07Car Assmnt & MBTI - McCaulley

Transcript of 07Car Assmnt & MBTI - McCaulley

http://jca.sagepub.com

Journal of Career Assessment

DOI: 10.1177/106907279500300208 1995; 3; 219 Journal of Career Assessment

Mary H. McCaulley and Charles R. Martin Career Assessment and the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator

http://jca.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/3/2/219 The online version of this article can be found at:

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

can be found at:Journal of Career Assessment Additional services and information for

http://jca.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Email Alerts:

http://jca.sagepub.com/subscriptions Subscriptions:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.navReprints:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.navPermissions:

http://jca.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/3/2/219 Citations

at Bayerische Staatsbibliothek on April 6, 2010 http://jca.sagepub.comDownloaded from

219-

Career Assessment and the Myers-BriggsType Indicator

Mary H. McCaulley and Charles R. MartinCenter for Applications of Psychological Type, Inc.

Gainesville, FL

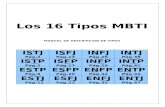

The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI; Myers & McCaulley,1985) is used at each stage of career assessment and career counseling.Based on Jung’s theory of psychological types, the psychodynamicmodel of the MBTI is useful for self-understanding and life-longdevelopment. MBTI type descriptions characterize 16 types at theirbest; provide positive, self-affirming goals; and note blind spots andproblems to avoid. MBTI type tables apply Jung’s theory to groups; typetables for careers not only validate Jung’s theory, but provide ways forlooking at occupations attractive to each of the 16 psychological types.Career counselors use type tables to help clients see the fit betweentheir preferences and career families and to highlight careers especiallyworth considering. The MBTI problem-solving model is a useful toolin the career planning process. Finally, counselors who understand theMBTI find it useful for individualizing counseling approaches andstrategies to the type preferences of their clients.

History and Applications of the MBTI

HistoryThe MBTI is a theory-based instrument. The theory is the part of that

monumental work of C. G. Jung, the Swiss psychologist, described in hisPsychological Types (Jung, 1971). Jung described his types as an attempt tofind a few general principles to understand the multiplicity of points ofview he encountered in working with people. The components of his modelare four fundamental mental processes (sensing, intuition, thinking, andfeeling) and two attitudes toward the world around us (extraverted orintroverted). For each of the types, Jung described a specific configurationof the components to create a picture of that type’s path toward individuationor the development of consciousness.The MBTI is a questionnaire developed by Myers and Briggs to see if it

was possible to &dquo;indicate&dquo; Jung’s types so that Jung’s theory could be testedand, if validated, put to practical use. Career assessment was a motivationfor creating the MBTI. Myers saw many people in World War II trying to bepatriotic but hating the war work they were doing. She hoped Jung’s ideascould be used to provide a better fit between personality and work.Myers and Briggs were two very gifted women, Isabel Briggs Myers and

her mother, Katharine Cook Briggs. Briggs first discovered Jung’s book

Published and copyright @ 1995 by Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc. All rights reserved.

at Bayerische Staatsbibliothek on April 6, 2010 http://jca.sagepub.comDownloaded from

220

and studied it carefully because it fit into work she had been doing on herown to identify individual differences. Both mother and daughter studiedJung’s work line by line. Twenty years of type watching convinced them ofthe validity of Jung’s model. The story of this intellectual journey can be readin Katharine and Isabel: Mother’s Light, Daughter’s Journey (Saunders,1991) and Gifts Differing (Myers with Myers, 1980).Myers created the MBTI, working alone in her home, from 1942 until her

death in 1980, developing and refining a series of forms. In the early 1950s,working at home with no outside financial support, she conducted alongitudinal study of 5,355 medical students from 45 medical schools,following up the students 5 years later to study academic achievement,and again in the early 1960s to study specialty choice. Her results werepresented at the American Psychological Association convention in 1964. Thisstudy is reviewed in the research section of this article.

In 1957, her work came to the attention of Educational Testing Service(ETS) through one of the medical schools. ETS collected data on collegestudents and, in 1962, published the MBTI as a research instrument (Myers).Grant at Auburn and a few others discovered the MBTI and dissertationsbegan to appear. In 1968, the ETS bibliography contained 81 references.

In 1975, the nonprofit Center for Applications of Psychological Type(CAPT) was formed by Myers and McCaulley in Gainesville, Florida tofurther research and applications of the MBTI. Also in 1975, ConsultingPsychologists Press became the publisher and in 1976, for the first time, theMBTI was listed in CPP’s catalog, no longer a research instrument butready for application. By then, the CAPT bibliography had 337 entries.

In 1979, 1 year before her death, Myers completed her major popular work,Gifts Differing (Myers with Myers, 1980) and saw the formation of theAssociation for Psychological Type (APT), a membership organization forpersons interested in her work.

In the following 20 years, interest in the MBTI rapidly increased. It is nowone of the most widely used personality measures and has been translatedinto languages worldwide. A revised manual appeared in 1985 (Myers &

McCaulley). As of January 1995, the CAPT Bibliography for the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (Center for Applications of Psychological Type) showsover 4,000 entries. A number of popular books, many concerned with worklife, have recently appeared (Hirsh & Kummerow, 1989; Kroeger withThuesen, 1992; Lawrence, 1993; Provost, 1989, 1990, 1992; Quenk, 1993;Tieger & Barron-Tieger, 1992).

MBTI ApplicationsAll applications of the MBTI are meant to show how type differences

can be used constructively in making individual decisions, understandingand communicating with others, and helping groups be more productive. TheMBTI is not about identification of psychopathology. It is about developingstrengths and life journeys toward increasing consciousness and competence.

Counselors use the MBTI for individual, family, and career counseling.Educators use it to address the problem, &dquo;How does a teacher with one

at Bayerische Staatsbibliothek on April 6, 2010 http://jca.sagepub.comDownloaded from

221

favorite teaching style reach a classroom of students with 16 favoritelearning styles?&dquo; Increasingly educators are using the research on typedifferences in motivation, aptitude, achievement, learning styles, andpreferences for media to design new ways of learning for the 21st century.In organizations, the MBTI is used for leadership development, teamwork,managing for change, understanding work requirements and work styles,and career planning. In the religious community, the MBTI is used forunderstanding type differences in ministry and spirituality.How can one instrument have so many diverse uses? The answer is that

Jung’s model is based on differences in the ways human beings take ininformation and make decisions-perception and judgment. These differencesoperate in every waking action-and in all aspects of life.

Jung’s Model and the Myers-Briggs Type IndicatorThe model of psychological types uses four bipolar preferences:

(a) extraversion or introversion, (b) sensing or intuition, (c) thinking orfeeling, (d) judging or perceiving. It assumes that every human being goesback and forth between each pole of each preference (i.e., sometimesextraverts and sometimes introverts). All human beings are born with thecapacity to use all poles, but each person has a (probably inborn) preferencefor one pole of each preference over the other. In normal development, aperson finds one pole more interesting and is motivated to spend moreenergy on the activities for that pole. This focused energy leads to theexpertise, habits of mind, and characteristics associated with the chosenpreferences. The important point is that the preferences lead to qualitativedifferences. A sensing type is not simply nonintuitive. A sensing type will-indeed, must-use both sensing and intuition, but will develop a whole setof characteristics different from another person who has followed theintuitive path. Characteristics attributed to types are not traits; they areexamples of the results of energy directed toward developing specificpreferences.

The Foundation: Four Preferences

Extraversion (E) or Introversion (I) describe attitudes toward the world.When extraverting, we turn our attention to the outside world, people,objects, and the changing scene around us. People who prefer extraversiontend to give weight to these outer activities and events and want to bepart of the action. People who prefer introversion tend to give weight to theconcepts and ideas that explain and underlie what goes on in the world. Incareer choices, extraverts gravitate toward activities where there is muchtalk, action, and contact with others-sales or outdoor work, for example.Introverts gravitate to careers where ideas need to be understood andorganized, as in computer programming or social sciences. MBTI datasuggest that extraverts are in the majority in the United States withestimates from 60% to 70%.

Sensing (S) or Intuition (N) are the basic mental processes of perceiving.When we use sensing, our minds are concerned with using our five sensesto perceive the immediate situation, what is real and tangible-the facts of

at Bayerische Staatsbibliothek on April 6, 2010 http://jca.sagepub.comDownloaded from

222

the case. When we use intuition, our minds are concerned with perceivingpossibilities, what we can imagine, the abstractions or theories or symbolssuggested by the facts. In career choices, sensing types are attracted towork where the products can be seen and measured-for example,construction, hands-on patient care, civil engineering, or sales. Intuitivetypes are more attracted to work that requires the big picture, a futureorientation, or use of symbols, such as strategic planning, science,communication, or the arts. MBTI data suggest that about 75% of people inthe United States prefer sensing. Relatively more intuitive types go on tohigher education; about 60% to 65% of college teachers prefer intuition.Intuitive types are in the majority in all fields of counseling.

Thinking (T) or Feeling (F) are the basic mental processes of judging ordecision-making. Jung describes these as two rational mental processes. Whenwe use thinking, we weigh our decisions objectively, with logical analysis.When we use feeling, we weigh our decisions in terms of our values-thepeople, things, and ideas we care about. Thinking types are drawn to careersin engineering, science, finance, or production where logical analysis is apowerful tool. Feeling types are drawn to careers where skills in communicating,teaching, and helping are valuable tools. The TF scale is the only scale toshow male-female differences, with more males preferring thinking and morefemales preferring feeling. (However, female engineers are more likely to preferthinking, and male counselors are more likely to prefer feeling.)Judging (J) or Perceiving (P) indicates whether we use a judging mental

process (T or F) or a perceiving mental process (S or N) when we are in theextraverted attitude. The JP scale was implicit in Jung’s model and madeexplicit by Myers and Briggs. The scale has two purposes. It describesimportant characteristics observable in extraverted behavior. It is also the keyMyers used to indicate Jung’s dynamic configuration of each of the 16 types.Judging types prefer to collect just enough data to make a decision. They

tend to live their extraverted lives in a decisive, planful, organized way.Perceiving types prefer to keep options open for new developments, deferringdecisions in case something new and interesting turns up. They live theirextraverted lives with curiosity, anticipation of change, and spontaneity.Judging types are in the majority (about 55%) in the general population andare found in large numbers (60-80%) among managers and executives inbusiness, industry, government, and academia.

Type Dynamics and Lifelong DevelopmentAlthough everyone uses daily all four mental processes-sensing, intuition,

thinking, and feeling-each mental process has its own motivation or sphereof activity. Jung’s model assumes that equal development of all four wouldlead to lack of focus and an undifferentiated personality. His model assumesthat one of the four will emerge as the leading or dominant process, givingbalance and direction to the personality. Dominant sensing types areoriented toward full experience of the activities of daily life; dominantintuitives are oriented toward achieving future possibilities and visions;dominant thinking types seek logical order in understanding and engaginglife; dominant feeling types seek to live and work to achieve their values.

at Bayerische Staatsbibliothek on April 6, 2010 http://jca.sagepub.comDownloaded from

223

Jung described eight types depending on whether the dominant mentalprocess is used in the extraverted or introverted world. For example,extraverted thinking types seek to bring logical order to the world aroundthem; introverted thinking types want internal order-logical consistencyin the ideas that explain their world.Jung (1971) mentioned briefly a second, auxiliary mental process also

brought into consciousness, &dquo;different from the dominant in every respect&dquo;(p. 406). From that statement, Myers deduced that the dominant andauxiliary must be opposite both in extraversion or introversion and injudging (T or F) or perceiving (S or N). Myers’ MBTI types take into accountboth the dominant and auxiliary mental processes. The result is that whereJung has two dominant thinking types, extraverted thinking and introvertedthinking, Myers describes four dominant thinking types, extraverted thinkingwith sensing as auxiliary (ESTJ), extraverted thinking with intuition asauxiliary (ENTJ), introverted thinking with sensing as auxiliary (ISTP),and introverted thinking with intuition as auxiliary (INTP). Similarly, thereare four types with sensing dominant, four with intuition dominant, and fourwith feeling dominant.

Jung also discussed the two preferences left relatively unconscious, thetertiary process and the inferior process, opposite the dominant and slowestto develop (because most of the energy has gone to developing the dominant).The details of type dynamics and their representation in the MBTI arediscussed in the MBTI manual and in Gifts Differing.The point for career assessment is that the unit of measurement for the

MBTI is the person who indicates a four-letter type, not the four preferencesseparately. Counselors work with individuals, not scales, and much is lostif the MBTI is used without taking type dynamics into account. For example,the MBTI describes eight types of extraverts, each with a common tendencyto turn outward more than inward but each with unique ways in whichextraversion appears. For example, ENTJ extraversion shows in fast-moving, visionary, tough-minded action for future goals; ESFP extraversionshows in lively, sociable enjoyment of the activities of the present moment.

For readers unfamiliar with the MBTI, here is an example of the typedynamics of ENFP, a type often attracted to the counseling profession. ForENFP, the dominant mental process is extraverted intuition-the greatestmotivator is new possibilities out in the world. The introverted feelingauxiliary provides balance. An ENFP overcommitted to too many excitingpossibilities uses the balance of the auxiliary to slow down and retiretemporarily to the world of introverted feeling: &dquo;Which of these possibilitiesis most important? How do I make sure I do not fritter away my energieson trivial matters? How do I set priorities by what I care most about?&dquo;Time management usually does not work with ENFPs, but using theauxiliary, introverted feeling does help with choices. ENFPs use intuitionand feeling most often and most consciously. They may neglect their tertiarythinking and, especially, their inferior sensing, which they may characterizeas &dquo;grim reality&dquo; or &dquo;unnecessary bean counting.&dquo; ENFPs are adapted totoday’s world of rapid, global change. Dominant intuitive types gain energyfrom new possibilities; when they have mastered them, they are ready to go

at Bayerische Staatsbibliothek on April 6, 2010 http://jca.sagepub.comDownloaded from

224

on to new adventures. This is in contrast to their opposite, ISTJ, introvertswith sensing dominant and extraverted thinking as auxiliary. For ISTJ, thechallenge comes from mastering the world as it is, relying on past experience;their inferior intuition does not trust &dquo;unsubstantial&dquo; imagination andvague possibilities. ISTJs may have more difficulty in a rapidly changingworld where past experience is no longer a useful guide to the future.Myers wrote descriptions of each of the 16 types, using Jung’s model of

type dynamics. Each description is based on the characteristics of the typewith good development of the dominant and auxiliary. Each descriptionends with a brief statement of problems to be expected if the auxiliary is notdeveloped enough to balance the dominant.

Jung’s model assumes life-long development toward individuation orconsciousness. In midlife statements such as, &dquo;Is this all there is?&dquo; often leadto exploration of the tertiary and inferior functions (Corlett & Millner,1993; Quenk, 1993).Do not assume Jung’s model is as straightforward as it is described here.

Although, Jung and Myers both assumed there is an inborn predispositionfor the pathways of one’s type, development is not always smooth. Familiesand cultures can support the development path of a type or disconfirm it.Jung talked about falsification of type which in extreme cases can lead toneurosis or exhaustion. This is why MBTI users help individuals verifythe best-fit type before using MBTI concepts in assessment.

MBTI Psychometrics

Indicating Type for IndividualsThe MBTI is a forced-choice questionnaire. The choices are between

equally valuable opposites, not right or wrong or good or bad. Some questionsprovide choices between key words; other questions provide choices betweenphrases. Omissions are permitted, because the best estimate of type isbetween clear preferences, not random guesses.The MBTI has been successfully administered to sixth-graders but it is

best used with persons who read at least at an eighth-grade level.There have been many forms over the years. The current forms are Form

G (126 questions) and Form G Self-Scorable (92 questions). Form F (166questions) includes all but 2 Form G questions, plus unscored researchquestions. Form J (290 questions), created by Saunders (1987) after Myers’death, begins with the 166 Form F questions and adds all questions in anyother published form of the MBTI. Form K (131 questions) is Form G, plusother questions needed for expanded computer reports.Hand scoring of Form F, Form G, or Form K takes about 5 minutes using

templates that give the item weights for scored items. Each response to eachquestion is scored separately. Answers may be weighted 0, 1, or 2; itemweights take into account omissions, social desirability, and prediction tototal score. The sums of the item weights for E, I, S, N, T, F, J, and P arecalled total points. They are transformed into preference scores such as E 17or N 25. Preference scores consist of a letter showing the direction ofpreference and a number showing the consistency of reporting the preference.

at Bayerische Staatsbibliothek on April 6, 2010 http://jca.sagepub.comDownloaded from

225

Ties in points are broken in the direction of I 01, N 01, F 01, and P 01.Preference scores are the unit of measurement for the scales but the typeformula made up of letters for the four preferences-ESTJ, INFP-is the unitof measurement for the individual.

Jung’s theory and every step of Myers’ work to create the MBTI assumea choice of one pole of a preference over the other leads to qualitativelydifferent (dichotomous) characteristics. However, because most researchmethods assume a normal curve and a continuum, not dichotomies, IsabelMyers provided a formula for transposing preference scores to continuousscores so that researchers could report their findings consistently. In thisformula, a midpoint is set at 100. The numerical portion of the preferencescore is subtracted from 100 for E, S, T, and J, and added for I, N, F, and P.Thus, continuous scores for S 17 become 83 and for N 17 become 117.Continuous scores are only for research.

Computer scoring is available for Form F, Form G, Form J, and Form K.In addition to basic scoring, generating types, and type descriptions, FormsF, J, and K can be scored for expanded reports showing subscales for EI, SN,TF and JP. Form J can also be scored for the Type Differentiation Indicatorwhich adds to the expanded reports seven &dquo;Comfort Scales.&dquo; Because theMBTI does not have questions to identify pathology, the Comfort Scales arenot used for diagnosis, but are helpful in identifying issues in typedevelopment. Form J is available only to persons qualified to purchaseLevel C instruments; all other forms are available to persons who havecompleted coursework in tests and measurements to be qualified to purchaseLevel B instruments. The publisher can provide information on other MBTItraining programs it will accept for qualification to purchase the MBTI.

MBTI Data for GroupsThe MBTI is also a measure for groups. The type table showing Myers’

placement for each type is the unit of measurement for groups. Table 1 showsa type table from the Atlas of Type Tables (Macdaid, McCaulley, & Kainz, 1986).The Atlas and its associated MBTI Career Report Manual (Hammer &

Macdaid, 1992) are major resources for career assessment and counseling.The data in Table 1 are from 673 persons who described themselves as

vocational or educational counselors on answer sheets submitted for

computer scoring by the Center for Applications of Psychological Type(CAPT). Notice that the dominant function for each type is printed in bold.The counselor sample shows 59% extraverts, 61% intuitives, 64% feelingtypes, and 55% judging types. The most frequent type is ENFP whose 113counselors make up 16.79% of the sample. The least frequent is ESTP with7 counselors (1.04%). A column to the right of the table shows the numberand percentage for the major type groupings. Pages 30 through 38 of theMBTI manual (Myers & McCaulley, 1985) describe the placement of typesand interpretation of type groupings on the type table.

Myers called the four columns of the type table Combinations of Perceptionand Judgment and believed these groupings were most useful for careerassessment. Her reasoning was that the best career choices let us focus onthe aspects of life that most interest and motivate us (i.e., let us perceive

at Bayerische Staatsbibliothek on April 6, 2010 http://jca.sagepub.comDownloaded from

226

Note. · = 1% of sample. This type is one of a series of type tables from the CAPT DataBank of MBTI records submitted to CAPT for computer scoring between 1971 and June,1984. This sample was drawn from 59,784 records with usable occupational information,coded at the time of scoring, from the total data bank of 232,557. From Myers-Briggs TypeIndicator Atlas of Type Tables by G. P. Macdaid, M. H. McCaulley, and R. I. Kainz, 1986,p. 207, Copyright 1986 by Center for Applications of Psychological Type, Gainesville,Florida. Reprinted with permission of the publisher.

at Bayerische Staatsbibliothek on April 6, 2010 http://jca.sagepub.comDownloaded from

227

with sensing or intuition) and make decisions the way that comes mostnaturally (i.e., use thinking or feeling judgment.) Such career choices shouldremain motivating and challenging because they let us do what comesnaturally with our best skills.The ST types (sensing with thinking) she called the practical and matter

of fact types and predicted they would be most attracted to work requiringtechnical skills with facts and objects. In the second column, SF types(sensing with feeling) are called the sympathetic and friendly types and areattracted to work that gives practical help and services to people. In the thirdcolumn, NF types (intuition with feeling) are called enthusiastic andinsightful. They are attracted to careers that require understanding andcommunication with people. Finally, in the NT column (intuition withthinking) are the logical and ingenious types, who are attracted to work withtheoretical and technical developments. Notice that 43.98% of the counselorsfall in the NF communication column. As an example of the more generalquestions type tables can pose, consider these facts. Three-fourths of thepopulation prefer sensing. About two-thirds of counselors and psychologistsprefer intuition, usually associated with feeling. This NF preference isconsistent with predictions from type theory. What does it say about theprobability that counselors may be missing ways of helping the majority ofsensing types, whose minds work so differently from their own? (An ENFPcounselor was told by an ISTJ client, &dquo;You keep talking about my beinghappy. Forget happy! I just want you to help me solve my problem!&dquo;)

Examples of MBTI Research Relevant to CareersMBTI career research is concerned with questions about type differences

in choice of careers, choice of specialties, career satisfaction, and careersuccess. The current bibliography has over 100 articles, research projects,dissertations, and theses that have examined the relationship betweentype and careers. Applications have far outstripped supporting research. Inthe pressures of daily work, rich data sources lie untouched.

The Myers Longitudinal Medical StudiesMyers conducted a longitudinal study of 5,355 freshman medical students

from 45 medical schools. The students entered medical school in the early1950s, mainly from the class of 1955. She followed up 4,556 who reporteda primary specialty in the 1963 Medical Directory of the American MedicalAssociation (AMA). Ten years later, with McCaulley, Myers followed up4,953 listed with primary specialties in the AMA records of December 31,1973 (see McCaulley, 1977 for a report of all studies). Representativesignificant findings for both 1963 and 1973 showed that extraverts wereattracted to orthopedic surgery, obstetrics and gynecology, and pediatrics;introverts had chosen pathology, anesthesiology, and psychiatry. Sensingtypes chose anesthesiology, obstetrics and gynecology; intuitive types chosepathology, neurology, and psychiatry. There were few significant TF and JPdifferences, but pathologists were more likely to prefer thinking andpsychiatrists were more likely to prefer perceiving. An example of thedifference one letter can make is shown in the 1963 comparison of the listsof the two introverted feeling types: ISFP and INFP. For ISFP, anesthesiology

at Bayerische Staatsbibliothek on April 6, 2010 http://jca.sagepub.comDownloaded from

228 J

headed the list and psychiatry was second from the bottom; for INFP,psychiatry headed the list with anesthesiology at the bottom. The ISFPsconcentrated on the observable symptoms and readings of their instruments;the INFPs on what could be read between the lines.

A comparison was made of changes in ranks of specialties over the decadefrom 1963 to 1973. Nineteen percent of physicians changed primary specialtyover the decade; all types changed specialty but intuitives significantlymore often moved to specialties more compatible with their MBTI preferencesof 20 years before.

Comparisons of Career Rankings From Atlas of Type TablesMyers reasoned that the most successful career choices would allow

scope for a person’s favorite way of perceiving (sensing or intuition) andfavorite way of judging (thinking or feeling.) This is why she emphasized ST,SF, NF, and NT for understanding career matching. She recognized that EIand JP were also important, but mainly in the work environment (e.g.,indoors, outdoors, high people contact, structure, or crisis management).CAPT conducted a series of data bank analyses to see if comparison of high

and low rankings for careers grouped by ST, SF, NF, and NT would be moreinformative than career rankings by IJ, IP, EP, and EJ. The data aresummarized in the MBTI Career Report Manual. The 208 careers in the Atlasof Type Tables were ranked from highest to lowest for each type, based onthe percentage of that type in the various careers. For example, all 208careers were ranked for ISTJs, with the careers having the highestpercentage of ISTJs at the top of the list and those careers with the lowestpercentage of ISTJs at the bottom of the list.A general test of the theory was made by looking at the percentage of

overlap between the top 50 careers for opposite types (e.g., ESTJ and INFP).There was an average of only 5% overlap. A more specific test of Myers’reasoning was carried out by comparing the percentage overlap of top 50careers for types that shared the same mental processes but oppositeattitudes (e.g., ISTJ vs. ESTP) with the percentage overlap of top 50 careersof types that shared the same attitudes but had opposite functions (e.g., ISTJvs. INFJ). Supporting Myers’ hypotheses, types with the same middleletters averaged 41% overlap, whereas those with the same outer letters butopposite middle letters averaged only 3.5% overlap, a number that is verysimilar to the percentages found for types where all four preferences wereopposite. In other words, the pairing of the combinations of perception andjudgment (ST, SF, NF, and NT) provide us with more information aboutcareer choice. As noted in the Career Report Manual, distributions with a3.5% overlap are separated by 4.23 standard deviations, whereasdistributions with a 41% overlap are separated by 1.65 standard deviations.This study suggests MBTI types clearly find their way into different careers.

Research Comparisons of MBTI Type TablesThe Selection Ratio Type Table (SRTT; Granade, 1987; McCaulley, 1985;

Moody & Granade, 1993) computer program was designed to compare MBTItype tables. Written originally for Myers’ longitudinal medical study, it

at Bayerische Staatsbibliothek on April 6, 2010 http://jca.sagepub.comDownloaded from

229

was used to answer questions such as, &dquo;What types entered orthopedicsurgery?&dquo; &dquo;What types practice direct patient care?&dquo; The word selection inSRTT comes from its initial use to look at career selection data, but SRTTcan be used for many other relationships, dropout being the most frequent.The program compares a sample type table (e.g., Myers’ 415 psychiatristsfrom the 1973 follow-up) with a reference type table (e.g., the 4,953 physiciansin the follow-up for whom primary specialty was known). The programcomputes two kinds of data for each type and each of the type groupings ofa type table. The first is a ratio of the observed frequency in the sample table,compared to the expected frequency from the reference table distribution.The second statistic is chi-square (or a Fisher’s Exact Test if numbers in cellsare less than five). The table presents for each type and grouping the number,percentage in the sample, ratio, and significance based on chi-square.

Instructions for interpreting SRTT (McCaulley, 1985) caution againstoverinterpreting SRTT data, given the fact that 44 sets of analyses have beencarried out on the same data set. With rapid advances in contingency tableanalysis, more complex methodologies for comparing type tables are beingdeveloped. The advantage of SRTT is that it is not just for the researcher.With SRTT, the busy practitioner can quickly and easily organize a largenumber of data for ready analysis and/or later reference.

Type Differences in Career SatisfactionThere is considerable evidence that careers attract more of the types

who, in theory, would find the work interesting. One would expect, then, thatpersons in careers that fit their type preferences would express higher jobsatisfaction. There is some evidence to support this hypothesis.Smith (1988) examined the ability of type-knowledgeable judges to

determine an individual’s level of career satisfaction, based solely on thejudges’ knowledge of the person’s four-letter type and a brief description ofthe job and job title. Judges were able to predict a significant amount ofvariance in job satisfaction based on knowledge of four-letter type andoccupation alone. However, judges were unable to make statisticallysignificant predictions to satisfaction when they were given only theinformation on preference scales (E or I, S or N, T or F, J or P). Smith’s worksupports the importance of using the type, not just individual preferences.

Olguin (1988) hypothesized that types would differ in the aspects of the jobmost important for their job satisfaction. He found that workers rated assignificantly more important those aspects of their work predicted to be of moreinterest to their types. These studies by Smith (1988) and Olguin (1988) areexamples of the kinds of type-knowledgeable and sophisticated research thatneeds to be expanded to verify other career hypotheses of type theory.

Apostal (1988) reported MBTI type differences in student reports of theircareer interests and perceived competencies. Those who expressed interestsin producing ideas had preferences for intuition and thinking; and those whoexpressed interests in being a helper of persons had preferences for sensingand feeling. Those who saw themselves as skilled analyzers of data wereintroverted, as skilled producers of ideas were intuitive and perceiving,and as skilled helpers of persons were feeling types.

at Bayerische Staatsbibliothek on April 6, 2010 http://jca.sagepub.comDownloaded from

230

Resignations and turnover can indicate lack of work satisfaction. Early workby Laney (1945) related turnover to degree of congruence between type andwork tasks at the Washington Gas Light Company. Extraverts were more likelyto stay on outdoor jobs and introverts on desk jobs; extraverts and feeling typeswere more likely to stay on sales jobs. Sensing-judging (SJ) types were morelikely to stay with the company whether the jobs were mechanical, clerical,or other. Laney’s research is summarized in the MBTI manual (Myers &

McCaulley 1985, pp. 92-93.) Roush (1989) examined voluntary resignation fromthe United States Naval Academy and found that cadets with preferences forintroversion, intuition, feeling, and perceiving (less typical preferences formilitary cadets) were significantly more likely to resign.

To study career satisfaction, Myers added to the MBTI Form G answersheet an optional question for persons who reported they are working: &dquo;Do

you like it 0 A lot, 0 O.K., 0 Not much. In preliminary studies from the1991-1992 CAPT data bank of 75,628 Form G records (McCaulley, Macdaid,& Granade, 1993), the satisfaction option was answered on 49,841 records.Decisive extraverts (EJ) significantly more often chose A Lot and thespontaneous introverts (IP) significantly more often chose Not much. Amore extensive report on a larger sample will be reported at the llthinternational conference of the Association of Psychological Type in July,1995. At that time we shall be looking for data to understand how generalthe phenomenon is over different kinds of careers or whether it appears thatthe more ebullient EJs and more reserved IPs are showing a type-relatedresponse set. We shall also look more closely to see if types more attractedto careers also report more satisfaction with those same careers.

Career Research Within a Single CareerSome researchers have sought to verify type hypotheses through a close

examination of the members of a single career. Richard (1994) examined notonly the psychological type of practicing lawyers, but also the relationshipbetween type and satisfaction. Law is concerned with deciding on impersonalprinciples that are fair to all (i.e., the use of thinking judgment). In Richard’ssample of 1,202 lawyers (Table 2), 76% of the practicing lawyers in thesample preferred thinking judgment. Note that 41% of the sample fall in thelogical and ingenious NT column, 35% in the practical and matter-of-fact STcolumn, 15% in the communications NF column, and 9% in the sympatheticand friendly SF column. Half of the sample is in the four corners of the typetable, the TJ logical decision-makers. Richard found significantly moreNTs in litigation and more STs in the specialties that require great attentionto details-taxes, trusts, and estates.

Consistent with the CAPT data bank findings, the ESTJs and ENTJs hadhigh mean job satisfaction scores. They were significantly higher than allof the IPs, even the INTPs who were overrepresented in the sample oflawyers. Thinking and judging types consistently scored higher than feelingand perceiving types on job satisfaction. The types most frequent in legalpractice also were most satisfied with their profession.

Jacoby (1981) studied 333 accountants from the Washington, D.C. officesof three of the &dquo;Big Eight&dquo; public accounting firms to look at specialty

at Bayerische Staatsbibliothek on April 6, 2010 http://jca.sagepub.comDownloaded from

231

Note. · = 1% of sample. From L. R. Richard (1994). Psychological type and job satisfactionamong practicing lawyers in the United States. (Doctoral dissertation, Temple University,1994). Dissertation Abstracts International, 55(04), 1654B. (University Microfilms No.AAC94-22677). Adapted with permission of the author. The 1,202 lawyers (369 femaleand 851 male) returned usable data from a random sample of 3,014 American BarAssociation members admitted to the bar after 1-1-67, excluding those not in activepractice (judges, professors, retired) and foreign lawyers. Data consisted of MBTI FormG, the Hoppock Job Satisfaction Blank, and a demographic questionnaire constructed bythe author.

at Bayerische Staatsbibliothek on April 6, 2010 http://jca.sagepub.comDownloaded from

232

choice and success. Twenty percent of the accountants fell in one type, thethorough, detail-oriented, responsible ISTJs. Among the auditors, ISTJs were36% of partners and 42% of managers. When success in the accountingfirms was measured by level of advancement to partner or manager,significantly more analytical and decisive TJ types and the ISTJ type werein the successful group. Sensing types were significantly more frequentamong successful auditors, whereas intuitives were in the majority amongsuccessful accountants specializing in tax accounting and managementadvisory services, positions that required more communication and innovation.

These few examples of career research with the MBTI indicate directionsfor learning more about important issues of career selection, reasons forsatisfaction, retention, and career success. As more practitioners becomeresearchers and share their experiences through research, the career counselorwill have much more precise information for assessment and counseling.

Applications of the MBTI in Career CounselingAn understanding and appreciation of one’s psychological type can play

an important part in the career exploration and decision-making process.It is, however, only one part of the process. No career decision should be madeon the basis of one instrument alone, and MBTI data are best used inconjunction with other career assessment measures of interests, values,skills, and development. MBTI preferences alone should never be used toexclude (or determine) a particular career choice. Type tables of careers withreasonable samples show all 16 types represented, though not in equalnumbers (as demonstrated in Table 1 and Table 2).The MBTI is designed to indicate preferences, not competencies. MBTI

responses do not show whether a person is a mature example of a type, withgood command of perception and judgment, or a less mature examplestruggling more with the liabilities of the type than in command of theassets. Particular care should be used when the MBTI is used in

organizations, especially when making employment decisions. MBTIquestions are straightforward. As with other psychological assessment,persons wishing to protect themselves can bend answers at least somewhattoward their picture of their employer’s expectations.Type theory is sometimes seen as limiting-perhaps because MBTI type

tables can lead to the impression that the MBTI puts people in boxes. Theappropriate application of the MBTI is to see the results in terms of life-longdevelopmental pathways that open options for fulfilling the motivations andgifts of an individual.

Job Analysis Using the Lens of Type TheoryType theory may be used for job matching without administering the

MBTI. For instance, look at job requirements to see what preferences theyrequire. Do the main requirements of the job require similar or oppositepreferences? A job requiring careful attention to detail, a quiet workenvironment, and an orderly approach fit well with preferences for sensing,introversion, and judging. A job requiring careful attention to detail, long-range strategic planning and a focus on customer service requires opposite

at Bayerische Staatsbibliothek on April 6, 2010 http://jca.sagepub.comDownloaded from

233

preferences-sensing, intuition, introversion, and extraversion. Jobs neednot be pared down to fit narrow type preferences; everyone can use less-preferred preferences when a situation requires it. It is useful, however, tolook carefully at jobs that require constant use of opposing type preferences.

Understanding MBTI types can improve interviews of candidates withoutadministering the MBTI. For example, a job may require long-range strategicanalysis, on-the-spot decisions, and building top-flight work teams. Theinterviewer might work from the hypothesis of an ENTJ &dquo;job type.&dquo; How havecandidates responded to similar assignments? Was the assignment stressfulor challenging? Have they avoided the ENTJ problems of underestimatingthe need of communication to build cooperative support groups (F)? or ofoverlooking necessary detail work (S) as they rushed forward? Whether ornot the candidate is ENTJ, these job-type questions can bring out importantfacts about candidate-job match.

Self-Understanding and Self-EsteemBy far the most frequent report from career counselors is that MBTI

feedback promotes better understanding of oneself, of one’s strengths andweaknesses, and one’s future directions. With type theory as a basis, clientscome to understand the reasons why past work experiences were energizingor draining, why communication with coworkers and superiors was successfulor went sour. Counselors use these insights to confirm the accuracy of theMBTI report or to raise questions about uncertainties about the best-fit type.For example, one introverted student whose mother had strongly encouragedsocial participation (cheerleader, beauty queen) discovered her joy in theworld of ideas at the university and claimed her introversion. A workerwhose sensing parents had criticized her &dquo;crazy ideas&dquo; and lack of commonsense discovered her intuition was trustworthy. &dquo;I feel as if I have been

throwing away a gift. I feel more integrated within myself.&dquo; Discussions oflife history and values in light of type preferences are not only confirmingfor the client, but improve the counseling relationship because the client feelsunderstood and confirmed. Weaknesses in the skills of the less-preferredfunctions are seen as the natural result of spending more time and effort todevelop their opposite preferred functions. The new understanding ends self-blame and leads to action plans to put more trust in the dominant andauxiliary and also to learn the less-interesting skills of the third andinferior functions when they are needed.

Academic Advisement and Educational Decisions

The MBTI is used in several ways for career assessment with students,where counseling involves academic advisement, academic achievement,and learning styles. Academic advisement and choice of major often includeconcerns about self-expectations and family-expectations. Students whoare usually in the transition between dependence on families andindependent adulthood may find it is useful to compare their current MBTItype with &dquo;the type my parents want me to be.&dquo;

Type tables from the Atlas of Type Tables can inform students of thelikelihood that careers they are considering will have many or few people

at Bayerische Staatsbibliothek on April 6, 2010 http://jca.sagepub.comDownloaded from

234

with similar interests. (Unpublished data at the Isabel Briggs MyersMemorial Library at CAPT show that type patterns for college majors aresimilar to the patterns in comparable careers.)

Students sometimes find that the career they have dreamed of sincechildhood attracts few of their type. It can be disheartening to enter acareer where you assume you will find kindred spirits, only to discoveryou see the world much differently from those around you. We call this&dquo;inadvertent pioneering.&dquo; It can be challenging to pioneer on purpose-toenter a career where you are different from most people, with the plan offinding a niche where you can contribute new viewpoints or skills. However,the discrepancy between the dream career and type data should nevercause the student to give up the dreams, but should generate a discussionof the need to go out and explore the dream career in real life, to see if itreally will give the satisfactions expected.The MBTI can also be helpful in advising students about the tasks of

passing the courses needed for their fields of study. A consistent MBTI findingis that intuitive types receive higher mean scores on academic aptitude teststhan do sensing types (Myers & McCaulley, 1985). Academic aptitude measuresare designed to identify abilities needed for academic work-dealing withconcepts and ideas (I) and with symbols, abstractions, and theories (N).Sensing types, particularly extraverts with sensing, often come to advisementwith a sense that they have to struggle harder than their classmates and thatthey are not intelligent enough to meet requirements of fields to which theyaspire. Counselors have resources to show students how to use their ownlearning strategies when the professor is on a different wavelength and howto achieve well academically (Lawrence, 1985, 1993; Provost, 1992).

Assessment and MatchingThe MBTI sets a framework for understanding skills, interests, and

values. Are the values of a client what we might expect from knowledge ofhis or her type? For example, high rankings for economic values are frequentfor ESTJ, and rare for INFP. High rankings for altruism are frequent forINFP and rare for ESTJ. Discussions around these patterns are not designedto move persons toward consistency for their type; they are designed toilluminate past history and the individual differences within each type.Type tables provide valuable facts for assessment and matching.

Information available in the Atlas of Type Tables (Macdaid et al., 1986), theMBTI manual (Myers & McCaulley, 1985), the Career Report Manual(Hammer & Macdaid, 1992), and the Career Reports available from computerscoring by CPP and CAPT provide listings of careers most frequently andleast frequently chosen by each type. The careers at the top of the list notonly broaden options, but also give insights into the characteristics ofcareers that offer scope for the gifts of the type.MBTI results suggest questions to ask during assessment: Does this

career call for use of your preferences? How much will it stretch you touse your less-liked preferences? Of course, no work will be a perfect fit fortype. The goal is to find work that most of the time gives scope for a type’sinterests and skills.

at Bayerische Staatsbibliothek on April 6, 2010 http://jca.sagepub.comDownloaded from

235

Information GatheringType preferences can influence the kinds of activities the client finds

attractive or is inclined to avoid. For example, a client with preferences forextraversion, feeling, and perception (EFP) is more likely to network widely,make cold calls for information interviews, and do volunteer work. A clientwho prefers introversion, thinking, and judging (ITJ) may resist theseactivities, but enjoy research in the library or career resource center. Bothways of gathering information are important and necessary at differenttimes. A knowledge of type helps counselors determine which activities aclient is most likely to pursue and which may be stumbling blocks.

Decision-MakingJung’s model and the MBTI are based on differences in taking in

information (S and N) and making decisions (T and F). Myers (1970;Lawrence, 1993) developed a problem-solving model to encourage controlledand conscious use of all four of these mental processes, the two preferred andthe two less-preferred.The model makes explicit many activities of career assessment. In the

context of careers, the counselor would lead the client through the followingsteps:

1. Use your sensing to examine what your situation is. What are thefacts from your education, your work history, your family history,the present economic situation that show the realities you musttake into account as you make your decisions?

2. Use your intuition to look beyond the present to new possibilities.Use your imagination to see options you haven’t consideredbefore. Have you been stuck in old ways of looking at your work?Are there patterns in your past experience that you have beenmissing? Can you see opportunities in your present situation thatyou have missed? Try to expand your possibilities from a yearahead to 10 years ahead, even to the end of your life.

3. Use your thinking to make a critical and impersonal analysis ofthe consequences of choosing options you have come up with.Look especially hard at the dreams you have had for years. Whatcould be the up-side of choosing each option? What could be thedown-side? Be as tough-minded as you can.

4. Use your feeling to look at how your decision will affect otherthings you care about. How would your choices affectrelationships with family, friends, coworkers? How about yourvalues of security, excitement, meeting challenges, or living lifewith integrity? How will the choices you are considering affectthe things in life you care most about?

Individuals’ strengths and weaknesses in applying this method of problem-solving will tend to correspond to their type dynamics. The counselor alertsthe client to natural tendencies to put most weight on the steps that involvethe dominant and auxiliary function and skip over or find more difficult thesteps of the third and fourth functions. Individuals who report using the

at Bayerische Staatsbibliothek on April 6, 2010 http://jca.sagepub.comDownloaded from

236

MBTI model have rated themselves more effective problem-solvers oncethey become more conscious users of their less-preferred mental processes(Yokomoto & Ware, 1982).

Planning and Taking ActionOne of the final components of the career counseling process involves

helping the client to engage in planning and goal-setting and helping themto act on their decisions. A knowledge of the MBTI helps clients andcounselors refine these strategies. Types differ in their tendencies to setspecific or broad goals; immediate or long-term goals; concrete, tangiblegoals; or personal lifestyle or visionary goals. Types differ in the ways theyimplement intermediate goals and tasks-working harder in school, gettingoutside training, writing resumes, interviewing.The tempo of extraverts and introverts can be different at this stage, with

introverts taking more time to get their plans firmly in mind, whileextraverts move into action. Counselors will recognize when introverts arestaying too long in planning, or when extraverts move precipitously intoaction without taking useful time for reflection. In data from The OhioState University medical students (McCaulley, 1978, p. 193), the fast-moving, decisive EJ types reported making decisions to enter medical schoolearly and being sure of their choices. The more thoughtful, open, IP medicalstudents reported that they were slow to decide on medical school and werestill not sure it was a good choice.

The Career Counseling ProcessThe field of career assessment and counseling has developed a wealth of

information about career maturity, career development, and the strategiesof job seeking and job-finding. This information has been codified into stepsthat clients should take. Not all MBTI types will see the relevance of allsteps. Clients with a preference for judging (J) more easily engage in theorganized and scheduled task completion counselors often assume isnecessary to the successful navigation of these steps. Clients with apreference for perceiving (P) may not fit as easily into a model of counselingthat insists they plan and follow the steps in a systematic way. This, ofcourse, does not absolve them of the need to complete tasks. Rather, theyhave their own strengths (e.g., seizing new opportunities and workingthrough stuck plans) that may achieve goals without initially appearing tofit with structured career planning.

The Client-Counselor RelationshipHow is the MBTI best introduced into the process of career counseling?

Counselors are careful in administering and interpreting the MBTI so thatclients confirm their best-fit type. Counselors explain both the power andlimitations of type theory and the MBTI. Counselors help clients understandthat their type preferences can have an impact not only on their careerchoice, but on how they learn and relate as well. Type should not be usedto exclude career choices; but type can provide a nonthreatening languagefor exploring how they may differ from others in their chosen field.

at Bayerische Staatsbibliothek on April 6, 2010 http://jca.sagepub.comDownloaded from

237

Counselors find the MBTI useful in the counseling process itself. If aclient completes the MBTI and verifies, for example, that ESTJ is his or hertype, the counselor has clues to help build rapport and conduct sessions ina way that is respectful of the client’s type preferences. The counselorprepares to provide structure; to give direct, to-the-point communication; andto assign homework tasks. The client will want to set clear, realizablegoals. Do not expect much time to be spent on discussion of the meaning oflife. In covering the steps of career assessment for an ESTJ, the counselorwatches for problems related to premature closure or underestimating theimportance of decisions on human relationships.

SummaryThe MBTI provides five tools for career assessment and counseling.

Understanding one’s type provides an appreciation of one’s gifts and apathway to life-long development. Type tables provide the content formatch-mismatch of one’s interests and careers. The decision-making modelprovides a strategy to trust one’s strengths and watch out for blind spots.Counselors use an understanding of type differences to plan the best waysfor each type to cover the steps necessary for good career planning. Finally,counselors learn to &dquo;talk the language&dquo; of the client’s type and developbetter strategies to improve the client-counselor process itself.

ReferencesApostal, R. A. (1988). Status of career development and personality. Psychological Reports,

63, 707-714.CAPT Bibliography for the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. Gainesville, FL: Center for

Applications of Psychological Type. (Updated twice a year; available in bound copy ordiskette.)

Corlett, E. S., & Millner, N. B. (1993). Navigating midlife: Using typology as a guide.Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Granade, J. G. (1987). The Selection Ratio (PC-DOS Program) [Computer software].Gainesville, FL: Center for Applications of Psychological Type.

Hammer, A. L., & Macdaid, G. P. (1992). MBTI: Career Report manual. Palo Alto, CA:Consulting Psychologists Press.

Hirsh, S., & Kummerow, J. (1989). LIFETypes. New York: Warner.

Jacoby, P. F. (1981). Psychological types and career success in the accounting profession.Research in Psychological Type, 4, 24-37.

Jung, C. G. (1971). The collected works of C. G. Jung: Vol. 6. Psychological types (H. G.Baynes, Trans., rev. by R. F. C. Hull). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kroeger, O. with Thuesen, J. M. (1992). Type talk at work. New York: Tilden.

Laney, A. R. (1945). Occupational implications of the Jungian personality function-typesas identified by the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. Unpublished master’s thesis, GeorgeWashington University, Washington, DC.

Lawrence, G. D. (1993). People types and tiger stripes (3rd ed.). Gainesville, FL: Center forApplications of Psychological Type.

Lawrence, G. D. (1985). A synthesis of learning style research involving the MBTI. Journalof Psychological Type, 8, 2-15.

Macdaid, G. P., McCaulley, M. H., & Kainz, R. I. (1986). Atlas of type tables for the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. Gainesville, FL: Center for Applications of Psychological Type.

McCaulley, M. H. (1977). The Myers longitudinal medical study. Gainesville, FL: Centerfor Applications of Psychological Type.

at Bayerische Staatsbibliothek on April 6, 2010 http://jca.sagepub.comDownloaded from

238

McCaulley, M. H. (1978). Application of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator to medicine andother health professions. Gainesville, FL: Center for Applications of Psychological Type.

McCaulley, M. H. (1985). The Selection Ratio Type Table: A research strategy for comparingtype distributions. Journal of Psychological Type, 10, 46-56.

McCaulley, M. H., Macdaid, G. P., & Granade, J. G. (1993, May). Career satisfaction andtype: Data from the CAPT data bank. Unpublished manuscript.

Moody, R., & Granade, J. G. (1993). The Selection Ratio Type Table (PC-MacintoshProgram) [Computer software]. Gainesville, FL: Center for Applications of PsychologicalType.

Myers, I. B. (1962). Manual: The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. Princeton, NJ: EducationalTesting Service.

Myers, I. B. (1993). Introduction to type (5th ed.). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting PsychologistsPress.

Myers, I. B., & McCaulley, M. H. (1985). Manual: A guide to the development and use ofthe Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Myers, I. B. with Myers, P. B. (1980). Gifts differing. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting PsychologistsPress.

Olguin, A. (1988, April). The relative contribution of dispositional factors to job satisfaction.Paper presented at the meeting of the Western Psychological Association, Burlingame, CA.

Provost, J. A. (1989). Procrastination: Using psychological type concepts to help students.Gainesville, FL: Center for Applications of Psychological Type.

Provost, J. A. (1990). Work, play, and type: Achieving balance in your life. Palo Alto, CA:Consulting Psychologists Press.

Provost, J. A. (1992). Strategies for success: Using type to do better in high school and college.Gainesville, FL: Center for Applications of Psychological Type.

Provost, J. A. (1993). Applications of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator in counseling: Acasebook (2nd ed.). Gainesville, FL: Center for Applications of Psychological Type.

Quenk, N. L. (1993). Beside ourselves: Our hidden personality in everyday life. Palo Alto,CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Richard, L. R. (1994). Psychological type and job satisfaction among practicing lawyers inthe United States. Dissertation Abstracts International, 55(04), 1654B. (University MicrofilmsNo. AAC94-22677)

Roush, P. E. (1989). MBTI type and voluntary attrition at the United States NavalAcademy. Journal of Psychological Type, 18, 72-79.

Saunders, D. R. (1987). Type Differentiation Indicator manual: A scoring system for FormJ of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Saunders, D. R. (1989). MBTI Expanded Analysis Report manual: A scoring system for FormJ of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Saunders, F. W. (1991). Katharine and Isabel: Mother’s light, daughter’s journey. Palo Alto,CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Smith, C. (1988). A comparative study of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator and the MinnesotaImportance Questionnaire in the prediction of job satisfaction. Unpublished doctoraldissertation, Ball State University, Muncie, IN.

Tieger, P. D., & Barron-Tieger, B. (1992). Do what you are. Boston: Little, Brown, &

Company.Yokomoto, C. F., & Ware, J. R. (1982). Improving problem-solving performance using the

MBTI. Proceedings of the American Society for Engineering Education (ASEE) AnnualConference, 163-167.

at Bayerische Staatsbibliothek on April 6, 2010 http://jca.sagepub.comDownloaded from

239

Resource OrganizationsAssociation for Psychological Type. Nonprofit membership organization. Regional and

international conferences. Bulletin of Psychological Type. Distributes Journal of PsychologicalType. Headquarters: 9140 Ward Parkway, Kansas City, MO 64114. Telephone 816-444-3500,fax 816-444-0330.

Center for Applications of Psychological Type. Nonprofit organization for research;professional programs and consultation; publisher and distributor of books and materials;scoring, research consulting. Isabel Briggs Myers Memorial Library. MBTI Bibliography. 2815NW 13th Street, Suite 401, Gainesville, FL 32609. Telephone 904-375-0160, fax 904-278-0503.

Consulting Psychologists Press, Inc. Publisher of the MBTI. Publishes test materials,handbooks, and professional and popular books related to MBTI Scoring. Responsible forprotection of Myers’ copyrights and for licensing translations. 3803 East Bayshore Road,Palo Alto, CA 94303. Telephone 415-969-8901, fax 415-969-8608.

at Bayerische Staatsbibliothek on April 6, 2010 http://jca.sagepub.comDownloaded from