Anderson - A Bipartite Patella in a Juvenile From a Medieval Context

-

Upload

dragana-vulovic -

Category

Documents

-

view

212 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Anderson - A Bipartite Patella in a Juvenile From a Medieval Context

-

International Journal of OsteoarchaeologyInt. J. Osteoarchaeol. 12: 297302 (2002)Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI: 10.1002/oa.600

SHORT REPORT

A Bipartite Patella in a Juvenile from aMedieval ContextT. ANDERSON*Vichy House, 15 St Marys Street, Canterbury, Kent, UK

ABSTRACT One hundred and thirty six well-preserved medieval skeletons were excavated in advance ofre-development in Norwich. The right patella of a 1315 year old skeleton (SK 65) displays afracture line running through the supero-lateral pole. This represents the fusion of a secondaryossification centre, a condition known as bipartite patella. It should not be confused with otheranatomical variants or with pathological processes. Copyright 2002 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Key words: bipartite patella; vastus notch; emargination; dorsal defect; double patella; patellarfracture; anatomical variant; medieval Norwich

Introduction

Archaeological investigation at St Faiths Lane,Norwich uncovered a cemetery associated withthe Franciscan friary. One hundred and thirty sixwell-preserved skeletons, dating from the 13th tothe 16th century, were recovered. The exclusionof all children under the age of eight years and thepaucity of adult females, suggests that it was nota lay cemetery. Similar high frequencies of malesand a lack of children have been noted at othermedieval monastic sites (Anderson & Andrews,2001: Tables 57 and 58).

The detailed osteological report for this siteis about to be published (Anderson et al., 2002).This short note is to draw attention to a conditionwhich has been rarely noted in the archaeo-osteological literature, namely an incompletelyfused bipartite patella. This is an anatomical vari-ant which might possibly be confused with ahealing fracture. Or, if present in an archaeologi-cal context as a completely separate element, theloose ossicle may not be recognized as being ofhuman origin.

* Correspondence to: Vichy House, 15 St Marys Street, Canterbury,Kent CT1 2QL.

The material

The involved skeleton (SK 65) is incomplete,the left side has been cut away by a later grave(SK 29). The right arm, ilium, and leg as wellas both feet are solid and well-preserved. Anincomplete right scapula and right rib fragmentswere also recovered. The lower two lumbarvertebrae, upper sacral fragment, left scapula andrib fragments, left humerus, radius, ilium, distalfemoral epiphysis and tibia were also recoveredas disarticulated material in the gravefill of SK 29.All available epiphyses, including the right elbow,were unfused. Age, was assessed as 1315 years,based on diaphyseal length of the right femur andtibia (Ferembach et al., 1980).

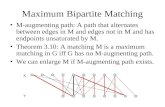

The only anomaly is a concave fracture linelocated at the supero-lateral pole of the rightpatella (Figure 1). The borders of the defectare porous and slightly roughened. Anteriorly,the ossicle is partially separated by a deep fis-sure with interdigitating margins. Posteriorly,the ossicle is united to the main patellar bodywith only a fine concave hair-line crack vis-ible. The left patella was not available forexamination.

Copyright 2002 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Received 17 January 2001Revised 10 February 2001Accepted 13 March 2001

-

298 T. Anderson

Figure 1. The right patella of a 1315 year old (SK 65) displaying a fracture line running through the supero-lateral pole. Thisrepresents the partial fusion of a secondary ossification centre, a condition known as bipartite patella (scale in cm).

Diagnosis

A porous, rough-edged defect at this loca-tion, first described by Wenzel Gruber in1883, is known as a bipartite patella (Gru-ber, 1883). It represents an anatomical vari-ant, a separate accessory fusion centre whichremains as a separate ossicle or multipleossicles at the superolateral patellar border(Figure 2: III).

Examples have been reported in the old clinicalliterature (Wright, 1904; Adams & Leonard,1925; George, 1935; Shulman, 1955). It isrecognized as an anatomical variant in the modernorthopaedic and radiological literature (Resnick &Niwayama, 1981: Fig 2058; Tachdjian, 1990:620; Duthie & Bentley, 1996: 1167; Silverman& Kuhn, 1993: fig 43.86). It has occasionallybeen referred to in the osteo-archaeologicalcontext (Finnegan, 1978; Mann & Murphy,1990: 118120, Figure 78a; Scheuer & Black,2000: 397).

The resultant ossicle may remain separate, fuseincompletely (as in this case) or totally re-unitewith the main bone, which will result in a normalpatella (Green, 1975). In Saupes tripartite clas-sification, such supero-lateral bipartition (75%)was the most frequent occurrence (Saupe, 1943).However, rarer forms of patella bipartition mayoccur at other sites (Figure 2) (Schaer, 1934; Kern& Rodriguez, 1988). Each type of bipartition is dis-cussed below, as is the confusion of terminologyin the older literature.

Differential diagnosis

Defects involving the supero-lateral border

a) Vastus notchThis anatomical variant occurs in the supero-

lateral pole of the patella (Finnegan, 1978; Mann& Murphy, 1990: 120, Figure 78e). However, itcan be distinguished from a bipartite patella by

Copyright 2002 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 12: 297302 (2002)

-

A Bipartite Patella in a Juvenile 299

Figure 2. Variation in patellar bipartitions (after Schaer, 1934; Kern & Rodriguez, 1988). Reproduced by Permission of Hans HuberPublishers.

the fact that it is smooth-edged (Mann & Murphy,1990: 120). It may occur as a slight or a deep,marked concavity and is the result of variationin the site of the vastus lateralis (Oetteking, 1922;Finnegan, 1978; Mann & Murphy, 1990: 120, Fig78a). The spinous process, occasionally found atthe inferior margin of the notch, marks the lowerlimit of the tendon (Oetteking, 1922). Slightexpression of the variant is a common finding(Mann & Murphy, 1990: 120; Scheuer & Black,2000: 397). Well-developed notches were notedin 6.1% (23/375) of all patellae from medievalCanterbury, with males involved more frequently,9.4% (17/180), than females 4.1% (6/148) (authorunpublished work).

b) Emargination of the patellaThis term, meaning removal of the margin,

was first used by Kempson for defects of thesupero-lateral patellar border (Kempson, 1902).The description of a smooth concave depressionwith a slight tubercle at the upper limit and a sharpprocess at the lower margin clearly equates withthe anomaly which today is known as a vastusnotch (Mann & Murphy, 1990: 120; Scheuer &Black, 2000: 397).

Several workers have used the term emargina-tion to describe smooth-edged examples of vastus

notch (Wright, 1904; George, 1935: Fig. 385).Unfortunately, other authors have referred toboth vastus notch (a variation in tendon inser-tion) and supero-lateral ossicle (a persistentsupernumerary ossification centre) as examplesof emargination (Todd & McCally, 1921; Oet-teking, 1922). Consequently, earlier examplesof emargination must be treated with cau-tion. The two aetiologically dissimilar conditionsshould be identified either as vastus notch oras a bipartite patella (Mann & Murphy, 1990:118120).

c) Dorsal defect of the patellaA defect occurs on the supero-lateral pole of

the patella in c. 1% of the population (Johnson &Brogdon, 1982). It may be related to mechanicalstress (Sutton, 1998: 1632) or a variant inossification (Resnick & Niwayama, 1981: 728) andappears to be self-limiting (Resnick& Niwayama,1981: 728). It can be separated from a bipartitepatella since it is present as a cavitation, orpunched out depression, on the articular (dorsal)surface (Todd & McCally, 1921: Fig. 7; Owsley &Mann, 1990). It may occur in conjunction withbipartite patella, or as a separate anomaly (Todd& McCally, 1921).

Copyright 2002 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 12: 297302 (2002)

-

300 T. Anderson

Defects at other locations

a) TraumaWhen both patellae are available for examina-

tion it is worth remembering that traumatic injurywould almost invariably be unilateral, whereasan anatomical variant would frequently be bilat-eral. Also, a direct blow to the periphery ofthe bone would normally cause avulsion of thelateral aspect of the patella (Figure 2: II) (Tachd-jian, 1990: 3284). This equates with Saupessecond most frequent bipartition (20%) (Saupe,1943).

In the present case, there is no new boneovergrowth or callus formation that one mightexpect with a healing fracture. Also, due to themobility of the sub-adult bone, childhood patellarfractures are not common (Tachdjian, 1990:3284). A stress fracture would typically presentas either a complete transverse or supero-inferiormid-patellar fissure (Devas, 1960). The fact thatthe ossicle is re-united with no displacementdoes not argue for fracture of the cartilaginousjunction between an additional ossicle and thenormal patella (Green, 1975). In rare cases, alateral fracture may be found in association withadditional ossicles (Figure 2: II and III).

An accessory ossicle may occur at the inferiorpole of the patella (Figure 2: I) (Paus, 1926: Fig1). This equates with Saupes rare bipartition(5%) (Saupe, 1943). However, it is perhaps betterconsidered as a form of fracture, possibly a tractionepiphysitis, whose development may be related tovigorous exercise during adolescence (Medlar &Lyne, 1978), including sporting activities such ashurdling (Resnick & Niwayama, 1981: Table 63-1). An archaeological example has just beenpublished from the late Roman cemetery atCannington. Somerset (Brothwell et al., 2000:Fig 153).

b) Double patella

The term double patella should only be usedfor the condition in which the bone is separatedinto a superior and inferior portion, frequentlywith partial overlap (Figure 2: V). The superiorportion is normally larger and, if it completelyoverlaps the smaller element, the result is an

anterior and posterior patella (Brailsford, 1945:Figure 146b).

It is an extremely rare condition in man but mayoccur as part of the genetic condition multipleepiphyseal dysplasia (MED) (Silverman & Kuhn,1993: 1632, Figure 43.86; Sutton, 1998: 2223,Figure 1.49). However, MED would occur withthe late development, reduced size and irregularmineralization of numerous epiphyses, with thehip, shoulder and ankle frequently involved(Sutton, 1998: 23).

c) Additional ossicle located mediallyAn accessory, medially located, ossicle is an

extremely rare (occurrence) (Figure 2: IV). Itappears to represent an unfused additional ossi-fication centre, similar to the present case ofbipartite patella (Figure 2: III), but located on themedial border of the patella. Only the symp-tomatic cases will be reported in clinical literature(Halpern & Oakley, 1978).

Discussion

In the present case, the ossicle has startedto fuse to the main patellar body. Such acoalescence, during growth, has been noted bymany workers (Adams & Leonard, 1925: Nevasier,1931; George, 1935). It is possible that theaccessory ossification centre may fail to fusedue to stress (Oetteking, 1922) or repeatedmicrotrauma (Todd & McCally, 1921; Green,1975).

Green (1975) states that 15% of patellae maydevelop from a double ossification centre, but only140% remain as independent ossicles. Basedon these figures, the prevalence of persistentbipartition is 0.26.0% (Green, 1975). Otherworkers state that bipartite patellae may affect13% of the population (Todd & McCally, 1921;Adams & Leonard, 1925; Tachdjian, 1990: 3284;Aufderheide & Rodriguez-Martin, 1998: 74).

Since bipartitions are largely sub-clinical(Green, 1975), with perhaps only 2% of casesgiving rise to symptoms (Weaver, 1977), thetrue prevalence is uncertain. Clinical data sug-gest that bipartition is much more frequent inmales than in females (9:1 Green, 1975). How-ever, this apparent dimorphism may be biased by

Copyright 2002 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 12: 297302 (2002)

-

A Bipartite Patella in a Juvenile 301

greater numbers of males receiving knee injuriesand, therefore, the subsequent discovery of theanomaly is an incidental finding at radiographicexamination.

In archaeological samples the bipartite patellahas rarely been reported (Baudounin, 1935; Wells,1981; Zammit, 1983). In a large sample ofmedieval skeletons from Canterbury only oneunaged adult male had the condition. (authorunpublished work). To date, the highest fre-quency (8%) has been found in a CanadianIroquois ossuary dated to c. 1400 AD (Anderson,1964: 52).

References

Adams JD, Leonard RD. 1925. A developmentalanomaly of the patella frequently diagnosed as frac-ture. Surgical Gynaecological Obstetrics 41: 601604.

Anderson JE. 1964. The people of Fairty: an osteo-logical analysis of an Iroquois ossuary. Bulletin of theNational Museum of Canada 193: 28129.

Anderson T, Andrews J. 2001. The human remains.In St Gregorys Priory Northgate, Canterbury. Excavations19881991, Hicks M, Hicks A. Canterbury Archae-ological Trust Ltd: Canterbury. 338370.

Anderson T, McMullen Willis E, Andrews J, Hod-gins I. 2002. The human skeletel material in: SodenI. Life andDeath on aNorwich Backstreet c. 9001600A.D.Northamptonshire Archaeology Report: Northamp-ton.

Aufderheide AC, Rodriguez-Martin C. 1998. The Cam-bridge Encyclopedia of Human Paleopathology. CambridgeUniversity Press: Cambridge; 74.

Baudounin M. 1935. Une lesion inconnue de la rotulechez un prehistorique. Paris Medical 1: 69.

Brailsford JF. 1945. The Radiology of Bone and Joints. J & AChurchill: London.

Brothwell DR, Powers R, Hirst SM. 2000. The Pathol-ogy. in: Rahtz P. Hirst S. Wright SM. CanningtonCemetery. Society for the Promotion of Roman Stud-ies, English Heritage: Britannia Monograph SeriesNo. 17: London.

Devas MB. 1960. Stress fracture of the patella. Journalof Bone and Joint Surgery 42B: 7174.

Duthie RB, Bentley G. (editors). 1996. MercersOrthopaedic Surgery. (9th edition) Arnold: London.

Ferembach D, Schwidetzky I, Stloukal M. 1980. Rec-ommendations for age and sex diagnoses of skele-tons. Journal of Human Evolution 9: 517549.

Finnegan M. 1978. Non metric variation of the infracranial skeleton. Journal of Anatomy 125: 2337.

George R. 1935. Bilateral bipartite patellae. BritishJournal of Surgery 22: 555560.

Green LT (jr). 1975. Painful bipartite patellae a casereport of three cases. Clinical Orthopaedics and RelatedResearch 110: 197200.

Gruber W. 1883. In Bildungsanomalie mit Bildung-shemmung begrundete Bipartition beider Patel-lae eines jungen Subjektes. Virchows Archive 94:358361.

Halpern AA, Oakley H. 1978. Painful medial bipartitepatellae. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 134:180181.

Johnson JF, Brogdon BG. 1982. Dorsal defects ofthe patella. American Journal of Roentgenology 139:339340.

Kempson FC. 1902. Emargination of the patella. Journalof Anatomy 36: 419420.

Kern S, Rodriguez M. 1988. Die Patella partita. Shweiz-erische Rundschau fur Medizin (PRAXIS) 77(31/32):820825.

Mann RW, Murphy SP. 1990. Regional Atlas of BoneDisease. CC Thomas: Springfield.

Medlar RC, Lyne ED. 1978. Sinding Larsen Johanssondisease. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 60A:11131116.

Nevasier JS. 1931. Bipartite patella. Annals of Surgery94: 150154.

Oetteking B. 1922. Anomalous patellae. AnatomicalRecord 23: 269279.

Owsley JW, Mann RW. 1990. Bilateral dorsal defectof the patella. American Journal of Roentgenology 154:13471348.

Paus N. 1926. Ein fall von patella bipartita. ActaChirugica Scandinavica 61: 4447.

Resnick D, Niwayama G. 1981. Diagnosis of Bone andJoint Disorders. WB Saunders: Philadelphia.

Saupe H. 1943. Primare Knochenmark seilerung derKniescheibe. Deutsche Zeitschrift fur Chirurgie 258: 386.

Schaer H. 1934. Die patella partita. Ergebnisse derChirurgie XXVII: 153.

Scheuer L, Black S. 2000.Developmental JuvenileOsteology.Academic Press: London.

Shulman S. 1955. Unilateral congenital duplication ofthe patella. British Journal of Radiology 28: 164165.

Silverman FN, Kuhn JP. 1993. Caffeys Pediatric X-RayDiagnosis: An Integrated Imaging Approach. (9th edition)Mosby: St Louis.

Sutton D. (editor). 1998. Textbook of Radiology andImaging. (6th edition) Churchill Livingstone: NewYork.

Tachdjian MO. 1990. PediatricOrthopedics. (2nd edition)WB Saunders: Philadelphia.

Todd TW, McCally CW. 1921. Defects of the patellarborder. Annals of Surgery 74: 775782.

Copyright 2002 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 12: 297302 (2002)

-

302 T. Anderson

Weaver JK. 1977. Bipartite patellae as a cause ofdisability in the athlete. American Journal of SportsMedicine 5: 137143.

Wells C. 1981. Discussion of the skeletal material. in:Reece R. Excavations in Iona 1964 to 1974. Institute ofArchaeology Occasional Publication No 5: Londonpp. 85101. (see p. 95 & Plate 9).

Wright W. 1904. A case of accessory patellae in thehuman subject with remarks on emargination of thepatellae. Journal of Anatomy 38: 6567.

Zammit J. 1983. Une exemple paleopathologique: lapartition rotulienne chez lhomme. Bulletin de la SocietePrehistorique Francaise 80: 1820.

Copyright 2002 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 12: 297302 (2002)