1 Diagnosis: history · 1 Fundamental principles of patient management • Diagnosis ex-juvantibus:...

Transcript of 1 Diagnosis: history · 1 Fundamental principles of patient management • Diagnosis ex-juvantibus:...

�

It is better to know what kind of patient has the disease than what kind of disease the patient has.

Sir William Osler

Introduction

Diagnosis means ‘through knowledge’ and entails ac-quisition of data about the patient and their complaint using the senses:

• observing • hearing • touching • sometimes smelling (Fig 1.1).

The purpose of making a diagnosis is to be able to offer the most:

• effective and safe treatment • accurate prognostication.

Diagnosis is made by the clinical examination, which comprises the:

• history (anamnesis) – this offers the diagnosis in about 80% of cases

• physical examination • supplemented in some cases by investigations.

Each is based on a thorough, methodical routine. Diagno-sis most importantly involves a careful history; the patient will often deliver the diagnosis from the history, though the findings from examination and investigations can be helpful. To state the obvious, it is difficult to diagnose a condition that is unknown to the diagnostician; thus ex-tensive reading of recent literature, clinical experience and discussion with colleagues is continually needed, as well as an enquiring mind. Continuing education is essential.

There are many types of diagnosis (Box 1.1), including:

• Clinical diagnosis: made from the history and exami-nation.

• Pathological diagnosis: provided from the pathology results.

• Direct diagnosis: made by observing pathognomonic features. This is occasionally possible, for example in dentinogenesis imperfecta where the abnormally translucent brownish teeth are characteristic.

• Provisional (working) diagnosis: the more usually made diagnosis. This is an initial diagnosis from which further investigations can be planned.

• Deductive diagnosis: made after due consideration of all facts from the history, examination and investigations.

• Differential diagnosis: the process of making a diag-nosis by considering the similarities and differences between similar conditions.

• Diagnosis by exclusion: identification of a disease by excluding all other possible causes.

s0010s0010

p0010p0010

u0010u0010

p0190p0190

u0020u0020

p0200p0200

u0030u0030

p0260p0260

p0020p0020

u0040u0040

1 Diagnosis: history

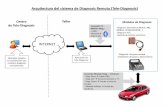

Fig. 1.1 The senses in diagnosis

f0010f0010

Listen HistorySpeech

AppearanceBehaviour

IndurationTemperature

Malodour

Observe

Touch

Smell

Listen HistorySpeech

AppearanceBehaviour

IndurationTemperature

Malodour

Observe

Touch

Smell

Fundamental principles of patient management1

�

• Diagnosis ex-juvantibus: made on the results of re-sponse to treatment. For example, the pain of trigemi-nal neuralgia may be atypical, and the diagnosis can sometimes be confirmed only by a positive response to the drug carbamazepine.

• Provocative diagnosis: the induction of a condition in order to establish a diagnosis. This is rarely needed, except in possible drug reactions or allergies, when the patient may need to be re-exposed to the poten-tially culpable substance, but this should always be carried out where appropriate medical support and resuscitation are available.

History taking

The first contact with the patient is crucial to success and there should be a courteous approach to the pa-tient with a professional introduction and every effort to establish communication, rapport and trust, and make the patient feel the focus of the clinician’s inter-est. History taking is part of the initial communication between the dentist and patient. It is important to adopt a professional appearance and manner, and in-troduce oneself clearly and courteously. The patient will know if you care, well before they care if you know.

The clinician should encourage the patient to tell the story in their own words, and use methodical question-ing to elucidate further details.

Perhaps not surprisingly, many patients are appre-hensive when confronted by a clinician, and therefore they may be easily disturbed if, for example, the clinician appears indifferent or unsympathetic. This can result in barriers to effective communication, which will simply hinder the clinician.

Due cognizance must also always be taken of the age, cultural background, understanding and intelligence of the patient when taking the history. It is the clinician’s

responsibility to elicit an accurate history; if that neces-sitates finding an interpreter, for example, then the clini-cian must arrange this.

The history is best given in the patient’s own words, though the clinician often needs to guide the patient, and may use protocols to ensure collection of all relevant points.

It is important to cover the following areas:

• general information (name, date of birth, gender, eth-nic origin, place of residence, occupation)

• presenting complaint • history of the present complaint • past medical history • dental history • family history • social and cultural history • patient expectations.

By the end of the history, the clinician should have an idea of the patient’s concerns, have assessed the patient’s current problems and also have drawn up a provisional or differential diagnosis.

Presenting complaintThe history taking commences by identifying the cur-rent complaint(s), e.g. ‘sore mouth’. The ‘history of the present complaint’ is then taken.

History of the present complaintThis should cover aspects relevant to the particular main complaint, such as:

• date of onset • duration • location(s) • aggravating and relieving factors • investigations thus far • treatment already received.

‘Leading questions’ (i.e. those which suggest the answer) should be avoided. ‘Open questions’, which do not sug-gest an answer, are preferred. The history should be directed by the complaint. Then a series of relevant ques-tions should elicit the ‘past or relevant medical history’.

Past or relevant medical historyThe medical history should be taken to elicit all matters relevant to the:

• diagnosis • treatment • prognosis.

s0020s0020

p0030p0030

p0040p0040

p0050p0050

p0060p0060

p0070p0070

p0080p0080

u0050u0050

p0210p0210

s0030s0030

p0090p0090

s0040s0040

p0100p0100

u0060u0060

p0110p0110

s0050s0050

p0120p0120

u0070u0070

ä Box 1.1

Types of diagnosis

• Clinical diagnosis • Diagnosis ex-juvantibus • Differential diagnosis • Pathological diagnosis • Direct diagnosis • Provisional (working) diagnosis • Deductive diagnosis • Diagnosis by exclusion • Provocative diagnosis: induction of a condition to

establish diagnosis

b0010b0010

Diagnosis: history 1

�

As a double check on the verbal history, the use of pre-printed, standardized, self-administered questionnaires is helpful, and may encourage more truthful responses to sensitive questions.

The history should uncover, for example, medical history relevant to:

• Previous episodes of similar or related complaints. • Other complaints that may be relevant. For example,

in patients with mucosal disorders, it is important to ascertain whether there have been lesions affecting other mucosae (ocular or anogenital) or skin.

Important to include are:

• General symptoms, such as fever or weight loss. • Relevant symptoms related to body systems, such as: • nervous system (e.g. sensory loss) • respiratory system (e.g. cough) • gastrointestinal disorders that may be associated

with oral ulcers and other lesions • skin lesions (solitary or rashes), itch or discoloura-

tions, which are common symptoms of skin disease, and there are sometimes oral lesions

• ocular problems or visual disturbance • anogenital lesions, such as ulcers or warts • psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety, depression

and eating disorders, and drug abuse are relevant to orofacial conditions.

• Medical or surgical consultations, investigations and treatments, including radiotherapy.

• Current prescribed drugs (including self-medications and alternative medicines), since these may cause oral complaints or influence management.

• Complementary medicine. • Allergies. • Previous illnesses. • Hospitalizations and previous consultations. • Operations. • Anesthetics. • Specific medical problems that may influence opera-

tive procedures, particularly: • bleeding tendency • corticosteroid therapy • diabetes • cardiac problems • endocarditis risk.

Patients may also carry formal warnings of certain con-ditions relevant to dental care. These may be written cards, smart cards, bracelets or necklaces. Some may bring quite precise written information (Fig 1.2).

The medical history of dental patients should be di-rected to elicit any relevant systemic disease. For exam-ple, this may be achieved by an ABC:

• Anaemia: a reduction in haemoglobin level below the normal for age and sex. It can:

• be a contraindication to general anaesthesia

• cause oral complications (i.e. candidiasis, sore mouth, burning tongue, glossitis, ulcers, angular stomatitis).

• Bleeding tendency: a hazard to any surgical procedure, including some injections, and a contraindication to aspirin and some other non-steroidal anti-inflamma-tory drugs (NSAIDs).

• Cardiorespiratory disease: this may be a contraindica-tion to general anaesthesia. Patients with various car-diac lesions are predisposed to develop endocarditis, which may be precipitated as a consequence of the bacteraemia associated with some forms of dental treatment. Cardiac patients may need antimicrobial cover to prevent infective endocarditis or may have a bleeding tendency because of anticoagulants.

• Drug use, allergies and abuse: these may cause orofa-cial lesions or give an indication about underlying pa-thology, or may influence dental procedures or drug use. Drug allergies are a contraindication to the use of the responsible or related drugs. Drug abuse may give rise to behavioural problems and a risk of cross-infec-tion. Corticosteroids absorbed systemically produce adrenocortical suppression. Such patients may not re-spond adequately to the stress of trauma, operation or infection, and stress may produce adrenal crisis and collapse.

• Endocrine disease. • Diabetes may cause: – the danger of hypoglycaemia if meals are inter-

fered with – oral complications such as sialosis, dry mouth

and periodontal breakdown. • Hyperparathyroidism may cause: – jaw radiolucencies/rarefaction – loss of lamina dura – giant cell granulomas (central) – hypercalcaemia. • Fits and faints: epilepsy and other causes of uncon-

sciousness should be elicited before embarking on any procedures. Oral lesions may be seen.

• Gastrointestinal disorders: are relevant mainly be-cause of possible vomiting with general anaesthesia, and possible oral manifestations.

• Hospital admissions, attendances and operations: this information often helps fill in gaps in the medical his-tory, and may be relevant if, for example, the patient has had a previous halothane anaesthetic or has had radiotherapy. Surgery in the absence of any serious postoperative haemorrhage also suggests the absence of any inherited bleeding tendency.

• Infections: the possibility of transmission of infection to patients or staff is ever present:

• blood-borne infections – hepatitis viruses B and C, and HIV are the main agents of concern

• respiratory infections – current or very recent respi-ratory infections, particularly tuberculosis, may be transmissible and a contraindication to general an-aesthesia

p0220p0220

p0130p0130

u0080u0080

p0230p0230

u0090u0090

p0240p0240

p0140p0140

u0100u0100

Fundamental principles of patient management1

�

• sexually transmitted infections – imprecise diagno-sis or empirical treatment serves only to spread these infections, as contact tracing is normally un-dertaken only on proven cases of sexually transmit-ted (venereal) disease.

• Jaundice and liver disease: these are important because of the associated bleeding tendency, drug intolerance and possible viral hepatitis and oral carcinoma.

• Kidney disease: this may cause a bleeding tendency and impaired drug excretion. The other main prob-lems are in relation to the immunosuppression cre-ated following a kidney transplant, liability to neoplasia, and gingival swelling from ciclosporin.

• Likelihood of pregnancy: because of the danger of abortion or teratogenicity, it is important during pregnancy, particularly the first trimester, to avoid or minimize exposure to drugs, radiography and infec-tions. Pregnancy can influence some conditions such as aphthae pyogenic granulations and Behçet syn-drome, and may produce gingivitis or epulides.

• Malignant disease, including those on radiotherapy or chemotherapy (where oral lesions may occur): ma-lignant disease may underlie some oral complaints, such as pain or sensory changes and can result in sig-nificant morbidity and even mortality.

• Prosthesis and transplant patients: patients after transplants may be at risk from infection, neoplasms and iatrogenic problems, such as bleeding, gingival swelling or graft-versus-host disease. Patients with transplants are also liable to present a number of com-plications to dental treatment – in particular the need for a corticosteroid cover, a liability to infection and a bleeding tendency. There is no good evidence for in-fection of prosthetic joints arising from oral sepsis. However, if the orthopaedic surgeon wishes an anti-microbial cover, the dentist must consider the medi-colegal implications.

The complications of infection of ventriculo-atrial valves are so serious that, although as in the case of prosthetic

p0150p0150

CONDITION

Blood pressure COSAARPLAVIXBEZALIP MONO

211

1

1

11

5075

400

ONCE DAILYONCE DAILYONCE DAILY

Losarton potassiumClopidogrel hydogen sulpt.BezafibrateLactose povidoneSodium lauryl sulphateHydroxypropylMethylcelluloseColloidal silicon dioxideMagnesium stearatePolymethecrylic acid eatersPolyethylene glycol. talcTitaniym dioxide (E171)Polysorbate 80Sodium dilate dihydratePlant stanolMaize starch stearic acid

Lactose, maize starchand magnesium stearatePropranolol hydrochloridePh eur and glycerolZopicloneLactose, maize starchMagnesium stearateColloidal silicon dioxideSodium starch glycol-ate and tartrazine lakeHyoscine butytoromideMedeverine hydochloride

For cholesterol

For back pain

Anxiety

For tremorSTOPPED

STOPPED

SleepSleep

For IBS when requiredCOLOFACBUSCOPAN

BENECOL 2g500

207510

10

7.5ONCE A NIGHT

3 TIMES DAILY2 101 Before a meal

ONCE A NIGHT

ONCE DAILY

ONCE DAILY

ONCE DAILYONCE DAILYONCE DAILY

3 TIMES DAILY

5

Yogurt

PARACETAMOL

OXAZEPAMASPIRINOMERPROZOLE

DIAZEPAMZIMOVANE

INDERAL

For IBS when required

(From 19-03-04)

DESCRIPTIONNO.

OF PILLSMG PERIOD CONTENTS

ONPrescrtn.

Fig. 1.2 Medical history sheet given by a fastidious patient

f0020f0020

Diagnosis: history 1

�

joints there is little evidence for an oral source, it may be reasonable to give an antimicrobial cover, if the respon-sible neurosurgeon so advises. Patients with pacemak-ers may be in danger in relation to the use of equipment, which can interfere with their pacemaker, such as dia-thermy and electrosurgery.

• Other relevant conditions: every condition which is elic-ited from the medical history should be checked for rel-evance, but the following can be highly relevant:

• Down syndrome – there are many oral problems and cervical spine involvement may predispose to spinal cord damage during general anaesthesia

• glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency is a contraindication to some drugs

• hereditary angioedema – any dental trauma may result in oedema and a hazard to the airway

• malignant hyperthermia (malignant hyperpy-rexia) – various general anaesthetics and other agents may be contraindicated

• porphyria – intravenous barbiturates, metronida-zole and other agents may be contraindicated

• rheumatoid arthritis – cervical spine involvement may predispose to spinal cord damage if the neck is

flexed during general anaesthesia; Sjögren syn-drome is a common complication

• suxamethonium sensitivity – suxamethonium is contraindicated.

Dental historyThe dental history will give an idea of the:

• regularity of attendance for dental care • attitude to dental professionals and to treatment • recent relevant dental problems • recent restorative treatment.

Family historyThis may reveal hereditary problems, such as amelogen-esis imperfecta, haemophilia or hereditary angioedema, and familial conditions, such as recurrent aphthous stomatitis or diabetes. Some diseases are more prevalent in certain ethnic groups, e.g. pemphigus in Jews; Behçet’s disease in people from the Mediterranean area.

u0110u0110

s0060s0060

p0160p0160

u0120u0120

s0070s0070

p0170p0170

ä Box 1.2

Systematic recording of relevant medical history

System* Specific problems No Yes

CVS Heart disease, hypertension, angina, syncopeCardiac surgery, rheumatic fever, choreaBleeding disorder, anticoagulants, anaemia

RS Asthma, bronchitis, TB, other chest disease, smoker

GU Renal, urinary tract or sexually transmitted diseasePregnancy, menstrual problems

GI/Liver Coeliac disease, Crohn’s diseaseHepatitis, other liver disease, jaundice

CNS CVA, multiple sclerosis, other neurological diseasePsychiatric problems, drug or alcohol abuseSight or hearing problems

LMS Bone, muscle or joint disease

Endocrine Diabetes, thyroid, other endocrine disease

Allergy Allergies – e.g. penicillin, aspirin, plaster

Drugs Recent or current drugs/medical treatmentCorticosteroids, anticoagulants

Others Previous operations, general anaesthesia (GA) or serious illnessOther conditions (including congenital anomalies)Family medical historyBorn, residence or travel abroadPets

*CVS: cardiovascular; RS: respiratory; GU: genitourinary; GI: gastrointestinal; CNS: central nervous system; LMS: locomotor system.

b0020b0020

Fundamental principles of patient management1

�

Social and cultural historyThe social history may reveal:

• whether the patient has family or a partner and the degree of support that can be anticipated

• information about the patient’s residence, which can suggest the socioeconomic circumstances of the patient

• information about contacts with pets and other animals, which may be relevant to some infectious diseases, such as cat-scratch disease or toxoplasmosis

• whether the patient has traveled overseas, which may be relevant to some infectious diseases, such as tropi-cal diseases and deep mycoses

• the patient’s sexual history, which may be relevant to some infectious diseases, such as human immunodefi-ciency virus (HIV), herpes simplex virus (HSV), papil-lomavirus (HPV) and hepatitis viruses A (HAV), B (HBV) and C (HCV)

• any occupational problems, which may be relevant to some disease, and access to care

• relevant habits (tobacco, alcohol, betel and recrea-tional drug use) – tobacco use underlies several oral diseases, including periodontal disease and cancer

• relevant hobbies, such as swimming that may cause tooth erosion or scuba diving that may underlie tem-poromandibular pain

• information about the patient’s diet – dietary fads may lead, for example, to vitamin deficiencies and glossitis or angular cheilitis (as in vitamin B12 defi-ciency in vegans)

• information about stress.

Standardized forms will help with the recording of data, the relevance of which can sometimes be surprising (Box. 1.2).

Patient expectations can only be assessed by polite enquiry. Each patient is an individual with their own specific thoughts and beliefs.

Further readingAbraham-Inpijn L. 2000 Local anesthesia and patients presenting with

medical pathologies; the use of anamnesis in the prevention of medical complications in the dental office. Rev Belge Med Dent ��(1):�2–�9

Abraham-Inpijn L., Abraham E.A., Backman N. et al 2000 Is het nog wel veilig in de tandartsstoel? Nederlands Tandartsenblad ��:1�–1�

Ferlito A., Boccato P., Shaha A.R,. et al 2001 The art of diagnosis in head and neck tumors. Acta Otolaryngol 121:�2�–�2�

Ragonesi M., Ivaldi C. 200� Anaesthesiological risk assessment in young/adult and elderly dental patients. Gerodontology 22(2): 109–111

Scully C., Kalantzis A. 200� Oxford handbook of dental patient care, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Scully C., Wilson N. 200� Culturally sensitive oral health care. Quintessence Publishers, London

s0080s0080

p0180p0180

u0130u0130

p0250p0250

s0090s0090

�

The patient will know if you care, well before they care if you know.

Anonymous

Introduction

The clinical examination of the patient should start as the patient enters the clinic and is greeted by the clinician. The history and clinical examination are designed to put the clinician in a position to make a provisional diagnosis, or a differential diagnosis. Special tests or investigations may be required to confirm or refine this diagnosis or elicit other conditions. Physical disabilities, such as those affect-ing gait, and learning disability are often immediately evident as the patient is first seen, and blindness, deafness or speech and language disorders may be obvious. You should also be able to assess the patient’s mood and gen-eral wellbeing but, if in any doubt, ask for advice. Other disorders, such as mental problems, may become appar-ent at any stage. The patient should be carefully observed and listened to during history taking and examination; speech and language can offer a great deal of information about the medical and mental state. As a general rule, if you think a patient looks ill, they probably are.

Always remember that the patient has the right to refuse all or part of the examination, investigations or treatment. A patient has the right under common law to give or with-hold consent to medical examination or treatment. This is one of the basic principles of healthcare. Patients are enti-tled to receive sufficient information in a way they can understand about the proposed investigations or treat-ments, the possible alternatives and any substantial risk or risks, which may be special in kind or magnitude or spe-cial to the patient, so that they can make a balanced judg-ment (UK Health Department, 19.2.99. HSC 1999/031),

There may be cultural sensitivities but, in any case, no examination should be carried out in the absence of a chap-erone – preferably of the opposite sex to the practitioner.

General examination

Medical problems may manifest in the fully clothed patient with abnormal appearance or behaviour, pupil size, con-scious level, movements, posture, breathing, speech, facial

colour, sweating or wasting. General examination may sometimes include the recording of body weight and the ‘vital signs’ of conscious state, temperature, pulse, blood pressure and respiration. The dentist must be prepared to interpret the more common and significant changes.

Vital signs • The conscious state. • The temperature: the temperature is traditionally

taken with a thermometer, but temperature-sensitive strips and sensors are available. Leave the thermom-eter in place for at least 3 minutes. The normal body temperatures are: oral 36.6°C; rectal or ear (tympanic membrane) 37.4°C; and axillary 36.5°C. Body temper-ature is usually slightly higher in the evenings. In most adults, an oral temperature above 37.8°C or a rectal or ear temperature above 38.3°C is considered a fever. A child has a fever when ear temperature is 38°C or higher.

• The pulse: this can be measured manually or auto-matically (Fig. 2.1). The pulse can be recorded from any artery, but in particular from the following sites:

• the radial artery, on the thumb side of the flexor surface of the wrist

• the carotid artery, just anterior to the mid-third of the sternomastoid muscle

• the superficial temporal artery, just in front of the ear. • Pulse rates at rest in health are approximately as follows: • infants, 140 beats/minute • adults, 60–80 beats/minute.

p0190p0190

s0010s0010

p0010p0010

p0020p0020

p0030p0030

s0020s0020

p0040p0040

s0030s0030

u0010u0010

2 Diagnosis: examination

Fig. 2.1 Pulse meter

f0010f0010

Fundamental principles of patient management1

10

• Pulse rate is increased in: • exercise • anxiety or fear • fever (pyrexia) • some cardiac disorders • hyperthyroidism and other disorders. • The rhythm should be regular; if not, ask a physician

for advice. The character and volume vary in certain disease states and require a physician’s advice.

• The blood pressure: this can be measured with a sphygmomanometer (Fig. 2.2), or one of a variety of machines. With a sphygmomanometer the procedure is as follows: seat the patient; place the sphygmoma-nometer cuff on the right upper arm, with about 3cm of skin visible at the antecubital fossa; palpate the ra-dial pulse; inflate the cuff to about 200–250mmHg or until the radial pulse is no longer palpable; deflate the cuff slowly while listening with the stethoscope over the brachial artery on the skin of the inside arm below the cuff; record the systolic pressure as the pressure when the first tapping sounds appear; deflate the cuff further until the tapping sounds be-come muffled (diastolic pressure); repeat; record the blood pressure as systolic/diastolic pressures (nor-mal values about 120/80mmHg, but these increase with age).

Other signs • Weight: weight loss is seen mainly in malnutrition,

eating disorders, cancer, HIV disease, malabsorption and tuberculosis. Obesity is usually due to excessive food intake and insufficient exercise.

• Hands: conditions, such as arthritis (mainly rheuma-toid or osteoarthritis) (Figs 2.3 and 2.4) and Raynaud’s phenomenon, which is seen in many connective tissue diseases. Disability, such as in cerebral palsy (Fig. 2.5).

s0040s0040

u0020u0020

Fig. 2.2 Sphygmomanometer

f0020f0020

Fig. 2.3 Raynaud’s syndrome in scleroderma

f0030f0030

Fig. 2.4 Heberden’s nodes of osteoarthritis

f0040f0040

Fig. 2.5 Cerebral palsy

f0050f0050

Diagnosis: examination 1

11

• Skin: lesions, such as rashes – particularly blisters (seen mainly in skin diseases, infections and drug reactions), pigmentation (seen in various ethnic groups, Addison’s disease and as a result of some drug therapy).

• Skin appendages: nail changes, such as koilonychia (spoon-shaped nails), as seen in iron deficiency anae-mia, hair changes, such as alopecia, and finger club-bing (Fig. 2.6), as seen mainly in cardiac or respiratory disorders. Nail beds may reveal the anxious nature of the nail-biting person (Fig. 2.7)

Extraoral head and neck examination

The face should be examined for lesions (Box 2.1) and features such as:

• pallor, seen mainly in the conjunctivae or skin creases in anaemia

• rash, such as the malar rash in systemic lupus ery-thematosus

• erythema, seen mainly on the face in an embarrassed patient, or fever (sweating or warm hands), and then usually indicative of infection. Malar erythema may indicate mitral valve stenosis.

Eyes should be examined for features such as:

• exophthalmos (prominent eyes), seen mainly in Graves thyrotoxicosis

• jaundice, seen mainly in the sclerae in liver disease

• redness, seen in trauma, eye diseases, or Sjögren syn-drome

• scarring, seen in trauma, infection or pemphigoid.

Inspection of the neck, looking particularly for swellings or sinuses, should be followed by careful palpation of all cervical lymph nodes and salivary and thyroid glands, searching for swelling or tenderness. The neck is best examined by observing the patient from the front, not-ing any obvious asymmetry or swelling, then standing behind the seated patient to palpate the lymph nodes. Most of the physical examination is undertaken from be-hind (Fig. 2.8). Systematically, each region needs to be examined lightly with the pulps of the fingers, trying to roll the lymph nodes against harder underlying structures:

Lymph from the superficial tissue of the head and neck generally drains first to groups of superficially placed lymph nodes, then to the deep cervical lymph nodes (Figs. 2.9–2.11 and Box 2.2).

• Parotid, mastoid and occipital lymph nodes can be palpated simultaneously using both hands.

• Superficial cervical lymph nodes are examined with lighter fingers as they can only be compressed against the softer sternomastoid muscle.

• Submental lymph nodes are examined by tipping the patient’s head forward and rolling the lymph nodes against the inner aspect of the mandible.

• Submandibular lymph nodes are examined in the same way, with the patient’s head tipped to the side which is being examined. Differentiation needs to be made between the submandibular salivary gland and submandibular lymph glands. Bimanual examina-tion with one finger in the floor of the mouth may help.

• The deep cervical lymph nodes which project anterior or posterior to the sternomastoid muscle can be pal-pated. The jugulodigastric lymph node in particular should be specifically examined, as this is the most common lymph node involved in tonsillar infections and oral cancer.

s0050s0050

p0050p0050

u0030u0030

u0040u0040

p0060p0060

p0070p0070

u0050u0050

Fig. 2.6 Clubbing

f0060f0060

Fig. 2.7 Nail biting

f0070f0070

p0130

Fundamental principles of patient management1

12

• The supraclavicular region should be examined at the same time as the rest of the neck; lymph nodes here may extend up into the posterior triangle of the neck on the scalene muscles, behind the sterno-mastoid.

• Parapharyngeal and tracheal lymph nodes can be compressed lightly against the trachea.

• Some information can be gained by the texture and nature of the lymphadenopathy.

• Tenderness and swelling should be documented. Lymph nodes that are tender may be inflammatory (lymphadenitis). Consistency should be noted. Nodes that are increasing in size and are hard, or fixed to ad-jacent tissues may be malignant.

➤ Box 2.1

The commoner descriptive terms applied to lesions

Term Meaning

Atrophy Loss of tissue with increased translucency, unless sclerosis is associated

Bullae Visible accumulations of fluid within or beneath the epithelium, >0.5cm in diameter

Cyst Closed cavity or sac (normal or abnormal) with an epithelial, endothelial or membranous lining and containing fluid or semisolid material

Ecchymosis Macular area of haemorrhage >2cm in diameter (bruise)

Erosion Loss of epithelium which usually heals without scarring; it commonly follows a blister

Erythema Redness of the mucosa produced by atrophy, inflammation, vascular congestion or increased perfusion

Exfoliation The splitting off of the epithelial keratin in scales or sheets

Fibrosis The formation of excessive fibrous tissue

Fissure Any linear gap or slit in the skin or mucosa

Gangrene Death of tissue, usually due to loss of blood supply

Haematoma A localized tumour-like collection of blood

Keloid A tough heaped-up scar that rises above the rest of the skin, is irregularly shaped and tends to enlarge progressively

Macule A circumscribed alteration in colour or texture of the mucosa

Nodule A solid mass in the mucosa or skin which can be observed as an elevation or can be palpated; it is >0.5cm in diameter

Papule A circumscribed palpable elevation <0.5cm in diameter

Petechia (pl. petechiae) A punctate haemorrhagic spot approximately 1–2mm in diameter

Plaque An elevated area of mucosa >0.5cm in diameter

Pustule A visible accumulation of free pus

Scar Replacement by fibrous tissue of another tissue that has been destroyed by injury or disease. An atrophic scar is thin and wrinkled. A hypertrophic scar is elevated; with excessive growth of fibrous tissue. A cribriform scar is perforated with multiple small pits

Sclerosis Diffuse or circumscribed induration of the submucosal and/or subcutaneous tissues

Tumour Literally a swelling. The term is used to imply enlargement of the tissues by normal or pathological material or cells that form a mass. The term should be used with care, as many patients believe it implies a malignancy with a poor prognosis

Ulcer A loss of epithelium, often with loss of the underlying tissues, produced by sloughing of necrotic tissue

Vegetation A growth of pathological tissue consisting of multiple closely set papillary masses

Vesicle Small (<0.5cm in diameter) visible accumulation of fluid within or beneath the epithelium

Wheal A transient area of mucosal or skin oedema, white, compressible and usually evanescent

b0010b0010

Diagnosis: examination 1

13

SialadenitisSalivary calculusSalivary tumourSjögren syndromeMalignancyHIV/AIDS

RubellaInfectious mononucleosisBrucellosisToxoplasmosisCytomegalovirus infectionTuberculosisLymphoreticular diseaseHIV/AIDS

LymphadenitisHIV/AIDSLymphoreticular diseaseMalignancy in lymph node

Branchial cystCarotid body tumourLaryngocele

Sternomastoid Trapezius

Fig. 2.8 Some causes of neck swelling

f0080f0080

Trapezius muscle

Preauricular

Postauricular

Suboccipital

Posterior cervical

Supraclavicular

Sternomastoid muscle

Jugulodigastric (tonsillar)

FacialSubmandibular

Submental

Jugulo-omohyoid

Masseter muscle

Fig. 2.9 Cervical lymph nodes

f0090f0090

Submandibular

Submental

Fig. 2.10 Submental and submandibular lymph nodes

f0100f0100

Jugulodigastric

Middle cervical

Submandibular

Fig. 2.11 Submandibular and deep cervical lymph nodes

f0110f0110

Fundamental principles of patient management1

14

• Both anterior and posterior cervical nodes should be examined as well as other nodes, liver and spleen if systemic disease is a possibility. Generalized lym-phadenopathy with or without enlargement of other lymphoid tissue, such as liver and spleen (hepat-osplenomegaly), suggests a systemic cause.

The temporomandibular joints (TMJ) and muscles of mastication should be examined and palpated. Although disorders that affect the TMJ often appear to be unilat-eral, the joint should not be viewed in isolation, but al-ways considered along with its opposite joint, as part of the stomatognathic system. Some practitioners palpate using a pressure algometer to standardize the force used, and undertake range-of-movement (ROM) meas-urements. The area should be examined by inspecting:

• Facial symmetry, for evidence of enlarged masseter muscles (masseteric hypertrophy) suggestive of clenching or bruxism. A bruxchecker can help confirm bruxism.

• Mandibular opening and closing paths, noting any noises or deviations.

• Mandibular opening extent, measuring the inter-in-cisal distance at maximum mouth opening.

• Lateral excursions, measuring the amount achievable. • Joint noises, by listening (a stethoscope placed over

the joint can help). • Both condyles, by palpating them, via the external au-

ditory meatus, to detect tenderness posteriorly, and by using a single finger placed over the joints in front of the ears, to detect pain, abnormal movements or clicking within the joint.

u0060u0060

➤ Box 2.2

The cervical lymph nodes and their main drainage areas

Area Draining lymph nodes

Scalp, temporal region Superficial parotid (pre-auricular)

Scalp, posterior region Occipital

Scalp, parietal region Mastoid

Ear, external Superficial cervical over upper part of sternomastoid muscle

Ear, middle Parotid

Over angle of mandible Superficial cervical over upper part of sternomastoid muscle

Medial part of frontal region, medial eyelids, skin of nose Submandibular

Lateral part of frontal region, lateral part of eyelids Parotid

Cheek Submandibular

Upper lip Submandibular

Lower lip Submental

Lower lip, lateral part Submandibular

Mandibular gingivae Submandibular

Maxillary teeth Deep cervical

Maxillary gingivae Deep cervical

Tongue tip Submental

Tongue, anterior two-thirds Submandibular, some midline cross-over of lymphatic drainage

Tongue, posterior third Deep cervical

Tongue ventrum Deep cervical

Floor of mouth Submandibular

Palate, hard Deep cervical

Palate, soft Retropharyngeal and deep cervical

Tonsil Jugulodigastric

b0020b0020

p0140

Diagnosis: examination 1

15

• Masticatory muscles on both sides, noting tenderness or hypertrophy:

• Masseters, by intraoral–extraoral compression be-tween finger and thumb. Palpate the masseter bi-manually by placing a finger of one hand intraorally and the index and middle fingers of the other hand on the cheek over the masseter over the lower man-dibular ramus.

• Temporalis, by direct palpation of the temporal re-gion and by asking the patient to clench the teeth. Palpate the insertion of the temporalis tendon in-traorally along the anterior border of the ascending mandibular ramus.

• Lateral pterygoid (lower head), by placing a little finger up behind the maxillary tuberosity (tender-ness is the ‘pterygoid sign’). Examine it indirectly by asking the patient to open the jaw against resist-ance and to move the jaw to one side while apply-ing a gentle resistance force.

• Medial pterygoid muscle, intraorally lingually to the mandibular ramus.

• The dentition and occlusion. This may require moni-toring of study models on a semi or fully adjustable articulator. Note particularly missing premolars or molars, and attrition.

• The mucosa. Note particularly occlusal lines and scal-loping of the tongue margins, which may indicate bruxism and tongue pressure.

Examine the jaws. There is a wide normal individual variation in morphology of the face. Most individuals have facial asymmetry but of a degree that cannot be regarded as abnormal. Maxillary, mandibular or zygo-matic deformities or lumps may be more reliably con-firmed by inspection from above (maxillae/zygomas) or behind (mandible). The jaws should be palpated to de-tect swelling or tenderness. Maxillary air sinuses can be examined by palpation for tenderness over the maxil-lary antrum, which may indicate sinus infection. Tran-sillumination or endoscopy can be helpful. The major salivary glands should be inspected and palpated (pa-rotids and submandibulars) for:

• symmetry • evidence of enlarged glands • evidence of salivary flow from salivary ducts • evidence of salivary pooling in the floor of mouth • saliva appearance • evidence of oral dryness (food residues; lipstick on

teeth; scarce saliva; mirror sticks to mucosa); sialome-try (salivary flow rate; see page 31).

Salivary glands are palpated in the following way:

• Parotid glands are palpated by using fingers placed over the glands in front of the ears, to detect pain or swelling. Early enlargement of the parotid gland is characterized by outward deflection of the lower

part of the ear lobe, which is best observed by look-ing at the patient from behind. This sign may allow distinction from simple obesity. Swelling of the parotid sometimes causes trismus. Swellings may affect the whole or part of a gland, or tenderness may be elicited. The parotid duct (Stensen’s duct) is most readily palpated with the jaws clenched firmly, since it runs horizontally across the upper masseter where it can be gently rolled; the duct opens at a papilla on the buccal mucosa opposite the upper molars.

• Submandibular glands are palpated bimanually be-tween fingers inside the mouth and extraorally. The submandibular gland is best palpated bimanually with a finger of one hand in the floor of the mouth lingual to the lower molar teeth, and a finger of the other hand placed over the submandibular triangle. The submandibular duct (Wharton’s duct) runs an-teromedially across the floor of the mouth to open at the side of the lingual fraenum.

Examine the cranial nerves (Table 2.1). In particular, fa-cial movement should be tested and facial sensation de-termined. Facial symmetry is best seen as the patient is talking. Movement of the mouth as the patient speaks is important, especially when they allow themselves the luxury of some emotional expression. The upper part of the face is bilaterally innervated and thus loss of wrin-kles on one-half of the forehead or absence of blinking suggests a lesion in the lower motor neurone. Examina-tion of the upper face (around the eyes and forehead) is carried out in the following way:

• If the patient is asked to close their eyes the palsy may become obvious, with the affected eyelid failing to close and the globe turning up so that only the white of the eye is showing (Bell’s sign).

• Weakness of orbicularis oculi muscles with sufficient strength to close the eye can be compared with the normal side by asking the patient to close the eyes tight and observing the degree of force required to part the eyelids.

• If the patient is asked to wrinkle the forehead, weak-ness can be detected by the difference between the two sides.

The lower face (around the mouth) is best examined by asking the patient to:

• smile • bare the teeth or purse the lips • blow out the cheeks or whistle.

The cranial nerves can be examined further:

• The corneal reflex: this depends on the integrity of the trigeminal and facial nerves, either of which if defec-tive will give a negative response. It is important to

p0080p0080

u0070u0070

u0080u0080

u0090u0090

u0100u0100

u0110u0110

p0150

p0160

p0170

p0180

Fundamental principles of patient management1

16

test facial light touch sensation in all areas but par-ticularly the corneal reflex. Lesions involving the ophthalmic division cause corneal anaesthesia, which is tested by gently touching the cornea with a wisp of cotton wool twisted to a point. Normally, this proce-dure causes a blink but, if the cornea is anaesthetic (or if there is facial palsy), no blink follows, provided that the patient does not actually see the cotton wool. If the patient complains of complete facial or hemifa-cial anaesthesia, but the corneal reflex is retained or there is apparent anaesthesia over the angle of the mandible (an area not innervated by the trigeminal nerve), then the symptoms are probably functional (non-organic).

• Taste: unilateral loss of taste associated with facial palsy indicates that the facial nerve is damaged proxi-mal to the chorda tympani nerve.

• Hearing: hyperacusis may be caused by paralysis of the stapedius muscle and this suggests the facial nerve lesion is proximal to the nerve to the stapedius.

• Lacrimation: this is tested by hooking a strip of Schirmer or litmus paper in the lower conjunctival fornix. The strip should dampen to at least 15mm in 1 minute if tear pro-duction is normal. The contralateral eye serves as a control (Schirmer’s test). Secretion is diminished in proximal le-sions of the facial nerve, such as those involving the genic-ulate ganglion or in the internal auditory meatus, or in disorders of exocrine glands, such as Sjögren syndrome.

Table 2.1Examination of cranial nerves

Cranial nerve Findings in lesions

I Olfactory Impaired sense of smell for common odours (do not use ammonia)

II Optic Visual acuity reduced using Snellen types ± ophthalmoscopy: nystagmusVisual fields by confrontation impairedPupil responses may be impaired

III Oculomotor Diplopia; strabismus; eye looks down and laterally (‘down and out’)Eye movements impairedPtosis (drooping eyelid)Pupil dilatedPupil reactions: direct reflex impaired, but consensual reflex intact

IV Trochlear Diplopia, particularly on looking downStrabismus (squint)No ptosisPupil normal and normal reactivity

V Trigeminal Reduced sensation over face ± corneal reflex impaired ± taste sensation impairedMotor power of masticatory muscles reduced, with weakness on opening jaw; jaw jerk impairedMuscle wasting

VI Abducens Diplopia (double vision)StrabismusLateral eye movements impaired to affected side

VII Facial Impaired motor power of facial muscles on smiling, blowing out cheeks, showing teeth, etc.Corneal reflex reduced ± taste sensation impaired

VIII Vestibulocochlear Impaired hearing (tuning fork at 256 Hz)Impaired balance ± nystagmus ± tinnitus

IX Glossopharyngeal Reduced gag reflexDeviation of uvulaReduced taste sensationVoice may have nasal tone

X Vagus Reduced gag reflexVoice may be impaired

XI Accessory Motor power of trapezius and sternomastoid reduced

XII Hypoglossal Motor power of tongue impaired, with abnormal speech ± fasciculation, wasting, ipsilateral deviation on protrusion

t0010

Diagnosis: examination 1

17

• Facial sensation: progressive lesions affecting the sen-sory part of the trigeminal nerve initially result in a diminishing response to light touch (cotton wool) and pin-prick (gently pricking the skin with a sterile pin or needle without drawing blood), and later there is complete anaesthesia.

Intraoral examination

Few oral diseases are life threatening, though cancer and pemphigus are obvious exceptions. Most diseases have a local cause and can be recognized fairly readily. Even those that are life threatening, such as oral cancer in particular, can be detected at an exceedingly early stage. However, even now, oral cancer is sometimes overlooked at examination, and the delay between the onset of symptoms of oral cancer and the institution of definitive treatment still often exceeds 6 months. The same applies to pemphigus.

Many systemic diseases, particularly infections and diseases of the blood, gastrointestinal tract and skin, also cause oral signs or symptoms that may constitute the main complaint, particularly, for example, in some patients with HIV, leukopenia or leukaemia.

The examination, therefore, should be conducted in a systematic fashion to ensure that all areas are included. If the patient wears any removable prostheses or appliances, these should be removed in the first instance, although it may be necessary later to replace the appliance to assess its fit, function and relationship to any lesion.

Complete visualization with a good source of light is essential. All mucosal surfaces should be examined, starting away from the location of any known lesions or the focus of complaint, and lesions recorded on a dia-gram (Fig. 2.12). The lips should first be inspected. The labial mucosa, buccal mucosa, floor of the mouth and

ventrum of the tongue, dorsal surface of the tongue, hard and soft palates, gingivae and teeth should then be examined in sequence (Box 2.3):

• Lips: features, such as cyanosis, are seen mainly in the lips in cardiac or respiratory disease; angular cheilitis is seen mainly in oral candidiasis or iron or vitamin deficiencies. Many adults have a few yellowish pinhead-sized papules in the vermilion border (particularly of the upper lip) and at the commissures; these are usually ectopic sebaceous glands (Fordyce spots), and may be numerous, especially as age advances.

• Labial mucosa normally appears moist with a fairly prominent vascular arcade. Examination is facilitated if the mouth is gently closed at this stage, so that the lips can then be everted to examine the mucosa. In the lower lip, the many minor salivary glands, which are often exuding mucus, are easily visible. The lips, therefore, feel slightly nodular and the labial arteries are readily felt.

• Cheek (buccal) mucosa is readily inspected if the mouth is held half open. The vascular pattern and minor sali-vary glands so prominent in the labial mucosa are not obvious in the buccal mucosa, but Fordyce spots may be conspicuous, particularly near the commissures and retromolar regions in adults and there may be a faint horizontal white line where the teeth meet (linea alba). Place the surface of a dental mirror against the buccal mucosa. The mirror should slide and lift off easily; if it adheres to the mucosa, then xerostomia is present.

• The floor of the mouth and the ventrum of the tongue are best examined by asking the patient to push the tongue first into the palate and then into each cheek in turn. This raises for inspection the floor of the mouth – an area where tumours may start (the coffin or grave-yard area of the mouth). Its posterior part is the most difficult area to examine well and one where lesions are most easily missed. Lingual veins are prominent and,

s0060s0060

p0090p0090

p0100p0100

p0110p0110

p0120p0120

u0120u0120

Lip

Hard palate

Soft palate

Buccal mucosa

Right Left

Tongue(dorsum)

Lateraltongue

Lateraltongue

Anteriorpillar

Posteriorpillar

Tongue(ventral)

Right Left

Vee

stibulGing

iva

Labial mucosa

Lip

Labial mucosa

Ging

iva

Vestibule

Commissure

Floor ofmouth

Fig. 2.12 Mouth chart

f0120f0120

Fundamental principles of patient management1

18

in the elderly, may be conspicuous (lingual varices). Bony lumps on the alveolar ridge lingual to the premo-lars are most often tori (torus mandibularis) – a normal variant. During this part of the examination the quan-tity and consistency of saliva should be assessed. Ex-amine for the pooling of saliva in the floor of the mouth; normally there is a pool of saliva.

• The dorsum of the tongue is best inspected by protru-sion, when it can be held with gauze. The anterior two-thirds is embryologically and anatomically dis-tinct from the posterior third, and separated by a dozen or so large circumvallate papillae. The anterior two-thirds is coated with many filiform, but relatively few fungiform papillae. Behind the circumvallate papillae, the tongue contains several large lymphoid masses (lingual tonsil) and the foliate papillae lie on

the lateral borders posteriorly. These are often mis-taken for tumours. The tongue may be fissured (scro-tal), but this is a developmental anomaly. A healthy child’s tongue is rarely coated, but a mild coating is not uncommon in healthy adults. The voluntary tongue movements and sense of taste should be for-mally tested. Abnormalities of tongue movement (neurological or muscular disease) may be obvious from dysarthria (abnormal speech) or involuntary movements, and any fibrillation or wasting should be noted. Hypoglossal palsy may lead to deviation of the tongue towards the affected side on protrusion. For-mal taste testing with salt, sweet, sour and bitter should be carried out by applying solutions of salt, sugar, dilute acetic acid and 5% citric acid to the tongue on a cotton swab or cotton bud.

➤ Box 2.3

The more commonly used tooth notations

PalmerPermanent dentition

Upper

Right Left

Lower

87654321 12345678

87654321 12345678

|

|

Deciduous dentition (anonymous classification)EDCBA ABCDEEDCBA ABCDE

||

HaderupPermanent dentition( )( )( )( )( )( )( )( ) | ( )( )( )( )( )(8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6+ + + + + + + + + + + + + + ))( )( )( )( )( )( )( )( )( )( ) | ( )( )( )(

+ +− − − − − − − − − − −

7 88 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 −− − − − −4 5 6 7 8)( )( )( )( )

Deciduous dentition( )( )( )( )( ) | ( )( )( )( )( )( )50 40 30 20 10 01 02 03 04 0550

+ + + + + + + + + +−

(( )( )( )( ) | ( )( )( )( )( )40 30 20 10 01 02 03 04 05− − − − − − − − −

UniversalPermanent dentition

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 1632 31 30 29 28

|227 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 |

Deciduous dentitionA B C D E F G H I J

T S R Q P O N M L K|

|

Fédération Dentaire Internationale (two-digit)Permanent dentition18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 | 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 2848 47 466 45 44 43 42 41 | 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38

Deciduous dentition55 54 53 52 51 61 62 63 64 6585 84 83 82 81 71 72

|| 773 74 75

b0030b0030

Diagnosis: examination 1

1�

• The palate and fauces consist of an anterior hard pal-ate and posterior soft palate, and the tonsillar area and oropharynx. The mucosa of the hard palate is firmly bound down as a mucoperiosteum (similar to the gin-givae) and with no obvious vascular arcades. Ridges (rugae) are present anteriorly on either side of the in-cisive papilla that overlies the incisive foramen. Bony lumps in the posterior centre of the vault of the hard palate are usually tori (torus palatinus). Patients may complain of a lump distal to the upper molars that they think is an unerupted tooth, but the pterygoid hamulus or tuberosity is usually responsible for this complaint. The soft palate and fauces may show a faint vascular arcade. Just posterior to the junction with the hard palate is a conglomeration of minor salivary glands. This region is often also yellowish. The palate should be inspected and movements exam-ined when the patient says ‘Aah’. Using a mirror, this also permits inspection of the posterior tongue, ton-sils, oropharynx, and can even offer a glimpse of the larynx. Glossopharyngeal palsy may lead to uvula de-viation to the contralateral side. Bifid uvula may sig-nify a submucous cleft palate.

• Gingivae in health are firm, pale pink, with a stippled surface, and have sharp gingival papillae reaching up between the adjacent teeth to the tooth contact point. Look for gingival redness, swelling, or bleeding on gently probing the gingival margin. The ‘keratinized’ attached gingivae (pale pink) is normally clearly de-marcated from the non-keratinized alveolar mucosa (vascular) that runs into the vestibule or sulcus. Bands of tissue, which may contain muscle attachments, run centrally from the labial mucosa onto the alveolar mu-cosa and from the buccal mucosa in the premolar re-gion onto the alveolar mucosa (fraenae).

• Teeth: the dentition should be checked to make sure that the expected complement of teeth is present for the patient’s age. Extra teeth (supernumerary teeth) or deficiency of teeth, partial loss (hypodontia; oligodon-tia) or complete loss (anodontia) can be features of many syndromes, but teeth are far more frequently

missing because they are unerupted, impacted or lost as a result of caries or periodontal disease. The teeth should be fully examined for signs of disease, either malformations, such as hypoplasia or abnormal col-our, or acquired disorders such as dental caries, stain-ing, erosion or abrasion or fractures. The laser fluorescence device DIAGNOdent may help caries de-tection. Apex locators, such as Propex (third genera-tion) and Raypex-4 (fourth generation), may help define root fractures. The occlusion of the teeth should also be checked; it may show attrition or may be dis-turbed, as in some jaw fractures or dislocation of the mandibular condyles.

Further readingal Kadi H., Sykes L.M., Vally Z. 2006 Accuracy of the Raypex-4 and

Propex apex locators in detecting horizontal and vertical root fractures: an in vitro study. SADJ 61(6):244–247

D’Cruz L. 2006 Off the record. Dent Update 33(7):3�0–3�2, 3�5–6, 3��–400

Leisnert L., Mattheos N. 2006 The interactive examination in a comprehensive oral care clinic: a three-year follow up of students’ self-assessment ability. Med Teach 28(6):544–548

Olmez A., Tuna D., Oznurhan F. 2006 Clinical evaluation of DIAGNOdent in detection of occlusal caries in children. J Clin Pediatr Dent 30(4):287–2�1

Onodera K., Kawagoe T., Sasaguri K., Protacio-Quismundo C., Sato S. 2006 The use of a bruxchecker in the evaluation of different grinding patterns during sleep bruxism. Cranio 24(4):2�2–2��

Scully C., Kalantzis A. 2005 Oxford handbook of dental patient care. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Scully C., Wilson N. 2005 Sensitive oral health care. Quintessence Publishers, London

Shintaku W., Enciso R. Broussard J., Clark G.T. 2006 Diagnostic imaging for chronic orofacial pain, maxillofacial osseous and soft tissue pathology and temporomandibular disorders. J Calif Dent Assoc 34(8):633–644

Tan E.H., Batchelor P., Sheiham A. 2006 A reassessment of recall frequency intervals for screening in low caries incidence populations. Int Dent J 56(5):277–282

s0070s0070

This page intentionally left blank