Alter Ego #23

-

Upload

twomorrows-publishing -

Category

Documents

-

view

281 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Alter Ego #23

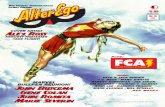

$5.95In the USA

$5.95In the USA

No.23April2003

PLUS:PLUS:

Won

der

Wom

an T

M &

©20

03 D

C C

omic

s

LOST GOLDEN AGE ART OF THE AMAZING AMAZON!

Vol. 3, No. 23 / April 2003Editor Roy Thomas

Associate EditorsBill SchellyJim Amash

Design & LayoutChristopher Day

Consulting EditorsJohn MorrowJon B. Cooke

FCA EditorP.C. Hamerlinck

Comic Crypt EditorMichael T. Gilbert

Editors EmeritusJerry Bails (founder)Ronn Foss, Biljo White,Mike Friedrich

Production AssistantEric Nolen-Weathington

Cover ArtistsBob FujitaniH.G. Peter

Cover ColoristTom Ziuko

And Special Thanks to:Bob BaileyDennis BeaulieuJack BenderJon BerkBill BlackJ.R. CochranBill CookeTeresa R.

DavidsonAl DellingesRoger Dicken

& Wendy HuntRich DonnellyStephen DonnellyGill FoxBob FujitaniGlen David GoldStan GoldbergVictor GorelickGeorge HagenauerRon HarrisMark & Stephanie

HeikeRoger HillTom Horvitz

Bill HowardRichard HowellEd JasterSteve KortéRichard KyleSheldon MoldoffScotty MooreJames PlunkettEthan RobertsCarole SeulingDavid SiegelJoe SimonRobin SnyderMarc SwayzeGreg TheakstonJoel ThingvallDann ThomasAlex TothMichael J. VassalloHames WareRobert K. WienerMarv Wolfman

This issue is dedicated to the memory ofJack Keller Alter EgoTM is published monthly by TwoMorrows, 1812 Park Drive, Raleigh, NC 27605, USA. Phone: (919) 833-8092.

Roy Thomas, Editor. John Morrow, Publisher. Alter Ego Editorial Offices: Rt. 3, Box 468, St. Matthews, SC 29135, USA. Fax: (803) 826-6501; e-mail: [email protected]. Send subscription funds to TwoMorrows, NOT to the editorial offices. Single issues:$8 ($10 Canada, $11 elsewhere). Twelve-issue subscriptions: $60 US, $120 Canada, $132 elsewhere. All characters are © their respectivecompanies. All material © their creators unless otherwise noted. All editorial matter © Roy Thomas. Alter Ego is a TM of Roy & DannThomas. FCA is a TM of P.C. Hamerlinck. Printed in Canada.

FIRST PRINTING.

™

ContentsWriter/Editorial: The Wonder Years . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2Queen Hepzibah, Genghis Khan, & the “Nuclear” Wars . . . . . 4Three “lost” Wonder Woman adventures— with unseen art by H.G. Peter!

Comic Crypt: Flying Discs and Floating Chairs. . . . . . . . . . . . . 19Michael T. Gilbert presents rare art by Simon & Kirby.

Alex Toth on Noel Sickles & Fred Ray. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27From Scorchy Smith to Terry and the Pirates to Tomahawk!

Claude Held, Pioneer Comic Book Dealer . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31Bill Schelly interviews one of the first comics dealers—and gets some great stories.

Jack Keller (1922-2003) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36Dr. Michael Vassallo on an artist who drew men on horseback—and in hot rods.

re: [comments & corrections] . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39FCA [Fawcett Collectors of America] #82 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43P.C. Hamerlinck presents Marc Swayze, Sheldon Moldoff, and Bill Parker.

All the Way with MLJ Section . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Flip Us!About Our Cover: Merciful Minerva! Recently, Carole Seuling, the wife and partner of comics dealer/conventioneer Phil Seuling back in the ’60s and early ’70s, let slip that she owned a never-published piece of original 1940s Wonder Woman art by H.G. Peter. It’sbeautiful as Aphrodite— and once we’d seen it, we were wise as Athena to use it, with Carole’s blessing, as a cover for Alter Ego! Thanks, old friend! [Wonder Woman TM & ©2003 DC Comics.]

Above: By 1958, his last year as Wonder Woman artist, H.G. Peter’s quirky, individualistic art wasn’t all it had been. But he still had a couple of good moves left—one of which was thissplash from Wonder Woman #97, the art for which was offered in a 1993 art catalog. Thanks to Glen David Gold for reminding us about it! Whether Diana’s barebacking a stallion or acarnosaur, she always comes out on top! [©2003 DC Comics.]

& FriendsSection

by Roy ThomasCancelled Comics

Cavalcade—1940s Style

So near, and yet so far...!

Naturally, most comic book stories which get as far as beingscripted, penciled, inked, and even lettered wind up being published.After all, by that time, a reasonable amount of money has usually beenpaid to the writers, artists, and letterers of the material—and if it isn’tused, that expenditure is a dead loss... or at best becomes a tax write-off, like DC Comics’ infamous one of Sept. 30, 1949, touched on inseveral issues of Alter Ego.

Of course, if a comics title is cancelled with scant advance notice,there’s likely to be a bit of spare art and story lying around in somestage of completion; but the publisher has decided, rightly or wrongly,that he/she is better off swallowing the loss of a story (or even a wholeissue) or more, and moving on.

That’s probably what happened in the case of much of the “WrittenOff - 9-30-49” material we’ve seen over the past years, such as “GreenLantern,” “Flash,” “Dr. Mid-Nite,” “Ghost Patrol,” “Little Boy Blueand the Blue Boys,” and other 1940s series. These partly-surviving butnever-published stories were most likely produced not too long beforeeither (a) a particular feature was dropped from an ongoing title, as perthe latter two, or (b) entire mags were cancelled or altered in format, asin the case of the trio of Justice Society members mentioned above. In1948 All-American Comics became All-American Western, leaving noberth for Doc’s exploits—and in ’49 both Green Lantern and FlashComics were cancelled outright, leaving no place for unprinted tales ofthe titular heroes (not to mention Black Canary, The Atom, and

Hawkman) to roost.

Some of the “Flash” and “GL” stories orphaned by these cancella-tions seem to have been prepared even earlier, intended for All-Flash orComic Cavalcade, two super-hero mags which had been deep-sixed in’48 (the former discontinued, the latter transformed into a funny-animal

Queen Hepzibah, Genghis Khan,& The “Nuclear” Wars!

A vintage “Wonder Woman” splash page, with writer William M. Marston (top) and artist Harry G. Peter (middle). As mentioned below, the entire 13-page story thatgoes with this 1940s splash was finally printed in black-&-white in 1974’s The Amazing

World of DC Comics #12. The photo of Dr. Marston is from the Oct. 25, 1940, issue of The Family Circle magazine, while the circa-1910 portrait of HGP by his friend, illustrator

Louis Arata, was sent by Scotty Moore. [Wonder Woman art ©2003 DC Comics.]

Three “Lost” WONDER WOMAN Adventures–––with Never-before-seen Art by H.G. PETER & Scripts by

DR. WILLIAM MOULTON MARSTON

4 Queen Hepzibah, Genghis Khan, & The “Nuclear” Wars!

comic). These tales would have sat on the shelf for a year, awaiting anopen slot that never came. DC’s Sheldon Mayer, who edited all comicswhich starred Flash and/or Green Lantern, was by all accounts usuallythree issues ahead on every mag he handled, so it was inevitable there’dbe a few leftover stories. DC had to simply swallow the loss.

Okay—but how about when a comics title isn’t cancelled—anddoesn’t change format or genre?

Like Wonder Woman.

From her debut in late 1941 through his own return to writing anddrawing in 1948, Shelly Mayer was the editor of all comics in which theAmazon appeared, as well: Wonder Woman, Sensation Comics, ComicCavalcade, and All-Star Comics. Even excluding the latter, in which theoriginal Princess Diana had little to do prior to 1948, that’s six circa-12-page stories every two months once wartime restrictions were lifted:three in her own bimonthly title, one each in two of the monthlySensation, and one in the bimonthly CC. Those 72 pages came underthe joint jurisdiction of editor Mayer and Dr. William Marston, thepsychologist who had been Wonder Woman’s major creator (under thepseudonym “Charles Moulton,” utilizing the middle names of publisherM.C. Gaines and himself). Even the artwork, produced via a shopsystem with veteran artist Harry G. Peter as the primary artist, was doneunder Marston’s supervision, contrary to DC’s usual practice.

Many details about the way Marston worked (and about his

unorthodox private life) were brought to light by Les Daniels in hisdeservedly award-winning 2000 volume Wonder Woman: TheComplete History from Chronicle Books. And I’m glad they were,’cause that frees us, for the most part, from having to surmise about theconditions under which the unpublished stories were produced. Instead,we can simply examine the stories and art themselves.

There were several 1940s “Wonder Woman” stories which werecompleted but not published at the time, three of which were firstprinted in DC mags decades after they’d been prepared:

The 13-page “The Cheetah’s Thought Prisoners,” belatedly saw thelight of day in DC Special #3 (April-June 1969).

An 11-pager, “The Stormy Menace of Goblin Head Rock!”—likewisefeaturing the villainous Cheetah—finally surfaced in Wonder Woman#196 (Sept.-Oct. 1971).

A third left-over “Wonder Woman” exploit, “Racketeer’s Bait,” wasfirst seen (in black-&-white) in DC’s own house-published fanzine, TheAmazing World of DC Comics #12 (Sept.-Oct.1974)

But there were others...

A couple of years back, longtime collector and Wonder Womanenthusiast Joel Thingvall generously mailed me photocopies of severalDC scripts that had come into his possession. Two of these were fullscripts for never-printed “Wonder Woman” tales. Also in the package

This piece of art, recently acquired from the estate of H.G. Peter and offered for auction at an estimate of “$20,000 and up” via Heritage Comics’ Oct. 2002 catalog, is indeed just what it claims: “an incredible piece of comics history.” These would seem to be the artist’s very first sketches of

Wonder Woman, doubtless done in 1941, with the figures roughly 8" tall. The catalog also says his real name was H.G. Roth. Special thanks to Ed Jaster. [Art ©2003 estate of H.G. Peter; Wonder Woman TM & ©2003 DC Comics.]

Three “Lost” Wonder Woman Adventures 5

was a lengthy “WW” synopsis titled “The Sword of Genghis Khan,”which, so far as I can ascertain, was never used for a published“episode,” as Marston referred to them. Both scripts and synopsis seemto have been photocopied years later from the good doctor’s carboncopies (remember carbon copies? hope so, ‘cause no room to explain ’emhere!). This means that any changes made to the script by an editor arelost to us and can only be surmised.

Let’s go over these three items one at a time, starting with....

“Queen Hepzibah’s Revenge!”This one was marked (see below) as “Extra Episode for Quarterly

#2”—by which is probably meant Wonder Woman #2 (Fall 1942). Irecognized the title at once, for Alter Ego had already printed theoriginal splash-page art from this “lost” tale in Vol. 3, #2—and haddisplayed 1/3 of a climactic page in V3#5. It was now apparent that thisstory had been prepared no later than very early 1942, for a summer on-sale.

(Incidentally, the word partly scribbled over the word “Quarterly”looks like “Joy.” If so, it’s tempting to believe it refers to Joy Murchison,who wrote a number of “Wonder Woman” stories for and with Dr.Marston. However, she apparently did not come to work for him till1945.)

Now let’s look at the story itself, beginning with that splash pageagain—or rather, what Marston’s scripts refer to as the “displaypanel”:

It’s always fascinating to go through a story and see how the scriptwas changed (either by an editor, or by the writer at an editor’sdirection—it isn’t always possible to tell which), or to observe how anartist may have interpreted aspects of a script differently from theprecise way it was written.

For example, the script for this splash calls for Wonder Woman to be“sitting on the back of vulture-woodpecker, squeezing its neck with onehand as she fights a flying rhinocerous [sic] with the other.” Artist H.G.Peter instead shows her gripping the winged rhino by its horn so that it’s

being dragged through the air upside-down. Well, I guess that countsas “fighting.”

The splash caption has been rewritten slightly in the finishedversion, so that it now begins with a question that rewordsMarston’s original declarative sentence, to good effect. His secondsentence, “Other terrifying bird-mammals snatch at you,” has beendropped as superfluous. Decent-enough editing.

The single story-panel which Marston wrote in the early daysfor the bottom right corner of the splash page—and which hedescribed on the second page of the script—shows Hepzibah, aringer for the evil Queen in Snow White, sending her unshown“slaves” to “capture my granddaughter who left me to die yearsago.” She wants revenge on the ingrate.

Mayer or his script-editor altered no words in this panel, exceptto correct an error common among comics writers, then and now.The slaves address their mistress as “O’ Queen Hepzibah.” Theapostrophe is incorrect (as is the common use of the word “Oh”in this context); the phrase appears correctly as “O QueenHepzibah.” Hardly an earth-shattering change, but it’s interestingthat someone noticed the minor mistake and corrected it.

The story is a charming one—assuming you have a high tolerance forwhimsy. Diana Prince is interrupted in her secretarial tasks at MilitaryIntelligence HQ in Washington, D.C., by a creature described on p. 2 ofthe script as “a large wild tough looking rabbit. The rabbit is not anordinary looking rabbit—use imagination in drawing him. Butch therabbit has wings. It is sitting on hind legs, front paws leaning against thedesk. It is behind Diana. The rabbit looks amazed at the rapidity withwhich Di is typing. Papers are flying in air.”

Turns out that, being alone in her office, Di decided to type morethan 400 words a minute, which she finds “much too slow.” When Butch

6 Queen Hepzibah, Genghis Khan, & The “Nuclear” Wars!

Page 1 of both script and finished product. You can see the splash bigger inA/E V3#2. Thanks to Jerry G. Bails.[Wonder Woman TM & ©2003 DC Comics.]

19

Simon & Kirbywere arguably the

greatest comic bookcombo of the Golden

Age. Joe Simon focusedprimarily on writing

and inking, whileJack Kirby concen-

trated on penciling.Together they

produced comic bookmagic. Captain

America, The BoyCommandos, Black Magic, and Young

Romance were just a few of their top-sellingcreations.

This issue, we’ve uncovered three previously unpublishedpages from this “team supreme.” Two are from the very

beginning of their partnership, and one is from near its end.Let’s start with...

The Black Cat Mystery!Or, if you prefer, the strange case of “The Comic That

Never Was!”

But before we tell you about Simon & Kirby’s connection tothat caper, we need to talk about Black Cat Comics.

Few comic book series ever had a more schizophrenic history than HarveyComics’ Black Cat. Harvey’s sexy super-heroine of that name debuted in thefirst issue of Pocket Comics in 1941. She switched to Speed Comics in 1942before winning her own title in 1946. By 1949 super-heroes were dying out, soBlack Cat Comics became Black Cat Western with issue #16. Luckily, TheBlack Cat and Linda Turner (her movie star alter ego) looked as sexy onhorseback as she had on a motorcycle, but the experiment lasted only four issues.By #20 the title reverted to Black Cat (minus the “Comics,” but with theunofficial title “The Darling of Comics”)—then changed to Black Cat MysteryComics nine issues later.

The masked super-heroine apparently vanished from the interiors after #29,

Simon & Kirby: Flying Discs and Floating Chairs!

The first “Black Cat” splash—story credited to Alfred Harvey, art to Al Gabriele—from Pocket Comics #1 (Aug. 1941), as reprinted in The Original Black Cat #6 (Aug. ’91).

[©2003 Lorne-Harvey Publications, Inc.]

All Cats Are Black In The Dark!A Gallery of Fabulous Black Cat Firsts. All art featuring The Black Cat

is by Lee Elias. [Art ©2003 Lorne-Harvey Publications, Inc.]

Black Cat Comics #1 (June-July 1946).

Black Cat Mystery Comics #30 (Aug. 1951)—the last cover featuring

the heroine; apparently her finalinterior stories had appeared in #29.

Black Cat Western Mystery #54 (Feb. ’55). The Cat came back!

Black Cat #63 (Oct. ’62). A briefSilver Age revival—with reprints!

Black Cat Comics #12 (July 1948); ourred-haired heroine took to horseback

and cowboy-movie themes four issuesbefore the title was officially changed.

Black Cat Western #16 (March 1949)—the new title.

Black Cat #20 (Nov. 1949)—the finalcover with a western theme.

20 Mr. Monster’s Comic Crypt

Black Cat Mystery #33 (Feb. ’52). Atypical cover from the horror period.By now, the word “Comics” has been

dropped, and with #44 (June ’53)even the word “Mystery” is greatly

reduced in size. Maybe the publisherthought someone would confuse his

comics with Agatha Christie?

A typically well-drawn Lee Elias splashpage from the Golden Age comic, as

seen in the black-&-white reprint The Original Black Cat #4 (June ’91).

Black Cat Mystic #58 (Sept. 1956).Yeah, we didn’t show the cover ofBlack Cat Mystery #57. So sue us!

though she still appeared on the cover of #30. From #30-53 Black CatMystery was a straight horror comic. By the end of that time, thecrusade against horror comics was making Harvey a bit nervous, so inFebruary 1955 they changed it into Black Cat Western Mystery,starring our horse-riding heroine again. Go figure! That lasted preciselyone issue; then the comic reverted yet again to the more streamlinedBlack Cat Western for the next two.

But wait! We’re not done yet! For some reason, the title changedback to Black Cat Mystery for one lone issue (#57), before morphinginto Black Cat Mystic for #58-62. These six Comics Code-approvedbooks featured G-rated science-fiction and supernatural stories bySimon & Kirby, and others. S&K also spearheaded a similar mystery titlefor Harvey, Alarming Tales. More on that later.

Black Cat Comics/Mystery/Western/Mystic was finally cancelled in1958, but returned in 1962 for three more issues. These were giant 25¢comics containing reprints of Linda Turner, the original Black Cat. Thetitle? Why, Black Cat Comics, of course! As I said at the beginning:schizophrenic!

All of which leads to the mystery of...

The Comic That Never Was!Last year, I spotted a very exciting item while surfing the web. Bill

Howard had posted an unpublished Simon & Kirby cover from his

collection. The cover logo indicated it was originally intended for the59th issue of Harvey’s Black Cat Mystery.

But there was no such issue!

As mentioned above, the titled changed to Black Cat Mystic withissue #58. Harvey did publish #59, but with a different cover—and withthe latter name. It was a perplexing mystery, partly solved by BillHoward, who was kind enough to share some background on the page,as related by the collector who sold it to him:

“In the late ’50s Harvey needed to make the transition away from horror into more sci-fi, western, and adventure. They broughtin Simon & Kirby. Black Cat had already been transformed into a‘horror’ book and the name was changed to Black Cat Mystery. Thecover you own was originally intended for issue #59, the final BlackCat Mystery. Alfred Harvey and Simon put their heads together andsurmised that an entirely new title would be better. They launchedAlarming Tales #1 and used the story of the man in the flying chair inthis book. Joe Simon thought that Kirby’s man in the chair was toolarge and did not look like an ordinary person, so he redrew the coverhimself. If you look at the cover of Alarming Tales #1, Kirby iscredited with the cover, but it is all Joe Simon.

“The Black Cat Mystery cover I own is ALL Kirby and infinitelybetter, IMHO, than the published cover to Alarming Tales #1. Infact, Joe Simon himself admitted that Kirby’s rendition, in the end,

Joe Simon’s version of the flying chair—from the published cover of Alarming Tales #1 (Sept. ’57). [©2003 the respective copyright holder.]

Simon & Kirby’s cover for Black Cat Mystic #59 (Sept. 1956).

Simon & Kirby: Flying Discs and Floating Chars! 21

ALEX TOTH on NOEL SICKLES & FRED RAY[ALTER EGO INTRODUCTION: In issue #19 we spotlighted considerable coverageof Fred Ray, artist of some of the most memorable Superman covers ever, as well as themajor artist of the “Tomahawk” series. We’ll have commentary on that issue, for themost part, in A/E #24, but here are veteran artist Alex Toth’s hand-lettered remarks onRay, and on his ‘Sickles Connection,’ received soon after publication of issue #19,precisely as they filled both sides of a postcard. —Roy.]

Alex Toth 27

A Toth art composition—one of many he does for pleasure, which we’rehappy that he shares with us. See another one on p. 29. [©2003 Alex Toth.]

Claude Held,Pioneer Comic Book Dealer

Title 31Comic Fandom Archive

by Bill Schelly[Introduction: Although comic fandom emerged as a recognizableentity in the early 1960s, there were people who collected comic booksfrom the very beginning of the medium. And where there werecollectors, eventually there would be comic book dealers to supply thedemand for back issues. As far as I know, the earliest known comicbook dealer was Claude Held of Buffalo, New York, who beganamassing comics for re-sale in the mid-1940s. While researchingfandom’s “pre-history” for the second edition of my Hamster Pressbook The Golden Age of Comic Fandom, I had the opportunity tochat with Claude about those early days. In the relatively brief timewe talked, he related some wonderful stories about some of the earlydeals he made, and I had the feeling we had only scratched thesurface. But, as I was unable to fit most of the information in mybook, for space considerations, I’m pleased to be able to print the fulltranscript of our talk now. Our conversation took place by telephoneon February 19, 1998; the tape was transcribed by Brian K. Morris.]

BILL SCHELLY: Let’s start with finding out a little about you. Youwere a science-fiction fan as a kid, weren’t you?

CLAUDE HELD: Right. I lived upstairs and Kenny Krueger liveddownstairs. We lived on Fountain Street in Buffalo, New York. Around1937 and 1938, we both became interested in the science-fiction pulpmagazines. I think the first one we ever had was a Thrilling WonderStories. A few months after we got interested in that, a used-book storewas opening in the next block on Carlton Street, and Kenny’s father hadcontracted to do the interior painting. Ken and I got in there the daybefore they opened, and found they had racks and racks of used pulps—Weird Tales, Thrilling Wonder Stories, Amazing, many others—allselling for three cents apiece. But none of us had any money in thosedays. I managed to scrounge up fifteen cents. I even knew which ones Iwas going to pick out—nice big early Wonder Stories. I went in the nextday after school and they were all cleaned out already. Somebody beat

me to them. [laughs] That was my first realdisappointment. Anyway, from then on, both ofus collected science-fiction, bought and sold,

and I think right away I got the idea that maybe I could pick upmagazines and sell them through the mail. This was around 1939, 1940.

SCHELLY: You were about what grade in school at the time?

HELD: Eighth grade. But I didn’t come out with my first real list untilaround ’42 or ’43. I’d like to buy some of that stuff back today. [laughs]

SCHELLY: At those prices.

HELD: You’re not kidding. Well, anyway, after high school, I was in theNavy a couple of years. I was discharged in ’46. I went to the Universityof Buffalo. All my classes were in the morning between eight and elevenor twelve o’clock. That gave me plenty of time for a part-time job, and Igot the idea of opening up a bookstore. So I went to school in themorning, opened up the bookstore from noon until about nine.

SCHELLY: A storefront.

HELD: Right, and the comics started from that. The store was on a busycorner, on Utica near Jefferson in Buffalo. One day this guy who’d justgotten out of the Army pulled up his car outside my store. I happenedto be standing in the doorway at the time. He jumped out of the car andhe said to me, “Do you buy comics?” I said, “Yeah.” At the time, I wasselling old comics for three cents apiece, just like those pulps Imentioned before. Well, he said, “Okay, I’ve got some. What do youpay?” And I said, “A dollar a hundred.” He says, “Okay,” and he wentand parked the car a block or so down the street. When he came back,he had these two stacks. He had tied them up in stacks of a hundred. Hebrought them in the store, and then he turned around and started out. Iasked him, “Where are you going?” He said, “To get some more.” Bythe time he was done, he’d brought in some 1700 comics. [laughs]Remember, I had just started this store, and I didn’t have a hell of a lot

Claude Held (at left) with an unknown fan, 1964—flanked by the covers of vintage issues of two pulp

magazines he mentions: Weird Tales (May 1934)cover-featuring Conan, and Amazing Stories

(Feb. 1940) spotlighting an Eando (Otto) Binder taleof Adam Link, Robot. Both Conan and Adam Link

—as well as Binder—would make their mark in comicbooks between the early 1940s and the 1970s.

[©2003 the respective copyright holders.]

of dough. I said to him,“Jeez, I didn’t think youhad that many!” I woundup getting the 1700comics for $15.

SCHELLY: Wow.

HELD: Now, just stopand think. This was 1946.How would you like tohave those today?

SCHELLY: I’m sure thatit’s just an incrediblebunch of comics. Howcould it not be?

HELD: It was fantasticbecause all of the earlyDCs, the More Funs, allthat type of stuff was inthere. So I put them inthe back room. The stufffrom the last few years,like 1943 to 1946, I putout at three cents apiece.The older ones I liked, soI kept them for myself.Now, going forward a

couple of years, say to ’49 or ’50. Are you familiar with Bill Thailing?

SCHELLY: Yes, I’ve spoken to him a couple of times. He was also anearly dealer, who was very important in the early 1960s, getting backissues to the folks like Raymond Miller who were writing articles forAlter Ego and other early fanzines.

HELD: Okay. Did you also talk to Mickey Sullivan?

SCHELLY: That name doesn’t ring a bell.

HELD: Here’s the story on those two people. I don’t know which onecame in first. I think it was Bill. There was another book dealer down onGenesee Street named Keel Book Store. When people would ask for oldmagazines, he would send them up to my place. So one day BillThailing, who lived in Cleveland, Ohio, was referred to me. Bill came inmy store and asked if I had any old comic books.

SCHELLY: He came all theway up to Buffalo, huh?

HELD: Yeah. This is around1950 or ’51. Well, I wasthinking of the ones I had inthe back that I had beenreluctant to sell—so I pulledout some and sold them tohim for, I think, a dimeapiece. He bought some, andthen he came back a fewmonths later and bought somemore. But I didn’t feel toohappy about selling thesethings, because I actuallywanted to keep them longer.So the price went up to aquarter, and I think hesquawked. [laughs] But hebought a bunch more.

SCHELLY: What about Mickey Sullivan?

HELD: Mickey lived down in Erie, Pennsylvania. He was just a kidthen. He used to come up with his mother. This was when I was at thequarter-apiece stage. He thought I was a highway robber for asking thatmuch. I didn’t even want to sell them at that price… but he wouldalmost cry, and his mother would break down and say, “We came all thisway, so we’ll get these, this, or that….” Or whatever. And I had nowcome to the point where I really wanted to save what old comics I stillhad from that original deal.

SCHELLY: You must have had other sources for comics, besides thatoriginal bunch.

HELD: Yes! Sometime around 1953 or 1954, there were big police raidson the book stores in Buffalo. Some of them were selling what theycalled “striptease pictures.” Well, Old Man Keel of Keel’s Bookstore onGenesee Street, by this time, had sold out to a fellow who was arrestedfor that very reason, and he needed money for a lawyer. And this fellowhad been putting comic books aside back in the ’40s. After talking on thephone, I realized he had a lot of really good ones. He asked me if Iwanted to buy them. We finally agreed on a price of a nickel apiece.There were a thousand or 1200 comics in this deal. When I went homethat night, he had stacked up the side porch of my house with cartons ofcomics. That was one of the best sights of my life. I remember specifi-cally that he had at least ten, twelve of Superman #2 and Superman #3in Near Mint condition. Another big one that he had was Planet #1. Hehad a handful of those. Now, I’m not kidding you. This happened.

SCHELLY: Was this when you started putting out a list of comicbooks for sale?

HELD: Not yet. I was still at the point of putting them aside. But I hadbeen putting out a list of fantasy books and magazines for sale allthrough the ’40s and ’50s. It wasn’t until sometime in the late 1950s thatI started to put some comic books on those lists. Again I was treated likea highway robber. A lot of people were infuriated that I was charging50¢ or a dollar for a 1930-something comic book. They grumbled… butthey bought them anyway. Then gradually I started putting out lists ofmostly comic books, in the early 1960s. Phil Seuling and HowardRogofsky didn’t come in until a couple of years later.

SCHELLY: Right, ’62, ’63. What about Bill Thailing?

HELD: He had been selling comics to other collectors through the mail,but not putting out lists until about this same time. Also, Malcolm

“All of the early DCs, the More Funs, all thattype of stuff” was in boxes in a car that

pulled up in front of Claude’s first store in 1946.Like maybe a copy of More Fun Comics #62(Dec. 1940), with Spectre cover probably by

Bernard Baily? Today’s Overstreet Guide price innear mint: $3200. Sigh.... [©2003 DC Comics.]

“I remember specifically that [Old Man Keel] had at least ten, twelve of Superman #2 and Superman #3 in Near Mintcondition. Another big one that he had was Planet #1. He had a handful of those.” Now you’re making us cry, Claude!

[Superman covers ©2003 DC Comics; Planet #1 cover ©2003 the respective copyright holder.]

32 Comic Fandom Archive

by Dr. Michael J. VassalloThe comic book world lost one of its most durable mainstays of the

1950s and 1960s when Atlas/Marvel and Charlton artist Jack Kellerpassed away on January 2nd at the age of 80, after a short illness.

Keller had a long and distinguished career spanning the years 1941-1973 on a score of features for numerous comics companies, but is bestknown for long runs on two in particular: Kid Colt Outlaw atAtlas/Marvel, and the entire genre of hot rod and racing cars titles atCharlton.

Jack Keller was born on June 16, 1922, in Reading, Pennsylvania.Except for a short period early in his career, he would spend his entirelife there. As was the case of almost every comic book artist from hisgeneration, his earliest artistic idols were Milton Caniff, Alex Raymond,and Hal Foster, and as a child he devoured their newspaper strips,especially Terry and the Pirates.

In 1941, fresh out of high school and with no formal art education,Keller created, wrote, and drew a comic book feature called “TheWhistler,” which was accepted for publication by Dell Comics andappeared in the title War Stories, issue #5. By his own admission it wasextremely crude, but it somehow opened the door to a job in 1942-43with Busy Arnold at Quality Comics. Among a handful of differentfeatures, including inking “Blackhawk” and doing artwork for featureslike “Manhunter” and “Spin Shaw,” Keller also did backgrounds for LouFine on The Spirit while Will Eisner was in the service during WorldWar II.

Keller was now living in New York City fulltime at the 34th StreetYMCA, and his quarters were cramped and tiny. Making the roundsover the next few years, he had stops at Fawcett drawing “Johnny Blair,”at Fiction House drawing series such as marine pilot “Clipper Kirk,”“Flint Baker,” and “Suicide Smith,” and at Hillman on “The Boy King,”“The Rosebud Sisters,” and various crime features. As the decade closed,Keller did work for Charles Biro and Bob Wood at Lev Gleason onCrime Does Not Pay, Crime and Punishment, and various westernfeatures in roughly 1949-50.

Jack Keller’s last two major accounts in his comic book career wouldbe the ones on which he would leave his lasting mark. In 1950 Kellershowed up on editor Stan Lee’s Timely Comics doorstep and wouldbegin an association that would last the entire decade and beyond. Atthis point, publisher Martin Goodman had just dissolved the long-standing Timely bullpen. Known as the “cataclysmic closet catastrophe”(a phrase coined by Stan Lee in his recent “bio-autobiography”), thestory goes that Goodman opened a closet to find a six-foot stack ofbought but never-printed artwork. Going ballistic, he instructed Lee tofire the staff, and everyone suddenly went freelance.

Jack Keller shows up right at this moment and is immediately givenwork on stories for western titles, early pre-Code horror, and even therare romance story. His most prolific “early” Marvel work, though, wasin the dizzying array of redundant Timely crime titles. This work isseverely overlooked and under-appreciated by many who considerKeller’s career. Never a spectacular or flashy artist, Keller’s crime storiesnevertheless had an urban grittiness perfectly suited to the subjectmatter, with a style similar to that of crime-comic colleague VernHenkel, and two steps above the Timely crime-comic bullpen fare of

1948-49. At least 75% of Keller’s crime stories were scripted by CarlWessler, who wrote more crime stories than any other Timely scribeduring this period. Often entire issues in 1950-51 were Wessler-scripted.Look for these stories in titles like Amazing Detective Cases, KentBlake, All-True Crime, Justice Comics, Crime Exposed, Crime Can’tWin, and Crime Must Lose.

As 1953 rolled in, Keller added more horror and war stories to hiscredits, but a western feature he had drawn since 1951, Kid ColtOutlaw, began to take prominence. When Stan Lee gave Keller KidColt in 1951, it was nothing more than another assignment, but whileother artists came and went on various features (Joe Maneely on BlackRider, Wyatt Earp, Ringo Kid, Whip Wilson, The Gunhawk... SydShores on Two-Gun Kid... John Romita on Western Kid... Werner Rothon Apache Kid... Doug Wildey on Outlaw Kid, etc.), Keller never reallyleft Kid Colt and drew his adventures, both in his own long-runningtitle and also in the anthology title Gunsmoke Western, right up to1957. Throughout this long run, he would continue to do western fillers,but his non-western work practically vanished by 1955 as his entireoutput was dedicated to the western genre.

In the spring of 1957 the infamous “Atlas Implosion” left Keller andscores of artists without their main source of freelance income.Goodman and Lee pared down the bloated line from a high of aboutseventy titles to a paltry sixteen, frantically securing distribution for thebooks from National/DC’s distributor, Independent News, and Stan Leebegan to use backlogged inventory for the remaining eight books permonth.

Jack Keller(1922-2003)

36 Jack Keller

Sorry we don’t have a photo of Jack Keller, but here’s a splash pagefeaturing the continuing hero with which he’s most associated, from Kid Colt Outlaw #80 (Sept. 1958). Thanks to Doc Vassallo.

[©2003 Marvel Characters, Inc.]

[Art

©20

03 S

held

on M

oldo

ff &!P

.C. H

amer

linck

; Cap

tain

Mid

nigh

t TM

!&!©

2003

the

res

pect

ive

TM!&

cop

yrig

ht h

olde

r.]

[FCA EDITORS NOTE: From 1941-53, Marcus D. Swayze was atop artist for Fawcett Comics. The very first Mary Marvel charactersketches came from Marc’s drawing table, and he illustrated herearliest adventures, including the classic Mary Marvel origin story inCaptain Marvel Adventures #18 (Dec. ’42); but he was primarilyhired by Fawcett Publications to illustrate Captain Marvel stories andcovers for Whiz Comics and CMA. He also wrote many CaptainMarvel scripts, and continued to do so while in the military. AfterWorld War II he made an arrangement with Fawcett to produce artand stories on a freelance basis out of his Louisiana home. There hecreated both art and story for The Phantom Eagle in Wow Comics,in addition to drawing the Flyin’ Jenny newspaper strip for BellSyndicate (created by his friend and mentor Russell Keaton). Afterthe cancellation of Wow, Swayze drew for Fawcett’s top-selling line ofromance comics, including Sweethearts and Life Story. After thatcompany ceased publishing comics, Marc moved over to CharltonPublications, where he ended his comics career in the mid-’50s. Marc’songoing professional memoirs have been FCA’s most popular featuresince his first column appeared in FCA #54, 1996. Last issue and inthis installment, Marc shifts into reverse, reflecting upon his pre-Fawcett Publications period. —P.C. Hamerlinck.]

IT WAS FUN. A bit bewildering at first, but verypleasant, the way things were turning out. One week a milkdeliveryman, the next, the assistant to a real professionalartist, creator of a real syndicated comic strip.

It was fun… my first job as a salaried artist, but in notime at all I was bugged by the urge to reach out for higherthings… to move on up. My employer knew it. It was hewho said after a week or so, “You’re a natural.” I took thatto mean I was slated for the big time, whatever andwhenever the “big time” was.

We were in a small community of about 12,000. I hadarranged to take my meals at a boarding-house where manyof the high school teachers dined… and they became myfriends. Russell Keaton was a sincere, personable, experi-enced professional whose comic strip had made its debutonly a few months before my arrival. It was 1939.

My first shot at the world ahead was to submit samples toWalt Disney in 1940. I’m not sure what I had in mind. Abetter job? A move up? I should have known that finishedart, in full color, was not the way to show a prospectiveemployer what you could do. Better to have sent thediscarded sketches of the work in progress. However, theanimated films were not hiring at the time, they said, so itdidn’t matter.

I took a stab at the gag cartoon game. Gags were thegoing thing as the ’30s came to a close. Major publishers were

(c) mds

By

[Art & logo ©2003 Marc Swayze; Captain Marvel © & TM 2003 DC Comics]

An action sequence from “Captain Marvel Introduces Mary Marvel” in CMA #19, 1942. Art by Marc Swayze. [©2003 DC Comics.]

Marc’s “first shot at the world ahead.... submit[ting] samples to Walt Disney in 1940.” [Art ©2003 Marc Swayze; Donald Duck & Goofy

are registered TM of Walt Disney Productions.]

44 Marc Swayze

by P.C. HamerlinckHe came up with a little six-letter word that has become a part of the

English language.

While the genesis of the World’s Mightiest Mortal has been told invarious versions in a variety of places, what do we really know aboutBill Parker, the often-overlooked writer/editor who combined elementsof old literature, the Bible, mythology… and that little six-letter word...to produce a truly classics-derived modern-day folk tale all of its own—a tale which captivated readers in the 1940s and has withstood the test oftime all the way to slick 2003. Parker far exceeded his job duties when hewas asked by his publisher to “come up with a character like Superman.”

Parker was the catalyst of the world known as Captain Marvel,whose occupants included, amongst many wonderful inhabitants, hisalter ego Billy Batson, a mysterious stranger in an old abandonedsubway, an ancient Egyptian wizard who gave Billy his powers, ascheming proverbial “mad scientist” named Dr. Sivana, and his stunningdaughter Beautia.

The World’s Mightiest CollaborationBill Parker’s artistic collaborator, Charles Clarence Beck, was always

adamantly clear to point out to the present author—and to the entireworld—that he had very little, if anything, to do with the success ofCaptain Marvel, one of the top selling characters during the Golden Ageof Comics.

While Beck modestly felt that any and all credit regarding thecreation and popularity of the Big Red Cheese should go to Parker, theother writers, and Fawcett’s editorial staff—and that the stories, not theartwork, were always first and foremost of greatest importance—it isquite clear that Beck contributed more to the success and reader-popularity of Captain Marvel than any other of the individuals atFawcett Publications who participated in the birth and development of

the character over its 13-year lifespan.

In 1939, at the age of 29, Beck’s professional experience and skill as acartoonist was a vital factor as he fleshed out the first Captain [Thunder]Marvel drawings. Beck’s visual delineation of the hero and hiscontinuous enthusiasm for the character, plus his supervision of manyFawcett artists who eventually contributed to the expanding MarvelFamily of titles, made Fawcett comic books superior in quality to mostof the field.

Beck’s contribution did not stop with the artwork. He also made veryvaluable contributions to the storylines, the stories themselves, and theshaping of the personalities of characters such as Mr. Mind, SterlingMorris, Ibac, Mr. Tawny, and the rest of the cast that really distinguishedthe stories in the Captain Marvel canon. It was Beck—along withprolific Captain Marvel writer Otto Binder—who over the course oftime developed the unique, whimsical, tongue-planted-firmly-in-cheek,kid-and-adult-pleasing humor that was lightly inserted into the stories,setting Cap apart from the other super-characters that were appearingvirtually overnight.

According to Fawcett’s long-time editorial director Ralph Daigh,Beck had complete authority to change, edit, and adapt any of thepurchased scripts. It was these additional skills that helped develop theconsistency of the storylines and characterizations, as Beck transferredthe typewritten scripts to drawings. Obviously, without Beck’s talent,skill, and countless contributions to Captain Marvel, something fardifferent would have developed from the early suggestions andconcepts—or, as Daigh himself once concluded, perhaps nothing at all.

That said, there still seems to be a general consensus agreeing withBeck’s assertion that Bill Parker should be the one given top billing forcreating the world accepted as Captain Marvel. Parker produced the firsttyped manuscript that marked the birth of the character, including asummary description and the very first script. He also created and wroteall of Fawcett’s first comic features in Whiz Comics, including SpySmasher, Ibis The Invincible, Golden Arrow, Lance O’Casey, Dan Dare,and Scoop Smith. Shortly thereafter, he created Bulletman, the cover starof Nickel Comics.

A Hero Is BornCaptain Billy Fawcett and his company Fawcett Publications had

already established themselves as a leading forcein the publishing field,

beginning first withtheir saucy humormagazines (such asCaptain Billy’s Whiz-Bang) and, uponrelocating fromMinnesota to offices inNew York City andGreenwhich, Connecticut,various movie magazines.The decision to develop andproduce a new super-herotype of character in the still-infant comic book field wasmade at one of Fawcett’smonthly meetings of

Major ParkerThe Life of BILL PARKER... and His Mightiest Creation

The Life of Bill Parker 47

Characters co-created by Bill Parker for the first issue of Whiz Comics (Feb. 1940) included Captain Marvel, Ibis the Invincible,Dan Dare, Lance O’Casey, Golden Arrow, Scoop Smith, and the still-shadowy Spy Smasher. Cap, Ibis, & Spy Smasher weredrawn by C.C. Beck, Golden Arrow by future CM artist Pete Costanza, Lance by Bob Kingett; artists of Dan Dare and Scoop

Smith unknown. [©2003 DC Comics.]

by J.R. CochranEdited by P.C. Hamerlinck

Looking back on his Golden Age comics career, a career that includedeverything from Hawkman to Captain Midnight to This Magazine IsHaunted, Sheldon Moldoff says that Fawcett was his favorite shop: “Ofall the companies I worked for, Fawcett was the best.” Moldoff beganworking for Fawcett Publications in 1945.

If the pay rates were pretty much the same across the board,Fawcett’s editorial staff was a lot more outgoing than other shops, hesays. “The editors were much friendlier at Fawcett. Stan Lee ran Marvelwith an iron fist, and DC had a flock of editors driven by rivalry of eachother.”

Will Lieberson, who was executive editor at Fawcett, was alsoMoldoff’s favorite comics editor. “He was the only editor I ever becamefriends with. We hit it off right from the beginning. We socialized andremained friends until he passed away five or six years ago. I believe hehad a heart attack.”

Moldoff, who makes his home in Florida, also has fond memories ofLieberson’s editorial team, including Wendell Crowley, Dick Kraus, RoyAld, and Virginia (Ginny) Provisiero.

“Fawcett Was The Best!”Golden Age of Comics Great SHELDON “SHELLY” MOLDOFF

on His Years with Fawcett Publications

Recent Captain Marvel commission art by Moldoff—and a 1999 photo of Shellyand his late wife Shirley (the pair on the left) at WonderCon, with two other of

the earliest artists to work for DC Comics: cover illustrator Creig Flessel (standing)and Zatara creator Fred Guardineer. Photo courtesy of David Siegel. [Art ©2003

Sheldon Moldoff; Captain Marvel & logos TM & c DC Comics.]

Shelly worked on the licensed aviator/super-hero Captain Midnight for several years. This art is from Captain Midnight #54 (Aug. 1947). Hope you

caught Alter Ego’s extended coverage of this radio-born super-star, last issue.[©2003 the respective copyright holder.]

50 Sheldon Moldoff

[Art

©20

03 B

ob F

ujita

ni; H

angm

an T

M &

© A

rchi

e Co

mic

Pub

licat

ions

, Inc

.]

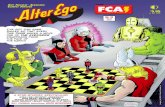

$5.95In the USA

No. 23April2003

Spotlight onGolden &

Silver AgeMasters

BOBFUJITANI

JOHNROSENBERGER

VICTORGORELICK

Plus Rare Art& Artifacts By:

H.G. PETER“CHARLESMOULTON”JOE SIMONJACK KIRBYALEX TOTHFRED RAY

NOEL SICKLESDAN BARRYLEE ELIAS

NEAL ADAMSCARMINEINFANTINOLOU FINE

JACK KELLERMARC SWAYZE

C.C. BECKBILL PARKER

SHELLY MOLDOFFMICHAEL T.

GILBERTROGER HILL

BILL SCHELLYJIM AMASH

P.C. HAMERLINCK& MORE!

ALLTHEWAYWITHMLJ!MLJ!

SPECIAL SECTION

Han

gman

TM

& ©

2003

Arc

hie

Com

ic P

ublic

atio

ns, I

nc.

Alter EgoTM is published monthly by TwoMorrows, 1812 Park Drive, Raleigh, NC 27605, USA. Phone: (919) 833-8092. Roy Thomas, Editor. John Morrow, Publisher. Alter Ego Editorial Offices: Rt. 3, Box 468, St. Matthews, SC 29135, USA. Fax: (803) 826-6501; e-mail: [email protected]. Send subscription funds to TwoMorrows, NOT to the editorial offices. Single issues:$8 ($10 Canada, $11 elsewhere). Twelve-issue subscriptions: $60 US, $120 Canada, $132 elsewhere. All characters are © their respectivecompanies. All material © their creators unless otherwise noted. All editorial matter © Roy Thomas. Alter Ego is a TM of Roy & DannThomas. FCA is a TM of P.C. Hamerlinck. Printed in Canada.

FIRST PRINTING.

™

ContentsWriter/Editorial: All the Way with MLJ!. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2Call it MLJ—Archie—the Mighty Comics Group—it’s definitely had its moments!

“Fuje” for Thought! . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3Golden Age artist Bob Fujitani talks with Jim Amash about The Hangman, Crime Does Not Pay,Flash Gordon, and lots of other neat stuff!

John Rosenberger... the Jaguar of the Comics!. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21Roger Hill’s fly-on-the-wall look at the artist of The Fly, The Jaguar—and Lois Lane!

“The Hangman” Cometh! . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42Archie editor Victor Gorelick on his four decades with Riverdale and super-heroes.

For Wonder Woman, Mr. Monster, & FCA . . . . . . . . . . Flip Us!About Our Cover : What can we say? Though it’s been years—pushing sixty, in fact—since helast did a Hangman comic, master artist Bob Fujitani drew this powerful, moody illustration forinterviewer Jim Amash, and allowed us to use it as our cover. But Roy can’t complain—’causeFuje gifted him with the layout! Black-&-white versions of both can be viewed on page 3—sowhat’re you waitin’ for? [Art ©2003 Bob Fujitani; Hangman TM & © Archie Comic Publications,Inc.]

Above: Here’s another Hangman-and-noose shot drawn by Bob Fujitani, as restored (withgrey tones added) for Bill Black’s Golden-Age Men of Mystery #9 (1998). Thanks to Markand Stephanie Heike, as well. See ads for Bill’s AC Comics elsewhere in this issue—and doyourself a favor by ordering a few. [Hangman TM & ©2003 Archie Comic Publications, Inc.;restored art ©2003 Bill Black.]

Vol. 3, No. 23 / April 2003Editor Roy Thomas

Associate EditorsBill SchellyJim Amash

Design & LayoutChristopher Day

Consulting EditorsJohn MorrowJon B. Cooke

FCA EditorP.C. Hamerlinck

Comic Crypt EditorMichael T. Gilbert

Editors EmeritusJerry Bails (founder)Ronn Foss, Biljo White,Mike Friedrich

Production AssistantEric Nolen-Weathington

Cover ArtistsBob FujitaniH.G. Peter

Cover ColoristTom Ziuko

And Special Thanks to:

All The WayWith MLJ!

Section

Bob BaileyDennis BeaulieuJack BenderJon BerkBill BlackJ.R. CochranBill CookeTeresa R.

DavidsonAl DellingesRoger Dicken

& Wendy HuntRich DonnellyStephen DonnellyGill FoxBob FujitaniGlen David GoldStan GoldbergVictor GorelickGeorge HagenauerRon HarrisMark & Stephanie

HeikeRoger HillTom Horvitz

Bill HowardRichard HowellEd JasterSteve KortéRichard KyleSheldon MoldoffScotty MooreJames PlunkettEthan RobertsCarole SeulingDavid SiegelJoe SimonRobin SnyderMarc SwayzeGreg TheakstonJoel ThingvallDann ThomasAlex TothMichael J. VassalloHames WareRobert K. WienerMarv Wolfman

This issue is dedicated to the memory ofJack Keller

by Jim Amash[INTERVIEWER’S NOTE: BobFujitani, who often signed his name“Fuje,” has lived the freelancer’s lifeas much as anyone has. He spent manyyears as an assistant/ghost artist forlegendary artist Dan Barry on theFlash Gordon newspaper comic strip.Bob’s adaptability served him wellfor every task demanded of him,from Quality Comics to FlashGordon to Prince Valiant, andwith many other companies inbetween. His career serves as awitness to the trials of a comicsartist, and of the people heworked with. And he sounds justlike Bill Goodwin, old-timeradio announcer for Burns andAllen. —Jim.]

JIM AMASH: I usually start offwith this basic question. Whereand when were you born?

BOB FUJITANI: I was bornOct. 15, 1921 in Kripple Creek,N.Y., which is a suburb ofKingston. We moved toGreenwich, Connecticut, when Iwas two years old and I’ve lived here ever since. I have two brothers, butthey weren’t artists.

JA: What led you to become an artist?

FUJITANI: I was always artisticallyinclined. When I was in grade school, Ibecame fascinated with drawing. I readthe Journal-American and they hadgreat Sunday strips. I remember at theage of twelve being fascinated withFlash Gordon, and Jungle Jim, whichwas the strip above Flash. I copied thatstrip for the school newspaper, in AlexRaymond’s style. I loved the junglestuff: lions, tigers, foliage. It’s funnythat, years later, I’d be connected withAlex Raymond because of the FlashGordon strip. A lot of guys made aliving off Alex Raymond.

JA: Those who didn’t make a livingoff Milton Caniff.

FUJITANI: Exactly! Newspaper stripsgot me interested in drawing. PrinceValiant came out later and I loved it,too. That strip took up an entire pageand it was gorgeous. Foster also gotspecial coloring because the strip wasso important to the paper. But I alwaysthought Alex Raymond, in somerespects, was a better artist than Foster.Raymond drew better figures, but theywere both the best.

Al Williamson was almost a clone of Raymond. He really shouldhave been the successor to Raymond on Flash [NOTE: Williamson did

“Fuje” ForThought!

A Candid Conversation with Golden Ageand Flash Gordon Artist BOB FUJITANI

A recent photo of Bob, his wife Ruth, and their dog Fred—flanking his layout and finished artwork of the splendid Hangman illo he did for Jim Amash—and incidentally for our cover. [Art ©2003 Bob Fujitani;

Hangman TM & ©2003 Archie Comic Publications, Inc.]

Bob Fujitani 3

do several Flash Gordon comic books in the 1960s and in the early‘90s. —Jim], because he had that style nailed down. I’m sure peoplemust have told him that.

The syndicate [King Features] used to get letters from readers, andthey’d pass them on to Dan Barry. Every once in a while, someonewould ask, “Whatever happened to the old Flash Gordon I remember?”

JA: As good as Dan Barry was, I know some people hate to see astylistic change in their newspaper strips. People don’t like change.

FUJITANI: Very true. When you take over a strip, you should do ityour way. But I finally realized, after all these years, if you take over astrip and want it to succeed, you have to make it look like the originalartist did it. That’s what people expect.

JA: I agree. I see you went to the American School of Design.

FUJITANI: Which no longer exists. This was after high school, and Iwas there about a year and a half, from 1939 until 1940. That’s where Imet Tex Blaisdell and how I got into comics. It was a two-year coursethat I didn’t finish because I got into comics. Fred Kida went to theschool, too. He was a great artist and a good friend. He wasn’t so greatin art school, but he really developed into a top talent.

Tex had been there a year ahead of me, and one day he called me,saying, “Hey. You want a job?” Jobs were scarce then because we werestill coming out of the Depression. It was a dream come true. Tex toldme to get some samples and rush down to Tudor City on 42nd Street,where Bill Eisner had his studio. I didn’t even take the subway. I think Iran down there from 58th Street. I showed Eisner my samples and hehired me at $5 a day, 25 bucks a week.

JA: Eisner had separated from Jerry Iger by this point, right?

FUJITANI: Right. Eisner had a deal with Quality Comics and publisherBusy Arnold; he was doing “Uncle Sam” and “Blackhawk.” ChuckCuidera was there, sitting by Tex Blaisdell’s right, doing “Blackhawk”[in Military Comics]. Tex was like the boss of the shop for Eisner. NickViscardi [Cardy] was doing “Lady Luck” and Bob Powell was doing afeature, but I forget the name of it; it ran in the back of the Spirit sectionfor newspapers. I sat next to Viscardi, and Tex and Chuck sat behind me.

JA: Chuck Mazoujian was out of the shop by that time?

FUJITANI: Yes. They used to talk about him, but I never met him. LouFine was upstairs in his own office. I heard Busy Arnold paid the renton Lou’s offices.

JA: This must have been before Lou Fine moved to Stamford, Conn.

FUJITANI: That’s possible. Gill Fox, the editor at Quality, was inStamford. All the artists thought the world of Lou Fine. He was thegreatest. When I first saw his work—Tex introduced me to him—I wasastounded. I remember talking to my art teacher and I told him what agreat artist Lou was. My teacher said, “You shouldn’t be doing that kindof stuff.” He thought I should be painting.

JA: What do you remember about Tex Blaisdell?

FUJITANI: He was a big jokester. He was a big, tall man, about six footsix. He towered over everybody and had curly blond hair and huge blue

4 “Fuje” For Thought

We’ll get back to the Dan Barry/Bob Fujitani Flash Gordon later, but here’s their strip for Dec. 27, 1980, repro’d from the original art, loaned to us by Bob.[©2003 King Features Syndicate.]

“All the artists thought the world of Lou Fine.” We printed much of Fine’sstunningly-drawn “Black Condor” art from Crack Comics #17 (Oct. 1941) in

Alter Ego #17, but here’s a page we couldn’t squeeze in there. Repro’d from aphotocopy of the original art, courtesy of Dennis Beaulieu. [©2003 DC Comics.]

Bob Fujitani 5

eyes. His real name was Philip, but we called him Tex. I think he wasfrom Texas. Bill Eisner liked him.

Eisner was a stickler for storytelling. He didn’t care how fancy theartwork was. He stressed the fact that he didn’t like any design in thepanel. “Don’t worry about design or whether it’s balanced or not. Theimportant thing is to tell the story.” He was probably right.

When Bill wasn’t there, Tex was in charge. You know, when I firstgot there, I didn’t know anything about comics. Tex did breakdowns forthe shop artists. He was a good artist.

JA: What were you doing when you started there?

FUJITANI: I was penciling. I had to pencil three pages a day.

JA: Three pages a day? For five bucks?

FUJITANI: [laughs] Yeah. I may be wrong... it may have been twopages a day. I remember Bill Eisner came in one day; he was alwaysfighting deadlines and he had his own office, adjoining ours. He wasdoing The Spirit and trying to oversee us, too. He said, “Things aregetting out of hand here. I’m going to start making work sheets so I’llknow what’s going on.” He said we had to start doing three pages a day.

JA: For $5? He was making good money off of you.

FUJITANI: Yes, he was.

JA: I know Chuck Cuidera was unhappy with Eisner over that.

FUJITANI: I know. Chuck was a slow worker, but very thorough. I canremember him drawing a “Blackhawk” scene with the charactersmarching towards the reader. Chuck was a stickler for detail and gettingthose boots right. Boots have a certain way of making folds at the ankle.And there’s Chuck, with an Alex Raymond swipe in one hand, anddrawing those boots with the other. He was sweating it out just on thoseboots. Eisner didn’t like that because he didn’t think it was important.But to an illustrator, it was important. Eisner wasn’t an illustrator, hewas a storyteller.

JA: Chuck admitted to me that he was a slow penciler. That’s why heonly inked, later on. And Chuck was a tough guy. Did he have a chipon his shoulder?

FUJITANI: I thought so. He had a rough vocabulary.

JA: Cuidera and Eisner both claim they created “Blackhawk.” Doyou have an opinion on this?

FUJITANI: I don’t know for sure, though I wouldn’t be surprised ifEisner was the creator. I know Chuck was the original artist, and heprobably created the visuals, but I imagine Eisner created the idea. Ican’t say it for a fact, though.

JA: Well, Eisner created “Doll Man,” The Spirit, and many otherfeatures for Quality Comics, so it makes sense to me.

Could this splash from Military Comics #3 (Oct. ‘41) be the page Bob Fujitanimentions wherein the Blackhawks were marching toward the reader andartist Chuck Cuidera insisted on getting the boots “right,” to boss Will

Eisner’s chagrin? A/E editor Roy Thomas was surprised to discover, whenporing over The Blackhawk Archives, Vol. 1, that he actually preferred

Cuidera’s art on the team to that of the great Reed Crandall, who took overthe drawing chores with Military #12. Do yourself a favor—pick up this

astounding Archives volume! [©2003 DC Comics.]

In the weekly Spirit comic supplement, Powell drew the “Mr. Mystic” feature;this 1944 page (from a 4-pager) is repro’d from a photocopy of the original

art, thanks to Al Dellinges. [©2003 Will Eisner.]

Conducted & Transcribed by Jim AmashJIM AMASH: When did you start working for Archie Comics?

VICTOR GORELICK: October 4, 1958. I was seventeen and a half. Istarted out working as an art assistant, doing art corrections. One of myfirst jobs was to take the cleavage off the Katy Keene drawings. BillWoggon used to draw low necklines, and the Comic Code Authoritydidn’t want to show any cleavage. So I had to take out navels andcleavages. That’s how things were then.

JA: So you were there when Simon and Kirby started doingAdventures of The Fly and The Double Life of Private Strong?

GORELICK: Yes, I was. Iremember seeing them comeup to the office, but the onlyone I really rememberspeaking to was Joe Simon. Iwas only a mere art assistant,so I had no reason to havecontact with them. RichardGoldwater was the managingeditor at that time.

JA: Who was Goldwater’sassistant?

GORELICK: It wasSheldon Brodsky. He hadgraduated from the School ofIndustrial Art, which is nowthe School and Art andDesign. I went to schoolthere, too. Brodsky hadstarted at Archie a year or sobefore I did. They were looking for someone to replace Dexter Taylor,who was leaving his art staff job to go freelance. Dexter was going towork on Little Archie, which was an 80-page book, and Bob Bolling,the regular artist, needed assistance. Dexter had done some Little Archieartwork and drew the Super Duck covers.

JA: Why did Archie decide to go back into the super-hero market?

GORELICK: I’m not sure, but I could venture to guess that Simon andKirby approached the company with the idea. I’m sure that JohnGoldwater [one of the company founders] had a lot to do with bringingthem on board at that time. I do remember Simon and Kirby coming upto Richard Goldwater’s office and having a meeting about it. After that,they started doing The Fly, and then Private Strong, which was anupdate of the original Shield.

JA: Why did Private Strong only last two issues? Was it because DCthreatened to sue Archie over the character?

GORELICK: I’ve never heard that before. Why would they have triedto sue?

JA: Joe Simon claimed that DC was unhappy because The Shieldresembled Superman.

GORELICK: Well, first of all, the original Shield didn’t fly and hadbeen created back in the early 1940s. In fact, he predated CaptainAmerica. So if anyone would have had a gripe, it would have beenMarvel because they had Captain America. Or maybe the other wayaround, because Captain America was a copy of The Shield.

JA: Do you know why Simon and Kirby left The Fly? After all, JoeSimon created the character.

GORELICK: I couldn’t tell you for sure. Simon probably went on toother things that paid him more money. I don’t think Archie paid thatmuch at the time. Plus the fact that the book wasn’t really doing all thatwell.

“The Hangman” Cometh!(But You’ll Have to Read This Whole Interview with Archie Editor

VICTOR GORELICK to Find Out the Secret behind Our Title!)

For some reason, when Archie and the Simon-&-Kirby team got together in1959 to revive The Shield, that June 1959 first issue was titled The Double Life of

Private Strong, and the hero’s everyday identity aped that of Private SteveRogers in the WWII Captain America—a hero who had originally been partly

inspired by The Shield! The Shield splash is repro’d from the 1984 reprint BlueRibbon Comics, Vol. 2, #5. [©2003 Archie Comic Publications, Inc.]

You’ve gotta watch these kids today!Though Archie Andrews had been a featured

character in Pep Comics since his debut in#22 (Dec. 1941), this cover for #35 (Jan. ‘43)is the first on which he appeared along with

usual cover stars The Shield and TheHangman. Archie popped up again on Pep#41 and on every cover thereafter, and by#48 had taken over the covers completely,

with The Shield reduced to a small insetpicture in an upper corner. Pesky teenagers!

[©2003 Archie Comic Publications, Inc.]

42 Victor Gorelick

JA: They seemed to change the concept, because Tommy Troy wasoriginally a kid who finds a magic ring and turns into the adult Fly.Without explanation, Troy becomes an adult.

GORELICK: I’m sure that, in order to drive the sales up, the publishersmade a lot of changes. But I didn’t have any input. My job was artproduction, tracking the artwork, preparing schedules, and workingwith the engraver and printer.

JA: In 1961 they launched The Adventures of The Jaguar comic book,so the changes must have worked.

GORELICK: Archie wanted to stay in the super-hero market andMarvel was starting to move up, so we needed more characters.

JA: When did you go into the service?

GORELICK: I was on active duty in Navy from 1960 to 1963. I was inboot camp the previous summer, so I was out of the office for eightweeks or so. I was supposed to go with the fleet for two years but endedup at Floyd Bennett Field in Brooklyn because they were short-handed.I told Richard that if I was stationed in New York, I’d have to serve anextra year and would be able to do freelance work and fill in onvacations. Richard gave me the okay. For those three years, I was onactive duty as a station-keeper.

I was doing a lot of freelance coloring for Archie at that time andworked at the office on my days off. And all my days off were duringthe week. I handled production work in the office during that time. Ihad thirty days’ leave, so if anyone went on vacation, I’d fill in.

JA: How involved was Richard Goldwater with those books?

GORELICK: He worked with the writers and handed out the assign-ments. Jerry Siegel and Bob Bernstein were doing the writing, but Siegelwas the only guy I met. Siegel worked directly with them but I only hadcontact with the guys doing the artwork, because that was part of myjob.

I think the Archie offices were still on Church Street in New York.Paul Reinman came on boardand started doing super-herowork, too. John Goldwatercame up with a lot of the ideasfor the heroes. Marvel’s Spider-Man had gotten popular, andwe changed the characters tocompete with them. JohnGoldwater had a lot of inputwith how we did the covers andwas particular about what hewanted to see. He wanted us tofollow the Marvel style.

Siegel and Bernstein werevery good writers, but theycame up with a lot of strangestuff. I remember one story thatJerry Siegel wrote for TheMighty Crusaders. They weretrapped by the villains in acanyon or something, and therewas no way out. They wereabout to meet their doom, andall of a sudden, the Rock Peoplecame out of the dirt and savedThe Mighty Crusaders. Thewriters would write themselvesinto corners like that. A lot of

people look back very fondly at those books, but I thought they werevery wacky.

JA: How did Marvel react to all this?

GORELICK: I don’t think Marvel reacted to us much because we wereno competition for them. We didn’t have any big names working for us(except for Jerry Siegel) like Jack Kirby. They also had Stan Lee, whowas such a great promoter that we couldn’t come close to what Marvelwas doing.

I’ll tell you this. If Marvel went back to the way Stan did thosecharacters, they’d be better off today. While Archie might like to publishsuper-heroes, we could never compete with Stan Lee. He knew how toput out super-hero books, and we knew how to put out teenage booksand still do. They tried to put out humor books and never weresuccessful. Same goes for DC.

JA: When the heroes were changed to resemble the Marvel books, didthat increase sales?

GORELICK: I don’t think so. Not to take anything away from PaulReinman, but everybody looked the same in his work. I think he eveninked some of his own work, too. I was doing most of the coloring onthe books, covers included. I did have a cover idea or two, but even thatwas no big deal. It was mostly just photostatting interior art and usingthat for a cover. The artists submitted roughs for approval first and thenthey drew them. It still works the same way today.

JA: It sounds like you were getting more involved in the editorialend.

GORELICK: You have to understand that Archie operates a lot differ-ently than other companies. At Marvel and DC they have bunches ofeditorial assistants. At Archie Comics a lot of people wear a lot ofdifferent hats. Mostly, my job was in production, but I did get involvedin art direction. Occasionally, I put my two-cents in on a story, butRichard Goldwater really handled that. He bought all the stories andassigned all the artists to the stories. The only time I did any of that waswhen he’d be away.

Victor Gorelick 43

In Pep Comics #1 (Jan. 1940), the Irv Novick-drawn Shield hadindeed looked a lot like a walking (American-flag-derived)shield. To the right is Rich Buckler’s Kirby-derived (and duly

credited) cover for Blue Ribbon!Comics #5 (1984). EveryGolden Age buff should pick up a copy of the 2002 tradepaperback America’s 1st Patriotic Comic Book Hero—TheShield, which reprints, in full color, eight of the hero’s

earliest exploits. [©2003 Archie Comic Publications, Inc.]