Alcyone - Nietzsche on Gifts, Noise, And Women by Gary Shapiro

Transcript of Alcyone - Nietzsche on Gifts, Noise, And Women by Gary Shapiro

-

8/10/2019 Alcyone - Nietzsche on Gifts, Noise, And Women by Gary Shapiro

1/4

Review: [untitled]

Author(s): Kathleen Marie HigginsReviewed work(s):Alcyone: Nietzsche on Gifts, Noise, and Women by Gary Shapiro

Source: The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Vol. 50, No. 3 (Summer, 1992), pp. 263-265Published by: Blackwell Publishing on behalf of The American Society for AestheticsStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/431242

Accessed: 04/10/2008 03:52

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless

you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you

may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=black.

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed

page of such transmission.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the

scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that

promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

The American Society for AestheticsandBlackwell Publishingare collaborating with JSTOR to digitize,

preserve and extend access to The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism.

http://www.jstor.org

http://www.jstor.org/stable/431242?origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=blackhttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=blackhttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/stable/431242?origin=JSTOR-pdf -

8/10/2019 Alcyone - Nietzsche on Gifts, Noise, And Women by Gary Shapiro

2/4

Book

Reviews

ook

Reviews

Among

recent

postmodernist

readings

of

art

his-

tory

and

aesthetic

theory,

Roberts's

approach

has the

merit of

advancing

a

strong

characterization f

post-

modern

art. The last

part

of

his book

argues

that the

shift from

modern to

postmodern

art

reduces the

European

raditiono

freely

disposable

material

along-

side other

material,

and it

replaces

he idea of

progress

with an

awarenessof

contingency.

Roberts

elaborates

his

characterization

with elan and

sophistication,

bringing

it

into critical

dialogue

with the

views of

Jean

Baudrillard,

Peter

Burger,

Arthur

Danto,

Jiirgen

Habermas,

and

FredricJameson.

Unlike

Adorno,

whom

he

reads as

pitting

a

pro-

gressive

and

authentic

Schoenbergagainst

a

reaction-

ary

and inauthentic

Stravinsky,

Roberts abandons

he

paradigm

of

progress

that

guides

modernist

aesthet-

ics. In

fact,

he

argues

that both

Schoenberg

and

Stravinskyare postmodern artists who simply give

alternative esponsesto the

situation

of

contingency

broughtabout by

the end of

tradition p. 131).

This

situation,

which renders

modernist

aesthetics inade-

quate, an

aestheticsafter

Adorno

must

understand.

Contingency is a

proteanconcept in

Roberts's

book.

On the one

hand, it contrastswith

the necessity

and

continuity that

Hegel and

Adorno

ascribe

to

the

historical

unfolding of art. On

the other

hand, it

points

to

the

freedom of

postmodern

artists

to

choose

amongvirtually

endless

options unbounded

by

tradi-

tion.

According to

Roberts,

romanticirony in

liter-

ature

prefiguresthe

emancipationof

contingency

inpostmodernart. Afterthe crisis of traditionandthe

shattering of

progress, however,

contingency

be-

comes

systemic. The critique

of

art as arthas

become

intrinsic o

the entire

enterpriseof art

production

and

artreception.This

self-reflection on

the level of

the

system is

a new stage in

the

enlightenment of art

(p.

21).

There is

something odd about

such usage of

terms

like

emancipation,

stage, and

enlightenment.

Their

appealseems to

derive from he

very

paradigm

of

progress

hatRoberts has

abandoned.

Although he

might

esitate to call

postmodern art

better than

modern

art, he at least

suggeststhatpostmodern

art

is

good withinthe largerhistoricalscheme of things.

Yet

I

am unable

o

find

a basis

for

this

suggestion, and

it

is

hard

to

imagine

what the basis

could be, absent

some

latent dea

of

historical

progress.

A

related

puzzle concerns

the

plausibility

of

Rob-

erts's claims about the

enlightened

and

emancipated

character

of

postmodernart. He

says,

for

example,

that the

system

of

art

is

now

enlightened, fully

'rational'and

self-referential,because it is

no longer

blind

to itself

(p.

174).

While this has

some

merits

as

a

claim about art

as an

independent

system,

the

claim

rapidly

oses

plausibility

when one

locates art

at

the intersection of

politics,

economics,

electronic

media, and the culture industry.There art seems in-

Among

recent

postmodernist

readings

of

art

his-

tory

and

aesthetic

theory,

Roberts's

approach

has the

merit of

advancing

a

strong

characterization f

post-

modern

art. The last

part

of

his book

argues

that the

shift from

modern to

postmodern

art

reduces the

European

raditiono

freely

disposable

material

along-

side other

material,

and it

replaces

he idea of

progress

with an

awarenessof

contingency.

Roberts

elaborates

his

characterization

with elan and

sophistication,

bringing

it

into critical

dialogue

with the

views of

Jean

Baudrillard,

Peter

Burger,

Arthur

Danto,

Jiirgen

Habermas,

and

FredricJameson.

Unlike

Adorno,

whom

he

reads as

pitting

a

pro-

gressive

and

authentic

Schoenbergagainst

a

reaction-

ary

and inauthentic

Stravinsky,

Roberts abandons

he

paradigm

of

progress

that

guides

modernist

aesthet-

ics. In

fact,

he

argues

that both

Schoenberg

and

Stravinskyare postmodern artists who simply give

alternative esponsesto the

situation

of

contingency

broughtabout by

the end of

tradition p. 131).

This

situation,

which renders

modernist

aesthetics inade-

quate, an

aestheticsafter

Adorno

must

understand.

Contingency is a

proteanconcept in

Roberts's

book.

On the one

hand, it contrastswith

the necessity

and

continuity that

Hegel and

Adorno

ascribe

to

the

historical

unfolding of art. On

the other

hand, it

points

to

the

freedom of

postmodern

artists

to

choose

amongvirtually

endless

options unbounded

by

tradi-

tion.

According to

Roberts,

romanticirony in

liter-

ature

prefiguresthe

emancipationof

contingency

inpostmodernart. Afterthe crisis of traditionandthe

shattering of

progress, however,

contingency

be-

comes

systemic. The critique

of

art as arthas

become

intrinsic o

the entire

enterpriseof art

production

and

artreception.This

self-reflection on

the level of

the

system is

a new stage in

the

enlightenment of art

(p.

21).

There is

something odd about

such usage of

terms

like

emancipation,

stage, and

enlightenment.

Their

appealseems to

derive from he

very

paradigm

of

progress

hatRoberts has

abandoned.

Although he

might

esitate to call

postmodern art

better than

modern

art, he at least

suggeststhatpostmodern

art

is

good withinthe largerhistoricalscheme of things.

Yet

I

am unable

o

find

a basis

for

this

suggestion, and

it

is

hard

to

imagine

what the basis

could be, absent

some

latent dea

of

historical

progress.

A

related

puzzle concerns

the

plausibility

of

Rob-

erts's claims about the

enlightened

and

emancipated

character

of

postmodernart. He

says,

for

example,

that the

system

of

art

is

now

enlightened, fully

'rational'and

self-referential,because it is

no longer

blind

to itself

(p.

174).

While this has

some

merits

as

a

claim about art

as an

independent

system,

the

claim

rapidly

oses

plausibility

when one

locates art

at

the intersection of

politics,

economics,

electronic

media, and the culture industry.There art seems in-

creasingly

ess

transparent

nd

increasingly

ess like

a

self-contained

system.

Indeed,

one weakness of Roberts'sbook

is that it

pays

too little

regard

o Adorno's

social

theory

and

his

critique

of

the culture

ndustry.

These,

it seems

to

me,

provide

more fruitful sources

for

a

theory

of

post-

modern

art thandoes

Philosophy of

Modern

Music.

At the same

time,

the latter work

can

hardly

be

understood

apart

from its connections

with

Adorno's

contemporaneouswritings

on

fascism,

popular

music,

and the authoritarian

ersonality.

Although

Roberts

touches

on

similar

topics

in

his brief and

suggestive

sections on Jameson

(pp.

104-145)

and

Baudrillard

(pp.

198-207),

he does not

employ many

of the

resources

available in Adorno's version of

critical

theory.

The motivation for

raising

this criticism is not a

devotion to Adornobut a concernforthe directionof

postmodernist

theory. While applauding

Roberts's

creative and

astute

proposals

for

a theory of

post-

modern art, I find

myself wishing for

greaterengage-

ment

with

political,

economic, and broadly

cultural

issues.

For the

crisis of tradition

has not been

limited

to art, and the

emancipation

f contingency

now

pervades the

entire culture of

late

capitalism.

Moreover,

the significance

of these

developments

depends on

larger

movements toward

freedom

and

justice and

peace thanthe

arts as such can

provide. It

was precisely

such

movements, orthe

obstructions o

them, that

Adorno tried to

disclose in the

art and

cultureof his time. Theirdisclosure in our time is a

challenge

facing anytheory

afterAdorno.

LAMBERT

ZUIDERVAART

Department

of Philosophy

Calvin

College

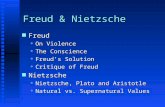

SHAPIRO, GARY.

Alcvone:

Nietzscheon

Gifts,

Noise, and Women.

SUNY

Press, 1991,

158

pp.,

$39.50 cloth,

$12.95 paper.

Gary Shapiro

sets out to

reread Nietzsche's Thus

Spoke Zarathustrain terms of what Nietzsche de-

scribed as its

halcyon tone.

Shapirounpacks this

expression in

terms of the

myth

of

Alcyone, who,

while

lamenting her

husband's death at

sea, was

turned

along with her

husband nto

sea birds ( hal-

cyons ) by

the gods.

Shapirolinks the

cries

of Al-

cyone

to the primordial

ries and concerns of

women,

cries

and concerns

displaced by the Western

meta-

physicaltradition.

Nietzsche's

remark bout he hal-

cyon

tone of

Zarathustraheraldsthe returnof

such

repressed

concerns, among

them the topics

of

gifts,

noise, and

women.

In

the first essay, On

Presents and

Presence,

Shapirolinks Nietzsche's emphasison gift-giving in

creasingly

ess

transparent

nd

increasingly

ess like

a

self-contained

system.

Indeed,

one weakness of Roberts'sbook

is that it

pays

too little

regard

o Adorno's

social

theory

and

his

critique

of

the culture

ndustry.

These,

it seems

to

me,

provide

more fruitful sources

for

a

theory

of

post-

modern

art thandoes

Philosophy of

Modern

Music.

At the same

time,

the latter work

can

hardly

be

understood

apart

from its connections

with

Adorno's

contemporaneouswritings

on

fascism,

popular

music,

and the authoritarian

ersonality.

Although

Roberts

touches

on

similar

topics

in

his brief and

suggestive

sections on Jameson

(pp.

104-145)

and

Baudrillard

(pp.

198-207),

he does not

employ many

of the

resources

available in Adorno's version of

critical

theory.

The motivation for

raising

this criticism is not a

devotion to Adornobut a concernforthe directionof

postmodernist

theory. While applauding

Roberts's

creative and

astute

proposals

for

a theory of

post-

modern art, I find

myself wishing for

greaterengage-

ment

with

political,

economic, and broadly

cultural

issues.

For the

crisis of tradition

has not been

limited

to art, and the

emancipation

f contingency

now

pervades the

entire culture of

late

capitalism.

Moreover,

the significance

of these

developments

depends on

larger

movements toward

freedom

and

justice and

peace thanthe

arts as such can

provide. It

was precisely

such

movements, orthe

obstructions o

them, that

Adorno tried to

disclose in the

art and

cultureof his time. Theirdisclosure in our time is a

challenge

facing anytheory

afterAdorno.

LAMBERT

ZUIDERVAART

Department

of Philosophy

Calvin

College

SHAPIRO, GARY.

Alcvone:

Nietzscheon

Gifts,

Noise, and Women.

SUNY

Press, 1991,

158

pp.,

$39.50 cloth,

$12.95 paper.

Gary Shapiro

sets out to

reread Nietzsche's Thus

Spoke Zarathustrain terms of what Nietzsche de-

scribed as its

halcyon tone.

Shapirounpacks this

expression in

terms of the

myth

of

Alcyone, who,

while

lamenting her

husband's death at

sea, was

turned

along with her

husband nto

sea birds ( hal-

cyons ) by

the gods.

Shapirolinks the

cries

of Al-

cyone

to the primordial

ries and concerns of

women,

cries

and concerns

displaced by the Western

meta-

physicaltradition.

Nietzsche's

remark bout he hal-

cyon

tone of

Zarathustraheraldsthe returnof

such

repressed

concerns, among

them the topics

of

gifts,

noise, and

women.

In

the first essay, On

Presents and

Presence,

Shapirolinks Nietzsche's emphasison gift-giving in

26363

-

8/10/2019 Alcyone - Nietzsche on Gifts, Noise, And Women by Gary Shapiro

3/4

The Journal of Aesthetics and Art

Criticism

Zarathustra

with

(alleged)

abandonmentf themeta-

physics

of

presence.

Given our

metaphysical

and

economic

history,

Shapiro

contends,

we

tend

to

inter-

pret

the

given

(the

es

gibt

in

German),

and

our

relationship

o

it,

in

terms

of

relatively

static

conven-

tions of

privateproperty.

The

given

is

clear-cut,

as

is its

significance.

In

emphasizing

he activitiesasso-

ciated with

gifts,

the

uncanny

other

of

property,

Nietzsche draws attention to the

dynamics

of ex-

change

and

reinterpretation

f

the

participants'

roles

thatresults.

In

preferring

heeconomic model

of

giving

gifts

to

that

suggested by

the modern

marketplace,

Nietzsche

indicates that

the identities of

persons

and of the

given

in

general

are

subject

to

on-going renegotia-

tion

and

hermeneutic

interpretation. Shapiro

con-

cludes from this

that,

contrary

to

Heidegger's

read-

ing

of Nietzsche as

the West's last

metaphysician,

Nietzsche is already

nvolved n explodingtraditional

metaphysical categories. Valuation itself is

trans-

valued n Zarathustra'selebrationof the

gift-giving

virtue. On

this model, the meaningof what is

given

is constantly n flux.

Shapiro'sapproach s more suggestiveand

imagis-

tic than exhaustive in its pursuitof particular

nter-

pretive hints. Shapiro'sorientation s wedded to

that

of certain recent

French interpretersof

Nietzsche,

particularlyDerrida.

Shapiro'splayful

appropriation

of wordsand their senses, as well as his avoidance

of

dogged argumentation

n favorof a style moreakin

to

reverie,will be familiar o those versed n the worksof

Derridaand his

proponents.

However,Shapiroalso assumesthathis audience

is

well-versed n French iterarycriticism and its

lingo;

and he makes

little effort to assist those who

are not.

Moredisturbing roma philosophicalpoint of view

is

the fact thatShapirooften assumesconclusions

drawn

by Derrida,

Michel Serres, George Batailleand

oth-

ers without offering reasons why the reader

should

accept them. This reliance on French critics,

besides

leaving many readers unpersuaded, s likely to

ob-

scure the originalityof many of Shapiro's

nsights.

Shapiro's econd essay, Parasites nd

theirNoise,

for example, provides a refeshing look at Zara-

thustra, Part IV, affordedby focusing on its

abun-

dance of noise descriptions

and animal imagery.

Shapiro artfully indicates the many ways that

the

motifs of noises and interruption

re employed in

the

text, and he argues convincingly that

Nietzsche's

manipulations

f these motifs should lead to

reversals

of their significance. Zarathustra'swork, for

exam-

ple, is enhanced by the interruptions

hat initially

forestalled

t.

Shapiro analyses the reversals

involved in Zara-

thustra, PartIV, in terms

of the image of the parasite.

Drawing on Zarathustra'srequentcomplaints

about

parasites and the higher men's parasitic behavior,

Shapiro

contendsthat Part IV

is

an

allegory

of

the

parasite p.

62)

that

portrays

parasitism

as

complex

and

completely

transitive

(p.

88).

Zarathustra s

parasitic

on his own

parasites,

and

ultimately

the

whole relation

of

parasitism

becomes

undecidable

(p.

100).

The

least

convincing

aspect

of this

reading

is

Shapiro's mportation

of Serres'sviews

on

parasites.

Relying

on

Serres's contention that

parasitism

(not

predation)

is basic to animal and human

relations,

Shapirosuggests

thatZarathustra

presentsparasitism

as a basic and

mutually

beneficial mode of

human

interaction.

Again, Shapiro

sees

Zarathustra

s

de-

picting

human

exchange

and

reversing

he

traditional

perspective

on it.

Most

likely,

Shapiro

is able

to

see

so

much

evi-

dence that Nietzsche

is

transvaluingparasitism

be-

cause he has an

extremely

broad

conception

of

what

the expression parasite

means. At times,

it

seems

to mean nothing more than

the

mutually

dependent

and symbiotic (p. 67). Shapiro

also is

evidently

quite comfortable with the current

literary

critical

usage of the term, for he

notes that

Zarathustra,

Part

IV, has often been read as parasitic on

the

first

three parts of the work. Following Serres,

Shapiro

also links severalother senses of the term:

the

biolog-

ical sense of the animalwho feeds on but

does

not kill

another animal; the economic

sense of

human

be-

ings who profit, similarly, rom others ;and

the

sense

prevalent

n

French

and other romance

languagesof

static or noisy interference

(p. 62).

Shapirogoes

on to claim that Nietzsche intendedat

least

these last

three senses of parasitism n his writing:

Following

Michel Serres in The Parasite I want to

demonstrate

that Nietzsche saw these apparentlydiverse

senses as

partof a system (p.

63).

Granted,Nietzsche does at times

refer

to

the

same

people as noisy and as parasites.

But the

overtones

of the French term

are not obviously

basic

to

his

conception of its German translation.

Nevertheless,

Shapirotakes the interruptions

nd

noises

of

Part

IV

as indicationsof Nietzsche's concern

with

parasitism

as such. The several moments in which

Zarathustra

returns rom catchinga breathof air and nterrupts he

higher men's activities are readas scenes

in

which

he

is cast in the role of a parasite (albeit

possibly

a

medicinal

one) (p. 61). The

appearances

of

ani-

mals and animal sounds are

also

treated

as

hints

regardingparasitism;

and Zarathustra's

omplex

rela-

tionships with animals are, accordingly,

interpreted

as indicationsof the complexity

of the

parasite

rela-

tionship. Such moves are at least

methodologically

questionable.

Even more questionable-as well as

startling-is

the suggestion of Alcyone's

song,

Shapiro's

third

essay:

Is the mouth of Thus Spoke

Zarathustra

he

mouth of a woman? (p. 122). Shapirostresses that

264

-

8/10/2019 Alcyone - Nietzsche on Gifts, Noise, And Women by Gary Shapiro

4/4