Aeronautics in the SLC States: Cleared for Takeoff

description

Transcript of Aeronautics in the SLC States: Cleared for Takeoff

THE SOUTHERN OFFICE OF THE COUNCIL OF STATE GOVERNMENTSPO Box 98129 | Atlanta, Georgia 30359

ph: 404/633-1866 | fx: 404/633-4896 | www.slcatlanta.orgSERVING THE SOUTH

Southern LegiSLative ConferenCe

of

the CounCiL of State governmentS

AERONAUTICS INTHE SLC STATES:CLEARED FOR TAKEOFFA REGIONAL RESOURCE FROM THE SLC

© Copyright February 2014

Sujit M. CanagaRetna Fiscal Policy ManagerSouthern Legislative ConferenceFebruary 2014

Introduction

Ageneration ago, a number of foreign auto- makers began establishing manufacturing op- erations in the South, in states represented by The Council of State Governments’ (CSG)

Southern Office, the Southern Legislative Conference (SLC). Until the last few decades of the 100-year history of automobile manufacturing in the United States, the in-dustry was heavily concentrated in the states surrounding the Great Lakes and across the border in Ontario, Canada. Leading the charge to the South was Nissan (announcing a facility in Smyrna, Tennessee, in April 1980), followed by Toyota (publicizing a facility in Georgetown, Kentucky, in December 1985). From these two foreign automakers, The Drive to Move South

* gathered steady speed and, by 2013, there were a dozen or more automobile manufacturers – Mercedes in Alabama, BMW in South Carolina, Nissan in Mississippi, Kia in Georgia and Volkswagen in Tennessee, * For a decade, the SLC has focused extensively on the economic im-pact of the auto industry in the South. In 2003, the SLC released a report entitled The Drive to Move South: The Economic Impact of the Au-

to Industry in the Southern Legislative Conference States. Since that time, the SLC has featured the topic in subsequent publications, presenta-tions to legislative bodies and other organizations, media interviews and as a discussion topic at SLC annual meetings. For more infor-mation on the SLC’s focus on the automotive industry, please see http://www.slcatlanta.org/Publications/index.php?topic=8.

to name a few – operating thriving assembly operations, generating billions of dollars in economic impact and em-ploying thousands of workers. In a move that parallels this important automotive industry trend, economic ana-lysts now are seeing another development: the increasing number of aeronautics companies that are locating, relo-cating or expanding their manufacturing operations in the South, a trend particularly discernible in the aftermath of the Great Recession.

Even though the South’s association with the aeronautics industry dates back to December 1903, when Orville and Wilbur Wright launched their box kite biplane (a contrap-tion largely constructed at their bicycle shop in Dayton, Ohio) from a windy outcrop in Kitty Hawk, North Caroli-na,1 in the ensuing century or so, the American aeronautics industry’s passenger jet manufacturing operations were largely confined to California (Los Angeles, Orange and San Diego Counties), Kansas (Wichita) and Washing-ton (Seattle). However, this localized concentration has gone through and is continuing to experience some ma-jor transformations. For instance, at the peak of the Cold War, 15 of the 25 largest aerospace companies in the Unit-ed States were located in Southern California; the number in California is now significantly smaller due to greater concentration in the industry – through a spate of merg-ers and consolidations that occurred in the 1990s – along Source: Cover photo courtesy of flickr user Nic Adler via Creative Commons License

2 AEROnAuTiCs in ThE sLC sTATEs: CLEARED FOR TAKEOFF

with closures and relocations to other parts of the United States.2 Similarly, Boeing had a decades-long manufactur-ing presence in Wichita, Kansas; however, in January 2012, Boeing announced that it would shutter its large Wichi-ta complex and move production to Oklahoma and Texas, both SLC states.3

Also, in Washington, in early January 2014, Boeing workers, in the narrowest of margins (51 percent to 49 percent), approved an eight-year contract extension with the company that assured production of Boeing’s new 777X aircraft in the Puget Sound area.4 (The current 777 is a long-range, twin-aisle aircraft that carries 365 passengers; the new 777X would be one-fifth more fuel-efficient and carry 400 passengers.) In November 2013, Boeing workers had rejected a similar contract with the company on the grounds that it included a pension freeze, increased healthcare costs and other cutbacks. However, Boeing workers shifted their stance, calling for a second vote on the issue, when Boeing solicited offers from other states to build the new 777X, a development that resulted in some 22 states expressing interest in hosting the multi-billion dollar project. The real danger that Boeing would

Table of ContentsIntroduction ........................................................................................ 1

A Word on Organization .............................................................................3Why the Move? ................................................................................ 4

Southern Workforce Development Programs ................................4Economies of Scale and Clustering .........................................................4Tax Incentives ....................................................................................................5Additional Factors ............................................................................................5

Industry Statistics ............................................................................6

Table 1: Annual Rate of Exports ..........................................................6Exports ....................................................................................................................6

Table 2: State Aerospace Exports .........................................................7Private Investment ...........................................................................................8

Table 3: Private Fixed Investment ......................................................8Figure 1: Private Fixed Investment.................................................. 10

Manufacturing Establishments ................................................................8Table 4: Aerospace Manufacturing Establishments ..................9

Employment ..................................................................................................... 10Table 5: Aerospace Manufacturing Employees ........................ 11Table 6: Top 10 States by Aerospace Job Growth .................... 12

Workforce Development ..........................................................13

Alabama ............................................................................................................... 14Robotic Technology Park Program ................................................ 14

Missouri .............................................................................................................. 14South Carolina ................................................................................................. 14

SC Manufacturers Alliance 2013 Legislative Agenda ............ 15Tennessee ........................................................................................................... 15

Selected Commercial Aircraft Manufacturers ...............16

Airbus ................................................................................................................... 16Boeing ................................................................................................................... 17Gulfstream ......................................................................................................... 20Spirit AeroSystems ........................................................................................ 21Honda Aircraft Company ......................................................................... 22GE Aviation ...................................................................................................... 23

North Carolina ............................................................................................ 23Mississippi ..................................................................................................... 23

UTC Aerospace Systems ............................................................................ 24Embraer ............................................................................................................... 24

Melbourne ..................................................................................................... 25Jacksonville ................................................................................................... 25

Dassault Falcon................................................................................................ 25Rolls-Royce ....................................................................................................... 26

Virginia ........................................................................................................... 27Mississippi ..................................................................................................... 27

Aeronautic Developments in Selected SLC States ....... 28

Alabama ............................................................................................................... 28Arkansas .............................................................................................................. 29Florida .................................................................................................................. 29

Figure 2: Florida’s Aviation & Aerospace Cluster .................... 30Georgia ................................................................................................................. 31Kentucky ............................................................................................................ 32Mississippi .......................................................................................................... 32Missouri .............................................................................................................. 33Texas ..................................................................................................................... 33

Conclusion .........................................................................................34

Endnotes .............................................................................................36

have relocated the manufacture of this airplane to another state, potentially costing the Puget Sound area more than 10,000 jobs, triggered the second vote by Boeing work-ers. Prior to the first vote by Boeing workers, in an effort to woo Boeing and ensure the production of the plane in the area, the Washington Legislature approved a $9.7 bil-lion multi-decade (through 2040) incentive package for the company. Bolstered by the incentive package provid-ed by the Washington Legislature and the second vote by Boeing workers supporting a new contract, Boeing con-firmed that the final assembly of the planned 777X will occur in the Puget Sound area. The company also indicat-ed that it will not be hit by any machinist strikes through 2024. The fact that Boeing was serious about considering locations other than the Puget Sound area† to manufac-ture the new 777X was another indication that the locus

† In 2009, amidst much fanfare, Boeing announced the opening of its first Southern manufacturing facility in Charleston, South Car-olina, geared toward building the 787 Dreamliner aircraft. South Carolina, along with nearly two dozen states, including California, Utah, Texas, Missouri, Alabama, Georgia, Arizona and North Car-olina, expressed strong interest in being the site for the new 777X Boeing production facility.

AEROnAuTiCs in ThE sLC sTATEs: CLEARED FOR TAKEOFF 3

Despite the colossal challenges faced by America’s manu-facturing sector in recent decades, the aeronautics sector has proven to be one of the most resourceful and resilient on the contemporary economic scene. In fact, reports in-dicate that even though U.S. manufacturing employment shrank by 22 percent between 2002 and 2012, the aeronau-tics/aerospace sector grew 7 percent over the same period. Experts maintain that there are some 500,000 workers di-rectly employed in aerospace manufacturing.5 Moreover, industry experts forecast that the aeronautics sector will experience substantial growth in coming years. For in-stance, Boeing projects demand for nearly 32,000 new aircraft by 2031; given that presently there are fewer than 20,000 aircraft in service, worldwide, the need to manufac-ture fleets of new planes remains tremendous.6 Similarly, Airbus projects demand for 19,200 new jets of all types, amounting to $1.4 trillion, by 2030.7 As a result, policy-makers in a number of SLC states have worked arduously to court an increasing number of aeronautics companies, ranging from industry titans such as Boeing and Airbus to smaller operations, such as Honda Aircraft and SpiritAero-Systems, to myriad parts suppliers such as Adex Machining Technologies and GKN Aerospace, to their locales.

Boeing facility, but Missouri was the only state – along with Wash-ington – that convened a special session in December 2013 to craft an incentive package for Boeing. However, as mentioned, Boeing workers conducted a second vote and agreed to terms laid out by Boeing, a fact that resulted in Boeing confirming that it would carry out final assembly of the new 777X in the Puget Sound area.

A Word on OrganizationIn terms of the organizational structure, this Regional Re-source is broken into five sections. Section one explores some of the factors prompting aircraft manufacturers -- large, medium and small -- to consider and, in many in-stances, follow through on plans to locate to the SLC re-gion. Section two investigates the fiscal health of the aeronautics sector and its role in Southern state economies (and, largely, for all 50 states) by probing a range of statis-tical data, including figures on production or output (rep-resented by exports), investment in equipment, and em-ployment. Section three details Southern state efforts to expand their workforce development programs as a spe-cific response to the technologically proficient workers re-quired to perform the advanced manufacturing work at these aeronautics companies. The final two sections pro-vide information on selected commercial aircraft manufac-turers that have either recently set up manufacturing oper-ations in the SLC states or are in the process of expanding ongoing operations and selected aeronautics topics from around the SLC region. Boeing 787 flight test. Photo courtesy of Boeing MediaRoom.

of America’s aeronautics center was shifting from former strongholds like Washington.

In light of these recent events, industry analysts are honing in on a critical, emerging trend: the movement by many aeronautics companies to relocate their assembly and man-ufacturing operations away from the three states that previously dominated the sector to multiple locations in the South.

For policymakers in the South, the potential to capture a portion of the burgeoning aeronautics/aerospace sector is a huge opportunity given the enormous economic opportu-nities at stake. Consequently, Southern policymakers have moved with great alacrity to ensure that their particular state remains a frontrunner in securing the commitment of these aeronautics companies looking to relocate. A prime example is the emergency special legislative session that was called in Missouri in early December 2013 so that Gov-ernor Jay Nixon and members of the General Assembly could debate and reach consensus on a $150 million annual economic incentive package geared specifically toward at-tracting Boeing and the production of the 777X to the state.‡

‡ The Missouri special session was in response to the November 2013 failed talks between Boeing union workers and Boeing in Washing-ton over manufacturing the 777X aircraft in the Puget Sound area and Boeing’s indication that it would consider alternate locations (both in the United States and overseas) for the project. A num-ber of other states also expressed great interest in hosting the new

4 AEROnAuTiCs in ThE sLC sTATEs: CLEARED FOR TAKEOFF

There is a definitive trend in progress when, in the space of less than a decade, Boeing sets up a multi-billion dollar assembly operation in Charleston, South Carolina; Airbus announces its first Amer-

ican manufacturing facility in Mobile, Alabama, designed to manufacture the A319, A320 and A321 aircraft; Gulf-stream publicizes a $500-million, seven-year expansion of its Savannah, Georgia, facility; North Carolina boasts a bur-geoning aeronautics cluster with SpiritAeroSystems (the world’s largest independent supplier of commercial airplane assemblies and components) opening a manufacturing facil-ity in Lenoir County, Honda Aircraft expands its facilities and land usage in Guilford County and GE Aviation enlarg-es its assembly plant in Durham County; Virginia advertises that Rolls-Royce, the famed global power systems company, launched a new advanced manufacturing facility in Prince George County; Dassault Falcon Jets increases the size of its completion center in Little Rock, Arkansas, the second such expansion in five years; and Embrarer, the Brazilian aero-space conglomerate that produces commercial, military, and executive aircraft and provides aeronautical services, ex-pands its Melbourne, Florida, operation to manufacture the company’s Legacy 450 and 500 planes.

Economic development and aeronautics experts tracking the migration of these aeronautics companies to the South highlight a number of factors propelling this movement. Interestingly, several circumstances that drove foreign auto-makers to locate in the South also loom large when probing the location decisions influencing the aeronautics companies.§

Southern Workforce Development ProgramsIn prior decades, the aeronautics industry was considered “uniquely complex” and “technically rigorous,” a situation that demanded a steady stream of engineers and techni-cians to staff the positions. At the time, California, Kansas and Washington had educational institutions that provided

§ The section on the factors influencing the aeronautics industry to locate and expand in the South draws on parallels from the auto-motive sector as contained in CanagaRetna, Sujit M., “Paving the Road to Prosperity: Auto Industry in the South Faring Well in Contracting National Economy,” State News, The Council of State Governments, August 2008.

the aeronautics companies with their staffing requirements. However, “modern production technologies, training and better education have narrowed the gap with other sectors, prompting bids from communities that aviation firms over-looked until recently.”8 Further, Southern states have taken aggressive steps to design workforce development programs in aeronautics and aviation to promote themselves as vi-able manufacturing options to the industry. For instance, the Alabama Industrial Development Training program (AIDT) runs aviation-industry-specific facilities at the Ro-botic Technology Park in Tanner, Alabama.9 Among other benefits, the facility provides no-cost training in the fields of automation and robotics for workers to be employed in aeronautics companies such as Airbus. According to Airbus Americas Chairman Allan McArtor, the company’s decision to locate its first North American manufacturing facility in Mobile was influenced by the workforce.10

Economies of Scale and ClusteringExperts point to the economies of scale and cascade of ad-ditional benefits created by the cluster effect, with the growing number of aeronautics plants and hundreds of parts suppliers in close proximity to each other, as an impe-tus for the growth of the industry in the South. Researchers such as Harvard University’s Michael E. Porter have car-ried out extensive analysis on the cluster effect, i.e., “the positive spillovers across complementary economic activ-ities providing an impetus for agglomeration: the growth rate of an industry within a region may be increasing in the size and ‘strength’ (relative presence) of related economic sectors.”11 Given the fact that the aeronautics industry is one of the largest high-technology employers in advanced countries, other researchers have assessed the specific role of aerospace clusters and their potential for local and global knowledge spillovers.12 According to this research, while the aerospace cluster demonstrates a number of industry-specific characteristics when compared with automobile, biotechnology and information technology regional inno-vation systems, one prominent, overlapping feature they all share is the trend of large firms dominating the cluster and representing a magnet for suppliers to locate in the vi-cinity. The example of Boeing in South Carolina supports this trend, with the aeronautics giant serving as a magnet

WHy THE MOvE?Honda Aircraft Company campus at Piedmont Triad International Airport, Greensboro, North Carolina. Photo courtesy of Honda Aircraft Company.

AEROnAuTiCs in ThE sLC sTATEs: CLEARED FOR TAKEOFF 5

to attract local suppliers. Specifically, in 2012, a few years after opening its South Carolina location, Boeing worked with 345 suppliers and vendors in the state.13 One such company is Phoenix, located in Bamberg, South Carolina. According to Phoenix President Robert Hurst, the compa-ny’s tie to Boeing is through General Electric, which makes the GEnx engine, one of two engines that are used to power the 787 Dreamliner. Another such supplier company is Ad-ex Machining Technologies, located in Greenville, South Carolina, which manufactures precision machined compo-nents for aerospace, defense and energy industries. Adex, which has 50 employees, is a certified Boeing vendor and has been selected for Boeing’s mentor protégé program, which places the company on the fast track to become a first-tier supplier to Boeing, a certification that could ad-vance the company to new heights.14 A similar case can be made with the supplier network that has begun setting up operations in the wake of Airbus’ decision to locate its first North American manufacturing facility in Mobile, Alabama. A short while after the July 2012 Airbus an-nouncement, Safran Engineering Services (a unit within the French aerospace conglomerate, Safran Group) indi-cated that it was establishing an engineering supporting facility, also in Mobile, creating up to 50 jobs to serve as a supplier to Airbus.15 In 2003, St. Louis, Missouri-based LMI Aerospace (a leading supplier of structural components, as-semblies and kits to the aerospace industry) opened a plant in Savannah, Georgia, to service Gulfstream Aerospace, also based in Savannah.16 LMI Aerospace’s 161,000-square-foot facility, as of July 2013, after an acquisition and an expansion, has 155 employees.

Tax IncentivesSouthern states extend attractive incentive packages, in-cluding tax breaks, the previously referenced worker training programs, an abundant labor pool and the ability to train a workforce that has not worked in the aeronautics sector in the past. In terms of incentive packages, in April 2013, Boeing announced that it was expanding its South Carolina location with an additional $1 billion investment, a move that would create another 2,000 direct jobs over the next several years. In turn, the state of South Carolina is providing $120 million in incentives for upfront costs such as utilities and site preparation at the company’s North Charleston manufacturing complex.17 Similarly, in July

2012, when Airbus announced its $600 million assembly plant in Mobile, Alabama, the state indicated it would pro-vide $125 million, and local governments would provide an additional $33.6 million, for a total incentive package of nearly $159 million.18

Additional FactorsCompanies also are considering a number of additional ad-vantages of the South during the site selection process:

» The ability to construct new manufacturing facilities incorporating all the latest technologies more efficient-ly and effectively at a Southern location, as opposed to reconfiguring older assembly plants in the states that pre-viously dominated the aeronautics sector;

» The low or nonexistent rates of unionization and the negli-gible level of interest among Southern workers to unionize;19

» The extremely cost effective intermodal transportation network in the region, spanning railways, highways, air-ports and, most importantly, ports. With regard to ports, when Airbus announced its Mobile manufacturing facility, company officials cited the Port of Mobile as an instru-mental factor in its location decision. Officials indicated that certain partially completed sections of the aircraft – from cockpit to tail – will be shipped to the Port by barge from Airbus’ European manufacturing locations and used in the assembly of the aircraft at the Alabama location;

» A series of additional characteristics that make the South attractive for aeronautics companies, including the weath-er, reduced cost-of-living, lower or no personal income taxes, free or inexpensive property on which to build, along with other attractive quality of life attributes; and

» Finally, a phenomenon that appears to be unique to the aeronautics sector: the potential for highly lucra-tive defense-related federal government contracts being enhanced by having a presence in an array of states as opposed to concentrating assembly operations in a few select states, as was the case in prior decades. “Spreading their operations out also can be a way to gain political influence in an industry where government plays an im-portant role both as a regulator and customer.”20

Securing or expanding a major aeronautics company, whether it is an Airbus or SpiritAeroSystems or Dassault Falcon, generates an array of direct, indirect and induced economic flows to the city, state and even the entire region. In addition, the “halo” effect, i.e., the considerable boost to a city and state’s image and global competitiveness as a result of landing a major and highly prestigious aeronautics com-pany, also generates an immense degree of positive media attention and economic benefits.

“[Airbus] was encouraged by the auto industry’s success in Alabama because its manufacturing aspect is a trained skill similar to that of aircraft assembly.”

- Allan McArtor, Chairman, Airbus Americas

6 AEROnAuTiCs in ThE sLC sTATEs: CLEARED FOR TAKEOFF

Turbine manufacturing process at an Auburn, Alabama, GE Aviation jet engine components factory. Photo courtesy of GE Aviation.

While there is growing evidence of mul-tiple aeronautics companies setting up manufacturing operations in the SLC states, a review of selected statistical

data is essential to determine the relative health of the in-dustry, particularly with regard to production or output (represented by exports), investment in equipment and employment. This analysis will facilitate more meaning-ful conclusions on the continued strength of the economy in future decades and the role the industry will play across the states, especially the SLC region.

ExportsOne such data set involves the figures related to the ex-port of civilian aircraft, engines and parts. While there has been a great deal of interest and focus at every level of government (federal, state and local) to expand ex-ports in recent years, the export of aircraft and related items represents an area where the United States enjoys a clear dominance in global circles. U.S. transportation ex-ports, which include aircraft exports, continue to rank at the top of a listing of all U.S. exports for the last several years (2007 to 2012); when this category does not rank at the very top, it often is in the top three. Given that the focus of this Regional Resource is the passenger or civil-ian aircraft segment within the industry, these numbers provide a clear signpost of the growth trajectory of the sector. Table 1 provides these details for the last decade along with year-to-date information for 2013.

INDUSTRy STATISTICS

Year Export Value

2002 $50.4

2003 $46.7

2004 $46.1

2005 $55.9

2006 $64.5

2007 $73.0

2008 $74.0

2009 $74.8

2010 $71.9

2011 $80.2

2012 $94.4

2013 (January - September) $105.7

Source: U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis (accessed November 11, 2013)

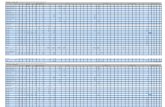

Table 1Seasonally Adjusted Annual Rate of Exports of Civilian Aircraft, Engines and Parts 2002 to 2013 (in billions US$)

State 2002 2007

Percent

Change

2012

Percent

Change

Percent Change,

2002- 2012

Year-To-Date

(Jan - Sept 2013)

United States (Total) 56,344,487,226 84,763,400,210 50% 105,839,451,836 25% 88% 85,904,714,534Washington 23,120,667,507 27,753,699,686 20% 37,110,551,093 34% 61% 32,677,539,557California 4,891,899,473 7,207,393,816 47% 7,994,835,882 11% 63% 7,122,563,049Connecticut 3,961,637,795 5,599,083,259 41% 6,981,781,182 25% 76% 5,984,801,782Georgia 991,433,194 2,997,814,005 202% 5,638,614,220 88% 469% 4,882,750,845Texas 2,124,533,645 5,302,862,373 150% 5,636,133,411 6% 165% 4,222,131,983Florida 2,233,475,975 3,397,443,031 52% 5,736,121,115 69% 157% 4,083,054,040Ohio 2,180,655,598 3,457,490,741 59% 5,663,256,001 64% 160% 3,985,063,081Kentucky 2,072,000,820 3,845,838,070 86% 3,834,815,372 0% 85% 3,812,317,004Arizona 2,053,205,239 2,864,454,573 40% 2,603,325,732 -9% 27% 2,228,575,803New York 2,669,046,660 2,584,090,234 -3% 2,511,750,391 -3% -6% 1,599,232,555Arkansas 442,946,418 1,151,184,939 160% 1,867,421,182 62% 322% 1,350,808,141Kansas 1,200,799,748 3,450,374,783 187% 2,101,356,675 -39% 75% 1,317,800,725Indiana 308,538,771 825,828,303 168% 1,698,612,730 106% 451% 1,160,615,596Pennsylvania 363,999,680 587,743,737 61% 989,708,243 68% 172% 1,096,110,543North Carolina 193,776,724 854,449,276 341% 1,130,803,736 32% 484% 988,700,002New Jersey 997,943,571 1,384,705,940 39% 1,037,153,644 -25% 4% 800,568,528Tennessee 562,443,680 953,429,806 70% 1,231,582,663 29% 119% 796,926,281Illinois 513,459,408 1,404,548,618 174% 1,031,654,626 -27% 101% 678,327,920Michigan 245,162,596 510,067,153 108% 953,303,953 87% 289% 637,628,086Massachusetts 275,898,771 616,244,496 123% 787,552,174 28% 185% 592,870,942Alabama 266,184,587 338,927,534 27% 691,774,567 104% 160% 504,680,205Virginia 466,961,045 983,727,009 111% 1,075,883,880 9% 130% 497,704,918Minnesota 271,342,233 533,680,586 97% 457,733,294 -14% 69% 493,604,104Maryland 481,424,535 729,932,435 52% 652,654,285 -11% 36% 452,231,262Oklahoma 232,706,465 291,007,151 25% 504,029,922 73% 117% 434,377,646Oregon 280,332,161 388,793,691 39% 625,539,685 61% 123% 403,082,835South Carolina 92,457,229 218,802,899 137% 213,753,828 -2% 131% 391,527,665Missouri 96,448,987 1,316,632,495 1265% 703,891,926 -47% 630% 341,239,344Utah 130,939,259 306,307,314 134% 390,157,012 27% 198% 250,216,252D.C. 531,943,543 575,414,467 8% 501,757,387 -13% -6% 243,609,955Wisconsin 106,577,493 293,121,279 175% 343,352,710 17% 222% 240,223,595Iowa 40,598,534 356,061,442 777% 326,114,016 -8% 703% 213,363,613Colorado 154,877,122 144,085,795 -7% 176,641,991 23% 14% 199,320,869Louisiana 212,477,155 254,119,969 20% 226,145,060 -11% 6% 179,304,430West Virginia 107,757,591 169,015,981 57% 282,741,465 67% 162% 150,541,816Maine 63,744,714 76,728,091 20% 253,731,689 231% 298% 137,088,452Mississippi 26,160,448 54,842,521 110% 216,458,328 295% 727% 127,386,191Hawaii 234,867,501 61,904,062 -74% 307,884,386 397% 31% 105,392,845Nevada 29,193,085 145,415,000 398% 99,692,200 -31% 241% 98,339,978Unallocated 911,195,031 226,166,193 -75% 119,491,425 -47% -87% 75,256,453New Mexico 32,583,223 79,594,322 144% 65,664,896 -18% 102% 70,207,754Delaware 11,576,008 71,185,721 515% 165,224,082 132% 1327% 53,374,865New Hampshire 22,983,040 54,333,892 136% 61,719,175 14% 169% 45,761,193Vermont 53,300,034 62,240,260 17% 66,544,069 7% 25% 43,615,244North Dakota 21,943,242 14,124,669 -36% 26,852,454 90% 22% 31,598,386Idaho 4,002,202 18,619,988 365% 537,991,212 2789% 13342% 30,563,597Alaska 23,742,493 35,592,734 50% 72,752,866 104% 206% 30,316,293Nebraska 20,333,078 127,584,436 527% 74,919,669 -41% 268% 12,475,682Montana 1,795,640 23,455,498 1206% 11,512,586 -51% 541% 11,873,747Rhode Island 4,755,748 10,307,222 117% 7,455,258 -28% 57% 6,581,351Puerto Rico 2,429,520 3,296,356 36% 11,215,112 240% 362% 4,219,093South Dakota 1,412,229 48,451,445 3331% 25,227,802 -48% 1686% 3,561,456Wyoming 1,916,778 986,291 -49% 2,473,971 151% 29% 1,750,282

Source: U.S. Department of Commerce, International Trade Administration (accessed November 18, 2013)

Table 2 State Aerospace Exports 2002 to 2012 and First Three Quarters of 2013 (in US$)

8 AEROnAuTiCs in ThE sLC sTATEs: CLEARED FOR TAKEOFF

According to Table 3, while there have been some years during the 2002-2012 review period when there were no year-over-year increases in private fixed investment in the aircraft sector, the last three years (2010 to 2012) saw steady increases. In fact, between 2002 and 2012, there were de-clines in four years, all years when the effects of the 2001 recession and the Great Recession were most severe. Be-tween 2002 and 2012, the increase in investment from $27.2 billion to $34.2 billion signaled a growth rate of 26 percent, a noteworthy number. This rate also reflects the encouraging signs that America’s manufacturing sector is experiencing a renaissance, albeit a muted one;¶ an indication that steady fixed investments will lead to greater output in the sector. Figure 1 also presents private fixed investment in aircraft manufacturing for the period 2009 through 2012, a period of consistent growth.

Manufacturing EstablishmentsAnother statistical indicator of the relative health of the aeronautics sector involves the number of private, aerospace product and parts manufacturing establishments in the states over the past decade (2002 to 2012). The data featured in Ta-ble 4 involves the same sub-categories that were featured in Table 2: aircraft manufacturing; aircraft engine and en-

¶ For greater details on the American manufacturing renaissance, please see CanagaRetna, Sujit, M., “Workforce Development In the SLC States,” July 2013, http://www.slcatlanta.org/Publications/

EconDev/workdev_web.pdf.

Year Export Value

2002 $27.2

2003 $20.0

2004 $23.3

2005 $22.5

2006 $21.4

2007 $28.3

2008 $29.4

2009 $17.7

2010 $22.3

2011 $25.5

2012 $34.2

Source: U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis (accessed November 11, 2013)

Table 3Private Fixed Investment in Aircraft Manufacturing 2002 to 2012 (in billions US$)

Table 1 documents the impressive performance of civil-ian aircraft, engines and parts exports. From $50.4 billion in 2002, the sector steadily increased in almost every year over the next 11 years (experiencing a slight 1 percent de-cline between 2003 and 2004) and over the first nine months of 2013, and is on track to equal $105.7 billion for the year (seasonally adjusted).

Further exploring the statistics related to exports allows us to review a breakdown by state. Table 2 fea-tures this information for the 2002 to 2012 period and the first three quarters of 2013. The data featured in Table 2 refers to exports in the larger aerospace prod-uct and parts manufacturing category that includes the following sub-categories: aircraft manufacturing; air-craft engine and engine parts manufacturing; other aircraft parts and auxiliary equipment manufactur-ing; guided missile and space vehicle manufacturing; guided missile and space vehicle propulsion unit and propulsion unit parts manufacturing; other guided missile and space vehicle parts; and auxiliary equip-ment manufacturing.

As apparent in Table 2, aerospace exports fared extremely well in the 2002 to 2012 decade, with the number increas-ing from $56.3 billion in 2002 to $105.8 billion in 2012, an increase of 88 percent. At the mid-point in the decade, 2007, aerospace exports already were a remarkable $84.8 billion, an improvement of 50 percent from 2002. More impressively, at the end of the first three quarters in 2013, total aerospace exports amounted to nearly $86 billion, some 81 percent of the amount reached for the entire year in 2012. Hence, it is very likely that when aerospace exports for the entire 2013 calendar year are tabulated, they will exceed the level reached in 2012. Further inves-tigation into the performance of the SLC states in terms of aerospace exports allows for several conclusions: for the 2002 to 2012 period, only one state (Louisiana) experi-enced a single digit growth rate; a second state (Kentucky) experienced double digit growth, while the remaining 13 states all saw triple digit growth rates. Florida and Georgia were the two SLC states with the largest aero-space exports, with $5.7 billion and $5.6 billion in 2012, respectively.

Private InvestmentAnother statistical indicator worthy of review is private fixed investment in all aspects of aircraft manufacturing, a number that would signify how confident decision makers in the sector are about its future growth potential. Table 3 outlines this indicator.

State 2002 2007 2012

Percent Change

2002-2007

Percent Change

2007-2012

Percent Change

2002-2012

United States (Total) 2,244 2,323 2195 4% -6% -2%California 633 634 587 0% -7% -7%Florida 171 219 302 28% 38% 77%Texas 220 250 226 14% -10% 3%Washington 187 194 170 4% -12% -9%Connecticut 156 154 163 -1% 6% 4%Kansas 147 143 149 -3% 4% 1%Georgia 51 81 147 59% 81% 188%Ohio 111 115 123 4% 7% 11%Arizona 135 131 122 -3% -7% -10%New York 87 107 97 23% -9% 11%Oklahoma 65 80 67 23% -16% 3%Michigan 64 67 66 5% -1% 3%Pennsylvania 59 74 61 25% -18% 3%Utah 41 51 55 24% 8% 34%Missouri 48 43 49 -10% 14% 2%North Carolina 25 31 49 24% 58% 96%Alabama 41 46 48 12% 4% 17%Illinois 34 45 45 32% 0% 32%Indiana 41 40 44 -2% 10% 7%Oregon 42 43 41 2% -5% -2%Colorado 37 41 36 11% -12% -3%Tennessee 28 21 33 -25% 57% 18%Maryland 29 32 32 10% 0% 10%Massachusetts 31 33 32 6% -3% 3%Virginia 30 35 31 17% -11% 3%Minnesota N/A 28 29 N/A 4% N/AArkansas 33 27 27 -18% 0% -18%Kentucky 13 13 26 0% 100% 100%New Jersey 23 23 25 0% 9% 9%Idaho 20 26 24 30% -8% 20%South Carolina N/A 10 24 N/A 140% N/ALouisiana 15 17 21 13% 24% 40%New Mexico 10 15 21 50% 40% 110%Wisconsin 25 22 19 -12% -14% -24%Nevada N/A 10 13 N/A 30% N/ANew Hampshire 10 10 12 0% 20% 20%West Virginia 15 13 12 -13% -8% -20%Mississippi 7 11 10 57% -9% 43%Nebraska N/A 10 10 N/A 0% N/AVermont N/A 7 9 N/A 29% N/AMaine N/A 4 8 N/A 100% N/AAlaska 6 8 7 33% -13% 17%Montana 12 8 7 -33% -13% -42%Delaware N/A 3 6 N/A 100% N/AIowa N/A 6 6 N/A 0% N/ANorth Dakota 7 5 5 -29% 0% -29%South Dakota 7 9 4 29% -56% -43%Wyoming N/A 5 4 N/A -20% N/AHawaii N/A 1 2 N/A 100% N/ARhode Island N/A 1 N/A N/A -100% N/A

Source: U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics (accessed November 13, 2013)

Table 4 Private Aerospace Product and Parts Manufacturing Establishments by State 2002-2012

10 AEROnAuTiCs in ThE sLC sTATEs: CLEARED FOR TAKEOFF

gine parts manufacturing; other aircraft parts and auxiliary equipment manufacturing; guided missile and space vehicle manufacturing; guided missile and space vehicle propulsion unit and propulsion unit parts manufacturing; other guid-ed missile and space vehicle parts; and auxiliary equipment manufacturing. Although the totals for each year presented in Table 4 include data for both aircraft manufacturing and guided missile and space vehicle manufacturing, except for Alabama, California, Texas, and a single year in Virginia, the differences in these categories are negligible.

As evident in Table 4, even though there was a decline (-2 percent) in the number of private aerospace product and parts manufacturing entities in the United States between 2002 and 2012, and for the more recent 2007 to 2012 peri-od (-6 percent), a number of the SLC states fared well. Of the 50 states, there were 11 states for which data was un-available for the three years selected in the decade under review (2002 - 2012).** An additional 11 states saw declines in the number of aerospace manufacturing facilities dur-ing the review decade. Twenty-eight states saw an actual increase in the number of such establishments. Of the 11 states that saw declines, two were SLC states (West Virgin-ia and Arkansas); of the 28 states that saw an increase, four ** Data for these states did not meet Bureau of Labor Statistics or state agency disclosure standards. One possible explanation for these omissions is that the numbers were so small that it would have al-lowed for the identification of specific individuals and/or companies.

experienced single digit increases (Missouri, Texas, Okla-homa and Virginia) while the remaining nine SLC states also saw at least double digit increases. In fact, two SLC states (Kentucky and Georgia) experienced triple digit in-creases in the decade. Georgia’s 188 percent increase was the highest in the nation. Finally, even though informa-tion for South Carolina was only available for the 2007 to 2012 period, the state more than doubled its number of aerospace establishments in the past five years.

EmploymentAnother important statistical indicator of the health of the industry involves reviewing employment patterns during the past decade (2002 to 2012). Once again, the focus is on the number of private sector jobs created by the aerospace prod-uct and parts manufacturing sector. As with Table 4 that reviewed the number of establishments, Table 5 includes air-craft (engines, engine parts, other parts, auxiliary equipment) and all items related to guided missiles and space vehicles.

As demonstrated in Table 5, there was no data available for all the years in the review decade (2002 - 2012) for 13 states. An additional 14 states saw a decline in employ-ment in the aerospace sector between the two ends of the review decade, including five SLC states (Louisiana, Vir-ginia, Tennessee, Arkansas and Alabama) along with two states that saw no change and zero growth (Florida, an SLC state, was one of the two states). Finally, the remain-

Figure 1 Private Fixed Investment in Aircraft Equipment and Software

Source: National Income and Product Accounts Tables, Bureau of Economic Analysis, U.S. Department of Labor (accessed February 7, 2013)

State 2002 2007 2012

Percent Change

2002-2007

Percent Change

2007-2012

Percent Change

2002-2012

United States (Total) 302,698 293,955 274,324 -3% -7% -9%Washington 75,653 80,036 94,224 6% 18% 25%California 79,425 71,971 70,465 -9% -2% -11%Texas 41,080 47,871 47,940 17% 0% 17%Kansas 40,806 41,092 32,409 1% -21% -21%Connecticut 32,072 31,609 30,352 -1% -4% -5%Arizona 28,768 27,426 26,652 -5% -3% -7%Georgia 9,901 19,012 22,002 92% 16% 122%Florida 19,023 19,639 19,041 3% -3% 0%Ohio 15,212 16,145 16,124 6% 0% 6%Missouri 13,556 14,560 14,235 7% -2% 5%Alabama 13,044 12,941 12,514 -1% -3% -4%Pennsylvania 8,310 8,891 11,805 7% 33% 42%Massachusetts 13,158 11,899 11,600 -10% -3% -12%Indiana 7,320 7,104 7,181 -3% 1% -2%Colorado 6,841 7,757 6,824 13% -12% 0%New York 6,354 6,858 6,717 8% -2% 6%Oklahoma 3,701 5,226 6,218 41% 19% 68%Utah 6,634 8,359 5,926 26% -29% -11%South Carolina N/A 866 5,867 N/A 577% N/AMaryland 3,078 4,938 5,463 60% 11% 77%North Carolina 2,105 3,521 4,601 67% 31% 119%Michigan 4,782 3,037 3,758 -36% 24% -21%Arkansas 4,045 3,722 3,228 -8% -13% -20%Oregon 2,237 2,845 3,122 27% 10% 40%Illinois 2,583 2,697 2,940 4% 9% 14%Kentucky 1,797 2,803 2,938 56% 5% 63%West Virginia 2,085 2,694 2,364 29% -12% 13%Tennessee 3,033 2,157 2,137 -29% -1% -30%New Jersey 1,540 1,408 1,653 -9% 17% 7%Virginia 3,289 1,446 1,599 -56% 11% -51%Louisiana 3,103 2,838 1,341 -9% -53% -57%Vermont N/A N/A 1,332 N/A N/A N/ANew Hampshire 887 1,134 1,241 28% 9% 40%Wisconsin 1,144 1,128 1,158 -1% 3% 1%New Mexico 1,089 2,267 1,063 108% -53% -2%Mississippi 509 754 882 48% 17% 73%Minnesota N/A N/A 824 N/A N/A N/ANorth Dakota 664 N/A 605 N/A N/A -9%Nevada N/A 728 552 N/A -24% N/ANebraska N/A 390 455 N/A 17% N/ADelaware N/A N/A 429 N/A N/A N/AIdaho 125 258 309 106% 20% 147%Montana 105 145 177 38% 22% 69%South Dakota 79 144 86 82% -40% 9%Wyoming N/A 74 57 N/A -23% N/AAlaska 29 39 N/A 34% N/A N/AHawaii N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/AIowa N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/AMaine N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/ARhode Island N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A

Source: U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics (accessed November 13, 2013)

Table 5 Private Aerospace Product and Parts Manufacturing Employees by State 2002-2012

12 AEROnAuTiCs in ThE sLC sTATEs: CLEARED FOR TAKEOFF

number of aerospace establishments (from 51 in 2002 to 147 in 2012). Based on this information, the aerospace sector clearly has surfaced as a major economic booster to Georgia and regional economies. In terms of overall U.S. employment in the aerospace sector, paralleling the broader struggles faced by the American manufacturing sector in recent decades, there was an overall decline in the number of employees both between 2002 and 2012 (-9 percent) and 2007 and 2012 (-7 percent).

A report prepared by Avalanche Consulting, an economic consulting outfit based in Austin, Texas, released in Febru-ary 2013 revealed very positive employment trends in the aerospace sector for South Carolina, North Carolina, Okla-homa and Georgia.21 Table 6 provides these details.

As noted in Table 6, South Carolina’s aerospace sector em-ployment grew by more than 600 percent between 2007 and 2012, a number that was largely influenced by the opening of the Boeing facility in North Charleston and its host of related suppliers. Specifically, there was a total of 4,961 new net jobs created in the sector between the second quarter of 2007 and 2012. Of the top 10 states experienc-ing the greatest increases in aerospace jobs in the five-year review period, four were in the SLC region and all signif-icantly exceeded the national growth rate (1.6 percent) in terms of job growth. In fact, North Carolina’s nearly 34 percent growth rate between 2007 and 2012 ranked the state second in the nation, after South Carolina.

State

Employ-

ment

Q2/2012

Net New

Jobs

Q2/2007-12

Growth

Q2/2007-12

United States (Total) 491,640 7,508 1.6%

South Carolina 5,771 4,961 612.5%

North Carolina 4,575 1,158 33.9%

Pennsylvania 11,779 2,922 33.0%

Michigan 3,742 744 24.8%

Washington 93,060 14,212 18.0%

Oklahoma 5,975 865 16.9%

Georgia 21,998 3,073 16.2%

Oregon 3,081 331 12.0%

Maryland 5,481 552 11.2%

Illinois 2,956 231 8.5%

Source: Avalanche Consulting (accessed November 19, 2013)

Table 6Top 10 States by Aerospace Job Growth 2007-2012

Boeing 787 Dreamliner assembly site in North Charleston, South Carolina. Photo courtesy of Boeing MediaRoom.

ing 21 states saw positive growth over the review period and, notably, two SLC states (North Carolina and Geor-gia) experienced triple digit growth rates. Georgia’s 122 percent increase in private sector employment in the aerospace sector (from 9,901 employees in 2002 to 22,002 employees in 2012) was all the more significant since the state also led the nation in terms of the growth in the

AEROnAuTiCs in ThE sLC sTATEs: CLEARED FOR TAKEOFF 13

One of the hallmarks of a successful state eco-nomic development strategy is ensuring that manufacturing facilities setting up operations have an adequate supply of skilled workers po-

sitioned to tackle the challenges of the complex 21st century manufacturing arena. There has been a surfeit of studies and research documenting a serious skills shortage in the contemporary American manufacturing sector, a develop-ment that could completely derail its nascent renaissance.22 These reports maintain that, unless policymakers rapidly enact aggressive policies to train and retrain a new gen-eration of manufacturing workers, America’s economic prowess in the 21st century will be crippled.

Even in the aeronautics corridor, and the broader aero-space sector, there are serious challenges related to hiring skilled labor to staff the technically demanding positions in the industry.23 As the baby boomers that populated the industry in recent decades begin to retire in substantial numbers, industry experts are noting the extreme difficul-ties associated with filling these positions with skilled new workers. Given the fact that commercial aircraft manu-facturers like Boeing and Airbus expect rising demand for

aircraft and related components in coming decades – these companies expect demand to double over the next 15 years, and the Federal Aviation Administration forecasts that the number of airline passengers will soar from 731 million in 2011 to 1.2 billion in 203224 – the role of an adequately trained workforce to meet the demand for new and rising aircraft production cannot be overstated.

In a response similar to that of the auto industry, a number of SLC states have been extremely proactive on meeting the needs of the aeronautics companies locating and expand-ing in their states.†† As previously mentioned, aeronautics officials often cite the ability of SLC states to provide an appropriately trained labor pool as an important consid-eration in their location decisions. In fact, Mr. Tim Coyle, former vice president of Boeing South Carolina, comment-ed that “[I]’ve had experience with training across many of our facilities and what we have here in South Carolina is by far the best I’ve seen.”25 Also, in South Carolina, when Eng-†† For more details on efforts in the SLC states to promote work-force development see Workforce Development in the SLC States, CanagaRetna, Sujit M., July 2013, http://www.slcatlanta.org/Publica-

tions/EconDev/workdev_web.pdf.

WORkFORCE DEvELOPMENT

Inside the Robotic Maintenance Training Center of the Alabama Robotic Technology Park. Photo courtesy of Calhoun Community College.

14 AEROnAuTiCs in ThE sLC sTATEs: CLEARED FOR TAKEOFF

land-based GKN Aerospace announced plans in November 2011 to invest $38 million and create 278 jobs over the next six years at its new Orangeburg facility, the company iden-tified the “state’s growing aerospace industry, availability of a skilled workforce and local training programs” as impor-tant in swaying its decision to open the plant.26

Details from several SLC states illustrate the manner in which these states have geared their workforce training programs to the advanced manufacturing sector, including the aeronautics industry.

AlabamaThe Alabama Industrial Development Training (AIDT) program plays a critical role in training workers for po-sitions in the new and expanding companies in the state. One of the mechanisms AIDT deploys to accomplish this goal is industry-specific training facilities such as the Ro-botic Technology Park (RTP). The RTP is Alabama’s premier training center tasked with facilitating highly advanced training in robotics and automation technol-ogies, skills critical for workers pursuing careers in the aerospace industry. The RTP comprises three individual training centers that target specific industries such as the aerospace sector.

As an example of the state’s commitment to fostering a su-perior workforce for these advanced manufacturing jobs in fields such as aeronautics, details on the Airbus project in Mobile remain salient. Specifically, of the $158 million in total incentives lined up by the state and local governments of Alabama for Airbus, $51.9 million is dedicated toward constructing a 40,000-square-foot, on-site training center where workers will be prepared, at state expense, for the complex tasks associated with the new facility.27

MissouriIn December 2013, the General Assembly convened in spe-cial session to craft a series of economic incentives to attract the production of the new Boeing 777X in the state. One of the key components of the incentive package includes pro-visions to expand the capacity of the state’s workforce in the aeronautics sector.28 Specifically, Governor Nixon an-nounced that five community colleges in the St. Louis area, i.e., the Missouri Aerospace Training Consortium, have an arrangement to train workers for advanced manufactur-ing jobs at aerospace companies such as Boeing. The five colleges include East Central College, Jefferson College, Mineral Area College, St. Charles Community College and St. Louis Community College. While all the schools cur-rently offer programs in welding, aerospace production

and assembly, and robotics and automation, the coordina-tion of efforts under the Consortium is expected to more efficiently ensure a highly proficient aviation workforce for Boeing and other companies.

South CarolinaExperts cite South Carolina’s commitment to expand workforce development in advanced manufacturing as an important reason for the state’s emergence on aero-space radars.29 In this connection, the vibrant partnership among three key players in advancing workforce develop-ment in the state – the readySCTM program, South Carolina Manufacturers Alliance (an advocacy group for the man-ufacturing sector in the state) and the South Carolina Technical College System – have proved very effective. For instance, South Carolina, just like several other SLC states, provides government-sponsored training programs so companies like Boeing can have an array of candidates for staffing their manufacturing facility. Given that many companies largely have abandoned their in-house train-ing programs, these government-sponsored programs, usually through a state initiative such as readySCTM, re-main very appealing. The program assists in recruiting and providing the initial training needs of new and ex-panding manufacturing operations in the state. To this purpose, the program effectively leverages assets across the state to provide recruitment, assessment, training de-velopment, management and implementation services to qualifying companies. In order to qualify for readySCTM assistance, “the jobs projected must be permanent; salary

Components of the Alabama Robotic Technology Park ProgramPhase I: The Robotic Maintenance Training Center houses an industry training program where technicians are trained to work on robotic machinery.

Phase II: The Advanced Technology Research and Develop-ment Center is used for the purpose of research, develop-ment, and testing of leading-edge robotics used for defense projects, space exploration, and manufacturing processes.

Phase III: The Integration, Entrepreneurial, and Paint/Dis-pense Training Center (in development) will allow compa-nies to build and adapt automation for new and existing manufacturing processes. The facility will allow companies to train in manual paint spraying techniques and robotic paint dispensing training.

Source: “Industrial Robots Training Center Prepares Alabama Workers For High-Tech Manufacturing Jobs,” Area Development Online Research Desk (2013 Auto/Aero Site Guide)

AEROnAuTiCs in ThE sLC sTATEs: CLEARED FOR TAKEOFF 15

has to be a competitive wage for the area; benefit packag-es must include health insurance; and the number of jobs created must be adequate to allow readySCTM to provide training in a cost effective manner.”30 The readySCTM pro-gram has been very effective with training workers for the Boeing manufacturing facility in South Carolina. For in-stance, Jack Jones, Boeing South Carolina’s vice president and general manager, commented in April 2012, when the first 787 Dreamliner built in South Carolina rolled out, that “85 percent of the non-management Boeing employees on site [at the South Carolina plant] were hired from within 100 miles of the plant and trained through the state’s ready-SCTM program,” a glowing testament to the type of training provided by the state.31

Another strategy pursued by South Carolina involves promoting private educational institutes such as Tri-dent Technical College’s Aeronautical Studies Division (in North Charleston, very close to the Boeing manufactur-ing facility) and Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University

to provide technical certificates in the field. In addition, several high schools in the vicinity of the Boeing facility proffer aerospace- and aeronautics-related classes to stu-dents interested in a career even before college or technical school: R.B. Stall High School (in North Charleston) hosts the Aeronautical Studies Academy and Wando High School (in Mt. Pleasant) offers an aerospace engineering course for 9th-12th grade students.32

TennesseeDuring the 2013 legislative session, Senator Mark Norris (SLC chair in 2010-2011 and CSG chair in 2014), Majority Leader of the Tennessee State Senate – along with Tennes-see House Majority Leader Gerald McCormick – sponsored and enacted SB 1330/HB1276. This bill, titled Labor Edu-

cation Alignment Program (LEAP), was designed to provide students at Tennessee’s technology centers and community colleges the opportunity to combine occupational training in a high skill or high-tech industry with academic cred-it and to apply that experience toward a degree. Senator Norris was responding to a growing challenge in a num-ber of states, including his own: the lack of a workforce adequately trained in manufacturing disciplines. Accord-ing to Senator Norris, “I’ve met with a number of industries in high-tech manufacturing ready to expand in Tennessee but for a lack of qualified employees, and I know of many Tennesseans who can’t afford to attend school while sacri-ficing a paying job. This promotes the best of both worlds for employers, employees and the economy of Tennes-see.”33 Senator Norris added, “[T]his is not unlike the old apprentice programs of generations past, where students get a practical utilization of what they’re learning from the books. But we’re adding a modern higher education com-ponent to address what Tennessee employers keep asking for: candidates with the requisite skills needed for today’s technologically advanced workplace.”34

The legislation specifically directs several state entities to work together in both establishing and carrying out the initiative. Section 4 of SB 1330 delineates several dis-ciplines, such as advanced manufacturing; electronics; information technology; infrastructure engineering; and transportation and logistics that would qualify under the LEAP legislation. As Mr. Jason Bates, administration manager at Bodine Aluminum (a company that produc-es aluminum cylinder blocks and automatic transmission parts for Toyota), in Jackson, Tennessee, stated: “[S]upport for education in manufacturing technology is critical for Tennessee’s growth”35 and Senator Norris’ successful LEAP legislation is an important step toward promoting a tech-nologically competent workforce in Tennessee.

South Carolina Manufacturers Alliance (SCMA) 2013 Legislative AgendaMSSC Certification: SCMA supports a $6.5 million state bud-get request for an initiative to create a statewide program through the technical college system for students to ob-tain the Manufacturing Skills Standard Council (MSSC) cer-tificate. The program, which is modeled after the Nation-al Association of Manufacturing (NAM)-endorsed MSSC for both production and logistics, will educate and prepare a portion of South Carolina’s workforce for entry level posi-tions in manufacturing by centering on six major themes: employability skills, academic skills, processes and produc-tion, maintenance awareness, quality and continuous im-provement, and safety.

Work Ready Community: SCMA is a partner in the Work Ready Community initiative. Developed by ACT, Inc. (the nonprofit organization focused on helping people achieve education and workplace success), a Work Ready Com-munity is a measure of the quality of a county’s workforce based on four criteria - high school graduation, soft skills development, business support, and National Career Read-iness Certificate holders.

Technical College Program Funding: SCMA supports the South Carolina Technical College System’s request for $7.54 million (non-recurring) in the state budget for the readySCTM program. The program is one of the state’s top incentives for companies looking to locate or expand and create new jobs in South Carolina.

Source: “Issues & Advocacy,” South Carolina Manufacturers Alliance

16 AEROnAuTiCs in ThE sLC sTATEs: CLEARED FOR TAKEOFF

Airbus

The July 2012 announcement by the Europe-an Aeronautic, Defence & Space Company (EADS), Airbus’ parent company, that the Euro-pean aircraft manufacturer would build its first

American factory in Mobile, Alabama, was greeted with great enthusiasm in the state and the region.36 The $600 million five-year Airbus investment will lead to a manu-facturing operation building the A-319, the very popular A-320 and the A-321, and all aircraft in the single-aisle A-320 family, by the end of 2016. These 150-seat airplanes are “the minivans of the airline world – widely-used peo-ple-haulers generally flown on short-and medium-haul trips.”37 By the end of 2017, once production reaches its peak, the facility is scheduled to build 40 to 50 aircraft an-nually. Certain aircraft components constructed at Airbus’ facilities in Toulouse, France, and Hamburg, Germany, will be transported by barge to the Port of Mobile and then trucked a short distance to the assembly line at the new fa-cility. The assembly line will be a replica of other Airbus lines in Europe, a move that reduces startup expenses. The new Airbus facility in Mobile will be built at the Brook-ley Aeroplex, a former U.S. Air Force base that was closed in 1969. Along with its 1,650-acre size, the Brookley Aero-

plex also boasts runways capable of accommodating a wide range of aircraft, another factor that was important in Air-bus’ decision in selecting Mobile.

Airbus’ motivation for establishing this manufacturing presence in Mobile was multi-dimensional:

» North America is the world’s biggest market for single-aisle planes, and Airbus forecasts that this type of aircraft will represent 26 percent of new aircraft sale volumes during the next 20 years. Given that Airbus currently maintains a market share of around 17 percent of the sin-gle-aisle market in the United States (the company splits the single-aisle market fairly evenly with Boeing on a global scale), the company is eager to expand its share of the market. Airbus officials felt that being in close proximity to its American airline customers was vital to generate new aircraft orders. In fact, it appears that this strategy already has paid off: in September 2013, Delta Air Lines announced that it has placed a “firm” order for 40 aircraft from Airbus, including 30 A-321s (with a per plane list price of $117.4 million) and 10 A330-300s (with a per plane list price of $239.4 million).38 This was Delta’s

SELECTED COMMERCIAL AIRCRAFT MANUFACTURERS OPERATINg IN THE SLC STATES

Airbus A319, featuring fuel-saving Sharklets wingtip devices. Photo courtesy of Airbus SAS 2013.

AEROnAuTiCs in ThE sLC sTATEs: CLEARED FOR TAKEOFF 17

first order with Airbus in about two decades. Airbus in-dicated that the A-321s will be constructed at its planned Mobile facility.

» The U.S. fleet of single-aisle aircraft is one of the oldest in the world, with an average age of 13 years. In contrast, the average age for single-aisle aircraft is eight years in Europe and six years in China. Experts call for some 5,000 new single-aisle aircraft in the United States during the next 20 years, and Airbus seeks to gain a much larger portion of this future market with its Mobile manufac-turing facility.

» Constructing the aircraft in Alabama helps Airbus slash its foreign exchange costs. Until the Mobile announce-ment, almost all the A-320s were built in Europe and, consequently, all costs are in euros. However, given that most aviation lending happens in U.S. dollars, these air-craft are sold in U.S. dollars. The exchange transfers raise costs for Airbus and, if even a portion of the expenses as-sociated with the aircraft is in U.S. dollars, Airbus’ overall costs shrink. Hence, the U.S. manufacturing facility cre-ates a natural currency hedge for Airbus by incurring most of its costs in dollars and not euros. (Like oil, air-craft are priced predominantly in dollars.)

» Several years before the Mobile announcement, Airbus was almost successful in landing a lucrative multibillion, multi-year mid-air tanker refueling contract with the U.S. Air Force. Eventually, Airbus lost out on this contract to Boeing. Airbus officials are convinced that having a major manufacturing presence in the United States, in Alabama in this instance, would significantly boost the company’s chances of securing future defense and military contracts with the U.S. government. In fact, analysts contend that “they want to be seen as an American company. The larg-er strategy is how this positions EADS long term. In 10 or more years, they’ll be able to go back to the Pentagon and say, ‘we have a good solid U.S. footprint.’”39

For Airbus to build its manufacturing facility in Mobile, the state is providing nearly $159 million in econom-ic incentives. This amount comprises $125 million from the state and nearly $34 million from local governments. Importantly, the total incentive package to be provided includes bond expenses, site preparation, road improve-ments, building expenses and the previously mentioned workforce training. Also included are state tax breaks on sales, use, income and property that most major, new in-dustries opening in Alabama procure. In return, Airbus agreed – when the facility is at full capacity – to create no fewer than 1,000 permanent jobs, an employment base that will generate payroll expenses of more than $61 million an-nually. The agreement that Alabama signed also includes

a clawback provision, i.e., the state will withhold funds if Airbus does not meet the employment target. Along with the direct, permanent jobs, the Airbus facility will generate hundreds of indirect and induced jobs in terms of the sup-ply chain for the facility.

In April 2013, Airbus broke ground at its $600 million Brookley Aeroplex facility and, in August 2013, officials with the Mobile Airport Authority confirmed that a bond issue totaling $260 million had been secured toward the project’s completion. The bond will be repaid by lease pay-ments from the future sales of aircraft manufactured by Airbus at the facility; while the entire proceeds of the bond issue will be allocated toward the construction of the facil-ity, the bonds were floated on Airbus’ credit and not that of the Mobile Airport Authority.

BoeingIn late 2009, in what was touted as one of the most signif-icant economic development announcements of the year, Boeing announced that it was building a manufacturing and assembly plant in North Charleston, South Carolina, the first facility the company has built outside its West Coast facilities since World War II.40 The South Caroli-na facility would build the company’s new flagship airline, the 787 Dreamliner (an aircraft with a unit cost of $193.5 million) and, at full capacity, is expected to produce 3.5 Dreamliners a month. Boeing’s initial investment amount-ed to $750 million, and the company guaranteed that the operation would generate 3,800 new, permanent jobs (over seven years) at the assembly plant, while facility construc-tion would create an additional 2,000 jobs. As is the case in many current economic incentive packages, Boeing is sub-ject to clawback provisions for the state’s up-front funds if the company does not meet its end of the arrangement; moreover, most of the tax incentives are performance-based and will not be granted unless the company actually invests the money and creates the necessary jobs.

There was some debate about the exact dimensions of the incentive package provided by South Carolina (state and local governments) to Boeing, but an extensive study car-ried out by reporters with The Post and Courier (initially in January 2010 and updated in March 2012) revealed that the total package amounted to more than $900 million, spread over 30 years. Most of the incentives took the form of property tax breaks in Charleston County (worth at least $306 million over the next 30 years) and up-front money to be given to the company through state bonds at a cost of roughly $399 million. The aforementioned $399 million involves the principal of $240 million the state is borrow-

18 AEROnAuTiCs in ThE sLC sTATEs: CLEARED FOR TAKEOFF

ing to help pay for the new facility and interest costs of $129 million. The state is spending an additional $33 mil-lion to train future Boeing workers for the facility. Boeing also is exempted from paying state sales taxes on comput-ers, jet fuel and construction materials.

At the local level, the company was granted a 10-year prop-erty tax exemption on two Dreamlifter aircraft, specially fitted 747 aircraft that Boeing uses to transport oversized aircraft parts. Given that these aircraft sell for about $250 million each, the 10-year property tax exemption was esti-mated to be worth more than $100 million. Also, Charleston County agreed on a $50 million incentive that will return half of Boeing’s already reduced property taxes on the as-sembly plant for 15 years; additionally, if Boeing invests the agreed-upon $750 million within 10 years, some of the property tax breaks could remain in force beyond 2060.

Given that the $900 million amount documented by The

Post and Courier was significantly higher than the incentive package amounts reported previously,‡‡ the South Carolina ‡‡ When the Boeing deal was announced in November 2009, the number indicated for the incentive package was $170 million. Shortly thereafter, this number changed to $450 million. Conse-quently, the more than $900 million amount reported by The Post

and Courier surprised many observers.

Department of Commerce provided details on a cost-bene-fit analysis on Boeing’s economic impact in the state. Some of these details include:

» $3.8 billion in payroll disbursements during the facility’s first 15 years of operation. This figure includes the 3,800 direct jobs along with 5,971 additional, indirect jobs.

» Importantly, a number of aviation suppliers have flocked to the state to service the Boeing facility. For instance, a range of companies such as TigHitco (a composites man-ufacturing facility in North Charleston), Carbures (an engineering and manufacturing company in compos-ites structures specializing in carbon fiber in Greenville) and Cargo Composites (a maker of air cargo containers in Charleston), all cited Boeing’s presence as the reason for locating in South Carolina.

» The total economic gain of the project over a 15-year period is estimated to be $5.2 billion.

Construction at Boeing’s 2.5-million-square-foot as-sembly facility was completed after 13 months of work (seven months ahead of schedule). Built as an extremely eco-friendly plant, the massive roof contains the largest ar-ray of solar panels in the Southeast. These panels, covering an area the size of 11 football fields, generate 20 percent of the facility’s power needs. In addition, the plant touts ef-

Boeing 787 Dreamliner enters final assembly. Photo courtesy of Boeing MediaRoom.

AEROnAuTiCs in ThE sLC sTATEs: CLEARED FOR TAKEOFF 19

ficiency in terms of waste, sending zero waste to landfills and even recycling food scraps from the dining facility.

In April 2012, Dreamliner No. 46 - with “Made in South Carolina” stenciled on its fuselage - rolled out to a raptur-ous crowd of employees and dignitaries. Not only was Dreamliner No. 46 the first Boeing-designed commer-cial jet built outside Washington’s Puget Sound region, South Carolina is the only Boeing location that carries out the entire sequence of Dreamliner manufacturing. It had taken 30 months to go from clearing dirt at the South Car-olina facility to rolling out Dreamliner No. 46, a record accomplishment.

Boeing’s success in South Carolina continued to greater heights in April 2013. The company announced an addi-tional $1-billion, 320-acre expansion that would generate 2,000 more jobs, bringing Boeing’s total employment in North Charleston to approximately 10,000. In return, the state agreed to provide Boeing with $120 million more in incentives to advance this expansion project.

In mid-December 2013, Boeing acted on the latest incen-tive package provided by the state by announcing that it would triple its footprint near Charleston Internation-al Airport.41 Specifically, Boeing closed on the purchase of 267 acres across from its 787 Dreamliner campus and also bought an additional 200 acres in the vicinity from private landowners in a $49 million transaction. The re-cently acquired land, more than previously expected, will house a new 230,000-square-foot structure to paint finished 787 Dreamliners in customers’ colors along with a new 10,000-square-foot, fully equipped fire station. The land deal and new buildings all are being purchased through the South Carolina Department of Commerce and part of the April 2013 incentive package.

Additional positive news emerging from Boeing South Carolina included reports that the site will help design and build the carbon-fiber-reinforced plastic composite inner linings of the nacelles – the pods enclosing the jet’s engines – for the forthcoming 737MAX, the successor to the cur-rent 737NG model. When Boeing and the International Association of Machinists Union in Washington initial-ly could not come to an agreement regarding developing the new 777X airplane in the Puget Sound area, Boeing received a barrage of offers to host the production of the plane from some 22 states. South Carolina (along with Alabama and Missouri) was reputedly among the front-runners to land this project. However, as indicated, Boeing workers in Washington conducted a second vote in early

January 2014 and agreed to the company’s contract terms, a development that resulted in Boeing confirming that pro-duction of the 777X would remain in the Puget Sound area.

Boeing’s impressive production forecast at all its facili-ties, not only South Carolina, is triggered by the massive demand for aircraft emanating mostly from international airlines. Through the third week of November 2013, Boe-ing had a total of 1,037 orders for aircraft with a bulk of the orders involving the 737 (780 orders), 777 (88 orders) and 787 (164 orders). In fact, at the Dubai Airshow held in mid-November 2013, Boeing secured 342 orders that netted $100 billion for the company, more than twice the value se-cured by Airbus (which received 142 orders for a net value of $40 billion). The massive commitment at the Dubai Air-show emerged from just four carriers in the tiny nations of Qatar (Qatar Airways) and United Arab Emirates (Emirates Airline, Etihad Airways and flydubai). Continuing in this vein, in late December 2013, Boeing announced that it had secured its first order from Asia for the forthcoming 777X jet, an order valued at $7.5 billion, from Hong-Kong-based Cathay Pacific Airways.42 Cathay, Asia’s top international carrier, will acquire 21 of the larger 9X version of the plane between 2021 and 2024 and deploy them on routes to North America and Europe. Not only will the 777X be Boeing’s first passenger aircraft of the next decade, the order will be critical to staving off competition in the long-haul market by arch competitor Airbus.

Aviation analysts expect that Boeing’s association with South Carolina will continue to solidify in the coming years, estimating that “[T]he long-range plan at Boeing is to shift all 787 production to Charleston.”43 Analysts an-ticipate that production at the South Carolina facility, including future versions of the Dreamliner 787, the 787-10, one day will rival Boeing’s massive operation in Everett, Washington.

While progress at the Boeing South Carolina facility has been mostly positive, the operation has not been without controversy for two reasons:

» The National Labor Relations Board, questioning the le-gal standing of the site’s new final assembly line, charged Boeing with selecting South Carolina over Washington in retaliation against past strikes by the International As-sociation of Machinists Union. This legal issue dissipated in 2012 when the Union agreed to drop its objections to the Dreamliner’s production in South Carolina after clinching a deal with Boeing to produce the new 737 air-craft in Renton, Washington.

20 AEROnAuTiCs in ThE sLC sTATEs: CLEARED FOR TAKEOFF

» The Dreamliner, owned and operated by several airlines (including Nippon Airways, Norwegian Air and Poland’s LOT) has been plagued by a series of technical glitches in the past year that resulted in the Federal Aviation Ad-ministration (FAA) grounding all Dreamliners for four months. While these technical glitches have not been catastrophic, they were sufficiently alarming to force the FAA and Boeing (along with a number of other federal and private entities) to carry out extensive research to first determine and then eliminate these technical snafus.

gulfstreamIn 1967, Grumman Aircraft Engineering, a company locat-ed in Bethpage, New York, decided to relocate to Savannah, Georgia, with a mere 100 employees.44 The company, which had been known for developing military aircraft, had just branched out into developing jet powered aircraft for corpo-rate executives. Grumman, which was renamed Gulfstream a few years later, enjoyed sustained success in the following decades and, by 2011, had industriously launched the G650, the flagship aircraft of the company. The G650, with a price tag upwards of $60 million, can fly 18 people at nearly nine-tenths the speed of sound, nonstop between Shanghai and New York. Gulfstream also manufactures the G550, G450, G280 and G150. Powered by more than two decades of re-search, Gulfstream also is working toward developing a supersonic business jet, the Gulfstream Whisperer.

Since its arrival in Georgia in the late 1960s, public offi-cials increasingly have recognized Gulfstream as one of the most noteworthy corporate entities in the Savannah area and in the state. All of the company’s research and devel-opment occurs in Georgia (mainly Savannah, but also in Brunswick), with additional operations in California, Flor-