An Assessment of Song Admixture as an Indicator of ... · Key words: Black-capped Chickadee,...

Transcript of An Assessment of Song Admixture as an Indicator of ... · Key words: Black-capped Chickadee,...

Liberty UniversityDigitalCommons@Liberty

University

Faculty Publications and Presentations Department of Biology and Chemistry

2007

An Assessment of Song Admixture as an Indicatorof Hybridization in Black-capped Chickadees(Poecile atricapillus) and Carolina Chickadees(Poecile carolinensis)Gene D. SattlerLiberty University, [email protected]

Patricia Sawaya

Michael J. Braun

Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/bio_chem_fac_pubs

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Biology and Chemistry at DigitalCommons@Liberty University. It hasbeen accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Liberty University. Formore information, please contact [email protected].

Recommended CitationSattler, Gene D.; Sawaya, Patricia; and Braun, Michael J., "An Assessment of Song Admixture as an Indicator of Hybridization in Black-capped Chickadees (Poecile atricapillus) and Carolina Chickadees (Poecile carolinensis)" (2007). Faculty Publications andPresentations. Paper 34.http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/bio_chem_fac_pubs/34

The Auk 124(3):926-944, 2007© The American Ornithologists' Union, 2007.Printed in USA.

AN ASSESSMENT OF SONG ADMIXTURE AS AN INDICATOR OFHYBRIDIZATION IN BLACK-CAPPED CHICKADEES {POECILE

ATRICAPILIUS) AND CAROLINA CHICKADEES (P. CAROLINENSIS)

GENE D . SATTLER,^'^-^ PATRICIA SAWAYA,''' AND MICHAEL J. BRAUN^-^

^Department of Vertebrate Zoology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution,42J0 Silver Hill Road, Suitland, Maryland 20746, USA; and

-Department of Biology, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland 20742, USA

ABSTRACT. —Vocal admixture often occurs where differentiated populations orspecies of birds meet. This may entail song sympatry, bilingually singing birds,and songs with intermediate or atypical characteristics. Different levels of vocaladmixture at the range interface between Black-capped Chickadees (Poecile atri-capillus) and Carolina Chickadees (P. caroUnensls) have been interpreted as indi-cating that hybridization is frequent at some locations but not others. However,song ontogeny in these birds has a strong nongenetic component, so that infer-ences regarding hybridization based on vocal admixture require confirmation. Weused diagnostic genetic markers and quantitative analyses of song to character-ize population samples along two transects of tbe chickadee contact zone in theAppalachian Mountains. More than 50% of individuals at the range interface wereof hybrid ancestry, yet only 20% were observed to be bilingual or to sing atypicalsongs. Principal component analysis revealed minimal song intermediacy. Thisresult contrasts with an earlier analysis of the hybrid zone in Missouri that foundconsiderable song intermediacy. Re-analysis of the Missouri data confirmed thisdifference. Correlation between an individual's genetic composition and its songtype was weak in Appalachian hybrid populations, and genetic introgression inboth forms extended far beyond the limits of vocal admixture. Therefore, song isnot a reliable indicator of levels of hybridization or genetic introgression at thiscontact zone. Varying ecological factors may play a role in producing variable lev-els of song admixture in different regions of the range interface. RcceizK'd 18 October2004, accepted 6 August 2006.

Key words: Black-capped Chickadee, Carolina Chickadee, hybrid zone,intermediacy, introgression, Poecile atricapillus, P. carolinensis, song admixture.

Una Evaluacion de la Mixtura de Cantos como Indicador de Hibridacion en Poecileatricapillus y P. caroliitensis

RESUMEN. —La mixtura vocal ocurre usualmente donde poblacionesdiferenciadas o especies de aves se encuentran. Esto puede impHcar simpatria enlos cantos, aves bilingiies en sus cantos y cantos con caracteristicas intermediaso atipicas. Los diferentes niveles de mixtura vocal en la interfase de los rangosde Poecile atricapillus y P. carolinensis han sido interpretados como indicadoresde que la hibridacion es frecuente en algunas localidades, pero no en otras. Sin

'Present address: Department of Biology and Chemistry, Liberty University, 1971 University Boulevard,Lynchburg, Virginia 24502, USA, E-mail: [email protected]• Deceased.

926

July 2007] Chickadee Song Admixture 927

embargo, la ontogenia del canto en estas aves presenta un fuerte componente nogenetico, por lo que las inferencias sobre la hibridacion basadas en la mixturade vocalizaciones requieren ser confirmadas. Usamos marcadores geneticosdiagnosticos y analisis cuantitativos de los cantos para caracterizar las muestraspoblacionales a lo largo de dos transectas de la zona de contacto entre lasespecies de estudio en las Montafias Apalaches. Mas del 50% de los individuosde la interfase de los rangos fueron de origen hibrido, aunque se observo quesolo el 20% de los individuos fueron bilingiies o cantaron canciones atipicas.Analisis de componentes principales revelaron que los cantos intermedios fueronminimos. Estos resultados contrastan con un analisis anterior de la zona hibridade Missouri que encontro niveles considerables de cantos intermedios. E! re-analisis de Ios datos de Missouri confirma esta diferencia. La correlacion entrela composicion genetica de los individuos y su tipo de canto fue debil en laspoblaciones hibridas de los Apalaches, y la introgresion genetica en ambas formasse extendio considerablemente mas alia de los limites de la mixtura de voces. Porlo tanto, los cantos no son un indicador confiable de los niveles de hibridacion o deintrogresion genetica en esta zona de contacto. Los factores ecologicos cambiantespodrian jugar un papel en producir niveles variables de mixtura de cantos endiferentes regiones de la interfase de los rangos.

HYBRIDIZATION IN BIKDS is relatively wide-spread (Grant and Grant 1992) and provides thepotential for genetic exchange between taxa. Yetspecies-specific visual and vocal communicationsystems usually function to ensure assortativemating and reproductive isolation (Paterson1985, Gill 1998). Because such avian communi-cation systems rely heavily on imprinting andother forms of learning, however, they are sus-ceptible to breakdown. Contact zones betweenrelated taxa with similar recognition systemsare a case in point. The physical proximity ofdifferentiated taxa at tbe contact zone providesopportunities for misdirected imprinting andlearning that can lead to interbreeding, withtbe subsequent potential for genetic exchangebetween them. In birds, plumage intermediacyusually provides clear evidence of such events(Rising 1983).

Black-capped Chickadees (Poecile atricapillus)and Carolina Chickadees (P. carolinensis) sharean extensive contact zone across the easternhalf of North America where the potential forgenetic exchange exists (Brewer 1963, Mostromet al. 2002, Curry 2005), They also share asimilar vocal repertoire (Smith 1972, Ficken etal. 1978, Hailman 1989; but see Hailman andFicken 1996). Because the plumage and men-sural differences thaf distinguish the two aresubtle, the first evidence usually noted tbatsuggests possible hybridization between them

is not morphological intermediacy, but vocaladmixture, including sympatry of song types,presence of birds singing atypical or interme-diate songs, and bilingual birds that sing bothspecies' songs (Brewer 1963, Johnston 1971,Ward and Ward 1974, Robbinsetal. 1986). Whenthese behavioral observations are followed bydetailed morphological analyses, subtle inter-mediacy is typically revealed that supports theconclusion that hybridization is present (Brewer1963, Rising 1968, Johnston 1971, Robbins et al.1986, Sattier and Braun 2000).

On the other hand, at other portions of thecontact zone between atricapillus and carolin-ensis, a minimal level of atypical singing andmorphological intermediacy has been found,leading to the conclusion that hybridizationbetween them is rare or absent at these locations(Tanner 1952; Brewer 1963; Merritt 1978, 1981;but see Grubb et al. 1994). However, because ofthe central role of learning in song ontogeny,song can be an unreliable marker of hybridiza-tion and introgression in some songbird hybridzones (Ficken and Ficken 1967, Emlen et al.1975), given that social interactions among indi-viduals shape song development (Payne 1981,Payne and Payne 1997), Likewise, a numberof factors can make levels of morphologicalintermediacy an imperfect and even misleadingmeasure of genetic interactions between taxa,especially when two forms are similar (Sattier

928 SATTLER, SAWAVA, AND BRAUN [Auk, Vol. 124

and Braun 2000 and references therein). Theecological setting of a hybrid zone can also varygeographically and influence the interactionsbetween taxa at different locations (Cook 1975,Grubb et al. 1994). This may lead to geographi-cally varying levels of vocal intermediacy thatare unrelated to levels of hybridization.

Molecular genetic analyses offer a means ofmore accurately assessing genetic interactionsbetween hybridizing taxa. Species-specificmarker loci are now available that are diag-nostic for atricapillus and carolinensis (Mack etal. 1986; Gill et al. 1989, 1993; Sawaya 1990;Sattier 1996). Use of these markers to probethe genetic structure of their contact zone hasrevealed a high proportion of hybrids in thecenter and extensive introgression across thecontact zone at each location studied, includ-ing Missouri, Virginia, West Virginia, and Ohio(Sawaya 1990, Sattier 1996, Sattier and Braun2000, Bronson et al. 2005). Comparison of mor-phometric and genetic variation in Virginia andWest Virginia showed that, on a broad scale,there is concordance between morphology andgenes. However, the genetic markers detectedmore hybridization and introgression thanwas indicated by morphological analysis alone(Sattier and Braun 2000). Accurate assessmentof genetic ancestry helped demonstrate thatendogenous selection because of genetic incom-patibility is largely responsible for maintainingthe hybrid zone (Bronson et al. 2003a, 2005) andthat social dominance of males is more impor-tant than genetic ancestry in female mate prefer-ence (Bronson et al. 2003b).

Here, we examine vocal and genetic variationacross Virginia, West Virginia, and Missouritransects of the chickadee hybrid zone toassess the reliability of song as a marker ofhybridization. Such an assessment is especiallyimportant for a contact zone in which evenmultivariate analyses of morphology are inad-equate to assess hybridization, because vocalintermediacy is then relied on to make suchestimates. Our analysis reveals that song typeis not a good indicator of genetic ancestry ofindividual chickadees in and near the hybridzone. Although hybridization is extensive oneach transect, the degree of vocal admixturevaries. We suggest that this variation may berelated to differences in the abruptness of eco-logical transitions at the range interface on thethree transects.

METHODS

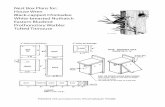

Population samples.—We studied singingbehavior of chickadees during April-July,1989-1992, at 12 sites that comprise two transects(Fig. 1 and Table 1). The transects crossed thecontact zone in the Appalachian Mountains, oneon the eastern slope (Virginia transect) and oneon the western slope (West Virginia transect).Morphological and genetic variation of chicka-dee populations at these sites was described bySattier and Braun (2000), and detailed locali-ties can be found therein. Nine sites representclosely spaced samples of the hybrid zone onthe two transects (VA1-VA5 and WV1-WV5).Allopatric population samples of carolinensis (VAand OH) served as terminal parental populationsof carolinensis for the Virginia and West Virginiatransects, respectively (Fig. 1). Initially, a singlesite (VAIAVVI) from tbe central Appalachiansserved as a common terminal population ofatricapillus for both transects. However, becausebirds at this site showed evidence of geneticintrogression from carolinensis (Sattier and Braun2000), we added a more distant allopatric sample(PA) in northern Pennsylvania to represent pureparental atricapillus. We then treated PA as a ter-minal population sample of both transects.

At each site, we located chickadees visu-ally, by their spontaneous calls or song, or byresponse to a playback tape. Birds were usuallyencountered in pairs. After locating birds, weevaluated tbe vocal response of males to play-back of both atricapillus and carolinensis song. Inpopulations where atricapillus song predomi-nated, 2 min of carolinensis song was broadcast,followed by 2 min of silence, then 2 min of atri-capillus song. In populations where carolinensissong predominated, the order of song presenta-tion was reversed. In WV3, where both species'songs were common, we alternated the order ofsong presentation.

During and following responsiveness trials,we recorded samples of whistled song usinga Sony TCM-5000EV cassette recorder witha Sennheiser ME-80 shotgun microphone. Ifa bird sang more than one type of song, aneffort was made to record each song type sung.Collecting birds for genetic and morphometricanalyses was crucial, however, so recording ses-sions were not lengthy (usually 5-20 min), andsong types recorded from a given bird do notnecessarily represent its full repertoire.

July 20071 Chickadee Song Admixture 929

FIG. 1. Range of Poecile atricapillus and P. carolinensis in the Appalachian region and locations ofstudy sites that comprise the Virginia and West Virginia transects, including parental samples OH,PA, and VA. Exact localities are given in Sattler and Braun (2000). Range boundaries are approxi-mate (Peterjohn 1989, Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries-Virginia Society ofOrnithology 1989, Brauning 1992, Buckelew and Hall 1994).

An additional transect crossing the contactzone in Missouri (Table 1) has previously beenanalyzed vocally (Robbins et al, 1986) andgenetically (Sawaya 1990). We re-analyzed vocaldata from that transect for comparison with ourAppalachian samples. The Missouri transectcomprised six samples: an atricapillus referencesample from northwestern Missouri (MO), acarolinensis reference sample from Louisiana(LA), and four samples from near the hybridzone in southwestern Missouri (MO1-MO4;see also Robbins et al. 1986, their figure 1).Robbins et al. (1986) restricted vocal analysesto MO1-MO4, combining MOl and MO2 asa reference atricapillus sample, and we treatedthem similarly.

Song types. —We classified songs into songtypes based on discontinuous variation in num-ber, structure, and pattern of notes (Kroodsma1982, Nowicki et al. 1994). Within a song type,there was more limited variation, mainly infrequency and duration characteristics ofhomologous notes. We found this classificationpreferable to that of Robbins et al. (1986), whodesignated song types solely by the number ofnotes in a song, because that method sometimes

lumps songs that differ appreciably in frequencyor patterning into a single song type. When anindividual sang more than one song type, songsof each type were treated separately as songbouts. Song was analyzed from 133 individu-als from the Appalachian transects, all of whichwere sexed as males by examination of gonads,with the exception of one male sexed geneticallyby the method of Griffiths et al. (1998) and threesinging individuals that were not collected.Nineteen individuals sang more than one songtype, and so were represented more than oncein song analyses. We analyzed 157boutsof songfrom these Appalachian birds (Table 1; see alsotable 6 in Sattler 1996). A total of 88 song boutsfrom 56 individuals from Missouri populationsMO1-MO4 was re-analyzed here (Table 1; seealso table 8 in Sattler 1996). Thirteen of theseindividuals sang more than one song type, andso were represented more than once in songanalyses.

The song of atricapillus consists of twowhistled notes (Fig. 2), the first slightly higherin pitch than the second (Dixon and Stefanski1970), and is highly stereotypic throughout mostof the bird's range (Hailman 1989, Kroodsma et

930 SATTLER, SAWAYA, AND BRAUN [Auk, Vol.124

-au

£

01

x:

a;

1/

"ft

o;x>S;32

'Cx>x;

C

uO

o

co

•ac

MI

o

ora N

Xi S-

II

3 C

D..2cS:2

X) ID

O O

p O O r-<d iri iri 00

n

O O O(N r-j rN

o o ^ PN i>» ind d iri rj o6 (S

>

_ ~> r j CD ri- in

p- > >

(N O O C

OS ^ 00 SO

•XI

O O O LO

O O cnrsi (N m

o o o Ln ^O O CO ^4" 1—'

o in so !>,.

> > > > > >

3XI

g(J

01

II

Q . .

o

00 p-^ d

sOCO

p p p iri in inO 0 0 T-" CT\ sO ON

I— m in <?• o(N (N rj {N (N

-1 fN m ^

o o o o o

o

c01

ra

a

a3ra

bee

ted

ra

ntei

<uao

in

'ocu

o

£JJ,- o a.

iiliSg •— ,w u(> > tn C^^ C_ n> ra

o b

ra ot " ^ * - '— JS

g ,E 9c,£ c E>2 o< •;: B c ^ u .

ra >- T! -J^ 3, .E -C ,2 S

I:SO T3 £ Z "

c

a.

%tu

Xc

w'E

>

1T3

>01

J :

IE2

' ^ , 5 5 ' — S ' ' > c

01 T: r r x; JH 42

o <— 01

S Q

s a i ^ ,1 ^ 5

"3 E

!UI

1

EDO

ra

roCo

lati

o>

Ec

0, J^ i — C-^ p -a ra c

.E 5

dj -g

3 ao DO c n,

E =

^ Era 3

B -^ i_

July 2007] Chickadee Song Admixture 931

10

8

6

4

2

0

Song type B{atricapillus playback)

0.5 1.0 1.5

Song type C

0.5 1.0 1.5

NX

oco3

O

8

6

4

2

0

10

8

6

4

2

0'

Song type E{carolinensis playback)

0.5 1.0 1.5

Song type W

0.5 1.0 1.5

8

6

4

2

0

1086420

Song type G

0.5 1.0 1,5

Song type X

0.5 1.0 1.5

Time (s)FTG. 2. Representative spectrograms of song types of atricapillus (B) and carolinensis (E) that were

used in playback, two additional carolinensis song types (C, G), and two atypical song types (W,X). Populations and locations (or source) of songs depicted are as follows: B = New York (Peterson1983), C = VA (Charles City County), E = Adams County, Ohio (Peterson 1983), G = WV4 (UpshurCounty), W = VA5 (Rappahannock County), X = MO4 (St. Clair County). Representations of othersongs not depicted are found as follows: D (Ward 1966, fig. 4 DNl-1), F (Ward 1966, fig. 5 VKl-1),H (Ward 1966, fig. 4 VN4-1), 1 (Ward 1966, fig. 5 FV5-3), Y (Sattler 1996, fig. 71; Ballard 1988, fig. 13A3), Z (Ward and Ward 1974, fig. 2 B).

al, 1999). Well-known amplitude modulation(Kroodsma et al. 1995, 1999) and frequencyshifts (Ratcliffe and Weisman 1985, Horn et al.1992) are commonly heard in most populations,but these are relatively minor variations on thebasic song, so we recognized only one atricapil-lus song type, B (Fig, 2).

Poecile carolinensis displays extensive indi-vidual and geographic variation in its song(Ward 1966). We recognized a total of seven caro-linensis song types (C-I) in our samples (Fig. 2).All but song type G have been reported in othercarolinensis populations distant from the range

interface with atricapillus (Ward 1966, Lohr 1995).Each possesses at least one descending intervalbetween a high note in the frequency range of5.9-7.4 kHz and a low note in the frequencyrange of 3.0-4,8 kHz. Lohr (1995) showed thatsuch a descending two-note interval in the fre-quency range appropriate for carolinensis is theminimal song characteristic necessary to elicit afull species-typical response in this species.

Occasional song variants deviating from oneof the common carolinensis song types occurredinterspersed in bouts of typical song. Thesevariants appeared to be formed by fhe addition

932 SATTLER, SAWAYA, AND BRAUN [Auk, Vol. 124

or deletion of one or more notes from the endof otherwise typical songs (Ward 1966, G. D.Sattler pers. obs.). We ignored these variantsongs unless they formed the predominant songof an individual. On the other hand, Robbins etal. (1986) included these variants as separatesong types (eight individuals), so in our re-analysis of their data we did likewise.

Four additional song types were encounteredthat were not easily attributable to either spe-cies. Two of these, Y and Z, were found onlyin populations at the range interface and havebeen reported previously from other portions ofthe range interface (Ward and Ward 1974, Tove1980, Ballard 1988, Sattler 1996). Two other songtypes, W and X (Fig. 2), have not been reportedpreviously for either species. Both were encoun-tered in carolinensis-like populations near therange interface. We refer to these four songtypes as atypical song types.

Quantitative analyses of whistled song.—Spectral analysis of songs was performed usingCANARY, version 1.1 (Bioacoustics ResearchProgram, Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology,Ithaca, New York). A 176-Hz filter bandwidthsetting was used in most cases to measuresong parameters, unless greater resolution wasneeded in measuring note duration, in whichcase a 1,4OO-H2 bandwidth setting was used.We measured eight variables in each song; theduration and onset, midpoint, and offset fre-quencies of both high and low notes. Mindfulof the charactenstics of carolinensis song demon-strated by Lohr (1995), we chose for analysis thehighest note of a song and the note following it,unless the highest note of the song was the lastnote (e.g., song type X; Fig. 2). In that case, weanalyzed the highest note and the one preced-ing it. This procedure was followed throughout,including our re-analysis of the Missouri tran-sect data of Robbins et al. (1986), Those authorsmeasured the same eight variables on the firsttwo notes of every song, regardless of pitch. Weavoided that procedure because it tends to pro-duce an artifactual appearance of intermediacyin the small percentage of carolinensis songs thatdo not begin with a high note followed by a lownote (e.g., song type E; Fig. 2).

Variation in song characteristics across theAppalachian contact zone was examined byperforming a principal component analysis(PCA) in SAS, version 8.2 (PROC PRINCOMP;SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina), on the

matrix of correlations among averages for theeight song variables. All 12 populations of thetwo Appalachian transects were included in theanalysis. Note duration was normally distributedin most cases, whereas note-frequency variableswere non-normally distributed in a number ofcases because of the presence of multiple songtypes in a population. Transformations failed tonormalize the frequency variables in these popu-lations, so untransformed values were retainedin the PCA. We also performed a PCA on theremeasured data of Robbins et al. (1986) fromMissouri, using the procedures described above.

Genetic analifsis.—After recording sessions,birds were collected with a shotgun and frozenon dry ice for transport to the lab for specimenpreparation and tissue extraction. Four diagnos-tic genetic markers were used to detect hybrid-ization and introgression (Fig. 3). One was theisozyme guanine deaminase (GDA) (Gill et al.1989, Sawaya 1990), for which electrophoresiswas carried out on liver tissue according toSattler and Braun (2000). The other three mark-ers were restriction-fragment-iength polymor-phism (RFLP) differences analyzed on Southernblots. DNA extraction and Southern analysis fol-lowed Sattler and Braun (2000). The three probesused to detect RFLPs were (1) a cloned fragmentof the chicken oncogene ski (Li et al. 1986), (2) arandomly cloned fragment of Tufted Titmouse(Baeolophus bicotor) DNA designated C7 (Sawaya1990), and (3) CsCl gradient-purified mitochon-dria! DNA (mtDNA) of P. carolinensis.

The four genetic markers have previouslybeen shown to be diagnostic for atricapillusand carolinensis (Mack et al. 1986, Gill et al.1989, Sawaya 1990, Sattler and Braun 2000).For example, population samples MO (20 atri-capillus from northern Missouri) and LA (21carolinensis from southern Louisiana) are fixedfor alternative alleles at each of the four markerloci (Sawaya 1990), as are samples PA (20 atrica-pillus from northern Pennsylvania) and VA (21carolinensis from southeastern Virginia; Sattlerand Braun 2000). Scoring of alternative allelesis straightforward and unambiguous; bandingpatterns for each locus are shown in Figure 3,

Because the parental populations do notshare alleles, hybrid ancestry can be inferred ifan individual is found to have any admixture ofatricapillus and carolinensis alleles among thesefour diagnostic markers. In other words, pureatricapillus must have only atricapilius alleles.

July 2007] Chickadee Song Admixture 933

B C B C C

16.2

8.8

5.3B C C

8.0

^ 6 . 2 V V 3.2

•

^ £. £B C C

1.7

• 1.2

f 2.6• 2.4

mtDNA C7 s/ci GDAFIG. 3. Banding pattems of alternative genotypes for tbe four genetic marker loci used. GDA is

an isozyme; mtDNA, C7, and ski are RFLPs (see text). B = atricapillus, C = carolinensis, B/C = hetero-zygote. Numbers beside DNA bands are molecular size estimates in kilobases. Cleavage patternsshown are produced by the restriction enzyme Pst 1 for mtDNA and C7, and by Eco Rl for ski. Inboth C7 and GDA panels, one lane has been removed to show the three genotypes juxtaposed.

and pure carolinensis must have only carolin-ensis alleles. Estimates of hybrid frequency areconservative because some later generation andbackcross hybrids may have parental genotypesby chance from reassortment among the fourmarkers. The frequency of female hybrids isespecially likely to be underestimated, becausetwo of the marker loci, GDA and C7, are sex-linked (Sattler and Braun 2000), and females arethe heterogametic sex. These two markers mayalso be physically linked on the Z chromosome,resulting in nonindependence and furtherincreasing the chance of misclassifying hybridsas parentals. Sattler and Braun (2000) gave allelefrequencies in each of the 12 Appalachian popu-lations for all four loci. Here, we classify birdsas hybrids or potential parentals on the basis oftheir genotypes (Table 1).

RESULTS

Levels of song adtnixture in Appalachian tran-sects.—We encountered chickadees that sangatricapillus and carolinensis songs syntopically

in population samples nearest the range inter-face on both the Virginia (VA2-VA4) and WestVirginia (WV3-WV4) transects (Fig. 4). Thesesame populations had the highest proportion ofhybrids determined genetically (Table 1 and Fig.4). Atypical song types Y and Z were found atthe Appalachian range interface (VA2 and WV3)but were uncommon in our samples (Table 2).Species-typical song types predominated atthe center of each transect, and tbese songsdid not sound abnormal or intermediate to ourears. Frequency and duration characteristics ofspecies-typical songs were maintained, even insympatry (Table 3). Variability in note durationand frequency within populations was greatestfor carotinensis (Table 3), where multiple songtypes were always present.

In a PCA of song bouts based on durationand frequency variables, there was little evi-dence of intermediacy in either Appalachiantransect. The first principal component (PCI)explained 68.2% of total variation (Table 4) andwas correlated positively with note frequencyand negatively with note duration. It exhibited

934 SATTLER, SAWAYA, AND BRAUN |Auk, Vol. 124

Virginia transect

(03O

O)co(A

o0)

I

VA1/WV1(15,0)

VA2(45.0)

VA4(28,6)

VA5(10,0)

West Virginia transect35-30-2S-20.15-

VA1/WV1{15.0)

WV2(15,0)

Missouri transect

BC

WV4(57,9)

WV5(47,4)

OH(40.0)

BC • '

Song classification

FIG. 4. Number of atricapillus (BC), carolinensis (CC), and atypical (?) song bouts heard or recordedin each population of the three transects. Numbers in parentheses indicate the percentage ofhybrids estimated genetically for each population. Ninety-three bouts heard in the field but nottaped are included.

a bimodal distribution in range interface popu-lations of each Appalachian transect (Fig. 5),separating atricapillus from carolinensis songbouts. In scatterplots of PCI versus PC2, onlya few song bouts from the Appalachian hybridpopulations fell between the ranges of the

parental samples from the same transect (Fig.6). The distinctions maintained between chick-adee songs at both sites on the Appalachianrange interface contrast with the extensivehybridization and intermediacy present in thesame populations, demonstrated by genetic

July 2007] Chickadee Song Admixture 935

TABLE 2. Number of singing birds in central populations of the three transects according to severalbroad repertoire categories. Only a subset of these songs was recorded and included in analysesfor intermediacy, and no individual is represented more than once.

Song type

atricapillus only (B)carolinensis only (C-I)atricapillus and atypicalcarolinensis and atypicalBilingualBilingual and atypicalBilingual-atypical subtotalTotal

VA2 and VA3

26242032

7 (12%)57

Popu]ation(s)

WV3

97

0190

10 (38%)26

VA+WV total

3531

21

122

17 (20%)83

MO3

10122051

8 (27%)30

(Table 1 and Fig. 5) and morphological analy-ses (Sattler and Braun 2000).

Some vocal admixture between Appalachianatricapillus and carolinensis was evident in thepresence of birds witb bilingual or atypicalsong repertoires near the range interface of eacbtransect. Such birds were especially common inthe We.st Virginia transect, where they made up38% of the birds heard singing in WV3, com-pared witb just 12% of the birds in VA2 and VA3combined (Table 2). The different frequency ofbilingual singing in the two Appalachian tran-sects was mirrored in the geographic extent ofsong sympatry as well. Both atricapillus and car-oline)tsis songs were common in an area >9 kmwide in WV3. By contrast, tbe area in wbichbotb atricapillus and carolinensis songs werecommon at tbe range interface between VA2and VA3 spanned only 4 km.

Levels of song admixture in the Missouri tran-sect.—The lack of song intermediacy in theAppalachian transects contrasts with tbe exten-sive intermediacy reported by Robbins et al.(1986) at the range interface in Missouri. In theircotitact-zone population (MO3), discriminantanalysis classified 37% of song bouts as interme-diate in duration and frequency characteristics.They also encountered atypical song types Yand Z and a moderate level of bilingual singing(27% of individuals; Table 2) spanning an area-9 km wide. Yet tbe Missouri transect had lowerlevels of hybridization and introgression deter-mined genetically (Table 1).

Re-analysis of tbe Missouri song data ofRobbins et al. (1986) by PCA according to oursong-type definitions confirmed the apparentdifference between Missouri and Appalachian

transects. Eigenvalues and factor loadingsfrom PCA were comparable to the analysis ofAppalachian populations (Table 4). In contrastto the bimodal distribution of PCI scores in tbeAppalachian transect interface populations,MO3 exhibited a unimodal distribution in PCIscores (Fig. 5). This contrast can be quantified byestimating the proportion of intermediate songsin each transect in scatterplots of the first twoPCA scores (Fig. 6). If songs falling hetween thelimits of reference parental populations of eachtransect are considered intermediate, 39.3% ofsongs in the central population of the Missouritransect (M03) exhibit intermediacy. This con-trasts with only 13.3% and 16.7% intermediatesongs in the central populations of the Virginia(VA2 and 3) and West Virginia (WV3) transects,respectively. Song type E bad a greater tendencytoward intermediacy in the PCAs than othersong types, but deleting it made little differencein the proportion of intermediate songs in anytransect (data not shown).

Correlation of song and genetics.—To assessthe relationship of song to genetic ancestry,we looked at the association between song, asmeasured by PCI scores, and genetic composi-tion, as measured by the number of atricapillusalleles per individual. Combining data from allthree transects at the population level, there wasa very strong correlation hetween a population'saverage PCI song score and its average geneticcomposition (Spearman's r^ = -0.91, one-tailedP < 0.01, « = 15). Tbis correlation is not sur-prising, however, because both variables arerelated to geographic position of populationsalong the transects. We can factor out tbe effectof geography by looking at the association

936 SATTLER, SAWAYA, AND BRAUN fAuk, Vol, 124

ro'c'5b

TO

•a5b

.s•c

BtoCO

CO

•J3to

EX

60CO

a.

CM

"o2

oZ

is I

i

-5 ^ ^

0 0I - H

o+1

I - H

CO

ro

I - H

CJ

+1

i ncO

CNI - H

o+1

( - H

roro

^ H

o+1

ro

f - H

CN

O+1oi nCO

COt N

o+1

CO

ro

roO+1

\0t N

ro

f - H

i no-H

i n

CO

o+!-,ro

ro

^ X

o o+i +1

^ CNin roCO r n

I N

O+1

[.^

ro

n jroO+1

t NX

CO

COI - H

o+1

1—,

O^

ro

OIT)

o•H

CNI - H

o o o d o c J o o+( +1 +1 +1 +1 +1 +i +1

oin

o o o o d d+1 +1 +1 +1 +1 -H

ro ro rn fO

•H

->

'—'I —

O

+1\n' T

•**f N

O

+1r H

r Nt N

o+1

i r t1'J

[ N

CN

O

+1ro

CN

o+1

r H

I N

t - H

• J '

o+1

o+1CT>i n

f—1

( N

O

+1

1—1

I - H

o+1

I - H

o+1

, - H

C l

O

+1

t oo+1

o+1

li iO+1

I N

rO to ro ro CO fO

I—"

o+1

o+1

.20

o+1

.06

" j '

o+1

.96

CO

o+1

.98

o+1

74

roc+1

CN

<N

o+1

rH rH

o o+1 +1^ oCO (N

o+1

05+1

98+1

94

o+1

37

i n

-H

70

o+1no

o+1nn

o+1

trt"

O

+1r H

o+t

O

+1ns•j^

COO

+1o

C N

o+1

1 '

o+1

CT>

[ N

o+1

i no+1

I N

CN

O

•H

'T111

X

o•H

I N

u )O

+1

( o r o c o c o ^ O ' . D i n ' . o

+1•t

o•H

0 0

o+1rNI N

O

+1f S^J^

o+1

o+1

o+1

,—1

i n

o+1

ro

O

o i

O41

O

O+1

o6

o•H

CN

O41

i n

o+1

O^

O

41

i n

+1 +1 +1 +1 +1 +1 +1 +1• ^ • ^ C O ' - ' O O O ' ^ O OO r O O — O ^ t N f O O ^

a in ro inN l D

+1 +1 +1 +1 +1 +(

*j] I'J^ CO

o o

^ o

roO

oo

roO

CTI

o

Xto

CO

r o

o

roO

?N

3 ro^ CO

+•1 41

^ B.

CO

41

0 0

i n

±0

o

o•H

O

mCO

±0

I N

ro

±0

r s j

CO ro r-j CO rsj ro

-o in a in X

'-I (N ro • * in< < < < < <> > > > > >

B •>

c -73 c :=

£"•?, £ in o01 S e .s

S- g " ^ 60^00 Q 3 § 3

Ul 'K 3 . 2 • -

^ 0

o E o = n

C P o o oj

* = - I £< u < (3 o

July 20071 Chickadee Song Admixture 937

TABLE 4. Correlations between song variables and principal component scores.

Character

NolelDurationOnset frequencyMidpoint frequencyOffset frequency

Note 2DurationOnset frequencyMidpoint frequencyOffset frequency

EigenvalueVariation explained

Virginia andWest Virginia

PCI

-0.650.950.940.92

-0.700.770.810,81

5.450.682

FC2

0.61-0.13-0.25-0.28

0.540.600.570.57

1.840.230

Missouri

PCI

-0.650.940.940.93

-0.500.800.840.84

5.350.669

PC2

0.70-0.11-0.20-0,20

0.700.550.510.50

1.880.235

between PCI scores and genetic makeup ofindividuals from the only two range interfacepopulations (WV3 and MO3) that had an appre-ciable mix of the songs and genes of both forms.There was a weakly significant correlation inWV3, and none in MO3 (Fig, 7). Many hybridindividuals in these populations (and others)sang accurate renditions of one or both species'song types, and a number of individuals geneti-cally pure for the four marker loci sang accuraterenditions of the other species' song (Fig. 7).Thus, the duration and frequency characteris-tics of song bouts were poor predictors of thegenetic ancestry of individual singers.

As an additional test, we examined theassociation between bilingual singing andhybridity in contact-zone populations of allthree transects (VA2, VA3, WV3, and MO3).To minimize potential bias, only individualscollected within 5 km of the estimated rangeinterface were included in the analysis. A higherproportion of bilingual birds were hybrids (10of 12, 83.3%) than nonbilingual birds (19 of 35,54.3%), but the association was not significant(Fisher's exact test, one-tailed, P = 0.072), againindicating that song type was a poor predictorof genetic ancestry.

DISCUSSION

Vocal admixture as an indicator of hi^bridization.—Song is an unreliable criterion for assessing lev-els of hybridization and introgression in thesechickadees. Although >50% of contact-zone

chickadees on both Appalachian transects weredetermined genetically to be hybrids, song inter-mediacy at these sites was minimal. Other formsof vocal admixture, such as bilingual or atypicalsinging, were also uncommon at the Virginiarange interface. Although bilingual and atypicalsinging was more common and occurred over abroader area in the West Virginia transect, thegeographicextent of any form of vocal admixtureon either transect was very narrow in relation togenetic mixing. Moreover, there was little or nocorrelation between an individual's PCI scorefor song and its genetic ancestry. Numerousindividuals with carolinensis-\\ke genotypes sang"normal" atricapillus songs, and vice versa.

Song has been found to be an equally unreli-able marker of hybridization in other songbirdhybrid zones (Ficken and Ficken 1967, Emlenet al. 1975, Sorjonen 1986). Also, song does notreflect paternal family lineages in many birds(Payne 1996, Payne and Payne 1997), In eachof these cases, the discordance between genesand song has been attributed to a strong com-ponent of learning in song ontogeny. Learningis important in the development of vocaliza-tions in all oscine songbirds studied, includingseveral members of the genera Pants and Poecile(Kroodsma and Baylis 1982, Ficken and Popp1995, Hughes et al. 1998), Most pertinently, atrica-pillus nestlings tutored with a tape of carolinensissong learned most elements of the heterospecificsong, whereas carolinensis nestlings developedsongs nearly identical to an atricapillus tutortape (Kroodsma et al. 1995). Therefore, caution

938 SATTI ER, SAWAYA, AND BRAUN IAuk,Vol. 124

Virginia transect West Virginia transect Missouri transect

1

-50 -25

PA(0)

25 SO •SO -25 25 SO

VA1/WV1(15.0)

•SD -25 0 25 SO

VA1/WV1(15.0)

-SO -25 25 SO

3•O

•>

.Eo0)

E3

VA2(45.0)

JUU-&0 -25 0 25 SO

VA3(62.5)

25 SO

VA4(28.6)

WV2(15.0)

6-15.4.3.2.1.0.-SO -25 0 25 SO

-SO -25 0 25 SO

M01&2(12.9)

M04(4.8)

25 5i) -&0 -25 25 5.0

VA5(10.0)

-so -2.5 0 25 SO

f] VW5(47.4)

3.2,

SI-so -25 0 25 5,0

-&0

VA(0)

25 SO

OH(40.0)

-so -25 0 25 SO

PCI

FIG. 5. Principal component 1 (PCI) scores of songs exhibited a bimodal distribution in the centerof the Virginia transect (VA2 and VA3) and West Virginia transect (WV3) but a unimodal distribu-tion in the center of the Missouri transect (MO3). Numbers in parentheses indicate the percentageof hybrids estimated genetically for each population. Tlie outlier in OH at -2.5 was a carolinensisE song type that appeared atricapillus-like on the basis of PCI but was well separated from all atri-capillus by its low PC2 score (Fig. 6).

July 2007] Chickadee Song Admixture 939

OQ.

parentalcarolinensis

(VA)

parentalatricapiltus

(PA)

VA2&3

• carolinansis song types

M Atypical song types

o atricapillus song types

-5 -4 -3 -2

o

54321

0

-1

-2

-3

-4

-5

parentalcarolinensis

(OH)

WV3

parentalatricapillus

(PA)

• carolinensis song types

X Atypical song types

o atricapillus song types

-5 - 4 -3 - 2 - 1 0 1

oD.

5

4

3

2

1

0

-1

-2

-3

-4

-5

parentalcarolinensis

(M04)

MO3

parentalatricapillus(M01&2)

• carolinensls song types

• Atypical song types

o atrtcapitlus song types

-5 -4 -3 -2

PC2

FIG. 6. There was a distinct separation between atricapillus and carolinensis song types in scatterplotsof the first two PCA scores of songs for central populations in the Virginia transect (VA2 and VA3) andWest Virginia transect (WV3), but not in the Missouri transect (MO3). Thirty-two Appalachian individ-uals that sang more than one song type are represented multiple times, as are seven individuals in M03that sang versions of a single song type differing in number of notes. Polygons enclose the positions ofreference samples from each transect (individual data points not shown).

940 SATTLER, SAWAYA, AND BRAUN [Auk, Vol. 124

WV3

(0

i)(0

• • •• •«

5.Rl'UO

ns

0)QE3

7n

6

5-

4-

32-

1-

0--1-u

7n

6-

5-

4-

3-

21-

0--1-

* * •

•:•

*o

\ -3 -2 -1

« * »•* <r

•

•

-3 -2 -1

•

O

••

0 O

0 1

M03

oD

• *

*

2 3 4 5

* *

0 1

PC1

O *#

2 3 4 5

FIG. 7. Scatterplots of song PCI scores ver-sus number of atricapillus alleles of the sing-ing individual show that, in the hybrid zone,song characteristics were poor predictors ofthe singer's genetic ancestry. Data are from thetwo range-interface populations where therewas an equal representation of atricapillus andcarolinensis song. When rank-transformed datawere tested by Spearman's rank correlation,there was a significant correlation in WV3(r = -O.40, one-tailed P = 0.014, n = 30) but notin MO3 (Spearman's r^ = -0.21, one-tailed P =0.098, n = 38). Each asterisk represents a birdthat sang a single song type. Open and closedsquares, circles, stars, and hexagons identifysong bouts of different song types sung by thesame individual.

must be exercised in drawing conclusions abouthybridization between atricapillus and carolinen-sis on the basis of vocalizations alone.

More broadly, finding a weak relationshipbetween levels of vocal admixture and levels ofgenetic intermediacy appears to be related moredirectly to the function of vocal communicationsystems and ecological interactions betweenthe two forms than to genetic ancestry. Socialadaptation of singing behavior to the localpopulation norms in which a bird attempts tofind a mate and hold a territory may decouplethe cultural transmission of song from paren-tal lineages (Payne 1996). Also, song learningallows individuals of some species to developrepertoires with shared song types that can bematched as a means of sending warning signalsto neighbors, improving competitive ability(Burt et al. 2001). Both processes may operatewithin this and other hybrid zones.

The distinctive vocal boundary between thesechickadees can be likened to that between song-type dialects within a species. Although dialectboundaries may he linked to reductions in geneflow (MacDougall-Shackleton and MacDougall-Shackleton 2001), they often are not (Soha et al.2004). In the chickadee case, the primary harrierto gene flow appears not to be an exogenoussocial factor such as vocal communication,but rather endogenous genetic ones (Bronsonet al. 2003a). The barrier appears to act morestringently on some genetic loci than on others(Sattler and Braun 2000, Bronson et al. 2005).

Geographic variation in vocal admixture.—Theclear multivariate discrimination of atricapillusand carolinensis songs at the range interface inAppalachia stands in contrast to the intermedi-acy found by Robbins et al. (1986) in Missouri.We substantiated this difference by a re-analysisof tbe earlier data in the same statistical frame-work used here. Vocal intermediacy at the rangeinterface in Missouri is reminiscent of vocalinteractions at a Siberian hybrid zone betweentwo subspecies of Great Tit (Parus major), whereboth intermediate songs and bilingual singingare found (Martens 1996), It differs from themore common situation where hybrids singthe songs of one or both species and interme-diate vocalizations are rare (Ficken and Ficken1967, Payne 1980, Morrison and Hardy 1983).However, intermediacy in the Missouri contactzone is subtle; most songs sounded more or lesstypical of one or the other parental species to the

July 20071 Chickadee Song Admixture 941

human ear (Robbins et al. 1986). Multivariateanalysis was required to detect intermediacy,and the presence of bilingual singers was themore obvious vocal indication that hybridiza-tion was taking place. The situation is thereforesimilar to that found with hybridizing PiedFlycatchers {Ficedula hypoleuca} and CollaredFlycatchers (F. rt/(j/co///s)"(GeIter 1987).

Differences in vocal admixture were alsonoted between our two Appalachian transects.Intermediate songs were rare in both, but theproportion of bilingual singers and the area ofsong sympatry were greater in West Virginiathan in Virginia, Similar variation is found in thecontact between Alpine and lowland forms ofWillow Tit (Poecile montanus), where vocal inter-mediacy is found in some areas but not in others(Thonen 1962, Martens and Nazarenko 1993),

Factors affecting occurrence and detection ofvocal admixture.—Three sampling issues couldaffect apparent levels of admixture. First, thefull repertoire of some birds was probablynot sampled in our relatively short recordingsessions, especially for carolinensis. This couldlead to a bias if certain song types are under-represented in our sample. Second, birds maymatch their songs to the playback tapes used.Horn et al. (1992) found that atricapillus fre-quency-matched their songs to playback tapesin a manner analogous to song matching usingmultiple song types (Krebs et al. 1981, Otter etal. 2002). Such behavior could produce a biasagainst detecting song intermediacy. Third,playback tapes clearly influenced recordedrepertoires in that presentation of the secondsong type sometimes stimulated birds to switchtypes and exhibit bilingual singing. Thus, ourestimates of the frequency of bilingual singingare undoubtedly higher than those that wouldbe obtained by listening passively to birds sing-ing spontaneously for the same amount of time.None of these potential biases could explainthe differences in admixture found in Missouri(Robbins et al. 1986) and the Appalachians(present study). The same playback tapes andrecording protocol were used in both studies.Ward and Ward (1974) also used playbacktapes at the contact zone in southeasternPennsylvania and found substantial numbersof bilingual and atypical singers.

Ecological factors are a plausible explanationfor geographic variation in vocal admixture. Atmost points along the atricapillus-carolinensis

contact zone, there is no appreciable change inelevation or other ecological transition associ-ated with the range interface. In Missouri,there is a moderate transition, because thecontact zone parallels the boundary betweenthe forested Ozark Plateau and the largelytreeless Great Plains (Robbins et al. 1986), InAppalachia, however, ecological variationassociated with elevation is much greater, andatricapillus is restricted to higher elevations inthis region. Chickadee dispersal may be inhib-ited by habitat preferences and sharp habitattransitions, or the fitness of either form may bereduced in the alternative habitat. In either case,both hybridization and social interaction may bemore restricted along the Appalachian transectsbecause of ecological segregation. Lower inter-mediacy in species characteristics in Appalachiais the expected outcome, and this effect may begreater for culturally transmitted vocal traitsthan for morphological or genetic ones.

Other factors may contribute to geographicvariation in vocal admixture. Suboptimal habi-tat or other conditions that depress populationdensities of chickadees at the contact zone in theMidwest (Robbins et al. 1986, Grubb et al, 1994)and in the Smoky Mountains (Tanner 1952, Tove1980) may produce a sharp vocal interface thatmasks significant levels of hybridization. If pop-ulation densities are low, there may be feweropportunities for vocal interactions among thetwo forms, yet the proportion of hybrid pair-ings might actually increase because of scarcityof mates. Also, temporal differences in the ageof contact may have allowed more or less vocaladmixture to accumulate in different regions.Finally, genetic differences between easternand western populations of carolinensis (Gill etal. 1989, 1999; Sawaya 1990; Sattler 1996) havethe potential to influence interactions betweenatricapilius and carolinensis at many levels.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to T. Parsons, P. Sattler, andM. Hayslett for field assistance; M. Steffan, K.Zeller, T. Parsons, D. Albright, J. Blake, T Glenn,C. Huddleston, D. Emery, and others associatedwith the Smithsonian Institution's Laboratory ofMolecular Systematics for technical assistance;and D, Dance, K. Winicer, G. Graves, E. Morton,M. Isler, P. Isler, X. Retnam, and D. Jennings forguidance in data analysis. J. P. Angle, C. Angle,

942 SATTI,ER, SAWAYA, ANI) B R A U N [Auk, Vol. 124

J. Dean, R. Clapp, and the Division of Birds,U.S. Museum of Natural History, providedlogistic support for field work and assisted inthe preparation and cataloguing of specimens.We thank R. Brumfield, T. Glenn, J. Hailman,D. Kroodsma, R. Payne, and three anonymousreviewers for helpful comments on earlier ver-sions of the manuscript. This research was sup-ported by a Smithsonian Institution PredoctoralFellowship (to G.D.S.), the Alexander WetmoreMemorial Fund of the American Ornithologists'Union, and the J. J. Murray Award of theVirginia Society of Ornithology.

LITERATURE CITED

BALLARD, K. W. 1988. An analysis of a contactzone between the chickadees Parus atricapil-lus and P. carotinensis in the mountains ofsouthwestern Virginia. M.S. thesis, GeorgeMason University, Fairfax, Virginia.

BRAUNING, D. W., ED, 1992. Atlas of BreedingBirds in Pennsylvania. University ofPittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

BREWER, R. 1963. Ecological and reproductiverelationships of Black-capped and Carolinachickadees. Auk 80:9-47.

BRONSON, C. L., T. C. GRUBB, JR., AND M. J.BRAUN. 2003a. A test of the endogenousand exogenous selection hypotheses for themaintenance of a narrow avian hybrid zone.Evolution 57:630-637.

BRONSON, C. L., T C. GRUBB, JR., G. D, SAriLtR,AND M. J. BRAUN, 2003b. Mate preference:A possible causal mechanism for a movinghybrid zone. Animal Behaviour 65:489-500.

BRONSON, C. L., T. C. GRUBB, JR., G. D. SATILER,AND M. J. BRAUN. 2005. Reproductive successacross the Black-capped Chickadee {Poecileatricapillus) and Carolina Chickadee {P.carolinetisis) hybrid zone in Ohio. Auk 122:759-772.

BUCKELEW, A. R., JR., AND G. A. HALI. 1994.The West Virginia Breeding Bird Atlas.University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh,Pennsylvania.

BURT, ]. M., S. E. CAMPBELL, AND M, D. BEECHER.2001. Song type matching as threat: Atest using interactive playback. AnimalBehaviour 62:1163-1170.

COOK, A. 1975. Changes in the Carrion/Hoodedcrow hybrid zone and tbe possible impor-tance of climate. Bird Study 22:165-168.

CURRY, R. L, 2005. Hybridization in chickadees;Much to learn from familiar birds. Auk 122:747-758.

DIXON, K. L., AND R. A. STEFANSKI. 1970. Anappraisal of the song of the Black-cappedChickadee. Wilson Bulletin 82:53-62.

EMLEN, S. T,, J. D. RISING, AND W. L. THOMPSON.1975, A behavioral and morphological studyof sympatry in the Indigo and Lazuli bun-tings of the Great Plains. Wilson Bulletin 87:145-179.

FICKEN, M. S., AND R. W. FICKEN. 1967. Singingbehaviour of Blue-winged and Golden-winged warblers and their hybrids.Behaviour 28:149-181.

FICKEN, M. S., R. W. FICKEN, AND S. R. WIIKIN.1978. Vocal repertoire of the Black-cappedChickadee, Auk 95:34-48.

FICKEN, M. S., AND J. POPP. 1995, Long-term per-sistence of a culturally transmitted vocaliza-tion of the Black-capped Chickadee, AnimalBehaviour 50:683-693.

GELTER, H, P, 1987, Song differences betweenthe Pied Flycatcher Ficedula hypoteuca, theCollared Flycatcher f, atbicollis, and theirhybrids. Ornis Scandinavica 18:205-215.

GILL, F. B. 1998, Hybridization in birds. Auk115:281-283.

GILL, F, B., D. H. FUNK, AND B. SILVERIN. 1989.Protein relationships among titmice {Parus).Wilson Bulletin 101:182-197.

GILL, F. B., A. M. MOSTROM, AND A. L. MACK.

1993. Speciation in North American chicka-dees: I. Patterns of mtDNA genetic diver-gence. Evolution 47:195-212.

GILL, F, B., B. SLIKAS, AND D. AGRO. 1999.

Speciation in North American chickadees:IL Geography of mtDNA haplotypes inPoecile carolinensis. Auk 116:274-277.

GRANT, P R., AND B. R. GRANT, 1992.

Hybridization of bird species. Science 256:193-197.

GRIEEITHS, R., M. C. DOUBLE, K. ORR, AND R. J. G.

DAWSON. 1998. A DNA test to sex most birds.Molecular Ecology 7:1071-1075.

GRUBB, T. C , JR., R. A. MAUCK, AND S. L. EARNST.1994. On no-chickadee zones in MidwesternNorth America: Evidence from the OhioBreeding Bird Atlas and the North AmericanBreeding Bird Survey. Auk 111:191-197.

HAILMAN, J. P. 1989. The organization of majorvocalizations in the Paridae. Wilson Bulletin101:305-343.

July 20071 Chickadee Song Admixture 943

HAILMAN, J. P., AND M. S. FICKEN. 1996. Compara-tive analysis of vocal repertoires, with refer-ence to chickadees. Pages 136-159 in Ecologyand Evolution of Acoustic Communication inBirds (D. E. Kroodsma and E. H. Miller, Eds.),Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York.

HORN, A. G., M. L. LEONARD, L. RATCLIFFE,S. A. SHACKLETON, AND R. G. WEISMAN.1992. Frequency variation in songs of Black-capped Chickadees {Parus atricapillus). Auk109:847-852.

HUGHES, M., S. NOWICKI, AND B. LOHR. 1998. Calllearning in Black-capped Chickadees {Parusatricapiiius): The role of experience in thedevelopment of 'chick-a-dee' calls. Ethology104:232-249.

JOHNSTON, D, W. 1971. Ecological aspects ofhybridizing chickadees {Parus) in Virginia.American Midland Naturalist 85:124-134.

KREBS, J. R., R. ASHCROFT, AND K. VAN ORSDOL.1981. Song matching in the Great Tit Parusmajor L. Animal Behaviour 29:918-923.

KROODSMA, D. E. 1982. Song repertoires:Problems in their definition and use. Pages125-146 in Acoustic Communication in Birds,vol. 2 (D. E. Kroodsma, E. H. Miller, and H.Ouellet, Eds,). Academic Press, New York.

KROODSMA, D. E,, D. J. ALBANO, P. W. HOULIHAN,AND J. W. WELLS. 1995. Song development byBlack-capped Chickadees {Parus atricapillus)and Carolina Chickadees {P. carolinensis).Auk 112:29-43.

KROODSMA, D. E., ANDJ.R.BAYLIS. 1982. Appendix:A world survey of evidence for vocal learn-ing in birds. Pages 311-337 in AcousticCommunication in Birds, vol, 2 (D. E.Kroodsma, E, H, Miller, and H. Ouelett,Eds.). Academic Press, New York.

KROODSMA, D. E., B. E. BYERS, S. L. HALKIN, C.HILL, D. MINIS, J. R. BOLSINCER, J. DAWSON,E. DoNELAN, J. FARRINGTON, F. B. GILL, ANDOTHERS, 1999. Geographic variation in Black-capped Chickadee songs and singing behav-ior. Auk 116:387-^02.

Ll, Y., C. M. TuRECK, J. K. TEUMER, AND E.STAVNEZER, 1986. Unique sequence, ski, inSloan-Kettering avian retro viruses withproperties of a new cell-derived oncogene.Journal of Virology 57:1065-1072.

LOHR, B, 1995. The production and recogni-tion of acoustic frequency cues in chicka-dees. Ph.D. dissertation. Duke University,Durham, North Carolina.

MACDOUGALL-SHACKLETON, E. A., AND S, A.MACDOUGALL-SHACKLETON. 2001, Culturaland genetic evolution in Mountain White-crowned Sparrows: Song dialects are asso-ciated with population structure. Evolution55:2568-2575.

MACK, A. L., F. B. GILL, R. COLBURN, AND C.SPOLSKY. 1986. Mitochondrial DNA: A sourceof genetic markers for studies of similar pas-serine bird species. Auk 103:676-681.

MARTENS, J. 1996, Vocalizations and speciationof Palearctic birds. Pages 221-240 in Ecologyand Evolution of Acoustic Communicationin Birds (D, E. Kroodsma and E. H. Miller,Eds.). Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NewYork.

MARTENS, J., AND A. A. NAZARENKO. 1993.Microevolution of eastern Palaearctic GreyTits as indicated by their vocalizations {Parus[P{)(Y-/7t'|: Paridae, Aves), 1. Parus montanus.Zeitschrift fur Zoologische Systematik undHvolutionsforschung 31:127-143.

MERRITT, P G. 1978. Characteristics of Black-capped and Carolina chickadees at therange interface in northern Indiana. Jack-Pine Warbler 56:171-179.

MERRITT, P. G. 1981. Narrowly disjunct allopatrybetween Black-capped and Carolina chicka-dees in northern Indiana. Wilson Bulletin93:54-66.

MORRISON, M. L., AND J. W. HARDY. 1983.Hybridization between Hermit andTownsend's warblers. Murrelet 64:65-72.

MOSTROM, A. M., R. L. CURRY, AND B. LOHR.2002. Carolina Chickadee {Poecile carolinen-sis). In The Birds of North America, no. 636(A. Poole and F. Gill, Eds.), Birds of NorthAmerica, Philadelphia,

NowicKi, S., J. Ponos, AND F. VALDES. 1994.Temporal patterning of within-song typeand between-song type variation in songrepertoires. Behavioral Ecology andSodobiotogy 34:329-335.

O'lTER, K. A., L. RATCLIFFE, M. NJEGOVAN, ANDJ. FoTHERiNGHAM. 2002. Importance of fre-quency and temporal song matching inBlack-capped Chickadees: Evidence frominteractive playback. Ethology 108:181-191.

PATERSON, H. E. H. 1985. The recognition con-cept of species. Pages 21-29 in Speciesand Speciation (E. S. Vrba, Ed.). TransvaalMuseum Monograph, no. 4, Pretoria, SouthAfrica.

944 SATFLER, SAWAYA, AND BRAUN [Auk, Vol. 124

PAYNE, R. B. 1980. Behavior and songs of hybridparasitic finches. Auk 97:118-134.

PAYNE, R. B. 1981. Song learning and socialinteractions in Indigo Buntings. AnimalBehaviour 29:688-697.

PAYNE, R. B. 1996. Song traditions in IndigoBuntings: Origin, improvization, disper-sal, and extinction in cultural evolution.Pages 198-220 in Ecology and Evolutionof Acoustic Communication in Birds (D. E.Kroodsma and E. H. Miller, Eds.), CornellUniversity Press, Ithaca, New York.

PAYNE, R. B., AND L. L. PAYNE. 1997. Field obser-vations, experimental design, and the timeand place of learning bird song. Pages 57-84in Social Influences on Vocal Development(C. T. Snowden and M. Hausberger, Eds.).Cambridge University Press, New York.

PETERJOHN, B. G. 1989. The Birds of Ohio.Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

PETERSON, R. T. 1983. The Peterson Field GuideSeries: A Field Guide to Bird Songs ofEastern and Central North America, 2nded. Laboratory of Ornithology, CornellUniversity, Ithaca, New York,

RATCLIFFE, L. M., AND R. G. WEISMAN. 1985.Frequency shift in the fee bee song of theBlack-capped Chickadee. Condor 87:555-556.

RISING, J. D. 1968. A multivariate assessment ofinterbreeding between the chickadees Parusatricapillus and P. carolinensis. SystematicZoology 17:160-169,

RISING, J. D. 1983. The Great Plains hybrid zones.Pages 131-157 m Current Ornithology, vol. 1(R. F. Johnston, Ed.). Plenum Press, NewYork.

ROBBINS, M, B., M, J. BRAUN, AND E. A. TOBEY.1986. Morphological and vocal variationacross a contact zone between the chicka-dees Parus atricapilius and P. carolinensis.Auk 103:655-666,

SATTLER, E. D. 1996, The dynamics of vocal,morpbological, and molecular interactionbetween hybridizing Black-capped andCarolina chickadees. Ph.D. dissertation.University of Maryland, College Park.

SATTLER, G. D., AND M. J. BRAUN. 2000.Morphometric variation as an indicator ofgenetic interactions between Black-cappedand Carolina chickadees at a contact zonein the Appalachian Mountains. Auk 117:427-^44.

SAWAYA, P. L. 1990. A detailed analysis of thegenetic interaction at a hybrid zone betweenthe chickadees Parus atricapillus and P.carolinensis as revealed by nuclear and mito-chondrial DNA restriction fragment lengthvariation. Ph.D. dissertation. University ofCincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio,

SMITH, S. T. 1972. Communication and othersocial behavior in Parus carolinensis.Publications of the Nuttall OrnithologicalClub, no. 11.

SOHA, J. A., D. A. NELSON, AND P. G. PARKER. 2004.Genetic analysis of song dialect populationsin Puget Sound White-crowned Sparrows.Behavioral Ecology 15:636-646.

SORJONEN, J. 1986. Mixed singing and inter-specific territoriality — Consequences ofsecondary contact of two ecologically andmorphologically similar nightingale spe-cies in Europe, Ornis Scandinavica 17:53-67.

TANNER, J. T. 1952. Black-capped and Carolinachickadees in the southern AppalachianMountains. Auk 69:407- 424.

THONEN, W. 1962. Stimmgeographische,okologische, und verbreitungsgeschichtliche Studien iiber d ie Monchsmeise{Parus montanus Conrad), OrnithologischeBeobach ter 59:101-172.

TOVE, M. H. 1980. Taxonomic and distributionalrelationships of Black-capped {Parus atrica-pillus) and Carolina {P. carolinensis) chicka-dees in the southern Blue Ridge Province,North Carolina. M.S. thesis. WesternCarolina University, Cullowhee, NorthCarolina.

VIRGINIA DEPARTMENT OF GAME AND INLANDFISHERIES-VIRGINIA SOCIETY OF ORNITHOLOGY.1989, The breeding bird atlas project hand-book and data, 1984-1989. (VSO AtlasCommittee, Eds.). Virginia Department ofGame and Inland Fisheries, Richmond.

WARD, R. 1966. Regional variation in the songof the Carolina Chickadee. Living Bird 5:127-150.

WARD, R., AND D. A. WARD. 1974. Songs incontiguous populations of Black-cappedand Carolina chickadees in Pennsylvania.Wilson Bulletin 86:344-356.

Associate Editor: K. Yasukawa