid-binding protein in patients with chronicrenal failure and anemia. Am J Nephrol2006;26:276280

35. Keith DS, Nichols GA, Gullion CM,Brown JB, Smith DH. Longitudinal fol-low-up and outcomes among a popula-tion with chronic kidney disease in a large

managed care organization. Arch InternMed 2004;164:659 663

36. Herzog CA, Puumala M, Collins AJ.NHANES III: the distribution of Hb levelsrelated to chronic kidney disease (CKD),diabetes (DM), and congestive heart fail-ure (CHF) (Abstract). J Am Soc Nephrol2002;13:428A

37. Collins AJ, Li S, Gilbertson DT, Liu J,Chen SC,Herzog CA.Chronickidney dis-ease and cardiovascular disease in theMedicare population. Kidney Int 2003(Suppl):S24S31

38. Burrows L, Muller R. Chronic kidney dis-ease and cardiovascular disease: patho-

Mehdi and Toto

DIABETESCARE, VOLUME 32, NUMBER7, JULY2009 1325

-

7/25/2019 Anemia, Diaetes and Chronic Kidney Disease

7/7

physiologic links. Nephrol Nurs J 2007;34:5563

39. Foley RN, Parfrey PS, Sarnak MJ. Epide-miology of cardiovascular disease inchronic renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol1998;9(Suppl.):S16S23

40. Levin A. Identification of patients and riskfactors in chronic kidney diseaseevalu-ating risk factors and therapeutic strate-

gies. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2001;16(Suppl.):5760

41. McClellan WM, Jurkovitz C, Abramson J.The epidemiology and control of anaemiaamong pre-ESRD patients with chronickidney disease. Eur J Clin Invest 2005;35(Suppl. 3):58 65

42. Silverberg DS, Wexler D, Iaina A,Schwartz D. The interaction betweenheart failure and other heart diseases, re-nal failure, and anemia. Semin Nephrol2006;26:296306

43. Astor BC, Arnett DK, Brown A, Coresh J.Association of kidney function and Hbwith left ventricular morphology amongAfrican Americans: the AtherosclerosisRisk in Communities (ARIC) study. Am JKidney Dis 2004;43:836845

44. Joss N, Patel R, Paterson K, Simpson K,Perry C, Stirling C. Anaemia is commonand predicts mortality in diabetic ne-phropathy. Q J Med 2007;100:641647

45. Kuriyama S, Tomonari H, Yoshida H,Hashimoto T, Kawaguchi Y, Sakai O. Re-versal of anemia by erythropoietin ther-apy retards the progression of chronicrenal failure, especially in nondiabetic pa-tients. Nephron 1997;77:176185

46. Gouva C, Nikolopoulos P, Ioannidis JP,Siamopoulos KC. Treating anemia earlyin renal failure patients slows the declineof renal function: a randomized con-trolled trial. Kidney Int 2004;66:753-760

47. Rossert J, Levin A, Roger SD, Horl WH,FouquerayB, Gassmann-Mayer C, Frei D,McClellan WM. Effect of early correctionof anemia on the progression of CKD.Am J Kidney Dis 2006;47:738750

48. Ritz E, Laville M, BilousRW, ODonoghue

D, Scherhag A, Burger U, de Alvaro F;Anemia Correction in Diabetes Study In-vestigators. Target level for Hb correctionin patients with diabetes and CKD: pri-mary results of the Anemia Correction inDiabetes (ACORD) Study. Am J KidneyDis 2007;49:194207

49. Szczech LA, Barnhart HX, Inrig JK, Red-dan DN, Sapp S, Califf RM, Patel UD,

Singh AK. Secondary analysis of theCHOIR trial epoetin-alpha dose andachieved Hb outcomes. Kidney Int 2008;74:791798

50. Mix TC, Brenner RM, Cooper ME, deZeeuw D, Ivanovich P, Levey AS, McGillJB, McMurray JJ, Parfrey PS, Parving HH,Pereira BJ, Remuzzi G, Singh AK, So-lomon SD, Stehman-Breen C, Toto RD,Pfeffer MA. RationaleTrial to ReduceCardiovascular Events with AranespTherapy (TREAT): evolving the manage-ment of cardiovascular risk in patientswith chronic kidney disease. Am Heart J2005;149:408413

51. KDOQI. Clinical practice guideline andclinical practice recommendations foranemia in chronic kidney disease: 2007update of Hb target. Am J Kidney Dis2007;50:471530

52. FDA/Center for Drug Evaluation and Re-search: Erythropoiesis-stimulating agents(ESAs): epoetin alfa (marketed as Pro-crit, Epogen), darbepoetin alfa (mar-keted as Aranesp) [article online], 2007.Available from http://www.fda.gov/cder/drug/advisory/RHE200711.htm. Accessed1 April 2008

53. Fishbane S, Besarab A. Mechanism of in-creased mortality risk with erythropoietintreatment to higher Hb targets. Clin J AmSoc Nephrol 2007;2:12741282

54. Dahdah K, Patrie JT, Bolton WK. Intrave-nous iron dextran treatment in predialysispatients with chronic renal failure. Am JKidney Dis 2000;36:775782

55. Van Wyck DB, Roppolo M, Martinez CO,Mazey RM, McMurray S. A randomized,controlled trial comparing IV iron sucroseto oral iron in anemic patients with non-

dialysis-dependent CKD. Kidney Int2005;68:28462856

56. Fishbane S. Iron management in nondi-alysis-dependent CKD. Am J Kidney Dis2007;49:736743

57. Ling B, Walczyk M, Agarwal A, Carroll W,Liu W, Brenner R. Darbepoetin alfa ad-ministered once monthly maintains Hb

concentrations in patients with chronickidney disease. Clin Nephrol 2005;63:327334

58. Provenzano R, Bhaduri S, Singh AK. Ex-tended epoetin alfa dosing as mainte-nance treatment for the anemia of chronickidney disease: the PROMPT study. ClinNephrol 2005;64:113123

59. Carrera F, Disney A, Molina M. Extendeddosing intervals with erythropoiesis-stim-ulating agentsin chronic kidney disease: areview of clinical data. Nephrol DialTransplant 2007;22(Suppl. 4):iv19iv30

60. Fishbane S. Safety in iron management.Am J Kidney Dis 2003;4(Suppl. 5):1826

61. Strippoli GF, Craig JC, Manno C, SchenaFP. Hb targets for the anemia of chronickidney disease: a meta-analysis of ran-domized, controlled trials. J Am SocNephrol 2004;15:31543165

62. Aranesp (darbepoetin alfa) for injection [arti-cle online]. Available from http://www.aranesp.com/pdf/aranesp_pi.pdf. Accessed 1April 2008

63. Procrit (epoitin alfa): for injection [article on-line].Available from http://www.procrit.com/procrit/shared/OBI/PI/ProcritBooklet.pdf#page1. Accessed 1 April 2008

64. Howman R, Kulkarni H. Antibody-medi-

atedacquiredpure redcell aplasia (PRCA)after treatment with darbepoetin. Neph-rol Dial Transplant 2007;22:14621464

65. Rossert J, Froissart M, Jacquot C. Anemiamanagement and chronic renal failureprogression. Kidney Int 2005;(Suppl):S76S81

66. Parfrey PS. Target Hb level for EPO ther-apy in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 2006;47:171173

Anemia, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease

1326 DIABETESCARE, VOLUME32, NUMBER7, JULY2009