2014 Blossom Music Festival August 2

-

Upload

live-publishing -

Category

Documents

-

view

222 -

download

3

description

Transcript of 2014 Blossom Music Festival August 2

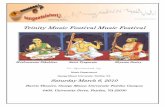

saturday August 2RAMEAU, RAVEL, & RACHMANINOFFThe Cleveland OrchestraJohannes Debus, conductorBenjamin Grosvenor, piano

2O14BLOSSOMMUSIC FESTIVALS U M M E R H O M E O F

THE CLEVELAND ORCHESTRA

2 2014 Blossom FestivalConductor

Johannes DebusGerman-born conductor Johannes Debus has served as music director of the Ca-nadian Opera Company since 2009. In opera and symphonic programs, he leads music ranging from Baroque to contemporary. He made his Cleveland Orchestra debut in August 2012. Born in southwest Germany, Johannes Debus joined the Heidelberg cathedral choir at the age of four, and later took piano, organ, and violin lessons. He ob-

tained his formal music education at the Hamburg Hoch-schule für Musik/Th eater. Mr. Debus subsequently was engaged at Frankfurt Opera, fi rst as répétiteur/rehearsal pianist and then as kapellmeister and principal conductor. During his ten-year tenure in Frankfurt, he led an extensive repertoire — including operas by Th omas Adès, Berg, Gou-nod, Massenet, Mozart, Rossini, Strauss, Verdi, and Wagner. In 2007, Johannes Debus made his English National Opera debut in a new production of Philip Glass’s Satyagra-ha and, in 2008, made his debut at the Bavarian State Opera in Munich leading Richard Strauss’s Elektra. He has also led productions with the Berlin State Opera and San Francisco Opera. Mr. Debus was invited to replace James Levine for a performance of Mozart’s Th e Abduction from the Seraglio

with the Boston Symphony Orchestra at Tanglewood in 2010. Mr. Debus made his Canadian Opera Company debut in 2008, conducting Prokofi ev’s War and Peace. Th e following year, he was named the company’s music director. His contract was recently extended through the 2016-17 season. In addi-tion to his work on the company’s mainstage productions, Mr. Debus is committed to promoting and showcasing the Canadian Opera Company orchestra’s musi-cians, and created a fi ve-concert chamber music festival, which begins its third sea-son in 2014-15. As a guest conductor, Johannes Debus has led orchestras and appeared at festivals on both sides of the Atlantic, including engagements with the Heidelberg Orchestra, Philharmonia Orchestra, Toronto Symphony Orchestra, and the Or-chestra della Toscana, as well as appearances at the Biennale di Venezia, Festival d’Automne in Paris, Lincoln Center Festival, Luminato Festival, Ruhrtriennale, Schwetzinger Festspiele, Spoleto Festival, and the Suntory Summer Festival. An advocate of new music, Mr. Debus has led a wide range of world pre-mieres and works by 20th and 21st century composers. Th ese include Salvatore Sciarrino’s Macbeth and Luciano Berio’s Un re in ascolto. Mr. Debus has guest con-ducted the Ensemble Intercontemporain, Ensemble Modern, Klangforum Wien, and Musikfabrik.

3Blossom Music Festival

Saturday evening, August 2, 2014, at 8:00 p.m.

2O14BLOSSOMMUSIC FESTIVAL

Program: August 2

T H E C L E V E L A N D O R C H E S T R A JOHANNES DEBUS , conductor

JEAN-PHILIPPE RAMEAU Suite from Les Indes Galantes(1683-1764)

MAURICE RAVEL Piano Concerto in G major(1875-1937) 1. Allegramente 2. Adagio assai 3. Presto

BENJAMIN GROSVENOR, piano

I N T E R M I S S I O N

MAURICE RAVEL Pavane for a Dead Princess[Pavane pour une infante défunte]

SERGEI RACHMANINOFF Symphonic Dances, Opus 45(1873-1943) 1. Non allegro 2. Andante con moto (Tempo di valse) 3. Lento assai — Allegro vivace

Benjamin Grosvenor’s appearance with The Cleveland Orchestra is made possible by a gift to the Orchestra’s Guest Artist Fund from Dr. and Mrs. Murray M. Bett.

This concert is dedicated to Marguerite B. Humphrey in recognition of her extraordinary generosity in supportof The Cleveland Orchestra’s 2013-14 Annual Fund.

Media Partners: WKSU 89.7 and The Plain Dealer

4 The Cleveland OrchestraAbout the Music

R A M E AU ’ S F I V E T R AG É D I E S - LY R I Q U E S were intended to rival contemporary stage drama, whether that of the Greeks or of the 18th century theater represented by Corneille and Ra-cine, with the powerful addition of “modern” music. His six opéras-ballets were, in contrast, unashamedly designed merely to entertain. Th ey made little pretense at continuity of plot, but included as wide a variety of music as possible, with the constant decoration of singing and dancing. A feast of color-ful costumes and exotic décors added a further dimension of expensive glamor. Les Indes Galantes [literally “Th e Gallant Indies”] was the fi rst of these, composed two years aft er Ra-meau’s fi rst tragédie-lyrique, and it was a huge success, being performed 64 times within two years of its premiere in August 1735. Revivals continued until 1761. When he took up composing for the stage at the age of fi ft y, Jean-Philippe Rameau was bedeviled by the accusation that he was an organist, a keyboard musician, and a famous theoretician, not an opera composer. Th ere were entrenched interests to face as well. One critic called Les Indes Galantes a “perpetual witchery.” Most Parisians were bewitched in a positive sense, however, by evocations of exotic peoples and their strange customs, for although the European aristocracy regarded other races with amusement and disdain, there were oft en implications that they did things (love, for example, and worship) in a simple, natural manner that deserved admira-tion, even before Rousseau attributed nobility to the savage. European nations are represented in the work’s Prologue, followed by four distant cultures in the four entrées that follow: Turks, Incas, Persians, and North Americans (“Les Sauvages,” from Illinois! — based on a real-life episode from 1725, when a group of “Indian Chiefs” visited Paris and danced for King Louis XV). Representing these peoples in verse, in dress, in dance, and in music was a challenge all the participant artists rose to, not least Rameau with his well-recognized command of orchestration and fanciful dances. Th is was not an ethno-graphical exercise, it was fresh, imaginative, and creative within the artistic language of the day. Th is weekend’s suite includes the following movements: Th e Ouverture belongs to the French type, with a broad

Suite from Les Indes Galantescomposed 1734-35, with additional material added in 1736

by JEAN-PHILIPPERAMEAUborn September 25, 1683Dijon, France

died September 12, 1764Paris

5Blossom Festival 2014

opening followed by a fugal allegro, this one featuring an at-tractive leaping fi gure at each entry of the subject. Th e Musette, from the Prologue, imitates the bagpipe with an unmoving drone bass, at least for the fi rst part. A middle section is in the minor key. Th e Deuxième Air pour les Bostangis (Persians) is en-ergetic, with strong unisons. Th e Incas, in the Air des Incas, are engaged in solemn worship of the sun. Th is is the movement where Rameau shows off his command of advanced harmony. Th e savages of North America dance a rather civilized pair of Menuets, the formality strengthened by trumpets and drums. Th e depiction of African slaves, in Air pour les esclaves Africains, an episode in the Turkish entrée, is mournful and entirely sympathetic if Rameau’s lovely melody says what it seems to say. Th e Air pour les amants qui suivent Bellone is fl ighty, with fl utes, and thin in texture like a delicate chase. Bellone and his friends are pursued by delectable ladies who are so of-ten represented in the 18th century as “shepherdesses.” Th e fi nal Tambourins is a swift string of notes over an almost monotone bass. Th e dance calls for “tambourins,” but it is a matter of debate whether these are tambourines or the larger long drum from the south of France. Yet a concern for authenticity seems strangely out of place when we hear the ex-otic Indes Galantes.

—Hugh Macdonald © 2014

About the Music

Rameau wrote his opéra-ballet (or ballet heroque) in 1734-35, to a libretto by Louis Fuzulier. It was fi rst performed on August 23, 1735, at Paris’s Palais-Royal by the Académie Royale de Musique. This suite chosen by conductor Johannes Debus for this weekend runs about 15 minutes in performance. The score calls for 2 fl utes, 2 oboes, 2 bassoons, 2 trum-pets, timpani, tambourin, and strings.

At a Glance

6 Blossom Music Festival

Benjamin GrosvenorBritish pianist Benjamin Grosvenor is acclaimed as a rising star among a new gene ration of pianists. When he signed to record with Decca Classics in 2011, he was the youngest British musician to ever do so. He is making his Cleveland Or-

chestra debut with this weekend’s concerts (Friday at Sever-ance Hall and Saturday night at Blossom). Benjamin Grosvenor fi rst came to prominence as the winner of the keyboard fi nal of the 2004 BBC Young Musician Competition at the age of eleven. Since then, he has performed with the London Philharmonic, New York Philharmonic, Philharmonia, RAI Torino, and the Tokyo Symphony in such venues as London’s Barbican Centre and Royal Festival Hall, Carnegie Hall, and Singapore’s Victoria Hall. At age nineteen, Mr. Grosvenor performed with the BBC Symphony Orchestra on the First Night of the 2011 BBC Proms. He returned the following year, appearing with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. His recent and upcom-

ing engagements include concerts with Berlin’s Konzerthaus Orchestra, Orquesta de Euskadi, San Francisco Symphony, and National Symphony Orchestra in Washing-ton D.C. His schedule also includes recital debuts at the Boston Celebrity Piano Se-ries, Club Musical de Québec, Salle Gaveau, Southbank Centre, and Paris’s Th éâtre des Champs-Élysées. He performs chamber music with the Elias Quartet, Endell-ion String Quartet, and Escher String Quartet. Mr. Grosvenor’s Decca discography features works by Chopin, Gershwin, Ravel, and Saint-Saëns, and transcriptions by Percy Grainger and Leopold Go-dowsky. His earlier recordings on EMI include Chopin rarities for the 200th an-niversary edition of Chopin’s complete works, as well as his debut solo recording. Among Benjamin Grosvenor’s honors are a Classic Brits Critics Award, a Diapason d’Or Jeune Talent Award, Gramophone’s Young Artist of the Year and Instrumental Award, and a UK Critics’ Circle Award for Exceptional Young Tal-ent. He has been featured in two BBC television documentaries and CNN’s Hu-man to Hero series. Th e youngest of fi ve brothers, Benjamin Grosvenor was born in 1992. His mother is a piano teacher, and he began playing at age 6. He graduated in 2012 from the Royal Academy of Music, where he was awarded the Queen’s commen-dation for excellence. Mr. Grosvenor has studied with Christopher Elton, Leif Ove Andsnes, Stephen Hough, and Arnaldo Cohen. For more information, visit www.benjamingrosvenor.co.uk.

Soloist

7Blossom Music Festival

I T WA S R AV E L’ S original plan to write a concerto for his own use. In his public appearances as a concert pianist, he had preferred mostly to play easier pieces like the Sonatine he’d written in 1903-05 and was all too conscious that his technique was not up to the more demanding works he’d created, such as Gaspard de la nuit from 1908. But, as he began creating the new work for piano and or-chestra, rather than write a piece within his own capacity, he decided to write a concerto of proper diffi culty — and simply acquire the technique to play it himself. Th us his composition hours, already long and arduous compared with his earlier fa-cility (by the end of the 1920s he was aware of the failing brain activity that cruelly silenced his last years), were interspersed with hours devoted to practicing the études of Czerny and Chopin in an unavailing attempt, at the age of 55, to perfect his digital skills (a.k.a. keyboard fi ngering, not the computer variety we think of as “digital skills” today). It was only once the work was fi nished, late in 1931, with a première not many weeks away, that Ravel abandoned his aspirations and turned to Marguerite Long to give the fi rst performance instead. Th is she did on January 14, 1932, in the Salle Pleyel, Paris, with Ravel conducting. Gustave Samazeuilh recounted that in 1911 he and Ravel spent a holiday in the Basque region of Spain (where both of them had been born) and that Ravel sketched a “Basque Con-certo” for piano and orchestra. Without the right idea for a central linking movement, Ravel abandoned the work, only to bring parts of it back to life twenty years later within the G-major concerto. Th is at least suggests a Basque origin for some of the themes, although it is easier, without any general familiarity with Basque music, to recognize that the livelier themes emerge from Ravel’s preoccupation with the brilliant percussive qualities of the piano itself, and that the languorous melodies betray his gift for giving a peculiarly sophisticated edge to the “new” language of jazz. It is striking that the sound of this concerto diff ers mark-edly from that of its sibling, the concerto for left hand, com-posed at the same time, not just in having ten fi ngers at work instead of fi ve. Here Ravel concentrated the fi ngers’ activity

Piano Concerto in G majorcomposed 1929-31, incorporating some ideas from as early as 1911

by MauriceRAVELborn March 7, 1875Ciboure, Basses-Pyrénées

diedDecember 28, 1937Paris

About the Music

8 Blossom Music Festival

in the upper reaches of the keyboard and also utilized a small orchestra, more an ensemble of soloists than a grand tutti full orchestra. Ravel asserted that he composed the G-major Concerto in the spirit of Mozart and Saint-Saëns, two composers of im-peccably classical pedigree. Th e three movements are accord-ingly laid out on the classical plan, with two quick movements embracing a slow middle one. Th e fi rst movement in its turn off ers both quick and slow sections, the latter being the occa-sion for some virtuoso melodic fl ights for solo instruments, notably the bassoon in the fi rst half, the harp and the horn in the second, while the piano is oft en required to be sweet in one hand and pungent in the other at the same time. (Gershwin’s fl attened scale, generally in the minor, is much in evidence.) Ravel spoke of writing the slow middle movement “one bar at a time” (which is nothing if not cryptic, and certainly not very enlightening), and also referred to Mozart’s Clarinet Quintet as a basis (which is scarcely more helpful, except that of course the idea of melody-with-accompaniment is promi-nent in both works). Th e style is pure, both in the simplicity of the piano style and the absence of chromatics, but it also has a constant suggestion of wrong notes in the manner of Erik Sa-tie, the wrongness in Ravel’s case being supremely calculated and . . . exactly right. Simplicity gives way to complexity and the melody returns on the english horn as the piano’s exquisite tracery continues to the end. Th e last movement is an unstoppable cascade, with the orchestra again tested to the limit, not just the soloist. Th e movement is neatly framed, with its opening clustered discords returning as a signing-off at the end.

—Hugh Macdonald © 2014

Ravel composed both of his piano concertos in 1929-31. The G-major Concerto’s fi rst performance was on Janu-ary 14, 1932, at a Ravel Festi-val concert at the Salle Pleyel in Paris, with the composer conducting the Lamoureux Orchestra; the soloist was Marguerite Long, to whom the concerto was dedicated. The concerto’s fi rst perfor-mances in North America were given concurrently on April 22, 1932, by the Boston Symphony Orchestra (con-ducted by Serge Koussevitzky and with pianist Jesús María Sanromá) and the Philadel-phia Orchestra (with conduc-tor Leopold Stokowski and pianist Sylvan Levin). This concerto runs about 20 minutes in performance. Ravel scored it for fl ute, pic-colo, oboe, english horn, E-fl at (high) and B-fl at (regular) clarinet, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, trumpet, trombone, timpani, percussion (bass drum, snare drum, cymbals, triangle, whip, tamtam, woodblock), harp, and strings.

At a Glance

About the Music

9Blossom Music Festival About the Music

T H E S P I R I T O F T H I S W O R K seems very much to be that of the French composer Erik Satie, whose titles for musical pieces are notoriously absurdist. Th e French title Pavane pour une in-fante défunte, usually rendered simply into English as “Pavane for a Dead Princess,” in fact suggests a noblewomen of Spanish origin. Ravel, at 24, was not above teasing his audience with a piece that has nothing Spanish about it (no Infanta or Infante) and is musically not really a pavane, a slow processional dance from the 16th century. Ravel dedicated this composition to the Princesse de Polignac, Paris’s most generous patron of music, who used her wealth (from Singer sewing machines) and her title (her hus-band was a composer) to support French musicians. A small piano piece such as this, composed in 1899, should be compared to the Pièces pittoresques created by Emmanuel Chabrier, which Ravel greatly admired, and some of which, like Ravel’s piece, were later orchestrated. Th e tune comes three times, orchestrated diff erently each time. Its fi rst appearance on the horn (actually intended for old-fashioned hand-horns) is marvelously evocative. Th ere are two episodes, the fi rst of which has a typically Ravelian melody with its emphasis on the second note of each phrase, shared between oboe and strings. Th e second episode explores the minor key.

—Hugh Macdonald © 2014

Hugh Macdonald lives in England and is Avis H. Blewett Professor Emeritus of Music at Washington University in St. Louis

and is a noted authority on French music. He has written books on Beethoven, Berlioz, and Scriabin.

Pavane for a Dead Princesscomposed for piano 1899, orchestrated 1910

Ravel wrote Pavane for a Dead Princess in 1899 as a solo piano piece. He created an orchestrated version in 1910, which was premiered on February 27, 1911, in Manchester, England, with conductor Henry Wood at “Gentlemen’s Concert.” This work runs 5 minutes in performance. Ravel scored it for 2 fl utes, oboe, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, harp, and muted strings.

At a Glance

by MauriceRAVELborn March 7, 1875Ciboure, Basses-Pyrénées

diedDecember 28, 1937Paris

10 Blossom Music Festival

Symphonic Dances, Opus 45composed 1940

About the Music

I N H I S Y E A R S O F E X I L E from Russia, Rachmaninoff fought a constant battle with the arbiters of taste, both in Europe and in America, who had decided that modern music had to be . . . modern. His roots were deeply planted in the soil of Russia and in the way of life he led there, and his music had evolved within the great (but relatively recent) Russian tradition, best represented by Tchaikovsky. His technique as a composer and orchestrator was unequaled, and his imagination was never dormant, but his style had little in common with the spirit of the jazz age or the various types of neo-classicism that were coming to life in the fi rst decades of the 20th century. It was perhaps because his Fourth Piano Concerto had been poorly received in 1927 — nor was the composer satis-fi ed with it himself — that Rachmaninoff cast his next piano concerto as a Rhapsody (in name) and a set of variations on a theme by Paganini (in form). Th is worked, and the public responded enthusiastically. Th e same approach brought into being the Symphonic Dances — the Th ird Symphony had simi-larly been roughly handled by the press in 1936. So that, rather than a Fourth Symphony, the new work, which turned out to be Rachmaninoff ’s last major composition, was cast originally as Fantastic Dances and then, acknowledging its true identity, as Symphonic Dances. Ballet was in his mind, in any case, because the great Rus-sian choreographer Mikhail Fokine was planning a ballet using the Rhapsody on a Th eme of Paganini, a plan which had Rach-maninoff ’s enthusiastic support. Somehow this never material-ized, nor did a Fokine ballet on the Symphonic Dances (owing to Fokine’s death in 1942, followed by Rachmaninoff ’s death a year later). Perhaps Rachmaninoff did feel this music as dance mu-sic, with the powerful stamping rhythm of the fi rst movement echoing ballets by Stravinsky and Prokofi ev, and with the fl eet waltz rhythm of the second movement suggesting Ravel. Th e fi nale is more intricate and elusive, rhythmically, for behind the restless fl ow of sounds the composer was thinking of Russian and Western chant, the latter appearing as the Dies irae from the Latin Church’s mass, frequently cited by Rachmaninoff in his music, notably in the Paganini Rhapsody. Th ere is also ref-

by SergeiRACHMANINOFFborn April 1, 1873Semyonovo, Russia

died March 28, 1943Beverly Hills,California

11Blossom Music Festival About the Music

erence to the Russian chant he had already set for chorus in his All-Night Vigil of 1915. Th ese two references emerge as intrinsic to his melodic style, deeply rooted, probably subconsciously, in the chanting of Orthodox priests that he had heard in his childhood. Melodies that move by step, or at least confi ned to narrow intervals, are readily related to plainchant, and such melodies abound in Rachmaninoff ’s works. Th e great open-ing theme of the Second Piano Concerto is of this kind. It is signifi cant also that a similar theme from the First Symphony is quoted at the end of the fi rst movement of the Symphonic Dances, played in a quiet and dignifi ed manner and standing apart from the strong pulse of the rest of the movement. The fi rst movement is a superb example of how to build the elements of structure from simple materials, in this case a descending triad, weaving under and over fi rm rhythmic sup-port and planted deeply (with endless chromatic digressions) in the key of C minor. A dialog between oboe and clarinet puts the brakes on for the second section, which is slower, cast in a remote key, and richly melodic. Here an alto saxophone introduces one of Rachmaninoff ’s endless melodies that grow and reshape them-selves in a passionate evolution, oft en hinting at a Russian fl avor. Th e middle movement is a masterpiece of elegance in a waltz rhythm full of shift s and turns, its main tune being a plaintive melody fi rst presented by english horn and oboe in partnership. Th e orchestration is dazzling, and a muted brass fanfare punctuates the movement from time to time. Th e third movement fi nale combines melancholy wist-fulness (in the Lento assai section) with rhythmic exhilaration and virtuosity in the fast sections. Th e movement is a quest for its theme, which makes the initial Allegro sound fragmentary and restless, with contributions from the piccolo and trumpet that help to form a melodic core. But this is not to be reached until aft er a lengthy return to the slower tempo, when the cel-los press the claim of something close to the Dies irae tune. Th e Allegro returns for an exuberant mélange of plainchants for the full orchestra. With so much of the fi nale devoted to gloomy Russian introspection, not remotely suggestive of dance, the whole work comes nearer to being the Fourth Symphony he never wrote, slow movement and fi nale being persuasively combined.

—Hugh Macdonald © 2014

Rachmaninoff completedhis Symphonic Dances onOctober 29, 1940. The fi rstperformance was givenby the work’s dedicatees,Eugene Ormandy and thePhiladelphia Orchestra, onJanuary 3, 1941. Symphonic Dances runs about 35 minutes. Rachmaninoff scored it for piccolo, 2 fl utes, 2 oboes,english horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, alto saxophone, 2 bassoons, contra-bassoon,4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trom-bones, tuba, timpani, percus-sion (triangle, tambourine,bass drum, side drum, cym-bals, tam-tam, glockenspiel,xylophone, bells), piano,harp, and strings.

At a Glance

Carmina BuranaO FORTUNA! Experience one of the most pop-ular masterpieces of the 20th century in Carl Orff ’s compelling tale for chorus, orch estra, and soloists. Infused with spirited rhythms, catchy melodies, and songs of love, lust, and drink — amidst the recurring change of sea-sons and the never-ending wheels of fortune and fate. With the Blossom Festival Chorus.

August 23 Saturday

The Magic of MozartWOLFGANG’S MASTERFUL MUSIC shines forth in this program of three works by Mozart himself, plus an homage to him by Tchaikovsky. Enjoy the master’s delightful tunes, his innovative sense of balance and form. Delight in the perfection of music created for listening and show. Includ-ing the popular Eine kleine Nachtmusik [“A Little Night-Music”] and the “Linz” Symphony No. 36.

August 9 Saturday

EXPERIENCE MORE BLOSSOM!See a full listing of 2014 Blossom Music Festival concerts on pages 36-37 of the Festival Book.

Yo-Yo MaONE OF THE WORLD’S most celebrated mus-icians comes to Blossom for one night only. Experience Yo-Yo Ma’s gift ed artistry inEdward Elgar’s great Cello Concerto, fi lled with majestic melody and longing, mixed with soul-stirring passion and gripping drama. Blossom favorite Jahja Ling leads this special evening.

August 16 Saturday