American Woodcock – Final Paper- 1 - Running Head...

Transcript of American Woodcock – Final Paper- 1 - Running Head...

American Woodcock – Final Paper- 1 -

Running Head: AMERICAN WOODCOCK – FINAL PAPER

American Woodcock: Final Paper

Eric Miller

Green Mountain College

© 2009 H. Eric Miller

American Woodcock – Final Paper- 2 -

Species Background The Pennsylvania Game Commission lists numerous birds that comprise a list of species of

conservation concern. Birds such as willow flycatcher (Empidonax traillii), alder flycatcher

(Empidonax alnorum), brown thrasher (Toxostoma rufum) and American woodcock (Scolopax

minor) appear on the list due to their special moist, shrub-scrub habitat requirements. The need for

specialized habitat which is in decline across most of Pennsylvania (PA) has brought much needed

attention to woodcock in this state (Palmer 2008). American woodcock are ground nesters and

nesting locations are often chosen in young second growth forests (Mendall and Aldous 1943,

Sheldon 1967). Male woodcock typically arrive in PA in late February through early March and the

females follow (Liscinsky 1972). Breeding begins upon arrival and usually concludes by late May

with females nesting within 90 meters of an occupied singing ground (Sepik et al. 1981).

Little is known about woodcock populations prior to European colonization however Sheldon (1967)

suggests that records may go back as far as 200 years and do concur with modern day woodcock

population locales. In 1783, The Sportsman’s Companion ran an article on woodcock hunting

methods of the late 18th century (Palmer 2008). Sheldon (1967) was also able to locate records from

Civil War era market hunters who reported a large quantity of birds “unknown to modern hunters”.

Woodcock had little protection until the Lacey Act of 1900 which outlawed interstate shipment of

illegally killed game (Palmer 2008). In 1918, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act positioned woodcock

hunting under federal regulation and ended market hunting (Palmer 2008).

According to Palmer (2008), woodcock are currently recognized as a priority species in numerous

management plans including the Pennsylvania Wildlife Action Plan (2008) and the U.S. Shorebird

Conservation Plan (Brown et al. 2001). Additionally, the Nature Conservancy and the National

American Woodcock – Final Paper- 3 -

Figure 1. Woodcock management regions, breeding range, and Singing-Ground Survey (SGS) coverage (Straw et al. 1994)

Audubon Society have identified woodcock as a crucial species of management concern because it is

an important species to the public. Hunters enjoy pursuing them with dogs as they offer great table

fare and non-hunters are awed each spring by the courtship displays of males. Due to its migratory

status, woodcock fall under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) which

manages woodcock according to two regions, the Eastern and Central (Fig.1) (Palmer 2008). From

1968 to present, the woodcock population has declined considerably in both regions. Early

successional forest habitat loss and degradation are considered to be the prime factors causing this

decline (Palmer 2008). Hunting has not proven to be additive to woodcock mortality (McAuley et

al. 2005) under USFWS season and bag limit guidelines. The federal guideline is 25 to 45 hunting

days per year and a 5 bird / day bag limit with states being able to set their season anywhere within

those guidelines. Pennsylvania offers a 25 day season with a 3 bird per day bag limit.

American Woodcock – Final Paper- 4 -

American woodcock are habitat specialists, preferring early successional forest stages (Palmer

2008). The loss of this habitat is one of the major causes of a negative population growth.

Woodcock regularly seek scrub/shrub or seedling/sapling habitat, comprised of dense cover. Vacant,

reverting farm land and young hardwood stands provide the majority of PA woodcock habitat

(Palmer 2008). In PA, much of the available habitat is scattered throughout the state. This range of

early successional forest habitats on proper soils provides the habitat needs of breeding, migrating

and wintering woodcock. It is the quality and availability of these habitats that determine population

densities (Palmer 2008). Research has indicated that creating early successional forest habitat on

suitable soils is beneficial in increasing populations of woodcock (Dwyer et al., 1983). Clearly,

habitat loss and degradation negatively influence woodcock populations and stopping this must be a

major priority if the population decline is to reverse.

The biggest cause of habitat loss is development. Large losses of early successional habitat took

place from the 1950’s through 1970’s (Haynes et al. 1988) and because of this woodcock breeding

populations have since been in a long-term decline (Kelley et al. 2007). PA’s resident breeding

woodcock population has followed the 3.4% per year decline of the overall population (Palmer

2008). Additionally, land use practices are responsible for the decline in early successional habitat.

Farms that once were allowed to naturally revert are now being turned into houses and shopping

malls. Interestingly, Sauer et al. (2005) found that most mature forest bird species have increasing

population trends, while approximately half of all early successional habitat specialists are declining.

Consequently, the American Bird Conservancy lists early successional habitats in eastern deciduous

forests as one of the most threatened habitats (Palmer 2008).

American Woodcock – Final Paper- 5 -

Habitat degradation is another factor in woodcock population declines. Degradation is defined as

the point at which some or all of these resource needs are no longer being met (Groom et al. 2006).

Woodcock use different habitats at different times of the day and year (Liscinsky 1972, W.J. Palmer

personal communication 2008). For instance, males use small forest openings at dawn and dusk in

the spring to attract mates. Nesting, feeding, resting and brood rearing cover typically occur near an

occupied singing ground (D.G.McAuley personal communication). The loss of one part reduces the

overall ability of the habitat to meet the needs of woodcock. Should one of these pieces be

removed, the likelihood of use by woodcock decreases substantially (Mendall and Aldous 1943).

Risk Factors Because woodcock are so closely tied to their habitat, they tend to use special components at

different times of the day and year (Palmer 2008). These components that should be considered for

woodcock conservation purposes are singing grounds, nesting and brood rearing cover, diurnal

cover, nocturnal cover and migratory cover (Palmer 2008). The loss of just one of these habitat

components can cause use by woodcock to decrease significantly (Mendall and Aldous 1943).

Faced with a historic population decline, it is vital that all aspects of woodcock habitat be managed

wisely if the overall negative population trend is to cease.

Singing Grounds

Woodcock courtship typically begins in March in Pennsylvania (PA) when birds return from

wintering in the southern United States. Males display for females in openings called singing

grounds. Natural openings like beaver meadows and man-made clearings like forest clearcuts,

reverting farmlands, roads, pastures, and cultivated fields all are utilized as singing grounds (Palmer

American Woodcock – Final Paper- 6 -

2008). Although size of singing grounds varies widely, no preference for any particular size opening

has been found (Mendall and Aldous 1943). In PA, openings vary from 0.1-13.9 acres, with higher

frequency of use on shrub sites (Gutzwiller and Wakely 1982). Occupied singing grounds are often

less than 100 m from diurnal cover (Straw et al. 1994).

Nesting and Brood Rearing Habitat

Females nest in a broad mixture of cover types and sites but prefer young, open second growth

hardwood stands (Liscinsky 1972). Nests are often located within 150 m of a singing ground and

broods are not moved from the nesting area (Palmer 2008). Low numbers of older, mature trees and

high stem densities of woody saplings or shrubs located on soil with an ample supply of earthworms

comprise quality brood rearing habitat (Dessecker and McAuley 2001). According to Liscinsky,

woodcock in PA have a fairly long nesting season (1972). He observed hatching between April 5 to

June 14, with the peak taking place at the end of April (1972). Furthermore, Liscinsky found that

incubation takes between 19 and 22 days (1972).

Diurnal Habitat

Thick stands of early successional forest, such as young hardwood trees or shrubs, on soils with

good quantities of earthworms are regularly used as diurnal cover (Hudgins et al. 1985). Diurnal

habitat requirements are rather generalized and suitable plant species composition varies broadly

(Palmer 2008). Even though an extensive assortment of plant species is utilized by woodcock,

several species-groups are important indicators of potential habitat (Palmer 2008). Stands of

hawthorne (Crataegus spp.), alder (Alnus spp.), aspen (Populus spp.), and dogwood (Cornus spp.)

frequently indicate the presence of quality woodcock habitat (Straw et al. 1994).

American Woodcock – Final Paper- 7 -

Nocturnal Habitat

From June through August or early September, most birds begin to move to nocturnal roosts at dusk

and return to their diurnal cover at dawn (Straw et al. 1994). A roost is frequently a field or other

opening like a singing ground however woodcock have been recorded roosting in diurnal cover (W.

L. Palmer, personal communication). According to Palmer (2008), use of openings versus forested

sites as roosting areas varies by age and sex.

Migratory Habitat

Very little research has been conducted on the habitat requirements of woodcock during migrations

(Palmer 2008) however migrating birds may use areas not inhabited by residents (Liscinsky 1972).

While ample breeding habitat for woodcock is often the focus, high quality habitats are also critical

for migrating birds. Areas for woodcock to stop and rest are very important for surviving the rigors

of migration (Palmer 2008).

Because a large quantity of research has been conducted on woodcock and their habitat

requirements, biologists and managers are able to confidently manage woodcock throughout their

range. However, even armed with this data, management is not that simple. In the next section, I’ll

address the general management practices and the population indices that drive them.

Management Overview In 2008, an American Woodcock Conservation Plan was designed at the federal level through a

partnership between the Woodcock Task Force, Migratory Shore and Upland Game Bird Working

Group, and the Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies (Kelley et al 2008). The main focus of

American Woodcock – Final Paper- 8 -

the national plan is to return woodcock populations to the levels present during the early 1970’s

(Kelley et al 2008). Population trends are examined by conducting singing-ground surveys (SGS) at

the state level in the central and northern portions of woodcock breeding range. The SGS were

designed to take advantage of the courtship display of the male woodcock (Kelley et al. 2008).

Studies by Mendall and Aldous (1943) and Goudy (1960) revealed that counting singing males

provided an index of woodcock populations and could be utilized to record population trends. It is

suggested that, based on calculated population density deficits, there are 986,000 fewer singing

males currently then there were almost forty years ago (Kelley et al 2008). This national plan calls

for the establishment approximately 21 million acres of woodcock habitat in order to reduce the

aforementioned population deficit and return population levels to that of the early 1970’s while

providing sufficient opportunity to enjoy the woodcock resource (Kelley et al. 2008). To better

understand woodcock population modeling, I want to look at little deeper at how these figures were

reached.

Figure 2. Bird Conservation Regions in PA (USFWS 2000).

American Woodcock – Final Paper- 9 -

A deficit approach was used to obtain population and habitat goals. Average woodcock populations

(singing males only) were estimated for the periods 1970-75 and 2000-2004 for each Bird

Conservation Region (BCR) (Palmer 2008). Initially, the number of singing males for the 1970-75

and 2000-04 survey periods was determined. Estimates from singing males per SGS route were then

converted to singing males per acre because the acreage covered per route was easily determined.

The total number of singing males in each county was then determined by multiplying the density

estimate by the total land base acreage in the county (Palmer 2008). It should be noted that this is not

only the available woodcock habitat acreage, but rather the entire county. The population estimate

for the state was determined by adding the population estimates from the three individual BCR

sections of the state, BCR 13, BCR 28 and BCR 29 (Fig. 2). The effective density of singing males

in each time period was determined by dividing the number of singing males by the number of acres

that could be managed for woodcock in all BCRs during that time period. The woodcock density

deficit was obtained by subtracting the current effective density from the historic effective density

(Palmer 2008). It is now possible to determine the number of singing males needed to be added to

reach the effective density observed during the 1970-75 survey period (Palmer 2008). To calculate

the population deficit, biologists multiplied the density deficit by the current number of manageable

acres in PA. These totals were then added together and revealed that PA has lost 40,098 singing

male woodcock since the early 1970s (Palmer 2008). Biologists then adjusted for available and

manageable habitat acreage, which depicted a population density deficit of 40,903 males. This

population density deficit was used to determine breeding habitat objectives and to return woodcock

densities to previous levels (Palmer 2008).

American Woodcock – Final Paper- 10 -

At the state level, woodcock in Pennsylvania are the responsibility of the Pennsylvania Game

Commission (PGC) which manages woodcock in 22 wildlife management units (WMU) across the

Commonwealth. In 2008, the PGC issued a state Woodcock Management Plan which is a

modification of the national conservation plan. The goals echo that of the federal plan; to reduce the

population deficit and increase the quantity of necessary early successional habitat. More

specifically, the goal is to return woodcock populations to densities that offer enhanced hunting and

viewing opportunities by increasing the number of breeding males by 27,000 and available habitat to

783,000 acres across PA by 2017 (Palmer 2008). Similar to the national hunting trend, hunting

woodcock in PA is compensatory even though the state ranked first in harvested birds in the eastern

region and fifth nationally (Palmer 2008). All of the above information provides a solid background

into the science and management of American woodcock but does it truly suggest that the goals of

management plan are obtainable? How well does the current management match up with ideal

woodcock management?

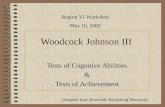

Figure 3. Key habitat components required by woodcock (Palmer 2008).

American Woodcock – Final Paper- 11 -

Ideal Management Due to the large amount of attention that woodcock have been receiving recently, much has been

discussed about the best way to stop the historic population decline. Most of the prominent

biologists in North America helped draft the national conservation plan. There is overwhelming

evidence that points to habitat as the key to obtaining the goal of increasing the PA singing male

population by 40,903 males and returning population densities to that of the early 1970’s. We know

that woodcock use of the specialized habitat components is dependent on multiple factors like time

of day and year (Fig. 3 Palmer 2008). Furthermore, the loss of one of these habitat components can

cause use by woodcock to decrease significantly (Mendall and Aldous 1943). Faced with a historic

population decline, it is vital that all aspects of woodcock habitat be managed wisely if the negative

population trend is to cease. After considering all aspects of management, it is quite clear that two

primary goals are needed to sustain and increase the population. An increase in the number of

singing males found during SGS and available early successional habitat will go a very long way to

ensure a viable woodcock population across North America. While these ideas seem genuine, are

they truly obtainable under real world limitations? For the most part, I am optimistic, however also

being a realist, I understand that not all goals are reachable

Analysis So far, I have provided scientific background on American woodcock as well as an overview of

management. This management is done in a trickle down fashion where USFWS and partners

initiated a national woodcock conservation plan. From there each state alters the plan for

implementation according to state BCRs. This is a tremendous first step. The ability to bring most

of the prominent woodcock biologists together to devise a plan and then allow them to disseminate

American Woodcock – Final Paper- 12 -

the plan at the state level and address each BCR is perfectly logical. It is the state agencies that

interact with the stakeholders, on the most part. However in this case, even the state agency is

considered a stakeholder.

Stakeholders

With little doubt, the major stakeholders in PA woodcock management can be divided into four main

groups; the sportsmen and women, development companies, forest products landowners, and the PA

Game Commission. I will be analyzing each of these groups in details based on their motivation

towards woodcock management.

Sportsmen and Women

This group has probably the most invested in woodcock management due their requirement to

purchase a hunting license and migratory game bird stamp to legally pursue woodcock in PA. I feel

that before going any further, it should be clarified that woodcock hunters, as a fraternity, are more

concerned with the well-being of the species than placing a bird in the game pouch. Within only

13,000 woodcock hunters in PA (Boyd and Cegelski 2008), very little direct income is pointed

towards woodcock. Conversely, 4 million dollars each year is set aside for pheasant propagation and

stocking (Klinger 2008). I must refrain from going much further, but I will offer that I feel native

species are taking a back seat just to appease 90,000 pheasant hunters. A bird native to China is

getting more funding than PA’s state bird, ruffed grouse (Bonasa umbellus), and American

woodcock combined. I’ll leave it at that, but I’m sure my sentiments are clear. This is the fine line

between scientist and advocate that was discussed during our lecture. Should a scientist be an

advocate? I feel that scientists should make public the information and allow advocacy groups to

take it from there. This happening is happening in PA. I, along with two other biologists, presented

these facts to the only organization dedicated to the betterment of American woodcock; Woodcock

American Woodcock – Final Paper- 13 -

Limited of PA (WLPA). This organization is dedicated to promoting woodcock management and

public knowledge of habitat needs and is leading the charge to increase funding and awareness of the

plight of American woodcock in PA (WLPA 2008).

To get back on track, even with the financial shortcoming, the woodcock being listed as a species of

special management concern is very helpful. Not in the sense that some look to capitalize on the

decline but rather that a wonderful amount of attention has been given to this species and the

sportsmen and women are leading the charge. It is my opinion, based on interaction with numerous

fellow woodcock hunters, that conserving habitat is the highest motivation for hunters. Hunters

realize just how important habitat is to the species and have a genuine desire to stop the historic

population decline.

PA Game Commission

The PGC is considered a stakeholder because they are legally mandated to manage all birds and

mammals with the Commonwealth of PA according to Section 322.A of title 34 (PGC 1996). It is

the PGC that took part in the development of the National Woodcock Conservation Plan and PA

Woodcock Management plan. Furthermore, the PGC sets the hunting seasons and bag limits

according to USFWS guidelines.

The motivation of the PGC is very evident. They are responsible to see that woodcock are managed

wisely and are under no threat of extinction. They have two items to consider when setting seasons

under the USFWS guidelines. The first is to provide an adequate opportunity for sportsmen and

women to pursue woodcock. A recent survey conducted by the Ruffed Grouse Society (RGS)

showed that 61 per cent of sportsmen and women felt that the season length was sufficient, while 21

American Woodcock – Final Paper- 14 -

per cent had no opinion (RGS 2008). It is safe to suggest that the PGC is meeting their mandate to

provide recreational opportunities to sportsmen and women.

The second consideration towards woodcock is species population status. In order to meet the

mandate, PGC must manage birds at a sustainable level. Maximum sustained yield is defined as the

greatest rate at which individuals may be harvested from a population without reducing the size of

the population (Ricklefs and Miller 2000). In order to perform this duty, PGC needs to constantly

monitor harvests and hunting pressure. In PA, woodcock hunter participation has remained steady

of the past five years (Boyd and Cegelski 2008) and the species population has stabilized over the

past three years (M. A. Banker personal communication). This can be interpreted to mean that

current woodcock management in PA is being performed properly. However, this does not mean

that management should continue as is. The main goal of the PA woodcock plan is to return

population densities to that of the 1970’s and in order to do so, habitat needs to be created and

maintained.

Forest Products Landowners

If PGC is to be considered the key aspect in maintaining a sustainable woodcock population, then

private landowners should be considered the key element in increased woodcock population

densities. The vast majority of PA’s forests are privately owned. The Commonwealth of PA owns

approximately 29 per cent while private land owners own 71 per cent (McWilliams et al. 2007).

Taking this into deliberation, it is apparent that the private landowner ultimately controls the ability

of the PA woodcock plan be properly implemented. According the McWilliams et al. (2007), PA’s

forests are stable at 16.6 million acres and comprise 58 per cent of the land base. While this is

exceptional news, the stage of the forest is cause for concern (Figure 4). Since woodcock depend on

American Woodcock – Final Paper- 15 -

early successional habitat, it is imperative that the private landowner be informed and involved in

maintaining a balance between sawtimber and seedling-sapling forest stages. Large landowners are

starting to become more involved and habitat management on private lands is increasing. I

personally just surveyed a 22,000 acres (8,903 ha) privately held tract in northcentral PA for

woodcock activity and use. The tract is owned by Headwaters Initiative Corporation and is one of

many large tracts in PA that are effectively cooperating with PGC to implement the woodcock plan.

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

1955 1965 1978 1989 2003PROPORTION OF FOREST

YEAR

FOREST SIZE CLASS TRENDS PENNSYLVANIA

SEEDLING-SAPLINGSAWTIMBER

Figure 4. Trends in proportions of forested lands in PA by size class, 1965-2003 (McWilliams et al. 2004).

Development Companies

PA lost 660,000 acres between 1989 and 2004 to development (McWilliams et al. 2007) and that

trend continues to today. It is perhaps the single most important factor pointing to the historical

woodcock population decline. This makes the development businesses, in general, a stakeholder in

woodcock management. Not because of the woodcock itself, but rather endangered and threatened

species that share early successional habitat. In my bioregion, the bog turtle (Clemmys

American Woodcock – Final Paper- 16 -

muhlenbergii) is the species stopping most development. This benefits woodcock due to the

woodcock’s preference for marshy-type habitats. This positions development companies as indirect

stakeholders. I say this because the legal hoops they must go through in order to survey bog turtle

habitat also work towards the advantage of woodcock.

Having considered all of the above information and also being involved with surveying woodcock

use on land under consideration for plan implementation, I can not help but feel excited and

optimistic towards woodcock management in PA. If we continue to gain support from private and

public landowners, this PA woodcock management plan can work. We can increase woodcock

populations because we still have 16.6 million acres of forest (McWilliams et al. 2007), but the

forest stage is uneven. Balancing the saw timber with the seedling-sapling stage will do wonders for

the state of woodcock in PA.

Conservation Steps The conservation of American woodcock must address two aspects; population management and

habitat management. Both are of equal importance, however without proper habitat, the woodcock

will continue to decline.

I. Continue to monitor species population trends.

a. Wing-survey. b. Hunter harvest surveys. c. Population response to habitat work.

II. Increase the ratio of early successional habitat to saw timber stage. a. Current mature stands are more available than young stages (see fig. 4).

III. Create areas throughout the Commonwealth to demonstration proper woodcock habitat management. a. Area 1 is already completed at Bald Eagle State Park near State College, PA. b. I am currently working with PGC and Wildlife Management Institute (WMI) to

initiate a demo area at Swatara State Park near Pine Grove, PA. IV. Educate public on importance of woodcock habitat to other species of conservation concern.

American Woodcock – Final Paper- 17 -

V. Implement state or national woodcock stamp where monies from stamp would be channeled directly towards woodcock habitat creation.

Literature Cited Boyd, R. and M. Cegelski 2008. 2007-08 Small Game and Furbearer Harvests. Pennsylvania Game

Commission. Harrisburg, PA, US.A.

Brown, S., S. Hickey, B. Harrington, and R. Gill. editors. 2001. United States Shorebird

Conservation Plan. Manomet, MA, USA.

Dessecker, D. R., and D. G. McAuley. 2001. Importance of early successional habitat to ruffed

grouse and American woodcock. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 29:456-465.

Dwyer, T. J., D. G. McAuley, and E. L. Derleth. 1983. Woodcock singing-ground counts and habitat

changes in the northeastern United States. Journal of Wildlife Management. 47:772-779.

Goudy, W. H. 1960. Factors affecting woodcock spring population indices in southern Michigan.

Thesis, Michigan State University, East Lansing, USA.

Groom, M.J., G.K. Meffe, and C.K. Carroll. 2006. Principles of Conservation Biology, 3rd Edition.

Sinauer Associates, Inc. Sunderland Massachusetts, USA.

Gutzwiller, K.J., and J. S. Wakely. 1982. Differential use of woodcock singing grounds in relation to

habitat characteristics. Pages 51-54 in T. J. Dwyer and G. L. Storm, technical coordinators.

Woodcock ecology and management. USFWS, Wildlife Research Report 14.

Haynes, R. J.,J. A. Allen, and E. C. Pendleton. 1988. Re-establishment of bottomland hardwood

forests on disturbed sites: an annotated bibliography. USFWS Biological Report 88.

Hudgins, J. E., G. L. Storm, and J. S. Wakely. 1985. Local movements and diurnal-habitat selection

by male American woodcock in Pennsylvania. Journal of Wildlife Management 49:614-619.

Kelley J. R., Jr., R. D. Rau, and K. Parker. 2007. American woodcock population status, 2004.

USFWS, Laurel, Maryland, USA.

American Woodcock – Final Paper- 18 -

Kelley J. R., Jr., S.J .Williamson, M. A. Banker, D.R. Dessecker, D.G. Krementz, D. G. McAuley, W.J.

Palmer, and T.J. Post. 2008. American Woodcock Conservation Plan.

Klinger, S. 2008. Ring-Necked Pheasant Management Plan for Pennsylvania 2008-2107. Harrisburg,

PA, USA.

Liscinsky, S. A. 1972. The Pennsylvania woodcock management study. PGC Research Bulletin 171.

McAuley, D. G., J. R. Longcore, D. A. Clugston, R. B. Allen, A. Weik, S. Williamson, J. Dunn,

B. Palmer, K. Evans, W. Staats, G. F. Sepik, and W. Halteman. 2005. Effects of hunting on

survival of American woodcock in the Northeast. Journal of Wildlife Management 69:1565-

1577.

McWilliams, W. H., C. A. Alerich, D. A. Devlin, A. J. Lister, T. W. Lister, S. L. Sterner, and J.

A. Westfall. 2004. USFS Resource Bulletin NE-159.

McWilliams, William H.; Cassell, Seth P.; Alerich, Carol L.; Butler, Brett J.; Hoppus, Michael L.;

Horsley, Stephen B.; Lister, Andrew J.; Lister, Tonya W.; Morin, Randall S.; Perry, Charles

H.; Westfall, James A.; Wharton, Eric H;. Woodall, Christopher W. 2007. Pennsylvania’s

Forest, 2004. Resour. Bull. NRS-20. Newtown Square, PA: U.S. Department of Agriculture,

Forest Service, Northern Research Station. 86 p.

Mendall, H. L., and C. M. Aldous. 1943. The ecology and management of the American Woodcock.

Maine Cooperative Wildlife Research Unit, University of Maine, Orono, USA.

Palmer, W. 2008. Management Plan for American Woodcock in Pennsylvania 2008-2017.

Pennsylvania Game Commission, Harrisburg, PA.

Pennsylvania Game Commission. 1996. Pennsylvania’s Wildlife Action Plan. Version 1.0a.

Harrisburg, PA, USA.

American Woodcock – Final Paper- 19 -

Ricklefs, R.E. and G.L. Miller. 2000. Ecology, 4th edition. Freeman and Company. New York, NY,

USA.

Ruffed Grouse Society. 2008. Woodcock hunting survey provides skinny on hunter satisfaction and

trends. Press Release. Coraopolis, PA, USA.

Sauer, J. R., J. E. Hines, and J. Fallon. 2005. The North American breeding bird survey. Results

and Analysis 1996-2005. Version 6.2.2006. U.S. Geological Survey Patuxent Wildlife

Research Center, Laurel, Maryland, USA.

Sepik, G. F., R. B. Owen, Jr., and M. W. Coulter. 1981. A landowner's guide to woodcock

management in the northeast. Maine Agriculture Experimental Station, Miscellaneous Report

253. Orono, Maine, USA.

Straw, J. A., Jr., D. G. Krementz, M. W. Olinde, and G. F. Sepik. 1994. American woodcock. Pages

97-114 in T. C. Tacha and C. E. Braun, editors. Management of migratory shore and upland

game birds in North America. International Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies,

Washington, D. C., USA.

USFWS. 2000. North American Bird Conservation Initiative. U.S. North American Bird Conservation

Initiative Steering Committee. Arlington, Virginia, USA.

USFWS. 2002. Partners in Flight. Arlington, Virginia, USA.

WLPA. 2008. Mission Statement. From the Singing Ground. Vol. 1, No. 2.