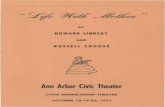

22 ANN ARBOR OBSERVER February 2005

Transcript of 22 ANN ARBOR OBSERVER February 2005

C ounty officials must be hoping that the third timewill be the charm as they approach the special mill-age election on February 22. Twice in the past eight

years, voters have rejected public safety millages. Now,another blue-ribbon committee has placed an even largerproposal before the public.

The proposed 0.75-mill tax would raise an estimated$360 million over twenty years. Of that, more than $200million would be used to build and operate 200 new jailcells. Another $10 million would be spent to replace thepresent 14A District Courthouse. Interest payments areestimated at $16 million. And over $84 million wouldfund ambitious programs to keep people out of jail.

Supporters of the millage say those alternatives to in-carceration—which include a new probation residentialfacility and better screening and treatment of mentally illoffenders—are essential. Without them, backers say, thecounty would have to build nearly twice as many addi-tional jail cells. The expanded services have also helpedthe proposal win support from the Shelter Association ofWashtenaw County and the National Alliance for theMentally Ill. But others, including some township offi-cials, question both the size and structure of the millage.And many prisoner advocates and others just don’t likethe idea of building jail cells.

The contest is being played out before a rich backdropof competing issues, old grievances, and a county govern-ment that has demonstrated a willingness to take on con-troversial measures, including aggressive spending onbuildings. County administrator Bob Guenzel calls themillage the county’s top priority. He says that if it is notapproved, the program will be enacted anyway—at theexpense of virtually every other county program.

Get out of jail freeVictor Lynn Stephens knows all about jail overcrowd-

ing. According to Ann Arbor police chief Dan Oates, the

AAPD has had contact with Stephens twenty-seven timesin the last four years, including thirteen crimes in whichhe was a suspect. On November 22, Stephens was arrest-ed on suspicion of breaking into a car in the Lakewoodsubdivision on the west side of Ann Arbor. He had itemstaken from the car in his possession and an extensivecriminal history, which included five terms in prison.Nonetheless, Stephens was immediately released on hisown recognizance. Larceny from an auto is a misde-meanor—and the jail was so crowded that it had roomonly for people charged with more serious crimes.

In the next two weeks, Stephens was arrested twomore times near cars that had been broken into, withstolen items in his possession. Both times, he was re-leased because there was no room for him in the jail. Hisone-man crime spree ended only when he had the badluck to break into a car parked in the garage of AAPDdeputy chief Gregory O’Dell. O’Dell gave chase, and

Stephens was arrested for the fourth time in two weeks.This time he was charged with home invasion—afelony—and finally jailed.

Chief Oates says Stephens’s case is typical. “We knowpeople who have been arrested twenty-plus times and arestill on the street,” he says. Magistrate Thomas Truesdellconfirms that he’s regularly forced to release people whohe believes should be in jail, because there’s no place toput them.

In a memo to the Criminal Justice Collaborative Coun-cil, the group that put the millage request together, sheriffDan Minzey says the county suffers from “suppressed jailutilization.” The problem is so severe that every policechief in the county signed a letter to the CJCC. “We strug-gle daily with whether to arrest certain serious, repeat of-fenders and whether to conduct warrant sweeps or parole-absconder arrests when we know that the person arrested. . . will likely be released because the jail is overcrowd-ed,” the chiefs wrote.

Jail overcrowding doesn’t just allow minor criminalsto continue to ply their trades while awaiting trial—it alsolets those convicted of crimes walk out before completingtheir original sentences. Between April and September2004, the jail’s average daily population was 355 prison-ers—twenty-three more than its rated capacity. As a re-sult, the sheriff was repeatedly required to declare “over-crowding emergencies” and send a list of inmates tojudges to consider for early release.

Prisoners serving time for minor crimes are chosenfirst, but even so, since 2003, 278 felons have been re-leased early. According to the police chiefs, “there arenow routine early releases of criminals with long historiesof repeating offenses.”

The county built the present jail at the county servicecenter at Washtenaw and Hogback only after being suedby the American Civil Liberties Union over conditions atthe old lockup downtown. The Hogback jail opened in1978 with 215 beds and was immediately overcrowded.Double bunking in formerly single-bunked cells and en-closing two courtyards formerly used for exercise subse-quently raised its rated capacity to the present 332 beds.Even so, it has been severely overcrowded for at least adecade.

In 1998, after a comprehensive study of county spaceneeds, the board of commissioners placed a 0.25-mill,twenty-year tax on the ballot. It was intended to pay for ajail renovation and expansion, plus a new juvenile deten-tion and day treatment center, for a total capital cost of$38 million. But Proposal 2 generated heated opposition,especially from juvenile court judge Nancy Francis, andvoters turned it down by a crushing three-to-two margin.

The county immediately regrouped with a new com-mittee and a new study. This one recommended replacingthe crumbling District 14A Courthouse on Hogback, reno-vating other satellite courthouses, and building a six-storyaddition to the main County Courthouse downtown. Thatplan died in November 2000, when voters rejected the fif-teen-year, 0.35-mill tax needed to pay for it.

In the wake of those defeats, the county has made im-pressive progress in reducing the number of people in jailawaiting trial—and not just by rejecting “misdemeanants”like Victor Stephens. By simplifying arraignment proce-dures and rearranging their schedules to give priority insetting court dates to jailed defendants, judges have cutthe average time served between arrest and sentencing byhalf, to about forty-five days. In addition, the county hasput a strong Community Corrections program into place,so judges can sentence offenders to alternatives like drugtreatment and tethers.

February 2005 ANN ARBOR OBSERVER 23

JAIL FEATURE13 COLS

CMYK

With strong feelings onall sides, the February22 vote is shaping up asa high-stakes cliff-hanger.

by Vivienne Armentrout

Since 2003, 278 felons have beenreleased early to alleviate overcrowingat the county jail. County administratorBob Guenzel says expanding the jail isthe county’s top priority.

24 ANN ARBOR OBSERVER February 2005

But at the same time those changeswere reducing the pressure on the jail, newstate policies were increasing it. Under the1998 “truthn in sentencing” law, the stateis pushing convicts out of the state prisonsystem and into county jails. That changeespecially hurts Washtenaw County, whichaccording to the CJCC has the lowest ratioof prison beds to population in the state—about 0.993 beds per 1,000 total countypopulation, compared to a state average of1.71.

Even so, developing the millage pro-posal wasn’t easy. In fact, given the recentstrains between the board of commission-ers, the sheriff, and county judges, it was amajor success just to bring all the partiestogether in the CJCC.

Budget stresses and strainsThe millage campaign comes against a

background of three other thrusts in coun-ty government: a building program thathas addressed most other needs, a strongbudget discipline in the face of state cutsand pressures from rural constituents, andtensions with the sheriff and the courts.

Despite the failure of the 1998 and2000 millages, the county has been able tofund an ambitious building program. Since1999 the administrator and commissionershave spent nearly $38 million on capitalprojects, including a new juvenile deten-tion center on Hogback and office build-ings downtown and on Zeeb Road. Re-cently, however, state revenue-sharing cutshave caused a once-healthy financial pic-ture to falter, causing a search for budgetsavings and a contraction of services.Since $35 million of the county’s $85 mil-lion 2004 general fund is allocated to pub-lic safety, it has been the single biggest tar-get for cuts—and the biggest source offriction.

Four years ago, the board eliminated“general fund” road patrols. Previously thesheriff had provided some routine policeservices throughout the county; now,deputies patrol only those municipalitiesthat contract for their services. The changeoutraged many rural residents: road patrolswere one of the few visible county servic-es they received. It also set up a long-run-ning conflict between the board and Sher-iff Minzey, who took office just as thechange was being implemented.

The change was supposed to save$650,000 a year—money that would beput into a “jail reserve fund.” In exchange,the board promised to continue subsidiz-ing contracted police services by dedicat-ing 0.5 mills (about $6.4 million in 2005)for that purpose. But while Minzey has re-duced some costs, he hasn’t come close tomeeting administrators’ targets: in 2004,

CMYK

continued

February 2005 ANN ARBOR OBSERVER 25

police services ran $845,000 over budget.In November, when the board learned ofthe overrun, several commissioners impliedthat the sheriff was guilty of bad manage-ment. Minzey appeared before the commis-sioners in December to make an angry re-buttal. He protested that the budget—whichcalled for slashing overtime by 65 per-cent—simply did not fit his department’strue operational needs.

This history of strain may explain why,in the words of one township official,Minzey is a supporter rather than an advo-cate of the jail millage proposal: he has en-dorsed it and promoted it in public, but hehas not been the leader in the effort.

Budget issues have caused tension withthe courts as well. Under state law, thecourts are a separate unit of government,and the county commission is obliged tofund them sufficiently. This situation hasled to open warfare in some counties, in-cluding a lawsuit in Washtenaw in the1980s. The local judges prevailed, and un-der the resulting agreement, the courts

submitted an overall budget and agreed tocomply with all county procedures butotherwise had full control of their own op-erations and spending.

That deal was jeopardized as the coun-ty’s budget problems mounted. In 2003county administration reduced the courts’budget—and justified the cut by identify-ing nine specific staff positions to elimi-nate. It appeared that another lawsuitmight be imminent, but that threat wasaverted after a series of high-level negotia-

tions issued in a new memorandum of un-derstanding. The commissioners reaf-firmed the judges’ authority to determinethe number and type of positions in thecourt system, and the judges agreed to re-duce their 2004–2005 budget by about$500,000.

A “community value”Since forming the CJCC last year, com-

missioners, courts, the sheriff, and countyadministration have shown remarkableunanimity and fixity of purpose in makingthe case for a millage that would not onlyaddress the infrastructure of the jail butalso lay out a broad approach to handlingaccused offenders.

The plan includes three constructionprojects. The $38 million jail expansionwould be phased in over ten years throughsystematic demolition of the existing jailand construction of new “pods,” relativelyisolated and self-contained housing units.A new assessment center would allow

arrestees to be interviewedand separated according toclassification (currentlythey are crowded togetherin small holding cells). Anew medical facility andkitchen would eventuallybe constructed, along withmany mechanical and secu-rity fixes.

Another $10 millionwould fund construction ofa new 14A District Court-house in the former HuronValley Ambulance build-ing, next to the jail on Hog-back. And $1 million of thejail budget would be usedto turn another building atthe service center into a“probation residential facili-ty.” It would house up tothirty-five probationers—

people who either havebeen released from the jail

or have been sentenced directly to the facil-ity. They would not be locked in, butunauthorized absences would lead to awarrant for rearrest. They might eventual-ly leave for Alcoholics Anonymous or oth-er special programs, and finally to seekemployment, but they would still beobliged to report to the facility and to sub-mit to drug testing.

The probation residential facility is justone of many alternatives to incarcerationthat the millage would fund. Proponentsare very proud and enthusiastic about this

TTOO LLEEAARRNN MMOORREE:: The Criminal Justice Collaborative Council has documented thestudies and deliberations leading to the millage proposal on its website,www.ewashtenaw.org/government/departments/cjcc. The highlighted fact sheet isa useful summary, and the administrator’s recommendations lay out the back-ground and the proposal in full. Other references are also available at the site.

Chuck Ream led last fall’s med-ical marijuana initiative in AnnArbor. Now he’s organizing acampaign against the millage.

26 ANN ARBOR OBSERVER February 2005

progressive, though expensive, approach.Guenzel says that without the diversionprograms, it would be necessary to build a700-bed jail instead of the targeted 532beds—but he also says that the emphasison keeping people out of jail reflects a“Washtenaw County community value.”

It has certainly helped to win the sup-port of liberal constituencies. Jeff Irwin, acounty commissioner, says he was initiallycool to the notion of a jail millage. “Whatwon me over were the mental health diver-sion and probation residential plans,” Irwinsays. “I was not excited about the prospectof spending a lot of money on a jail, butthese are programs to keep people out ofjail.” Commissioner Barbara Bergman de-scribes the alternatives as part of the coun-ty’s responsibility to its residents. “If youtake away someone’s freedom,” she says,“then you have an obligation to releasethem as someone who has the ability to bea fully functioning citizen.”

The proposed mental health programwould amplify a system already in place toassign nonviolent offenders to treatmentrather than incarceration. Treatment wouldbe either “community based,” with up toninety mentally ill individuals receivingintensive services under the supervision ofa probation officer and a team of mentalhealth professionals, or with twenty-four-hour supervision in “crisis residential”group homes staffed by nonprofit groups.

Some critics of the millage argue that ifthe mentally ill were appropriately dealtwith in the first place, they would neverfind themselves in the criminal justice sys-tem. But Kathy Reynolds, executive direc-tor of the Washtenaw Community HealthOrganization, points out that many new in-mates are young adults who haven’t yetmet state criteria to receive mental healthassistance. With added facilities and staff,offenders who are mentally ill could beidentified immediately and diverted totreatment.

The jail debateThe emphasis on alternatives has won

over some liberals who opposed the 1998jail millage. But many prisoner advocatesand others still don’t like the idea of build-ing more jail cells.

“I don’t feel confident that passing thismillage and building this jail will get us theprogramming and resources needed forpeople in our community,” says Penny Ry-der, who directs the American Friends Ser-vice Committee’s Michigan criminal justiceprogram. Ryder also suggests that Commu-nity Corrections could be used more ag-gressively to keep people out of jail.

Chuck Ream, the author of the recentsuccessful medical marijuana initiative in

Ann Arbor, is concerned that jail cells arebeing filled up with cannabis users. He isparticularly offended that the new jailcould be expanded in the future to houseas many as 800 prisoners. Ream arguesthat the county should first create a sepa-rate “drug court” that sentences personsarrested for drug-related crimes to treat-ment rather than to imprisonment. So he’sinitiating an opposition campaign, withsigns reading, “Stop the giant jail.”

Ann Arbor attorney David Cahill saysthat with crime rates falling, “now is cer-tainly not the time to be expanding thejail.” Cahill points out that according tostate reports, the total number of crimes inWashtenaw County dropped 19 percentfrom 1997 to 2003. And others turn thesuppressed-utilization concept on its head,arguing that the presence of additionalcells would encourage inappropriate sen-tencing. As publisher and Democratic ac-tivist Dave DeVarti has put it, “If youbuild it, they will come.”

Millage backers respond that the jailexpansion is actually needed to persuadeoffenders to accept alternatives to incar-ceration. Under current crowded condi-tions, arrestees will often refuse treatmentor participation in a program, knowingthat they are unlikely to go to jail, and thatif they do, they have a good chance of be-ing released early. “You’ve got to havethat hammer [the threat of jail],” saysjudge Archie Brown. For the same reason,Brown argues, a drug court would be inef-fective without a realistic threat of a jailsentence to encourage offenders to entertreatment.

Defense attorney and CJCC memberJohn Shea says that often he has counseledclients to accept judge-ordered probationwith programs to correct self-destructivebehavior, such as substance abuse treat-ment, domestic violence counseling, ag-gression management, or even high schoolequivalency or job training—only to seethem choose jail instead, knowing thatthey will soon be out without the “hassle”of participating in a program. Although“no defense attorney wants his clients togo to jail,” says Shea, “I don’t want to seethe same client back again and again forthe same offense, either.”

Some of the nearly visceral oppositionamong juvenile and prisoner advocates to

continued

Guenzel says thatwithout the diversionprograms, it would benecessary to build a700-bed jail insteadof the targeted 532beds—and that keep-ing people out of jailreflects a “Washte-naw County commu-nity value.”

February 2005 ANN ARBOR OBSERVER 27

the concept of a jail millage reflects theaftermath of 1998’s Proposal 2. JudgeNancy Francis vigorously opposed theplan to move juvenile offenders to Hog-back, arguing that it would “separate thechildren’s court from youth facilitieswhich were deliberately joined to the courtthirty years ago.” The millage failed, butFrancis’s triumph was short-lived. Thecounty built a new juvenile facility onHogback anyway, at an eventual cost ofover $9 million.

That decision still reverberates amongadvocates. Ryder says that she was totallyopposed to moving juveniles to Hogbacknear adult detention. Suzanne Shaw, a for-mer commissioner who voted againstbuilding the detention center after the fail-ure of the millage, calls the decision “aslap in the face of the voters.” But it alsoshowed Guenzel’s determination to ac-complish the county’s building goals. Staterepresentative Alma Wheeler Smith, JudgeFrancis’s sister, says she’s not aware ofany plans by Francis to oppose the currentmillage.

Selling the millageWith the stakes so high and with the

memory of two failed millages all toofresh, the CJCC is doing everything possi-ble to assure passage. Its members are fan-ning out across the county to appear be-fore every group that’s willing to hearthem, and seeking endorsements wherepossible.

At a recent board of commissionersleadership meeting, commissioner LeahGunn proclaimed her satisfaction that theAnn Arbor City Council had voted unani-mously to endorse the proposal. Anothercoup was an endorsement from the AnnArbor Area Chamber of Commerce, eventhough its message supporting the millagelisted a number of disadvantages.

Somewhat lost in the dust is the formalcampaign committee, Citizens for PublicSafety and Justice. The committee doesnot include any people from the publicsafety community, but rather real-estatefigures Albert Berriz and Del Dunbar, to-gether with philanthropist Joe Fitz-simmons, Guenzel, and commissionersRonnie Peterson and Gunn. As of mid-January, the committee was still just be-ginning to raise funds. Its manager isCJCC member Barbara Fuller, a veteran ofmany successful campaigns, including2002’s Ann Arbor Greenbelt initiative.

In some communities other millageswill also be on the February ballot, and it’suncertain how they will affect the jail pro-posal. With Ypsilanti Township seeking atotal of 8.99 mills, and much smaller re-quests in Augusta and York townships, thecity of Milan, and the Lincoln school dis-trict, voters in the eastern half of the coun-ty will have a lot of decisions to make. AnEPIC/MRA poll conducted in early De-cember and paid for by the CJCC indicatedthat 51 to 55 percent of those polled wouldvote for the proposal, once it was ex-plained to them. When Ypsilanti Townshipvoters were specifically asked whether thetownship millage request would affecttheir decision on the jail expansion mill-age, 80 percent said it would not.

Jeff Irwin concludes that passage of thejail proposal is possible but not assured.He points out the difficulty of winningspecial elections, and the importance of“getting into people’s ears” with a strongcampaign.

One objection is that the millage wouldfund operations in addition to capital proj-ects. Guenzel is careful to explain that theoperating funds would not replace the gen-eral fund dollars currently used to run thejail. Instead, the millage money would bededicated to new programming, includingadd staffing for the additional cells, theprobation residential facility, and mentalhealth services. Nonetheless, DexterTownship supervisor Pat Kelly expects thepresence of operating costs to be a majorissue with township officials. “Everyoneknows we need a jail, and everyone knowssomething needs to be done,” says Kelly,

“but they were ignoring the political reali-ties in adding operating costs.”

Guenzel counters that other recentlypassed millage-based programs—forcounty parks and the Washtenaw Interme-diate School District, for example—in-clude operations funding, and that withoutit the county would not be able to offer theexpanded programming needed to reducethe number of prisoners. But he does ac-knowledge that future county leaders willhave to decide how to continue the servic-es once the millage runs out.

The millage may also be at a disadvan-tage in rural townships, because almost alljail inmates come from the county’s urbanareas—Ann Arbor, Ypsilanti, and YpsilantiTownship. But the single biggest source ofsuspicion and ill feeling in rural areas isuncertainty about the police services sub-sidy. Kelly and others see Guenzel’s point-ed remarks about budget shortfalls if themillage fails as an implicit threat that if itdoesn’t pass, the county will reallocate thepolice subsidy to the jail.

According to Kelly, Guenzel’s threatmight induce township residents to vote forthe millage, but it could also intensify theirresentment. Superior Township supervisorBill McFarlane and his board have dis-cussed the possibility that if the subsidy isremoved, they might have to establish theirown police department. Poorer townships,however, will not have that option.

28 ANN ARBOR OBSERVER February 2005

continued

AA vviissiitt ttoo tthhee jjaaiillThe current Washtenaw County Jail is neither a gulag nor a country club. Although

it is shabby and a bit depressed in appearance, the county is trying to keep it clean.Floor tiles are replaced as they are broken, though in a different color. Walls are contin-ually repainted. Broken-down control panels—state-of-the-art when the jail opened in1978—have modern off-the-shelf electronics glued to them. The jail has passed Michi-gan Department of Corrections inspection for the last three years, and there have beenno lawsuits over conditions.

The effects of overcrowding are seen in the mattresses on the floor of the gymnasi-um, in the stacks of supplies in the hallways, and especially in the lack of separate hous-ing for different classifications of offenders. Cells intended for overnight holding beforearraignment are now being used for “special observation” of prisoners on suicide watchor under the influence of drugs or alcohol. Only two cells are left for holding. Each has anominal capacity of six prisoners, but they can hold twenty people apiece on Saturdaynight, when there are a lot of arrests.

There are only four maximum-security cells for very dangerous inmates. Andthere’s not enough space for processing new arrivals: while one arrestee is removinghis outer clothing and surrendering his personal effects in the hallway, another is beingheld in the patrol car outside. Inmates on their way to court are lined up and leg ironsapplied in the same hallway.

“Misdemeanants” dressed in green jumpsuits sit in classrooms or around televisions.Trusties in blue work in the kitchen or laundry. Felons wear orange, and their housingunits are more controlled, with an officer operating locks and lights from a booth. Mostinmates are young, in their late twenties or teens. Women are segregated from men.

The atmosphere is relatively tranquil. Jail commander Kirk Filsinger greets inmateswith a cheerful “How’re you doing?” One young man in a green jumpsuit shyly admitsthat he is back in after breaking his probation several times. He assures Filsinger hewon’t be back: “After this, it’s over.”

—V.A.

February 2005 ANN ARBOR OBSERVER 29

Voters’ dilemmaSo what will happen if the millage isn’t

approved?According to Guenzel, the county will

have no choice but to enact the entire pro-gram anyway. He argues that if the countyfails to act, it will risk lawsuits—eitherfrom prisoners over jail conditions, orfrom citizens victimized by criminals whoshould have been imprisoned—or theMichigan Supreme Court could pressureit to expand the jail. But without the mill-age, paying for the new facilities andservices would mean slashing other coun-ty programs.

The county’s capital reserve fund can-not pay debt service on a bond for morethan $15 million, and the hoped-for jailrenovation fund never materialized. Thegeneral fund is already under pressure,with 114 jobs eliminated over the last twoyears. Guenzel predicts that if the millage

is defeated, the county will have to cut 200more positions over the next four years inorder to put buildings and programs inplace. When asked what programs wouldbe hurt, he promptly names police servic-es, and also planning and environmentalprograms, outside agency funding, anddues and memberships. He says that thecuts would take the county down to abare-bones structure, providing little morethan the services mandated by state law.

But the county commission, not Guen-zel, has the authority to make those deci-sions. The four commissioners we inter-viewed don’t contradict Guenzel’s “whatif” scenario—but they don’t fully endorseit, either.

Barbara Bergman says that she “wouldwork toward a sufficient implementation”of the jail and diversion programs “thatwill doubtless cost other human servicesprograms and also police services.” JeffIrwin notes the difficulty of doing some ofthe programs if existing services have tobe cut and employees laid off, but he saysthat adding some jail beds is necessary.Conan Smith says, “We have to realizethat all necessary services are equally crit-ical to the sustainability of our communi-ty,” while Rolland Sizemore Jr. insists thatpolice services will continue to be impor-tant to his Ypsilanti Township district.

The question goes before the voters onFebruary 22. Will it prove to have some-thing for everybody, or too much for any-body? Whatever the outcome, the conse-quences are sure to be significant. n

CMYK

Even if the millage isnot approved, Guen-zel says, the countywill have not choicebut to enact the pro-gram anyway—at theexpense of virtuallyevery other service.