Alexia Bilingue (1)

-

Upload

silvina-careto -

Category

Documents

-

view

217 -

download

1

Transcript of Alexia Bilingue (1)

Bilingual alexia and agraphia: A neurolinguistic study

A. Pauranik

Indore, India

Accepted 8 July 2005

Available online 12 September 2005

Background

Group studies in aphasia, alexia, and agraphia are uncommon. Too

many variables or parameters of interest in behavioural sciences make

it difficult to tabulate, analyze, and discuss the results unless one re-

stricts the aims of study to some very specific questions and seeks

observation in a narrow field. However, broad-spectrum group studies

are useful. An overview of clinical spectrum can be sketched. Com-

parisons may be made across selected variables. Exceptional or so-

called deviant observations of single case studies are evened out in

large group studies.

The present study was undertaken with the following aims: (a)

Standardizing and validating a test battery for alexia and agraphia in

Hindi–English bilinguals. (b) Classifying patients into various alexic

syndromes, and then correlating them with aphasic syndromes and

lesion morphology on CT Scan. (c) Comparing reading and writing

performance in Hindi and English.

Methods

We developed, standardized, and used a testing protocol, based on

our Hindi version of BDAE for reading and writing functions in 25

Hindi alexic and agraphic subjects with stroke.

A proforma of reading and writing performances including hand

written output and transcription of verbal utterances was noted on

the standard scoring sheet. Diagnostic labels were attributed ac-

cording to definitions of various syndromes of alexia, agraphia, and

aphasia independent of localizing information from clinical and

imaging sources.

The site and extent of the lesions were evaluated by means of CT

scans, outlined on templates.

Results

The mean age of our 25 patients was 50 years which reflects

the relatively high proportion of younger patients with CVA in

India and developing countries. Age of the patient may have

some bearing upon type of cerebrovascular disorder and type of

alexia.

Eight types of alexia and agraphia syndromes were encountered

heterogeneously and nonspecifically with various aphasia types. Spe-

cific, precise, localized CT scan lesions could not be attributed to with

these syndromes. The impairment patterns were not uniform across

patients even in the same aphasia group. In majority of cases, lexical

and phonological processes were unselectively impaired. However,

most patients were true to their syndrome as described in the literature.

Hindi-English bilinguals made similar errors in both languages and

syndromic classifications were also same.

Many types of dissociation and disconnection were found. Patient

number 12 had semantic alexia without agraphia. Patient number 14

had poor reading, poor oral naming, and transcription but his written

naming and transcription to dictation were exceptionally intact. So his

pathways for visual to motor speech function were destroyed when

conversion from one language to another was needed but his auditory

to motor speech functions were intact. Patient number 21 had syntactic

alexia without agraphia (Table 1).

Patient number 2 had remarkably preserved capacity to tran-

scribe between Roman and Devnagari (for Hindi) scripts in either

direction despite severe deficits in oral spelling, word picture

matching, reading verbs and irregular words, and confrontation

written naming. He made many phonological errors. It appears that

grapheme to phoneme conversion pathways may be preserved in an

isolated manner despite severely disrupted access to phonology as

well as semantics.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that impairments of higher cortical func-

tions like reading and writing may not be correlated to precise

neuro-anatomical structures and aphasic syndromes as is some-

times inferred from single case studies. It also appeared that Indo-

European languages follow similar pathways and rules in brain

and are unlike the dissociation seen for Kanji and Kana in Ja-

panese.

The emergence of various disconnection/dissociation paradigms

does not negate the older paradigms of holism and localizationism. In

fact both have survived in the current latest network theories, which

conceptualize overlapping, parallel modules.

Brain and Language 95 (2005) 241–242

www.elsevier.com/locate/b&l

E-mail address: [email protected].

0093-934X/$ - see front matter � 2005 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.bandl.2005.07.123

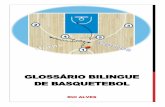

Table 1

Association of Alexia and Agraphia with types of aphasia

Patient numbers and particulars 11 total

1. Semantic alexia with agraphia

Fluent anomic aphasia 3

Wernicke’s aphasia 4

Broca’s aphasia 3

2. Semantic alexia without agraphia 1

Mild Broca’s aphasia 1

3. Semantic alexia with agraphia with some features

of third alexia

1

4. Severe (Anomic) alexia with semantic agraphia 1

Anomic aphasia 1

5. Phonological alexia with agraphia 4

Wernicke’s aphasia 2

Broca’s aphasia 1

Anomic aphasia 1

6. Syntactic alexia with motor agraphia 2

Broca’s aphasia 2

7. Syntactic alexia without agraphia 1

Broca’s aphasia 1

8. Severe alexia with agraphia 2

Global aphasia 2

9. No alexia or agraphia 2

Mild transient Broca’s aphasia 1

Transient aphasia with inability to read or write 1

242 Abstract / Brain and Language 95 (2005) 241–242

![Alexia [reparado]](https://static.fdocuments.net/doc/165x107/55ba47c7bb61eb65438b471e/alexia-reparado.jpg)

![37228519 Feng Shui Alexia Cinzeaca[1]](https://static.fdocuments.net/doc/165x107/55cf9988550346d0339dd750/37228519-feng-shui-alexia-cinzeaca1.jpg)