Ancient culture of Greece and Rome.library.miit.ru/methodics/2401.pdf · Ancient culture of Greece...

Transcript of Ancient culture of Greece and Rome.library.miit.ru/methodics/2401.pdf · Ancient culture of Greece...

МОСКОВСКИЙ ГОСУДАРСТВЕННЫЙ УНИВЕРСИТЕТ ПУТЕЙ СООБЩЕНИЯ (МИИТ)

Кафедра лингвистики

Л.А.ЛАШИНА

Ancient culture of Greece and Rome.

Part II. Arts.

Методические указания.

МОСКВА -2 0 0 6

№240.103-14155

Ancient culture o f Gree ce and Rorne|'06Part 11

I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I IH I I I I I I I I I I ЫЙ УНИВЕРСИТЕТ_______________ 11У1ЕИ и л л и ц ь ш ш (МИИТ)____________

Кафедра «Лингвистика»

Л.А. Лашина

Ancient culture of Greece and Rome.

Part II. Arts.

Рекомендовано редакционно-издательским советом университета в качестве методических указаний для

студентов специальности

«Перевод и переводоведение»

Москва - 2006

УДК 49Л 32

Лашина Л.А. Ancient culture of Greece and Rome. Part II.

Arts., Методические указания, часть II. - M.: МИИТ, 2006. - 56 с.Методические указания предназначены для студентов высших учебных

заведений для лингвистических специальностей, в том числе для специальности «Перевод и переводоведение».

Работа содержит ряд тематических адаптированных текстов современных английских и американских антиковедов и культурологов. В первой части дан краткий исторический очерк Древней Греции и Древнего Рима, а также статьи, посвященные мифологии, истории литературы и образования этих стран.

Вторая часть включает в себя статьи о древнегреческом и древнеримском театре, об архитектуре, скульптуре и живописи античности. Работа сопровождается кратким фонетическим словарем (RP) имен собственных по данной тематике, а также снабжена наиболее характерным для этого периода иллюстративным материалом.

© Московский государственный университет

путей сообщения (МИИТ), 2006

Contents:

Introduction...............................................................................4

1. Theatre in Greece................................................................. 5

Roman theatre........................................................................8

2. Architecture........................... 10

3. Sculpture...............................................................................17

4. Painting..................................................................................24

5. Appendix 1............................................................................ 28

6. Appendix IT ,........................................................................ 41

7. Bibliography......................................................................... 55

Introduction.

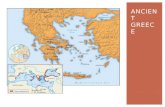

A history of Greek and Roman art is the history of one of the

richest and most inventive artistic cultures, lying at the root of the European

tradition. The most interesting is the change in the different branches of

representational art as aspects of a single historical development. The

genuinely Greek and markedly different artistic tradition as opposed to art in

the Mycenaean Bronze Age appears at about 1000 B.C. and atrophies

eventually in the 1st century B.C.. Something of its afterlife as an important

strand in the art of the Roman Empire is indicated as an epilogue of Graeko-

Roman Art.

Greek and Roman art primarily deals with the great monumental

tradition, with architecture and its development and its relation to sculpture

and painting.

The marble sculptures from temples and other sanctuary buildings

are the greatest things which remain from Greek art. However the bronze

statuary was in certain periods more favored than marbie sculpture, yet our

knowledge of it is largely through the sad medium of marble copies mass-

produced centuries later under the Roman empire. Painting too was

esteemed a great art but all our knowledge of that is still more indirect and

inadequate. The arts of certain times and places (ancient Egypt, for instance

or mediaeval Europe) are dominated by rigid traditions which the

individuality of each artists can only slightly modify: in others the tradition

is a dissolving one, perpetually recreated by powerful artistic personalities.

Such has been the character of the European art since the Renaissance, and

such it was in classical Greece. To understand the development of an art of

this kind one must know something of the artist, yet we possess scarcely one

undisputed original by one of the great names in Greek sculptures, let alone

painting.

The question of how much in the art of the Roman empire was

really the work of Greeks is much discussed, but evidence allowed of no

clear conclusion. Even the arts of the eastern and western frontiers had some

of their roots in Greece, but they had grown a long way from them. In

Greece and Asia Minor which had suffered less in the troubles of the 3rd

century A.D. than other parts of the Roman empire, the tradition of classical

and Hellenistic art was less drastically modified by external influences and

new development than in Rome and in the West. When Konstantine moved

the seat of Imperia to Byzantium in 323 A.D., the court in the new capital

inherited this tradition, and classical forms linged long in its art. It was a

new art however. Christianity was to prove a more powerful catalyst of

Hellenism than had the imperial idea, and we can pursue the fortunes of the

subsequent Greek contribution no further.

1. Theatre in Greece.

The Greek theatre was originally intended for performance at the

feast of Dionysus. From the first it consisted of two principal parts: the

circular dancing-place, orchestra, with the altar of the god in the centre; and

the place for the spectators, or the theatron proper. The theatron was in the

form of a segment of a circle, greater than a semi-circle, with the seats rising

above one another in concentric tiers. The seats were almost always cut in

the slope of a hill. When the choruses had developed into the drama, a

structure called the skene was added with a stage for dramatic

representations. It was erected on the side of the orchestra away from the

spectators and at such a height and distance as to allow of the stage being in

full view from every part of the theatre.

The first stone theatre was built at Athens, the home of the Greek

drama, and the theatres in every part of the Hellenic world were constructed

on the same general principles. The building was near the east end of the

southern slop of the Acropolis and in its construction partial use was made

of the rock against which it rested. It was not, however, completed until

between 340 and 330 B.C. when Athens was under the financial

administration of Lycurgus. The remains of this theatre have been exposed

to view since the excavation of 1862. With the spread of dramatic

representations stone theatres were built in every part of the Hellenic world;

and, shortly after the time of Alexander the Great, they were practically

universal. It has been estimated that the theatre at Athens had room for

27,500 persons. Among other large theatres may be mentioned in Greece (

in Megalopolis, Sparta, and Epidaurus), in Sicily, that of Syracuse; in Asia

Minor, those of Ephesus and Miletus. There were also large theatres in

Crete.

In the Greek theatre the normal number of the stairs was even; in

the Roman it was usually uneven. In the Athenian theatre the front row of

seats were reserved for priests and other ministers of religion, and the rest

for the officials of the State. The central seat in this row was reserved for the

priest of Dionysus. The right of occupying a reserved seat in one of the front

rows was provided for public benefactors, for the orphans of those who had

fallen in war, and for ambassadors from foreign states. The judges of the

dramatic competitions sat together. They naturally had some of the best

places assigned to them. Behind the front row were placed a number of

inferior priests and priestesses. The tickets of admission were discovered in

Attica. Women were generally present at the performance of tragedies but

from that of comedies those of the higher classes usually stayed away. In the

5th century B.C. the women sat in a separate part of the theatre at the back.

Boys were admitted, slaves probably not. The provision against sun and rain

customary in the Roman theatre was unknown to the ancient Greeks.

The orchestra was considerably below the level of the stage. The

chorus entered the orchestra by means of passages on either side of the

stage. But as a general rule, the chorus remained in the orchestra at a lower

level than the stage. The scenery was very simple. Like many other things

connected with the stage it was first introduced either by Aeschylus or by

Sophocles. The principal decoration consisted of a light and movable screen

placed in front of the wall at the back of the stage. On this screen the scene

of the play was painted. In tragedy it was usually the front of a king's palace

with three doors. In connection with the action of the play accessories, such

as altars, statues and tombs were introduced when necessary. There is no

direct evidence for a drop curtain in the Greek theatre. Machinery of various

kinds was used to imitate thunder and lightning. Casks filled with pebbles

were sent rolling down bronze surfaces for that purpose. There were also

contrivances for making persons appear or disappear in the air. In order to

make the actor's voice more audible at a distance vessels of bronze of

different tones were sometimes suspended in niches in various parts of the

auditorium. Niches of the kind have been observed in the remains of the

theatre at Aizani in Phrygia and in Crete. Theatres were frequently used for

public purposes unconnected with the drama. At Athens the custom of using

the theatre for assemblies of the people prevailed from the middle of the 3rd

century B.C.

The Roman Theatre.

In Rome where dramatic representations in the strict sense of the

term were not given until 240 B.C., a wooden stage was erected in the

Circus for each performance and taken down again. The place for the

spectators was a space surrounded by a wooden barrier within which the

public stood and looked on in a promiscuous mass. In 194 B.C. a place was

set apart for the senators nearest to the stage but without any fixed seats;

those who wanted to sit had to bring their own chairs; sometimes by order of

the Senate sitting was forbidden. In 154 B.C. an attempt was made to build a

permanent theatre with fixed seats but it had to be pulled down by order of

the Senate. In 145 B.C. on the conquest of Greece theatres provided with

seats after the Greek model were erected. They however were only of wood

and served for one representation alone. Such was the splendid theatre built

in 58 B.C. by the Aemilius Scaurus, containing, among other decorations,

3,000 bronze statues, and provided with 80,000 seats. The first stone theatre

was built by Pompey in 55 B.C., a second one by Cornelius Balbus (13

B.C.) and in the same year the one dedicated by Augustus to his nephew

Marcellus was erected and called by his name. The ruins of the third above

mentioned theatre still exist. The first of these contained 17,500, the

second-11,510, and the third-20,000 seats. Besides these there were no

other stone theatres in Rome. Wooden theatres continued to be erected

under the Empire.

The Roman theatre differed from the Greek one. It the first place,

the auditorium formed a semicircle only with the front wall of the stage

building as its diameter, while in Greece it was larger than a semicircle. A

covered colonnade ran round the highest story of the theatre, the roof of

which was of the same height as the highest part of the stage.

The auditorium contained places for spectators that were, at first,

reserved exclusively for the senators and foreign ambassadors. The most

distinguished places were the two balconies over the entrances to the

orchestra on the right and left side of the stage; in one of these the giver of the

entertainment and the emperor sat, in the other the empress and the Vestal

Virgins did. In the upper part of the auditorium were the women who sat

apart in accordance with a decree of Augustus (they had formerly sat with

the men). Even children were admitted, only slaves being excluded.

Admission was free as was the case with all entertainments intended for the

people. The tickets of admission did not indicate any particular seat but only

the block of seat and the row in which it would be found.

The stage was raised five feet above the orchestra in order that the

spectators might easily overlook every part of it. It was considerably longer

and wider than the Greek stage, as in the Roman theatre there were nearly as

many actors as parts, and the Romans were very fond of splendid stage-

processions. There were two altars on the stage, one dedicated to Liber in

remembrance of the Dionysian origin of the drama, the other to the god in

whose honour the play was held.

With regard to the scenery, which certainly cannot have been

introduced before 99 B.C., and the scene-shifting, for which elaborate

machinery of various kinds existed, the Roman stage did not essentially

differ from the Greek one, except that it had a curtain. This was lowered at

the beginning of the play instead of being drawn up as with us and it was not

raised again until the end: there was also a smaller curtain which served as a

drop-scene.

H. Architecture of the Greeks.

Of the earliest efforts of the Greeks in architecture we have

evidence in the so-called Cyclopean walls surrounding the castles of king in

the Heroic Age, at Tiryns, Argos, Mycene and elsewhere. They were of

enormous thickness, some being constructed of rude colossal blocks whose

gaps were filled up with smaller stones. The others were built of stones

more or less carefully hewn, their interstices exactly fitting into each other.

Gradually they began to show an approximation to buildings with

rectangular blocks. The oldest specimen of Greeks sculpture was the famous

Lion-gate at Mycene. Among the most striking relics of this primitive age

were the tombs (treasuries) of ancient dynasties, the most considerable of

them having been the Treasure-house of Atreus at Mycene. The interior was

originally covered with metal plates, thus agreeing with Homer’s description

of metal as favourite ornament of princely houses. An open-air building

preserved from that age is the supposed Temple of Hera on Mount Ocha, a

rectangle built of regular square blocks with walls more then a yard thick,

two small windows and a door with leaning posts and a huge lintel in the

southern sidewall. The sloping roof was of hewn flagstones resting on the

thickness of the wall and overlapping each other, but the centre was left

open. From the simple shape of a rectangular house shut in by blank walls

the Greeks gradually advanced to finer and richer forms formed especially

by the introduction of columns detached from the wall and serving to

support the roof and ceiling. Even in Homer there can be found columns in

the palaces to support the halls that surround the court-yard and the ceiling

of the banqueting-room. The construction of columns received its artistic

development first from the Dorians after their migration into the

Peloponnesus about 1000 B.C., next from the Ionic. By about 650 B.C. the

Ionic style was flourishing side by side with the Doric.

Architecture had developed her favourite forms, all other public

buildings borrowed their artistic character from the temple. About 600 B.C.,

in the Greek islands and on the coast of Asia Minor one can come across the

first architects known to us by name. It was then that Rhecus and Theodorus

of Samos built the great temple of Hera in that island while Chersiphron of

Cnosus in Crete with his son Metagenes began the temple of Artemis

(Diana) at Ephesus, one of the Seven Wonders of the World, which was not

finished till 120 years after. In Greece a vast temple to Zeus was begun at

Athens in the 6th century B.C. and two more at Delphi and Olympia, one by

the Corinthian Spintharus, the other by the Elean Libon. Here and in the

Western colonies the Doric style still predominated. Among the chief

remains of this period in addition to many ruined temples in Sicily the

Temple of Poseidon at Pastum in South Italy should be mentioned which

was one of the best preserved and most beautiful relics of antiquity. The

patriotic fervor of the Persian Wars created a general expansion of Greek

life in which Architecture and Sculpture took a part. In the whole onward

movement a central position was taken by Athens whose leading statesman,

Cimon and Pericles, lavished the great resources of the State at once in

strengthening and beautifying the city. During this period a group of

masterpieces arose that astonished our contemporaries even in their ruins,

some of them having been in the Ionic style which had then found its way

into Attica. The Doric order was represented by the Temple of Theseus, the

Propyle built by Mnesicles, the Parthenon that was a joint production of

Ictinus and Callikrates. At the same time Erechtheum was the most brilliant

creation of the Ionic order in Attica. There were many proofs of the Attic

Architecture influence on the rest of Greece, especially in the Temple of

Apollo at Basse in South-Western Arcadia built from the design of the

above-mentioned Ictinus.

The progress of the Drama to its perfection in this period (5th

century B.C.) led to a corresponding improvement in the building of

Theatres. A stone theatre was begun at Athens even before the Persian Wars

and the Odeon of Pericles served similar purposes. The highest results was

shown by the theatres at Epidaurus, a work of Policlitus, unsurpassed as the

ancients testified, by any later theatres in harmony and beauty. Another was

built at Syracuse before 420 B.C.

In the 4th century B.C., owing to the change arisen in the Greek

mind by the Peloponnesian War, in place of the pure and even tone of the

preceding period a desire for effect became more and general both in

architecture and sculpture. The sober Doric style fell into abeyance and gave

way to the Ionic one. Side by side with it a new, the Corinthian order, have

been invented by the sculptor Callimachus with its more gorgeous

decorations and became increasingly fashionable, in the first half of the 4th

century B.C. the largest and grandest temple in the Peloponnesus arose, that

of Athena at Tegea, a work of the sculptor and architect Scopas. During the

middle of the century, another of the “seven wonders”, the splendid tomb of

Mausolus at Halicarnassus was constructed. Many magnificent temples

arose in that time, in Asia Minor, the temple at Ephesus, burnt down by

Herostratus, was rebuilt by Alexander’s architect Deinocrates. In the islands

the ruins of the temple of Athena at Priene, of Apollo at Miletus, of

Dionysus at Teos and many others, offered a brilliant testimony to their

former magnificence even to this day. Among Athenian buildings of that

age the Monument of Lysicrates was conspicuous for its graceful elegance

and elaborate development of the Corinthian style. In the succeeding age

Greek architecture showed its finest achievements in the building of

theatres, especially those of Asiatic towns, in the gorgeous palaces of newly-

built royal capitals and, in general in the luxurious completeness of private

buildings. As an important specimen of the last age of Attic architecture the

Tower of the Winds at Athens may also be mentioned.

Finally it is necessary to note that Greek columns were usually

classified according to the Orders of Greek Architecture as the Doric, Ionic

and the Corinthian ones.

Architecture of the Etruscans and the Romans.

In architecture, as well as in sculpture, the Romans were long under

the influence of the Etruscans who, though denied the gift of rising to the

ideal, united wonderful activity and inventiveness with a passion for

covering their buildings with rich ornamental carving. None of their temples

have survived for they built all the upper parts of wood, but many proofs of

their activity in building remained, in the shape of Tombs and Walls. Some

very old gateways, as at Volterra and Perugia exhibited the true Arch of

wedge-shaped stones, the invention of which was probably due to Etruscan

ingenuity and from the introduction of which a new and magnificent

development of architecture took its rise. The most imposing monument of

ancient Italian arch-building can be seen in the sewers of Rome laid down in

the 6th century B.C.

When all other traces of Etruscan influence were being swept away

at Rome by the intrusion of Greek forms of art, especially after the Conquest

of Greece in the middle of the 2nd century B.C., the Roman architects kept

alive the Etruscan method of building the arch which they developed and

completed by the invention of the Cross-Arch and the Dome. With the Arch

the Romans combined, as a decorative element, the columns of the Greek

Orders. Among these their growing love of pomp gave preference more and

more to the Corinthian style. Another service rendered by the Romans was

the introduction of building in brick.

A more vigorous advance in Roman architecture dated from the

opening of the 3rd century B.C. when they began making great military

roads and aqueducts. In the first half of the 2nd century B.C. they built on

Greek models the first Basilica which, besides its practical utility, served to

embellish the Forum. Soon after the middle of the century, the first of their

more ambitious temples in the Greek style appeared. There was simple

grandeur in the ruins of the Tabularium, or Record-Office, built in 78 B.C.

on the slope of the Capitol next the Forum. These were among few remains

of Roman republican architecture. In the last decades of the Republic

simplicity gradually disappeared. Men were eager to display a princely

pomp in public and private buildings as in the first stone theatre erected by

Pompey in 55 B.C. Then all that went before was eclipsed by the vast works

undertaken by Cesar, the Theatre, Amphitheatre, Circus, Basilica fulia,

Forum Cesaris with its Temple to Venus Genetrix.

These were finished by Augustus under whom Roman architecture

reached its culminating point. Agrippa, Augustus’s son in law, a man who

understood building, not only completed his uncle’s plans but added many

magnificent structures - the Forum Augusti with its Temple to Mars Ultor,

the Theatre of Marcellus with its Portico of Octavia, the Mausoleum and

others. Augustus could fairly boast that “having found Rome a city of brick

he left it a city of marble”. The grandest monument of that age and one of

the loftiest creation of Roman art in general, was the Pantheon built by

Agrippa, adjacent to but not connected with his Therme, the first of the

many works of that kind in Rome. A still more splendid aspect was imparted

to the city by the rebuilding of the Old Town burnt down in Nero’s fire, and

by the “Golden House” of Nero, a gorgeous pile, the like of which was

never seen before but which was destroyed on the violent death of its

creator. There was a proof of the luxurious grandeur of private building in

the dwelling-houses of Pompeii, a paltry country-town in comparison with

Rome. The progress made under the Flavian emperors was evidenced by

Vespasian’s Amphitheatre known as the Colosseum. It is the mightiest

Roman ruin in the world even as compared with the ruined Therme (Baths)

of Titus and with his Triumphal Arch, the latter being the oldest specimen of

this class in Rome. But all previous buildings were surpassed in size and

splendour when Trajan’s architect Apollodorus of Damascus raised the

Forum Traianum with its huge Basilica Ulpia and the still surviving Column

of Trajan. No less extensive were the works of Hadrian who, besides

adorning Athens with many magnificent building bequeathed to Rome a

Temple of Venus and Roma, the most colossal of all Roman temples and his

own Mausoleum.

While the works of the Antonines showed a gradual decline in

architectural feeling, the Triumphal Arch of Severus ushered in the period of

decay in the 3'd century A.D. In this closing period of Roman rule the

buildings grew more and more gigantic, as the Baths of Caracalla, of

Diocletian and the palace of the latter at Salona (three miles from Spalatro)

in Dalmatia. The Basilica of Constantine breathed the last feeble gasp of

ancient life.

But outside of Rome and Italy, in every part of the enormous

empire to its utmost barbarian borders bridges, numberless remains of roads,

aqueducts and viaducts, ramparts and gateways, palaces, villas, market

places and judgment-halls, baths, theatres, amphitheatres and temples,

attested the versatility, majesty and solidity of Roman architecture, most of

whose creations only the rudest shocks have hitherto been able to destroy.

VII. Sculpture.

The origin o f painting as an art in Greece was connected with

definite historical personages. That of sculpture was lost in the mists of

legend. It was regarded as an art imparted to men by the gods for such was

the thought expressed in the assertion that the earliest statues had fallen

from heaven. The first artist spoken of by name, Dedalus, who was

mentioned as early as Homer, was merely a personification of the most

ancient variety of art, that was employed solely in the construction of

wooden images of the gods. A series of inventions were attributed to him

that certainly separated far from each other in respect of time and place and

embraced important steps in the development of wood-carving and in the

representation of the human form. Thus he had invented the saw, the axe,

the plummet, the gimlet and glue. He was the first to open the eyes in the

statues of the gods, to separate the legs and to give freer motion to the arms

which had before hung close to the body. After him the early school of

sculptors at Athens, was sometimes called the school of Dedalus. During a

long residence in Crete he instructed the Cretans in making wooden images

of the gods.

The invention of modeling figures in clay from which sculpture in

bronze originated was assigned to the Sicyonian potter Butades of Corinth.

The art of working in metals was known early in Greece as appeared from

the Homeric poems. An important step in this direction was taken by

Glaucus of Chios who invented the soldering of iron and the softening and

hardening of metal by fire and water in the 7th century B.C. The discovery of

bronze-founding was attributed to Rhocus and Theodorus of Samos about

580 B.C. At the same time the high antiquity of Greek sculpture in stone

was represented by a work of the very earliest period of Greek civilization,

that is the powerful relief of two upright lions over the gate of castle at

Mycene (12 century B.C.).

Sculpture in marble, as well as in gold and ivory, was much

advanced by two “pupils of Dedalus,” Dipenus and Scyllis of Crete who

were working in Argos and Sicyon about 550 B.C. and founded an

influential school of art in Peloponnesus. Among their works statues of gods

and heroes were recorded that were often united in large groups.

The statues of Apollo from the island of Thera near Corinth, the

reliefs on the Harpy Monument from the Acropolis of Xanthus in Lycia, in

spite of their archaic stiffness showed an effort after individual and natural

expression though the unemotional and stony smile on the mask-like face

were common to all of them. Even after Greek sculpture had mastered the

representation of the most violent movement, it was still unable to overcome

the lifeless rigidity of facial expression. This was seen in the Trojan battle-

scenes (dated about 480 B.C.) on the Egyptian pediments. Here the figures

were represented in every variety of position in the fight and depicted with

perfect mastery (to the smallest detail), whereas the faces were entirely

destitute of any expression appropriate to their situation. From about 544

B.C. it had become usual to erect statues of the victors in the athletic

contests, Olympia especially having abounded in these. By this innovation

the art was freed from the narrow limits to which it had been confined by the

traditions of religion and led on to a truer imitation of nature.

The period of the finest art was represented by Phidias, Polyclitus

and especially by Myron, another Athenian, in whom the art attained the

highest truth to nature with perfect freedom in the representation of the

human body and was thus prepared for the development of ideal forms. This

last step was taken at Athens in the time of Pericles by Phidias. In his

creations, particularly in his statues of the gods whether in bronze or in

ivory and gold he succeeded in combining perfect beauty of form with the

most profound ideality, having fixed forever the ideal type for Zeus and

Athene, the two deities who were pre-eminently characterized by

intellectual dignity. The perfection of Attic art at this time can be realized

especially when we consider that, with all their beauty of execution, the

extant marble sculptures of the Parthenon, Theseum, Erechtheum, and the

temple of “ Wingless Victory” must be regarded as mere productions of the

ordinary workshop as compared with the lost masterpieces of Phidias.

The school of Phidias had rivals in the naturalistic school which

followed Myron. Independent of both schools stood Callimachus, the

inventor of the Corinthian order of architecture. Another school of sculpture

was founded at Argos by Phidias's younger cotemporary Polyclitus whose

colossal gold and ivory statue of Hera challenged comparison with the

works of Phidias in its materials, its ideality and its artistic form, and

established the ideal type of that goddess. He mainly devoted himself,

however, to work in bronze. His aim was to exhibit the perfection of beauty

in the youthful form. He also established a canon or scheme of the normal

proportions of the body. The first period of Greek sculpture, represented by

Myron, Phidias and Polyclitus, the schools of Athens and Argos held the

first rank beyond dispute. So it was also in the next period which embraced

the 4th century B.C. down to the death of Alexander the Great. Athens,

moreover, during this period remained true to the traditions of Phidias and

still occupied itself mainly with the ideal forms of gods and heroes though in

a spirit essentially altered. The more powerful emotions of the period after

the Peloponnesian War influenced the art enormously. The sculptors of the

time abandoned the representation of the dignified divinities of the earlier

school and turned to the forms of those deities whose nature gave room for

softer or more emotional expression especially Aphrodite and Dionysus and

the circle of gods and demons who surrounded them. The highest aim of

their art was to pourtray the profound pathos of the soul and to give

expression to the play of the emotions. With this was connected the

preference of this school for marble over bronze, as more suited for

rendering the softer and finer shades of form or expression. The art of

executing work in gold and ivory was almost lost, the resources of the States

having no longer sufficed, as a rule, for this purpose. The most eminent of

the New Attic school were Scopas of Paros and Praxiteles of Athens.

Scopas, also famous as an architect, was a master of the most elevated

pathos. Praxiteles was unrivaled master in regard to the softer graces in

female or youthful forms and in the representation of sweet moods of

dreamy reverie. In his statues of Aphrodite at Chidus and Eros at Thespie he

established ideal types for those divinities. The Hermes with the infant

Dionysus, found at Olympia, remained as memorial of his art. We have also

a copy of the Niolid group the original of which was much disputed even in

ancient times whether the author were Scopas or Praxiteles. In contrast to

the ideal aims of Attic art, the Sicyonian school still remained true to its

early naturalistic tendencies and to the art of sculpture in bronze of which

Argos had so long been the home. At the head of the school stood one of the

most influential and prolific artists of antiquity, Lyssipus of Sicyon. His

efforts were directed to represent beauty and powerful development in the

human body. Hence Heracles as the impersonation of human physical

strength was portrayed by him oftener, and with more success than any other

deity. Lysippus was also the most prolific as a portrait sculptor, a branch of

art which had been much advanced in the invention of the method of taking

plaster casts of the features by his brother Lysistratus.

After Alexander the Great the practice of the art which had thus

developed to perfect mastery of technique began to deteriorate with the

general decay of the countries of Greece and to give place to the flourishing

artistic schools of Asia Minor and the neighbouring islands.

The most productive school was that of Rhodes at the head of

whish stood a pupil of Lysippus, Chares of Lindus who designed the famous

Colossus of Rhodes, the largest statue of ancient times. Two well known

extant works in marble proceeded from this school, namely: the group of

Laocoon and his sons by Agesander, Athenodorus and Polydorus found at

Rome in 1506 being now one of the chief treasures of the Vatican Museum,

and the Farnese Bull at Naples. This last group, by Apollonius and

Tauriscus of Tralles, represented the revenge of Zethus and Amphion on

Dirce and was the largest extant antique work which consisted of a single

block of marble. Both these were admirable in skill and technique, having

embodied with the greatest vividness the wild passions of a moment of

horror but the theatrical effect and the exhibition of technical skill were

unduly exaggerated. To the Rhodian school was assigned the group

representing Menelaus bearing the body of Patrocles. It was sometimes,

however, regarded as one of the later products of the same school as the

Group of Niobe that was assigned to the early part of the 3rd century B.C.

The second in rank of the schools of this period was that of

Pergamon where the sculptors Isogonus, Phyromachus, Stratonicus and

Antigonus celebrated the victories of the Kings Eumenes 1 (263-241 B.C.)

and Attalus 1 (241-197 B.C.) over the Gauls in a series of bronze statues.

They are still extant at Venice, Rome and Naples. A magnificent figure of

Attalus, the battle of the Athenians and Amazons, the fight at Marathon, and

the destruction of the Gauls by Attalus can be seen there as well. The other

masterpiece of the school was the work popularly called the Dying

Gladiator, now identified as a Gallic warrior who had stabbed himself after a

defeat. Another one was the group in the Villa Ludovisi called Poetus and

Arria which really represented a Gaul killing his wife and himself. But the

most brilliant proof of their powers was the reliefs of the battle of the Giants

from the acropolis at Pergamon. This work belonged to the most important

artistic products of antiquity. To this period the original of the celebrated

Belvedere Apollo was also referred to. According to the legend rescue of the

temple of Delphi from the Gallic army in 280 B.C. was closely connected

with that particular statue and was supposed to be the work of the god

himself.

After the subjugation of Greece by the Romans in the middle of the

2nd century B.C. Rome became the headquarters of Greek artists whose

work though without novelty in invention had many excellences, especially

in perfect mastery of technique. The works of the artists of the lsl century

B.C. and of the early imperial times were considered more or less free

reproductions of the creations of earlier masters.

There was a revival of Greek art in the first half of the 2nd century

A.D. under Hadrian when a new ideal type of youthful beauty was created,

in the numerous representations of the imperial favourite Antinous.

The artistic work of the Romans before the introduction of Greek

culture was under Etruscan influence. The character of their art seemed

wanting in freedom of treatment and in genuine inspiration. After the

conquest of Greece Greek art took the place of Etruscan one at Rome.

Beside the Greek influence due to which many copies of the

masterpieces of Greek art were gradually accumulated in Rome, a peculiar

Roman art arose. This was especially active in portrait_sculpture. Portrait

statues were divided, according to the fact whether they were in civil togata

or military costume.

It was customary to depict emperors in the form of Jupiter or other

gods while their wives were depicted with the attributes of Juno and Venus.

Of the innumerable monuments of this description special attention must be

paid to the statue of Augustus in the Vatican and the bronze equestrian

statue of M. Aurelius on the square of the Capitol at Rome.

Among the Greeks painting developed into an independent art

much later than sculpture though it was used very early for decorative

purposes. This is proved by the evidence of painted vases belonging to the

ages for the most primitive civilization and by the mural paintings

discovered by Schliemann at Tiryns. The scanty notices in ancient authors

respecting the first discoveries in this art connected it with historical persons

and not with mythical names as in the case of sculpture. Thus it is said that

either Philocles, the Egyptian, or Cleanthes of Corinth was the first to draw

outline sketches; that Telephanes of Sicyon developed them further; and that

Eumarus of Athens (in the second half of the 6th century B.C.) distinguished

man and woman by giving the one a darker, the other a lighter colour.

Cimon of Cleona is mentioned as the originator of artistic drawing in

profile. It is further said of him that he gave variety to the face by making it

look backwards or upwards or downwards, and freedom to the limbs by duly

rendering the joints; also that he was the first to represent the veins of the

human body, and to make the folds of the drapery fall more naturally.

Painting did not however make any decided advance until the

middle of the 5th century B.C. This advance was chiefly due to Polygnotus

of Thasos who painted at Athens. He gave greater variety of expression to

the face which before had been rigidly severe. His works, most of them

large compositions rich in figures, give evidence of a lofty and poetic

conception. They were generally mural paintings for decorating the interior

of public buildings. The drawing and the combination of colours were the

chief considerations; light and shade were wanting, and no attention was

paid to perspective. Besides mural paintings there were pictures on panels

such as afterwards became common.

The Athenian Apollodorus (about 420 B.C.) was the actual founder

of an entirely new artistic style. He was the first, says Pliny, to give his

pictures the appearance of reality. He also led the way in the proper

management of the fusion of colours and their due gradation in different

degrees of light and shade.

The Attic school flourished till about the end of the 5th century B.C.

when this art was for some time neglected at Athens but made another

important advance in the towns of Asia Minor, especially at Ephesus. The

principal merits of this, the Ionic school, consisted in richer and more

delicate colouring, a more perfect system of pictorial representation. Its

principal representatives were Zeuxis of Heraclea and Parrhasius of

Ephesus; Timanthes also produced remarkable works, though not an

adherent of the same school. It was opposed by the Sicyonian school,

founded by Eupompus of Sicyon, and developed by Pamphilus of

Amphipolis, which aimed at greater precision of technical training, very

careful and characteristic drawing and a sober and effective colouring.

Greek painting reached its summit in the works of Apelles of Cos and

Protogenes of Caunos in the second half of the 411' century B.C. They knew

how to combine the merits of the Ionian and Sicyonian schools, the perfect

grace of the former with the severe accuracy of the latter.

After the age of Alexander, the art of painting was characterized by

a striving after naturalism, combined with the representation of common,

every-day scenes, and of still-life. This branch of painting was also carried

to great perfection, and Piraicus was the most celebrated for it. Among

painters of the loftier style the last noteworthy artist was Timomachus of

Byzantium.

Among the Romans a few solitary names of early painters are

mentioned, for instance, Fabius Pictor and the poet Pacuvius; but nothing is

known as to the value of their paintings, which served to decorate buildings.

The way in which landscapes were represented by a certain S.Tadius in the

reign of Augustus is mentioned as a novelty. These landscapes were mainly

for purposes of decoration. Indeed the love of display peculiar to the

Romans had led them gradually to accumulate the principal works of the old

Greek masters at Rome as ornaments for their public and private edifices

and brought about an extraordinary development of decorative art. The

principal subjects represented at these paintings were figures from the world

of myth, such as Centaurs, Satyrs, scenes from mythology and heroic

legends, frequently copies of famous Greek originals, landscapes, still-life,

animals and also scenes from real life. From a technical point of view these

works did not go beyond the limits of light decorative painting. They were

especially wanting in correct perspective. But they showed fine harmony,

varied gradation, and delicate blending of colour. Nevertheless they

frequently demonstrated a surprising depth and sincerity of expression:

qualities which characterized the lost masterpieces of the ancient artists and

gave us a very high idea of them. One of the finest mural paintings was so

cold the Aldobrandini Marriage named after its first owner. Cardinal

Aldobrandini, (now in the Library of the Vatican at Rome). It was copied

from an excellent Greek original, and represented in the style of relief the

preparations for a marriage. It exhibited several individual motives of much

beauty; its colouring was soft and harmonious; and it was instinct with that

placid and serious charm which belonged only to the antique. In technical

execution, however, the work was insignificant.

The Vatican Library also possesses an important series of

landscapes from the Odyssey, found during the excavations on the Esquiline

in 1848-1850. Landscapes of this kind were mentioned by Vitruvius among

the subjects with which corridors used to be decorated in the good old times.

They represented the adventure with the Lastrygones, the story of Circe and

the visit of Odysseus to the realm of Hades, thus they illustrated a

continuous portion of the poem. The predominant colours were a yellowish

brown and a greenish blue, and the pictures were divided from one another

by pilasters of a brilliant red. They furnish interesting examples of the

landscape-painting of the last days of the Republic or the first of the Empire

and, in point of importance stood alone among all the remains of ancient

painting. The processes of painting are represented in several works of

ancient art, e.g. in three mural painting from Pompeii.

Appendix I.

A.

Achaean /a'ki(i:)an/ ахейцы

Achilles /a'kili:z/ Ахиллес

Actium /'aektiam/ Акциум

Agamemnon /asga'memnan/ Агамемнон

Aeetes /i:'i:ti:z/ Ээт, бог солнца

Aegisthus /i:gis0as/ Эгистес

Aeneas /i(i:)'ni:aes/ Эней

Aeneid /'i:niid/ Энеида (поэма)

Aeschylus /'i:skilas/ Эсхил

Aeolus /'i(i:)aolas/ Эол (бог ветра)

Aesop /'i:sop/ Эзоп

Ajax /'aidgasks/ Аякс

Alceus /'aslkias/ Алкей

Alcinous /ael'sinauas/ Алкиной

Alexandrine Plead /aalig'zaandrain pli:d/ поэты Александрийской

Плеяды

Amores /'aemoris/ поэма Овидия

Amphitrite /'eemfitraiti/ Амфитрита

Amyntas II / 'asmintas/ Аминтас Второй, император

Anacreon /an'aakrian/ Анакреон

Anaxagoras /aenask'saegaras/ Анаксагор

Anchises /aerj'kaisi:z/ Анхиз

Andromache /агп dromaki/ Андромаха, жена Гектора

Antigone /sen tigsni/ Антигона

Antipater /aen'tipata/ дьявол

Antoninus /senta nainos/ Антонин, император

Antonius /aen'tounjas/ Антоний, император

Antoninus Pius /ffinta nainas-'paias/Антоний Пий, император

Apennines /'aepanins/ Апеннины

Aphrodite /aefra'daiti/ Афродита (рим.Венера)

Apollo /a'polou/ Аполлон (греч.Аполлон)

Appian / aepian/ Апиан

Apuleius /'aspjuleias/ Апулей

Aratus /'aerates/ Эратус

Ares /sariz:/ Apec (рим. Марс)

Argonauts/'a:gano:ts/ аргонавты

Archimedes /a:ki'mi:di:z/ Архимед

Aristophanes /aeris'tofanilz/ Аристофан

Aristotle /'aeristotl/ Аристотель

Arrian /'aerian/ Ариан

Artaxerxes II /a:tag z3:ksi:z/ Артаксеркс Второй, император

Artemis /'altimis/ Артемида (рим. Диана)

Ascanius /aes'keinjas/ Ac кап и it

Asclepius /aes'kli :pius/ Асклепий

Atellana /'aetalana/ Ателанна (фарс)

Athenae /ae0i'ni/ Афины (reorp.)lat.

Athenaeum /aeGi niam/ Атенеум

Athene /э'бкш/Афина (рим. Минерва)

Atreus /'eitriu:s/ Атрей

Attic Era /'aetik Чага/ Античная эра

Augustus, Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus

/o:'gstas 'gaias 'dgirlias 'si:za ok'tevjanas/

Октавиан Август, император

Avicenna /aevi'sena/ Авиценна

В.

Bethlehem /'beGilem/ Вифлеем (reorp.)

Bithynia /'biGinia/ Бисиния (reorp.)

Boethius /bau'i:Gjas/ Боэций

Boetia /bi'aujja/ Беотия (reorp.)

bucolics/bjo(u:)koliks/ буколическая поэзия

buffoonery /ba'fu:nari/ шутовство

C.

Cailimachus /'kalimakas/ Каллимах

Caligula /кэ ligjob/ Калигула, император

Callikrates /ka'likratkz/ Калликрат

Calypso /'kaslipsau/ Калипсо

Capitoline /ka'pitalain/ Капиталийский (холм)

Carthage / ka:Gidg/ Карфаген (reorp.)

Catiline /'kastilain/ Катилина

Ceres /'siari:z/ Церера (греч. Диметра)

Chalcis /'kaelsis/ Колхида (reorp.)

Charlemagne / ’Jadamain/ Карл, император

Chios /'kaios/ Хиос (reorp.)

Cicero /'sisarau/ Цицерон

Circe /'s3:si/ Цирцея

Cleon /'klian/ Клеон

Clytemnestra /klaitim’nestra/ Климнестра

Colophon /'kolafan/ Колофон (reorp.)

Constantine /'konstantain/ Константин, император

Constantinople /konstaenti'naupl/ Константинопль

cout-de-etats /kuida'ta: / государственный переворот

Crassus /'krassas/ Kpacc

Creon /'krian/ Kpeon

Croesus /'kri:sas/ Крез

Cybele /'sibil/ Кибела (рим.Рея)

Cyclop Polyphemus / saiklop poli'fumas/ циклоп Полифем

D.

Danaus / daenasas/ Даная

defile /di: fail/ загрязнять

Delphi / delfai/ Дельфы (reorp.)

Demeter /di'mi:ta/ Деметра (рим. Церера)

Democritus /di'mokritas/ Демокрит

Demosthenes /di'mos8ani:z/ Демосфен

Diana /dai аепэ/ Диана (греч. Артемида)

Dido/'daidau/Дидона, королева Карфагена

Dionysus /daia’naisas/Дионис

Dyskolos /'diskalas/ Дискобол

E.

Eileithyia /'ailei0ia/ Илисия

Electra /i'lektra/ Электра

elegiac /eli'dgaiak/ элегия

Empedocles /em'pedaklr.z/ Эмпедокл

Eos /'i:as/ Ио (заря)

Epicurus /epi'kjuaras/ Эпикур

Epir /e'paia/ Эпир, (reorp.)

epistles /i 'pislz/ письма (lat.)

Erechteum /erek 9i:am/ Эрехтейон

Erinyes /'iarinis/ эринии

Etruscan /i'traskan/ этруски

Euboea /ju: 'bia/ Эвбея (reorp.)

Euclid / ju:klid/, Euclides / ju:klidaz/ Эвклид

Eumahus / 'jumahas/ Эмахус

Eumenides /'juminaidis/ Эвмениды

Euripides /joa'ripidi:?/ Эврипид

F.

fleece /fli:s/ овечья шерсть

forfeited / ’fo:fitid/ утраченный

Galen /'geilin/ Гален

Ganymede /'ga:nimi:d/ Ганимед

Gaul /go: 1/ Галл

georgics /'dgo:dgiks/ георгики

H.

Haemon /'heman/ Гемон

Hades /'heidiiz/ Ад (рим. Плутон)

Hadrian /'heidrian/ Адриан, император

Hebe /'hi:bi/ Гебе

Hecate /'hekati(:)/ Геката

Hecuba / 'hekjuba/ Гекуба

Hecyra / hekira/ Гекира

hegemony /hi'gemani/ гегемония

Helios /'hiilios/ Гелиос, бог солнца

Hephaestus /hi'frstas/ Гефест( рим. Вулкан)

Heraclitus of Ephesus /hera'klaitas efisas/ Гераклит Эфесский

Herackes / herakli:z/ Геракл

Hermes /'ha:mi:z/ Гермес (рим.Меркурий)

Herodotus /he'rodatas/ Геродот

Heroides /be'roudies/ царь Ирод

Hesiod /'hirsiod/ Гесиод

Hipparchus /hi'pa:kas/ Гиппарх

Hippocrates /hi pokrati:?/ Гиппократ

Hippolytus /hi'politas/ «Ипполит», пьеса Эврипида

Homer /'hauma/ Гомер

Horace, Quintus Horatius Flaccus /'horas kwintas ‘horajjas flaskas/

Гораций

i.immolate /'imauleit/-npHHOCHTb в жертву

iniquity /ГшкУ1>М/-несправедливость

Ionian /ai'ounjan/ (n.)

Iphigenia /ifidgi'naia/ Ифигения

Iris /'aiaris/ Ирис

Isis /'aisis/ Изис

Ithaca /'iGaka/ Итака (reorp.)

J.

Janus /'dgeinas/ Янус

Jason /'dgeisn/ Ясон

Juno /'dgu:nou/ Юнона (греч.Гера)

Judaea /dgui 'dia/ Иудея (reorp.)

Jupiter/'dgu:pita/ Юпитер (греч. Зевс)

jurisprudence /'dgoarispru:dens/ юриспруденция

Justinian /dgas'tinian/ Юстиниан, император

Juvenal /'dgu:vinl/ Ювенал

L.

Laestrygones /li:s'traigani:z/ Лестригоны

Lares and Penates / ’leari.z aend pe'neitirz/ Лары и Пенаты

Latinus /ta'tainas/ Латин, царь

Leda /'li:de/ Леда

Livius Andronieus /'aendro'naikas/ Ливий Андроник

Livy,Titus Livius - /"livi/ Тит Ливий

love-potion /'lav рэо!эп/-любовное зелье

Lucanus /'luikanas/ Лукан

Lucian /'lu:sjan/ Лукиан

Lucilius /lu: silias/ Луций

Lucretius, Titus Lucretius Carus /lu:'kri:fjos 'taitss Iu:'kri:jj3s 'kearas/

Тит Лукреций Кар

Lupercalia /1и:рз: 'keiljs/ праздник Луперкалий

Lyceum /lai'siam/ Ликеум

Lycurgus /lai'k3:gas/ Ликург

lyre /'laiara/ лира

M.

Maecenas /mi(i:)'si:naes/ Меценат

Marcus Aurelius /'ma.kas o:'ri:ljas / Марк Аврелий, император

Mars /ma:z/ Марс (греч.Арес)

Martial /'majjal/ Марциал

Menander /mi'naenda/ Менандр

Menelaus /meni'leias/ Менелай

Mercurius /'m3:kjurias/ Меркурий (греч. Гермес)

Metamorphoses /meta'moifauziz/ Метаморфозы, поэма Овидия

Moeroe / mo:ro:/ Мойры

Muses /mjuiziz/ Музы

Mycenae /mai'si:ni(i:)/ Микены (reorp.)

N.

Nemesis / nemisis/ Немезиды

Nereid /'niariid/ Нереид

Nereus /'niarjurs/ Нерей

Nero /'niarau/ Нерон, император

Nike /'naiki:/ Ника

О.

Oceanus /ou'sianas/ Океан

Odeon /'oudjan/ Одеон

Odysseus /a'disju:s/ Одиссей

Odyssey /'odisi/ Одиссея (поэма Гомера)

Oedipus /'i:dipas/ Эдип

Orestes /o'resti:z/ Орест

Ovid, Publius Ovidius Naso /'ovid publias ovidas ‘naesau/ Публий

Овидий Назон

P.

panegyric /paeni'dgirik/ панегирик

pantomimus /'paentamimas/ пантомимы

Parthenon /'ра:0тэп/ Парфенон

Peloponnesian /pibpo'nijan/ пелопонесский

Penelope /pi'nebpi/ Пенелопа

Pericles /'periklkz/ Перикл

Persephone /pai'sefani/ Персефона

Phaedrus/'fi:drss/ Федр

Phidias /'fidises/ Фидий

Philoctetes /fibk'ti:ti:z/ Филоктет

Plato /'pleitau/ Платон

Plautus, Titus Maccius /"plo:tas 'taibs/ Тит Макций Плавт

Plutarch /'plu:ta:k/ Плутарх

Pomona /рэ'тэипэ/ Помона

Pompeia /pom'pi(i:)3/ Помпея

Poseidon /po'saidsn/ Посейдон (рим.Нептун)

Priam /"prabm/ Приам

Priapus /prai'eipas/ Приап

Prometheus Bound /pra'mi:0ju:s baond/ Прометей прикованный

Propertius /pr3’p3:jj3s/ Проперций

Propylaeum /propi'П:эт/ Пропилеи

Protagoras /prso'tegaraes/ Протагор

Pylades /'pibdi:z/ Пилад

Pythagoras /pai'0seg3rass/ Пифагор

Q-Quirinus /kwi'rainss/ Квприны

refuge /'refju:dg/ убежище

Remus /'ri:mas/ Рем (брат Ромула)

Rhea /п:э/ Рея

Rhodes /roudz/ Родос (reorp.)

ritual hymn /'ritjusl himn/ ритуальный гимн

Romulus / ‘romjulas/ Ромул (основатель Рима)

S.

Sappho /'saefэо/ Сафо

Saturnus/'saetanus/ Сатурн

Satyrs /'sastaz/ сатиры

Scythians /skiGianz/ скифы

Selene/si'li:ni/ Селена

Seleucid Asia /si'lju:sid eija/ королевство

Servius Tiberius /'s3:vias tai'biarias/

Silvanus /sil'veinas/ Сильван

Smyrna /'sm3:na/ Смирна (reorp.)

Socrates /'sokratiiz/ Сократ

Solon /'saulon/ Солон

Sophocles / sofakli:z/ Софокл

Suetonies /swi:'taonjas/ Светоний

Syracuse /'saiarakju:z/ Сиракузы

т.Tacitus, Gaius Cornelius /'taesitas 'gaias ko:'ni:ljas/ Тацит, Гай

Корнелий

Tarquinius /ta:'kwinias/ Тарквиний

Telemachus /ti'lemakas/ Телемах, сын Одиссея

Thebes /0i:bz/ Фивы (reorp.)

Themis /Gi'mis/ Фемида

Themistocles /0i'mistakli:z/ Фемистокл

Theocritus /0i okritas/ Теокрит

Theodosius /0ia'dausjas/ Феодосий

Theseus /'0i:sjus/ Тезей

Thrace /8reis/ Фракия

Thucydides /0jo(u:)'sididi:z/ Туцидид

Tiberius /tai'biarias/ Тиберий, император

Tibullus /ti'balas/ Тибул

Titan /'taitan/ титан

Titus /'taitas/ Тит, император

Trajan / ’treidgan/ Траян, император

Triton /'traitn/ Тритон

triumvirate /trai'amvirit/

Troy /troi/ Троя

U.

Umbria /'ambria/ Умбрия (reorp.)

Uranus /juaranas/ Уран

Vergil, Publius Vergilius Maro /'v3:dgil V3:dgiljas maero/ Публий

Вергилий Марон

Venus /'viinas/ Венера, (греч. Афродита)

vernacular /va'naekjob/ местный, туземный язык

Vespasian /ves'peisjan/ Веспасиан

Vulcanus/'valkanos/ Вулкан (греч.Гефест)

X.

Xenophanes /'zenafanis/ Ксенофан

Xenophon /'zenafan/ Ксенофон

Z.

Zeno /'zi:nao/ Зенон

Zeus /zju:s/ Зевс (рим. Юпитер)

Appendix II.

Пропилеи. Восточный портик. Вид на город с Акрополя.

Архитектор Калликрат. Храм Ники Аптерос на Афинском Акрополе.

Мрамор. Закончен в 421 г. до н.э.

Афинский Акрополь. Реконструкция.

Forum Romanum,

1 - стереобат

2 - стилобат

3 - колонна

4 - база

5 - фуст - ствол колонны

6 - каннелюры

7 - энтазис

8 - капитель

9 - абак

10 - эхин

11 - волюта

12 - антаблемент

13 - архитрав

14 - фриз

15 - триглиф

16 - метопа

17 - карниз

18 - фронтон

19 - акротерий

20 -сима

1. O.Seyffert, A dictionary of classical antiquities: mythology, religion,

literature, art. Oxford university press, 1957.

2. J.J. Pollit. Art at the Hellenistic Age, Cambridge University Press, 1987.

3. Martin Robertson, History of Greek Art, Cambridge University Press,

1957.

4. John Boardman, Greek Art, London, 1975.

5. Upjohn Wingert, Manler, History of world Art, Oxford University Press,

1958.

6. The outline of art, Ed. by Sir William Orpen, London, 1957.

7. Sir Lawrence Gowing, A history of art Macmillan, London 1983.

8. H.W Janson, History of Art, New York, 1977.

9. W.J.Durant, The life of Greece, New-York, 1966.

10. O.Taplin, Greek Fire, New-York, 1990.

11. Виппер Б. P., Искусство Древней Греции, M., 1972.

12. Всеобщая история архитектуры, Т.2., М., Стройиздат, 1973.

13. Всеобщая история искусств, Т. 1. Под редакцией Чегодаева А. Д.,

М., Искусство, 1956.

Учебно-методическое издание

ЛЛШИНА Любовь Арнольдовна

Ancient culture of Greece and Rome

Part II. Arts.

Методические указания

Подписано в печать - 2 3 . 03, Об, Заказ - /О Э ,

Уел. - печ. л .-3 ,5 изд. № 290-06

Формат - 60x84/16 тираж - 400,

127994, Москва, ул. Образцова, 15.

Типография МИИТа