12415-26439-1-SM

-

Upload

victor-bowman -

Category

Documents

-

view

214 -

download

0

description

Transcript of 12415-26439-1-SM

-

PEARL CULTUREITS POTENTIAL AND IMPLICATIONS IN INDIA

K. ALACARSWAMI AND S.Z. QASIM^

Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute, Cochin-18

ABSTRACT

Pearl fisheries of India are of ancient origin. The pearl oyster resources are loca-ted mainlyin the Gulf of Kutch and Gulf of Mannar. They are subjected to wide fluctua-tions from year to year, particularly when they are exploited for natural pearls. In 1972, Vei^alodai, near Tuticorin, was selected as a site for conducting experiments on pearl oyster farming and on the development of cultured pearls. Modem method of raft culture was adopted for raising mother oysters. This method proved successful despite the try-ing sea conditions prevailing during the monsoon months. The survival rate of the pearl oysters in the farm was about 78 % during the first year. The oysters grew fast in the farm in certain seasons and remained healthy throughout the experiments. Fouling by different organisms was a serious problem and, if not checked properly, led to mortality of oysters. Settlement of the spats of pearl oyster occurred at the farm from May to July.

At Veppalodai, the techniques of producing cultured pearls from the Indian pe-arl oyster, Pittctada fucata, were developed and for the first time free, spherical cultured pearls were produced. The potential and implications of pearl culture in India have bsen discussed in relation to the situations prevailing in the pearl culture industry of other parts of the world.

INTRODUCTION

Pearl culture began in Japan in 1893 and the production of spherical cultured pearls was achieved in 1907. Since then, Japan has made several refinements in raising mother oysters, seeding and controlling the quality of cultured pearls. In fact, the technology of cultured pearls has advanced so much that it has totally over-shadowed the production of natural pearls. Raising spats of pearl oyster using hatchery techniques, introducing genetic improvements of stocks and, more recently, attempting to grow pearls by tissue culture of the mantle epithelium are some of the advances made by the Japanese scientists (Matsui, 1958; wada, 1973).

The pearl oyster resources along the Indian coasts are of considerable magnitude and fishing for natural pearls as an occupation of the coastal fishermen and divers

Present address: 1. Central Marine Fisheries Research Substation, Tuticorim-l. 2. National Institute of Ooeanogrisphy, Miramar, Panaji, Goa.

-

534 K. ALAGARSWAMI AND S. Z. QASIM

has been known since ancient times. However, despite the glorious traditions, the contribution made by the natural pearl fisheries of India to the national economy has been extremely modest and unpredictable. The earlier attempts of the Indian scientists to develop the techniques of cultured pearls remained unsuccessful (Devanesen and Chacko, 1958). In this communication, we report our efforts to produce cultured pearls at the Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute, which proved very rewarding (Alagarswami, 1974; Alagarswami and Qasim, 1974).

THE INDIAN PEARL FISHERIES

a) History The origin of Indian pearl fisheries is not fully understood. Hornell (1922)

and Arunachalam (1952) attempted to put bits of information together and wrote the history of pearl fisheries of the Gulf of Mannar. They start from the old records available in the Sanskrit and Tamil literature, mention the travelogues of foreign visitors, include the communications from among the Crown officials and finally end up with the then prevailing practices of fisheries. Two regions along the Indian coasts are Well known for the pearl oyster resources. These are the Gulf of Kutch along the northern coast of Gujarat and the Gulf of Mannar, adjoining the Tamil Nadu coast. In the beginning of the present century, the pearl fishery of the Gulf of Kutch was under the control of the Jam Saheb of Nawanagar and the fishery was conducted under certain unique rules (Hornell, 1909). In 1926, a separate department called 'Moti Khata' was organised to manage the fisheries andfinally, with the merger of the Nawanagar State with the Indian Union in 1948, the pearl fishery came under the control of the Government of Gujarat.

Hornell (1922) gives the history of the pearl fisheries of the Gulf of Mannar in detail. Glorious references to the fishery have been recorded in the 'Periplus of the Erythraean Sea' and in the works of Pliny and Ptolemy these were all written in the first and second centuries A.D. The travellers, Chau Ju Kua (1225 A.D.), Marco Polo (1260-1300 A.D.) and Friar Jordanus (1323-1330 A.D.), have described the pearl fisheries during the reign of the Pandya Kings. Jordanus wrote that about 8000 boats were employed for the pearl fisheries of Gulf of Mannar (Hornell, 1922). During the 16th century, the history of pearl fisheries is intricately connected, on the one hand, with the "ruling powers" (the Nayaks of Madura, Nawab of Carnatic and the Portuguesewith their battles for controlling the land and sea of that region) and, on the other, with the "paravas" who traditionally exploited the fisheries and the "moors'' who had an interest in pearl fishing largely for trade. The pearl fisheries seem to have been prosperous during the period of Portuguese control (1524-1658). Often, armed ships had to escort the pearling boats to give protection against piracy. The rights were then passed on to the Dutch in 1658 and later on to the British in 1796. With their unprecedented control over the pearl fisheries and full sovereign rights over the adjofining areas, the British Government abrogated the privileges previously enjoyed by the local rulers. With the Independence of the country in 1947, the rights over the pearl fishery are being fully exercised by the Government

-

- PEARL CULTURE IN INDIA 535

of Tamil Nadu. Although the need for legislation to protect, develop and enlarge the pearl fishery was felt as early as 1925, the problem was deferred'by the Gov-ernment of Madras (Raj, 1927). Thefishery continued to be operated according to the rules framed by the Department of Fisheries, Government of Madras (Tamil Nadu).

b) Distribution

The oyster that contributes to the pearl fisheries of India is Pinctada fucata. Five other closely related species have also been reported from the Indian region (Rao, 1970). The pearl oyster beds of the Gulf of Kutch, locally known as "khaddas", are located along the intertidal region of Jamnagar District (Gujarat State). The oysters are found scattered on the discontinuous reefs interspersed with sandy patches, which are exposed during the ebb tides. Easwaran et al (1969) mentions 42 important reefs, of which a few are relatively more productive than others.

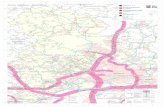

The pearl oyster resources of the Gulf of Mannar, because of the large area they occupy, assume a much greater importance. The oysters are found on the submerged rocky areas, locally called "paars" which lie at depths of 10-20m andat distances of 11-16 km from the shore. Right from the head of the Gulf on the north to Manapad in the south, there are no less than 65 paars (Fig. 1). Of these, Tho-layiram paar, the Kudamuthu and Karuwal groups of paars are the most productive beds.

In the Palk Bay also the pearl oysters have been reported in considerable numbers in some years. The paars in this area have been indicated by Mahadevan and Nayar (1973). It is very likely that future investigations may show the existence of some new and unexploited beds.

c) Exploitation

In the Gulf of Kutch, pearl fishery used to be conducted on a relatively moderate scale. The season generally commenced just after the south-west monsoon. The Department of Fisheries organised the fishery by engaging fishermen who were paid according to the number of oysters they collected. The pearls in the oysters became the property of the Government. The fishery used to be held almost every year or on alternate years from 1913 to 1939, Subsequently, it was held after every 3-4 years; but after 1966-67 there has been no fishery at all, as the oyster population became depleted (Easwaran et al, 1069). Fig. 2 gives the number of oysters fished from the Gulf of Kutch during the 25 fishing seasons extending from the year 1913 to 1967. The values of pearls realised by the Government from these pearl fisheries are also included in the figure. As can be seen from the figure, both in terms of abundance and value, the pearl oyster fishery was of a fluctuating natijre. From 1950 to 1967 the average number of oysters fished in each season was about 17,000.

-

lor

a

Q

<

30

TONDMi Pearl Fishery) ^ 1914

I N D I A (SOUTH-EAST COAST)

P A L K B A Y

GULF OF MANNAR

mg^PUipundu poor ~ ,S~Kudamulhu paar

,''-'* >-Kafuwal poor

^i^r>McifXjpad Periyapaar

:APE COMORIN

78' 30 79' Fio. 1. Distribution of pearl oyster beds in the Gulf of Mannar adjoining the Indian and Sri Lanka coasts.

-

PEARL CULTURE IN INDIA 537

The Department of Fisheries, Government of Tamil Nadu, exploited the Gulf of Mannar resource. Periodic inspections were at first conducted to estunate the oyster population. When about 60% or more of the oysters were assessed to be of three years of age and older and the pearl evaluation seemed to show a reasonable return, it Was considered desirable to conduct a fishery. The fishery was usually

Q I 80 en

70

" 60 O

Sso u. J2 S 40 I CO > o 30 CC

ui 20

o in. O

z B h I*. 00 p^ n n CO Ni-"> 9 2 . m irt

P E A R L F ISHERY Y E A R S

in io to to 'o to o ^ :* to If) to to

80 ;

70 S 8

60-

-

538 K. ALAGARSWAMI AND S. Z. QASIM

millions. In the Palk Bay, the only fishery carried out was in 1914 off Tondi which yielded 533,416 oysters (see Fig. 3).

EARLIER RESEARCHES ON PEARL OYSTER RESOURCES

Pioneering studies on the Indian pearl oyster resources were carried out by Hornell (1916,1922). These studies enabled him to make certain recommendations for the management of the natural pearl fisheries. He suggested an improvement in the inspection system, adopting regulations affecting the capture of fish from the oyster beds, transplantation of young oysters from unfavourable regions to favourable grounds and laying spat collectors on the grounds for tetter settlement of oyster spats (Hornell, 1922). He also concluded that cultivation of pearl oysters and inducing them to produce pearls Will be a sound way of making the Indian and Ceylon pearl fisheries consistently remunerative (Hornell, 1916a). ;

| 2 0

d

z

Q

to a. U J

-

> O 10

<

o z

OL

PIG. 3.

I 1900 1908 19U

CtDNDt) - P E A R L

i I

87< H5oo{2

u I

s UJ ce

150 ^

o -100

50

1926 1927 1928 1955 1956 1957 1958 1959 1960 1961

F I S H E R Y Y E A R S

Total yield of pearl oyster's and gross revenue to the Government from the pearl fisheries of Gulf of Mannar,

-

PEARL CULTURE IN INDIA 539.

After Hornell's studies, experiments oa pearl culture were mitiatedin 1933 at the Marine Fisheries Biological Station, Krusadai,'by the Depaiiment of Fisheriesi Government of Madras (Taftiil Nadu). Although the prolonged effoi'ts gave some valuable basic information on certain aspects of the biology of pearl oyster, no success was achieved in the production of"cultured pearls (Devanesen and Chidambai-am, 1956; Devanesen and Chacko, 1958; Chacko, 1970). When.the pearl oyster beds 0f the Gulf of Manpar were found to be almost barren, attempts we.re made to trans-port pearl oysters from the Persian Gulf by air in 19 50. This was done with a view^ to creating a breeding reserve on one of the beds. Heavy mortality was encountered, at various stages of transportation and finally only a few oysters could successfully be transplanted on the Tholayirampaar and at Krusadai (Devanesen and ChacJco, 1958, Appendix I).

With the technical assistance provided by the Food and Agriculture Organi-sation of the United Nations, a programme of underwater exploration of the pearl and chank beds of the Gulf of Mannar was started in 1958. In this exploration, SCUBA-diving was employed and an improved system of survey and charting of the pearl oyster beds was introduced (Baschieri-Salvadori, I960, 1961). The FAO (1962) recommended the continuation of the exploratory surveys. These surveys yielded some extremely useful ecological informations largely because of theeffortsmadebythe scientists of the Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute (Mahadevan and Nayar, 1968,1973). The physico-chemical conditions of the pearl banks during part of the above sufveys were determined by Pillai (1962 a, b).

Recent underwater surveys of the pearl oyster beds of the Gulf of Mannar showed the occurrence of oysters on some of the beds, it, therefore, became necessary to start experiments on farming of the oysters as a prelude towards developing cultured pearls.

FARMING OF PEARL OYSTERS

A detailed account of the farming procedures and the technique of producing cultured pearl have been given earlier (Alagarswami, 1970). The present efforts have been directed on these lines with suitable modifications wherever situation demanded.

a) Farm site and general sea conditions

The selection of a farm site Was made keeping in view certain factors which are conducive to farming techniques. The configuration of most of the coastline is such that ideal conditions are notavailable at any one place and, hence, the choice of a site had to be based largely on practical considerations. Veppalodai, a coastal village, about 25 km north of Tuticorin, apparently offered the following advantages: 1) the area is not being fished regularly nor does it lie along the route of fishing boats; 2) the bottom is muddy near the shore, but a little farther out the sub-stratum is hard with pieces of corals and shells; 3) it is near the pearl.oysterbeds and

-

540 K. ALAGARSWAMI AND S. Z. QASIM

4) it is away from the harbour and industrial complex of Tuticorin and, hence, it is at present free from pollution. The other important consideration was that if the experiments proved to be successful at this site, it would be possible to extend the area of operation to other neighbouring places where similar conditions prevail. At Veppalodai, the experiments commenced in December 1972 when the first raft was launched in the sea.

The rafts Were located about 1.5 km away from the shore (Fig. 4). The two small islands closeby offered very little protection to the rafts from winds and tides. The Kallar river discharges freshets into the sea during the north-east monsoon and remains dry for the rest of the year. Both the monsoons south-west and north-east influence the sea conditions considerably, Which at times become most trying for farm work. Transparency of water is limited to about 1.5 m and for most part of the year, the Water remains turbid. The surface temperature ranges from 27 to 31 C. Trichodesmium blooms appeared in March and September, but even dense con-centrations of this blue-green alga did not affect the oysters in the farm. However, oysters kept in the laboratory in sea water drawn from the inshore area during the bloom suffered mortality.

b) Collection of pearl oysters

Oysters were collected from the pearl banks both by SCUBA-diving and skin-diving. Collections were made from three oyster beds, namely Tholayiram paar, Pulipundu paar and outer Kudamuthu paar (see Fig. 1). In all, 2742 oysters ranging 3.1 - 71.6 mm d.v.m. (denoting dorso-ventral measurement of the oyster from umbo to ventral margin, excluding the growth processes) were obtained. Of these, 516 oysters were collected from Tholayiram paar (depth 15.5 m) in November '72, February and March '73, 862 oysters from Pulipundu paar (depth 14.5 m) in April and May '73 and 1364 oysters from Outer Kudamuthu paar (depth 19 m) in June '73. The oyster populations on Pulipundu and Outer Kudamuthu paars were found to be denser than on Tholayiram paar. The size-frequency distributions of the oysters collected from the three beds have been shown in Fig. 5. The oysters were transported from the pearl banks to the farm at Veppalodai.

c) Raft culture of oysters

Raft culture was employed for growing the oysters in the farm. Instead of the serial raft system, which is being used in Japan and Australia, the unit raft system was considered suitable becaiise of turbulent conditions prevailing in the sea. Five rafts have so far been used, keeping at least two at a time in the farm. The raft which was commonly used had a dimension of 6.1 m x 4.6 m. It Was constructed with teak or casuarina poles and wooden planks lashed together with coir ropes. The poles were treated With coal tar. The raft was mounted over 4 or 5 wooden barrels of 90 cm x 60 cm or empty metal drums of 200 litre capacity. The former proved to be more effective and durable. The barrels were properly painted and four of them were fixed at the corners and one at the centre with iron bands Which were

-

PEARL CULTURE IN INDIA 541

W^'^^^Z^^JZF

FIG. 4. Map of Veppalodai area showing the location of the Pearl Culture Laboratory and the pearl oyster farm. The area of the Gulf of Mannar shown gives the soundings also to indicate the potential grounds for pearl culture farms.

-

542 K. ALAQARSWAMI AND S. Z. QASIM

again tied to the poles. Wooden planks offered working space on the raft. The rafts floated well and remained above the water. Each raft was anchored to the bottom along the opposite sides with two anchor chains of 1.27 cm diameter and 14 m lopg. The iron anchors used weighed 30-40 kg each. The rafts withstood the rough seas during both th6 monsoons. After a period of 8 months, the ropes began to perish and the rafts had to be redone. However, the life of the rafts could be prolonged by using manila or nylon ropes. In Plate I, Figs 1-4 show the type of raft used together with the anchoring device etc.

Before the pearl oysters were placed on the raft, they were measured and weighed. The oysters were then arranged in sandwich-type frame nets. The net

30

20

O 10

<

20

UJ

10 o

a. 0

UJ

o 20

10

Outer Kudamuthu paar

I II n _ l l l n . Pulipundu paar

n n n n n n n XL

Tholoyiram poor

jmn o in o W3 Q

IL uS O U T o If) o tr> o (2 o iQ p in P in

DV.M. OF PEARL OYSTERS (MM)

FIG. 5. Size-frequencies of pearl oysters collected from the pearl oyster beds in the Gulf of Mannar (D.V.M. denotes dorso-ventral measurement).

-

raft.

2}

-

QASIM, PLA

which closed both the; vali'cs, 6. Ck

-

PEARL CULTURE IN INDIA 543

consisted of two frames made of steel rods of 6 mm diameter. Each frame measured 60 cm X 40 cm and it was partitioned into 5 equal sections. The frames were first painted with suitable anticorrosive paint and then these Were woven vnth synthetic twine of about 2 mm diameter so as to get uniform meshes of about 2 cm square. Two such frames were put together to form one sandwich-type frame net. In each section of the net, 6-10 oysters were arranged in a row, depending upon their size. The oysters were arranged in such a way that their hinged portions were pointing downwards andthe anterior portion of each oyster rested over the posterior portion

80

60 LU O < 1 -

-

544 K. ALAGARSWAMI AND S. Z. QASIM

If these processes and shell margins got damaged while cleaning the oysters during the period of heavy fouling, the growth of the oyster seemed to decline.

e) Fouling and boring organisms

Fouling of the pearl oysters, rafts and other implements' used in the farm is a serious problem. Although many organisms, both plants and animals, were observed to settle on the shells of oysters, the predominance of certain organisms in a particular season was noteworthy. During January to March, soon after farming of oysters began, the oysters remained fairly free from fouling, but for the growth of bryozoans and deposition of silt. From April, settlement of the larvae of bivalve, Avicula vexillum. Was very noticeable (see PI. II, Fig. 2). It was soon followed by a heavy growth of A. vexillum on the nets, virtually covering the entire surface of the nets in May and June. This made it necessary to carry out weeding operations frequently-By the middle of June, settlement of barnacles, Balanus amphitrite, was observed (PI. II, Fig. 3). As the barnacles dominated towards the end of June, the settlement of Avicula almost disappeared. From July to September, barnacles were the dominant fouling organisms. Nearly 60 barnacles, measuring 4-10 mm in diameter at their basal discs, were found settled on one side of a single oyster (PI. II, Fig. 4). The barnacles grew one over the other and in a few cases, their growth resulted in the cementing of the valves of the oysters and their consequent death (PI. II, Fig. 5). From September to November, algal growth and silt deposition was found to be fairly heavy. Barnacles again became dominant in December. The intensity of fouling seemd to have some relationship with the date of immersion of the nets-Even when Avicula and barnacle foulings were at their peaks, there were some nets relatively less affected. This probably indicates that heavy settlement of the fouling organisms was confined to brief periods.

Polychaetes and sponges were the other important boring organisms. Asci-dians, polyzoans, amphipods, opisthobranchs, crinoids etc. were also common on the oysters and the nets. Occasionally Pinna spp. and egg capsules of squids were noticed. Pinnotheres sp. was found inside some oysters. Detailed investigations on the fouling and boring organisms are in progress.

f) Survival of oysters

During the period from December 1972 to October 1973, the average survival rate of the oysters in the farm was about 78 %. Barnacle fouling caused a high mortality of oysters. Cleaning of shells during the first year could be carried out only at intervals of 2-3 months. However, to achieve a higher survival rate it would be necessary to carry out the cleaning operations more frequently.

g) Settlement of pearl oyster spat in the farm

For culture work, it is of much importance to be able to collect the young stages of the cultivated species in very large numbers. At Veppalodai farm, settlement

-

PEARL CULTURE IN INDIA 545

of the pearl oyster spat on the frame nets occurred in May 1973 When there was a heavy settlement of Avicula. Though there is a superficial resemblance between the two they could be separated after some experience by the difference in the colour pattern and shape of their shells. A total of 471 spats was collected at the farm from May to October 1973, and it seems likely that many might have been lost during the weeding operations oi Avicula. The size of the pearl oyster spats ranged 3.031.5 mm d.v.m. Fig. 6 shows the size frequencies of the spat during May, June and July-The data suggest that continuous spatfall occurs during this period.

Devanesen and Chidambaram (1956) observed a similar spat settlement at the Krusadai farm from April to July 1935. Their observations and those of ours suggest that the spats probably came as a result of spawning of the oysters at the farm itself. However, this needs confirmation. By suspending suitable spat collectors at the pearl banks and the farm it seems likely to collect large number of young oysters, which Would minunise diving operations for the collection of oysters.

TECHNOLOGY OF CULTURED PEARLS

As noted earlier, the technology of cultured pearls Was first developed in Japan, although a few other countries such as Australia, the Philippines and Burma have also started producing cultured pearls with the technical assistance provided by Japan. In India, the present series of experiments were carried out independently at the Pearl Culture Laboratory, Veppalodai. The success of these experiments has already been reported (Alagarswami, 1974).

The production of cultured pearls takes place within the tissues of the pearl oyster. If a piece of raantle tissue, cut from another oyster, is introduced along with a shell bead, acting as a nucleus, in an oyster by performing skilful surgery, it is possible to produce cultured pearls. After the operation, the epithelial cells grow and completely cover the nucleus forming a pearl sac. Thereafter, the epithelial cells begin to secrete nacre around the nucleus, just as they do over the inner surface of the valves of the pearl oyster in their natural position. This stage marks the beginning of production of cultured pearl. The final size of the pearl depends upon the size of the nucleus introduced and the duration for which it remains within the oyster.

a) Methods Pearl oysters kept on the raft were brought to the laboratory where they were

conditioned in standing sea water. Healthy oysters were then removed in batches and narcotised in menthol-sea water solution (PI. HI, Fig. 1). At the same time, one oyster was opened and portions from its mantles were cut and kept on a smooth wooden block. After removing the mucus, the mantle was further cut to smaller sizes to be used as grafts (PI. Ill, Fig. 2).

When the oysters were fully narcotised, they were taken out and washed with sea water to remove the crystals of menthol. The oysters were then fixed one by

-

546 K. ALAGARSWAMI AND S. Z. QASIM

one on a special stand and the openings of their valvesi were regulated with a special pair of tongs. An incision was made at the base of the foot of each oyster and a piece of mantle, kept ready for the purpose, was first introduced either in the gonad or in the alimentary canal. This was followed by the insertion of the nucleus (PI. Ill, Fig. 3). Soon afterwards the instruments were withdrawn and the oysters were returned to sea water in basins.

When the oysters began to show signs of recovery, frequent changes of sea water were made. A few oysters were found to eject the implanted nuclei within about 4 hours of the operation, while a few others did so in 2-3 days. For about a week, the oysters were kept in a series of wooden vats in which a continuous flow of sea water and aeration were maintained (PI. Ill, Fig. 4). The oysters were then arranged in the frame nets and returned to the raft with a new batch number.

The nuclei used in these experiments weie shell beads imported from Japan. However, ourefforts to make spherical beads of different sizes from the indigenous shells ofthechank, Xancus pyrum, Trochus niloticus. Turbo marmoratus and Tridacna spp., have yielded satisfactory results. Details of the piocedure of manufacturing shell beads have been given elsewhere (Velu, Alagarswami and Qasim, 1973). A few shell beads from our experimental batch were also used as nuclei in some oysters and these have been accepted by the oysters. The results of these experiments will be published separately.

b) Results Of the 150 oysters operated in the first series of experiments 39 have so far

been examined in three batches for evaluating the success of the technique used. The first batch of 11 oysters was examined in July 1973. Of this, five oysters were found to have ejected th^ nuclei. In four oysters, the nuclei remained uncoated with nacre, and in one, nacre deposition had commenced within 30 days of the operation and the last one in which the nucleus was 43 days old, a beautiful cultured pearl was obtained. A second batch of 16 oysters was examined in October 1973. In this, three had ejected the nuclei, in seven there was no deposition of nacreous layer on the nuclei, and six oysters produced cultured pearls. These pearls were 69-108 days old. A third batch of 12 oysters was examined in November, about 3 months after the operation. In this, two had ejected the nuclei, in three there was no deposition of nacre and seven oysters produced pearls (PI. IV, Figs 1-4). These results showed a progressive improvement in the techniques employed.

The pearls produced were free and spherical. They were generally white, ivory or golden yellow in colour. In one oyster, a steel grey pearl was obtained, but it was iiot perfectly round. The growth of pearls was rapid and the lustre was very distinct in 43 days. It became remarkably brilliant in three months. A pio-gressive growth from the original size of the nuclei, which Was of 3 mm diameter, was noticed at different time-intervals. The pearl obtained after 108 days was the largest.

-

(Facing P. 546)

-

PEARL CULTORB IN INDIA 547

These pearls are the first set oif cultured pearls produced'in India and signify the reliability of indigenous technology used. The results confirm the statements made earlier that "The Gulf of Mannar pearl oyster P.fucata should no doubt yield gbod quality cultured pearls" and "In tropical conditions Where the water is more or less uniformly warm all through the year the deposition of nacreous layer can be expected to be faster than in the Japanese waters and it may take relatively less time in our waters to get a good sized pearl" (Alagarswami, 1^70).

CONCLUSIONS

The results of the experiments indicate that there is a good scope for reyrving the pearl oyster resource by aquaculture and that an industry of cultured pearls can easily be developed in India entirely from indigenous eflbrts. However, the task is by no means as simple as the results speedily obtained might indicate. The immedi-ate aim of these experiment* was to achieve an early break-through in the technology and hence the entire operation was geared only to a few selected lines of investi-gations within a limited tinae. The investigations will now have to be carried out more intensively for establishing the technology on a firm ground as may be required for the commercial exploitation of cultured pearls.

Several biological, environmental and technological aspects are to be studied more carefully. Feeding, growth, reproduction and artificial fertilisation of the pearl oyster and rearing, larval history, spat settlement, activities of fftuling and boring organisms and parasites and diseases of the oyster need specuil attention. Environ mental factors suph as temperature, salinity, oxygen, hydrogen-ion c(mceatrationj turbidity, detritus, plankton, currents, nutrients, trace elements and pollution roust also be studied in detail. All these informations would help in assessing the quality of pearls produced and extending the pearl culture operations to other areas. Improve-ment and standardisaiion of farming equipment and methods, production of better shell teads as nuclei, fabrication of special tools for performing surgery in oysteis, mechanisation of pearl collection, optic properties of cultured pearls groWn in different area? and coUecteid at different times, are some of the problems involved. Moreover, exploratory surveys for locating new pearl oyster beds should also be taken up.

Wada (1973), while indicating the recent trends in pearl culture, technology, has drawn attention to the increasing problem of pollution in the Japanese waters. In 1970, the number of cultivators and rafts decreased to less than 22% and 27% respectively of those in 1966. Genetic improvement of the pearl oyster stocks has a.lso been engaging the attention of Japanese workers (Matsui, 1958). The decline in the pearl culture industry hais ledilo the development of-a new concept that is, pearls should be cultured exclusively in tie laboratory by employing "tissue cuitui-e of the epithelial cells of the mantle (Wada, 1973). This, if successful, would revolii* tidnize the entire technology of cultured pearl production. In Australia too, where some of the biggest and finest cultured pearls are now produced, the levisl of

-

548 K. ALAGARSWAMI AND S. Z. QASIM

production has come down because of high mortality of oysters in the farms and difficulties in attracting adequate farm labour (Franklin, 1973; Hancock, 1973).

The imports of pearls into India during the three-year period 1968-691970-71 were of the order of Rs. 8.8 millions a year. The exports of pearls from India were also of similar magnitudes. The cultured pearls constituted 57% of the imports and 95% of the imported cultured pearls were used for meeting demands within the country. Japan is the prime supplier of cultured pearls to India and accounts for about 91 % of the total imports. The Japanese pearls Which come to India are mostly those produced by the freshwater mussel, Hyriopsis schlegeli, in Lake Biwa (Butcher, 1966). In the context of the declining trends of the industry in the two major cul-tured pearl producing countries of the world, and the steady market for pearls in India, there seems an excellent opportunity for developing a cultured pearl industry within the country. Pearls have been acclaimed to give the highest return of all the marine products cultivated in coastal waters (Wada, 1973). The sporadic natural pearl fisheries of India would in no way be affected by the cultured pearl industry and it is hoped that the trade potential for both kinds of pearls would be enlarged considerably.

From the foregoing account, the potential and implications of pearl culture in India are quite evident. Its future would largely depend upon providing the answers to some of the basic questions we have raised in this conununication. It is greatly hoped that pearl culture would receive wide attention and very soon the Indian scientists, administrators and financiers would help in bringing up this technology to a level enjoyed at present only by 2-3 countries in the world.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are very grateful to Dr. M.S. Swaminathan, F.R.S., Director General of the Indian Council of Agricultural Research, for his continued interest in this work and for the amount of encouragement we received from him. Shri T.V. Venkata-raman. Director of Fisheries, Madras, made frequent visits to our laboratory when this work was in progress and showed considerable interest. Shri John Motha was kind enough to provide facilities for the establishment of a Pearl Culture Laboratory in the premises of Veppalodai Salt Corporation. Shri K. Nagappan Nayar was extremely helpful during these investigations and he and Shri S. Mahadevan helped in the selection of farm site and in the collection of pearl oysters by SCUBA-diving. Shri A. Chellam was of immense help and gave his able assistance at the farm and in the laboratory. Shri A. Srinivasan assisted in photography. Shri A. Pathrose and other crew of the launch, M. L. Chippi, gave their full co-operation at all times. We received fullest co-operation and help from the Department of Fisheries, Government of Tamil Nadu for the collection of pearl oysters without which this Work would not have been possible. We wish to record our sincere thanks to all of them.

-

PEARL CULTURE IN INDIA 549

REFERENCES

ALAOARSWAMI, K. 1970. Pearl culture in Japan and its lessons for India. Proc. Symp. Mol-lusca, n i : 975-993. Mar. Biol. Ass. India.

ALAOARSWAMI. K . 1974. Development of cultured pearls in India. Cun. Sci., 43 (7): 205-207.

ALAOARSWAMI, K . AND S. Z . QASIM. 1974. What are pearls and how are these produced? Sea-food Expt. / . , 6 (1): 110.

ARUNAC!HALAM, S. 1952. The history of the pearl fishery of the Tamil coast. Amamalai Univ, Hist. See., 8 (1): 1-206.

BASCHIERI-SALVADORI, F . 1960. Report to the Government of India on the pearl and chank beds in the Gulf of Mannar. FAO/EPTA Rep. 1119,60 pp.

BASCHIERI-SALVADORI, F . 1961. Second report to the Government of India on the pearl and chank beds in the Gulf of Mannar. FAO/EPTA Rep. 1323, 12 pp.

BUTCHER, A . D . 1966. I'earls cultured in Japan's largest freshwater lake. Austr. Fish. Newsl.^ 25 (11): 11.

CHACKO, P.I. 1970. The pearl fisheries of Madras State. Proc. Symp. Mollusca, III : 868-872. Mar. Biol. Ass. India.

DEVANESEN, D . W . AND P I . CHACKO. 1958. Report on culture-pearl experiments at the Marine Fisheries Biological Station, Krusadai Island, Gulf of Mannar. Contribution from the Marine Fisheries Biological Statipn, Krusadai Island, Gulf of Mannar, No. 5,26 pp.

DEVANESEN, D . W. AND K . CHIDAMBARAM. 1956. Results obtained at the pearl oyster farm, Krusadai Island, Gulf of M^innar, and their application to problems relating to pearl fishe-ries in the Gulf of Mannar-I. Contribution from the Marine Fisheries Biological Station, Krusadai Island, Gulf of Mannar, No. 4,89 pp.

EASWARAN, C.R., K.R. NARAYANAN AND M.S. MICHAEL. 1969. Pearl fisheries of the Gulf of Kutch. / . Bombay mt. Hist; Soc., 66 (2): 338-344.

FAO. 1962. Third report to the Government of India on the pearl and chank beds in the Gulf of Mannar. FAO/EPTA Rep. (1498), based on the work of Francesco Baschieri-Salvadori, 7 pp.

FRANKLIN, P.O. 1973. Pearl culture industry declines. Austr. Fish., 32 (4): 9-10.

GOKHALE, S.V., C.R. EASWARAN AND R . NARASIMHAN. 1954. Growth rate of the pearl oyster, Pincteida pinctada in the Gulf of Kutch with a note on the pearl fishery of 1953. / . Bom-Iwy not. Hist. Soc, 52 (1): 124-136.

HANCOCK, D . A . 1973. Kuri Bay pearls some of the finest in the world. Austr. Fish., 32 (4): 11-12.

HORNELL, J. 1909. Report to the Government of Baroda on the prospects of establishing a pearl fishery and other marine industries on the coast of Okhamandal. Report to the Oo-vernment of Barodi'on the Marine Zoology of Okhamandal in Kathiawar, Pt. I, 34 "pp. Williams and Norgate, London.

HORNELL, J. 1916 a. An explanation of the irregularly cyclic character of the pearl fisheries of the Gulf of Mannar. Madras Fish. Bull., 8: 11-22.

HORNELL, J. 19166. Report on the pearl fishery held at Tondi, 1914. Madras Fish. Bull., S: 43-92.

-

550 K. ALAGARSWAMI AND S. Z. QASIM

HoRNELL, J. 1916 c. Professor Huxley and the Ceylon pearl fishery, with a note on the forced or cultured production of free spherical pearls. Madras Fish. Bull., 8: 93-104.

HORNELL, J. 1922. The Indian pearl fishery of the Gulf of Mannar and Palk Bay. Madras Fish. Bull., 16: 1-188.

MAHADEVAN, S. AND K . N . NAYAR. 1968. Underwater ecological observations in the Gulf of Mannar off Tuticorin, VII. General topography and ecology of the rocky bottom. /. mar. biol Ass. India, 9 (1): 147-163 (1967).

MAHADEVAN, S. AND K.N. NAYAR. 1973. Pearl oyster resources of India. In: ProC. Symp. Living Resources of the Seas around India, pp. 659-671. Spl. Publ., Central Marine Fishe-ries Research Institute, Cochin.

MATSUI, Y. 1958. Aspects of the environment of pearl-culture grounds and the problems of hybridization in the genus Pinctada. In: Perspectives in marine biology, pp. 519-531. A. A. Buzzati-Traverso (Ec), University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles.

NARAYANAN, K .R . AND M. S. MICHAEL. 1968. On the relation between age and linear measure-ments of the pearl oyster, Pinctada vulgaris (Schumacher) of the Gulf of Kutch. / . Bom-bay nat. Hist. Soc, 65 (2): 444-452.

PiLLAi, CM. 1962 a. A survey of the maritime meteorology and physico-chemical conditions ofthe Indian pearl banks oJTTuticorin in the Gulf of Mannar from December 1958 to May 1959. Madras J. Fish., 1 (1): 77-95.

PiLLAi, CM. 1962 b. A review of the physico-chemical environmental conditions of the pearl banks and chank beds off Tuticorin in the Gulf of Mannar during April 1960-March 1961. Madras J. Fish., 1 (1): 96-101.

RAJ, B .S . 1927. Administration Report for the year 1925-26. Madras Fish. Bull., 21 :1-94.

RAO, K.V. 1970. Pearl oysters of the Indian region. Proc. Symp. Mollusca, III: 1017-1028. Mar. biol. Ass. India.

VELU, M . , K . ALAOARSWAMI AND S.Z. QASIM. 1973. Technique of producing spherical shell beads as nuclei for cultured pearls. Indian J. Fish., 20 (2).

WADA, K. 1973. Modem and traditional methods of pearl culture. Underwater J., 5 (1): 28-33.