Anders Winroth - Classes*v2 : Gateway : Welcome Winroth For Robert Somerville, who first introduced...

Transcript of Anders Winroth - Classes*v2 : Gateway : Welcome Winroth For Robert Somerville, who first introduced...

I I I .

Where Gratian Slept: The Life and Death of the Father of Canon Law*)1

By

Anders Winroth

For Robert Somerville, who first introduced me to Master Gratian

We know very little about the life of the famous canonist Gratian, the author of the Decretum, except that he appeared as a legal adviser in Venice in 1143 and that he compiled at least some version of the Decretum. Abbot Robert of Torigni claimed in c. 1180 that Gratian was bishop of Chiusi, but since no other source supports this claim, there has been no reason to take it seriously. This article shows that a previously misinterpreted necrology from Siena proves that a bishop called Gratian in fact served in Chiusi at the middle of the twelfth century and that it is likely that the canonist Gratian stopped teaching in Bologna to become bishop in Chiusi. Some other aspects of Gratian’s biography are also examined.

Wir wissen nur wenig über das Leben des berühmten Kanonisten Gratian, den Autor des De-cretum, abgesehen von dem Umstand, dass er als Rechtsberater 1143 in Venedig war und dass er zumindest eine Rezension des Decretum erstellte. Abt Robert von Torigni behauptete 1180, dass Gratian Bischof von Chiusi war. Doch da keine andere Quelle diese Behauptung stützt, hat bislang kein Grund bestanden, Roberts Aussage ernst zu nehmen. Der vorliegende Beitrag zeigt, dass ein ursprünglich missverstandener Nekrolog aus Siena belegt, dass jemand namens Gratian tatsächlich in der Mitte des zwölften Jahrhunderts in Chiusi als Bischof wirkte. Es ist wahrschein-lich, dass der Kanonist Gratian seine Tätigkeit als Lehrer in Bologna beendete, um Bischof in Chiusi zu werden. Einige andere Fragen zur Biographie Gratians werden ebenfalls untersucht.

On the Tenth of August each year, Christians celebrate the martyrdom of St. Lawrence, as they have done for some seventeen centuries. But his mar-tyrdom is not the only death we may remember on that date. I want to invite

*) I thank my teacher Professor Robert Somerville and my students Dr. John Wei and Professor Eric Knibbs for commenting on drafts of this article and for advising me on specific issues. I also wish to thank the students in the workshop Law, Religion, and Society in Medieval Europe at Yale University for their valuable comments. The article goes back on a plenary lecture given at the XIVth International Congress of Medieval Canon Law in Toronto on 10 August 2012; I have chosen to retain some of the features of oral delivery apparent in the article.

2. KorreKtur

KA03_Winroth_Gratian.indd 105 07.04.2013 20:09:38

Anders Winroth106

you to celebrate also the passing of Master Gratian, the father of the science of canon law. He died on the Tenth of August at some point close to the middle of the twelfth century, I suspect in 1144 or 1145. When he died, he had retired from teaching in Bologna and he served as bishop of Chiusi in southern Tuscany. This is the main result of research that I have done on the biography of Gratian.

Anyone working on the life of Gratian needs to begin with a brilliant article by John T. Noonan published in 19791). Noonan did work that was urgently needed; he showed how scholars through the centuries had built up an image of Gratian that rested more on wishful thinking than on sound critical meth-ods. Standard reference works of the time claimed, for example, that Gratian was a Camaldolese monk, but that idea came from eighteenth-century his-torians of the Camaldolese order wishing to claim another famous alumnus, not from any medieval source. Noonan tore down the rickety biographical super-structure that had been constructed on top of the father of western canon law. What remained was Gratian, the author of at least parts of the Concordia discordantium canonum (the Decretum), who on the basis of that authorship could be said, according to Noonan’s elegant formulation, to be “a teacher with theological knowledge and interests and a lawyer’s point of view.” Gra-tian was also recorded as being in Venice in a document from 11432), but otherwise, Noonan found only “legend” and “unverified hearsay.” Noonan’s purpose was primarily to clean house, a much needed operation. He spent much less effort on attempting to say anything substantive about Gratian’s bi-ography, and he did not seek out any unprinted sources. This article contends that it is possible to get further than Noonan was able.

Noonan used sound historical methods, but he chose, as a distinguished professor of law and later a prominent judge, to couch his method in law-yerly terms, talking about hearsay and wanting to cross-examine witnesses. To make any headway with as complex and difficult a problem as Gratian’s biography, it will be important to cling a bit more closely than Noonan did to classical historical methodology and terminology, as they have been codi-fied from the late nineteenth century on3). Historical method distinguishes

1) John T. Noonan, Gratian Slept Here: The Changing Identity of the Father of the Systematic Study of Canon Law, in: Traditio 35 (1979), 145–172.

2) Andrea Glor ia , ed., Codice diplomatico padovano dall’anno 1101 alla pace di Costanza (= Deputazione veneta di storia patria Monumenti storici, ser. 1 Documenti 6), Venice 1879, 313–314.

3) Classical handbooks are Erns t Bernheim, Lehrbuch der historischen Methode und der Geschichtsphilosophie, eds. 5 and 6, New York 1970, and Char les Vic tor

2. KorreKtur

KA03_Winroth_Gratian.indd 106 07.04.2013 20:09:39

The Life and Death of Gratian 107

between sources that are themselves relics (Überreste) of historical events and those that are only narratives (Tradition) about those events. A relic is good evidence on its own if correctly understood, while one needs two independ-ent but consonant narratives to prove that they speak the truth. The discussion that follows will take this basic methodological insight as its starting point.

If we accept, as I think we must, that the first recension of the Decretum is a book written by Gratian, then the book itself is a relic of whatever Gratian was doing in composing it4). By studying the book, we get direct insight into Gratian’s work, obviously only insofar as we interpret it correctly. It is on such a basis that Noonan and others have been able to claim that Gratian was a teacher, and they are certainly correct. The work bears all the hallmarks of a teaching tool, perhaps most clearly in the formulations of the small stories that introduce each of the 36 Causae5). Further study of the text will reveal that Noonan was also correct in saying that Gratian was interested in theol-ogy and knew a lot about it. As I read the Decretum, I see more of the theo-logian than of the lawyer. Causa 13 is one of the more laywerly sections of the work with its concrete depiction of a court case, including plaintiff and defendant represented as arguing their respective sides6). After an introduc-tory Pseudo-Isidorian quotation, however, most of questio 1 consists of long chains of Biblical quotations (C.13, q.1, d.p.c.1), which continue in questio 2 (q.2, d.p.c.3). The lawyers in Gratian’s courtroom drama make arguments firmly based in their reading of the Bible; they are as much theologians as lawyers.

Gratian was not a dogmatic theologian, but rather a practical theologian who worried about the practical and concrete aspects of theological matters such as ordination, marriage, and clerical status. Interestingly, Gratian never in the first recension of his work addressed systematically some other im-portant matters of practical theology, such as baptism, confirmation, and the

Langlo is /Char les Se ignobos , Introduction aux études historiques, Paris 1992. These handbooks with their uncomplicated belief in “objectivity” and positivism are outdated (the editions referred above are modern reprints), but the methods they rec-ommend are still useful when attempting to explicate complicated source situations, as in this case. See also Mar tha C. Howel l /Wal te r Prevenier, From Reliable Sources: An Introduction to Historical Methods, Ithaca/N.Y. 2001.

4) Decretum magistri Gratiani, in: Emi l Fr iedberg , ed., Corpus iuris canonici, Leipzig 1879.

5) Anders Winro th , The Making of Gratian’s Decretum (= Cambridge studies in medieval life and thought, 4th ser., 49), Cambridge 2000, 7–8.

6) Freder ick S . Paxton , Le cause 13 de Gratien et la composition du Décret, in: Revue de droit canonique 51 (2001), 233–239.

2. KorreKtur

KA03_Winroth_Gratian.indd 107 07.04.2013 20:09:39

Anders Winroth108

consecretion of churches. The treatise De consecratione, which was a late addition to the work, examined that theology7).

One may be more specific about Gratian’s theology: he knew his Bible ex-tremely well. He framed many of the questions he posed in biblical terms, as when he told the story of David committing adultery with the already married beauty Bathsheba. David arranged for the death of her husband Uriah so that he could marry her. Was one thus, Gratian asked, permitted to marry a widow with whom one had committed adultery while her husband was alive8)? Obvi-ously, he answered in the negative, pointing out that much was permitted in the Old Testament that Christ had prohibited in the new dispensation.

The Bible is everywhere in the Decretum, even embedded in its structure. Most of the first part, the distinctions, in fact takes its organization from a few verses in St. Paul’s Letter to Timothy9). After the introductory section about the foundations of law, Gratian devoted the first part of the Decretum to ordination and church hierarchy. In what would later become distinctions 25–101, he treated rules about how a bishop, and by extension any cleric, should behave and what characteristics he should have. In so doing, Gratian quoted St. Paul’s First Letter to Timothy 3.1–6: “If a man desire the office of a bishop, he desires a good work. It behooves therefore a bishop to be blameless, the husband of one wife, sober, prudent, of good behavior, chaste, given to hospitality, a teacher, not given to wine, no striker, but modest, not quarrelsome, not covetous: but one that rules well his own house … not a neophyte”10). This list of desired and undesirable characteristics in a bishop provided Gratian with a ready-made structure that he was able to use in his work. He began in D. 25: “We shall carefully investigate of what sort he behooves to be who is going to be ordained a bishop, following the rule of the Apostle, which he for such a case wrote to Timothy and to Titus: ‘It be-

7) John Van Engen, Observations on De consecratione, in: Proceedings of the Sixth International Congress of Medieval Canon Law, S tephan Kut tner /Kenneth Pennington , edd. (= Monumenta iuris canonici C:7), Vatican City 1985, 309–320. I thank Professor Van Engen for discussing Gratian and his theology with me.

8) C.31, q.1, d.p.c.7. 9) Gabr ie l Le Bras , Les Écritures dans le Décret de Gratien, in: ZRG KA 27

(1938), 47–80.10) I Tim. 3.1–4,6. Note that Gratian’s Bible, like Alcuin’s edition, the common

medieval university bible, and the Sixto-Clementine Vulgate, contained the adjective pudicum (“chaste”), which was not present in Jerome’s original translation, see the standard hand edition, Rober t Weber, ed., Biblia sacra iuxta Vulgatam versionem, 4 ed. Stuttgart 1994, and the Nova vulgata, e.g., in Barbara Aland/Kur t Aland , edd., Novum Testamentum Graece et Latine, 4 ed. Stuttgart 2002.

2. KorreKtur

KA03_Winroth_Gratian.indd 108 07.04.2013 20:09:39

The Life and Death of Gratian 109

hooves a bishop to be blameless’”11). (Gratian also mentioned the Letter to Titus 1:6–8, since it repeats some of the same ideas as the Letter to Timothy, partially in the same words). After thus introducing the Letter to Timothy, Gratian quotes some legal statements that address and define the first ele-ment in St. Paul’s list, the idea that a bishop ought to be blameless.

Gratian then continues in D. 26 with “It follows in both letters: ‘the hus-band of a single wife’”12). For this characteristic, he has rather more law to quote and discuss, so the next element in St. Paul’s list, that a bishop should be sober, shows up only in D. 35: “It follows in that Apostolic description ‘that he be sober’ who is to be ordained”13). And so Gratian continues through most of the distinctions in the first part. What I want to emphasize by these observations (which were first made by Gabriel Le Bras) is that the Bible is deeply embedded in Gratian’s thinking, to the degree that it serves to organ-ize his thought.

The verse he chose to use as an organizing principle in his treatment of the law of ordination was, of course, eminently suitable for this purpose. It was a passage that had long been associated with the appointment of bishops, being regularly read in the liturgy at episcopal consecrations, and before cathedral chapters proceeded to elect a new bishop14). Thus, Gratian’s use of St. Paul’s words shows that he understands the traditions of the church from the inside, as it were. This evidence is not in itself strong enough to conclude that Gratian had practical experience as a cleric, but I have elsewhere argued that Gratian read the Bible and canon law as if he had an understanding of pastoral prob-lems15). Perhaps this means that Gratian was not only a professor of canon law, but someone with experience of the cure of souls.

11) D.25, d.p.c.3: “Ac primum a pontificali gradu incipientes qualem oporteat eum esse qui in episcopum ordinandus est, diligenter investigemus Apostoli regulam secuti, quam in huiusmodi re Timotheo et Tito scribit dicens ‘Oportet episcopum esse inrepre hensibilem,’ id est, ‘non obnoxium reprehensioni.’”

12) D.26, d.a.c.1: “Sequitur in utraque epistola: ‘unius uxoris virum.’”13) D.35, d.a.c.1: “Sequitur autem in descriptione illa apostolica: ‘ut sit sobrius’

qui ordinandus est, ‘non vinolentus.’”14) See, e. g., Edmond Mar tène , De antiquis Ecclesiæ ritibus libri tres, ed. novis-

sima Venice 1788, vol. 2, p. 55; Michel Andr ieu , Les ordines Romani du haut moy-en âge (= Spicilegium sacrum Lovaniense: Études et documents, 3), Louvain 1951, and Laur i tz Weibul l , ed., Necrologium Lundense: Lunds domkyrkas nekrologium (= Monumenta Scaniæ historica), Lund 1923, vol. 3, p. 612.

15) Anders Winro th , Marital consent in Gratian’s Decretum, in: Readers, Texts and Compilers in the Earlier Middle Ages: Studies in Medieval Canon Law in Honour of Linda Fowler-Magerl, Kath leen G. Cushing/Mar t in Bre t t , edd., Aldershot/

2. KorreKtur

KA03_Winroth_Gratian.indd 109 07.04.2013 20:09:39

Anders Winroth110

Gratian’s use of St. Paul for his organization is, incidentally, a well-nigh ir-refutable argument against the idea that the text of the Decretum known from the infamous manuscript St. Gall, Stiftsbibliothek 673 would be the earliest version of Gratian’s work16). This manuscript makes a hash of that organiza-tion, cutting most references to the Epistle to Timothy, while allowing a few to stand, orphaned and barely intelligible17). It is inconceivable that this was what Gratian first wrote.

Gratian’s use of St. Paul’s words shows not only that Gratian knew his Bible, but also that he knew the commentary tradition emanating from the eminent theologian Anselm of Laon that is known as the Glossa ordinaria to the Bible18). When Gratian, for example, introduced the first element in St. Paul’s list of suitable characteristics of a bishop, that he be blameless, he immediately added “that is, not subject to blame.” In doing so, Gratian was simply quoting an interlinear ordinary gloss to the Bible19). In the text that follows, he continues to quote bits and pieces of the Gloss to St. Paul’s Epistle to Timothy. This has all been carefully examined by Titus Lenherr, and it is not my purpose to restate his conclusions further20).

U.K. 2008. See also Jean Werckmeis te r, ed., Le mariage: Décret de Gratien, caus-es 27 à 36 (= Sources canoniques 3), Paris 2011, 71–73.

16) Car los Lar ra inzar, El borrador de la Concordia de Graciano: Sankt Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek MS 673 [= Sg], in: Ius ecclesiae 11 (1999), 593–666, argues that Sg was Gratian’s first draft. Kenneth Pennington , Gratian, Causa 19, and the Birth of Canonical Jurisprudence, in: Panta rei: Studi dedicati a Manlio Bellomo, Oraz io Condore l l i , ed., Rome 2004, supports this thesis. Strong and detailed textual argu-ments against the idea are presented in, e.g., Ti tus Lenher r, Die vier Fassungen von C. 3 q. 1 d. p. c. 6 im Decretum Gratiani: Zugleich ein Einblick in die neueste Diskussion um das Werden von Gratians Dekret, in: AKKR 169 (2000), 353–381; Anders Win-ro th , Recent work on the Making of Gratian’s Decretum, in: BMCL 26 (2004–2006), 1–29; Ti tus Lenher r, Zur Redaktionsgeschichte von C.23 q.5 in der ‚1. Rezension’ von Gratians Dekret: The Making of a Quaestio, in: BMCL 26 (2004–2006), 31–58; and John Wei , A Reconsideration of St. Gall, Stiftsbibliothek 673 (Sg) in Light of the Sources of Distinctions 5–7 of De Poenitentia, in: BMCL 27 (2007), 141–180.

17) The first reference in the St. Gall manuscript to the Letter to Timothy is, e.g., found only in D.35, d.a.c.1: “Nunc secundum apostolica traditione [ex descriptione corr.] videamus qualis sit ordinandus, set sobrius utique non vinolentus ordinari debet.”

18) Les ley Smi th , The Glossa ordinaria: The Making of a Medieval Bible Com-mentary (= Commentaria 3), Leiden 2009.

19) See, e.g., Cologne, Erzbischöfliche Diözesan- und Dombibliothek 25, fo. 95a v, available online, URL: <http://www.ceec.uni-koeln.de/>.

20) Ti tus Lenher r, Die ‚Glossa ordinaria‘ zur Bibel als Quelle von Gratians Dekret: Ein (neuer) Anfang, in: BMCL 24 (2000–2001), 97–129.

2. KorreKtur

KA03_Winroth_Gratian.indd 110 07.04.2013 20:09:39

The Life and Death of Gratian 111

I have delved quite deeply into Gratian’s use of the Bible and of the Glossa to the Bible, because this serves to illustrate who Gratian was and how thoroughly his thought was steeped in his reading of the Bible, even at his most “lawyerly.” Lenherr concluded that Gratian used an early form of the Glossa that had been produced by Anselm of Laon himself and by his closest students, during the first two or three decades of the twelfth century. They worked in Laon and probably in Paris, so the Glossa is yet another text from Northern France that Gratian used. Other such texts are the Panormia and the Collectio Tripartita, as well as the treatise on heresies by Alger of Liège21). Gratian not only used these works; we also find that they are embedded at the core of Gratian’s organization. Causa 24, for example, is organized around a few canons from the Panormia, which inspired the three questions that Gra-tian asked in the introductory case statement22). Alger of Liège gave Gratian not only most of the sources he used in the first question in the first Causa, but he also seems to have inspired Gratian to organize most of his work in causae and questiones23). The glossed Bible gave, as we have just seen, the framework for the first part of the Decretum.

French sources were, in other words, centrally important to Gratian. What does that tell us about Gratian’s biography? Should we look upon him as an Italian who worked in a French intellectual context, and perhaps someone who had studied in France? Gratian’s dependence on French material has, however, to be seen within context. First, Gratian also used much Italian ma-terial, such as the canonical collections of Bishop Anselm of Lucca and Cardi-nal Gregory of St. Grisogono24). Those Italian sources were just as important as French sources for the structure of the Decretum. A text in Anselm’s collec-tion provided, for example, the questions and thus the structure of C. 325). In addition, none of his French sources were new when he worked in the 1130s, and they could certainly have made it to Italy by then. Indeed, Italian manu-

21) Winro th , Making (n. 5), 15–17.22) Ti tus Lenher r, Die Exkommunikations- und Depositionsgewalt der Häretiker

bei Gratian und den Dekretisten bis zur Glossa ordinaria des Johannes Teutonicus (= Münchener theologische Studien, III: Kanonistische Abteilung 42), St. Ottilien 1987; Winro th , Making (n. 5).

23) Rober t Kre tzschmar, Alger von Lüttichs Traktat „De misericordia et iusti-tia“: Ein kanonistischer Konkordanzversuch aus der Zeit des Investiturstreits: Un-tersuchungen und Edition (= Quellen und Forschungen zum Recht im Mittelalter 2) Sigmaringen 1985.

24) Winro th , Making (n. 5), 15–16.25) John Di l lon , Case Statements (themata) and the Composition of Gratian’s

Cases, in: ZRG KA 92 (2006), 306–339.

2. KorreKtur

KA03_Winroth_Gratian.indd 111 07.04.2013 20:09:39

Anders Winroth112

scripts are known for at least some of Gratian’s sources, so there is no need to suppose that Gratian must have gone to France to collect the sources of his work. They were surely all available in Italy in his time26). That conclusion is brought out in greater relief by John Wei’s research on Gratian’s theologi-cal sources. It has long been known that Gratian in his theological passages parallels French theological writings from the early twelfth century, largely theologians influenced by Anselm of Laon, including Peter Abelard and the theologians of the house of St. Victor in Paris27). Unlike earlier scholars, Wei

26) Gratian’s library (unlike Pseudo-Isidor’s) has not been preserved, so it is strictly speaking impossible to prove which works he had access to in Italy. For each of the French works that he used, however, its manuscript transmission strongly suggests that it was available in Italy at some point in the twelfth century, so there is no a priori reason to assume that Gratian could only have found those works north of the Alps. Excerpts from Alger’s work are found in Parma, Biblioteca Palatina, Fondo Parmese 976, which is an Italian manuscript from the end of the twelfth century that otherwise contains a copy of the collection of Anselm of Lucca, see Kre tzschmar, Alger von Lüttichs Traktat (n. 23), 164–168. Gratian sometimes shares readings with this manuscript against the rest of Alger’s manuscript tradition, suggesting that he drew on a complete manuscript of the same branch of the tradition that had made it to Italy by his time. The Panormia is preserved in very many manuscripts, some of which today reside in Italian libraries and/or appear to have been written in Italy in the twelfth century, see Mar t in Bre t t ’s list of manuscripts available online, URL: <http://project.knowledgeforge.net/ivo/panormia/mslist_1p4.pdf>. The Collection in Thirteen Books, which is thought to have been compiled around 1135 in or close to Bergamo, is an expanded version of the collection of Anselm of Lucca and contains many excerpts from the Panormia and also from “French” theological sentence collec-tions used by Gratian in the De penitentia, see John C. Wei , The Sentence Collec-tion ‘Deus non habet initium uel terminum’ and Its Reworking, ‘Deus itaque summe atque ineffabiliter bonus’, in: Mediaeval Studies 78 (2011), 1–118, 18. Those works thus appear to have been available in Northern Italy at the approximate time of Gra-tian. One of the Collectio Tripartita manuscripts, Berlin, Staatsbibliothek Hamilton 345, was probably written in Italy at the middle of the twelfth century, see Mar t in Bre t t ’s listing of manuscripts, URL: <http://project.knowledgeforge.net/ivo/tripar-tita/trip_a_pref_1p4.pdf>, and Helmut Boese , Die lateinischen Handschriften der Sammlung Hamilton zu Berlin, Wiesbaden 1966, 166–167. This manuscript was at least at the end of the fifteenth century in Rome. Additionally, Pe ter Landau has argued that the Collection in Seven Books (Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana lat. 1346), compiled in central Italy around 1120, used the Tripartita A, see Pe ter Landau , Die Quellen der mittelitalienischen Kanonessammlung in sieben Büchern, in: Ritual, Text and Law: Studies in Medieval Canon Law Presented to Roger E. Reynolds, Kath leen G. Cushing/Richard F. Gyug, edd., Aldershot/U.K. 2004, 255–268. I thank Dr. Martin Brett and Dr. John Wei for their kind help with this note.

27) S tephan Kut tner, Zur Frage der theologischen Vorlagen Gratians, in: ZRG KA 23 (1934), 243–268, repr. in: S tephan Kut tner, Gratian and the Schools of Law,

2. KorreKtur

KA03_Winroth_Gratian.indd 112 07.04.2013 20:09:39

The Life and Death of Gratian 113

was able to differentiate among all these theologians. He concluded that Gra-tian shows the closest affinities with a few theological tracts and sentence collections which, while drawing on French theology, in fact derived from an Italian theological milieu28).

In sum, there is nothing in the text of the Decretum that compels us to con-clude that Gratian must have left Italy in order to be able to complete it. This should be contrasted with claims by twelfth-century writers that Gratian came to France. Foremost among those is Stephen of Rouen’s long poem known as the Draco normannicus from the late twelfth century, which claims that Gratian was in the entourage of Pope Innocent II at the council of Rheims in 113129). A chronicle written in the 1190s in the House of St. Victor in Paris fur-ther claims that Gratian was a fellow student of Pope Alexander III, which has led Giuseppe Mazzanti to conclude that Gratian must have studied theology at St. Victor30). These are the kind of sources for which we do well resorting to classical historical methodology. By those standards, they must be consid-ered narratives, which means that we cannot trust what they say, unless there is independent confirmation from other sources. There is none. They simply show what a writer in the late twelfth century thought he knew, or wished he knew about Gratian. To base one’s history on such sources is to build on sand.

In fact, it is remarkable how much writers in the late twelfth century and later thought they knew about Gratian, and how different their opinions were. A Parisian law professor thought Gratian was a monk, another that he was a bishop; a Flemish monk thought he was a cardinal, and so forth31). It is tempt-ing to simply say that it is all true, since monks who have become bishops and then cardinals are not unheard of, but that would be returning to the histori-

1140–1234 (= Collected studies CS, 185), London 1983, no. III; Anders Winro th , ‘Neither Slave nor Free’: Theology and Law in Gratian’s Thoughts on the Definition of Marriage and Unfree Persons, in: Medieval Church Law and the Origins of the Western Legal Tradition: A Tribute to Kenneth Pennington, Wolfgang P. Mül le r /Mary E. Sommar, edd., Washington/D.C. 2006, 97–109.

28) Wei , Sentence Collection ‘Deus non habet’ (n. 26); John C. Wei , Law and Religion in Gratian’s Decretum, PhD dissertation Yale University 2008.

29) Draco Normannicus 1.33, see Ét ienne de Rouen, Le dragon normand et autres poèmes, Henr i Omont , ed. (= Société de l’histoire de Normandie, Publica-tions 1), Rouen 1884, 62; and Richard Howle t t , ed., Chronicles of the Reigns of Stephen, Henry II, and Richard I (= Rerum britannicarum medii avi scriptores [Rolls series]), London 1884–1889, 2.630.

30) Giuseppe Mazzant i , Graziano e Rolando Bandinelli, in: Studi di storia del diritto 2 (1999), 79–103.

31) Noonan, Gratian Slept Here (n. 1), 151–153.

2. KorreKtur

KA03_Winroth_Gratian.indd 113 07.04.2013 20:09:39

Anders Winroth114

cal methods of a much less critical time than our own. Such an approach is fundamentally flawed32).

A better approach is to investigate whether any of these opinions have in-dependent support, and I hope to be able to show that there is independent support for the claim that Gratian was a bishop. There is no such support for other claims, not even for the idea that Gratian was a monk. This was first claimed as early as in the 1170s, by the anonymous Parisian law teacher who wrote the Summa Parisiensis33). That his claim is early makes it more likely to be correct, but the claim is still, in a methodological sense, a narrative, so it requires independent support if we are going to be believe it. Scholars have sought such support in Gratian’s supposed pro-monastic bias, but this is in fact not independent support.

The claim that Gratian favored monks was first made in the Summa Par-isiensis. Modern scholars have often restated it, but without themselves in-vestigating the claim or substantiating it further than what the Summa does. As I read the Decretum, I see no particular bias in favor of monks; Gratian of course favored the church and churchmen in general, and he allowed monks to be plaintiffs in court against previous canonical tradition, but that is the kind of liberty Gratian often allows himself. The author of the Summa Par-isiensis may simply have wanted to argue against Gratian’s conclusions, and therefore claimed that he was a monk so he could say that he was biased. Thus, I see no reason to trust this claim about Gratian’s monkishness. It is a claim in a single narrative source without any independent confirmation, so it must be set aside34).

So what can we know with certainty about Gratian? First, we must, I think, register surprise that those who were closest to Gratian seem very uninter-ested in, or at least uninformed about who he was. This starts with the man himself. In composing his Decretum, Gratian did not, unlike most of his pre-decessors and successors, write a preface, which might have provided clues to his biography35). His closest successors, Paucapalea, Rolandus, Rufinus, and Stephen of Tournai wrote prefaces to their commentaries on the Decretum,

32) Bernheim, Lehrbuch (n. 3), 541.33) Terence P. McLaughl in , ed., The Summa Parisiensis on the Decretum of

Gratiani, Toronto 1952, XVII, 115, and 181. Pe ter Landau argued at the XIVth International Congress of Medieval Canon Law in Toronto, 2012, that the Summa Parisiensis was written in Sens.

34) See also Noonan, Gratian Slept Here (n. 1), 152, n. 130.35) Rober t Somervi l le /Bruce C. Bras ington , Prefaces to Canon Law books

in Latin Christianity: Selected Translations 500–1245, New Haven 1998, 172.

2. KorreKtur

KA03_Winroth_Gratian.indd 114 07.04.2013 20:09:39

The Life and Death of Gratian 115

but they did not say anything personal about Gratian; remarkably, Paucapalea did not even mention his name36). By not providing such information, they disobeyed the conventions of writing such commentaries; a preface should account for the who – when – what of the composition they commented on37). We must conclude that they simply did not know anything about Gratian that they could tell their readers.

This is not surprising considering that the oldest manuscripts of the Decre-tum actually present the work as anonymous. The monks at Admont knew the name of Gratian when they produced their codex 23 in or close to the 1160s or 1170s, but most manuscripts of equal or greater age, of both recensions, are anonymous38). At the middle of the twelfth century, the Decretum was very famous, but Gratian was unknown.

It was this vacuum that law teachers attempted to fill in the second half of the twelfth century. The conventions of the commentary tradition were to say something about the author one was interpreting. So law teachers started to fill in the lacuna in the tradition with whatever they thought sounded plausi-ble. Perhaps some of them knew the truth, but until we can find independent confirmation of their claims, we do not know who knew the truth and who was making things up, for the greater entertainment and enlightenment of their students. It was the French law teachers and not those in Bologna who first began to say things about Gratian’s person, perhaps because the con-vention of giving biographical information about the author was stronger in France than in Italy.

One Parisian law teacher told his students that Gratian was a bishop. This opinion was recorded in an introductory gloss to the Decretum, in other words exactly the place where custom required a teacher to say something about the author he commented on. The gloss appears in eight manuscripts, none of which can be more exactly dated than to the second half of the twelfth cen-tury. In one of the manuscripts, however, the gloss talks about the Decretum as consisting of two parts, not three. Perhaps this means that this glossator wrote

36) Johann Fr iedr ich von Schul te , Die Summa des Paucapalea über das Decretum Gratiani, Giessen 1890; Somervi l le /Bras ington , Prefaces (n. 35), 180–201. Paucapalea: “the Master producing this work,” to which the translators ap-propriately added footnote 84: “I.e., Gratian.”

37) Edwin A. Quain , The Medieval Accessus ad Auctores, in: Traditio 3 (1945), 215–264.

38) Winro th , Making (n. 5), 176–177; Car los Lar ra inzar, Notas sobre las introducciones In prima parte agitur y Hoc opus inscribitur, in: Medieval Church Law and the Origins of the Western Legal Tradition: A tribute to Kenneth Pennington (n. 27), 134–153, 146.

2. KorreKtur

KA03_Winroth_Gratian.indd 115 07.04.2013 20:09:39

Anders Winroth116

before the second recension with its three parts circulated, in which case it would be very early testimony, say from the 1140s, more or less contemporary with Gratian39). This implies a presumption that the gloss might have gotten it right, but we still need independent confirmation to accept the statement.

The idea that Gratian was a bishop gets support of a sort from Robert of Torigni, who was abbot of the famous monastery of Mont Saint-Michel in Normandy. In around 1180, he claimed in a chronicle that master Gratian had been bishop of Chiusi40). In other words, we have two narratives that claim that Gratian was bishop, but unfortunately, we cannot say that these narratives are independent of each other. Robert had studied in Paris and was surely fa-miliar with local traditions there. He may have been inspired by the gloss, at one or several removes, when he claimed that Gratian was a bishop. Robert and the gloss are not demonstrably independent sources, and thus they cannot be taken to support each other. We are back where we began.

In this article, I would like to demonstrate that there exists a witness inde-pendent of Robert of Torigni and the old gloss that claims that a man called Gratian was bishop of Chiusi. This is a notice in the necrology of the cathe-dral of Siena, a source which has been long known and available in print since 1931, but which has not been correctly understood because of a sloppy scholarly error at the middle of the nineteenth century. The necrology states that “Bishop Gratian of Chiusi” died on the fourth of the Ides of August, that is, the tenth of August. It does not give the year for his death, but this is only to be expected in a necrology; such works are organized according to the ec-clesiastical year, for the purpose of recording which dead persons should be remembered in the liturgy on which date. When praying for the soul of Bish-op Gratian, as the cathedral chapter in Siena evidently did, it was irrelevant which year he died, but it was important to pray on the right day.

So who was this Gratian, who is remembered in the necrology of Siena? The obvious reference work to check for his identity is the Series episcoporum of the industrious German Benedictine Pius Bonifacius Gams41). The

39) Rudol f Weigand, Frühe Kanonisten und ihre Karriere in der Kirche, in: ZRG KA 76 (1990), 135–155, repr. in: Rudol f Weigand, Glossatoren des Dekrets Gra-tians (= Bibliotheca eruditorum 18), Goldbach 1997, 403*–423*.

40) Howle t t , Chronicles (n. 29), 4.118: „Gratianus, episcopus Clusinus, coadunavit decreta valde utilia ex decretis, canonibus, doctoribus, legibus Romanis, sufficientia ad omnes ecclesiasticas causas decidendas, quæ frequentantur in curia Romana et in aliis curiis ecclesiasticis.“

41) P ius Boni fa t ius Gams, Series episcoporum ecclesiae catholicae, Regens-burg 1873, 753. See also Conradus Eubel , Hierarchia catholica medii aevi, 2 ed. Münster 1913, 195.

2. KorreKtur

KA03_Winroth_Gratian.indd 116 07.04.2013 20:09:39

The Life and Death of Gratian 117

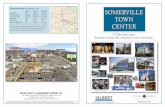

Siena, Biblioteca comunale degli Intronati F I 2, fo. 5v. The entry for Gratian is on the fifteenth date (“iiii. Id.”) from above.

2. KorreKtur

KA03_Winroth_Gratian.indd 117 07.04.2013 20:09:40

Anders Winroth118

work contains more than a thousand pages and tens of thousands of names, all the bishops of the Catholic Church from the beginning to the days of Gams.

When looking up Chiusi in Gams, one is disappointed. There is no Gratian listed among the twelfth-century bishops, only a Gratian who died on the tenth of August, 1245, just about a century after the canonist Gratian was alive. The information is exact, and thus seems to be based on a good source, so it is easy to be satisfied that Bishop Gratian of Chiusi lived in the thirteenth century and cannot have been identical to the canonist. Gams is, however, wrong when he claims that Bishop Gratian died in 1245.

When he worked out his lists of bishops, Gams did not conduct original research in the sources. He compiled such episcopal lists that already existed in a wide range of earlier works, and he never gave detailed source references. For Chiusi, he used two works in particular: Ferdinando Ughelli, Italia sacra, in its second edition by Nicolò Cole t i (otherwise known as a predecessor of Giovanni Domenico Mansi as editor of the councils), and the seventeenth volume of the Venetian priest Giuseppe Cappelletti’s great work ‘Le chiese d’Italia’ from the middle of the nineteenth century42).

Ughelli did not know of any Bishop Gratian of Chiusi at all. As bishop of Chiusi in the 1240s, he listed a Benedictus. Cappelletti, however, had con-ducted substantial research in the archives and libraries of Italy, and he knew that the necrology of Siena lists a Bishop Gratian of Chiusi. He reproduced the wording of the necrology thus: “X Augusti MCCXLV. Obiit Anselmus Diaco-nus et Canonicus S. Martini Lucensis et Gratianus Clusinus Episcopus” (“On the 10 of August, 1245, died the deacon Anselm, who was canon at St. Martin’s in Lucca, and Bishop Gratian of Chiusi”)43). On this basis, and since Ughelli did not give any detailed information at all about Bishop Benedictus, Cappel-letti deleted Benedictus from the list of Chiusi bishops, and instead he added Bishop Gratian, dead in 1245. When Gams came to Chiusi in his great work, he simply reproduced what Cappelletti had said without pursuing any inde-pendent research. Thus a Bishop Gratian who died in 1245 entered this central reference tool that has still not been replaced for the period before 1198.

Unfortunately, Cappelletti had made a fatal and really rather stupid mis-take when he claimed that Bishop Gratian died in 1245. He must have made poor notes when looking at the Siena necrology, if indeed he ever looked at

42) Ferd inando Ughel l i /Nicolò Cole t i , Italia sacra sive de episcopis Italiæ et insularum adjacentium rebusque ab iis præclare gestis deducta serie ad nostram usque ætatem, 2 ed. Venice 1717–1722; Giuseppe Cappel le t t i , Le chiese d’Italia dalla loro origine sino ai nostri giorni, Venice 1844–1870.

43) Cappel le t t i , Chiese (n. 42), 17.592.

2. KorreKtur

KA03_Winroth_Gratian.indd 118 07.04.2013 20:09:40

The Life and Death of Gratian 119

it himself. The year 1245 does not, in the manu-script, appear in the entry about Subdeacon Anselm and Bishop Gratian; it ap-pears in the previous entry, which states that the Can-on Ugerius of Siena died on 7 August, 124544). The Bishop Gratian who died in 1245 must be removed from the list of Chiusi’s bishops, while on the oth-er hand poor Bishop Be-nedictus should probably be reinstated on the basis of Ughelli’s research45).

But the Siena necrol-ogy still proves that a man called Gratian was bishop of Chiusi at some point. The question now is at what point? Could this be our Master Gratian? One does not need to have much training in paleo-graphy to discern that the notice about Gratian is noticeably older than the

44) “VII. Idus. Obit dominus Vgerius Senensis canonicus A.D. m.cc.xlv. qui fuit plebanus de Sornano.”

45) This is, however, a thorny issue, since Ughelli does not give any source for his notice about Bishop Be-nedictus, nor any more de-tailed information that allows us to trust his claim.Si

ena,

Bib

liote

ca c

omun

ale

degl

i Int

rona

ti F

I 2, f

o. 5

v, D

etai

l. Th

e to

p lin

e in

clud

es th

e no

tice

abou

t can

on U

geriu

s, w

ho d

ied

in 1

245,

an

d th

e bo

ttom

line

end

s with

“et

g(r

a)tia

n(us

) clu

sin(

us) e

p(is

copu

)s.

2. KorreKtur

KA03_Winroth_Gratian.indd 119 07.04.2013 20:09:40

Anders Winroth120

1245 entry for Ugerius. This latter entry is written in a hand that is distinctly Gothic, while Gratian’s death is recorded in a late Carolingian minuscule (or early Praegothica, to use Albert Derolez’s terminology) that would hardly have been used in Italy much after the year 1200, when Gothic hand-writing had become dominant46). This observation was first made by the Chiusi law-yer and Gratian enthusiast Francesco Reali in his book “Graziano da Chiusi”, published by the Centro Studi “Graziano da Chiusi,” of which he is the presi-dent47). I remain very grateful to Mr. Reali not only for kindly sending me his book but also for helping me organize my visit to Siena and Chiusi in the late summer of 201148) .

Reali’s observations may be substantiated through close study of the hands of the manuscript. The hand of the Gratian notice has kept several Carolingian features, such as the sloping shaft of a and the open lower bow of g , while also accepting several Pregothic features, such as the slight angularity of the letters c and n , the tironian sign for e t , and the sloping last straight stroke of e . All of this firmly places the hand in the twelfth century, and earlier rather than later49).

The notice about Bishop Gratian may be even more exactly dated through examining the Siena necrology manuscript, which today is preserved in the Biblioteca comunale degli Intronati in Siena. The necrology is written on a quire of eight large sheets, measuring about 55 by 27 centimeters. This quire is bound together with a manuscript containing Augustine’s In Iohannis evangelium tractatus, plus a couple of shorter works. I doubt that the necrol-ogy originally was placed in this context – it would more usefully have been paired with liturgical texts than with theological works. It was probably bound into this volume because it is written on leaves of about the same size. The parchment on which the necrology has been written is of rather poor quality, and it is quite worn50).

46) Alber t Dero lez , The Palaeography of Gothic Manuscript Books from the Twelfth to the Early Sixteenth Century, (= Cambridge studies in palaeography and codicology 9), Cambridge 2003.

47) Francesco Real i , ed., Graziano da Chiusi e la sua opera: Alle origini del di-ritto comune europeo (= Pubblicazioni del Centro studi magister Gratianus 1), Chiusi 2009.

48) I remain deeply grateful to Onedo Meacci, Marco Fè, and Niccolò Chiuppesi for their exceptional hospitality and for guiding me through the cathedral, its museum, the catacombs, and other historical monuments of Chiusi. I also wish to thank Chiusi’s sindaco Stefano Scaramelli and assessore Chiara Lanari for their kind welcome.

49) Dero lez , Palaeography (n. 46), 58–66.50) I thank the staff of the Biblioteca comunale degli Intronati in Siena for allowing

2. KorreKtur

KA03_Winroth_Gratian.indd 120 07.04.2013 20:09:40

The Life and Death of Gratian 121

Many different scribes have written on the sixteen pages of the quire, rang-ing from the twelfth-century elegant late Carolingian of the original scribe to a couple of notices written in Humanistic cursive in the fifteenth century. The necrology was edited in 1931 by the Sienese historian and archivist Alessan-dro Lisini. This edition cannot be said to live up even to the demands of its time. Lisini roughly differentiated among hands of different centuries, but not among individual hands. He no more than suggested the layout on the page, and the commentary is inadequate, focusing mostly on well-known events in the history of Siena, while making few attempts at identifying the persons mentioned51). A new edition is very much desired, and should preferably be accompanied by a facsimile of the necrology.

The necrology itself tells us when it was created. Its notice about the death of the Sienese Bishop Gualfredus states that his successor Rainerius, who took up office in 1129, “ordered this quire to be made”52). The original scribe first wrote out the Sunday letters and the dates in a column on the left side of the page, in addition to the names of the appropriate saints for each date on the right side of the page. “[Festum] Laurentii martyris” is, of course, men-tioned under 10 August. The original scribe then added the names of about thirty-five persons, each under the date of their death. In no case did he also provide a year for their death. The names include a single pope – Alexander II – as well as Bishop Gualfredus of Siena. Before he became pope in 1061, Alexander was Bishop Anselm (I) of Lucca. The original set of names also included at least three canons of the chapter at Lucca. The reason for all this Lucca material, which may appear out of place in a necrology from Siena, must be the fact that Bishop Rainerius in 1131 invited canons from Lucca to

me to see the manuscript and for sharing with me their inhouse description of it. I also thank the library for permission to reproduce fo. 5v in this article.

51) Alessandro Lis in i , ed., Kalendarium ecclesiae metropolitanae Senensis (= Rerum Italicarum scriptores: Raccolta degli storici Italiani: Nuova edizione 15:6: Chro nache Senesi 1), Bologna 1931, 3–36. An obvious reference tool such as Gams, Series episcoporum (n. 41), is not, e.g., consistently cited for bishops found in the ne-crology. See similar criticism of the edition in Paolo Cammarosano, Tradizione documentaria e storia cittadina: Introduzione al “Caleffo Vecchio” del Comune di Siena, Siena 1988, 20, n. 42.

52) Siena, Biblioteca comunale degli Intronati F I 2, fo. 5r: “[Kal. Aug.] viiii Obiit Gualfredus episcopus anno Domini MCXXVII, et in secundo anno sequenti Rainerius episcopus, qui hunc quaternum fieri fecit, Senas venit et eodem anno a Senensibus captus est archiepiscopus Pisanus.” Lis in i ’s ed. (n. 51), p. 21–22, incorrectly reads “quinternum” instead of “quaternum.” Böhmer (see n. 54) has the correct reading, as Lisini notes.

2. KorreKtur

KA03_Winroth_Gratian.indd 121 07.04.2013 20:09:40

Anders Winroth122

serve him in Siena. Apparently, they brought with them the model of the Siena necrology. Thus, we may conclude that the necrology was first drawn up in Siena in 1131 or soon thereafter, as already Lisini pointed out.

It is possible to push the terminus post quem even later. The original scribe also wrote the notice about Bishop Crescentius of Volterra, who died in Au-gust of 1136, if we can trust what Gams and Cappelletti say53). If also this notice, as I believe, was included when the manuscript was first drawn up, that cannot have happened before 1136.

A second hand, hand B, added about twelve further death notices in a some-what similar script, which if anything appears more old-fashioned than hand A, since it employs longer ascendants in comparison with the height of the letter body. Neither hand A nor hand B ever included the year of death of the persons they wanted remembered. Only later hands, which wrote in the thir-teenth century and later, added years to a few of the old notices, for example, for Bishops Gualfredus and Rainerius of Siena. (Lisini’s edition does not note such changes of hands.) Overall, in the thirteenth century, the necrology started to be used as a depository of historical information, rather than as a liturgical document. This was when a series of annalistic notices were added, under their appropriate dates54). A series of hands added information about war events, the death of popes and emperors.

53) Siena, fo. 5v, ed. L is in i (n. 51), 24. According to Gams, Series episcoporum (n. 41, 763, Bishop Crescentius died on 13 August 1136 after having become bishop of Volterra in 1134. This latter year must be a misprint since his source, Cappel le t t i , Chiese (n. 42), 18.231, stated that Crescentius became bishop already in 1132, which probably is correct since a letter of September 1133 mentions Crescentius as bishop, see Fedor Schneider, Regestum Volaterranum: Regesten der Urkunden von Volt-erra (778–1303) (= Regesta chartarum Italiae 1) Rome 1907, 57, n. 163, and Paul F. Kehr, Italia pontificia 3: Etruria, Berlin 1908, 284, Episc. Volterra n. 17. The Siena necrology gives his death date as 17 August. Cappelletti, who like Gams states that Crescentius died on 13 August, 1136, gives as his source “il regesto Caleffo della fab-brica di Siena.” This probably refers to the Siena necrology (rather than the “Caleffo vecchio” of the Siena commune), but it is hard to fathom on what basis Cappelletti claimed that Crescentius died in 1136, since that date is not in the necrology. Cappel-letti had a reputation for being cavalier with his sources, and the evidence uncovered in this article supports this. Crescentius is at any rate mentioned as alive in a docu-ment of February, 1135, so Cappelletti’s year cannot be very far off, see Schneider, Regestum Volaterranum 58, n. 164. I thank Professor Mario Ascheri, Siena, a co-editor of the “Caleffo vecchio,” for discussing Cappelletti’s source with me.

54) A selection of notices from the necrology, including the annalistic notices, were reprinted, rearranged in chronological order, by Johann Fr iedr ich Böhmer as: “Annales Senenses” in: Monumenta Germaniae Historica: Scriptores 19, Hannover

2. KorreKtur

KA03_Winroth_Gratian.indd 122 07.04.2013 20:09:40

The Life and Death of Gratian 123

But let us return to the twelfth-century notice remembering the death of Bishop Gratian of Chiusi. It was hand B which added the notice about Gratian under the entry for the tenth of August, where hand A had already included the notice about the death of the canon and subdeacon Anselm of St. Martin’s in Lucca, who according to documentary evidence was still alive in 113155). Hand A wrote at some point after 1136, while hand B wrote after hand A, but probably not very long after. Such is the terminus post quem for Gratian’s death.

For the terminus ante quem, we may look to the death notice of Bishop Rainerius. He lived as bishop of Siena for a long time from his appointment in 1129 until he died in 1170. His death was recorded in the necrology, suppos-edly soon after it happened, by what I have called hand C. This hand writes in a script with clear Gothic (rather than pregothic) traits, including broken and articulated lines. The difference between this hand and hands A and B is clear and very great, so there must be some distance in time between them. Hands A and B must predate 1170 and hand C by more than a few years.

The conclusion of this paleographical examination of the Siena necrology is that the notice about the death of Bishop Gratian of Chiusi must have been entered at some point between, roughly and conservatively, 1136 and 1160. In other words, the Sienna necrology shows that Bishop Gratian of Chiusi lived at about the same time as the canonist Gratian, whose Decretum, as extant, could not have been written before 113956).

So how do we evaluate the evidence that I have just presented? For starters, the necrology of Sienna is a relic of the liturgical celebrations in Siena Ca-thedral. We may thus take it as proven beyond doubt that the twelfth-century chapter at Siena remembered liturgically a Bishop Gratian of Chiusi on 10 August. In general, we may count on such liturgical celebrations to reflect

1866, 225–235. For earlier editions, see: Repertorium fontium historiae Medii Aevi primum ab Augus to Pot thas t digestum, nunc cura collegii historicorum e pluribus nationibus emendatum et auctum, Rome 1962–2007, 8.164.

55) Subdeacon Anselm (or “Anselminus”) of Lucca is mentioned as living in docu-ments from 1125 and 1131, see P ie t ro Guid i /Ores te Parent i , eds., Regesto del Capitolo di Lucca, vol. 1 (= Regesta chartarum Italiae, 6) Rome 1910, 354–355 and 380, n. 821, 822, and 878. See also Raffae le Savigni , Episcopato e società a citta-dina a Lucca da Anselmo II (1086) a Roberto (1255) (= Studi e testi 43), Lucca 1996, 415. Anselm does not appear in the necrology of the chapter of Lucca, as preserved in Lucca, Biblioteca capitolare 618, see Savigni , Episcopato e società, 475–490. I thank Professor Andreas Meyer, Marburg, for providing these references.

56) The date of the first recension of the Decretum is debated, see Winro th , Recent Work (n. 16), 5–6.

2. KorreKtur

KA03_Winroth_Gratian.indd 123 07.04.2013 20:09:40

Anders Winroth124

correct information about the deaths of people remembered. In any case, the necrology and Robert of Torigni independently of each other claim that a Gra-tian was bishop of Chiusi close to the middle of the twelfth century, so that must be considered a securely established fact. Was that Bishop Gratian also identical to Master Gratian? Robert of Torigni claimed that he was, but we have no independent confirmation of this claim, which in a technical sense is a narrative. The name Gratian is not unique; several, but not many, twelfth-century Gratians in different positions in Italian society are known57). The name is unusual enough, however, that we may conclude that it is likely that the canonist Gratian died as bishop of Chiusi.

Thus we are able to fill in a new, important detail in the otherwise poorly known biography of the father of the scientific study of canon law. We used to know only two things for certain about Gratian: that he wrote at least some version of the Decretum, and that he was in Venice in 1143 together with two other Bologna jurists58). Now we have a third very likely fact: that Gratian died on 10 August as bishop of Chiusi.

Gratian thus joins the large group of school men, who were teaching to gain merits for ecclesiastical advancement. To be a teacher, even a famous and pio-neering teacher like Gratian, was not well paid work, and most teachers and scholars were striving for promotion into the ecclesiastical hierarchy. Among canonists, we are familiar with the careers of Omnibene becoming bishop of Verona, Huguccio becoming bishop of Ferrara, Stephen becoming first abbot of St. Geneviève and then bishop of Tournai, and Johannes Teutonicus, who seems to have been content with the provostship of Halberstadt59). Among

57) I am grateful to Dr. Gundula Grebner, Heidelberg, for discussing with me the appearance of the name Gratian in Italian sources, and especially those of Bologna, which she studied closely and prosopographically for her dissertation Gundula Grebner, ‘omnis racio vel contempcio bona fidei, que vite homines aguntur’: No-tarielle Kultur und Wechsel der Generationen in der Entstehung von Kommune und ‘Studium’ in Bologna (1050–1150), PhD thesis, Universität Frankfurt am Main 1999.

58) That the Gratian mentioned in this document is identical with the canonist is argued by Gundula Grebner, Lay Patronate in Bologna in the First Half of the 12th Century: Regular Canons, Notaries, and the Decretum, in: Europa und seine Regionen: 2000 Jahre Rechtsgeschichte, Andreas Bauer /Kar l H.L. Welker, edd., Vienna 2007, 107–122.

59) Kenneth Pennington , Medieval and Early-Modern Jurists: A Bio-Biblio-graphical Listing, online available, URL: <http://faculty.cua.edu/Pennington/1140a-z.htm.> – Many other examples of canonists who became bishops or prelates may be added to this list, see, e.g., several persons mentioned in Pe ter Landau , Die Köl-ner Kanonistik des 12. Jahrhunderts: Ein Höhepunkt der europäischen Rechtswissen-schaft, Badenweiler 2008.

2. KorreKtur

KA03_Winroth_Gratian.indd 124 07.04.2013 20:09:40

The Life and Death of Gratian 125

theologians, we might think of Peter Lombard, who taught his famous course of systematic theology as preserved in the Sentences only twice before he became bishop of Paris in 1159, although he had the misfortune of dying within only a year of achieving his career goal60).

Like Peter Lombard, Gratian worked hard to teach, and like the Lombard, he succeeded in gaining a bishopric, if my conclusions about the Gratian in the Siena necrology are correct. Such positions, with their typically large endowments, were at the center of every young man’s career dreams. The question now is exactly when Gratian was bishop of Chiusi. He was not yet a bishop when the cardinal judged a legal case in Venice in 1143, since the conventions of letter composition (dictamen) would have required that such an ecclesiastical dignity be recorded in the document. Unfortunately, the bishops of Chiusi in the twelfth century are poorly known. For the next twenty years after 1143, we only know that a Martinus was bishop of Chiusi on 5 May, 1146. He was succeeded (although not necessarily directly) by an Ubertus, whose tenure is known only to have followed Martinus and to have preceded 115961).

There are, in other words, plenty of holes in the list of Chiusi bishops where Gratian might fit in. He might have become bishop soon after his appearance in Venice in 1143, dying on 10 August in 1144 or 1145. Or he could have suc-ceeded Martinus or Ubertus. It is impossible to know exactly when Gratian was bishop. I would in any case like to suggest, as a working hypothesis, that Gra-tian stopped teaching soon after his appearance in Venice in 1143 to govern the bishopric of Chiusi, but that he, like Peter Lombard, had the misfortune of dy-ing soon after reaching the episcopacy, on the tenth of August in either 1144 or 1145, being succeeded by Martinus. This scenario would fit well with what we may learn about Gratian from the Decretum itself. He would have taught the first recension in Bologna at least during the first years of the 1140s. Perhaps he only taught the Decretum once. Indeed, the work as it appears in the first recension looks unfinished, since it does not treat baptism, confirmation, and the consecration of churches, subjects which one would think would have in-terested the practical theologian Gratian. Did he become bishop before he had finished his course the first time he taught it? There is no reason to assume, as is often done, that Gratian must necessarily have had a very long teaching ca-

60) Magistri Pe t r i Lombardi Parisiensis episcopi Sententiae in IV libris distinc-ta (= Spicilegium Bonaventurianum 4–5), 3 ed. Grottaferrata 1971–1981, 32*–35*; Marc ia L . Col i sh , Peter Lombard (= Brill’s studies in intellectual history, 41), Leiden 1994.

61) See Appendix.

2. KorreKtur

KA03_Winroth_Gratian.indd 125 07.04.2013 20:09:40

Anders Winroth126

reer. Indeed, as nobody in the schools remembered very much about him, there might be good reasons to assume that his teaching career was rather short. His great reputation rested on his work, and there is little reason to think that the Decretum must have taken very much longer to compile than the Lombard took to compose his equally complex and sophisticated Sentences , which clearly were put together during two academic years 1156–1158. The Sentences is, however, a shorter work than the Decretum and the Lombard was certainly well prepared after having produced several earlier theological works62).

Gratian abandoned teaching to take up what he and his contemporaries would have considered a real job: the bishopric of Chiusi, just like the Lom-bard abandoned his theological teaching to become bishop of Paris. The De-cretum remained for other teachers to pick up and use in their own teaching. One (or some) of them expanded the text into the second recension, after Gratian’s move to Chiusi and before 115063). Meanwhile, out of sight is out of mind; the human person Gratian fell out of most people’s memory, while his book remained at center stage in canon law.

This scenario is, of course, only hypothetical, but it has the advantage of fitting the securely known facts about Gratian’s life and work, and it would explain the disjunction in the style of the Decretum that I and others have observed between the first and the second recension. Gratian produced the first recension, while someone else produced the second after Gratian had abandoned teaching to live as bishop in Chiusi.

In Chiusi, Gratian presided over an important hilltop city, with a cathedral built in Lombard times on the site of a Roman villa with a beautiful mosaic floor, today the floor of the choir. Chiusi has never doubted that Gratian be-longs to it, and the city is fiercely proud of him. There is a local school bearing his name, and the best local gelato is to be had on Piazza Graziano. The city park displays his 1938 bust, which still carries a wound from being shot at during the Second World War, when the German army for a couple of weeks tried to hold Chiusi against Allied forces.

Gratian’s earliest episcopal predecessors were buried in a catacomb that had been forgotten by Gratian’s time and was only rediscovered accidentally when the Franciscan convent of St. Mustiola dug a well in the seventeenth century. Bishops in Gratian’s time were typically buried in their cathedrals, and the Chiusi Duomo has a crypt, which according to the old, although surely

62) Pe t r i Lombardi Sententiae (n. 60), 122*–129*.63) Paolo Nard i , Fonti canoniche in una sentenza senese del 1150, in: Life, Law

and Letters: Historical Studies in Honour of Antonio García y García, Pe ter Line-han , ed. (= Studia Gratiana, 29) Vatican City 1998, 661–670.

2. KorreKtur

KA03_Winroth_Gratian.indd 126 07.04.2013 20:09:40

The Life and Death of Gratian 127

post-medieval inscribed stone resting above it is the Sepulchrum vetuS epiS-coporum et capituli cathedraliS cluSini, “the old burial site of the bishops and chapter of the cathedral of Chiusi.” Is this ancient tomb the final resting place of the father of canon law, where he sleeps his eternal sleep? It is im-possible to know. The old episcopal palace next to the Duomo should, at any rate, have a plaque: “Gratian slept here.”

Appendix : Pre l iminary Lis t o f Bishops of Chius i in the Twel f th

Century

In preparing this article, I attempted to compile a list of twelfth-century bishops of Chiusi. What follows is based entirely on a literature survey and must be considered only a first beginning of such a list, although archival material from twelfth-century Chiusi appears to be very rare.

Petrus111664)[1118]65)1125/112666)[1139, 21 Dec.]67)Gratianusc. 1136/1160, perhaps c. 1143–c. 1145Martinus1146, 5 May68)

64) Cappel le t t i , Chiese (n. 42), 17.586, citing a medieval cartulary called “Liber delle Coppe” (“hodie in R. archivo Senensi,” according to Kehr, Italia pontificia (n. 53), 236).

65) The bishop of Chiusi, mentioned without name, together with the bishops of Arezzo and Pistoia, ordains Bishop Benedictus of Lucca on the orders of Pope Gela-sius II. The source is a necrology at Lucca, quoted by Harry Bress lau , Reise nach Italien im Herbst 1876, in: Neues Archiv 3 (1878), 77–138, 138. See also Kehr, Italia pontificia (n. 53), 391, Episc. Lucca, n. 20.

66) Kehr, Italia pontificia (n. 53), 244, Eremus S. Petri et s. Benedicti de Vivo, n. *2–3

67) The bishop of Chiusi is mentioned without name on a marble tablet in the wall of the church of San Tommaso in Parione, Rome, commemorating its consecra-tion by Pope Innocent II, see Ughel l i /Cole t i , Italia sacra (n. 42), 631. See also photo at <http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Parione_-_s_Tommaso_lapi-de_1139_1150360_.JPG.>

68) Ughel l i /Cole t i , I t a l ia sacra (n . 42) , 631, quoting a notarized copy 4 February 1250.

2. KorreKtur

KA03_Winroth_Gratian.indd 127 07.04.2013 20:09:40

Anders Winroth128

Ubertus1146/1159. After Martinus, according to privilege for the church of S. Mustiola issued 12 May 115969).Rainerus117070)1176 oct.71)Leo1179: attended the Third Lateran Council72).Theobaldus1191 dec 2773)1192 april 1974)

69) Kehr, Italia pontificia (n. 53), 235, Ecclesia s. Mustiolae, n. 4.70) Ughel l i /Cole t i , I ta l ia sacra (n . 42) , 631, citing “Liber delle Coppe.”71) Cappel le t t i , Chiese (n. 42), 17.586–587, quoting a document in “Liber delle

Coppe.”72) Gian Domenico Mans i , Sacrorum conciliorum nova et amplissima collec-

tio, Florence and Venice 1759–1798, 22.214.73) Kehr, Italia pontificia (n. 53), 234, Episc. Chiusi, n. 15.74) Kehr, Italia pontificia (n. 53), 234, Episc. Chiusi, n. 17.

2. KorreKtur

KA03_Winroth_Gratian.indd 128 07.04.2013 20:09:40