‘Blue boats’ and ‘reef robbers’: a new maritime security ... · §WorldFish, Penang,...

Transcript of ‘Blue boats’ and ‘reef robbers’: a new maritime security ... · §WorldFish, Penang,...

‘Blue boats’ and ‘reef robbers’: A new maritimesecurity threat for the Asia Pacific?

Andrew M. Song,*,† Viet Thang Hoang,‡ Philippa J. Cohen,*,§ Transform Aqorau¶,∥,**

and Tiffany H. Morrison**ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, James Cook University, Townsville, Australia.

Email: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected].†WorldFish, Honiara, Solomon Islands.

Email: [email protected], [email protected].‡School of Political Science and International Studies, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia.

Email: [email protected].§WorldFish, Penang, Malaysia.Email: [email protected].

¶iTUNA Intel and Pacific Catalyst, Honiara, Solomon Islands.Email: [email protected].

∥School of Government, Development and International Affairs, University of the South Pacific, Suva, Fiji.Email: [email protected].

**Australian National Centre for Ocean Resources and Security, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, Australia.Email: [email protected].

Abstract: Vietnamese ‘blue boats’ – small wooden-hulled fishing boats – are now entering the territorial watersof Pacific Island countries and illegally catching high-value species found on remote coastal reefs. Crossing severalinternational boundaries and traversing a distance of over 5000 km, these intrusions have alarmed Oceanic coun-tries, including Australia. Lacking administrative capacity as well as jurisdictional authority to effectively control thevast stretches of island coastlines individually, governments and intergovernmental bodies in the region have calledfor strengthened coordination of surveillance efforts while also pressuring Vietnam diplomatically. This paperreviews these latest developments and is the first to provide a focused assessment of the issue. Through the lens ofCopenhagen School of securitisation theory, we analyse responses of national and regional actors and their por-trayal in online media to understand how blue boats are constructed as a security threat within a narrative of mari-time, food and human security. Arguably, Australia together with the Forum Fisheries Agency, who advise on thegovernance of offshore tuna resources, have so far acted most decisively – in a way that might see them extendtheir strategic role in the region. We propose a comprehensive empirical research agenda to better understand andmanage this nascent, flammable and largely unpredictable inter-regional phenomenon.

Introduction

For the people of the Pacific Islands, fisheryresources found in reefs, lagoons and coastalsea areas are a crucial part of their sustenance,contributing to their food and livelihood secu-rity as well as being a central element in thePacific way of life (Johannes, 1978; Gillettet al., 2000). Spanning over a 6000 nauticalmile stretch of the western and central PacificOcean, the remoteness of these islands, togetherwith the small land mass and the predominantlycoastal-residing populations further accentuatethe central roles of fish and the ocean. In recent

years, several sightings of poaching fleets fromoutside the region have alarmed coastal com-munities, national governments and inter-governmental organisations. Referred to as ‘blueboats’ (or ‘reef robbers’), a flotilla of small-to-medium-sized fishing boats from Vietnam hasmade what must be a long, arduous journey totarget coastal reefs in Palau, Papua NewGuinea, Solomon Islands and other Pacificcountries and territories to collect high-valuespecies of sea cucumber and giant clam. Poten-tial impacts of this foreign fishing intrusion areforecast to be acute and multidimensional,eliciting widespread attention and a call for

Asia Pacific Viewpoint Vol. 60, No. 3, 2019ISSN 1360-7456, pp310–324

© 2019 The Authors. Asia Pacific Viewpoint published by Victoria University of Wellingtonand John Wiley & Sons Australia, LtdThis is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License, which permits use anddistribution in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, the use is non-commercial and no modifications or adaptations are made.

doi:10.1111/apv.12240

urgent action by the mainstream media as well asin the speeches of national and regional actors. Atthe local level, poaching of sea cucumber woulddirectly deplete the inshore resources and deprivethe communities of an export-based, income-generating opportunity. Such illegal, unreportedand unregulated (IUU) fishing is also an affront tothe efforts communities and national governmentshave made towards the management and recov-ery of these resources, many of which are nowunder national bans and/or international protec-tion (Anderson et al., 2011). In addition, theoccurrence of blue boats glaringly exposes the dif-ficulty of national governments to monitor andpatrol the vast stretches of coastal waters in thePacific (e.g., Aqorau, 2000; McNulty, 2013).Pacific countries, many of whom qualify as smallisland developing states, are typically equippedwith scarce surveillance capacity (Govan, 2014).Beyond detection, the apprehension and the sub-sequent legal-administrative treatment of theseboats and the crew can also take several monthsand be a resource-intensive operation for PacificIsland countries (PICs).Up until now, this emerging Asia Pacific issue

has been mostly reflected in increasing mediaattention. While analysis of occurrences andhandling of blue boats have been presented in arather bite-sized manner, their media portrayalhas nonetheless resulted in effective issue-mak-ing. This is typical of a nascent and data-poorphenomenon; however, there is now a need fora more reflexive and coherent interpretationgiven the varied repercussions the issue couldbring to the region. Such interpretation would‘turn circumstances into a situation that is com-prehensible and that serves as a springboard toaction’ that is, ‘sense-making’ (sensu Taylor andVan Every, 2000: 40; Weick et al., 2005). Wetake a discursive point of view to delineate anarrative about the nature of the threat theincursions of blue boats pose and the meaningsthey generate, in order to inform regional iden-tity and action. Approaching blue boat incur-sions as a maritime security issue, this paperdraws on the constructivist analytical frame-work of the Copenhagen School of sec-uritisation theory (Wæver, 1995; Buzan et al.,1998) and evaluates how the acts of fishingincursion and the responses of various Pacificactors have been packaged from the perspectiveof online media, what purposes these measures

serve, and what (geo)political trends these devel-opments hold for the future. Overall, we arguethat this issue is en route to being securitisedsuch that urgency is raised and emergency mea-sures are legitimised to bolster multilateral coop-eration on maritime monitoring and surveillance.In doing so, we also highlight the political natureof this process, whereby potential for assertingone’s influence or sovereignty is gained or lostamong various Pacific actors.This study relied on publicly accessible sec-

ondary sources from 2015 to 2018 and informaldiscussions with key informants to conduct acritical textual analysis (Vaara and Tienari,2002; Fairclough, 2013). English language arti-cles that emanated from the various media out-lets of PICs as well as Australia and New Zealandrepresented material used to assemble region-relevant perspectives. Articles were searched peri-odically between December 2017 and October2018 using an online search engine with a com-bination of keywords, including but not limited to‘blue boats’, ‘Vietnamese’, ‘Pacific Islands’,‘poaching’, ‘sea cucumber’ and ‘illegal fishing’.All results were initially retained and reviewed.Because the coverage of the same event is oftenreproduced by more than one media outlet, anyrepetitive reports were omitted from the final setof articles. We also examined Vietnamese lan-guage articles to gain a preliminary understandingof how the issue is framed and dealt with at the‘source’ location. Eighty-two articles were col-lected in total (55 in English; 27 in Vietnamese) inorder to reach saturation (see Table S1,Supporting Information, referenced at the end ofthis paper, for a complete list). From this, we iden-tified key actors and events while extracting state-ments and quotes particularly useful forrepresentational purposes, as they are also in linewith the sentiments found throughout the reportedmaterial more generally. Informal discussions withthose in various professional circles encompassedboth open-ended chance conversations and pre-scheduled chats but with no strict data collectionagenda. The broad understanding gleaned fromthese discussions helped contextualise the analy-sis of the media articles. This work also benefitsfrom our diverse and extensive research experi-ences on coastal, offshore and transboundary fish-eries in the Asia-Pacific, including Vietnam andPICs. We are open-minded about the blue boatincidents and have no conflict of interest.

© 2019 The Authors. Asia Pacific Viewpoint published by Victoria University of Wellingtonand John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd

311

Securitisation of blue boats in Asia-Pacific

The paper proceeds with a brief synopsis ofthe evolving concept of maritime security. Next,the history and the traditional content of mari-time security concerns and actions in the Pacificare presented. Against this broad context, wethen situate the blue boat incursion and thethreats it would pose to the region. The subse-quent section describes the occurrences of theblue boats and the regional and national reac-tions taken and claimed so far. We then explainthis development through applying thesecuritisation framework of Barry Buzan, OleWæver, and colleagues. Finally, we highlightthe implications of the securitisation narrativesurrounding this phenomenon and situate themwithin the broader understanding of maritimesecurity. The paper concludes by proposing afuture research agenda, which can help betterprepare Pacific actors for the likely prospect ofcontinued threat construction on blue boats.

Maritime security in the Pacific Island region

While it is difficult to achieve a consensus overdefinition, maritime security is increasinglyimportant to international relations and oceangovernance. According to Bueger (2015: 159),the growing incidence of piracy in the pastdecade together with the build-up of blue waternavies of emerging powers such as India andChina and inter-state hostilities in regions suchas the South China Sea have moved maritimesecurity to the global consciousness and tohigh-level policy agendas (see also Ross, 2009).Traditionally, maritime security has been associ-ated with military threats and sovereignty viola-tions of sea-based territory. A greater range ofdefence and safety-related goals are now part ofits lexicon including the protection of the free-dom of navigation and the flow of internationaltrade as well as averting dangers of terrorism,drug trafficking, piracy, people smuggling andother forms of transnational crime (Klein et al.,2010: 5). Further, threats to a state’s security areclosely linked to environmental, economic andsocial conditions. For example, in the 2008Report on Oceans and the Law of the Sea, theSecretary-General of the United Nationsidentified seven specific threats to maritimesecurity, which included IUU fishing (https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/

N08/266/26/PDF/N0826626.pdf). Recognisingfood insecurity as a major risk to internationalpeace, of which fisheries form a vital supplyin many parts of the world (Cohen and Pinstrup-Andersen, 1999; Pomeroy et al., 2007), this par-ticular threat also invites human security con-cerns affecting the vulnerability and resilienceof coastal populations as well as the welfare ofseafaring fish workers (Adger, 2010; Bueger,2015; Macfarlane, 2017). Likewise, intentionaland unlawful damage to the marine environ-ment and climate change uncertainty are alsokey parts of the maritime security discussion, fortheir potential to destabilise social and eco-nomic interests of coastal states through, forinstance, creating environmental refugees orderailing the pursuit of the ‘blue economy’,which requires secure and well-managed marineenvironments as a precondition to ocean-basedsustainable development (Klein et al., 2010;Duarte, 2016; Barnett, 2017; Voyer et al., 2018).

For the 22 PICs and Territories that comprisethe Pacific Island region in the Western andCentral Pacific, the ocean remains a source oflife and prosperity that has sustained Pacificpeoples for generations. Maritime issues forthese countries frequently focus on the health ofthe marine environment including coastalresources that provide food and tourism earn-ings, the sustainability of offshore fishing stocksfor national income generated from licencefees, marine pollution from shipping and land-based activities, the introduction of marineinvasive species, and the social and ecologicalimpact of climate-change-induced sea-level riseand destructive weather events. Hence, con-cerns about maritime security have mainlyreflected these environmental and resource-related matters rather than the naval, defence-oriented concerns more prominently discussedin larger, more developed states (Firth, 2003;Bateman and Mossop, 2010). Similarly, analystshave noted that the PICs do not necessarily pri-oritise the risk of maritime terrorism and piracy(Fletcher, 2004; Fortune, 2006; Jones, 2009).This has meant that counter-terrorism measureshave been at times exaggerated or even imposedby others at the expense of greater attention tothe issues the PICs themselves deem more urgent(e.g. PICs having to respond to the UN SecurityCouncil resolutions that address terrorism andstrengthened container and port security

312 © 2019 The Authors. Asia Pacific Viewpoint published by Victoria University of Wellingtonand John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd

A.M. Song et al.

measures). In this regard, Bateman and Mossop(2010: 101) observed that, ‘increased port securityhas had a social cost, as local people are nowdenied fishing or other recreational access towharves and jetties used by international shipping.’As part of the traditional ocean-going activity,

fishery and fishing vessels provide a saliententry point to maritime security discussions inthe Pacific Island region (Martin, 2005;UNODC [UN Office on Drugs and Crime],2016). In addition to being a main conduit forillegal fishing, the possibility that fishing vesselscould be involved in the trafficking of weaponsand drugs and people smuggling has been longnoted. While the security of air access pointshas seen significant improvements over theyears (Bateman and Mossop, 2010), control ofseaborne activity is understandably challengingdue to the geographical expanse of the region(spanning over a marine area of 30 millionsquare kilometres). This challenge is exacer-bated by difficulties of inter-country and agencycoordination, which is needed to compensatefor the limited domestic capacity (e.g. shortageof patrol vessels, surveillance aircraft and oper-ating costs relative to the size of national mari-time jurisdictions). Nevertheless, significantcollective efforts have been mustered to addressIUU fishing in the region. Since 1999, theForum Fisheries Agency (FFA) has played a keyrole in managing and supporting member coun-tries in the implementation of a satellite-basedVessel Monitoring System (VMS) to track themovement of large-scale tuna-catching vessels intheir exclusive economic zones (EEZ). FFA alsoadministers and provides support for multilateraltreaties that aim to set up a cooperative frameworkfor region-wide surveillance. For instance, the1992 Niue Treaty on Cooperation in Fisheries Sur-veillance and Law Enforcement in the SouthPacific Region (and the 2012-finalised Agreementon Strengthening Implementation of the NiueTreaty, i.e. the Niue Treaty Subsidiary Agreement),contains provisions on the sharing of resourcesand data as well as procedures for flexible cooper-ation in monitoring, prosecuting and penalisingillegal fishing vessels. Having the potential toextend its scope to cover a broader range of suspi-cious activities beyond fisheries, the Treaty alsohas the means to facilitate improved coordinationof air surveillance, regarded by some commenta-tors as the most pressing operational requirement

for regional maritime enforcement (see Aqorau,2000; Bateman and Mossop, 2010).The implementation of the Niue Treaty, how-

ever, has been slow and intermittent at best,marred by complex factors such as a sensitivityto national sovereignty, particularly when for-eign (or regionally managed) vessels areallowed to conduct enforcement operations innational areas of jurisdiction (Bateman andMossop, 2010; see also Radio New Zealand,2017a). PICs have only gained independencefrom Western colonial powers in the secondhalf of the 20th century, and some only asrecently as the 1990s (e.g. Palau). Hence, will-ingness to cooperate closely with other actorscan be affected by ‘a perception that the state isgiving up something seen as a sovereign right,or natural sphere of influence’ (Bateman andMossop, 2010: 111). Concerns about sover-eignty have also influenced the relationship ofPICs with Australia and New Zealand – the twolarger, more advanced ‘metropolitan’ states inthe region (e.g. see Murray and Overton, 2011).Australia and New Zealand, in part driven bytheir own national interests to secure a ‘peace-ful’ Pacific (i.e. free of resource depletion, trans-national crime and terrorism risks) haveidentified a need for improved maritime securityand devoted significant resources to increasethe infrastructural and bureaucratic capacities(e.g. patrol boats and training of governmentofficials) of the PICs to respond to ocean-basedthreats (Rolfe, 2003; Fortune, 2006; Hayward-Jones, 2015). However, the sense that metropol-itan countries are at times ‘seeking to imposetheir will and to establish arrangements that suitthem rather than the PICs’ has not goneunnoticed in the region (Bateman and Mossop,2010: 111), with Fortune (2006: 59) also statingthat ‘most PICs are uncomfortable addressingwhat New Zealand and Australia regard as themost serious security challenges’. This antago-nistic dynamic that exposes differences of prior-ities has been similarly observed in the westernIndian Ocean, where national Somalian actorshave tended to attach more importance to theaspects of blue growth and human securitywhile external donors have stressed anti-piracyor counter-terrorism activities (Bueger andEdmunds, 2016).Such challenges are reflective of the general

problem of coordination and cooperation that

© 2019 The Authors. Asia Pacific Viewpoint published by Victoria University of Wellingtonand John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd

313

Securitisation of blue boats in Asia-Pacific

needs to be addressed in order to institute an effec-tive maritime security regime (Bueger, 2013). Inthe following section, we explore how blue boatsare providing additional impetus for strengtheningregional security and interdependence. Morespecifically, we analyse the ways in which thenascent phenomenon of the blue boat incursionis subject to processes of ‘securitisation’, enrolledto promote added urgency to bolster the securityrationale.

Blue boats in the Pacific

Blue boats and their operation

Blue boats are a label given to fishing boatsfrom Vietnam that have been spotted poachinghigh-value sedentary species in the remotecoastal reefs of the Pacific Islands. Blue simplybecause of the painted colour of the hull whichis in fact very typical of fishing boats in Viet-nam, these are relatively small boats of10–15 m in length, which can carry 10–17 crewonboard. First making headlines in 2015, theblue boats have now been sighted (andapprehended) in the waters of many PICsincluding Palau, the Federated States of Micro-nesia (FSM), Papua New Guinea, SolomonIslands, Vanuatu and New Caledonia as well asAustralia. They travel more than 7000 km andstay up to three months at sea, allegedlyenabled to stay those durations by thesuspected logistical arrangement of tranship-ment carriers arriving to receive the caught fishand provide fuel in the course of their trip(Blaha, 2016). Between December 2014 andSeptember 2016, the FSM seized more thannine Vietnamese vessels and arrested approxi-mately 169 crew members (Carreon, 2017a). InAustralian waters, according to the AustralianFisheries Management Authority, the number offoreign fishing boats caught operating illegallyis reported to have increased from six in 2014to up to 20 in 2016 with most originating fromVietnam and Indonesia (Field, 2017).Sea cucumber appears to be the main target

of blue boats. Two blue boats intercepted in thewaters of New Caledonia in November 2017were found to be carrying on board 10 tons ofgutted and salted sea cucumber in 58 barrels(Carreon, 2017b). As sea cucmber is a culturally

important delicacy in many parts of East andSoutheast Asia including Hong Kong and main-land China, its harvest and export to these Asianmarkets are integrated into an efficiently oper-ated market chain (Purcell, 2014; Barclay et al.,2016; Fabinyi et al., 2017). Concurrently, nota-ble patterns of over-exploitation similar toboom-and-bust cycles followed by harvest orexport bans in countries such as Papua NewGuinea, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu havebeen evident (Anderson et al., 2011; Hair et al.,2016). Tropical sea cucumber species can retail(as a dried or processed product called bêche-de-mer) at AU$150–300 per kg in Hong Kongand Chinese markets (Purcell et al., 2018) pro-viding a considerable financial incentive forblue boats operators whose wooden-hulledboats represent a relatively small investment(reportedly costing around AU$15 000–35 000each) (Blaha, 2016). Furthermore, consumerdemand in China is expected to rise in line withthe growing middle class (Fabinyi et al., 2017).

The growing encroachment of blue boats intothe Pacific may also be driven by depletion offish stocks in waters nearer to Vietnam in theSouth China Sea (Pomeroy et al., 2009). In addi-tion, fishing in these traditional fishing groundshas been made more problematic by Chinesepolitical and para-military interferences (Dupontand Baker, 2014; Zhang and Bateman, 2017).Since the late 1990s, the Vietnamese Govern-ment has implemented strategies that encourageoutward expansion of its fishery by limitingnearshore fishing and subsidising constructionof bigger vessels capable of venturing to off-shore waters (Pomeroy et al., 2009). Insearching for new areas to operate, the intrusionblue boats intrude into the waters of to thePacific Islands and Australia; this is part of thewider trend that sees them also in the waters ofneighbouring countries, such as the Philippines,Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand. Blue boatspurportedly travel through unpatrolled marineroutes whenever possible, and look foruninhabited islands to scour the surroundingarea for sea cucumber; the boats then move fur-ther towards inhabited islands in search of more(Phòng, 2017, translated). Collection of seacucumber in foreign waters is apparently easierand less dangerous in operational terms, too,since sea cucumber is still found 6–7 m deep,whereas one must dive 60 m, and even 80 m in

314 © 2019 The Authors. Asia Pacific Viewpoint published by Victoria University of Wellingtonand John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd

A.M. Song et al.

waters near Vietnam in the South China Sea(Voice of America, 2017a, translated). Mr PhanHuy Hoàng, President of Fisheries Associationsof Quang Ngai Province, from which thehighest incidence of blue boats originate, hasportrayed the operation thus: ‘with a smallwooden fleet, fishers turn off communicationequipment and turn off the lights as well. Theykeep moving quietly. No one monitors, nomeans can detect them … People are willing tobe hung to get the 300-time higher profits, justlike drug trafficking’ (in Hoàng, 2017, trans-lated). Participating in such a journey is a pre-carious undertaking with potentially direconsequences. Crews reportedly have no con-tract of employment and no insurance; andwhen there is a problem such as occupationalaccidents or arrests, the owner assumes noresponsibility and even cuts off all ties with thefishers (Voice of America, 2017b, translated). Itis also possible that some of the crew are vic-tims of human trafficking conducted by theowners of the blue boats, although such claimsremain unsubstantiated at time of writing(Buchanan, 2017).

Impacts and responses

Poaching of coastal marine resources, such assea cucumber, can directly endanger the liveli-hood security of coastal communities and a sig-nificant source of national export revenue in thePacific (Gillett, 2009). Sea cucumber fisheriesare estimated to be the second-most valuableexport fishery for the PICs after tuna, and morelive tonnage in sea cucumbers is extracted andtraded annually than all other reef fisheriescombined (Carleton et al., 2013; Gillett andTauati, 2018). Sea cucumber are often a pri-mary source of income for the fishers who par-ticipate in the fishery; for instance, sale of freshand dried white teatfish (Holothuria fuscogilva),respectively, can fetch an average fisher-to-buyer price of AU$31 per piece and AU$61 perkg in Fiji (2014 data) and AU$9 per piece andAU$39 per kg in Kiribati (2011 data) (Purcellet al., 2016). Other livelihood options availablein rural areas may be relatively more stable(e.g. production of copra), but are a far lesslucrative source of income. Hence, when seacucumber stocks collapse or the fishery closes(in many instances, swiftly and without much

warning), this sudden loss of livelihood can leadto a considerable hardship for many islandinhabitants (Koczberski et al., 2006;Christensen, 2011).As well as jeopardising resource management

and income generation efforts, controlling theincidence of blue boats has also inflicted largefinancial and administrative burdens on PICs.The essential procedures for achieving border-,human- and biosecurity would entail activitiespertaining to monitoring, capturing and the san-itary disposing of the boats as well as fair andhumane prosecution, detainment and repatria-tion of the crew. For instance, Suzanne Lowe-Gallen, Chief of Compliance and Technical Pro-jects for the FSM, stated that surveillance andarrests of nine blue boats that had been illegallyfishing in FSM waters during the past three yearshad cost the government over AU$250000(in PNA, 2016a). Similarly, French authoritiesestimated US$1.5 million (~AU$2.1 million) asthe total cost of handling the November 2017infraction in New Caledonia, with New Cal-edonia’s representative to the Western and Cen-tral Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC)Manuel Ducrocq being quoted as saying:

‘For 12 crew members, we are obliged by theFrench law to see that they are accompanied by15 police officers … So not only do we have thecost of surveillance, the interdiction and thentheir accommodation but in addition we mustpay 15 return airline tickets for our police toensure these people arrive in Vietnam. That is ahuge cost which is borne by the government andcannot be recovered’ (in Rika, 2017).

The growing risk of blue boats has been metin the region with strong rhetoric and swiftaction. Vietnam is being diplomatically pres-sured by the PICs to ‘to do more to prevent thisillegal activity’ (see PNA, 2016b). This issue hasbeen raised at the annual WCPFC meetings(in both 2016 and again in 2017) where theVietnamese delegate was directly confrontedand asked to provide a response. The FFA hasalso requested an update on the implementationof the Vietnamese Prime Minister’s officialdirective issued in May 2017, which specified arange of (Vietnamese) domestic actions to con-trol the behaviour of its fishing vessels (seeWCPFC, 2018). The WCPFC Executive Director,

© 2019 The Authors. Asia Pacific Viewpoint published by Victoria University of Wellingtonand John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd

315

Securitisation of blue boats in Asia-Pacific

Feleti Teo, confirmed the adversarial sentimentamong the PICs, ‘in the context of the [WCPF]Commission there has been attempt to link (blueboats to membership) because, as you know,most of the blue boats originate from Vietnamand Vietnam is a cooperating non-member’(in Carreon, 2017c), implying that the continuedpoaching by blue boats could have an effect onthe success of Vietnam’s application to be amember of WCPFC.Countries within the Pacific region appear

keen to apply a coordinated approach to thesurveillance and apprehension of blue boats.Operation Rai Balang is an annual 10-day mari-time surveillance sweep led by the FFA’sRegional Fisheries Surveillance Centre andjoined by nine Micronesian and Melanesianstates as well as the aerial and maritime defenceassets of the ‘QUADS’ (Australia, New Zealand,France and the US); it conducts unannouncedpatrols in the EEZs of the PICs and the high seas(i.e. areas beyond national jurisdiction) to detectand seize IUU fishing vessels. Expanding fromthe primary target of large-scale distant-waterfleets such as purse seiners or long-liners, the2017 operation was the first of any FFA surveil-lance operation to support a secondary missionof searching for, and reporting, blue boats viaair surveillance sorties in the 14.7 million km2

wide patrol area (FFA, 2017a). Three blue boatswere pursued out of the Papua New GuineaEEZ, which supplemented the results of the2016 exercise, in which the detection and arrestof three blue boats was achieved within thewaters of Palau and FSM (FFA, 2016).The capture of three blue boats in March

2017 near Indispensable Reef, 50 km south ofRennell Island in Solomon Islands, provides anexample of a coordinated, multi-agencyapproach to conducting surveillance and detec-tion, and ultimately arrest. After receiving areport of blue boat sighting from a registeredcommercial fishing vessel operating in the area,the FFA, which is headquartered in Honiara,alerted the Royal Solomon Islands PoliceForce, who dispatched a patrol boat the follow-ing day. The French Government also providedaerial support upon request of the FFA bydeploying an aircraft from New Caledonia toSolomon Islands on an emergency basis. Withan updated report from the police and fisheriesauthorities based in Santa Ana Island, the

French aircraft was able to locate the boats,which enabled the patrol vessel to overtake andboard the blue boats. This case has beenheralded regionally as a successful illustrationof multiparty cooperation among local, nationaland international actors, as it led to pinpointingand ultimately apprehending the blue boats andtheir crew (Movick, 2017). Since then, FFA con-vened a special meeting in Brisbane in May2017 attended by the senior officials of the PICsto collectively develop a strategic response toaddress the broad consequences of border andresource violations from blue boats as well as toplan a concerted diplomatic action directedtowards the Vietnamese Government (FFA,2017b). Two key outcomes explored were the‘draft Blue Boat Strategy’ and the expansion ofFFA’s mandate to include coastal inshore areas(Tauafiafi, 2017a). Regarding the latter, with aregion-wide surveillance system already inplace for offshore oceanic fishery resources, thisconsolidation of mandate within FFA isexpected to enable a more effective coordinationof blue boat surveillance – a significant proposi-tion we further elaborate in the subsequentsection as part of the nascent securitisationnarrative.

Securitisation of blue boats

Offering a concept of security that is broad andgeneric enough to encompass different sectorsof security (military, economic, societal andenvironmental) at the individual-, state- andinternational-level, Barry Buzan and OleWæver have argued that there is a genuinelogic to how an issue becomes understood as asecurity threat. Constructionist in its epistemol-ogy, their ‘securitisation framework’ enables ananalysis of the political process by which threatsare constructed and issues are elevated on thesecurity agenda (Bueger, 2015: 161). Accordingto this Copenhagen School of thought,securitisation implies that a particular issue issuccessfully claimed as an existential threat(e.g. a matter of survival) to a certain referentobject (e.g. state sovereignty or community live-lihoods). Such claims (i.e. ‘speech acts’) aremade by ‘securitising actors’, who typically rep-resent political elites empowered or authorisedto speak about security (e.g. governments,

316 © 2019 The Authors. Asia Pacific Viewpoint published by Victoria University of Wellingtonand John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd

A.M. Song et al.

bureaucracies, lobbyists and pressure groups).In turn, if accepted by a relevant target audi-ence (e.g. international community), theseclaims as a ‘securitising move’ will lead tolegitimising special or ‘emergency’ measuresthat would not have otherwise been possiblehad the discourse not taken the form of existen-tial threats. Hence, securitisation is about thediscursive process that justifies taking actionsoutside the normal bounds of politics in orderto avert what is perceived as a threateningdevelopment (Buzan et al., 1998).In the case of blue boats, alarmist language

has already been used to depict the boats them-selves, the impact of their activities and thebroader dangers they pose. The Director Gen-eral of FFA, James Movick, preferred to callthem ‘reef robbers’ (Movick, 2017). Blue boatshave also been compared to a ‘thief in thenight’, who enters the home and steals the mostprecious possessions (Carreon, 2017a). AnotherFFA official remarked, ‘When they go to a reef,they don’t catch a few [sea cucumbers], theycatch them all. Sea cucumbers need a certainamount of number to reproduce. Blue boats willobliterate them from the reefs. They [sea cucum-bers] will never grow there again’ (in Tauafiafi,2017a). In this discourse, the imperative to con-trol the incursions of blue boats is thus conspicu-ously linked to the referent objects- that is, thestatus of the marine resources as finite and underthreat- and then the survival of the coastal com-munities who depend on those marine resourcesfor their livelihood and food security (seeCullwick, 2016; Tauafiafi, 2017b).Forming part of the speech act, blue boats are

also spoken about in the same breath as mari-time border security and associated trans-boundary crimes such as drug trafficking. PapuaNew Guinea Fisheries Minister Mao Zemingstated, ‘It is not just an illegal fishing matter tobe addressed by the [PNG] National FisheriesAuthority. It is a national security issue whichmust be raised at the highest diplomatic levels’(in Albaniel, 2016). Similarly, ViliameWilikilangi, a regional security advisor to thePacific Islands Forum Secretariat, confirmed thedisruptive role of blue boats in preserving terri-torial control of member countries:

‘Our focus on maritime security, which is some-thing we’ve identified across a number of

countries in the region, is around the issue ofborder security and being able to have enoughmaritime domain awareness regarding the move-ment of small craft vessels, fishing vessels in andout of our various economic exclusion zones …[For example], Vanuatu has had issues in thepast with yachts coming in with drugs and youknow it is along some of the transshipmentroutes from the US to Australia and also toNew Zealand. So, these are concerns we arereally trying to look at and have these reflectedin the policy’ (in Cullwick, 2018).

As such, the sovereign control of maritimedomain has effectively been elevated as anotherreferent object.In the current shaping of the blue boat dis-

course, FFA appears to be one of the most vocalsecuritising actors, if not the most dominant.FFA’s core mandate is to assist member coun-tries to sustainably manage offshore fisheryresources such as tuna and other pelagic fishstocks located in their EEZs. FFA’s operations,therefore, do not extend into coastal waterswhere the risk of blue boats appears to con-verge the greatest. Then, why is FFA visiblyactive in intervening in the operations of blueboats? James Movick of FFA explained in amedia interview,

‘We do have a very effective tool in place [refer-ring to the Regional Fisheries Surveillance Cen-tre] and we do need to use it, as these areproblems affecting the sovereignty of our coun-tries, the livelihoods and opportunities that existfor our own people to harvest these resources …So we have the responsibility but also the oppor-tunity of using the regional MCS [monitoring,control and surveillance] framework’(in Tauafiafi, 2017b).

Probing further, in representing FFA’s position,Movick was clear on the new direction requiredto ward off blue boat intrusion that centres onaerial surveillance. He was quoted as saying,

‘They [blue boats] are a particular concernbecause they are small wooden vessels that arenot easily detected by our day-to-day activitiesand the traditional [radar] tools that we havebuilt around the industrialised tuna fishery …

Moving forward, this new form of threat willrequire us to evolve tools and practices craftedto local conditions. Aerial surveillance will

© 2019 The Authors. Asia Pacific Viewpoint published by Victoria University of Wellingtonand John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd

317

Securitisation of blue boats in Asia-Pacific

become more vital and be utilized more broadlythan for just enforcing tuna fisheries alone’(FFA, 2016).

FFA’s deputy Director General at the time, WezNorris, also elaborated on the broader vision ofthis strategy,

‘It [aerial surveillance] means we will be able todeploy it around the region in support of whenour members have their patrol boat out at seaand that is when we get the best value out ofcombining that capability … The increasedaerial assistance capacity will broaden our scopeand the impact that we have on a whole rangeof issues from the detection of sort of non-tunaillegal fishing like the blue boats that we haveseen from Vietnam, but also allowing us to overtime and as the members get more comfortableto move into looking at broader trans-nationalcrime risks that are not necessarily fisheries spe-cific … This is where the future I see us havingto move. To understand that there are other bor-der control issues where our regional [MCS]framework can play a role’ (in Tauafiafi, 2017c).

Encouraged by the effective response demon-strated in the capture of blue boats in SolomonIslands in 2017, the intent of the FFA is report-edly to seek a full mandate from the membercountries to expand its operation to coastalwaters (see Tauafiafi, 2017a,2017b). Such anextension, if approved, would enable theagency to monitor the territorial waters of PICswith greater frequency and intensity and evendeploy foreign aircrafts into the country on anemergency basis. While this would be a highlysensitive proposal from a sovereignty perspec-tive, if not an outright aberration, it likely buildson a precedence called the 2000 BiketawaDeclaration in the Pacific, which sets out aregional framework that allows a collectiveintervention into domestic affairs in times ofpolitical or security crisis and gives the extrapower to the Pacific Island Forum (the preemi-nent inter-governmental body made up of headsof state) in determining when and how thattakes place (Frazer and Bryant-Tokalau, 2006).FFA’s aspiration is in some ways also tied to a

securitising move of Australia, who as a metro-politan partner and the largest donor of foreignaid to the Pacific region launched a plan toboost the aerial surveillance capacity of FFA in

2017. This support, for the first time, added a(civilian) patrol aircraft under the direct opera-tional control of the FFA, who will have year-round access to the feature with FFA membersdetermining surveillance priorities (see Brady,2017; Radio New Zealand, 2017b). It is alsoaimed at strengthening the ‘communication andcooperation’ capability in addition to the origi-nal objective of surveillance and monitoring(see Tauafiafi, 2017c). For Australia, this initia-tive represents a new model of support with anestimated annual cost of AU$10–15 millionbeing funded as part of the new AU$2 billiondollar Pacific Maritime Security Programsupported by the Australian Department ofDefence (Brady, 2017; Department of Defence,2018). In this way the initiative would allow theprogramme to formally link with Australia’sDefence Cooperation Program, which is respon-sible for the security and stability of a largergeographical area that comprises not only thePacific Islands region, but also Southeast Asiannations such as Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philip-pines and Timor Leste (see Tauafiafi, 2017c).

Though inconclusive at time of writing, thereare indications that PICs are accepting the newreality of their coastal waters as being underthreat from blue boats, a reality that is sociallyconstituted by the speech acts of variousregional and national actors in the last fewyears. Following the well-publicised incident intheir waters last year, the Solomon Islands Gov-ernment, for instance, formed a high-levelcross-sectoral task force to deliberate on theways to enhance interagency cooperation andcoastal community alertness. A national strategyto deal with blue boats is also being led by theMinistry of Fisheries and Marine Resourcestogether with other ministries (R. Masu, pers.comm., 2018). In countries where no officialsighting of blue boats has yet been docu-mented, there is an admission that this issuerequires close watch. Tokelau’s fisheries officer,Feleti Tulafono, cautioned, for example,

‘Whilst their transgressions may be occurringhalf a world away from Tokelau, our immediateneighbours Samoa, Tuvalu, Kiribati, CookIslands are now concerned with this new threatthat a strong and vigorous public awarenesscampaign should be developed’ Tauafiafi,2017a).

318 © 2019 The Authors. Asia Pacific Viewpoint published by Victoria University of Wellingtonand John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd

A.M. Song et al.

Discussion: Wider implications and researchagenda

In many PICs, customary marine tenure pro-vides the foundations for the rights that coastalpeople have in deciding how their marineresources are used and managed. It is thesefoundations upon which community-basedforms of management have persisted and gainedtraction as the principal mode (and scale) inwhich coastal fisheries should be governed inthe Pacific region (Johannes, 2002; Govanet al., 2006; SPC, 2015). Yet, there are someenduring and emerging issues that community-based management alone may not be able toaddress. In the face of globalisation and increas-ing demand for resources, it is useful to exam-ine one such governance challenge and itsintricate connections with larger political-economic and geographical trends (Howittet al., 2013), which we illuminate using thecase of ‘blue boats’ in the Asia Pacific.This paper has analysed some of the early

speeches and actions of national and regionalactors visible in the public communicativedomain to explore how the recent phenomenonof blue boat incursion is being positionedwithin the maritime security discourse in thePacific Island region. Based on the initial evi-dence gathered for this purpose, we posit thatblue boats and their poaching activities arebeing devised as a fresh means to strengthenregional awareness, cooperation and capacityfor maritime security. The main novelty of blueboats arguably stems from their small, rudimen-tary and even ungovernable characteristics.Such attributes pose a different set of securitychallenges compared to large-scale industrialfleets, who tend to be technically more detect-able (via VMS and on-board observers), admin-istratively traceable (via vessel registration,catch reporting and audit trails) and politicallyrecognisable (via ties to lobbyists, industries andhigh-level diplomacy). The incursion of blueboats thus invites a new way of approachingthe topic of maritime security in the region. Spa-tially, it adds a coastal dimension that repre-sents a vast shore-based area nearly impossibleto oversee using centralised means and conven-tional radar. There is also a degree of informal-ity and randomness associated with these boatsand their crew. In order to respond to the

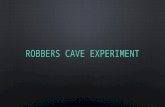

changing conditions of threats that demandfiner resolution yet broad coverage, the regionaldialogue has so far emphasised multilateralaerial surveillance capacity together with theinvolvement of fishers themselves, community-based actors and provincial authorities to reportlocal sightings (see Fig. 1; also Song, 2015 onthe idea of ‘civilian scouts’). Blue boats aretherefore bolstering the need for closer coopera-tion not only among governments and agenciesbut also including the dispersed, informal actorsresiding at lower and resource user-levels tocreate a greater network of interdependencies.From this, we aver that tackling blue boats is

becoming the newest extension of the regionalmaritime security apparatus. Aside from theadded security challenges, its securitisation(as with any intentional political endeavour)would also present opportunities for increasinginfluence for those willing to act vocally anddecisively to negotiate the risks. The recentactivities have shown that FFA and Australia, inparticular, have swiftly (and in part jointly)engaged with the issue – a securitising movefrom which these actors may derive certainorganisational and strategic benefits in years tocome. Both the Australia’s 2016 Defence WhitePaper and the 2017 Foreign Policy WhitePaper, which reaffirm enhanced commitment tosafeguarding maritime security in the Pacific, aswell as the latest consensus among PICs toexpand the Biketawa Declaration to incorporatethe non-traditional security topics includingfisheries and human and environmental security(i.e. a Regional Security Declaration to beknown as the Boe Declaration), provide a widerpolitical backdrop which would favour the con-tinued salience of blue boats in the securitydiscussion.In coming years, the actual events of the blue

boat incursion may cease due to the changingmacro and micro economic conditions motivat-ing the fishing trips as well as the controllingeffort of the Vietnamese Government and/or theeffective deterrence from the Pacific actors. Forinstance, the recent warnings of the EuropeanUnion to ban Vietnamese seafood imports hasprompted the Vietnamese Government to dem-onstrate some progress in curbing IUU fishingof its offshore fleets (L. Son, pers. comm., 2018).Yet, as long as the threat itself is maintained topersist, there will be a lingering appetite for a

© 2019 The Authors. Asia Pacific Viewpoint published by Victoria University of Wellingtonand John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd

319

Securitisation of blue boats in Asia-Pacific

security discourse and the ensuing surveillancepractice. The nature of smaller fishing vessels issuch that they are more difficult to track andaccount for, with a vast number of them origi-nating from numerous landing sites stretchedacross the Asia–Pacific. Hence, it is perhapsnot entirely unthinkable that there could be a‘Chinese version’ of the blue boats appearing inthe Pacific Islands at some point in time (seealso Wong, 2016). In recent decades, influx ofChinese loans, aids and infrastructure develop-ment has been a noticeable trend in the region(Shie, 2007; Zhang and Lawson, 2017) andarguably a contentious topic for the metropoli-tan countries such as Australia andNew Zealand in fear of losing diplomatic,

economic and even naval influence over PICs(Windybank, 2005). While how much of theChinese influence should amount to a securityconcern is unknown (and in fact not directlyessential for discussion in this paper), it mightbe worth keeping in mind the contemporaryhistory of fishing boat expansion in China, theirfrequent incursions in the nearby seas of dis-puted or foreign jurisdiction such as the YellowSea and the South China Sea, as well as theiralleged dual role as a para-military unit (Dupontand Baker, 2014; Zhang and Bateman, 2017).Thus, with potential to grow into a more flam-mable international relations issue, the threatthe small transboundary fishing boats posecould be of enduring concern to those

Figure 1. A ‘blue boat’ posterproduced for the Solomon Islands in

2017, which can be replicated for othercountries, and eventually in the locallanguages. Source: SPC (2017). [Colour

figure can be viewed atwileyonlinelibrary.com]

320 © 2019 The Authors. Asia Pacific Viewpoint published by Victoria University of Wellingtonand John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd

A.M. Song et al.

addressing maritime security in the PacificIsland region.Research on this topic would support the

wider trends observed in maritime security stud-ies. According to Bueger and Edmunds (2016),maritime security issues are increasinglycharacterised by interconnectivity across scalesand sectors transcending traditional boundariesand jurisdictional responsibilities. This meansthat the future study agenda requires criticaland expanded attention to the ways securitycooperation have become more diffuse, com-plex and diverse involving state, private andother non-state actors, including local fishingcommunities, as well as a holistic approach todeal with different but interlinked forms of mari-time crimes and risks. Furthermore, the issues ofport security, illegal fishing or environmentaldegradation remain particularly underexplored.Calling for ongoing in-depth studies that employmore sociological and interdisciplinary observa-tions (Bueger and Edmunds, 2016; Song et al.,2017), the research on the blue boats and theirsecurity implications can represent a useful con-tribution to the maritime security praxis anddebate that ultimately affects how we view andevaluate the oceans, and the transboundary per-formances within.Our initial sense-making of the blue boat

phenomenon raises a crucial set of questions forfuture empirical research, which include but arenot limited to:• What are the (geo)political, economic and

historical developments including climatechange that constitute domestic push factorsthat encourage or compel Vietnamese and otherboats and crew to venture into the Pacific? Also,what are the fishers’ internal logic and liveli-hood concerns that directly affect their motiva-tions and agency with respect to transboundaryfishing work?

� How has the Vietnamese Government’sposition on the blue boats evolved, what havebeen their stated responses and actions, whathave they achieved and what are the opportuni-ties and limitations of their control, if any?

� What are the perceptions of variousregional actors in the Pacific and theirorganisational responses on this issue (includingthe national ministries of PICs and those ofAustralia as well as inter-governmental bodiesand independent experts)? How do their

understandings and priorities vary in terms of itssecurity implications, and why? What effectdoes this issue have on regional cooperation orthe ‘Pacific Regionalism’ ethos?

� How can the claimed linkage of blue boatswith larger-scale and arguably more sinisterproblems of corporate IUU fishing, transnationalshipment of illicit goods and sea slavery andhuman rights violation be validated? Whatshould be done to reduce such risks and makethe undertaking of small fishing boats more gov-ernable? Should ‘desecuritisation’ be the goal(i.e., shifting of issues back into the mundane,normal bargaining processes without the needfor emergency measures), and if so, how?We anticipate all this should help gain a

more accurate and comprehensive grasp on thisrelatively new and under-identified phenome-non. Identifying the sources of the issue, contextand reactions and how these mesh into domi-nant narratives to produce the ongoing out-comes should be the collective endeavour of awide range of actors in the region, namely allthose concerned with the provision of food,identity, and sovereignty that coastal watersconfer upon the people of the Pacific Islands.

Acknowledgements

This work was undertaken as part of the CGIARResearch Program on Fish Agri-Food Systems(FISH) led by WorldFish. The program issupported by contributors to the CGIAR TrustFund. This work was supported by theAustralian Government through Australian Cen-tre for International Agricultural Research(ACIAR) project FIS/2016/300 and theAustralian Research Council through the ARCCentre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies.Authors thank two anonymous reviewers fortheir insightful comments on an earlier versionof the paper.

References

Adger, W.N. (2010) Climate change, human well-being andinsecurity, New Political Economy 15(2): 275–292.

Albaniel, R. (2016) PNG Fisheries Minister raises grave con-cerns about illegal fishing incursions. Pacific IslandsReport December 28. Retrieved 2 December 2017,from Website: http://www.pireport.org/articles/2016/12/

© 2019 The Authors. Asia Pacific Viewpoint published by Victoria University of Wellingtonand John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd

321

Securitisation of blue boats in Asia-Pacific

28/png-fisheries-minister-raises-grave-concerns-about-illegal-fishing-incursions

Anderson, S.C., J.M. Flemming, R. Watson and H.K. Lotze(2011) Serial exploitation of global sea cucumber fish-eries, Fish and Fisheries 12(3): 317–339.

Aqorau, T. (2000) Illegal fishing and fisheries law enforce-ment in small Island developing states: The Pacificislands experience, The International Journal of Marineand Coastal Law 15(1): 37–63.

Barclay, K., J. Kinch, M. Fabinyi, et al. (2016) Interactivegovernance analysis of the bêche-de-mer ‘fish chain’from Papua New Guinea to Asian markets. Reportcommissioned by the David and Lucile Packard Foun-dation. Sydney: University of Technology Sydney.

Barnett, J. (2017) The dilemmas of normalising losses fromclimate change: Towards hope for Pacific atoll coun-tries, Asia Pacific Viewpoint 58(1): 3–13.

Bateman, S. and J. Mossop (2010) New Zealand andAustralia’s role in improving maritime security in thePacific region, in N. Klein, J. Mossop and D.R. Rothwell (eds.), Maritime security: International lawand policy perspectives from Australia andNew Zealand, pp. 94–116. Abingdon: Routledge.

Blaha, F. (2016) Illegal fishing in the central and SouthPacific, SPC Fisheries Newsletter 151: 21–23.

Brady, S. (2017). Pacific air patrols will do more than com-bat illegal fishing. The Interpreter, 14 November.Retrieved 2 December 2017, from Website: https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/pacific-air-patrols-will-do-more-combat-illegal-fishing

Buchanan, A. (2017) Vietnamese captains say they are vic-tims of human trafficking. Solomon Star, 6 July.Retrieved 2 December 2017, from Website: http://www.solomonstarnews.com/index.php/sports/national/item/18898-vietnamese-captains-say-they-are-victims-of-human-trafficking

Bueger, C. (2013) Communities of security practice at work?The emerging African maritime security regime, AfricanSecurity 6(3–4): 297–316.

Bueger, C. (2015) What is maritime security? Marine Policy53: 159–164.

Bueger, C. and T. Edmunds (2016) Beyond seablindness: Anew agenda for maritime security studies, InternationalAffairs 93(6): 1293–1311.

Buzan, B., O. Wæver and J. de Wilde (1998) Security: Anew framework for analysis. Boulder, Colorado: LynneRienner Publishers.

Carleton, C., J. Hambrey, H. Govan, P. Medley and J. Kinch(2013) Effective management of sea cucumber fisheriesand the beche-de-mer trade in Melanesia, SPC Fisher-ies Newsletter 140: 24–42.

Carreon, B.H. (2017a) The blue threat: Vietnamese poachersare rocking the boat in the Pacific. Pacific Island Times,6 January. Retrieved 2 December 2017, from Website:http://www.pacificislandtimes.com/single-post/2017/01/06/The-blue-threat-Vietnamese-poachers-are-rocking-the-boat-in-the-Pacific

Carreon, B.H. (2017b) Vietnam asked to step up efforts to stopmarauding blue boats. Pacific Note, 6 December.Retrieved 8 May 2018, from Website: https://www.pacificnote.com/single-post/2017/12/06/Vietnam-Asked-to-Step-Up-Efforts-To-Stop-Marauding-Blue-Boats

Carreon, B.H. (2017c) Vietnamese blue boat incursionsraised anew at Manila fishery meet. Pacific IslandTimes, 4 December. Retrieved 2 December 2017, fromWebsite: http://www.pacificislandtimes.com/single-post/2017/12/04/Vietnamese-blue-boat-incursions-raised-anew-at-Manila-fishery-meet

Christensen, A.E. (2011) Marine gold and atoll livelihoods: Therise and fall of the bêche-de-mer trade on Ontong Java,Solomon Islands, Natural Resources Forum 35(1): 9–20.

Cohen, M.J. and P. Pinstrup-Andersen (1999) Food securityand conflict, Social Research 66(1): 375–416.

Cullwick, J. (2016) Blue boats – a new illegal fishing threatto Vanuatu. Vanuatu Daily Post, 12 December.Retrieved 2 December 2017, from Website: http://dailypost.vu/news/blue-boats-a-new-illegal-fishing-threat-to-vanuatu/article_51940ed4-79f9-589d-9a8f-e53a41682649.html

Cullwick, J. (2018) PIF holds maritime security consultationswith Vanuatu. Vanuatu Daily Post, 27 March. Retrieved8 May 2018, from Website: http://dailypost.vu/news/pif-holds-maritime-security-consultations-with-vanuatu/article_8df2dd47-fca4-5471-a68c-dd6abbdf2c22.html

Department of Defence (2018) Commencement of aerialsurveillance - Pacific Maritime Security Program.28 January. Retrieved 8 May 2018, from Website:https://www.minister.defence.gov.au/minister/marise-payne/media-releases/commencement-aerial-surveillance-pacific-maritime-security

Duarte, É. (2016) Brazil, the blue economy and the maritimesecurity of the South Atlantic, Journal of the IndianOcean Region 12(1): 97–111.

Dupont, A. and C.G. Baker (2014) East Asia’s maritime dis-putes: Fishing in troubled waters, The WashingtonQuarterly 37(1): 79–98.

Fabinyi, M., K. Barclay and H. Eriksson (2017) Chinese traderperceptions on sourcing and consumption of endan-gered seafood, Frontiers in Marine Science 4: 181.

Fairclough, N. (2013) Critical discourse analysis: The criticalstudy of language, 2nd edn. Abingdon: Routledge.

FFA (Forum Fisheries Agency) (2016) Keeping the Pacificwatch- 3 ‘blue boats’ nabbed as Rai Balang 2016 ends,22 April. Retrieved 2 December 2017, from Website:www.ffa.int/node/1706

FFA (Forum Fisheries Agency) (2017a) Rai Balang surveil-lance sweep nabs IUU fishers: Blue boats spotted inPNG EEZ, 17 March. Retrieved 2 December 2017,from Website: https://www.ffa.int/node/1905

FFA (Forum Fisheries Agency) (2017b) FFA, SPC Pacificworkshop sharpens focus on Vietnamese Blue Boats,5 May. Retrieved 2 December 2017, from Website:https://www.ffa.int/node/1921

Field, M. (2017) Vietnamese poachers plunder South Pacificsea cucumbers. NikkeiAsianReview, 27 February.Retrieved 2 December 2017, from Website: https://asia.nikkei.com/Economy/Vietnamese-poachers-plunder-South-Pacific-sea-cucumbers

Firth, S. (2003) Conceptualizing security in Oceania: Newand enduring issues, in E. Shibuya and J. Rolfe (eds.),Security in Oceania in the 21st Century, pp. 41–52.Honolulu: Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies.

Fletcher, G. (2004) Terrorism and security issues in thePacific, in I. Molloy (ed.), The eye of the cyclone v1:

322 © 2019 The Authors. Asia Pacific Viewpoint published by Victoria University of Wellingtonand John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd

A.M. Song et al.

Issues in Pacific security, 2nd edn, pp. 13–18. SippyDowns: PIPSA and University of the Sunshine Coast.

Fortune, G. (2006) New Zealand’s approach to Pacific secu-rity, in J. Bryant-Tokalau and I. Frazer (eds.), Redefiningthe Pacific? Regionalism past, present and future,pp. 57–65. Abingdon: Routledge.

Frazer, I. and J. Bryant-Tokalau (2006) Introduction: Theuncertain future of Pacific regionalism, in J. Bryant-Tokalau and I. Frazer (eds.), Redefining the Pacific?Regionalism past, present and future, pp. 1–23.Abingdon: Routledge.

Gillett, R. (2009) Fisheries in the economies of the PacificIsland countries and territories. Manila: Asian Develop-ment Bank.

Gillett, Preston and Associates Inc (2000) The sustainablecontribution of fisheries to food security in Oceania, inSustainable contribution of fisheries to food security.Bangkok: Asia-Pacific Fishery Commission and FAORegional Office for Asia and the Pacific Retrieved8 May 2018, from Website: www.fao.org/docrep/003/x6956e/x6956e09.htm.

Gillett, R. and M.I. Tauati (2018) Fisheries in the Pacific.Regional and national information. FAO Fisheries andAquaculture Technical Paper No. 625. Apia: FAO.

Govan, H. (2014) Monitoring, Control and Surveillance ofCoastal fisheries in Kiribati and Vanuatu. Part I: Priori-ties for action. Report for Secretariat of the PacificCommunity (SPC). Noumea: SPC Division of Fisheries,Aquacultur’e and Marine Ecosystems.

Govan, H., A. Tawake and K. Tabunakawai (2006) Commu-nity-based marine resource management in the SouthPacific, Parks 16(1): 63–67.

Hair, C., S. Foale, J. Kinch, L. Yaman and P.C. Southgate(2016) Beyond boom, bust and ban: The sandfish(Holothuria scabra) fishery in the Tigak Islands, PapuaNew Guinea, Regional Studies in Marine Science 5:69–79.

Hayward-Jones, J. (2015) Australia and security in thePacific Islands region, in R. Azizian and C. Cramer(eds.), Regionalism, security & cooperation in Oceania,pp. 67–78. Honolulu: Asia-Pacific Center for SecurityStudies.

Hoàng, L. (2017) �Ap lực gia t�ang, Việt Nam chật vật ng�andân đánh cá lậu [Increasing pressure, Vietnam strug-gled to prevent smugglers]. VOATIENGVIET, 10 June,Retrieved 28 April 2018, from Website: https://www.voatiengviet.com/a/ap-luc-gia-tang-viet-nam-chat-vat-tim-cach-ngan-chan-tau-ca-trai-phep/3894369.html[in Vietnamese]

Howitt, R., G. Lunkapis, S. Suchet-Pearson and F. Miller(2013) New geographies of coexistence: Reconsideringcultural interfaces in resource and environmental gov-ernance, Asia Pacific Viewpoint 54(2): 123–125.

Johannes, R.E. (1978) Traditional marine conservationmethods in Oceania and their demise, Annual Reviewof Ecology and Systematics 9(1): 349–364.

Johannes, R.E. (2002) The renaissance of community-basedmarine resource management in Oceania, AnnualReview of Ecology and Systematics 33(1): 317–340.

Jones, S.M. (2009) Implications and effects of maritime secu-rity on the operation and management on merchantvessels, in R. Herbert-Burns, S. Bateman and P. Lehr

(eds.), Lloyd’s MIU handbook of maritime security,pp. 87–116. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press.

Klein, N., J. Mossop and D.R. Rothwell (2010) Australia,New Zealand and maritime security, in N. Klein,J. Mossop and D.R. Rothwell (eds.), Maritime security:International law and policy perspectives fromAustralia and New Zealand, pp. 1–21. Abingdon:Routledge.

Koczberski, G., G. Curry, J. Warku and C. Kwam (2006)Village-based marine resource use and rural liveli-hoods, Kimbe Bay, West New Britain, Papua NewGuinea. TNC Pacific Island Countries Report No. 5/06.Brisbane: The Nature Conservancy, USAID, CurtinUniversity.

Macfarlane, D. (2017) The slave trade and the right of visitunder the law of the sea convention: Exploitation inthe fishing industry in New Zealand and Thailand,Asian Journal of International Law 7(1): 94–123.

Martin, T. (2005) Report on foreign fishing vessel security issuesin the Pacific Islands region. Regional Maritime Pro-gramme. Noumea: Secretariat of the Pacific Community.

McNulty, J. (2013) Western and Central Pacific Ocean fish-eries and the opportunities for transnational organisedcrime: Monitoring, control and surveillance (MCS)operation Kurukuru, Australian Journal of Maritime &Ocean Affairs 5(4): 145–152.

Movick, J. (2017) Interview in the Dateline Pacific, RadioNew Zealand, Vietnamese ’reef robbers’ not blue boats– FFA, 31 March. Retrieved 2 December 2017, fromWebsite: https://www.radionz.co.nz/international/programmes/datelinepacific/audio/201838723/vietnamese-’reef-robbers’-not-blue-boats-ffa

Murray, W.E. and J. Overton (2011) The inverse sovereigntyeffect: Aid, scale and neostructuralism in Oceania, AsiaPacific Viewpoint 52(3): 272–284.

Phòng, B.B. (2017) Đổi máu lấy hải sâm [blood transfusion]. BáoMó ̛ i, 21 August. Retrieved 28 April 2018, from Website:https://baomoi.com/doi-mau-lay-hai-sam/c/23069993.epi

PNA (Parties to the Nauru Agreement) (2016a) PNA mem-bers voice concerns over fishing management.6 December. Retrieved 2 December 2017, fromWebsite: https://www.pnatuna.com/node/381

PNA (Parties to the Nauru Agreement) (2016b) Illegal fishingby ‘blue boats’ criticized by PNA member at TunaCommission. 7 December. Retrieved 2 December2017, from Website: www.pnatuna.com/node/382

Pomeroy, R., J. Parks, R. Pollnac et al. (2007) Fish wars:Conflict and collaboration in fisheries management inSoutheast Asia, Marine Policy 31(6): 645–656.

Pomeroy, R., K.A.T. Nguyen and H.X. Thong (2009) Small-scale marine fisheries policy in Vietnam, Marine Policy33(2): 419–428.

Purcell, S.W. (2014) Value, market preferences and trade ofbeche-de-mer from Pacific Island sea cucumbers, PLoSOne 9(4): e95075.

Purcell, S.W., P. Ngaluafe, S.J. Foale, N. Cocks, B.R. Cullisand W. Lalavanua (2016) Multiple factors affect socio-economics and wellbeing of artisanal sea cucumberfishers, PLoS One 11(12): e0165633.

Purcell, S.W., D.H. Williamson and P. Ngaluafe (2018) Chi-nese market prices of beche-de-mer: Implications forfisheries and aquaculture, Marine Policy 91: 58–65.

© 2019 The Authors. Asia Pacific Viewpoint published by Victoria University of Wellingtonand John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd

323

Securitisation of blue boats in Asia-Pacific

Radio New Zealand (2017a) NZ naval ship to deploy to Fijito counter illegal fishing. April 7. Retrieved from2 December 2017, from Website: https://www.radionz.co.nz/international/pacific-news/328333/nz-naval-ship-to-deploy-to-fiji-to-counter-illegal-fishing

Radio New Zealand (2017b) Australia commits $US330 mil-lion to Pacific tuna surveillance. 31 January. Retrieved2 December 2017, from Website: https://www.radionz.co.nz/international/pacific-news/323440/australia-commits-$us330-million-to-pacific-tuna-surveillance

Rika, N. (2017) Bad boy: Vietnam earns villain status. TUNApacific, December 7. Retrieved 8 May 2018, fromWebsite: http://www.tunapacific.org/2017/12/07/bad-boy-vietnam-earns-villain-status

Rolfe, J. (2003) Australia and the security of the SouthPacific, in E. Shibuya and J. Rolfe (eds.), Security inOceania in the 21st Century, pp. 111–122. Honolulu:Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies.

Ross, R. (2009) China’s naval nationalism: Sources, prospects,and the US response, International Security 34(2): 46–81.

Shie, T.R. (2007) Rising Chinese influence in the South Pacific:Beijing’s “Island fever”, Asian Survey 47(2): 307–326.

Song, A.M. (2015) Pawns, pirates or peacemakers: Fishing boatsin the inter-Korean maritime boundary dispute and ambiv-alent governmentality, Political Geography 48: 60–71.

Song, A.M., J. Scholtens, J. Stephen, M. Bavinck andR. Chuenpagdee (2017) Transboundary research infisheries, Marine Policy 76: 8–18.

SPC (2017) ‘Blue boats’ are a problem! SPC Fisheries News-letter 153: 10.

SPC (Secretariat of the Pacific Community) (2015) A newsong for coastal fisheries – Pathways to change: TheNoumea strategy. Noumea: SPC.

Tauafiafi, F. (2017a) Pacific countries workshop focus onillegal Vietnamese Blue Boat threat. TUNApacific,4 May. Retrieved 2 December 2017, from Website:http://www.tunapacific.org/2017/05/04/escalate-pacific-countries-special-meeting-focus-on-illegal-vietnamese-blue-boat-threat/

Tauafiafi, F. (2017b) Reef Robbers: Who’s paying? Newpressures for Pacific surveillance from Vietnam’s BlueBoats. TUNApacific, 14 April. Retrieved 2 December2017, from Website: http://www.tunapacific.org/2017/04/14/reef-robbers-whos-paying-new-pressures-for-pacific-surveillance-from-vietnams-blue-boats

Tauafiafi, F. (2017c) Australia commits to Aircraft Surveillancecapability for Pacific fishery management. TUNApacific,2 July. Retrieved 2 December 2017, from Website: http://www.tunapacific.org/2017/07/02/australia-commits-to-aircraft-surveillance-capability-for-pacific-fishery-management

Taylor, J.R. and E.J. Van Every (2000) The emergent organi-zation: Communication as its site and surface.Mahwah, New Jersey: Erlbaum.

UNODC (UN Office on Drugs and Crime) (2016) Transna-tional organized crime in the Pacific: A threat assess-ment. Bangkok: UNDOC.

Vaara, E. and J. Tienari (2002) Justification, legitimization andnaturalization of mergers and acquisitions: A critical dis-course analysis of media texts, Organization 9(2): 275–304.

Voice of America (2017a) Ghi nhận từ một chuyến th�amlàng lặn hải sâm Bình Châu [Recorded from a visit toBinh Chau sea scuba diving village]. Vietnamese VOA,7 July. Retrieved 28 April 2018, from Website: https://www.voatiengviet.com/a/ghi-nhan-tu-chuyen-tham-lang-lan-hai-sam-binh-chau/3932566.html

Voice of America (2017b) Canh b :ac hải sâm [Silver seacucumber]. Vietnamese VOA, 13 June. Retrieved28 April 2018, from Website: https://www.voatiengviet.com/a/canh-bac-hai-sam/3897507.html

Voyer, M., C. Schofield, K. Azmi, R. Warner, A. McIlgormand G. Quirk (2018) Maritime security and the blueeconomy: Intersections and interdependencies in theIndian Ocean, Journal of the Indian Ocean Region 14(1): 28–48.

Wæver, O. (1995) Securitization and desecuritization, in R.D. Lipschutz (ed.), On security, pp. 46–87. New York:Columbia University Press.

WCPFC (Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission)(2018) The commission for the conservation and man-agement of highly migratory fish stocks in the westernand central Pacific Ocean. Fourteenth Regular Sessionof the Commission, Manila, Philippines, 3-7 December2017. Retrieved 8 May 2018, from Website: https://www.wcpfc.int/meetings/wcpfc14

Weick, K.E., K.M. Sutcliffe and D. Obstfeld (2005) Organiz-ing and the process of sensemaking, Organization Sci-ence 16(4): 409–421.

Windybank, S. (2005) The China syndrome [China’s grow-ing presence in the Southwest Pacific.]. Policy: A Jour-nal of Public Policy and Ideas 21(2): 28.

Wong, C. (2016) Chinese fishermen: The new globalpirates? The Diplomat, 21 June. Retrieved 2 December2017, from Website: https://thediplomat.com/2016/06/chinese-fishermen-the-new-global-pirates

Zhang, H. and S. Bateman (2017) Fishing militia, the securi-tization of fishery and the South China Sea dispute,Contemporary Southeast Asia 39(2): 288–314.

Zhang, D. and S. Lawson (2017) China in Pacific regionalpolitics, The Round Table 106(2): 197–206.

Supporting information

Additional supporting information may befound in the online version of this article at thepublisher’s website: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi//suppinfo.Table S1. List of online media articles on ‘blueboats’ from the Asia-Pacific region(in chronological order)

324 © 2019 The Authors. Asia Pacific Viewpoint published by Victoria University of Wellingtonand John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd

A.M. Song et al.

![A Conversation with Robbers - Siamese Heritage · Rajanubhab], “เรื่องสนทนากับผู้ร้ายปล้น” [A Conversation with Robbers], printed](https://static.fdocuments.net/doc/165x107/5e1b5ed9d483ab58c46935c4/a-conversation-with-robbers-siamese-rajanubhab-aoeaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaoeaaaaaaaaaaa.jpg)