AFS AFS ––– Advanc Advanc Advances in Food Scienceses in ...

Transcript of AFS AFS ––– Advanc Advanc Advances in Food Scienceses in ...

AFS AFS AFS AFS –––– Advanc Advanc Advanc Advances in Food Scienceses in Food Scienceses in Food Scienceses in Food SciencesContinuation of CMTL founded by F. Drawert

Production by PSP – Parlar Scientific Publications, Angerstr. 12, 85354 Freising, Germany in cooperation with Lehrstuhl für Chemisch-Technische Analyse und Lebensmitteltechnologie,

Technische Universität München, 85350 Freising - Weihenstephan, Germany

Copyright © by PSP – Parlar Scientific Publications, Angerstr. 12, 85354 Freising, Germany. All rights are reserved, especially the right to translate into foreign language. No part of the journal

may be reproduced in any form- through photocopying, microfilming or other processes- or converted to a machine language, especially for data processing equipment- without the written permission of the publisher.

The rights of reproduction by lecture, radio and television transmission, magnetic sound recording or similar means are also reserved.

Printed in GERMANY Printed in GERMANY Printed in GERMANY Printed in GERMANY –––– ISSN 1431 ISSN 1431 ISSN 1431 ISSN 1431----7737773777377737

© by PSP Volume 24 – No 3. 2002 Advances in Food Sciences

2

AFSAFSAFSAFS---- Editorial Board Editorial Board Editorial Board Editorial Board

Chief Editors: Chief Editors: Chief Editors: Chief Editors:

Prof. Dr. H. Parlar Institut für Lebensmitteltechnologie und Analytische Chemie, TU München -

85350 Freising-Weihenstephan, Germany - E-mail: [email protected]

Dr. G. Leupold Institut für Lebensmitteltechnologie und Analytische Chemie, TU München -

85350 Freising-Weihenstephan, Germany - E-mail: [email protected]

CoCoCoCo----EEEEditor:ditor:ditor:ditor:

Prof. Dr. R. G. Berger Zentrum Angewandte Chemie, Institut für Lebensmittelchemie, Universität Hannover

Wunstorfer Straße 14, 30453 Hannover - E-mail: [email protected]

AFSAFSAFSAFS- Advisory BoardAdvisory BoardAdvisory BoardAdvisory Board

E. Anklam, I M. Bahadir, D F. Coulston, USA J.M. de Man, CAN N. Fischer, D S. Gäb, D A. Görg, D U. Gill, CAN D. Hainzl, P W.P. Hammes, D D. Kotzias, I F. Korte, D M.G. Lindhauer, D B. Luckas, D S. Nitz, D A.M Raichlmayr-Lais, D M. Spiteller, D H. Steinhart, D R.F. Vogel, D R.P. Wallnöfer, D P. Werkhoff, D

Editorial ChiefEditorial ChiefEditorial ChiefEditorial Chief----Officer:Officer:Officer:Officer:

Selma Parlar PSP- Parlar Scientific Publications - Angerstr.12, 85354 Freising, Germany E-Mail: [email protected] - www.psp-parlar.de

Marketing Chief Manager:Marketing Chief Manager:Marketing Chief Manager:Marketing Chief Manager:

Max-Josef Kirchmaier MASELL-Agency for Marketing & Communication, Public-Relations Angerstr.12, 85354 Freising, Germany E-Mail: [email protected] - www.masell.com

© by PSP Volume 24 – No 3. 2002 Advances in Food Sciences

93

CONTENTS ORIGINAL PAPERS

EFFECTS OF STERILANTS ON GROWTH OF Pleurotus Sajor-Caju ON CASSAVA PEELS 94 C.O. Adenipekun and I. O Fasidi ANTIOXIDANT PROPERTIES OF OLIVE PHENOLIC COMPOUNDS 99 ON SUNFLOWER OIL STABILITY R. S Farag, N. M. Abd-Elmoien and E. A. Mahmoud GLYKOSIDISCH GEBUNDENE AROMASTOFFE IN HOPFEN (Humulus lupulus L.): 106 1. ENZYMATISCHE FREISETZUNG VON AGLYCONEN H. Kollmannsberger und S. Nitz

MICROBIAL AND BIOCHEMICAL CHANGES OCCURRING DURING 116 FERMENTATION OF marula (Sclerocarya birrea subspecies caffra) JUICE TO PRODUCE mukumbi, A TRADITIONAL ZIMBABWEAN WINE A. Mpofu and R. Zvauya COMPARATIVE STUDIES ON BIOSORPTION OF COBALT (II), NICKEL (II), 121 LEAD (II) AND MANGANESE (II) BY FOUR DIFFERENT FUNGI M. H. Habibi, G. Emtiazi, Z. Khalesi and M. A. Haghighipour

SHORT COMMUNICATION

PHYSICOCHEMICAL ANALYSIS OF TOKAT REGION (TURKEY) HONEYS 125 M. Tüzen

BOOK REVIEWS � BÜCHERSCHAU 128 G. Leupold INDEX 135

© by PSP Volume 24 – No 3. 2002 Advances in Food Sciences

94

EFFECTS OF STERILANTS ON GROWTH OF Pleurotus Sajor-Caju ON CASSAVA PEELS

C.O. Adenipekun and I. O Fasidi

Department of Botany and Microbiology, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria

SUMMARY

The addition of 0.5% formalin as sterilant resulted in the best mycelial growth of Pleurotus sajor-caju on cas-sava peel wastes and also served as a good biocide in reducing the rate of contamination by other microorgan-isms. In all the series of experiments, in which calcium sulphate, calcium carbonate, ammonium nitrate, ammo-nium sulphate and urea were added, the fungus exhibited the best mycelial growth on the substrates containing 0.1% (w/v) of the salts, except for calcium carbonate, where the best growth was attained only by addition of 1.0% (w/v).

However, the addition of ammonium salts resulted in a decrease of mycelial growth with an increase in the salt concentration. A mixture of various proportions of CaSO4 and CaCO3 to the substrate produced no significant ef-fects on the growth of the fungus. It was also observed that the addition of the insecticide Rogor L 40 and fungi-cide Brestan in concentrations of 0.5%, 1.0% and 2.0% had highly significant inhibitory effects on growth.

KEYWORDS: Pleurotus sajor-caju, cassava peels, fungicides, insecticides.

INTRODUCTION

In Nigeria mushrooms are eaten generally because of their desirable flavour and food values. Kadiri and Fasidi [1] have shown that P. tuber-regium is highly nutritive and very rich in proteins but also in sugars such as galactose. They are also consumed in various combinations of me-dicinal herbs and other ingredients with the intention to cure headache, stomach ailments, colds and fever as well as asthma, smallpox and high blood pressure [2, 3].

The cultivation of Pleurotus species on tree stumps

and logs was first described by Falck [4]. Lozovoi [5] conducted a study on Pleurotus ostreatus and other Pleuro-tus strains and found that the recommended substrate for

cultivation consisted of sawdust (73-76%), chalk (1-2%), carbamide (0.3-0.5%), NPK (0.3 � 0.5%) and water (2.0 � 2.5%).

Recent studies show that Pleurotus species can be cultivated on sterilized straw compost [6]. Fasidi and Kadiri [7] found that Lentinus subnudus, a Nigerian edi-ble mushroom grew best on Andropogan tectorum (Poaceae) straw supplemented with 30% rice bran or milled cassava peels. Fructification also occurred on logs of Spondias mombin and unfermented compost compris-ing straw, rice bran, horse dung and CaSO4.

In Nigeria, cassava peels are one of the important wastes generated during the processing of cassava for garri production. It is proposed to crush the peels and allow this to ferment with the liquid squeezed out from the cassava mash (second waste in garri production) hav-ing microorganisms capable of hydrolyzing the gluco-sides. The resulting product is dried and used as animal feed. But if it will be useful as a substrate, then this will be a direct way of cleaning the environment. Pleurotus sajor-caju is an exotic and highly nutritive species and its cultivation should be encouraged to supplement the pro-tein requirements of Nigerians. To guarantee optimal mycelial growth, also formalin was used as a sterilant, because there are no up-to-date decrees or legislative regulations concerning its use in food production. This study, therefore, aims at investigating the growth of the oyster mushroom using cassava peels, an agricultural waste, as the main substrate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The pure culture of Pleurotus sajor-caju was ob-tained from I. O. Fasidi, Department of Botany and Mi-crobiology at the University of Ibadan. Fresh cultures were got by regular subculturing on potato dextrose agar medium.

Cassava peels were collected fresh from the cassava flour mill at Abadina, University of Ibadan, sun-dried for

© by PSP Volume 24 – No 3. 2002 Advances in Food Sciences

95

a period of one hour and then macerated in a laboratory mill into particles of about 5 mm in diameter.

Effects of sterilants

The effect of some sterilants on the rates of contami-nation and growth of P. sajor-caju mycelia on cassava peel substrate was determined. The sterilants Chlorox and for-malin were prepared in different concentrations (Chlorox, 10% and 20% (v/v); formalin, 0.5%, 1.0% and 2.0% (v/v)). 15 g of ground cassava peels were weighed into each petri dish containing 10 ml of sterilant solution. Then the mix-ture was stirred until the substrates were well-moistened. The plates were then cooked at 100 °C for a period of one hour in a waterbath and steam-sterilized in an autoclave at 121 °C for 30 min or left on the bench unsterilized.

Effect of biocides

Two fungicides, Benlate and Brestan, an insecticide roger 40 and sterilants fermalin and Aldrex T were pre-pared in different concentrations � 0.5%, 1.0% and 2.0%. For Benlate solution, 10ml of absoluten alcohol was added to dissolve the powder and the volume was made up to 100ml with sterile distilled water. Fifteen grammes of ground cassava peels were weighed into each isolate; 10ml of sterilant solution was pipetted into each plates the mixture was well stirred so that the substrate is well soaked.

Effect of additives

The effect of some mineral salts (calcium sulphate, calcium carbonate, ammonium nitrate ammonium sul-phate and urea) as additives on the rate of mycelial growth on cassava peels was investigated. These salts

were prepared in various concentrations, 0.1%, 0.5%, 1.0% and 2.0% (w/v).

15 g of ground cassava peels were weighed into each petri dish, followed by addition of 10 ml of salt solution with different concentrations and, finally, mixed thor-oughly with the cassava peels as substrate.

Also the effect of a mixture of two mineral salts, cal-cium carbonate and calcium sulphate, on the mycelial growth of the fungus was tested. A fixed concentration of CaSO4 (0.2%) with varying amounts of CaCO3 (0.2%, 0.4%, 2.0% and 4.0% w/v) was used. Into each petri dish containing 15 g of ground cassava peels, 5 ml of 0.2% CaSO4 (w/v) was pipetted, followed by the addi-tion of 5 ml each of the CaCO3 solutions in different concentrations. Afterwards the solutions were mixed thoroughly with the cassava peels.

In the set-up, 10 ml distilled water served as control solution and each treatment was carried out in triplicate. The petri dishes were wrapped with aluminium foil and autoclaved at 121 °C for 30 min. After cooling each of the substrates was inoculated in the centre with an agar plug (0.7 mm) obtained from a 7-day old pure culture of Pleu-rotus sajor-caju by means of a sterile cork borer. These sets of plates were then incubated at 30 ± 2 °C and read-ings of linear growth of mycelia on each plate were taken at 2-day intervals for a period of 8 days except for the experiments with biocides where readings were taken daily for a period of 7 days.

The ANOVA test was used to determine the effect of the treatments on the growth of mycelia of the fungus (P < 0.05 and P<0.01). The data were further analyzed using the LSD test at (P<0.05 and P<0.01).

TABLE 1 - Effectiveness of different methods of sterilization on rates of mycelial growth of Pleurotus sajor-caju

Substrates Diameter of mycelial growth (mm) CP + water + autoclaving (control) 6.38 ± 0.32 CP + 10% chlorox and autoclaving 5.40 ± 0.65 ns CP + 10% chlorox and cooking 6.38 ± 0.38 ns CP + 10% chlorox and left unsterilized C CP + 20% chlorox and autoclaving 5.25 ± 0.25ns CP + 20% chlorox and cooking 4.63 ± 0.88ns CP + 20% chlorox and left unsterilzed C CP + 0.5% formalin and autoclaving 6.65 ± 0.20ns CP + 0.5% formalin and cooking C CP + 0.5% formalin and left unsterilized C CP + 1.0% formalin and autoclaving 4.28 ± 0.15ns CP + 1.0% formalin and cooking C CP + 1.0% formalin and left unsterilized C CP + 2.0% formalin and autoclaving 4.23 ± 0.13ns CP + 2.0% formalin and cooking 0.70 ± 0.00 CP + 2.0% formalin and left unsterilized C

Each figure is a mean of 3 readings ± standard error taken on 8th day. CP = cassava peels; C = No growth recorded due to contamination; ns = values not significant (P < 0.05, P < 0.001) by LSD test; * = Significant (P<0.05) by LSD test; ** = Highly significant at (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01) by LSD test.

© by PSP Volume 24 – No 3. 2002 Advances in Food Sciences

96

TABLE 2 - Effect of some biocides on mycelial growth of Pleurotus. sajor – caju on cassava peels.

Substrates Diameter of mycelial growth (mm) CP + water (control) 5.50 ± 0.06 CP + 0.5% Aldrex T 5.05 ± 0.19ns CP + 1.0% Aldrex T 5.55 ± 0.00ns CP + 2.0% Aldrex T 4.85 ± 0.08ns CP + 0.5% Benlate 1.70 ± 0.10** CP + 1.0% Benlate 2.87 ± 0.13** CP + 2.0% Benlate 1.78 ± 0.46** CP + 0.5 % Brestan concn 4.80 ± 0.46ns CP + 1.0% Brestan concn. 4.75 ± 0.13ns CP + 2.0% Brestan concn 3.50 ± 0.06** CP + 0.5% formalin 6.18 ± 0.09** CP + 1.0% formalin 4.50 ± 0.00* CP + 2.0% formalin 0.70 ± 0.00** CP + 0.5% Rogor 40 4.25 ± 0.25** CP + 1.0% Rogor 40 3.22 ± 0.53** CP + 2.0% Rogor 40 1.69 ± 0.14**

Each figure is a mean of 3 readings ± standard error taken on 7th day. CP = cassava peels; ns = values not significant (P < 0.05, P < 0.001) by LSD test. * = Significant (P<0.05) by LSD test; ** = Highly significant at (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01) by LSD test.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In all the substrates to which sterilants (Chlorox or formalin) were added followed by antoclaving, good myce-lial growth was observed, even in the control, but the un-sterilized substrate resulted in a serious culture contamina-tion (Table 1). The LSD test showed no significant differ-ence (P < 0.05 and P< 0.01) between control and all treat-ments except that of 2.0% formalin and cooking. Pizer [8] reported that steam sterilization for one hour at 20 lbs pres-sure prior to inoculation with spawn, altered the physical nature of the composts by dispersing starch and also brought about coagulation of proteins. He also found that the effect of sterilization on mycelial growth of fungus was dependent on the nature of the compost, the previous treatment and time of sterilization. Pleurotus sajor-caju exhibited lower mycelial growth on most of the substrates, to which biocides were added, compared to the control (Table 1). Better mycelial growth, however, was recorded on substrates to which 1.0% Aldrex T and 0.5% formalin were added, the latter stimulating better growth (Table 2). Lowest mycelial growth was recorded at 2.0% concentra-tions of the biocides with the lowest growth rate for forma-lin. Benlate and Rogor 40 at all concentrations had a highly significant effect (P<0.01) on mycelial growth, the former being a fungicide and the latter an insecticide. Brestan only recorded a highly significant effect (P≤ 0.05) at 2.0% (w/v), possibly its most efficacious concentration.

Formalin had highly significant effects (P ≤ 0.05) at concentrations of 0.5% and 2.0% (v/v). The low concen-tration coupled with autoclaving might have provided a selective substrate favourable for mycelia and other con-

taminations. This is in agreement with findings of Gen-ders [9] who used formalin as a sterilant before and dur-ing the process of composting either to prevent the spread of brown plaster mould or to sterilize soil sometimes used for casing where sterilization equipments are not avail-able. In the series of experiments, when CaSO4, CaCO3, NH4NO3, (NH4)2SO4 and urea were added, the fungus showed the best mycelial growth on the substrate to which 0.1% (w/v) concentration of the salts was added, except CaCO3, where optimal growth was achieved at a concentration of 1.0% (Table 3).

Duggar [10] found in his experiments that some slight advantages resulted from the inclusion of calcium com-pounds. Pizer and Thompson [11] suggested that the addi-tion of small amounts (0.5 parts of calcium per 100 parts of dry compost) flocculated the manure and that this was the most suitable for rapid, vigorous growth. Calcium has also been found to be an indispensable nutrient, since it is physiologically antagonistic to potassium and magnesium and also overcomes the inhibitory effect of these elements on the growth of the mycelium [12]. Calcium sulphate (gypsum) is a �conditioner� or �fertilizer�, which improves the yield of mushrooms when cultivated in the laboratory and on commercial basis, because of its indirect activity by improving conditioning of manure compost overcom-ing greasiness, excessive moisture, excess ammonia and excess alkalinity [13]. CaCO3 has been found to be less effective at concentrations of 0.1% and 0.5% (w/v), probably due to its low solubility under alkaline condi-tions or possibly that alkali carbonate is formed by base exchange, increased pH and had a detrimental effect on the structure of the mature culture [10]. Calcium has also been used to adjust the levels of pH between 7 and 8 [13].

© by PSP Volume 24 – No 3. 2002 Advances in Food Sciences

97

TABLE 3 - Effect of additives on mycelial growth of P. sajor. caju on cassava peels.

Substrates Diameter of mycelial growth (mm) CP + water (control) 6.00 ± 0.00 CP + 0.1% CaSO4 6.60 ± 0.20ns CP + 0.5 % CaSO4 5.92 ± 0.69ns CP + 1.0% CaSO4 4.63 ± 0.10* CP + 2.0% CaSO4 4.63 ± 0.10* CP + 0.1% CaCO3 6.52 ± 0.76ns CP + 0.5% CaCO3 5.77 ± 0.02ns CP + 1.0% CaCO3 7.07 ± 0.44* CP + 2.0% CaCO3 6.08 ± 0.08ns CP + 0.1% NH4NO3 6.75 ± 0.75ns CP + 0.5% NH4NO3 4.60 ± 0.40** CP + 1.0% NH4NO3 4.51 ± 0.06** CP + 2.0% NH4NO3 5.14 + 0.39ns CP + 0.1% (NH4)2SO4 7.75 ± 0.25** CP + 0.5% (NH4)2SO4 6.25 ± 0.05ns CP + 1.0% (NH4)2SO4 4.91 ± 0.05* CP + 2.0% (NH4)SO4 4.45 ± 0.20** CP + 0.1% urea 6.48 ± 0.38ns CP + 0.5% urea 6.28 ± 0.53ns CP + 1.0% urea 5.60 ± 0.10ns CP + 2.0% urea 5.30 ± 0.30ns

Each figure is a mean of 3 readings ± standard error taken on 8th day. ns = values not significant (P < 0.05, P < 0.001) by LSD test * = Significant (P<0.05) by LSD test; ** = Highly significant at (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01) by LSD test.

Duggar [10] found in his experiments that some slight

advantages resulted from the inclusion of calcium com-pounds. Pizer and Thompson [11] suggested that the addi-tion of small amounts (0.5 parts of calcium per 100 parts of dry compost) flocculated the manure and that this was the most suitable for rapid, vigorous growth. Calcium has also been found to be an indispensable nutrient, since it is physiologically antagonistic to potassium and magnesium and also overcomes the inhibitory effect of these elements on the growth of the mycelium [12]. Calcium sulphate (gypsum) is a �conditioner� or �fertilizer�, which improves the yield of mushrooms when cultivated in the laboratory and on commercial basis, because of its indirect activity by improving conditioning of manure compost overcom-ing greasiness, excessive moisture, excess ammonia and excess alkalinity [13]. CaCO3 has been found to be less effective at concentrations of 0.1% and 0.5% (w/v), probably due to its low solubility under alkaline condi-tions or possibly that alkali carbonate is formed by base exchange, increased pH and had a detrimental effect on the structure of the mature culture [10]. Calcium has also been used to adjust the levels of pH between 7 and 8 [13].

The addition of ammonium salts at 0.1% (w/v) levels resulted in better mycelial growth, compared to the control. Styer [14] reported ammonium salts as useful sources of nitrogen, the most complex being the most effective. A decrease in mycelial growth of the fungus with increase in the concentration of salts was also observed. This might be

due to the fact that mushroom mycelium is high in nitrogen (6.44% of its dry weight) with nearly half of this nitrogen in a water-soluble form and that ammonium salts of strong acids soon develop a highly acidic substratum that the my-celium is inhibited and eventually killed [15]. Zadrazil [16] recorded that inorganic nitrogen (e.g. ammonium nitrate) increases the yield of fruit bodies by about 30%. Addition of urea at all concentrations had no significant effect on growth of the fungus. This is in contrast to the findings of Styer [14] who reported that urea has been recognized as a utilizable nitrogen source and is sometimes more suitable than amino-acids in certain edible mushrooms.

Pleurotus sajor-caju showed better mycelial growth than the control on all the substrates to which a mixture of mineral salts was added. No significant difference (P<0.05, P<0.01) was observed when the individual treatments were compared with the control by means of the LSD test.

From these results it is clear that P. sajor-caju, an ex-otic species, can be cultivated in the tropical laboratory or in large quantities in the field on composts of cassava peels with 0.1% (w/v) of calcium sulphate, ammonium nitrate, ammonium sulphate, urea and 1.0% of calcium carbonate. The addition of biocides such as formalin at 0.5% as a sterilant followed by autoclaving to reduce the high rate of contamination by other fungi and microorgan-isms will ultimately result in better fruit body production of P. sajor-caju on cassava peels.

© by PSP Volume 24 – No 3. 2002 Advances in Food Sciences

98

TABLE 4 - Effect of a mixture of additives on growth of P. sajor-caju on cassava peels.

Substrates Diameter of mycelial growth (mm) CP + water (Control) 4.88 ± 0.19 CP + 0.2% CaS04 + 0.2% CaC03 4.88 ± 0.38ns CP + 0.2% CaS04 + 1.0% CaC03 5.10 ± 0.10ns CP + 0.2% CaS04 + 2.0% CaCo3 5.32 ± 0.20ns CP + 0.2% CaS04 + 4.0% Cac03 5.0 ± 0.29ns

Each figure is a mean of 3 readings ± standard error taken on 8th day. ns = values not significant (P < 0.05, P < 0.001) by LSD test.

REFERENCES

[1] Kadiri; M. and Fasidi, I. O. (1990a). Nig. J. Sci 24: 86 � 9.

[2] Oso, B. A. (1977). Mycologia 69 (2): 271-279.

[3] Fasidi, Isola O. and Olorunmaiye, Kehinde S. (1994). Food Chem. 50, 397-401.

[4] Falck, R. (1917). Z. forst. Jagdires 4: 159 � 165.

[5] Lozovoi, V. D. (1980). Rastit Resur 16 (1): 38 � 45.

[6] Chandrashekar, Y. R.; Bano, Z. and Rajarathnan, S. (1981). Trans Brit. Mycol. Soc. 77 (3): 491 � 495.

[7] Fasidi, I. O. and Kadiri, M. (1993). Rev. Biol. Trop. 4(3): 411 � 415.

[8] Pizer, N. H. (1937). J. Agric Sci. 27: 349 � 376.

[9] Genders, R. (1982). Mushroom growing for everyone. Ist ed. Faber and Faber publication 115pp.

[10] Duggar, B. M. (1905). U.S. Dept. Agr. Bur. Pl. Ind. Bull. 85: 1 � 60.

[11] Pizer, N. H. and Thompson, A. J. (1938). J. Agric Sc. 28: 604 � 617.

[12] Treschow, C. (1944). Dansk. Botanisk Arkiv. 11: 1 � 180.

[13] Singer, R. C. (1961). Mushrooms and Truffles. Botany cultiva-tion and utilization. World crops books 1st ed. interscience pub-lishers (nc 272 pp).

[14] Styer, J. F. (1928). Amer. J. Bot. 15: 246 � 250.

[15] Waksman and Nissen, W. (1932). Amer. J. Bot. 19: 514 � 537.

[16] Zadrazil, F. (1980). Eur. J. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnicol 9: 31 � 35.

Received for publication: March 14, 2002 Accepted for publication: September 10, 2002 CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

C.O. Adenipekun Department of Botany and Microbiology University of Ibadan Ibadan - NIGERIA e-mail: [email protected]

AFS/ Vol 24/ No 3/ 2002 – pages 94 - 98

© by PSP Volume 24 – No 3. 2002 Advances in Food Sciences

99

ANTIOXIDANT PROPERTIES OF OLIVE PHENOLIC COMPOUNDS ON SUNFLOWER OIL STABILITY

R. S Farag, N. M. Abd-Elmoien and E. A. Mahmoud

Biochemistry Department, Faculty of Agriculture, Cairo University, Giza, Egypt.

SUMMARY The phenolic compounds from ripe leaves and fruits

of Kronakii olive variety were extracted and fractionated into three major fractions, i. e., free, esterified and resid-ual phenolic acids. These fractions were individually mixed with sunflower oil in different concentrations (100, 200 and 400 ppm) to assess their antihydrolytic and anti-oxidant behaviour. Some measurements of rancidity were conducted by estimating e.g., acid, peroxide and thiobar-bituric acid values for sunflower oil alone and mixed with phenolic components during storage at room temperature. The antihydrolytic and antioxidant phenomena of olive phenolic compounds were compared with BHT activity as a common synthetic antioxidant.

Total and free polyphenols obtained from both leaves

and fruits of Kronakii olive cultivar possessed antihydro-lytic and antioxidant activities increasing with concentra-tion. At 400 ppm level they exhibited remarkable effects, superior to those of BHT, in retarding sunflower oil sta-bility.

KEYWORDS: Polyphenols, olive fruits and leaves, sunflower oil, quality assurance tests, rancidity.

INTRODUCTION

Lipid peroxidation causes various damages not only in living organisms but also in foods. To retard undesir-able changes in lipids due to oxidation it is necessary to add antioxidants to food products before use [1, 2]. The most common antioxidants are tocopherols and synthetic phenolic compounds such as butylated hydroxy anisole (BHA) and butylated hydroxy toluene (BHT). The use of BHT or BHA in food has been decreased because of their suspected action as promoters of carcinogenesis, as well as the general consumer rejection of synthetic food addi-tives [3]. In addition, BHA and BHT are characterized by high volatility and instability at elevated temperatures [4].

Therefore, there is a great need for substituting the aforementioned synthetic antioxidants by other natural antioxidants [1, 5, 6].

Among the most important natural antioxidants are

tocopherols and ascorbic acid. Tocopherols are potent in vivo inhibitors of lipid peroxidation but they are less ef-fective than BHA or BHT as food antioxidants [6]. Melted beeswax and its unsaponifiable constituents were mixed with butter oil or refined cottonseed oil to study the hydrolytic and oxidative effects of the mixtures [7]. The unsaponifiables at different levels exhibited anti-hydrolytic and antioxidant effects on butter oil and refined cottonseed oil, respectively. Xinchu et al. [8] found that petroleum ether, acetic acid, ether and alcohol (95%) extracts of different parts of Salvia plebeia induced an antioxidant activity. Thyme and cumin essential oils were used to prevent cottonseed oil and butter rancidity during storage at room temperature [1]. In addition, thyme and clove essential oils are quite safe and can be applied prac-tically as natural antioxidants for lipids [9]. Charai et al. [10] studied the effect of essential oils obtained from certain aromatic plants as natural antioxidants for olive oil. Their results showed a wide variation in the antioxi-dant activity of the essential oils and the highest activity was observed with Thymus broussonetti essential oil.

The aim of the present work was to extract and frac-

tionate the total polyphenols from the leaves and fruits of Kronakii olive cultivar, i.e., free, esterified and residual phenolic compounds. These fractions were individually added to sunflower oil to increase its stability and to com-pare their antioxidant activity with BHT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Source of olive leaves and fruits

The leaves and ripe olive fruits of Kronakii cultivar were collected during the season 2000 from the Horticul-ture Research Institute, Ministry of Agriculture, Giza, Cairo, Egypt.

© by PSP Volume 24 – No 3. 2002 Advances in Food Sciences

100

Solvents and Reagents

All solvents were distilled before use. Butylated hy-droxy toluene (BHT) and thiobarbituric acid (TBA) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO, USA; and Gerbsaure Chemical Co. Ltd., Germany, re-spectively.

Sunflower oil

Refined sunflower oil was obtained from Cairo Oil and Soap Co., El-Ayat, Giza, Egypt. The oil peroxide and acid values were 2.0 meq/kg and 0.4 mg KOH/1g oil, respectively.

Extraction of olive polyphenols:

The polyphenols of olive fruits and leaves were ex-tracted with ethanol followed by centrifugation at 1,500 g for 15 min. The ethanolic extracts were dried over anhy-drous sodium sulfate and evaporated to dryness [11].

Fractionation of polyphenols

Free, esterified and residual phenolic fractions were separated from olive fruits and leaves of Kronakii cultivar according to the method of Dabrowski and Sosulski [12]. Free phenolic acids were initially extracted with tetrahy-drofuran containing NaBH4 (0.5%), followed by extrac-tion of soluble phenolic esters with a mixture of metha-nol: acetone: water (7:7:6, v/v/v). Alkaline hydrolysis was employed, followed by extraction with a mixture of di-ethyl ether: ethyl acetate: tetrahydrofuran (1:1:1, v/v/v) to obtain the insoluble bound phenolic acids.

Oxidation systems

Different concentrations of total, free, esterified and residual phenolic compounds (100, 200, 400 ppm) and BHT (200 ppm) were individually added to sunflower oil. The antihydrolytic and antioxidant activities of each phe-nolic fraction were examined by the acid, peroxide and thiobarbituric acid tests daily over a period of 18 days. These values were used to compare the effectiveness of the phenolic fractions on sunflower oil stability.

Quality assurance methods

The acid and peroxide values were determined using Standard American Oil Chemists Society methods (A. O. C. S. [13]). The secondary oxidation products were de-termined by the thiobarbituric acid (TBA) test [14]. Three replications were run for each parameter during sunflower oil storage and the mean values are presented in the text.

Statistical analysis

The data of quality assurance tests were subjected to analysis of variance with a randomised complete block design to partition the effects of different parameters [15]. The simple regression coefficient (reaction slope) for acid value was statistically calculated.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

There is currently a great worldwide interest in find-ing new and safe antioxidants from natural sources to prevent food rancidity. The present study was focused on olive polyphenols which do not induce undesirable odour or taste, when separated from olive leaves and fruits of Kronakii variety (very cheap natural source) into 3 major fractions, i.e., free, esterified and residual phenolic com-pounds. These fractions were added individually to sun-flower oil at various concentrations besides the total poly-phenols in order to extend its shelf-life.

The antioxidant and antihydrolytic activities of the various olive phenolic components under study were determined by comparing their efficiency with the most commonly used synthetic antioxidants (BHT, BHA and PG added to fats and oils at concentrations of 100-400 ppm to suppress the development of peroxides during food stor-age (Allen and Hamilton, [16]). For this, in the experi-ment BHT (200 ppm) was mixed only with sunflower oil. The phenolic fractions were added at concentrations of 100, 200 and 400 ppm. The changes in efficiency were determined by the commonly used methods such as acid, peroxide and thiobarbituric acid values.

Fig. 1 shows the changes in acid values of sunflower oil mixed with phenolic fractions of olive leaves and fruits of Kronakii variety, and BHT during storage at room temperature. The acid values for sunflower oil alone, sunflower oil mixed with BHT, and total, free, esterified or residual phenolic fractions linearly increased with the storage period. To evaluate the effectiveness of the phenolic material added to sunflower oil, the reaction slope of the acid value curves was used as a guide in this context. Accordingly, the slope values for the acidity of sunflower oil alone and mixed with BHT (200 ppm), and total (100, 200, 400 ppm) and free (100, 200, 400 ppm) phenolic fractions of Kronakii leaves were 0.5; 0.3; 0.4, 0.3, 0.1; and 0.4, 0.3, 0.2, respectively. The slope values of the acid value curves representing the esterified (100, 200, 400 ppm) and residual (100, 200, 400 ppm) phenolic fractions of Kronakii leaves were identical (0.5). Slope values higher than 0.5 indicate pro-hydrolytic effects, whereas those lower than 0.5 demonstrate anti-hydrolytic activity. Hence, the systems containing BHT, total and free phenolic fractions exhibited an anti-hydrolytic activ-ity. Conversely, esterified and residual phenolic fractions at various levels caused non-significant anti-hydrolytic activity on sunflower oil.

The slope values of sunflower oil acidity using the phenolic fractions of Kronakii fruits were nearly similar to that obtained from the leaves. In general, total and free polyphenols possessed an anti-hydrolytic activity, which was increased by increasing their concentration. Also, one has to point out that the use of the latter two fractions at 400 ppm level significantly exhibited anti-hydrolytic activity and were superior to that of BHT in retarding sunflower oil hydrolytic rancidity.

© by PSP Volume 24 – No 3. 2002 Advances in Food Sciences

101

FIGURE 1 - Effect of total (T), free (F), residual (R) and esterified (E) polyphenolic compounds of Kronakii olive fruits and leaves on the acid value of sunflower oil.

© by PSP Volume 24 – No 3. 2002 Advances in Food Sciences

102

FIGURE 2 -Effect of total (T), free (F), residual (R) and esterified (E) polyphenolic compounds of Kronakii olive fruits and leaves on peroxide value of sunflower oil.

© by PSP Volume 24 – No 3. 2002 Advances in Food Sciences

103

FIGURE 3 – Effect of total (T), free (F), residual (R) and esterified (E) polyphenolic compounds of Kronakii olive fruits and leaves on thiobarbituric acid (TBA) value of sunflower oil.

© by PSP Volume 24 – No 3. 2002 Advances in Food Sciences

104

Fig. 2 shows the changes in peroxide values of sun-flower oil mixed with phenolic fractions obtained for both leaves and fruits of Kronakii olive cultivars during storage. An autocatalytic chain reaction was induced, i.e., the rate of hydroperoxide formation increased non-linearly with the time. Since the curves in Fig. 2 show an increase in perox-ide values with time, the peroxide values at the 14th day of storage for all systems were divided by that of the control (sunflower oil without any additives) to demonstrate the effect on the stability of sunflower oil. Therefore, a value higher than 1.0 indicates pro-oxidant effects while the values lower demonstrate anti-oxidant activity. Sunflower oil mixed only with BHT (200 ppm) was used as a control guide to indicate the anti-oxidant or pro-oxidant activities. The relative peroxide values for BHT (200 ppm), total (100, 200, 400 ppm) and free (100, 200, 400 ppm) phenolic componds of Kronakii leaves were 0.26; 0.40, 0.26, 0.12 and 0.40, 0.26, 0.12, respectively, and those for esterified (100, 200, 400 ppm) and residual (100, 200, 400 ppm) phenolic compounds of Kronakii leaves were all identical (1.0). The relative values for all systems using phenolic compounds from olive fruits were calculated as mentioned before and the values were nearly similar to those obtained from leaves of Kronakii olive cultivar.

The antioxidant values for the systems containing

200 ppm of total and free phenolic compounds from Kronakii olive leaves and fruits exhibited antioxidant activity similar to a system comprised of sunflower oil and BHT (200 ppm). On the other hand, the addition of esterified and residual phenolic compounds to sunflower oil of both leaves and fruits at various concentrations (100, 200, 400 ppm) did not exhibit any antioxidant activ-ity on sunflower oil. It is worth-mentioning that 400 ppm level of total and free phenolic compounds obtained from both leaves and fruits produced superior antioxidant power compared to that of BHT.

Fig. 3 shows the TBA values for the systems sun-

flower oil (control), sunflower oil plus BHT (200 ppm), total (100, 200, 400 ppm), free (100, 200, 400 ppm), esteri-fied (100, 200, 400 ppm) and residual (100, 200, 400 ppm) phenolic compounds extracted from leaves and fruits of Kronakii olive cultivar. The levels of secondary oxidation products from sunflower oil were very low and gradually increased with time. The addition of BHT and total or free phenolic fractions of olive leaves and fruits to sunflower oil significantly decreased the formation of secondary oxidation products at all concentrations, with their de-creasing tendency by increasing the levels of free and total phenolic fractions. The content of secondary oxida-tion products at the 16th day of storage period for sun-flower oil containing 100, 200, and 400 ppm of total and free phenolic compounds extracted from Kronakii leaves were 0.36, 0.21, 0.07 and 0.37, 0.23, 0.07, respectively, and nearly identical to those using the fruit phenolic com-pounds (0.36, 0.21, 0.09 and 0.36, 0.21, 0.07). On the other hand, the esterified and residual fractions of both

fruits and leaves did not cause any significant decrease of the level of secondary oxidation products.

Several authors extracted various phenolic com-

pounds from different plant sources and they generally caused an increase in the shelf-life of some vegetable oils. For instance, polyphenols were extracted from the olive oil using hexane, acetone and ethanol in a simple sequen-tial procedure yielding three fractions, A, B, and C, by Fayad et al. [17]. Fractions B and C were found to contain the highest ortho-diphenol concentrations (about 3%). The addition of purified fraction B at a level of 100 ppm to refined olive or soybean oils partially inhibited the oxidative deterioration when the oils were stored in the dark at 100 ºC. Also, Xing and White [18] reported that the antioxidant activities of oat groats and hulls increased with increasing concentrations. During 20 days of storage the groat extract (0.3%) was not significantly different from tertiary butyl hydroquinone (TBHQ) after day 16, and hull extracts (0.2 and 0.3%) were not significantly different from TBHQ on day 20. The antioxidative activ-ity of the total and free polyphenolic fractions tested, in general, could be attributed to the presence of hydroxyl groups in the phenolic ring. This is supported by the pow-erful antioxiant activites of the well-known synthetic BHT and the natural antioxidant thymol [19, 20]. The antioxidant activity to BHT or thymol is related to the inhibition of hydroperoxide formation. The first step in lipid oxidation is the abstraction of a hydrogen atom from a fatty acid and oxygen involvement gives a peroxy radi-cal. Generally, the antioxidants suppress the abstraction of hydrogen atoms from a fatty acid moiety which leads to the decrease of hydroperoxide formation. It is well-known that the phenolic compounds act as hydrogen donors in this reaction mixture and, therefore, the formation of hydroperoxides is decreased. The results of the present study are in agreement with these statements. The pheno-lic OH groups have to be in the free form and, if attached to other groups (such as glycosidic residues), it would prevent their antioxidant power due to the lack of hydro-gen atoms donated to fatty acid radicals. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that the total and free phenolic com-pounds induced powerful antioxidant effect, while the esterified and residual phenolic compounds exhibited only a low effect on retarding sunflower oil oxidative rancidity.

REFERENCES

[1] Farag, R. S.; Ali, M. N. and Taha, S. H. (1990). Use of some essential oils as natural preservatives for butter. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 68: 188-191.

[2] Buck, D. F. and Edwards, M. K. (1997). Antioxidants to pro-long shelf-life. Food Technology International, 29:33-37.

[3] Namiki; M. (1990). Antioxidants/ antimutagenes in food. Crit. Riv. Food Sci. Nutr., 29: 273-279.

© by PSP Volume 24 – No 3. 2002 Advances in Food Sciences

105

[4] Dapkevicius A.; Venskutonis, R. ; Beek, T. A. and Linssen, J. P. H. (1998). Antioxidant activity of extracts obtained by different isolation procedures from some aromatic herbs grown in Lithuania. J. Sci. Food. Agric., 77 :140-146.

[5] Pratt, D. E. (1992) . Natural antioxidants from plant materi-als, in phenolic compounds in food and their effect on health. Ed. By M. T. Hung, C.T. Ho and C. Y. Lee, American Chemical Society, New York, PP. 55-71.

[6] Tsimidou, M. and Boskou, D. (1994). Antioxidant activity of essential oils from the plants of the lamiacae family. G. Charalambous (Ed) Spices Herbs and Edible fungi.

[7] Farag, R. S.; Hassan, M. N. A. and Ali, F. M. (1993). Bees-wax and its unsaponifiable components as natural preserva-tives for butter and cottonseed oils. J. Food Sci. & Nutr., 44: 197-205.

[8] Xinchu, W., Goufeng, C. ; Xinwei, D. and Shan, D. (1998). Antioxidant activity of lizhicaa (Salvia plebeia R. Br.). J. Chinese Cereals and Oils Association. 13: 25-28.

[9] Farag, R. S.; Abu-Raiia, S. H. and El-Desoy, G. E. and El-Baroty, G. S. A. (1991). Safety evaluation of thyme and clove essential oils as natural antioxidants. African J. of Ag-ricultural Sciences, 18:168-176.

[10] Charai, M.; Faid, M. and Chaouch, A. (1999). Essential oils from aromatic plants (Thysmus broussonetti Boiss., Ori-ganum compactum Benth., and citrus limon (L.) N. L. Burm.) as natural antioxidants for olive oil. J. Essen. Oil Res., 11 : 517-521.

[11] Kanner, J.; Edwin, F., Rina, G.; Bruce, G. and John, E. (1994). Natural antioxidants in graps and wines. J. Agric. Food. Chem., 42, 64-69.

[12] Dabrowski, K. J. and Sosulski, F. W. (1984). Composition of free and hydrolyzable phenolic acids in defatted flours of ten oilseeds. J. Agric Food Chem. 32: 128-130.

[13] A.O.C.S. (1985). Official and Tentative Methods of the American Oil Chemists Society, 3rd ed. American Oil Chem-ists Society, Champaign, IL.

[14] Ottolenghi, A. (1959). Interaction of ascorbic acid and mitochondrial lipids. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 79:355-363.

[15] Steel, R. G. D., Torrie, J.H. (1980). Principles and procedures of Statistics, 3rd edn. McGraw-Hill, New York, U.S.A.

[16] Allen, J. C. and Hamilton. R. J. (1983). Rancidity in Food., pp. 85-173. London and New York. Applied Science Pub-lishers.

[17] Fayad, Z.; Sheabar, A. and Neemann, I. (1989). Separation and concentration of natural antioxidants from the rape of ol-ives., 65:990-993.

[18] Xing, Y. and White, P. (1997). Identification and function of antioxidants from oat groats and hulls. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 74 :303-307.

[19] Farag, R. S. and El-Khowas, K. H. M. M. (1989). Influence of γ-irradiation and microwaves on the antioxidant property of some essential oils. Ibid, 49:109-115

[20] Topallar. H., Bayrak, Y. and Iscan, M. J. (1997). A kinetic study of the autooxidantion of sunflower seed oil. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 74: 1323-1327.

Received for publication: May 21, 2002 Accepted for publication: July 17, 2002 CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

R. S. Farag Biochemistry Department Faculty of Agriculture Cairo University P.O.Box 12613 Giza - EGYPT e-mail: [email protected]

AFS/ Vol 24/ No 3/ 2002 – pages 99 - 105

© by PSP Volume 24 – No 3. 2002 Advances in Food Sciences

106

GLYKOSIDISCH GEBUNDENE AROMASTOFFE IN HOPFEN (Humulus lupulus L.):

1. ENZYMATISCHE FREISETZUNG VON AGLYCONEN

H. Kollmannsberger und S. Nitz

Department Lebensmittel und Ernährung, Lehrstuhl für Chem.-Techn. Analyse u. Chem. Lebensmitteltechnologie; Technische Universität München,

Wissenschaftszentrum Weihenstephan für Ernährung, Landnutzung und Umwelt, Weihenstephaner Steig 23, D-85350 Freising-Weihenstephan, FRG

GLYCOSIDICALLY BOUND FLAVOUR COMPOUNDS IN HOP (Humulus lupulus L.): 1. ENZYMATICAL LIBARATION OF AGLYCONES.

SUMMARY

The efficiency of different enzyme preparations (al-mond ß-glucosidase, glucosidase from Aspergillus niger, pectinase, hesperidinase, α-amylase, a amylase-mixture, a hemicellulase preparation) for the cleavage of glycosidically bound flavour compounds of hops (Humulus lupulus L.) was investigated. Enzymes were added to either synthetic ß-D-glucosides (phenyl- and octyl-) or hop extracts. The hop extracts were made by extraction with a water-methanol mixture, or by hot-water extraction and subse-quent adsorption on an Amberlite XAD-2 resin. The iso-lated aglycones were investigated by gas chromatography - mass spectrometry. Main compounds among the agly-cones were 3-methylbutan-2-ol, 3- and 2-methyl-butan-1-ol, 3-methyl-2-buten-1-ol, 3-methylpentan-2-ol, 3(Z)-hexenol, hexanol, 1-octen-3-ol, benzylalcohol, 2-phenyl-ethanol, linalool, α-terpineol, methylsalicylate, 2,6-di-methylocta-2,7-dien-1,6-diol, 3-hydroxy-7,8-dihydro-ß-ionol, 3-hydroxy-5,6-epoxy-ß-ionol, vomifoliol and 7,8-dihydro-vomifoliol. Additionally small amounts of 3-hy-droxy-ß-damascone, a precursor of the sensorial impor-tant ß-damascenone could be found among the aglycones. Best yields of aglycones could be achieved with glucosi-dase from Aspergillus niger and with rapidase (a hemicel-lulase preparation with glycosidic activities). Commer-cially available α−amylase was found to be not suitable for hydrolysis of hop glycosides.

KEYWORDS: Humulus lupulus L., hop flavour, glycosidically bound volatiles, glycosides, aglycones, enzymatic hydrolysis.

ZUSAMMENFASSUNG

Verschiedene Enzympräparate (ß-Glucosidase aus Mandeln, Glucosidase aus Aspergillus niger, Pectinase, Hesperidinase, α-Amylase, ein Amylase-Gemisch, ein Hemicellulase-Präparat) wurden auf ihre Eignung zur Spaltung von glycosidisch gebundenen Aromastoffen des Hopfens (Humulus lupulus L.) untersucht. Dazu wurden synthetische ß-D-Glucoside (Phenyl- und Octyl-), wäss-rig-methanolische Hopfenextrakte und säulenchroma-tographisch über Amberlite XAD-2 aufgereinigte Hop-fenextrakte mit den Enzymen versetzt und die extraktiv abgetrennten Aglycone gaschromatographisch-massen-spektrometrisch untersucht. Als mengenmäßig dominante Aglycone fanden sich 3-Methylbutan-2-ol, 3- und 2-Me-thylbutan-1-ol, 3-Methyl-2-buten-1-ol, 3-Methylpentan-2-ol, 3(Z)-Hexenol, Hexanol, 1-Octen-3-ol, Benzylalkohol, 2-Phenylethanol, Linalool, α-Terpineol, Methylsalicylat, (E)-2,6-Dimethyl-Octa-2,7-dien-1,6-diol, 3-Hydroxy-7,8-dihydro-ß-Ionol, 3-Hydroxy-5,6-epoxy-ß-Ionol, Vomifo-liol und 7,8-Dihydro-Vomifoliol. 3-Hydroxy-ß-Damas-con, aus dem durch Dehydratisierung der starke Geruchs-stoff ß-Damascenon gebildet werden kann, war ebenfalls in geringen Mengen unter den Aglyconen nachweisbar. Die besten Ausbeuten an Aglyconen ergaben sich mit Glucoside aus Aspergillus niger und mit Rapidase (ein Hemicellulase-Präparat mit glycosidischen Nebenaktivitä-ten). Handelsübliche α−Amylase eignet sich nicht zur Spaltung von Hopfenglycosiden.

EINLEITUNG

Glycoside (früher �Heteroside� genannt) sind eine umfangreiche Gruppe von Pflanzeninhaltsstoffen, welche sich aus einem oder mehreren Zuckern und einem oder mehreren Aglyconen (= Nicht-Zucker-Molekül-Anteilen) zusammensetzen. Das Aglycon ist dabei über ein Sauer-stoffatom (Ether-Bindung) an ein Halbacetal-Kohlenstoff-atom eines Zuckers gebunden. Der am häufigsten natür-

© by PSP Volume 24 – No 3. 2002 Advances in Food Sciences

107

lich vorkommende Zuckerrest der Glycoside ist die in ß-Stellung verknüpfte D-Glucose. Man nennt diese Glyco-side dann ß-D-Glucoside. Auch Disaccharid-Glycoside (z.B. Glucosyl-, Arabinosyl-, Rhamnosyl-, Xylosyl- und Apiosyl-Gucoside) kommen in der Natur vor [1].

Schon früh wurde die Bedeutung von Glycosiden als

Vorstufen für wertgebende Aromastoffe in Vanille [2], Rosenblättern [3] und Weintrauben [4] erkannt. Seither konnte eine Vielzahl von Glycosiden mit über 200 unter-schiedlichen Aglycon-Strukturen in fast 170 Pflanzenar-ten aus etwa 50 Pflanzenfamilien nachgewiesen werden [1, 5]. Auch in den Rückständen der CO2-Hochdruck-extraktion von Hopfen (Humulus lupulus L.) wurde kürz-lich das Vorkommen glycosidisch gebundener Aroma-stoffe beschrieben [6,7].

Glycoside werden als Speicher- bzw. Transportform

von Aromastoffen angesehen [1]. Möglicherweise kommt ihnen auch eine gewisse Schutzwirkung zu. Empfindliche Zellmembranen könnten von hohen Gehalten an freien phenolischen oder terpenoiden Alkoholen geschädigt werden [5]. Glycoside sind geruchlos, entsprechende Aro-mastoffe lassen sich daraus jedoch durch Erhitzen im Sau-ren oder durch enzymatische Hydrolyse freisetzen. Emp-findliche Aglyconstrukturen können bei der Hydrolyse der Glycoside strukturell verändert werden [8 - 10]. Beispiele dafür sind die Bildung des äußerst geruchsaktiven ß-Damascenons aus 3-Hydroxy-ß-Damascon und 3-Hydroxy-7,8-Dehydro-ß-Jonol [11], die Bildung der Rosenoxide aus 2,6-Dimethyl-3-Octen-2,8-diol [12] oder die Bildung von Linalool und α-Terpineol aus Neryl-glycosid [9].

Glycosidextrakte können nach entsprechender Deri-

vatisierung auch direkt gaschromatographisch untersucht werden [1]. Meist begnügt man sich jedoch damit, nur die durch gezielte enzymatische Hydrolyse freisetzbaren Aglykone zu messen. Hierzu müssen die Glycoside zu-nächst aus dem Pflanzenmaterial isoliert werden. Bei Blattmaterial wird üblicherweise mit kochendem Wasser [13,14], Methanol [15] oder einem Wasser-Methanol-Gemisch (80:20 v/v) [6] extrahiert. Methanolzusatz be-wirkt dabei auch eine Fällung von Protein (und damit eine Inaktivierung von Enzymen) [13]. Andere störende Be-standteile wie Polyphenole können durch Bindung an Polyvinylpyrrolidon eliminiert werden [13]. Dann folgt meist eine säulenchromatographische Aufreinigung an RP-18 [3,16,17] oder Amberlite XAD-2 [11,13,18,19]). Um freie Zucker auszuwaschen wird zunächst mit Wasser eluiert. Dem folgt meist eine Elution freier Aromastoffe mit Pentan [11,18,19], Pentan-Ether [13], Ether [6] oder Pentan-Dichlormethan [20,21], bevor die Glycoside mit Methanol [13,19,21,22] oder Ethylacetat [18,20] abgelöst werden. Die so gewonnene Glycosidfraktion kann nun (nach Entfernen des Methanols) unter definierten Bedin-gungen (optimaler pH-Wert und Temperatur) einer enzy-matischen Hydrolyse unterworfen werden. Nach entspre-chender Inkubationszeit (8h [14,15], 12h [18], 16h [8,19],

24h [6,23,24] 48 h [17], 72h [22,25]) werden die Aglycone isoliert und gaschromatographisch-massenspektrometrisch nachgewiesen. Einige Schnellmethoden verzichten auf die säulenchromatographische Aufreinigung [14], wobei hier eine Glycosidhydrolyse nur mit einer, gegenüber störenden Bestandteilen toleranten Glucosidase gelingt [26].

Zur enzymatischen Spaltung der Glycoside verwen-

det man meist ß-Glucosidase aus Mandeln (�Emulsin�, EC 3.2.1.21) [22]. Pectinasen (Pectinol [14], Rohapect C [20] Pectinase aus A.niger [19]) können bessere Ergebnis-se liefern. Pectinol VR ist weniger geeignet [27]. Die Effizienz der Hydrolyse hängt nicht nur von der Inkubati-onsdauer und dem pH-Wert, sondern auch von der Struk-tur der Aglycone und dem Ursprung des Enzymes ab [1, 28, 29]. Tertiäre Alkohole wie Linalool und α-Terpineol werden besser durch Glucosidase aus Aspergilus niger als durch Glucosidase aus Mandeln gespalten [28]. Die Unspezifität gegenüber tertiären Alkoholen ist vielen pflanzlichen Glycosidasen eigen [26]. Zur Spaltung von Glycosiden des Vomifoliols und anderer nor-Carotinoide eignet sich kommerziell erhältliche Hesperidinase [23]. Zur Analyse von Aglyconen hat sich auch ein Hemicellu-lase-Präparat der Fa. Gist-Brocades (Seclin, Frankreich) bewährt [21].

Mittels einer Appatatur zur kontinuierlichen Freiset-

zung von Aglyconen durch mehrmalige enzymatische Spaltungen der selben Probe (Simultane Enzym Katalyse Extraktion, SECE) [23] konnte beobachtet werden, daß sich die Konzentration der freigesetzten Aglycone mit der Zeit ändert. Die sensorisch interessanten C13-nor-Isoprenoide wurden dabei erst in späteren Hydrolysestu-fen in größeren Mengen freigesetzt [23].

Problematisch ist auch die Hydrolyse von Disaccha-

rid-Glycosiden, da hier zuerst der an die Glucose gebun-dene andere Zuckerrest abgespalten werden muß, um dann der ß-Glucosidase als Substrat dienen zu können [30]. Entsprechende Enzymnebenaktivitäten sind hierbei für eine möglichst vollständige Glycosidspaltung unerläß-lich. Dies läßt sich auch durch die kombinierte Verwen-dung mehrerer Enzympräparate erreichen [21].

Im Rahmen unserer Untersuchungen über glycosi-

disch gebundene Aromastoffe des Hopfens berichten wir hiermit über die Eignung verschiedener Enzympräparate zur Freisetzung von Aglyconen aus Hopfenglycosiden.

MATERIAL UND METHODEN

Probenmaterial: getrocknete Hopfendolden (gerntet im Jahr 2000) der Sorten Hallertauer Mittelfrüh (HHA), Hallertauer Tradition (HHT), Hallertauer Magnum (HHM), Hallertauer Hersbrucker (HHE), Czechischer Saazer (CSA) bezogen über Fa. Hopsteiner (HHV), D-84048 Mainburg. Phenyl-ß-D-Glucosid und Octyl-ß-D-

© by PSP Volume 24 – No 3. 2002 Advances in Food Sciences

108

Glucosid von Sigma-Aldrich, Chromatographie-Harz Amberlite XAD-2 von Sigma-Aldrich, Methanol puriss p.a. (99,8% GC) von Fluka, Polyclar AT pract von Serva.

Enzyme: ß-D-Glucosidase aus Mandeln (Emulsin, EC

3.2.1.21; 6,3 U/mg), Glucosidase aus Aspergillus niger (76 U/g), Pectinase aus Aspergillus niger (EC 3.2.1.15; 2,5 U/mg), Hesperidinase (7 U/g mit α-L-Rhamnosidase und ß-D-Glucosidase Activität) von Sigma-Aldrich. α-Amylase (Termamyl-120L) und Amylase-Mix (SAN Super 240L mit α-Amylase, Gluco-Amylase, Protease, stabilisiert mit Benzoe- und Sorbinsäure) von Novozymes DK-2880 Bagsvaerd. Ein nicht komerziell verfügbares Hemicellulase-Präparat mit glycosidischen Nebenaktivitä-ten (�Rapidase F-64�) wurde uns dankenswerterweise von Herrn Dipl.-Ing. B. Heimann, DSM Food Specialities, D-44319 Dortmund zur Verfügung gestellt (Dieses Präparat entspricht der in der Literatur [21] beschriebenen Hemi-cellulase REG2, von Gist-Brocades, Frankreich).

Modell-Lösung: jeweils 2,44 µM Phenyl-ß-D-Glucosid

und 1,62 µM Octyl-ß-D-Glucosid in 25 ml Phosphat-Citrat-Puffer (21 g Citronensäure-monohydrat und 71,5 g Na2HPO4 x 12 H2O pro Liter H2O dest., pH 5,0) lösen.

Hopfen-Extraktion: ca. 80 g Hopfendolden (Gemisch

aus HHA, HHE und CSA) im Mörser fein zerreiben und nach Zusatz von 19,5 µM Phenyl-ß-D-Glucosid mit einer Mischung aus 800 ml Methanol und 200 ml H2O 16 h rühren. Flüssige Phase über Glaswolle abdekantieren, 10 min mit 40 g Polyclar rühren und filtrieren. Am Rotati-onsverdampfer Methanol abziehen (40°C, 250-70 mbar). Wässrige Lösung (ca. 150 ml) 3mal mit 100 ml Diethy-lether ausschütteln. Anschließend zur Trockne einengen und Rückstand in 200 ml Phosphat-Citrat-Puffer, pH 5,0 aufnehmen und auf 8 Inkubationsgefäße verteilen. Jeder Ansatz enthält demnach 2,44µM Phenyl-ß-D-Glucosid und ca. 10 g Hopfen in 25 ml Puffer.

TABELLE 1 - Enzymzusatz bei den Inkubationsversuchen.

Probe Enzym Menge BW keines keine AMY α-Amylase 2,5 ml AMX Amylase-Mix 2,5 ml PCT Pectinase 100 mg HSP Hesperidinase 250 mg GLM Mandel-Glucosidase 25 mg GLA Asp. niger-Glucosidase 50 mg HEM Hemicellulase 25 mg

Vergleich der Enzymaktivitäten: Die Modell-Lösungen

bzw. die Hopfenansätze jeweils mit Enzympräparat verset-zen (siehe Tab. 1) und 66 h im Wasserbad (40°C) unter Rühren inkubieren. Anschließend Zugabe von 0,5 ml Stan-

dard-Lösung (Methyl-Octanoat 1g/l) und Isolierung der freigesetzten Aglycone durch 4-maliges Ausschütteln mit 50 ml Diethylether. Trocknung der Extrakte über Na2SO4 und Aufkonzentrierung an einer Vigreuxkolonne (40°C).

Säulenchromatographische Reinigung an XAD-2: jeweils

25 g fein zerriebene Hopfendolden (HHA, HHT, HHE, HHM, CSA) mit 5 µM Phenyl-ß-D-Glucosid versetzen und mit kochendem Wasser extrahieren. Nach Klärung mit Polyclar und Proteinfällung mit Methanol, zur Trockne einengen und in Wasser gelöst auf eine XAD-Säule auf-bringen. Elution mit 1 Liter H2O (6 ml/min), 500 ml Pen-tan-Dichlormethan (2:1 v/v, 7 ml/min) und 500 ml Methanol (5ml/min). Methanolisches Eluat zur Trockne einengen und in 50 ml Phosphat-Citrat-Puffer pH 5,0 aufnehmen. Jeweils 25 ml ohne Zusatz und 25 ml mit 25 mg ß-Glucosidase, 24 h bei 40°C unter Rühren inkubieren (vgl. [31]). Extraktion mit Diethylether wie oben.

Gaschromatographie-Massenspektrometrie (GC-MS): HP 5890 Ser. II Gaschromatograph direkt gekoppelt

mit Finnigan 8200 Magnetsektorfeld-Massenspektro-meter. EI-Modus, 70 eV, 33-400 amu, Injektor 250 °C, Transferleitung 230 °C, Ionenquelle 240 °C Temperatur-programm 60°C (5min), mit 2°C/min auf 260°C. Träger-gas Helium (1,15 ml/min bei 60°C), Split 1:10. Trennsäule TS1: SE 54 (DB 5 J&W), 30m x 0,25mm i.D., df 0,25 µm.

Siemens SiChromat II GC direkt gekoppelt mit Finnigan

8222 Magnetsektorfeld-MS EI-Modus, 70 eV; 35-600 amu, Injektor 250 °C; Transferleitung 200 °C Ionenquelle 180 °C; Sniffing-Modul 250 °C; Temperaturprogramm 100°C, mit 5min auf 250°C bzw. 60°C mit 5°C/min auf 250°C. Trä-gergas Helium (3 ml/min bei 100 °C); Split 1:10; Trennsäule TS2: SE54 (Supelco SPB-5); 30 m x 0,53 mm i.D., df 1,5 µm. Der Trägergasstrom wird am Ende der Kapillartrennsäule über ein Live-T-Stück aufgesplittet zum MS und zur mit angefeuchteter Preßluft gespülten Sniffing-Maske. (Splitverhältnis ca. 1:1)

Finnigan 9600 GC direkt gekoppelt mit Finnigan

4500 Quadrupole-MS. EI-Modus, 70 eV, 33-400 amu, Injektor 200°C, Transferleitung 200 °C, Ionenquelle 150°C, Temperaturprogramm 60°C (10min) mit 2°C/min auf 200°C. Trägergas Helium 1 ml/min, Split 1:10, Trennsäule TS3: CW20M (Permabond, M&N) 50 m x 0,25 mm i.D., df 0,25 µm.

Identifizierung: Die Identifizierung erfolgte durch

Vergleich von Massenspektren (MS) und Retentionsindi-ces (RITS1, RITS2 und RITS3) mit Daten von authenti-schen Referenzsubstanzen bzw. entsprechend abgesicher-ten Daten einer unter denselben GC-MS-Bedingungen erstellten MS/RI-Bibliothek (Kollmannsberger, Weihen-stephan). Wo keine Vergleichssubstanz zur Verfügung stand, wurde zur Identifizierung auf entsprechende Litera-turangaben zurückgegriffen.

© by PSP Volume 24 – No 3. 2002 Advances in Food Sciences

109

ERGEBNISSE UND DISKUSSION

In Tabelle 2 sind die, mit den verschiedenen Enzym-präparaten aus synthetischen Glucosiden freisetzbaren Gehalte der Aglyconen wiedergegeben. Es fällt auf, daß bei 66-stündiger Inkubation bereits im Blindwert ein Um-satz von 10 % (Octyl-Glucosid) bzw. 24 % (Phenyl-Glucosid) stattfindet. Bei 24-stündiger Inkubation liegen diese Werte noch deutlich niedriger (3-7% der theoreti-schen Menge).

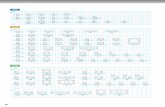

TABELLE 2 - Freisetzung von Aglyconen (µg/Ansatz) aus synthetischem ß-D-Phenyl- (PHE) und ß-D-Octyl-Glucosid (OCT) durch verschiedene Enzympräparate (Inkubation 66 h, 40°C)

Probe: PHE a) (+/-)b) OCT a) (+/-)b) theoret. c) 229 210 BW 54 3 22 2 AMY 134 3 62 4 AMX 251 18 196 15 PCT 191 4 174 5 HSP 200 2 166 2 GLM 201 9 200 7 GLA 231 10 216 19 HEM 233 11 180 7

a) Mittelwert aus Doppelbestimmung

b) Abweichung bei Doppelbestimmung c) theroretisch erzielbarer Wert

24

59

110

83 87 88101 102

020406080

100120

BW AMY AMX PCT HSP GLM GLA HEM

1030

9383 79

95 10386

020406080

100120

BW AMY AMX PCT HSP GLM GLA HEM

ABBILDUNG 1 - Hydrolyse (%) von synthetischem ß-D-Phenyl- (PHE) und ß-D-Octyl-Glucosid (OCT) durch verschiedene Enzym-präparate (Inkubation 66 h, 40°C).

Die schlechteste Ausbeute an Aglyconen erhält man

mit dem α-Amylase-Präparat (AMY), während das Amy-lase-Gemisch (AMX) mit den synthetischen Glucosiden

erstaunlich hohe Werte liefert. Die beiden Glucosidasen (GLM, GLA) zeigen in den eingesetzten Konzentrationen eine höhere Spezifität für das aliphatische Octyl-ß-D-Glucosid. Das Hemicellulase-Präparat (HEM) und die Hesperidinase (HSP) scheinen das Phenyl-ß-D-Glucosid als Substrat zu bevorzugen. In Abb.1 sind die prozentua-len Ausbeuten an Aglyconen bezogen auf den theoretisch erreichbaren Wert dargestellt. Bei nur 24-stündiger Inku-bation mit ß-Glucosidase bzw. Hemicellulase betragen die Ausbeuten bei beiden Aglyconen etwa 76-78 % des nach 66-stündiger Inkubation erzielbaren Wertes. Neben der Inkubationsdauer ist natürlich auch die Konzentration an Enzym von entscheidenden Einfluß auf die Effizienz der Hydrolyse. Bei Inkubation von synthetischem Phenyl-ß-D-Glucopyranosid mit nur 25 mg A. niger Glucosidase wur-den nur 73 % des mit 50 mg der Glucosidase unter ansons-ten gleichen Bedingungen freigesetzten Phenols gemessen.

In Tabelle 3 sind die, mit den verschiedenen Enzym-

präparaten aus einer Hopfenprobe freisetzbaren Aglycone zusammengestellt. Die Ausbeuten einiger typischer Agly-cone sind in Abb. 2 graphisch dargestellt. Wiederum bestätigt sich die geringe Aktivität der α-Amylase (AMY), sowie die hohe Spezifität der A. niger Glucosida-se (GLA) und der Hemicellulase (HEM) für das auch hier zugesetzte Phenyl-ß-D-Glucosid. Das Amylase-Gemisch (AMX) zeigt in dem nicht säulenchromatographisch auf-gereinigten Hopfenextrakt eine deutlich geringere Hydro-lyse-Effizienz für das Phenylglucosid als in der Modell-Lösung (Abb. 1). Möglicherweise wirken hier nicht abge-trennte Hopfenbestandteile inhibierend.

Sehr gute Ausbeuten an allen Aglyconen erzielt man

mit der A. niger Glucosidase (GLA), während die anderen Enzympräparate offensichtlich eine starke Substratspezifi-tät aufweisen.

1-Octen-3-ol wird am besten durch die beiden Gluco-

sidasen (GLM, GLA) freigesetzt (Abb. 2). Bei den tertiä-ren Alkoholen α-Terpineol und Linalool lassen sich mit dem Hemicellulase-Präparat (HEM) die besten Ergebnis-se erzielen. Hesperidase (HSP) liefert nur bei einigen nor-Carotinoid-Derivaten brauchbare Resultate. Mit dem Amylase-Gemisch (AMX) werden die höchsten Werte für 3-Methyl-2-Pentanol und Vomifoliol erzielt (Abb. 2). Während mit Mandel-Glucosidase (GLM) nur ver-gleichsweise wenig Vomifoliol gefunden wird, läßt sich damit der höchste Gehalt an 3-Hydroxy-5,6-epoxy-ß-Jonol freisetzen (Tab.3).

2,6-Dimethyl-2,7-Octadien-1,6-diol (= 8-Hydroxy-

Linalool) verhält sich sehr ähnlich wie andere primäre Alkohole (Z.B. 3-Methylbutanol, 3Z-Hexenol und Benzy-lalkohol). Dies könnte ein Hinweis darauf sein, daß es über die endständige und nicht über die tertiäre OH-Gruppe glykosidisch verknüpft ist.

PHE

OCT

© by PSP Volume 24 – No 3. 2002 Advances in Food Sciences

110

ABBILDUNG 2 - Freisetzung von Aglyconen aus Hopfenextrakten durch verschiedene Enzympräparate

Phenol

7 26

170200 192 204

253225

050

100150200250300

BW AMY AMX PCT HSP GLM GLA HEM

Linalool

0 0 3 5 6 715

22

0102030

BW AMY AMX PCT HSP GLM GLA HEM

3-Hydroxy-ß-Damascon

0 01

45

3

65

0123456

BW AMY AMX PCT HSP GLM GLA HEM

3-Hydroxy-7,8-dihydro-ß-Jonol

0 5

45 43 58 59

132

74

0

50

100

150

BW AMY AMX PCT HSP GLM GLA HEM

2,6-Dimethyl-2,7-Octadien-1,6-diol 2

1846

124 134

77

124

237

142

0

50

100

150

200

250

BW AMY AMX PCT HSP GLM GLA HEM

7,8-dihydro-Vomifoliol

0 0

31

119 9

10

02468

1012

BW AMY AMX PCT HSP GLM GLA HEM

1-Octen-3-ol

0 334 21

59 74

124

55

0

50

100

150

BW AMY AMX PCT HSP GLM GLA HEM

Vomifoliol

6

30

60

15

40

12

40

20

0

20

40

60

80

BW AMY AMX PCT HSP GLM GLA HEM

3-Z-Hexenol

0 0

80 87

41

70

140

98

0

50

100

150

BW AMY AMX PCT HSP GLM GLA HEM

Benzylalkohol

1 9

84 9544

117

235

175

050

100150200250

BW AMY AMX PCT HSP GLM GLA HEM

Phenol

© by PSP Volume 24 – No 3. 2002 Advances in Food Sciences

111

TABELLE 3 Freisetzung von Aglyconen aus einem Hopfenextrakt durch verschiedene Enzympräparate (Inkubation 66 h, 40°C)

(Peak-Flächenwerte ausgewählter Massenfragmente - bezogen auf Standard Methyloctanoat)

BW AMY AMX PCT HSP GLM GLA HEM Phenol (Standard) 7 26 170 200 192 204 253 225 3-Methylbutan-1-ol 1 5 18 16 8 18 35 27 3-Methyl-2-Buten-1-ol 0 56 34 51 44 65 57 75 3-Methylpentan-2-ol 0 17 171 16 38 37 61 58 3-(Z)-Hexen-1-ol 0 0 80 87 41 70 140 98 1-Octen-3-ol 0 3 34 21 59 74 124 55 4,6-Dimethylheptan-2-ol ? 0 0 7 9 5 9 16 12 Benzylalcohol 1 9 84 95 44 117 235 175 2-Phenylethanol 0 0 16 29 10 20 37 35 Methylsalicylat 1 6 24 14 13 30 49 31 Linalool 0 0 3 5 6 7 15 22 α-Terpineol 0 22 25 20 33 36 35 44 (Z)-2,6-Dimethyl-2,7-Octadien-1,6-diol 5 8 15 17 5 14 26 14 (E)-2,6-Dimethyl-2,7-Octadien-1,6-diol 18 46 124 134 77 124 237 142 3-Hydroxy-7,8-dihydro-ß-Jonol 0 5 45 43 58 59 132 74 3-Hydroxy-5,6-epoxy-ß-Jonol 0 0 13 5 10 25 16 12 3-Hydroxy-ß-Damascon 0 0 1 4 5 3 6 5 Vomifoliol 6 30 59 16 40 12 39 21 7,8-dihydro-Vomifoliol 0 0 3 1 11 9 9 10 Tabelle 4 enthält alle in den 5 Hopfensorten nach säu-

lenchromatographischer Vorreinigung und enzymatischer Spaltung identifizierten Aglycone. Die Identifizierung erfolgte durch Vergleich von Massenspektrum (MS) und Retentionszeit (RT) mit einer institutseigenen Referenz-Datei bzw. über Literaturdaten (siehe Tab. 4) Die wich-tigsten Strukturformeln sind in den Abbildungen 3-6 wiedergegeben. In einigen Proben waren auch geringe Mengen an 3Z-Hexenal, Benzaldehyd und Phenylacetal-dehyd nachweisbar. Diese Carbonylverbindungen sind Oxidationsprodukte der korrespondierenden glycosidisch gebundenen Alkohole und wurden nicht eigens aufge-führt. Hydroxy-Benzoesäure, Vanillinsäure, Hydroxy-Zimtsäure und Ferulasäure konnten besonders nach en-zymatischer Spaltung mit dem Hemicellulase-Präparat Rapidase in größeren Mengen nachgewiesen werden.

2-(2-Butenyliden)-3,3-Dimethyl-5-(2-oxopropyl)-Tetra-

hydrofuran ist ein bekanntes Umwandlungsprodukt des 3-Hydroxy-5,6-epoxy-ß-Jonols [33] und stellt daher ein Artefakt dar. ß-Damascenon trat bei Sniffing-GC-MS-Analysen durch seinen typischen Geruch zur entsprechen-den Retentionszeit hervor, die vorhandene Konzentration reichte jedoch in den meisten Proben nicht für einen gesi-cherten massenspektrometrischen Nachweis aus.

Mittels Sniffing-GC-MS konnte, neben einigen noch

nicht identifizierten Substanzen, besonders den in Tab. 5 aufgeführten Bestandteilen der Aglycon-Fraktion ein eindeutiger Geruch zugeordnet werden. Darüberhinaus

wird ein �muffig-ranziger� Geruch bei 3- und 2-Methylbuttersäure wahrgenommen. Da diese Säuren auch im nicht mit Glucosidase versetzten Blindwert auftreten, wurde ihnen keine weitere Beachtung geschenkt.

Unterzieht man einen Glycosidextrakt aus Hopfen ei-

ner sauren Hydrolyse (Kochen unter Rückfluß; 1 h bei pH 2,7) lassen sich massenspektrometrisch unter anderen α-Terpineol, die beiden furanosiden Linalooloxide, Lina-lool, Limonen, p-Menth-1-en-9-al und ß-Damascenon nachweisen. Das äußerst geruchsaktive ß-Damascenon dürfte dabei aus dem glycosidisch gebundenem 3-Hydroxy-ß-Damascon hervorgehen [11].

Der Nachweis von Glycosiden im Hopfen dürfte vor

allem für die Bierbereitung von Interesse sein [6,7]. Da die freien Aromastoffe des Hopfens beim Würzekochen weitgehend verloren gehen, stellen glycosidisch gebunde-ne Aromastoffe eine zusätzliche Quelle zur Ausbildung des Hopfenaromas im Bier dar. In Fortführung dieser Arbeiten konnten wir zeigen, das die Glycoside den Brauprozeß überstehen und sich im gehopften Jungbier dieselben Aglycone freisetzen lassen wie im Hopfen. Besonders Linalool und ß-Damascenon treten bei Snif-fing-GC-MS-Analysen von gehopftem Bier geruchlich in Erscheinung während sie in ungehopftem Bier praktisch ohne Bedeutung sind. Inwiefern diese Geruchsstoffe zum Hopfenaroma des Bieres einen Beitrag leisten, soll Ge-genstand weiterer Untersuchungen sein.

© by PSP Volume 24 – No 3. 2002 Advances in Food Sciences

112

TABELLE 4 - Durch enzymatische Spaltung freisetzbare Aglycone in säulenchroma- tographisch aufgereinigten wässrigen Extrakten aus verschiedenen Hopfensorten

Nr. Verbindung RI-TS1

RI-TS2

RI-TS3 m/e Identifi-

zierung

1 Butan-2-ol 613 1027 45,59-41,43,73 MS,RT 2 2-Methyl-3-Buten-2-ol 622 1041 43,71,59-53,86 MS,RT 3 2-Methyl-Propan-1-ol 632 1097 43-43,41,42,33,74 MS,RT 4 Butan-1-ol 674 1154 56-41,43,42,73 MS,RT 5 3-Methyl-Butan-2-ol 689 1096 45,55,73-43,87 MS,RT 6 3-Methyl-3-Buten-2-ol 696 1179 43,71-41,45,53,58,86 MS,RT 7 Pentan-3-ol ? 1114 59-41-55,58,57 MS,RT 8 Pentan-2-ol ? 1128 45-55,73,43 MS,RT 9 3-Methyl-Butan-1-ol 726 1217 55,42,70,41,43 MS,RT

10 2-Methyl-Butan-1-ol 730 1216 57,56,41,70 MS,RT 11 Pentan-1-ol ? 1263 42,55,70,41 MS,RT 12 4-Methyl-Pentan-2-ol 753 1175 45-43,69,84,87,57 MS,RT 13 3-Methyl-2-Buten-1-ol 793 772 1334 71,53,41,67,68,86 MS,RT 14 3-Methyl-Pentan-2-ol 789 1208 45-56,41,69,84,87 MS,RT 15 3Z-Hexenol 851 854 1393 67,41,82-55,69 MS,RT 16 Hexanol 865 864 1366 56-43,41,69,55,84 MS,RT 17 Cyclohexanol ? 887 898 1411 57,82-67,55,41 MS 18 1-Octen-3-ol 982 980 1461 57-72,43,81,85,99 MS,RT 19 Phenol (Standard) 983 990 2004 94,66,65,39 MS,RT 20 Benzylalkohol 1037 1050 1876 108,107,79,77 MS,RT 21 4,6-Dimethyl-heptan-2-ol ? 1055 1054 43,57,69,85,45,87,126,144 MS 22 Linalool 1099 1106 1555 71,93-41,55,80-121,136 MS,RT 23 Phenylethanol 1111 1135 1910 91,92,122,65 MS,RT

24 α-Terpineol 1192 1211 1699 59,93,121 MS,RT 25 Methylsalicylat 1188 1219 1774 120,152,92 MS,RT 26 4-Vinylphenol 1230 1245 2395 120,91 MS,RT 27 Geraniol 1253 1262 41,69-93,111,123 MS,RT 28 (ein Monoterpenalkohol?) 1272 1287 59-68,67,71,79,94,152 29 4-Vinylguajacol 1306 1339 2205 135,150- MS,RT 30 Z-2,6-Dimethyl-2,7-Octadien-1,6-diol 1343 1361 2268 43,71,67,55,68 [32] 31 E-2,6-Dimethyl-2,7-Octadien-1,6-diol 1363 1379 2308 43,71,67,55,68 [32] 32 4-Hydroxy-Benzaldehyd ? 1417 121,122,65,103 MS 33 Vanillin 1441 151,152,81,109 MS,RT 34 Tyrosol 1473 107,138,77 MS,RT 35 p-Menth-1-en-7,8-diol 1469 1504 2509 59,79,94 [19] 36 Hydroxy-Benzoesäure 1590 121,138,93,65 MS 37 Vanillinsäure 1613 168,153,97,125 MS

38 2-(2-Butenyliden)-3,3-Dimethyl-5-2-oxopropyl-Tetrahydrofuran 1589 1626 43,125,109,82,208,95,151 [33]

39 3-OH-ß-Damascon 1602 1637 2533 69,43,121,175,193,208 [34] 40 3-OH-7,8-dihydro-ß-Jonol 1651 1692 2627 121,43,119,93,105,136,-212 [22],[35] 41 3-OH-5,6-epoxy-ß-Jonol 1661 1703 43,125,109,82,208,107,166 [35] 42 3-OH-5,6-epoxy-ß-Jonon 1680 1715 123,43,109,95 [36] 43 3-OH-ß-Jonon 1715 43,175,193 [37] 44 Vomifoliol 1780 1837 124-43,79,135,150,168 [22],[38] 45 p-Hydroxy-Zimtsäure 1869 164,147,119,91,65 MS 46 7,8-Dihydro-Vomifoliol 1845 1898 43,110,111,152,96,68,170 [22] 47 Ferulasäure 1928 194,179,133,77,105 MS

© by PSP Volume 24 – No 3. 2002 Advances in Food Sciences

113

OHOH

OH

OH

OHOH

OH

OHOH

OH OH

OHOH

OH

1 3 2OH

4

5

OH

13OH6

8 7 9 10

12 14 16 15

18 21

ABBILDUNG 3 - Enzymatisch freisetzbare aliphatische Alkohole des Hopfens (Nummerierung entspricht Tab. 4)

OHOH

OH

O-Me

OOH

OH

OH OH

CH3O

OH

CHO

OH

CH3O CHO

20 23 34 25

26 29 32 33

ABBILDUNG 4 - Enzymatisch freisetzbare aromatische und phenolische Hopfenaglycone (Nummerierung entspricht Tab. 4)

OH

OH

OH

OH

OH

OH OH

OH

OH

27 22 30 31 24 35

ABBILDUNG 5 - Enzymatisch freisetzbare Monoterpene des Hopfens (Nummerierung entspricht Tab. 4)

© by PSP Volume 24 – No 3. 2002 Advances in Food Sciences

114

OH

OH

OH

OHO OO

OH

OOH

OH

OOH

OH

O O40 41 38

46 44 39 ß-Damascenon

-H2O

ABBILDUNG 6 - Enzymatisch freisetzbare Nor-Carotinoide des Hopfens (Nummerierung entspricht Tab. 4).

TABELLE 5 - Mittels Sniffing-GC-MS in enzymatisch hydroly-sierten Hopfenextrakten eindeutig zugeordnete Geruchsstoffe.

Verbindung Geruch 3Z-Hexenal grün-grasig 3Z-Hexenol grün-grasig 1-Octen-3-ol Champignon 2-Phenylacetaldehyd süß-wachsig Linalool blumig-citrus 2-Phenylethanol blumig, Wein Geraniol citrusartig ß-Damascenon blumig-fruchtig, Apfelsaft Vanillin Vanille

DANKSAGUNG

Für die Bereitstellung der Hopfenproben danken wir Herrn Dr. M. Biendl, HHV D-84048 Mainburg. Für die Überlasung eines Hemicellulase-Präparates (�Rapidase F-64�) danken wir Herrn Dipl.-Ing. B. Heimann, DSM Food Specialities, D-44319 Dortmund. Frau E. Schütz danken wir für ihre bewährte analytische Mitarbeit.

LITERATUR

[1] Crouzet, J., Chassagne, D., Glycosidically bound volatiles in plant, in Ikan, R (Editor) Naturally Occuring Glycosides, Wi-ley&sons, Chichester, p.225-274 (1999)

[2] Arana, F., Action of a ß-Glucosidase in the curing of vanilla; Food Research 8: 343-351 (1943)

[3] Francis, M.J.O., Allcock, C., ß-D-Glucoside; occurrence and synthesis in rose flowers, Phytochemistry 8: 1339-1347 (1969)

[4] Cordonnier, R., Bayonove, C., Mise en évidence dans la baie de raisin, var. Muscat d`Alexandrie, de monoterpenes liés, révélables par une ou plusieurs enzymes du fruit. C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris, (Ser. D.), 278: 3387-3390 (1974)

[5] Stahl-Biskup, E., Intert, F., Holthuijzen, J., Stengele, M., Schulz, G., Glycosidically bound volatiles - A Review 1986-1991, Flavour and Fragrance Journal 8: 61-80 (1993)

[6] Goldstein, H., Ting, P., Navarro, A., Ryder, D., Water-soluble hop flavor precursors and their role in beer flavor, EBC Congress p. 53-62 (1999)

[7] Goldstein, H., Ting, P.L., Schulze, W.G., Murakami, A.A., Lusk, L.T.,Young, V.D., Methods of making and using puri-fied kettle hop flavorants, US-Patent 5,972,411 (1999)

[8] Engel, K.-H., Tressl, R., Formation of aroma components from nonvolatile precursors in passion fruit. J. Agric. Food Chem. 31: 998-1002 (1983)*

[9] Williams, P.J., Strauss, C.R., Wilson, B., Massy-Westropp, R.A.; Studies on the Hydrolysis of vitis vinifera monoterpene precursor compounds an model monoterpene ß-D-Glucosides rationalizing the monoterpene composition of grapes; J. Ag-ric. Food Chem. 30: 1219-1223 (1982)

[10] Sefton, M.A., Williams, P.J., Generation of Oxidation Arti-facts during the hydrolysis of norisoprenoid glycosides by fungal enzyme preparations. J. Agric. Food Chem. 39: 1994-1997 (1991)

[11] Humpf, H.U., Schreier, P., Bound aroma compounds from the fruit and the leaves of blackberry (Rubus lacinista L.) J. Agric. Food Chem. 39: 1830-1832 (1991)

[12] Knapp, H., Straubinger, M., Fornari, S., Oka, N., Watanabe, N., Winterhalter P., S-3,7-Dimethyl-5-octene-1,7-diol and re-lated oxygenated monoterpenoids from petals of rosa damas-cena Mill., J. Agric Food Cem. 46: 1966-1970 (1998)

[13] Wang, D., Yoshimura, T., Kubota, K., Kobayashi, A.; Ana-lysis of glycosidically bound aroma precursors in tea leaves. J. Agric. Food Chem. 48: 5411-5418 (2000)

© by PSP Volume 24 – No 3. 2002 Advances in Food Sciences

115

[14] van den Dries, J.M.A., Baerheim Svendsen, A., A simple me-thod for detection of glycosidic bound monoterpenes and o-ther volatile compounds occuring in fresh plant material, Fla-vour and fragrance Journal 4: 59-61 (1989)

[15] Humpf, H.U., Schreier, P., 3-Hydroxy-5,6-epoxy-ß-ionol ß-D-glucopyranoside and 3-Hydroxy-7,8-dihydro-ß-ionol ß-D-glucopyranoside: new C13 norisoprenoid glucoconjugates from sloe tree (Prunus spinosa L.) leaves. J. Agric. Food Chem. 40: 1898-1901 (1992)

[16] Williams, P.J., Strauss, C.R., Wilson, B., Massy-Westropp, R.A.; Use of C18 reversed-Phase liquid Chromatography for the isolation of monoterpene glycosides and nor-isoprenoid precursors from grape juice and wines, J. Chromatogr. 235: 471-480 (1982)

[17] Winterhalter, P., Bound Terpenoids in the juice of the purple passion fruit (Passiflora edulis Sims), J. Agric. Food Chem. 38: 452-455 (1990)

[18] Günata, Y.Z., Bayonove, C.L., Baumes, R.L., Cordonnier, R.E., The aroma of grapes I. Extraction and determination of free and glycosidically bound fractions of some grape aroma components. J. Chromatogr. 331: 83-90 (1985)

[19] Sakho, M., Chassagne, D., Crouzet, J., African Mango glyco-sidically bound volatile compounds, J. Agic. Food Chem. 45: 883-888 (1997)

[20] Versini, G., Dalla Serra, A., Dell´Eva, M, Scienza, A., Rapp, A., Evidence of some glycosidically bound new monoterpe-nes and norisoprenoids in grapes, in Bioflavour´87 (editor: Schreier, P.), deGruyter, Berlin, p 161-170 (1988)

[21] Chassagne, D., Boulanger, R., Crouzet, J.; Enzymatic hydro-lysis of edible Passiflora fruit glycosides; Food Chemistry 66: 281-288 (1999)

[22] Winterhalter, P., Schreier, P., Free and bound C13 norisopre-noids in Quince (Cydonia oblonga, Mill.) fruit. J. Agric. Food Chem. 36: 1251-1256 (1988)

[23] Schwab, W., Schreier, P., Simultaneous Enzyme catalysis Extraction: A versatile technique for the study of flavor pre-cursors. J.Agric. Food Chem. 36: 1238-1242 (1988)

{24] Wilson, B, Strauss, C.R., Williams, P.J., Changes in free and glycosidically bound monoterpenes in developing muscat grapes; J. Agric. Food Chem. 32: 919-924 (1984)

[25] Wu, P., Kuo, M-C., Ho, C.T., Glycosidically bound aroma compounds in ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe), J. Agric. Food Chem. 38: 1553-1555 (1990)

[26] Aryan, A.P., Wilson, B., Strauss C.R., Williams, P.J., The pro-perties of glycosidases of Vitis vinifera and a comparison of their ß-glycosidase activity with that of exogenous enzymes. An assessment of possible applications in enology. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 38: 182-188 (1987)

[27] Salles,C. Essaied, P., Chalier, P., Jallageas, J.C., Crouzet, J. Evidence and characterization of glycosidically bound volati-le components. Bioflavour´87 (editor: Schreier, P.), deGruy-ter, Berlin, p 145-160 (1988)

[28] Günata, Y.Z., Bayonove, C.L., Tapiero, C., Cordonnier, R.E., Hydrolysis of grape monoterpene ß-D-Glucosides by various ß-Glucosidases, J. Agric. Food Chem. 38: 1232-1236 (1990)

[29] Decker,C.H., Visser, J., Schreier, P. ß-Glucosidases from five black Aspergillus species: Study of their physico-chemical and biocatalytic properties. J. Agric. Food Chem. 48: 4929-4936 (2000)

[30] Günata, Y.Z., Bitteur, S., Brillouet, J.M., Bayonove, C.L., Cordonnier, R.E., Sequential enzymic hydrolysis of potenti-ally aromatic glycosides from grapes. Carbohydr. Res. 134: 139-149 (1988)

[31] Kollmannsberger, H., Nitz, S. Glykosidisch gebundene Aro-mastoffe in Hopfen (Humulus lupulus L.): 2. Derivatisierung mit Trifluoracetat, Adv. Food Sci. (CMTL) in Vorbereitung (2002)

[32] Winterhalter, P., Knapp, H., Straubinger, M., Fornari, S., Watanabe, N., Application of Countercurrent Chroma-tography to the Analysis of Aroma Precursors in Rose Flo-wers, in Mussinan, C.J., Morello, M.J. (Editors) Flavor Ana-lysis, ACS Symposium Series 705: 181-192 (1998)

[33] Neugebauer, W., Winterhalter, P., Schreier, P.; 2-(2-Butylidene)-3,3-dimethyl-5(2-oxopropyl)tetrahydrofuran: A new degradation product of 3-Hydroxy-5,6-epoxy-ß-ionol. J. Agric. Food Chem. 42: 2885-2888 (1994)