1+1 ..,, ,, CENTRAL HEALTH · 2016-11-07 · JUL-30-2010 09:36 TRAVIS COUNTY ATTORNEY p. 001/001...

Transcript of 1+1 ..,, ,, CENTRAL HEALTH · 2016-11-07 · JUL-30-2010 09:36 TRAVIS COUNTY ATTORNEY p. 001/001...

JUL-30-2010 09:36 TRAVIS COUNTY ATTORNEY p. 001/001

1+1 CENTRAL HEALTH ..,, ,, CENTRAL HEAL TH

BOARD OF MANAGERS

AGENDA

Wednesday, August 4, 2010 5:30 p.m.

Central Health Administrative Offices 1111 E. Cesar Chavez Street

Austin, Texas 78702 Board Room

CITIZENS' COMMUNICATION

CONSENT AGENDA

Notice to Public

Came lo hand and posted on a Bullotin fl-Oa111 in !he Courthouse Austin, Tra11is County, Texas on !his !he i?O""" day of

"},, l;;r 20 I <5 9ana DaBcauvoir

~~~~~eou-n7"{'j_r:--'•~<.2'~·~===-"-fy,_Texa~'~Oeputy a-i, .. ··' All matters listed under the CONSENT AGENDA will be considered by the Board of Managers to be routine and will be enacted by one motion_ There will be no separate discussion of these Items unless members of the Board or persons in the audience request speclftc items be moved from the CONSENT AGENDA to the REGULAR AGENDA for discussion plior to the time the Board of Managers votes on the motion to adopt the CONSENT AGENDA.

C1. Approve minutes for the following meeting of the Central Health Board of Managers:

a. March 25, 2010

REGULAR AGENDA*

1. Receive and discuss a presentation on the HMO Feasibility Study and discuss next steps in the process.

2. Receive and discuss a long-term visioning process for Central Health, including a presentation on Federally Qualified Health Centers.

3. Confirm the next regular Board meeting date, time, and location.

•The Board of Managers may take items in an order that differs from the posted order.

The Board of Managers may consider any matter posted on the agenda in a closed meeting if there are issues that require consideration in a closed meeting and the Board announces that the item will be considered during a closed meeting.

TOTAL P.001

Board of Managers meeting

August 4, 2010

AGENDA ITEMS C1

C1. Approve minutes for the following meeting of the Central Health Board of Managers.

MINUTES OF MEETING – MARCH 25, 2010

TRAVIS COUNTY HEALTHCARE DISTRICT d/b/a CENTRAL HEALTH

BOARD OF MANAGERS MEETING

On Thursday, March 25, 2010, a regular meeting of the Central Health Board of Managers convened in open session at 5:33 p.m. in the Ned Granger Building Commissioners Courtroom, 314 West 11th Street, Austin, Texas 78701. A quorum of the Board was present. Chairperson Coopwood and Secretary Barker were present. Clerk for the meeting was Margo Davis. ___________________________________________________________________________________

CITIZENS’ COMMUNICATION

Clerk’s Notes: None.

CONSENT AGENDA

C1. Approve minutes for the following meetings of the Central Health Board of Managers: (a) December 17, 2009; and (b) January 9, 2010.

Clerk’s Notes: None. C2. Receive the March 2010 Investment Report and ratify Central health investments for

March 2010. Clerk’s Notes: None. C3. Approve the previously proposed amendments to the Bylaws of the Board of Managers of

Central Health. Clerk’s Notes: None. Manager Coleman-Beattie MOVED that the Board approve Consent Agenda Items C1 – C3.

Secretary Barker SECONDED the motion. The motion was adopted on the following vote: Chairperson Tom Coopwood For Vice-Chairperson Rosie Mendoza For Treasurer Frank Rodriguez Absent Secretary Bobbie Barker For Manager Anthony Haley For Manager Clarke Heidrick Absent Manager Donald Patrick Absent Manager Brenda Coleman-Beattie For Manager Katrina Daniel Absent

REGULAR AGENDA

MINUTES – March 25, 2010

3. Receive and discuss information regarding the Children’s Optimal Health program. Clerk’s Notes: This item was taken out of order. Manager Katrina Daniel and Manager Clarke Heidrick joined the meeting during this agenda item.

Beth Peck, Senior Healthcare Planner for Central Health, introduced Kit Abney Spelce, Acting

Director for Children’s Optimal Health, and Dr. Stephen Pont, Co-Chair of the Technical Advisory Committee for Children’s Optimal Health, noting that a two-part presentation would be made for this agenda item.

Ms. Spelce provided an overview of the current state of the organization. Children’s Optimal

Health’s mission was presented as follows: “Through a commitment of shared data, collaboration, and ongoing communication, Children’s Optimal Health is a collective leadership initiative to ensure that every child in Central Texas becomes a healthy, productive adult engaged in his or her community.” Central Health’s role as a funding charter member of Children’s Optimal Health was noted. The goal of Children’s Optimal Health and the use of Geographic Information System (GIS) mapping is to inform policy, improve operations, promote research, and mobilize the community to better the lives of children and youth by bringing together public and proprietary data.

To illustrate the value of data sharing, Dr. Pont reviewed maps that track childhood obesity for 2007-08 and 2008-09 that were created using Austin Independent School District (AISD) data on body mass index and cardiovascular fitness. The maps sort childhood obesity data according to various geographic and economic criteria and correlations to socioeconomically challenged areas were demonstrated. Dr. Pont noted that a map can also show positive and negative influences on the food environment (e.g. grocery stores and fast food restaurants), and access to possible venues for physical activity for children (e.g. parks). Further data correlation could include crime factors affecting safe access to physical activity venues and the presence or absence of ready access to fresh food. Dr. Pont discussed ways in which the maps have motivated change in schools and communities, and how action at a Board level could also have an impact on problems such as obesity.

Questions were raised by Board members regarding the source of the AISD data, along with the status of physical education generally in the public schools, the timing of intervention for childhood obesity given that risk factors develop earlier in life, and Central Health’s access to maps from various projects. In response, Dr. Pont noted that the AISD data was gathered in connection with TEA-mandated fitness testing for children in grades 3 through 12, and the scope of student participation in the fitness assessment varied according to school involvement. Data from the maps could be used to further evaluate contributing factors in geographic areas and identify effective early childhood intervention strategies for siblings and relatives of identified obese students, such as promotion of breastfeeding and reduction of passive activity. The methodology for measuring cardiovascular fitness was explained, and the potential for error in assessing a particular student’s cardiovascular fitness on a pass/fail scale was highlighted. Dr. Pont indicated that maps from the childhood obesity project and a trauma project will be shared with Central Health.

Dr. Pont also reported that Children’s Optimal Health is currently working on a pre-natal project in which birth and outcome data from hospital systems is being evaluated. The various Children’s Optimal Health projects go forward in a community summit forum where agencies and Boards participate to spur community action. Additionally, Children’s Optimal

Page 2

MINUTES – March 25, 2010

Health has received national attention by having an article on childhood obesity published in the journal Health Affairs. It was noted that HBO discussed a documentary it is producing about obesity with that organization; that documentary will broadcast in Fall 2012.

5. Receive and discuss an update on federal health reform. Clerk’s Notes: This item was taken out of order in order to allow presentation of this update

and consideration of an agenda item in Executive Session to occur prior to Manager Heidrick’s departure.

Stacy Wilson, Director of Government Affairs; Albert Hawkins, public policy consultant under contract with Central Health and CommUnityCare; and Marsha Jones, partner with the firm HillCo Partners, discussed health reform. Ms. Wilson gave a ten year overview of the healthcare reform bill and discussed implications of the legislation. Mr. Hawkins discussed the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and significant changes that will occur within six months including changes regarding pre-existing conditions, lifetime caps on private healthcare policies, the ages to which unmarried children may stay on their parents’ group insurance, changes to Medicaid and Medicare, and increased funding for community health centers. Ms. Jones offered a framework for legislature actions and the political response. Board members raised questions regarding the anticipated impact of the legislation on assistance programs, which serve a segment of the population that is targeted for federal healthcare coverage. The presenters noted continuing concern about the impact of reform on providers who accept Medicaid, despite inclusion of an increase in payment rates for primary care providers. The increased rate, as proposed, would be federally funded for a two-year period with maintenance of the increased rate falling to the states thereafter. Questions were also raised by Board members regarding provisions in the proposed reform legislation for insurance premium increases, high risk pools, and drug cost subsidies; along with the impact of the proposed legislation on healthcare for undocumented immigrants and coverage for mental health services.

8. Discuss and take appropriate action on information related to the status of the North

Central Health Center.

Clerk’s Notes: This item was taken out of order. Chairperson Coopwood announced that the Board of Managers would convene in Executive Session to discuss Agenda Item 8 under Section 551.071 of the Texas Government Code, Consultation with Attorney. The Board of Managers convened in closed session at 6:49 p.m. Manager Heidrick left the meeting during Executive Session. The Board of Managers re-convened in open session at 7:29 p.m.

3. Receive and discuss information regarding the Children’s Optimal Health program.

Page 3

MINUTES – March 25, 2010

Clerk’s Notes: The Board of Managers resumed consideration of this item following

conclusion of the Executive Session. Beth Peck, Senior Healthcare Planner, reviewed multiple data maps and explained

information the maps convey. Board members discussed with Ms. Peck how capacity of the Central Health provider network could be correlated with demand for services the various locations, and the joint planning process with CommUnityCare to yield a plan for facilities, partnerships, and service strategies as guided by the data.

1. Receive and discuss a report of the February 2010 financial statements for Central

Health.

Clerk’s Notes: John Stephens, Chief Financial Officer, discussed financial statements for Central Health for the month of February 2010 and reported that the financial condition of Central Health is strong. In response to a question from Chairperson Coopwood, Mr. Stephens stated that reimbursement of DSH / UPL funds is not anticipated during the current or upcoming fiscal year.

2. Receive and discuss the fiscal year 2009 Annual Report. Clerk’s Notes: Christie Garbe, Chief Communications and Planning Officer, and Mike

McKinnon, Communications Coordinator, presented an overview of the 2009 Annual Report. A pre-production copy of the report was presented, with final copy available by the next Board meeting. Ms. Garbe and Mr. McKinnon worked with Hahn Texas on development of the printout, graphic design, and new logo. The layout of the report was reviewed, and Ms. Garbe gave highlights of the content. Board comment was received on the choice of graphic representations rather than images of people in the 2009 report, and Ms. Garbe noted that a piece that includes such images is currently in development.

4. Discuss and take appropriate action on a Letter of Support for the City of Austin’s

application for the “Google Fiber for the Home” program. Clerk’s Notes: Manager Katrina Daniel discussed Google’s effort to place an ultra high speed

broadband network in a small number of communities in the country, the benefit of the network for the healthcare community and for Google, and a possible letter of support from Central Health.

Manager Daniel MOVED that the Board authorize the Board Chair to sign a Letter of Support on

behalf of Central Health to be included with the City of Austin’s application for the “Google Fiber for the Home” program as presented by staff. Manager Coleman-Beattie SECONDED the motion. The motion was adopted on the following vote:

Chairperson Tom Coopwood For

Vice-Chairperson Rosie Mendoza For Treasurer Frank Rodriguez Absent Secretary Bobbie Barker For

Page 4

MINUTES – March 25, 2010

Manager Anthony Haley For Manager Clarke Heidrick For Manager Donald Patrick Absent Manager Brenda Coleman-Beattie For Manager Katrina Daniel For 6. Receive and discuss the CEO’s report on the following District activities: (a) procurement

activity; (b) communications/outreach statistics for February 2010; (c) the MAP Program, including March enrollment and activities; and (d) an update on the Community Planning Initiative.

Clerk’s Notes: Patricia Young Brown, President and Chief Executive Officer, gave a report on particular District activities. The report included public presentations by staff on various topics such as healthcare reform, and increasing Medical Assistance Program enrollment. Board members discussed with staff the possibility of having, in addition a MAP enrollment chart, a chart reflecting approved Sliding Fee Scale applications. Final resolution of this matter is subject to changes being made to eligibility and enrollment processes.

7. Confirm the next regular Board meeting date, time, and location. Clerk’s Notes: Chairperson Coopwood announced that the next regular Board meeting is

scheduled to be held on Thursday, April 8, 2010, at 5:30 p.m., in the Cesar Chavez Building, Board Room, 1111 East Cesar Chavez Street, Austin, Texas, 78702.

There being no further discussion on agenda items, Manager Coleman-Beattie MOVED that the meeting adjourn. Manager Haley SECONDED the motion. The motion was adopted on the following vote:

Chairperson Tom Coopwood For Vice-Chairperson Rosie Mendoza For Treasurer Frank Rodriguez Absent Secretary Bobbie Barker For Manager Anthony Haley For Manager Clarke Heidrick Absent Manager Donald Patrick Absent Manager Brenda Coleman-Beattie For Manager Katrina Daniel For The meeting adjourned at 8:21 p.m.

Page 5

MINUTES – March 25, 2010

Page 6

___________________________________ Tom Coopwood, Chairperson Central Health Board of Managers ATTESTED TO BY: ___________________________________ Bobbie Barker, Secretary Central Health Board of Managers

Board of Managers meeting

August 4, 2010

AGENDA ITEMS 1

1. Receive and discuss a presentation on the HMO Feasibility Study and discuss next steps in the process.

August 4, 2010

Presented By Dennis Edmonds, PresidentDennis Edmonds & Associates, LLC

HMO Feasibility Study Update

Presentation to Board of Managers

2

Presentation Outline

• Stakeholder Discussion Highlights

• HMO Flow of Funds Overview

• Feasibility Study Dashboard

3

Reasons For a Non-Profit Community Based HMO

• Rapidly growing Medicaid population• Alternative to 2 for-profit health plans• Expand patient access• Promote preventive care and a medical home • Coordinate care and social services • Link public and private resources• Reinvest profits in the community• Central Health uniquely positioned to sponsor

HMO

4

Key Themes

• Central Health is respected in community• There is a need for a community-based HMO• Expanding patient access is critical• Coordinated approach and leveraging of

public/private resources would be beneficial• Opportunities to collaborate abound • Frequent changes in eligibility status can create

problems/bad debt• For the most part, Medicaid patients take more

time to serve than commercial

5

Key Themes - Continued

• Medicaid reimbursement is inadequate• There is a shortage of primary/specialty care

providers – and some are not willing to see Medicaid patients

• Everyone is preparing for healthcare reform• It may be possible to leverage FQHC funding• HMO must be fiscally sound and well managed• Strong community outreach will be required• Link medical care with mental health and social

services

6

HMO Flow of Funds Overview

• HMO Perspective• Health Exchange Perspective• HHSC Perspective• Central Health MAP Perspective

7

Central Health HMO Perspective

Central Health HMO

Urgent Care Centers

Central Health Health ExchangeHHSC

Specialists

PCPs

CommUnitycare

Ancillary Providers

Reinsurer

Hospitals

Administrator

Pharmacy (PBM)

Mental Health Central Health

Medical Expenses Admin. Expenses

ASO Fees $Medicaid Premium $ Other Plan Premium $

Claims Reserves

HMO Admin.

$ $

$ $

8

Health Exchange Perspective

Health Plans

Health ExchangeFederal Subsidies

Individuals Small Groups

Administrator

Premiums $

$ $

Subsidized Premium $

e.g. Central Health HMO

9

HHSC Perspective

Health Plans

HHSC

Federal Funds

Administrator

$

$

Premium $

State Funds

Rebate $

10

Central Health MAP Perspective

Central Health

Breckenridge Lease Pmts & Other

Central Health HMO

$

$ ASO Fee

Property Tax

Providers

Claim $

Administrative Services

11

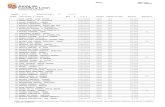

HMO Feasibility Study Dashboard Phase 1

Activity Status Results Next StepsStakeholder Meetings

40% •17 of 20 Initial Target Interviews

–Providers–Elected Officials–Community Organizations–Educational Institutions

•Preliminary Feedback Favorable•Expanded Target List to 44

•Additional Interviews•Finalize Results

Network Strategy 60% •Researched Delivery System•Competitor Network Assessment•Network Overview Spreadsheet•Basic Network Strategy

•Confirm Hospitals•Finalize Network Strategy

Strategic Objectives 10% •Initial Discussions •Alternative Strategies•Recommendations

12

HMO Feasibility Study Dashboard Phase 2

Activity Status Results Next StepsHealth Care Reform Assessment

50% •Research•Display Key Provisions

•Additional Research•Final Summary

Preliminary Financial Plan

10% •Flow of Funds•Roles & Responsibilities Matrix

•Financial Assumptions•Proforma P&L

Other Health Care Districts

10% •Initial Staff Discussions•Identified 5 Districts•Targeted Key Contacts

•Conduct Meetings•Lessens Learned•Recommendations

13

HMO Feasibility Study Dashboard Phase 3

Activity Status Results Next StepsCompetitor Assessment

0% •NA •Update Preliminary Assessment

HHSC Contract Interest

0% •NA •Confirm HHSC Interest

Marketing Strategy 0% •NA •Update Preliminary Assessment

Enrollment Forecast 0% •NA •Marketing Assumptions•3-Year Monthly Forecast

14

HMO Feasibility Study Dashboard Phase 4

Activity Status Results Next StepsLegal / Regulatory Plan

0% •NA •Detailed Plan & Assumptions

Governance, Organization & Staffing Plan

0% •NA •Detailed Plan & Assumptions

Marketing Plan 0% •NA •Detailed Plan & Assumptions

Network Plan 0% •NA •Detailed Plan & Assumptions

Operations and IT Plan

0% •NA •Detailed Plan & Assumptions

Medical Management Plan

0% •NA •Detailed Plan & Assumptions

Detailed Financial Plan

0% •NA •Detailed Breakeven Analysis

15

Open Discussion

• Key Issues To Explore• Questions and Information Needed• Next Steps

Learn more about us at:

www.traviscountyhd.org

Board of Managers meeting

August 4, 2010

AGENDA ITEMS 2

2. Receive and discuss a long-term visioning process for Central Health, including a presentation on Federally Qualified Health Centers.

Memo

To: Central Health Board of Managers From: Beth Peck, Senior Healthcare Planner CC: Patricia A. Young Brown, Christie Garbe Date: July 29, 2010 Re: Preparation for Board Meeting This is to provide you with an overview of the long-range visioning discussion planned for the August 4, 2010 board meeting. The discussion will focus on the planning question – “How does Central Health best utilize CommUnityCare and its associated federally qualified health center (FQHC) status as a resource for the community?” To frame the discussion, staff will be presenting a very high-level overview of what a federally qualified health center is as well as the relationship between Central Health and CommUnityCare. Following this presentation, Jackie Leifer, Partner with Feldesman Tucker Leifer Fidell LLP, will be returning to discuss a number of opportunities available to FQHCs through the health reform legislation, including additional funding, medical schools, accountable care organizations, and teaching centers. I have attached the informational sheet that Ms. Leifer provided at our May 27, 2010, meeting along with some background materials that Ms. Leifer sent to provide more in-depth information on some of these issues. Finally, staff will conclude the discussion of this item by facilitating a dialogue with the Board around the following questions –

• What is the Board’s opinion on extending FQHC status to other community primary care providers through affiliation as a strategy for more fully supporting community health care services?

• Which of the opportunities mentioned is the Board most interested in pursuing? • What additional information does the Board feel is needed to help determine how best to use

the FQHC asset that we have?

I hope that you find the attached information useful for next week’s discussion. As always, thank you for your commitment to Central Health and to this planning process.

Travis County HealthCare District Opportunities to Access Additional Federal Resources in Support of the Community’s

Health Care Safety Net

May 27, 2010

Longstanding Safety Net Grant Programs • Section 330

o FY2010 Budget $2.19 billion o President’s FY2011 Budget proposes a $290 million increase for the Section 330

program • Ryan White • Other (e.g., Title X)

American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA)

• Signed into law on February 17, 2009 • $2 billion in grants to FQHCs to support the provision of comprehensive primary and

preventive health care to an increasing number of patients; create or retain thousands of jobs; and enable FQHCs to address pressing capital improvement needs, such as construction, repair, renovation, and equipment purchases (including health information technology – HIT – systems)

• $1.5 billion for Community Health Center Capital Programs

Texas Home Health Grant • $25 million in grants for eight pilot projects, each of which will receive $1 – 2 million • Target population: minimum 5,000 Medicaid kids with special needs • Encourages collaborations • See “Health Home Grant Discussion” document for additional information

Health Reform

• Signed into law on March 23, 2010 • New funding for FQHCs

o Allocates $11 billion to FQHCs over the next 5 years, which includes $1.5 billion for capital projects (FY 2011 - $1.0 billion; FY 2012 - $1.2 billion; FY 2013 - $1.5 billion; FY 2014 - $2.2 billion; and FY 2015 - $3.6 billion; there is no annual breakdown for the capital projects funds)

o It is anticipated that HRSA will issue a request for New Access Point applications this summer, with expansion opportunities to follow shortly thereafter

• National Health Service Corps

o Allocates $1.5 billion over five years for the National Health Service Corps, which will place an estimated 15,000 primary care providers in communities with health professional shortages (FY 2011 - $290 million; FY 2012 - $295 million; FY 2013 - $300 million; FY 2014 - $305 million; and FY 2015 - $310 million)

1

• Title VII Teaching Health Centers Development Grants

o Grants will be awarded to cover the costs of establishing or expanding primary care residency training programs (i.e., family medicine, internal medicine, pediatrics, internal medicine-pediatrics, obstetrics and gynecology, psychiatry, general dentistry, pediatric dentistry and/or geriatrics), including costs associated with curriculum development; recruitment, training and retention of residents and faculty; accreditation by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, the American Dental Association, or the American Osteopathic Association; and faculty salaries during the development phase

$230 million over 5 years

• Other New Programs and Demonstration Projects

o Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMI) (must begin carrying out its duties no later than January 1, 2011)

Purpose of CMI is to test innovative payment and service delivery models (e.g., patient-centered medical home models, community-based health teams to support small-practice medical homes by assisting the PCP in chronic care management, risk-based comprehensive payment to providers)

Preference is for models that improve the coordination, quality, and efficiency of healthcare services

$10 billion is appropriated during FY 2011-2019

o Community Health Teams and Patient-Centered Medical Homes Grants Authorizes grants or contracts to states to support the establishment of

health teams that support primary care practices, including OB/GYN practices

Model of care that includes: • Personal physicians • Whole person orientation • Coordinated and integrated care • Safe and high-quality care through evidence-informed

medicine, appropriate use of HIT “Health teams” must:

• Include interdisciplinary, inter-professional team of health care providers

• Support patient-centered medical homes • Collaborate with local primary care providers to coordinate

disease prevention, chronic disease management, transitioning between health care settings, and case management

• Demonstrate the "capacity to implement and maintain health information technology . . . to facilitate coordination among the

2

members of the health team and affiliated primary care practices”

• Provide other support necessary for primary care providers to improve quality of care

o Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs)

Medicare Shared Saving Program (begins no later than January 1, 2012)

• Eligible ACOs may be composed of group practices, networks of individual practices, partnerships or joint venture arrangements between hospital and practitioners, hospitals employing practitioners, and other groups of providers/suppliers as determined by HHS

• Providers must meet certain criteria, including quality measurements, to form an ACO

• ACO must: o Be accountable for the quality and cost of healthcare

services for the Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries assigned to it

o Include primary care professionals o Have a formal legal structure o Have a shared governance structure and engage in joint

decision-making o Have a leadership and management structure that

includes clinical and administrative systems o Demonstrate that it meets patient-centeredness criteria

• Eligible ACOs must have at least 5,000 Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries and must commit to participate for three years

• Participating ACO will be eligible to receive payments from savings if it achieves quality and cost containment standards

o Medicaid Global Payment System Demonstration (effective fiscal years 2010 through 2012)

Authorizes demonstration projects in the Medicaid program Global safety net hospital systems or networks would move from a

FFS structure to a global capitated payment model Limited to 5 states

o Community-Based Collaborative Care Networks

Grants will be awarded to support community-based collaborative care networks; the network is described as a consortium of health care providers with a joint governance structure (including providers within a single entity) that provides comprehensive coordinated and integrated health care services for low-income populations

3

4

Must include a hospital and all federally qualified health centers located in the community

Must have a joint governance structure

o Co-locating Primary and Specialty Care in Community-Based Mental Health Settings

Authorizes grants and cooperative agreements to community mental health centers to establish demonstration projects for the provision of coordinated and integrated services to special populations through the co-location of primary and specialty care services in community-based mental and behavioral health settings

$50,000,000 for FY2010 and such sums as may be necessary for FY2011 through FY2014

Core Health Center Requirements and Unique FQHC Benefits

Range of Collaboration Opportunities

• Referral arrangements • Co-location arrangements • Integration of services of multiple providers (e.g., behavioral health) • Transfer existing sites to health center license • Establish new sites • Teaching agreements • “ER diversion” programs • Retail clinics • Community benefit grants

ISSUE BRIEF Accountable Care Organizations

March 2009

Reforming Provider Payment Moving Toward Accountability for Quality and Value

Introduction The ongoing debate over health care reform in the United States has expanded from targeted concerns about the millions of Americans without health insurance to broader consideration of gaps in quality, rising health care costs, and the structure of a system that is failing to address either problem. Dramatic variations in healthcare spending that bear little correlation to quality indicate that our current system neither rewards nor encourages higher-value care. For example, we spend three times more per Medicare beneficiary in certain geographic regions than in others – and yet the quality and outcomes of care are no better. In addition, many preventive services are underused, and adherence to proven-effective therapies for many chronic diseases is low. Medical errors and other safety problems remain too common, accounting for many thousands of deaths and billions of dollars in health care costs. All of these gaps in care are reinforced by Medicare’s current payment systems, which tend to promote high-volume and high-intensity care regardless of quality, and do not support innovative approaches to coordinating care or preventing avoidable complications or services. The Need for a New Payment Model and Principles for Payment Reform Increasing awareness of these problems has resulted in a growing array of public- and private-sector initiatives to promote efforts by providers to improve care and to foster greater accountability for both quality and cost. While there is ongoing debate over the specific form that such approaches should take and how to implement them around the country, these efforts are marked by growing consensus on several guiding principles for reform. First, there is increasing agreement on the need for local accountability for quality and cost across the continuum of care. The consistent provision of high-quality care – particularly for those with serious and chronic conditions – will require the coordination and engagement of multiple health care professionals across different institutional settings and specialties. The health care system must not only facilitate, but also encourage such coordination. Second, a successful approach to achieving greater accountability must be viable across the diverse practice types and organizational settings that characterize the U.S. health care system and should be sufficiently flexible to allow for variation in the strategies that local health systems use to improve care. Third, successful reform will require a shift in the payment system from one that rewards volume and intensity to one that promotes value (improved care at lower cost), encourages collaboration and shared responsibility among providers, and ensures that payers – both public and private – offer a consistent set of incentives to providers.

Finally, with increased accountability on the part of providers must come greater transparency for consumers. Measures of overall quality, cost, and other aspects of performance relevant to consumers will facilitate informed choices of both providers and services and increase consumers’ confidence in the care they are receiving as their providers face different incentives. Many of the payment reforms that have been proposed or are already in use – for example, bundled payments, disease management, and pay for performance – represent meaningful steps toward greater accountability. The next step is accountability for care that leads to better outcomes and lower costs at the person level, with support for the infrastructure required to provide high-quality, coordinated care. The Accountable Care Organization Model The Accountable Care Organization (ACO) model establishes a spending benchmark based on expected spending. If an ACO can improve quality while slowing spending growth, it receives shared savings from the payers. This model is well-aligned with many existing reforms, such as the medical-home model and bundled payments, and also offers additional support (and accountability) to the provider organization to enable them to deliver more efficient, coordinated care. This approach has been implemented in programs like Medicare’s Physician Group Practice (PGP) Demonstration, which has shown significant improvements in quality and savings for large group practices. Because the groups receive a share of the savings beyond a threshold level, steps like care coordination services, wellness programs, and other approaches that achieve better outcomes with less overall resource use result in greater reimbursement to the providers. These steps thus “pay off” and are sustainable in a way that they are not under current reimbursement systems. In addition, the shared savings approach provides an incentive for ACOs to avoid expansions of health care capacity that are an important driver of both regional differences in spending and variations in spending growth, and that do not improve health. The ACO approach also builds on current reform efforts that focus on one key group of providers, as in the medical-home model, or on a discrete episode of care, as in bundled payments. On their own, these initiatives may help strengthen primary care and improve care coordination, but they do not address the problem of supply-driven cost growth highlighted by the Dartmouth group. If adopted within a framework of overall accountability for cost and quality as is envisioned in the ACO model, both the medical home and bundled payment reforms would have added incentives to support not only better quality, but also lower overall spending growth (see Table 1). By shifting the emphasis from volume and intensity of services to incentives for efficiency and quality, ACOs provide new support for higher-value care without radically disrupting existing payments and practices. The ACO model builds on current provider referral patterns and offers shared savings payments, or bonuses, to providers on the basis of quality and cost. A wide variety of provider collaborations can become ACOs assuming that they are willing to be held accountable for overall patient care and operate within a particular payment and performance measurement framework. Examples include existing integrated delivery systems, physician networks such as independent practice associations, physician-hospital organizations, hospitals that have their own primary-care physician networks, and multispecialty group practices. Alternatively, primary-care groups or other organizations that provide basic care could contract with specialized groups that provide high-quality referral services with fewer costly complications.

2

Table 1 Comparison of Payment Reform Models

Accountable

Care Organization

(Shared Savings)

Primary Care Medical Home

Bundled Payments Partial Capitation Full Capitation

General strengths and weaknesses

Makes providers accountable for total per-capita costs and does not require patient “lock-in.” Reinforced by other reforms that promote coordinated, lower-cost care

Supports new efforts by primary-care physicians to coordinate care, but does not provide accountability for total per-capita costs

Promotes efficiency and care coordination within an episode, but does not provide accountability for total per-capita costs

Provides “upfront” payments that can be used to improve infrastructure and process, but provides accountability only for services/providers that fall under partial capitation, and may be viewed as too risky by many providers/patients

Provides “upfront” payments for infrastructure and process improvement and makes providers accountable for per-capita costs, but requires patient “lock-in” and may be viewed as too risky by many providers/ patients

Strengthens primary care

directly or indirectly

Yes – Provides incentive to focus on disease management within primary care. Can be strengthened by medical home or partial capitation to primary-care physicians

Yes – Changes care delivery model for primary-care physicians allowing for better care coordination and disease management

Yes/No – Only for bundled payments that result in greater support for primary-care physicians

Yes – Assuming that primary care services are included in the partial capitation model allows for infrastructure, process improvement, and a new model for care delivery

Yes – Gives providers “upfront” payments and changes the care delivery model for primary-care physicians

Fosters coordination

among all participating

providers

Yes – Significant incentive to coordinate among participating providers

No – Specialists, hospitals and other providers are not incentivized to participate in care coordination

Yes (for those within the bundle) – Depending on how the payment is structured, can improve care coordination

Yes– Strong incentive to coordinate and take other steps to reduce overall costs

Yes– Strong incentive to coordinate and take other steps to reduce overall costs

Removes payment

incentives to increase volume

Yes – Adds an incentive based on value, not volume

No – There is no incentive in the medical home to decrease volume

No, outside the bundle – There are strong incentives to increase the number of bundles and to shift costs outside

Yes/No – Strong efficiency incentive for services that fall within the partial capitation model

Yes – Very strong efficiency incentive

Fosters accountability for total per-capita costs

Yes – In the form of shared savings based on total per-capita costs

No – Incentives are not aligned across provider, no global accountability

No, outside the bundle, no accountability for total per-capita cost

Yes/No – Strong efficiency incentive for services that fall within partial capitation

Yes – Very strong accountability for per-capita cost

Requires providers to bear risk for excess costs

No – While there might be risk-sharing in some models, the model does not have to include provider risk

No – No risk for providers continuing to increase volume and intensity

Yes, within episode – Providers are given a fixed payment per episode and bear the risk of costs within the episode being higher than the payment

Yes – Only for services inside the partial capitation model

Yes – Providers are responsible for costs that are greater than the payment

Requires “lock-in” of patients

to specific providers

No – Patients can be assigned based on previous care patterns, but includes incentives to provide services within participating providers

Yes – To give providers a PMPM payment, patients must be assigned

No – Bundled payments are for a specific duration or procedure and do not require patient “lock-in” outside of the episode

Yes (for some) – Depending on the model, patients might need to be assigned to a primary-care physician

Yes – To calculate appropriate payments, patients must be assigned

3

Regardless of specific organizational form, the ACO model has three key features:

1. Local Accountability. ACO entities will be comprised of local delivery collaborations that can effectively manage the full continuum of patients’ care, from preventive services to hospital-based and nursing-home care. Their patient populations are comprised of those who receive most of their primary care from the primary-care physicians associated with the ACO (see Figure 1). (As noted above, ACOs may include a range of specialists, hospitals, and other providers, or may contract or collaborate with them in other ways.)

Multi‐Specialty Group Practice

ACO Model 3

Hospital

Specialty Group

PCP Group

ACO Model 1

Community Hospital

Specialty Group

PCP Group

ACO Model 2

Home Health Services

Mental Health Facility

Tertiary Care Facility

Specialty Physicians

Specialty Hospital

Figure 1

ACOs Can Be Configured in Different Ways(Some care will likely be delivered outside of the ACO)

2. Shared Savings. ACO-specific expenditure benchmarks will be based on historical trends

and adjusted for patient mix. Contingent on meeting designated quality thresholds, ACOs with expenditures below their particular benchmark will be eligible for shared savings payments, which can be distributed among the providers within the ACO. These shared savings allow for investments – in health IT or medical homes, for example – that can in turn improve care and slow cost growth (see Figure 2).

Projected Spending

Actual Spending

Shared Savings

Spending Benchmark

Launch of “Illustrative” ACO

Figure 2

Shared Savings Derived from Spending Below Benchmarks That Are Based on Historical Spending Patterns

3. Performance Measurement. Valid measurement of the quality of care provided through

ACOs will be essential to both ensuring that cost savings are not the result of limiting necessary care and promoting higher-quality care. Such measurement should include meaningful outcome and patient-experience data.

4

Laying the Foundation for Successful Implementation

While the ACO framework holds promise for improving quality, cost, and overall efficiency, it does create some important implementation issues. It is worth highlighting some factors that can improve the likelihood of success. Engagement of a broad range of key local stakeholders, such as payers, purchasers, providers, and patients alike, can provide momentum for ACOs. A demonstrated history of successful innovation and reform with respect to health IT adoption and clinical innovations, for example, may also be a good foundation for further ACO reforms. Having a structural foundation in place at the outset will also facilitate the transition to an ACO. Key factors include patient populations that are sufficient in size to permit reliable assessment of expenditures and quality performance relative to benchmarks, in order to calculate shared savings. Additional key elements include some degree of integration – either formal or virtual (i.e., for the purposes of the ACO) – within the delivery system and the capacity for collecting and reporting on the performance of participating providers. Finally, having an agreement and process in place for distributing shared savings will be critical in terms of presenting an attractive proposition to providers – that is, a real opportunity to generate additional payments in return for improved care – and rewards genuine improvements in efficiency. Key Design Components While consideration of the more technical aspects of implementation are beyond the scope of this overview, a brief description of several key design questions highlights the decisions that will need to be made at the ACO level through negotiations with participating payers:

• Organization of the ACO. The form and management of the ACO need to be well-defined. ACO “leaders” who will drive improvements in care and efficiency must be identified from the start.

• Scope of the ACO. The specific providers involved in ACOs are likely to include primary-care

physicians and may also include selected specialists as well as hospitals and other providers. Such decisions about the scope of providers to be included will clearly shape many of the technical aspects of the ACO, referral patterns, and other behavioral changes induced by the ACO itself.

• Spending and quality benchmarks. Spending benchmarks must be projected with sufficient

accuracy based on historical data (or other comparison groups) and savings thresholds to provide confidence that overall savings will be achieved. Sufficient measures of quality to provide evidence of improvement are also essential.

• Distribution of shared savings. Elements of the distribution of savings that will be subject to

negotiation include the percentage split between providers and payers, for example 80/20 or 50/50, and the specific agreement governing how the savings will be distributed among the ACO providers.

5

Looking Ahead: The Promise of ACOs The ACO model is receiving significant attention among policymakers and leaders in the health care community, not only because of the unsustainable path on which the country now finds itself, but also because it directly focuses on what must be a key goal of the health care system: higher value. The model offers a promising approach for achieving this goal without requiring radical change in either the payment system or current referral patterns. Rather, fee-for-service remains in place, and most physicians already practice within natural referral networks around one or a few hospitals. By promoting more strategic and effective integration and care coordination, the ACO model holds substantial promise as a reform that offers a potential win-win for providers, payers, and patients alike. For a more technical discussion of the ACO model, including budget implications, see:

• CBO, Budget Options, Volume I: Health Care (December 2008), pp. 72-74 (Option 37, “Bonus Eligible Organizations”).

• Fisher, Elliott, Mark McClellan, John Bertko, Steven Lieberman, Julie Lee, Julie Lewis, and

Jonathan Skinner. “Fostering Accountable Health Care: Moving Forward in Medicare.” Health Affairs Web Exclusive, January 27, 2009: w219-w231.

6

Can Accountable Care Organizations Improve the Value of Health Care by Solving

the Cost and Quality Quandaries?

Timely Analysis of Immediate Health Policy IssuesOctober 2009

Kelly Devers and Robert Berenson

Introduction In the current health reform discussions, accountable care organizations (ACOs) have been proposed as a novel way to slow rising health care costs and to improve quality in the traditional Medicare program and perhaps other public and private insurance programs. However, for many, it is not clear what ACOs are and whether and how they differ from other past reform approaches intended to achieve the same goals. The ACO concept is confusing partly because it is a concept with a history, one that is rapidly evolving and for which the terminology seems to keep changing. In fact, as the Issue Brief will show, different reform ideas have now been joined under the rubric of ACO.

The primary purposes of this Issue Brief are to provide insight into what ACOs seem to represent and whether they potentially offer a new and improved way to reform U.S. provider payment and delivery systems, with an emphasis on their application in Medicare. First, we clarify what ACOs generally are, including the current concept’s genesis and important dimensions on which ACOs might vary. Second, we discuss what is new about the current ACO concept compared to previous reform concepts, such as “accountable health plans” or Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs) and provider-sponsored organizations (PSOs) that were established for Medicare in the Balanced Budget Amendment (BBA) of 1997.

Third, we identify key ACO program features and issues policymakers are grappling with and about which there are different and even divergent viewpoints. These include: (1) the ACO definition and qualifying criteria, such as what kinds of providers must be included and whether an ACO is different from a patient-centered medical home (PCMH); (2) whether an ACO program should be voluntary or mandatory for providers; (3) similarly, whether beneficiaries should be assigned to ACOs or should elect to participate in one; (4) alternative ACO payment methods and their respective strengths and weaknesses; and, (5) quality measurement and monitoring. Decisions about these program features and issues will strongly influence providers and patients’ reactions to the ACO concept.

Finally, we discuss several major implementation challenges, specifically, participation of and possible untoward impact on other payers and the new roles, responsibilities, and capabilities for providers and government. We also summarize some of the pointed skepticism that some have leveled at the ACO concept and consider whether this is another example of a concept advanced more by wishful thinking than by empirically based policy analysis.

We conclude that ACOs are no game changer in the short run because they require resolution of some challenging and complex issues as well as significant provider and policymaker learning, but nonetheless, they are important to try.

If done well, an ACO program could build on lessons learned from and since the managed care era of the 1990s, get critical provider payments and delivery system changes underway, and perhaps in the long run move us beyond reliance on what many consider a dysfunctional fee-for-service (FFS) payment system.

What is an ACO?Fundamentally, the ACO concept couples provider payment and delivery system reforms in an attempt to solve the “chicken and egg” problem.1 Many believe that to bend the cost curve while improving quality, we must reform the provider payment system first, because it pays for volume rather than value. Others hold that it is impossible to change the payment system to achieve the desired objectives unless delivery system reform first produces organizations capable of handling an altered payment system. They point to the need for health care professionals, now usually working in separate institutional settings, to work collaboratively and to demonstrate their capacity for handling new payment approaches. To avoid the quandary of where to start first—provider payment or delivery system reform—the ACO concept attempts to combine them.

More specifically, ACOs can generally be defined as a local entity and a related set of providers, including at least primary care physicians, specialists, and hospitals, that can be held accountable for the cost and quality of care delivered to a defined subset of traditional

Timely Analysis of Immediate Health Policy Issues 2

Medicare program beneficiaries or other defined populations, such as commercial health plan subscribers.2 The primary ways the entity would be held accountable for its performance are through changes in traditional Medicare provider payment featuring financial rewards for good performance based on comprehensive quality and spending measurement and monitoring. Public reporting of cost and quality information to affect public perception of an ACO’s worth is another way of holding the ACO accountable for its performance.

Proponents generally view three ACO characteristics as essential. These characteristics include: (1) the ability to provide, and manage with patients, the continuum of care across different institutional settings, including at least ambulatory and inpatient hospital care and possibly post acute care; (2) the capability of prospectively planning budgets and resource needs; and, (3) sufficient size to support comprehensive, valid, and reliable performance measurement.3 Table 1 summarizes the diverse entities that could serve as an ACO, solely or in combination, including their capacity on the first two criteria.

Diverse entities could serve as an ACO, alone or in combination with each other, the collective serving as a local provider umbrella organization, system, or network (see figure 1). Shortell and Casalino4 identify five different types of

existing organizations that could either exclusively serve as an ACO in a local geographic area, or more likely lead or be part of an ACO led by another provider organization in the area. These existing provider organizations include (1) various types of physician groups or physician-centered organizations, namely multispecialty group practices (MSGs) and interdependent physician organizations (IPOs)—what most people refer to as an independent practice association (IPA); (2) hospital-centered organizations, namely hospital medical staff organizations (MSOs) and physician-hospital organizations (PHOs); and (3) Health Plan-Provider Organization or Networks (HPPNs). The latter is similar to a particular type of HMO, specifically one that contracts with one or more IPAs or with independent physician practices. However, rather than discussing HPPNs which can already participate in Medicare as a Medicare Advantage (PA) plan, we discuss organized or integrated delivery systems (ODSs or IDSs) more narrowly.5

Fisher and his team6 also acknowledge that this range of existing provider organizations could surely serve as ACOs, but they also introduce the idea that a new type of organization,7 fostered by analysis of Medicare claims data and comprised of local hospitals and the physicians who work in and around them, could also form ACOs. It is this “virtual” organization concept

that spurred the recent ACO interest based on the view that these less formal organizations could develop relatively quickly and throughout the heterogeneous forms of U.S. health care delivery.

Together, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC), the organization that advises Congress on payment and related policies for Medicare, and Fisher provided the impetus for the current concept and interest in ACOs, building on two developments—an early, positive evaluation of the Medicare Physician Group Practice (PGP) Demonstration that relied on an FFS-based payment model8 and analysis by Fisher that patients cared for by particular physician groups flowed to or clustered at particular hospitals.9 The latter analysis suggested to some that a virtual, extended hospital medical staff could be held accountable for total spending and the quality of care for patients who obtain their care from this set of physicians, similar to the way that the MSGs in the PGP demonstration were being held accountable in determining their eligibility for financial bonuses for performance.10

Others have followed with their own versions of ACOs, sometimes using different terminology and offering somewhat different prescriptions for their design features. For example, in the House of Representatives

Table 1. Potential ACO Models and Their Characteristics

Provider TypeAbility to Provide or Manage

Care Across Continuum

Ability to Plan Budgets and Resource Needs (Accept and manage non-FFS payment)

Provider Inclusiveness Level of Performance

Accountability

IPA Low/Medium Medium High Medium

Multispecialty Group Medium/High Medium Low/Medium Medium/High

Hospital Medical Staff Organization

Medium Low/Medium Medium Low/Medium

Physician-Hospital Organization (PHO)

Medium/High Medium/High Low/Medium Medium/High

Organized or Integrated Delivery Systems

Medium/High Medium/High Medium Medium/ High

Virtual approach-Extended Hospital Medical Staff

Medium Low/Medium High Low

*Based on the literature about these types of organizations.

Timely Analysis of Immediate Health Policy Issues 3

Tri-Committee on Health Reform draft legislation that set up ACO demonstrations,11 the definition of an ACO is quite broad, and the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services would delineate a more specific definition and qualifying criteria when proceeding to solicit demonstration participants. Qualifying criteria would have to delineate, for example, what legal structure would be acceptable for permitting the ACO entity and its constituent providers to receive and distribute payments and the minimum number and types of physicians needed in an ACO. The Senate Finance Committee Chairman’s Mark also uses a quite broad ACO definition, but articulates more specific qualifying criteria, leaving less discretion for the Secretary in designing the demonstrations.12

What is new about the ACO concept and proposals?While the notion of accountability is not new, the locus of accountability has changed. “Accountability” became

a key word and critical part of the managed competition approach adopted in President Clinton’s Health Security Act, in which health maintenance organizations (HMOs) were dubbed “accountable health plans.”13 Developers of the ACO concept also emphasize accountability, but focus directly on health care providers and the delivery system instead of insurers and HMOs. The focus on local providers and delivery systems stems from a desire to address a number of continuing, frequent problems, including absence of financial incentives to reduce cost and improve quality and resultant problems, such as uncoordinated care and unwarranted geographic variation in practice patterns and health spending. The new approach, then, emphasizes accountability at the level of actual care delivery.

Second, the ACO concept envisions direct contracting with provider organizations without the reliance on a health plan intermediary and thus is distinct and separate from the contracting that occurs in the Medicare

Advantage program, which presumably would continue in parallel. Actually, in the BBA of 1997, PSOs were created to facilitate Medicare engaging in financial risk contracting directly with provider organizations. However, only a few PSOs have developed and participated in the program in the decade that this option has been available. As discussed later, current ACO proposals do not envision the degree of provider risk assumption that subjected PSOs to state insurance regulation or the BBA-enabled alternative. Nevertheless, to the extent that some ACO proposals would involve providers taking financial risk, thereby raising concerns about solvency, and would employ even mild limitations or incentives to channel beneficiaries to ACO providers, the program might again have to address complex insurance regulation issues that affected the PSO effort.14

Third, the ACO concept and current proposals potentially allow great flexibility in both the types of organizations that would qualify to serve as an ACO and the available provider payment methods. Some think this degree of flexibility differs from previous reform approaches that emphasized particular types of insurance or provider organization—HMOs or IDSs—or one approach to provider payment—full capitation, as in the PSO program. The degree of flexibility in the ACO concept and in some proposals is recognition of the substantial variation in local health care markets, as well as in provider organizations and their willingness and ability to accept nonstandard, FFS payments. The increased flexibility presumably would provide opportunities for virtually all physicians and hospitals to participate and would “let the market work,” in the sense that local market conditions and dynamics would ultimately determine which ACO organizational model and supportive payment approach prevailed in any particular area.

Figure 1. Possible ACO Configurations, Comprised of Different Provider Organizations in Local and Regional Geographic Areas

Tertiary or Quaternary Care Facility and Associated Specialty Physicians*

ACO Model 1 ACO Model 2 ACO Model 3 ACO Model 4

Independent Practice Association

(IPA) or

Primary Care Physician Groups

Specialty Groups

Multispecialty Group

Hospital

Hospital

Hospital Medical Staff Organization

(MSO) or

Physician-Hospital Organization (PHO)

Organized Delivery System

*Hospital

*Employed and Affiliated Physicians

*Possibly Other Providers, like

Post-Acute Care

*Most care provided by single ACO, but some care will be delivered by other ACOs or regional referral centers like tertiary or quaternary hospitals and their associated specialists, unless a strict beneficiary lock-in is utilized.

Timely Analysis of Immediate Health Policy Issues 4

Key ACO program featuresAlthough various authors and legislative proposals have described the broad outlines of the ACO concept,15 there are many program options and design features that are being actively discussed and debated. Decisions about these ACO program options and features would substantially affect the nature and contours of the ACO program; its implementation, including its scale, pace, challenges, and potentially necessary supports; and short and long-term outcomes with respect to cost reduction and quality improvement. Here we discuss five key issues to watch as ACO program proposals unfold.

Specific ACO definition and qualifying criteria

Legislative proposals in the House and Senate16 both define ACOs quite broadly, but seem to leave important aspects of the ACO concept somewhat unclear or reflect different perspectives on some key issues, including how much of the decisions should be left to the Secretary of HHS. Program design decision issues include which type of provider organization can lead an ACO, in particular whether it must be physician led; what other types of provider organizations may or must be included; what specific ACO qualifying criteria should govern participation; and whether PCMHs can lead or be part of an ACO.

Some believe that physician-centered organizations should lead ACOs because the resources that flow from the decisions physicians make with patients account for a major portion of overall health care costs, regardless of where the care actually takes place. Most existing physician practices, which are solo or small, single specialty groups would not possess the three essential ACO characteristics described above.17 MedPAC and others have suggested that IPAs are an organizational model that would permit even small physician practices to come together to form organizations fulfilling these criteria. Some hold that if a MSG- or IPA-based ACO did not include a hospital, these

physician-based organizations could still be held accountable for the quality and costs associated with hospitalization.

Consistent with the call for flexibility, hospitals or hospital systems (ODSs or IDSs) might also be allowed to lead an ACO. In many communities, hospitals employ a large portion of the physician workforce and they may be more likely to provide capital and management skills that ACOs would require to produce the kind of system redesign needed to methodically improve quality and reduce wasteful care in accord with a spending budget.

Indeed, to address the problem of care fragmentation, some think that local hospitals must be included in an ACO. However, others think that the relationship between physicians and hospitals is becoming so severely strained18 that perhaps we should allow separate outpatient and inpatient ACOs to develop and not force a marriage between feuding partners. While the latter approach might defeat one of the primary purposes of ACOs—accountability for the full continuum of care—it may be more feasible in the short term and potentially allow separate ACOs to come together in the future.19

Similarly, some would want other provider types, such as post acute care facilities and ambulatory surgery centers, to be part of broad ACOs. In contrast, others would not require their inclusion but would want to hold the ACO accountable for the care—and costs—provided across the range of services beneficiaries might need.

The ACO definition and accompanying qualifying criteria delineated in final legislation or demonstration guidance would strongly influence, if not actually determine, what types of organizations would lead or participate in an ACO and how they would have to be legally structured. For example, if an ACO were defined as a physician-led organization and the minimum number of physicians needed set at 200 or more, as in the PGP demonstration, only a relatively small number of existing physician groups,

mostly MSGs, would be able to meet the criteria. Smaller groups would either have to merge or, more likely, would have to form an IPA to participate. Yet, again, the current interest in ACOs arose from a desire to permit even virtual organizations of physicians working in close proximity and serving the same patients to become ACOs and thus permit looser organizations to constitute eligible ACOs.

Some recommend that even very small physician groups, such as those with three to five physicians, should be allowed to serve as ACOs; the Senate Finance Committee Chairman’s Mark also adopts this view.20 However, this approach raises concerns about small practices’ ability to fulfill the three key ACO characteristics described in the introduction and would create a much greater administrative burden for the Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) than a program relying on a smaller number of larger physician groups, IPAs, or provider organizations.

Indeed, it is not clear how the expectations for an ACO with a few physicians differ conceptually from a PCMH, and to what extent ACOs and PCMH programs complement or conflict with each other. The PCMH is an enhanced primary care practice model that provides comprehensive and timely care with appropriate reimbursement, emphasizing the central role of teamwork by a group of health professionals and more active engagement by those receiving care. The PCMH concept not only emphasizes enhanced primary care but also incorporates the ideas of provider payment and delivery system reforms, including primary care providers’ voluntary acceptance of accountability for the quality of care provided to their patients.21 Some believe that ACOs and PCMHs are complementary innovations and discuss ways they could be mutually beneficial and reinforcing.22, 23

Voluntary or mandatory provider participation

The House bill proposes a voluntary ACO provider program24 and MedPAC

Timely Analysis of Immediate Health Policy Issues 5

describes this approach as well.25 That is, an existing provider organization or new configurations of them (see figure 1 and table 1) would have to indicate proactively a desire to participate. If the traditional Medicare program adopts policies that strictly limit provider payment increases, physicians (with or without hospital partners) might want to opt out of the payment constrained FFS program by selecting the alternative ACO pathway that offers them the potential of both expanding their patient base and achieving financial rewards based on their own actual performance. Another reason physicians might voluntarily want to become an ACO is that some physicians do not like the incentives inherent in standard FFS payments and would like to be rewarded for achieving high standards on quality measurement and prudent management of health resources, which should include building stronger partnerships with patients. In short, physicians and other providers might be both pushed and pulled into an ACO program offered by the nation’s largest and most important payer—Medicare.

A voluntary provider program has several potential strengths. First, provider organizations that are able to meet the accountability tests would choose to participate, increasing the likelihood of initial ACO success and providing models for others to emulate. Second, a narrower, voluntary participation program would require fewer resources to administer and oversee initially.

However, relying on voluntary participation might result in relatively little uptake, as occurred with the PSO program. An initiative that is small in scale and involving a unique set of providers might not be particularly relevant to the challenge of fundamentally restructuring payment and practice across the country. In addition, only organizations that feel confident they would earn bonuses might choose to participate, raising concerns that a voluntary ACO program

overall would not generate savings for Medicare.26

Alternatively, in a mandatory provider program, physicians and hospitals would be assigned to a virtual ACO based on analysis of claims data; currently, provider organizations and professionals generally do not know how frequently their patients are flowing to each other’s practices and institutions and may not perceive themselves as having a common interest in caring for these patients. Plausibly, their assignment into the same virtual organization would provide them with this key information and a reason to develop their relationships, a culture of collective responsibility, and an effective governance structure.

Accordingly, there are several positive attributes of a mandatory ACO program. First, it can be much more widely applied than a voluntary program because it should engage most physicians, hospitals, and perhaps other key providers that serve Medicare beneficiaries and would provide them a reason to work together. Because of its much broader application, a mandatory program could result in greater Medicare savings27—but only if the selected payment model in fact succeeds in achieving spending reductions.

On the other hand, a broad program of assigning beneficiaries, physicians, and other providers to statistically determined ACOs would be challenging to administer. In addition, some providers would be reluctant or unprepared to alter their practice patterns to reduce cost and improve quality. Merely providing them a mild financial incentive to change their practice patterns would not guarantee that they would actually change. In addition, the physicians assigned to the ACO would need to develop a common vision of how to achieve their organizational objectives and would have to implement a functional governance structure. Some doubt that these ACO prerequisites would be accomplished in many cases. Indeed,

imposing a requirement that key health care providers participate together in an ACO might only exacerbate conflicts between health care organizations and professionals that have developed over the years, such as those between physicians and hospitals and between primary care physicians and specialists.

How beneficiaries participate in ACOs

Beneficiaries’ reactions to the ACO concept will also be important, because their perceptions would affect whether they will ultimately select ACOs if given an opportunity or whether they will support or oppose them in other ways, such as a through political activity; further, their responses could affect providers’ ability to improve their cost and quality performance. For example, if beneficiaries believe that ACOs are essentially tightly managed “HMOs in drag” that are going to restrict their choices, undermine the doctor-patient relationship, and result in cheaper but lower-quality care, the concept will be met with skepticism, if not overt opposition. On the other hand, if ACOs are viewed as a way to make the health care system easier to navigate and to improve the quality of care, to provide more for their health care dollars, and to put critical health care decisions in the hands of local doctors, hospitals, and the communities and patients they serve, the concept is likely to be more positively received. Whether and how CMS and providers communicate with beneficiaries about these ACO-related issues will influence their response to the innovation, as will two important ACO program features: (1) whether they are assigned to an ACO or, alternatively, are allowed to select participation in an ACO; and (2) whether and to what degree their access to care outside an ACO is restricted in any way.

In some ACO proposals, beneficiaries would be assigned to an ACO based on where claims analysis shows they go for their care; adopting the PGP demonstration approach, they might not even have to be informed of this

Timely Analysis of Immediate Health Policy Issues 6

assignment because their freedom of provider choice would not be restricted in any way. In this case, ACO assignment is coupled with a “no lock-in” feature. Although providers would be managing their care, beneficiaries would not necessarily even know it. Indeed, if beneficiaries’ care patterns change from one year to the next, their ACO assignments would likely change accordingly. There is a slight difference on this issue between the House Tri-Committee’s and Senate Finance Committee’s proposals, with both proposing beneficiary assignment but the House requiring that beneficiaries must be informed of that assignment and the Senate not stipulating that beneficiaries have to be informed.

Beneficiaries may view claims-based assignment and no lock-in positively, because it does not interfere with their choices or existing doctor-patient relationships; further, these features would simplify the administration of an ACO program. On the other hand, if beneficiaries indirectly and retrospectively learn that their provider had an incentive to reduce cost and improve quality, it might undermine trust in their physicians, as some contend that HMOs and managed care potentially does.28 In addition, this no lock-in feature might negatively affect ACOs’ interest in actually managing patients’ care and their ability to actually do so, making it harder to determine which patients and care management processes to focus on to achieve cost and quality targets.

An alternative is to require beneficiaries to affirmatively select an ACO if one exists in the community, much as patients select an HMO network, and to commit to seeking their care from ACO providers for some set time. This option would require more extensive efforts to help beneficiaries and consumers understand what ACOs are and the respective roles and responsibilities that pertain. The mere process of facilitating beneficiary selection of ACOs would be administratively much more complex than a statistically based assignment.

This approach might invoke the need for additional regulatory oversight if ACOs wanted to use techniques to manage care similar to those used by HMOs and the rare PSOs in the Medicare Advantage program.

Because of the concern that a true lock-in would discourage beneficiary participation in what would likely be restricted ACO provider networks, variants of what might be called a soft lock-in have been suggested for ACOs where beneficiaries make an affirmative decision to associate with a particular ACO. A soft lock-in might involve financial incentives, such as differential cost sharing, to encourage beneficiaries to seek care mostly from the ACO they have selected, an approach used in preferred provider organizations and point-of-service plans. A soft lock-in might even be as simple as a good faith social contract between beneficiaries and the ACO, outlining the parties’ responsibilities to each other but otherwise not restricting freedom of choice.

Provider payment methods and financial incentives

While a number of payment models to support ACOs are possible, two very different types of ACO payment methods are included in the current House legislative proposals for testing: a shared savings program (SSP) and partial capitation, based on what some call population-based payment (PBP).29

The basic SSP concept is fairly straightforward and illustrated in figure 2. The FFS system remains intact, so providers continue to be paid on that basis. However, Medicare calculates and sets the expected total expenditures for the patients cared for by the ACO while measuring and assessing the quality of care. If the ACO provides the care its patients need for less than expected and the quality standards are met, the ACO is rewarded with a portion of the savings as a bonus. A variant of the SSP is that some portion of billed for FFS payments are withheld and only returned if the ACO provides the care its patients need for less than expected.30

Figure 2. Shared Saving Program (SSP)

2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

High Spending Area

Projected Spending

Low Spending Area

ACO Program Launch

Actual Spending

Actual Spending

Actual Spending

Savings

Savings*

Savings

Hea

lth C

are

Sp

end

ing

*How any savings would be shared (e.g., 80/20, 50/50, 40/60) by payers and providers has yet to be determined.

Timely Analysis of Immediate Health Policy Issues 7

A critical issue with the SSP payment method is how to calculate and set the expected total expenditures for patients cared for by the ACO. While the PGP demonstration used a control group as the source of expected expenditures, setting up a control group for every ACO would not be administratively feasible, particularly for a large-scale program. As an alternative, MedPAC proposes determining expected total costs and setting benchmarks based on historical spending over a three-year period, adjusted for patient case mix. Yet, even here, there are options that vary on two dimensions: (1) use of local, regional, or national spending; and (2) a focus on base spending, the rate of spending growth, or some combination of the two. Different configurations for setting spending targets would importantly determine the likelihood that any particular ACO would in fact achieve bonuses based on the success of their spending management.31