06

-

Upload

madhu-prasher -

Category

Documents

-

view

192 -

download

1

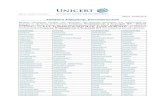

Transcript of 06

NEW COMPARISON

A Journal of Comparative and General Literary Studies

Published for the British Comparative Literature Association

Editors: Susan Bassnett (Comparative Literary Theory and Literary Translation,

University of Warwick) Theo Hermans (Dutch, University College London) Holger Klein (Modern Languages and European History, University of East

Anglia)

Editorial Board: Leon Burnett (Literature, University of Essex). Eva Fox-CAI (English and Related Literatures, University of York), Kei th Hoskin (Classics/Education, University of Warwick), George Hyde (English and American Studies. University of East Anglia), Andre Lefevere (Germanic Languages. University of Texas at Austin), Susan Melrose (Drama and Theatre Studies, Murdoch University, Australia), Philip Mosley (Comparative Literature, Pennsylvania State University). Saliha Paker (London/lstanbul), Robert Pynsent (School of Slavonic and East European Studies, University of London), Brigitte Schultze (Slavonic Studies, University of MaindTranslation Studies Centre, University of Gottingen), Christopher Smith and Clive Scott (Modern Languages and European History, University of East Anglia), Stephen Walton (Scandinavian Studies, University College London), Peter V. Zima (Comparative Literature, University of Klagenfurt).

NEW COMPARISON is published twice yearly, in the Summer and Autumn.

Administration and Subscriptions: Dr Susan Bassnett. New Comparison, Graduate School of Comparative Literary Theory and Literary Translation, University of Warwick, Coventry CV4 7AL.

Prices and subscription rates: see last page.

Editorial address: Dr Theo Hermans, New Comparison. Department of Dutch, University College London. Gower Street, London WClE 6BT.

Books for review, etc.: to Dr Holger Klein, New Comparison. School of Modern Languages and European History, University of East Anglia, Norwich NR4 7TJ.

Typing and layout: Carol Haines

0 Individual authors

Printed at the University of East Anglia

NEW COMPARlSON

A J o u r n a l o f C o m p a r a t i v e a n d G e n e r a l 1 2 ~ ~ e r , ~ r \ S ~ u d ~ c

N u m b e r 6 : L i t e r a r y T h e m e s Autumn 1988

E d i t e d by Holger Klein

H O L G E R KLElN ( N o r w ~ c h ) T h e m e s and T h e m a t o l o g y

ANGELIKA CORBINEAIJ-HOFF'M4NN ( k l a ~ n z ) V e n i c e a t F i r s t Sight: P r o l e g o m e n a for a N r w V ~ e w on l l i r r n ; ~ l I<, \

A N D R E E MANSAll (Toulouse) Venice P r e s e r v e d : His tory , Myth and L i t ~ r a r y ( ' r e d [ ~ o n

HANS-GEOHG G R ~ ~ N I N G ( M a c e r a t e ! T h e " T r a i t o r t o h is People": A C o n t r i b u t i o n t o t h e P h e n o m e n o l o g y of T r e a c h e r y in L i t e r a t u r e

GYORGY E. SZONYl ( S z e g e d ) V a r i a t i o n s o n t h e h ly th of t h e M a g u s

T E R E N C E DAWSON (Singapore) V i c t i m s of t h e i r o w n C o n t e n d i n g Pass ions : I lnexptbctcd I)c,;~rh in Adolphe , Ivanhoe , a n d W u t h e r i n g H e ~ g h t s

ELISARETH RRONFEN ( M u n ~ c h ! Dia logue wi th t h e D e a d : T h e D e c e a s e d S e l o v c d as kluat.

S lEGHlLD BOGUMIL ( B o c h u m ) I m a g e s of L a n d s c a p e in C o m t e m p o r a r y F r e n c h I'octr!.: Ponge , C h a r and Dupin

WALTER RACHEM ( R o c h u m ) N a t u r e and P e r c e p t i o n : Vers ions of a I l ~ a l e c t i c . 111

E u r o p e a n C i t y P o e t r y ZlVA B E N - P O R A T ( T e l Aviv) A u t u m n P o e m s a n d L i t e r a r y Impress ionism: C o n c e p t u a l ~ s a t ~ o n , T h e m a t i z a t i o n and C l a s s i f i c a t i o n

WENDY M E R C E R (London) F r o m Idyll t o Arsenal : T h e C h a n g ~ n g I m a g e o f G e r m a n y In F r a n c e a s s e e n through t h e Work of X a v ~ e r M a r m e r 11808-1892)

J U L I A N COWLEY (London) T h e A r t of t h e Improvisers : J a z z and F i c t ~ o n in P o s t - B e b o p A m e r i c a

E. W. H E R D ( O t a g o ) Tin D r u m and S n a k e - C h a r m e r ' s F l u t e : S a l m a n H u s h d ~ e ' s D e b t t o G u n t e r G r a s s

REVIEWS

R E P O R T O N 'WORK IN P R O G R E S S '

NEWS

OBITUARY

THEMES AND THEMATOLOGY

Holger Klein (University o f East Anglia)

"If ever a word was set up to he knocked down", Levin w i t t i l y remarked

twenty years ago, "it is that forbidding expression ..." ("Thematics ...I1,

p.94). Yet we have been bombarded with so many more formidable terms

in various spheres o f cr i t ical inquiry that this particular one may surely

pass. I t is useful: scholars writ ing in French have talked o f th6matolop;ie

at least since Van Tiegham (though he and many others used i t purely as

a translation o f Stoffgeschichte), i t has i ts obvious equivalents in other

Romance languages (tematologia, tematologia, etc.) and is known also e.g.

in Dutch (without the aigu on the el. Moreover, against variously

expressed doubts and opposition1 Thematologie is gaining ground in

cerman2 - not just to dissociate new efforts from what most perceive as

the stuffiness o f traditional Stoffgeschichte and Motivgeschichte, but to

designate a much wider field. Levin prefers thematics, which also has

obvious equivalents; however, there is a tendency to call the'matique/

thematiek1Thematik the thematic elements in particular works and the

methods o f their analysis,3 which again is only one area of the field. On

balance, then, thematology is preferahle as a general term for that branch

o f learning concerned, whether theoretically or i n practice, with the study

of l i terary themes. Using i t contributes a l i t t l e towards a convergence

o f terms and the notions they express - a development which, though

perhaps not essent ia~,~ is certainly apt to help.

The problem is not, o f course, that scholars working in different

languages use different words - that has been our general lot "After

Babel" and is largely remediable by dictionaries5 - but that l i terary

scholars (not exclusively, but perhaps more than those in the other

humanities) using the same language often employ identical terms for

different phenomena and vice versa.6 The reasons for this state o f

affairs, and for the unlikelihood of i ts being wholly overcome afforr!s

opportunities for speculation on the business of crit icism as well as on i ts

materiaL7 That is not my present concern. Nor do I wish to dwell once

more8 on the fact that "theme" and "motif" (as opposed to "motive") - along with a host of related terms - have no generally agreed signifieds

for those writ ing in ~nglish,' that scholarly usage of theme and r n d

drastically varies in French,'' and that, finally, the distinction between

S t o f f and M& is nei ther uniform in German' ' nor, in the dominant

t radi t ion, very serviceable. Jos t urges t h e res t of t h e world t o adopt t h e

German dis t inct ion ( a s if ag reemen t about it existed), obviously in eve ry -

one ' s own language; however , th is would only spread confusion and the

need f o r e l abora te contortions. Weisstein, on t h e o the r hand, r emarks it

might b e helpful if t h e German word S t o f f (which has f requent ly been

t aken ove r in o the r languages)'' w e r e t o b e dropped in favour of T h e m a

(p.137) (and S t o f f t o b e r e t a ined only in t h e sense of Rohstoff /subject

mat ter /mat ikre) . Although h e immediate ly s t eps back from this suggestion , it is more real is t ic and m o r e promising than Jos t ' s and has a l r eady been

frui t ful ly t aken up. If we add t o i t ano the r t e n t a t i v e suggestion, t h i s t i m e

by Rremond, t h a t t h e d i f f e rence be tween theme and motif ( a s opposed t o

mot ive ) l3 i s not o n e of kind but of degree,14 w e may a r r ive a t a

p rac t i cab le scheme.

T h e s o o f t e n l amen ted terminological chaos and wrangling should not

mesmer ize us. Nor must th is d e b a t e b e allowed t o obscure t h e f a c t t ha t ,

par t icular ly in t h e last t w o decades , thematology (under wha teve r name)

has made g rea t progress in cons t ruc t ing f r ameworks of s tudy and opening

perspect ives which, besides account ing fo r a g r e a t dea l of exci t ing work

al ready done, encourage fu r the r promising labours. Tracing i t s own

evolution and ref lect ing on i t s a i m s and me thods a r e t w o ac t iv i t i e s

incumbent on eve ry branch of academic study. Much has been achieved

fo r thematology in both directions, but t h e process must of cour se

continue.

In principle, thematology has t w o a r e a s of p rac t i ca l work, two

approaches t o l i tera ture . One looks mainly a t single t ex t s , perceiving in

them o r endowing them with a s t r u c t u r e of meanings. This might be

cal led a hor izontal , o r dynamic, o r syn tagmat i c approach. T h e o t h e r looks

a t un i t s of con ten t known t o r ecur in var ious (o f t en qu i t e d i s t an t and

unconnected) works, and makes those un i t s i t s principal object of study;

th is might b e cal led a ver t ical , o r s t a t i c , o r pa rad igmat i c approach. As

in o the r branches of ou r discipline, me taphors a r e o f t e n needed t o descr ibe

o u r sub jec t s and what w e d o with them, though they all h a v e the i r

l imita t ions and drawbacks. Of t h e t h r e e metaphorical pairs t h e las t one

s e e m s on t h e whole t h e leas t p rob lemat i c a n d will b e employed here.

l n t r a t ex tua l and in t e r t ex tua l could b e an a t t r a c t i v e a l t e rna t ive , w e r e i t not

t h a t t h e t e r m is by now somewha t charged. Indeed, t h e links, over laps and

differences between thematology and studies o f intertextuality in the

narrower, manageable (as opposed to the universal) sense st i l l await

investigation. 15

The syntagmatic approach to themes belongs mainly to those Wellek

and Warren call "intrinsic" studies (and cherish) - magnificently exemplified

by the New Crit ics and by practitioners o f werkimmanente Interpretation. 16

Themes here have an established place which was never called in

question. They are an integral part of the functional web which fuses

elements o f content and form (Gehalt and Gestalt) into a unique whole -

including cases o f deliberate jarring and disjunction, o f course.

The paredigmatic approach to themes, the one to which many

scholars writ ing in French have unti l fair ly recently confined th6matologie

(Trousson being a conspicuous protagonist), and which flourished as - to

quote the t i t le o f one o f Frenzel's weighty contributions - Stoff-und

Motivgeschichte in German, is to be aligned with the range o f "extrinsic"

studies in Wellek and Warren's system, though they, for slightly different

reasons than croce,17 regrettably did not think much of i t . I8 Inclusive-

ness serves the cause o f l i terary crit icism better than exclusivity. Resides,

not only is the division into intrinsic and extrinsic studies itself problem-

atic, but, while pure concentration on content, ideology, message, etc.

certainly does an injustice to the l i terary work as art, many such works

are inadequately construed in isolation from their environment and

historicity. (And the very vogue for "intrinsic" studies during the mid-

century decades had i ts own historical background that bears thinking

upon.)

I t is perfectly true that many - by no means only early - paradig-

maticstudies of themes are l i t t le more than collections of examples with

summaries and at best cursory comment. Against the strictures which this

kind of thematological study has attracted one may justly argue that even

such collections can be very useful, though they demand (l ike author

concordances and other invaluable tools, on the production of which

l i terary scholars have spent untold years) cogitative complementation.

Moreover, just as with religions, cr i t ical approaches and methods should

be judged not so much by their adherents than their potential. One can

furthermore point out that in discussions of thematology great value has

often been placed on reception, and due regard demanded for the relatiorl-

ship of thematic instance and i ts immediate context19 and that there exist

numerous studies which do o f fe r incisive observations and conclusions.

Both thematic approaches are fruitful, both can enhance our under-

standing and appreciation o f l i terature as well as of i t s relationship to i t s

various contexts. Moreover: in convincing examples o f either sort, they 20 tend to complement one another : the interpretation o f the single work

gains by the consideration o f i t s thematic units in larger contexts, and the

tracing o f the fortunes o f such units within a given synchronous or dia-

chronic scope gains by the close analysis o f the units' functions in

significant texts. What does manifestly not work well and lies, I suspect,

at the root o f much anguish and trouble is the identical use o f termino-

logical systems in both approaches. A way forward offers i tsel f i f one

does not only differentiate between the two approaches, as Pollmann (esp.

pp.182-86) has perhaps most clearly done, but extends this differentiation

to terminology (something he emphatically rejects).

In a given text (or a group o f closely related texts) a theme is

whatever element - more usually an accumulation or rather constellation

o f elements2' - is important enough to characterize the whole or a portion,

making i t possible t o talk o f i t as being about this or that ( in accordance

with the role o f the theme) centrally, mainly, or only in part. In this

sense, any content element can be the theme or contribute t o i t , as may

also formal elements.22 I t is in syntagmatic interpretations that further

distinctions can be helpful. And here some o f the traditional terminology

comes to i ts best use. For, i f there is a measure o f agreement intra- and

interlingually, i t resides in thinking o f theme as a larger, mot i f as a

smaller unit o f significant and distinct content,23 with or trait, i f one

wants t o go further, being st i l l smaller.24 One may add, depending on

what is found in a text, such terms as formula, leitmotif, and symbol to

describe particular uses t o which specific, usually small units are put.

Evidently, identifying a theme - "theming" a text (Prince), "labelling"

(Rimmon-Kenan) or "naming" i t (Hamon) is t o some extent conditioned by

the context of the person who does it.25 Yet there are l imi ts t o arbit-

rariness in "seeing as"26: i t would e.g. require someone o f more than

angelic tongue to convince many that pearls are a theme in Hamlet. On

the other hand, there are personal l imitations t o theme perception,

especially i f a theme is not made explicit in a text. The same applies

t o theme recognition. Yet one can constructively identify a particular

theme (taking i t as what Leroux lp.4501 calls a "th8me possible" or

"intensionnel") in a given work without realising that i t has in itself a

history (is " rke~" or "extensionnel").

In paradigmatic studies these distinctions, useful in the other

approach, hinder rather than help perception and communication. If, as

scholars have frequently observed, a -/trait can become a M-/motif

and vice versa, and i f a StofT/theme may basically be stripped down to

one or several Motive, i f a 1- may through a given work acquire the

characteristics of a StoTf27 - if, in other words, thematic units can change

their appearance and function from text to text, as overwhelming evidence

shows they do - i t is surely appropriate not to hypostasize terms built on

al l sorts of special and variable factors such as area of provenance, first

known or best known example, constellations o f components, frequency of

use in one or another shape. Rather, one might accept, with Bremond

(p.417). that what these elements have in common is their thematic

quality, and for paradigmatic purposes call them, as Dyserinck

(Kompararatistik, p.110) suggests, comprehensively: themes. Advocating

this usage does not entail promoting "nebulous" (Chardin, p.30) imprecision,

but seeks to remove fut i le rigidity which neither meets the volatile

conditions of the material nor the endlessly variable circumstances and

forms o f i t s reception.

Furthermore, there are no convincing grounds to l imit ing (as has been

common in theoretical treatments of thematology unti l about 1970) such

thematic studies to some specific kinds, notably human situations, types,

heroes and heroines. Dyserinck, by contrast, divides themes into two large

groups (pp. l ]Of.): those of various, extra-l i terary provenance,28 and those

that already have a tradition in literature. And he rightly stresses that

both groups are worthy of treatment. He details sub-headings within both

groups, but i t is more practical here to draw for such specificity on

Prawer, who already shows an equally inclusive stance, listing f ive main

groups (pp.99f.; additions that seem apposite are indicated by parentheses) :

(1) Natural phenomena and man's reaction to them (add: man-made

environments and objects); eternal facts of human existence; perennial

human problems and patterns of behaviour (add: ideals, ideas, moods and

feelings). (2) Recurring motifs (better called small themes) in l i terature

and folklore (add: t ~ ~ o i ) . ~ ' (3) Recurrent situations; historical events

(add: conditions). (4) The representation of (professional and other) types.

(5) The representation of named personages "from mythology,30 legend,

earlier l i terature or history". Prawer has no di f f icul ty in pointing to

worthwhile studies for each group, his as well as Dyserinck's (and more

recently e.g. Chardin's) comprehensive concept o f thematology is close to

actual scholarly practice.

Applied syntagmatically to individual texts, thematology can con-

tr ibute to increasing, in the framework o f integrative analysis, the

aesthetic pleasure to be derived from them, and moreover play a v i ta l

role in establishing the scheme o f values they manifest as well as, should

they happen to propound or suggest theses, help to highlight them. Para-

digmatically applied as systematic surveys and/or developmental histories

o f themes ( in the comprehensive understanding of the term), thematology

can contribute to our insight into l i terature in general, and beyond that

into the societies and cultures in which i t was and is being produced. I f

in the course o f such work l i terary scholarship and cr i t ic ism come into

close contact with, draw on and in their turn contribute something to

other disciplines - philosophy and history o f ideas, the analysis and history

o f mentalities, folklore studies, a r t history, sociology, economic and

polit ical history, and many others - so much the better. This should not

deter us but on the contrary be an added incentive and cause for joy.

Not only no man, as Donne says, but no academic discipline is an island,

or rather, should behave as i f that were the case. Moreover, as among

others Pollmann (pp.13f.I has emphasized, the relevance o f l i terary studies

as such has come under very non-idealistic scrutiny, and this f ield belongs

to those where such relevance can most easily be shown - among other

things because the paradigmatic approach rarely gets far wi th an exclusive

concentration on Li terature wi th a capital L, but must cast i t s net more

widely," and indeed does well also look at altogether different kinds of

discourse. 32

Even apart from such considerations a strong fascination attaches to

following the history of a theme or o f a group o f themes: tracing their

increasing or diminishing use and resonance in various periods, studying

their preponderant af f in i t ies wi th certain genres as well as the special

at t ract ion to them o f certain authors, movements, geographical, national

and linguistic entities, and seeing their l i terary representation in relation

to that in other kinds o f texts and in other arts.33 The diff icult ies are

numerous. What constitutes the theme (or whatever other term is chosen,

as the likelihood o f general conformity is small), how much i t may be

varied and st i l l be identifiable - that is by no means always clear.34 The

vastness of l i terature (let alone the arts) and the l imits o f an individual's

spheres o f competence, knowledge and energy can hardly guarantee

exhaustiveness even within certain bounds;35 that aim36 is in itself not

unquestionable, but i f i t is abandoned, the problem arises o f what may be

deemed representative samples. Thirdly, there is the interface o f para-

digmatic with syntagmatic study - how far must, how far can one enter

into the fabric of particular works and take into account the function o f

a theme even i f one's aim is the theme itself, or at least a section or

stretch of i t s history? These and other dilemmas wi l l presumably continue

to beset such investigations and rise in proportion with the scale and

ambition of the enterprise. The fascination nevertheless exerts i ts sway.

Numerous scholars in many countries have, despite real obstacles and all

sorts o f adverse dicta and cautions from other colleagues, continued to

write paradigmatic contributions to thematology as well as syntagmatic

ones. The bibliographies are ful l of them.

One may properly doubt whether comparative l i terature as a disci-

pline has not only a subject differing from those of literary studies

confined to one language or one region or state, but also i ts own, di f fer-

ent methodology. With, for instance, ~ a ~ d a ~ ~ and Jost (Introduction, p.24)

I incline to the view that it does not. Thematological work is to some

extent feasible within a confined national or linguistic framework; how-

ever, the more the paradigmatic approach comes to the fore, the more

obviously such restrictions must recede.38 Thematology is, alongside the

study of genres and that of many movements, a prime domain of compara-

t ive (or general)39 literature; thematic studies are the kind of work in

which i ts ef for ts yield particularly f ru i t fu l results.

Some words about this number of New Comparison are indicated. In line

with our usual policy, the lion's share o f the available space has been

devoted to a specific topic - Literary Themes. A number o f scholars were

invited to wr i te articles on a specific theme of their own choice. It

seemed worthwhile to find out, in this manner, how thematic studies are

being conceived of and practised in various places at the present time, and

to gather the results between two covers. Clearly, a conference would

have been best and might have led to a more intensive interaction of

viewpoints and methods. However, this was not feasible. Instead, the

contr ibut ions coming in d id not only g o through t h e usual bi la teral

edi tor ia l process (without , r eade r s will b e amused t o n o t e while applauding

t h e principle, any persuasion t o unify terminology), but w e r e c i rcular ised

among t h e authors,40 t o whom I wish t o express s ince re thanks. Thus

t h e s e a r t i c l e s a r e based on a knowledge of o n e another , which in s o m e

c a s e s a t leas t g a v e r ise t o cross-references . More one could not aim a t

within t h e given constra ints . T h e s tud ies t r e a t a va r i e ty of t h e m e s - though t h e r e exis t i l luminating c o n t a c t s - and use very d i f f e ren t pro-

cedures , which i s all t o t h e good. And in e a c h case , I think, t h e method

employed shows i t s p rac t i ca l usefulness a s well a s demons t ra t ing t h e

vigour and scope of thematology in general , even though t h e l imita t ions

of s p a c e a l lowed only f o r modest samples.

1. See e.g. Frenzel , S to f f - und Motivgeschichte, p.30; Risanz, "Zwischen S to f fgesch ich te ...", pp. 148, 159; Knapp, "Robbespierre ...Iv, p. 130. Where no de ta i l s a r e given in these notes , t h e contr ibut ion is listed in t h e Se lec t Bibliography below.

2. See e.g. Reller, Thei le , p.49, Dyserinck, even Frenzel ( l a t e , in Motive ..., p.xiv), J o s t in "Grundbegriffe", Dyserinck.

3. S e e e.g. Rrunel/Pichois/Rousseau, p.117 (though t h e dis t inct ion tends t o f a d e o u t l a t e r ) and s o m e con t r ibu to r s t o Pogt ique 16 (in con t ra s t t o t h e organisers: Alleton, Rremond, Pavel , pp.395f.; fu r the rmore Pollmann, p.192, n.31. Kurman follows Levin in choosing Themat i c s ; P r a w e r (p.99) uses both (curiously enough as synonyms fo r Stoffgeschichte) a s does Weisstein, while Cors t ius o p t s fo r Thematology. Ei ther i s b e t t e r than Themat i sm, used by Bernard Weinstein introducing Falk.

4. A s J o s t believes, cf . Introduction, p.177, a l s o Czerny.

5. A ~ a r t i c u l a r l v re levant o n e being Wolfgang V. Rut tkowski and R. E. Blake, ~iteraturw~;terbuch/Glossary o f - l i t e r a r y ?erms/Glossaire d e s t e r m e s l i t t&raires , Rerne and Munich: F rancke , 1969.

6. S e e esp. Bisanz, 'S to f f , Thema , Motic", pp.317f., 321f.

7. S e e e.g. Beller, "Von d e r S to f fgesch ich te ...", p.4, Bisanz, "Zwischen S to f fgesch ich te ...", Dyserinck, Komparat is t ik , pp.l09f., Kurman, pp.471.

8. A s I did in "Autumn P o e m s ..." t h r e e y e a r s ago.

9. Even s tudious observat ions and proposals such a s those submi t t ed by Levin in "Motif". Daemmrich in "Themes and Motifs" o r by F reedman will not help, a s t h e e n t i t i e s themse lves a r e not s t a b l e ( see below, p. ).

10. J u s t o n e fu r the r example: Jeune, p.62 and B~ne l /P icho i s /Rousseau , p. 128 against Trousson, Un problhme, p. 13; c f . a l so general ly Chardin, p.27.

11. S e e f u r t h e r Dyserinck, Komparat is t ik , pp.lO8f.; a l so ( t r ea t ing English a s well a s German) Bisanz "Stoff, Thema , Motiv".

12. E.g Raldensperger/Friederich, B i b l i o ~ r a p h y , Trousson, "Plaidoyer", Weissteln (Chap te r heading), e t c .

13. The two are often linked in discussions of motif; however, motive in the sense of motivation, psychological drive, etc., is clearly something else; interest in i t has led to author-centred but highly interesting thematic studies particularly by Gaston Bachelard. Charles Mauron, Georges Poulet, Jean-Pierre Richard as well as the (frequently attacked) Jean-Paul Weber. I t is feasible and preferable to keep the two terms separate; cf. also Weisstein, p.145. Glaser (see esp. Vol.1, p.7) offers a striking recent example o f the results of oscillation between the two.

14. Bremond, p.417, n.2; he even ventures as far as saying: " ... le mot i f peut &re consider6 comme un thkme."

15. The decision for syntagmatic and paradigmatic in this specific application has i ts precedent in Liithi, "Motiv, Zug, Thema ...". For the two senses in which "intertextuality" is now being applied (and an argu- ment for the narrower sense) see Ulrich Broich and Manfred Pfister, eds., Intertextualitat (Tiibingen: Niemeyer, 19851, esp. pp.11-15, 31, 179; see also my discussion o f reception studies in "Preface: Receiving Hamlet Reception", New Comparison 2 (Autumn 19861, 5-13. 1 have not found any references to intertextuality in discussions o f thematology so far.

16. And again championed with passion and severity by Bernard Weinberg in his Introduction to Falk's book.

17. See Croce's review of a book on the Sophonisba theme in Cr i t ica 2 (19041, pp.483-86, and Weisstein's discussion, p.128. Also Croce's essay "Storia di temi ...". 18. Ren6 Wellek and Austin Warren, Theory of Literature (New York: Harcourt, Brace L? World, 1947, 2nd edn 1949, repr. 1956), p.260. A con- venient summary of their and others' standard ohjections is given in Comparative Literature: Matter and Method, ed. A. Owen Aldridge (Urbana: Illinois UP, 1969). Editor's Introduction to Ch.lll "Literary Themes'' pp. 106-08.

19. See Van Tieghern, p.89, Guyard, p.52, Frenzel, Motive, p.xi, Trousson, "Plaidoyer", p.107, Corstius, p.93, Prawer, p.101, etc. An opposite point of view is taken by Sauer (see below, n.31).

20. Cf. Bisanz, "Zwischen Stoffgeschichte ...It, p. 158, Beller, "Thematologie", p.77.

21. Brunel/Pichois/Rousseau, pp.121; see also e.g. Jeannine Jallat, "Lieux balzaciens", Po6tique 16 (1985), pp.473-81, here: 475.

22. See esp. Rimmon-Kenan, p.404f., generally Prawer, p.103, Kaiser, p.90, etc. A practical example o f joining thematology and poetics is Theile's article.

23. Cf. e.g. Levin. "Thematics". ~ .107, Potet, p.376 and 382, Prince, p.425; also: (substhuting Stoff .fo; theme) ~ r e & e l , Stoff- Motiv- und Symbolforschun , p.28, Stoff- und Motivgeschichte, p.12 and Motive, p.v, Greverus, p.39+, Pollmann, p.193, Beller, "Von der Stoffgeschichte ...Iv,

p.39, Kaiser, p.80; and Risanz, "Zwischen Stoffgeschichte ..." p.163 n.42, considers adopting this as the main difference, i n analogy to music.

24. But not so small as the extreme sense o f mot i f advocated by Tomachevski (esp. 268), i.e. as the residual unit o f meaning in every proposition; nor in the related sense o f theme current in linguistics, cf. Rimon-Kenan's discussion.

25. See esp. Hamon, p.431.

26. See esp. Brinker, p.440-43; also Bremond, p.421 and Prince, p.430- 32.

27. See e.g. Frenzel, Stof f - Mot iv- und Symbolfirschunq, pp.23, 73-77 and Stof f - und Motivgeschichte, p.17, Pollmann, pp.182-83, 188, Luthi, "Motiv, Zug, Thema", pp.16, 20, Baeumer, "~be rgang ...", passim, Trousson, Thbmes e t mythes, p.27, Prince, p.427.

28. As opposed e.g. to Guyard, Dyserinck excludes the study o f national auto- and hetero-images (Komparatistik, p.105), which he has so energeti- cally advanced, and gives i t a separate heading (pp.124-131). These images appear, however, as themes in l i terature and cannot simply be hived off.

29. For the enormous development of topology af ter Curtius see esp. the extended research survey by Veit.

30. This corresponds t o long-established practice and theoretical sanction. See esp. Trousson, ~ h k m e s e t mythes ... and e.g. Brunel/Pichois/Rousseau, pp.124-27, though they outline the differences. Chardin (p.29) and others in the volume L a recherche ... argue for completely separating the study o f myths from that o f themes; whereas Weisstein's exclusion o f symbols (p.129) is at least arguable (their study is certainly more profitable in the syntagmatic approach), the exclusion o f myth is neither possible nor desirable.

31. See e.g. Beller, "Von der Stoffgeschichte ...'I, p.15 and Trousson, "Plaidoyer", p.105; also e.g., already Sauer, whose remarks on pp.224 and 227 str ike one indeed as an early recipe for a "Readers' L i terary History". In his radical application, the notion provides ample ammunition for the well-known charge that Stoffgeschichte exhausts itself wi th indiscriminate levelling in the service o f a history o f taste, or - at best - cultural history. (Incidentally, both are neither negligible nor detachable from l i terary history.) By contrast, "High" l i terature above al l st i l l guides the views of Pichois/Rousseau (p. 150). Pollmann (p. 197) handles the issue in a more circumspect manner.

32. For a practical example, see Beller, "Thematologie", pp.85-92; the issue is at least br ief ly considered by Prince, p.433.

33. See Czerny, and for a concrete application e.g. Calvin S. Brown, "Theme and Variations as a Li terary Form", Yearbook o f Comparative and General L i terature 27 (1978). 35-43. In general see the informative dis- cussion by Beller in "Thematologie", pp.dlf., and Giraud's decisive stand (La fable de Daphne, Geneva: Droz, 1969, p.d8), which his study as well as those o f others ful ly bear out. Curiously enough Weisstein, whose concept of, and work in the f ield of the "Mutual Illumination of the Arts" (see his Ch.VII) has proved immensely fruitful, skirts this aspect in his treatment o f thematology.

34. Kaiser's progression from Queen Gertrude's (choric) description o f Ophelia's death to Brecht's "Vom ertrunkenen Madchen" (pp.81-89) demon- strates this as well as Bremond's graph (p.419) or Schulze's deliberations.

35. Though i t seems an obvious step to take, group research as a means o f bridging the gap between material and human capacity has not apparently been employed in work on a specific theme. Thematologists tend to be loners; here is plent i fu l scope for new projects.

36. Stressed e.g. by Sauer, p.227; the problem is pondered with the requisite awe by Brunel/Pichois/Rousseau, p. 127.

37. Gyorgy M. Vajda, "Stand, Aufgaben und methodologische Position der Vergleichenden Literaturwissenschaft in Ungarn", in Aktuelle Probleme der Vergleichenden Literaturforschung, ed. Gerhard Ziegengeist (Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 19681, pp.88-99; here p.95.

38. Cf. e.g. Beller, "Von der Stoffgeschichte ...", p.30 and Prawer, p.176. I t is no accident that thematology has been largely developed by compara- tists and regularly features in surveys o f this discipline, alongside folk tale studies, which have been comparative ah ovo.

39. E.g. Jeune places thematology under Iql i t t6rature g6ndrale - another wide field for terminological wrangling. Simply "Literature" might be best for both comparative and general (as distinct from disciplines studying literature only from one language or one country); hut the odds against replacing traditional nomenclature are high.

40. This was made easier by a grant from the Research Committee of the School of Modern Languages and European History. University of East Anglia, Norwich, which is gratefully acknowledged.

Select Bibliography

Abastado, Claude. "La trame et le licier: Des themes au discours thematique", Revue des Langues Vivantes 43 (1977), 478-91.

Albouy, Pierre. Mythes et mythologies dans la ~ i t td ra ture francaise. Paris: Colin, 1969.

Alleton, Viviane. "Le thkme vu de Babel", Po6tique 16 (19851, 407-14.

Alleton, Viviane, Claude Bremond, Thomas Pavel. "Vers une thkmatique", Podtique 16 (1985), 395-96.

Aziza, Claude, Claude Olivi&i, and Rohert Sctrick, eds. Dictionnaire des types et caractbres littkraires. Paris: Nathan, 1978.

Baeumer, Max L., ed. Toposforschung, Darmstadt: WR, 1973.

Baeumer, Max L. "Uebergang und dialektischer Wechsel von Topos, Motiv und Stoff dargestellt am griechischen Dionysos", in Elemente der Literatur: Beitrage zur Stoff- Motiv- und Themenforschung. FS Elisabeth Frenzel, ed. Adam J. Bisanz and Raymond Trousson with Herbert A. Frenzel. 2 vols ( ~ t u t t ~ a r t : KrBner, 1980j, Vol.1, pp.25-44.

Baldensperger, Fernand, and Werner P. Friederich. Bibliography o f Com- parative Literature. Chapel Hil l : North Carolina UP, 1950, repr. New York: Russel Pr Russel, 1960. Sixth Part: "Literary Themes (Stoffge- schichte)", pp.70-178.

Beller, Manfred. "Von der Stoffgeschichte zur Thematologie: Ein Beitrag zur komparatistischen Methodenlehre", Arcadia 5 (19701, 1-38.

Beller, Manfred. "Thematologie", in Vergleichende Literaturwissenschaft: Theorie und Praxis, ed. Manfred Schmeling (Wiesbaden: Athenaion, 1981), pp. 73-97.

Ben Amos, Dan. Folklore i n Context. New Delhi: South Asian Publishing Co.. 1982.

Bisanz, Adam J. "Zwischen Stoffgeschichte und Thematologie", Deutsche Vierteljahresschrift fur Literaturwissenschaft und Geistesgeschichte 47 ( 197 I), 148-66.

Risanz, Adam J. 'Stoff, Thema, Motiv: Zur Problematik des Transfers von Begriffsbestimmungen zwischen der englischen und deutschen Literatur- wissenschaft", Neophilologus 59 (1 9751, 2 17-23.

Blumenberg, Hans. "Paradigmen zu einer hletaphorologie", Archiv fur Regriffsgeschichte 6 (19601, 7-142.

Bodkin, Maud. Archetypal Patterns in Poetry. London: Oxford UP, 1934, repr. 1963.

Bodkin, Maud. Studies of Type Images in Poetry, Religion and Philosophy. London: Oxford UP, 1951.

Bremond, Claude. "Concept et thkme", Po6tique 16 (19851, 4 15-23.

Brinker, Menachem. "Thkme et interprdtation", Podtique 16 (19851, 435-43.

Rrunel, Pierre. "Le mythe et la structure du texte", Revue des Langues Vivantes 43 (19771, 510-21.

Brunel, Pierre, Claude Pichois, Andr6-M. Rousseau. Qu'est-ce que la IittBrature compar6e?. Paris: Colin, 1983. Ch.6 "Thgmatique et th6ma- tologie", pp. 1 15-34.

Burgos, Jean. "Thkmatique et hermeneutique ou le thhmaticien contres les interpr&tesl', Revue des Langues Vivantes 43 (19771, 522-34.

Buuren, M. B. van. "Le concept de motif", Rapports 48 (19781, 171-76.

Chardin, Philippe. "Approches th6matiques1', in La Recherche en Litt6- rature gCndrale et comparge en France, ed. Daniel-Henri Pageaux (Paris: SDLGC, 19831, pp.27-45.

Chudak, H. "Bachelard et le thkme", Revue des Langues Vivantes 43 (19771, 468-77.

Cirlot, Juan Eduardo. A Dictionary of Symbols, transl. Jack Sage. London: RKP, 1962, 2nd edn 1971.

Clemente, Jose E. Los temas esenciales de la literatura. Buenos Aires: Emece', 1959.

Clements, Robert J. Comparative Literature as Academic Discipline: A Statement of Principles, Praxis, Standards. New York: MLA, 1978. Ch.VII1 "Themes and Myths", pp. 165-79.

Corstius, Jan Brandt. Introduction to the Comparative Study of Literature . New York: Random House, 1968. pp.92-102 in Ch.lll "Literature as Context".

Croce, Benedetto. "Storia di temi e storia letteraria", in Problemi di estetica (Rari, 1910). pp.80-93.

Cryle, Peter. "Sur la critique th6matiqueW, Poktique 16 (1985). 505-16.

Curtius, Ernst 9. Europaische Literatur und Lateinisches Mittelalter. Berne: Francke, 1948, 3rd edn 1961; transl. by Willard Trask as European Literature and the Latin Middle Ages, New York: Rollingen Foundation, 1953.

Curtius, Ernst R. "Antike Rhetorik und Vergleichende Literaturwissen- schaft", Comparative Literature 1 (1949), 24-43.

Czerny, Z. "Contribution a une th6orie compare'e du motif dans les arts", in Stil- und Formprobleme in der Literatur, ed. Paul Rijckmann (Heidelberg : Winter, 1959). pp.38-50.

Daemmrich, Horst S. "Themes and Motifs in Literature: Approaches - Trends - Definition", German Quarterly 58 (19851, 566-75.

Daemmrich, Horst S., and Ingrid Daemmrich. Themes PI Motifs in Western Literature: A Handbook. Tiihingen: Francke, 1987.

Daly, Peter M. Emblem Theory: Recent German Contributions to the Characterisation of the Emblem Genre. Nendeln, Liechtenstein: K T 0 Press, 1979.

Danto, Arthur. The Transfiguration of the Commonplace. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1981.

Dugast, Jacques. "Les gtudes de th&mesW, in La Recherche ... (see under Chardin above), pp. 19-26.

Dyserinck, Hugo. Komparatistik: Eine Einfiihrung. Bonn: BouvierKrund- mann, 1977. Part 11, Ch.1, Section 2 "Die Erfassung des Zusammenhangs der Literaturen in Thematologie und anverwandten Forschungszweigenn, pp.102-13.

Dyserinck, Hugo, and Manfred S. Fisher, eds. lnternationale Bibliographie zu Geschichte und Theorie der Komparatistik. Stuttgart: Hiersemann, 1985.

Falk, Eugene H. Types of Thematic Structure. Chicago and London: Chicago IJP, 1967.

Freedman, William. " The Literary Mot i f : A Definition and Evaluation", 4 (1970-71), 123-31.

Frenzel, Elisaheth. Stoffe der Weltliteratur. Stuttgart: Kroner, 1962, 2nd edn 1963.

Frenzel, Elisabeth. Stoff- Motiv- und Symbolforschung. Stut tgart: Metzler, 1963, 3rd edn 1970.

Frenzel, Elisabeth. "Stoff- und Motivgeschichte", in Reallexikon der ku tschen Literatur~eschichte, 2nd edn, Vol.IV, ed. Klaus Kanzog and Achim Masser (Berlin: de Gruyter, 1965, repr. 19841, pp.213-28.

Frenzel, Elisabeth. Stoff- und Motivgeschichte. Berlin: Schmidt, 1966, 2nd edn 1974.

Frenzel, Elisabeth. Motive der Weltliteratur. Stuttgart: Kroner, 1976.

Giraud, Y. F.-A. "Vers une redkfinition de quelques critsres d'analyse thkmatique: retourner a Wolfflin?", Revue des Langues Vivantes 43 (19771, 492-509.

Glaser, Hermann. Literatur des 20. Jahrhunderts in Motiven. 2 vols, Munich: Beck, 1978-79.

Greverus, Ina-Maria. "Thema, Typus und Motiv: Zur Determination in der Erziihlforschung", in Vergleichende Sa enforschun , ed. Leander Petzoldt (Darmstadt: WB, 1969), pp.-",hia 22 (19651, 131-39.1

Guyard, Marius-Fran~ois. La l i t tkrature compar6e. Paris: PUF, 195 1, repr. 1961. Ch.lV "Genres, ThGmes, Mythes", esp. pp.49-57.

Hall, James. Subjects and Symbols i n Art. New York: Harper & Row, 1974.

Hamon, Philippe. "Theme et effet du &el", ~ o 6 t i q u e 16 (1985), 495-593.

Heinzel, Erwin. Lexikon historischer Ereignisse und Personen in Kunst, L i teratur und Musik. Vienna: Hollinek, 1956.

Heinzel, Erwin. Lexikon der Kulturgeschichte in Literatur, Kunst und %. Vienna: Hollinek, 1962.

Hunger, Herbert. Lexikon der griechischen und romischen Mythologie ... Vienna: Hollinek, 1953, 5th edn 1959.

Herden, Werner. Stoff, Thema, Ideengehalt. Leipzig, 1978.

Jehn, Peter, ed. Toposforschung: Eine Dokumentation. Frankfurt: Athenaum, 1972.

Jeune. Simon. ~ i t t g r a t u r e g6nBrale et l i t tkrature compar6e: Essai d'orientation. Paris: Minard, 1968. Ch.VI "Types et thkmes: vers I'histoire des id6es1', pp.6 1-71.

Jost, Fran5ois. Introduction to Comparative Literature. Indianapolis and New York: Pegasus/Bobbs-Merrill, 1974. Part V "Motifs, Types, Themes", pp. 188-48.

Jost, Fran~ois. "Grundbegriffe der Thematologie", in Theorie und Kri t ik: Zur vergleichenden und neueren Ceutschsn Literatur. FS Gerhard Loose, ed. Stefan Grunwald and Bruce A. Beattie (Berne and Munich: Francke, 1974), pp. 15-46.

Kaiser, Gerhard R. Einfiihrung in die vergleichende Literaturwissenschaft. Darmstadt: WB, 1980. Ch.4, Section 1.3 "Stoffe und Motive . . . I1 , pp.80- 92.

Kalinovska, Sophie-Irene. "A propos d'une th6orie du mot i f l i t t6raire: les formantes", Beitrage zur romanischen Philologie 1 (19611, 78-82.

Kayser, Wolfgang. Das sprachliche Kunstwerk. Berne: Francke, 1948, 6th edn 1960. Ch.11 "Grundbegriffe des Inhalts", pp.55-81.

Klein, Holger M. "Autumn poems: Reflections on Theme as tertium comparationis" (in: Proceedings o f the X l th ICLA Congres, Paris, 1985, ed. Eva Kushner e t al.; forthcoming).

Knapp, Gerhard P. "Stoff - Mot iv - Idee", in Grundziige der Literatur- und Spachwissenschaft, ed. Heinz Ludwig Arnold und Volker Sinemus (Munich: dtv, 19731, pp.200-07.

Knapp, Gerhard P. "Robbespierre: Prolegomena zu einer Stoffgeschichte der franzosischen Revolution", in Elemente der Literatur (see under Baeumer above), pp. 129-54.

Kranz, Gisbert. Das Bildgedicht: Theorie, Lexikon, Ribliographie. 3 vols, Cologne: Biohlau, 1981 (1 and 111, 1987 (111).

Kranz, Gisbert. Das Architekturgedicht. Cologne: Rohlau, 1987.

Krogmann, Willy. "Motiv", in Reallexikon (see under Frenzel above), Vol.11, ed. Werner Kohlschmidt and Wolfgang Mohr, 427-32.

Kruse, Margot. "Literaturgeschichte als Themengeschichte", in Hellmuth Petriconi, Metamorphosen der Traume: Fiinf Beispiele zu einer Literatur- geschichte als Themengeschichte (Frankfurt: Athenaum, 1971), pp.195-208.

Kurman, George. "A Methodology of Thematics: The Literature of the Plague", Comparative Literature Studies 19 (1982), 39-53.

Leach, hlaria, ed. Standard Dictionary o f Folklore, Mythology and Legend. 2 vols, New York: Funk and Wagnall, 1949-50.

Laffont, Robert, and Valentino Silvio Count Bompiani. Dictionnaire des personnages litte'raires et dramatiques de tous les temps et de tous les w. 5 vols. 5th edn Paris: SEDE, 1953.

Les Langues Vivantes 43 (1977), 450-538: Special Section devoted to "Thematiek en thematologie".

Leroux, Claude. "Du topos au theme", P&tique 16 (1985), 445-54.

Levin, Harry. "Thematics and Criticism'' [origin. 1968 in the FS Rend Wellek], in Grounds for Comparison (Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1972), pp.91-109.

Levin, Harry. "Motiv", in Dictionary o f the History o f Ideas, ed. Philip P. Wiener (New York: Scribner, 1973), Vol.111, pp.235-44.

LBtscher, Andreas. Text und Thema: Studien zur thematischen Konstituenz von Texten, Tiibingen: Niemeyer, 1987.

Luthi, Max. Das Volksmarchen als Dichtung. Dusseldorf: Schwann, 1975.

Luthi, Max. "Motiv, Zug, Thema aus der Sicht der Volkserzahlungsforsch- ung", in Elemente der Literatur (see under Baeumer above), Vol.1, pp. 1 1-24.

Lurker, Manfred. Ribliographie zur Symbolkunde. 3 vols, Baden-Baden: Heitz, 1964-66.

Maatje, Frank C. Literatuurwetenschap: Grondlagen van een theorie van het l i teraire werk. Utrecht: Oosthoek, 1970. pp.203-13.

Marcan, Peter. Poetry Themes: A Bibliographical Index ... Hamden, CT: Linnet Books; London: Bingley, 1977.

Modern Language Association of America. Annual International Riblio- graphy.

Miner, Earl, ed. Literary Uses o f Typology from the Late Middle Ages to the Present Day. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1977.

Norstrand, Howard Lee. "Theme Analysis in the Study of Literature", Yearbook of Comparative Criticism 2 (19691, 182-97.

Panofsky, Erwin. Iconography: Humanistic Themes in the Ar t o f the Renaissance. New York: Oxford UP, 1939, repr. Harper, 1962.

Pavel, Thomas. "Le dkploiement de I'intrigue", Poetique 16 (1985), 455-62.

Pichois, Claude, and ~nd r&-M. Rousseau. La l i tt6rature cornparbe. Paris: Colin, 1967. "Th6matologie", pp. 145-54.

Pickett, Ralph E. Recurring Themes i n Art, Literature, Music, Drama and the Dance. New York, 1960.

Poetique 16 (19851, pp.395-516: Special Section devoted to "Thdmatique".

Poggeler, Otto. "Dichtungstheorie und Toposforschung", Jahrbuch fiir Aesthetik und Allgemeine Kunstwissenschaft 5 (1960), 89-201.

Pollmann, Leo. Literaturwissenschaft und Methode. Frankfurt: Fischer Athenlum Taschenbuch, 197 1, 2nd edn 1973. pp. 180-99, 257-69.

Potet, Michel. "Place de la the'matologie", Po6tique 9 (19781, 394-84.

Prawer, Siegbert S. Comparative Literary Studies: An Introduction. London: Duckworth, 1973. Ch.6 "Themes and Prefigurations", pp.99-113.

Prince, Gerald. "Th6matiser", Poe'tique 16 (19851, 425-33.

Ranke, Kurt, et al., eds. Enzyklopldie des Marchens. 12 vols. Berlin: de Gruyter, 1977ff.

Revue de Litte'rature ComparBe. Annual Bibliography.

Rimmon-Kenan, Shlomith. "Que-ce qu'un thbme?", Po6tique 16 (19851, 397-406.

Sauer, Eberhard. "Die Verwendng stoffgeschichtlicher Methoden in der Literaturforschung", Euphorion 29 (19281, 222-29.

Schmitt, Franz Anselm. Stoff- und Motivgeschichte der deutschen Literatur: Eine Bibliographic. Berlin: De Gruyter, 1959, 3rd edn Berlin and New York, 1976.

Schorr, Naomi. "Pour une thkmatique restreinte: kcriture, parole et difference dans Madame Bovary", Litte'rature 22 (1976), 30-46.

Schulze, Joachim. "Geschichte oder Systematik? Zu einem Problem der Themen- und Motivgeschichte". Arcadia 10 (19751, 76-82.

Strelka, Joseph. Methodolo~ie der Literaturwissenschaft. Tiibingen: Niemeyer, 1978. pp. 124-45.

Theile, Wolfgang. "Stoffgeschichte und Poetik: Literarischer Vergleich von Oedipus-Dramen", Arcadia 10 (19751, 34-51.

Thompson, Sti th. Motif-Index of Folk-Literature. 6 vols, Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1932-36, repr. 1955-58.

Tomachevski, Boris. "The'matologie", in Th6orie de la litte'rature, ed. Tzvetan Todorov (Paris: Seuil, 19651, pp.263-307. [Origin. in Russian, 1925.1

Trousson, Raymond. "Plaidoyer pour la Stoffgeschichte", Revue de Litte'ra- ture Comparbe 38 (1964). 101-14.

Trousson, Raymond. Un problkme de littdrature compare'e: Les e'tudes de thhmes. Essai de mbthodologie. Paris: Minard, 1965.

Trousson, Raymond. "Les e'tudes de thgmes: Questions de me'thode", in Elemente de Literatur (see under Baeumer above), pp.1-10.

Trousson, Raymond. Themes et mythes: Questions de me'thode. Brussels: Editions de l '~n ivers i t3 de Bruxelles. 1981.

Van de Waal, Henri, ctd. by L. D. Couprie. Iconciass: An Iconographic Classification System. 2 Parts, Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Co., 1974-80.

Van Tieghem, Paul. La littbrature compar6e. Paris: Colin, 1931. Ch.111 "Th'emes, types et Idgendes", pp.87-99.

Veit, Walter. "Toposforschung: Ein Forschungsbericht", Deutsche Viertel- jahresschrift fur Literaturwissenschaft und Geisteseschichte 37 (19631, 120-63.

Veit, Walter. "'Topics' in Comparative Literature", Jadavpur Journal of Comparative Literature 5 (19661, 39-55.

Vickery, John R., ed. Myth and Literature: Contemporary Theory and Pratice. Lincoln: Nebraska UP, 1966.

Weisstein, Ulrich. Comparative Literature and Literary Theory: Survey and Introduction. Bloomington and London: Indiana UP, 1973. [Origin. in German, 1968.1 Ch.6 "Thematology (Stoffgeschichte)", pp.124-49.

Yearbook of Comparative and General Literature. Annual Bibliography, 1952-69.

Ziolkowski, Theodore. Disenchanted Images: A Literary Iconology. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1977.

Ziolkowski, Theodore. Varieties o f Literary Thematics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1983.

Zumthor, Paul. Langue et tdchniques ~ogt iques dans I'epoque romane. Paris: Klincksieck, 1963.

VENICE AT FIRST SIGHT: PROLEGOMENA FOR A NEW VIEW O N THEMATICS

Angel ika Corbineau-Hoffmann (University o f Mainz)

'I... t h e abundance of a m a t t e r i s o f t e n t o a man a g r e a t e r hindrance than

help".' Th i s observat ion by a man of l e t t e r s2 may b e followed, on t h e

pa r t of any t h e m a t i c s scholar , by a deep, hea r t f e l t sigh. And if th is

scho la r has chose" Venice a s his subject , his image c a n easi ly be t rans-

fo rmed in to t h e c a r i c a t u r e of a man hidden behind his c a r d indexes,

knowing much without unders tanding anything.3 Indeed, themat ics , s ince

t h e ve ry beginnings of compara t ive l i tera ture , has had a bad reputat ion,

encoun te red many c r i t i c s and f ew apologists, and, even worse, t h e most

f amous among t h e fo rmer , but not a lways t h e most reputed among t h e

~ a t t e r . ~ Th i s is, however , not t h e p lace t o t r a c e t h e his tory of themat ics ,

which anyway would b e a sad one ... In modern t imes, during t h e last t w o decades , s o m e a t t e m p t s have

been m a d e t o r ev ive thematics , in pa r t i cu la r by Raymond ~ r o u s s o n ~ and

Manfred ~ e i l e r . ~ T h e discussion cont inues , unanimity among scholars is

not t o b e expec ted , but actual ly a vivid in t e res t in t h e c o n t e n t s of

l i t e ra tu re , neglected for a long t ime, c a n b e d e t e c t e d 7 Th i s is proved

by a special i ssue of Poe'tique, "Du thkme e n litte'rature", in 1985, by a

r ecen t ly published s tudy on topics f rom a linguistic point of view,8 and,

last bu t not leas t , by t h e publication in hand.

Tzve tan Todorov, perhaps speaking not only fo r himself , deplores his

"maigre bagage t h k ~ r i ~ u e " , ~ a l though t h e c o n t e n t s of l i t e ra tu re , t h e

"aboutness" of a text,'' is pa r t of t h e most obvious informat ion it g ives

t o t h e reader . Is t h e problem of t h e m a t i c s only a "chim&re", something

w e b e a r on o u r shoulders wi thout knowing why? I I

A t f i rs t sight, t h e m a t i c s c a n b e summed up and def ined a s t h e

r e fe ren t i a l level of l i tera ture .12 This rough definition, which needs t o b e

m a d e more specif ic , runs g r e a t risk of taking away all possible in t e res t

in s tud ies about themat i c s , s ince t h e evidence does not demand scient i f ic

exploration. T h e "aboutness" of a t e x t s e e m s t o exclude, a f t e r a n initial

look, any o t h e r gl impse a t t h e m a t t e r because of t h e apparen t simplicity

of wha t i s re la ted. If s tud ies in t h e m a t i c s a r e o f t e n isola ted in t h e larger

c o n t e x t of compara t ive l i tera ture ,13 th i s exclusion is perhaps t h e resul t

of the i r own way of t r ea t ing a t ex t , reducing i t t o i t s con ten t or , more

particularly, separating form and content. The following reflections, for

which even a modest word l ike "prolegomena" is not suitable, wi l l t ry to

place a very small aspect o f thematics, namely, the first sight of Venice,

i n i ts poetical context. They want to show that a literary text, in

choosing and treating i ts theme, is merely speaking about i ts own poetics,

and, even more, about the place this theme takes in the realm of human

experience. With some fifteen or twenty pages before us, our subject

must remain only a small section of a larger problem - l ike thematics in

general.

Travelling to I ta ly has, since the late hiliddle Ages, had a long

tradition in the countries of Northern Europe. Considered as a pilgrimage

and, later on, as the grand tour, i t of ten led t o the Venetian Republic, the

capital of which was perceived with astonishment and admiration. The

first sight of Venice, however, inevitable in reality, because the traveller

cannot help looking at the place where he arrives, only hesitatingly finds

i ts way into literature; the reason for this delay is to be sought in the

late discovery of subjectivity in travel literature.14 Indeed, the first

impression Venice makes on i ts visitors implies - besides a personal con-

sciousness - the sensibility for the course of time. The figure o f an

observer struck by the beauty of Venice appears only in the late eight-

eenth century.

Although Francis Mortof t (1658) begins his chapter on Venice by

expressing his astonishment, this reaction can scarcely be called a personal

impression:

Venice I...] which c i t t y is enough to astonish any stranger at f irst sight, to see how the water runs al l about it, being built, as i t were, in the midst o f the sea [...I.

This sentence, summing up a very general f irst vision and the (possible)

astonishment o f any stranger, leads directly t o commentaries on the boats

and "gundaloes", losing sight o f the f irst Venetian impressions.

Another example for an author who preserves his first impressions

in the text he publishes about his travels, is Jean Huguetan in his Voyage

d'ltalie curieux e t nouveau (1681):

Venise nous parut en I'abordant. Cette belle, riche Rr puissante ville, le f~dau des Tyrans, I'azyle des affliggs, & l a Reine de la mer. l6

This way of characterizing Venice by very common and traditional epithets

and metaphors destroys the reader's hope for a personal glance, and the

first sight o f the c i ty conveys less what the author sees than what he

knows: Venice is a commonplace, astonishing, but without any influence

on the traveller's personal view.

These two examples, rare and belated in Venetian travel literature,

serve to show that these accounts, for many centuries, only sum up a

certain knowledge o f the c i t y without finding any personal approach to it.

This impersonality of the f irst impression begins t o change by the middle

o f the eighteenth century: the widespread information about l ta ly in

general, and Venice in particular, calls for innovation, which is given by

travellers l ike Samuel Sharp, Pierre Jean Grosley, Arthur Young and

Hester Lynch Piozzi. A dialogue begins between the town and the visitor.

Through i t s long l i terary tradition, Venice has achieved an obvious inter-

textual density, so that one's f irst perception of the c i ty may evoke other

impressions and recollections, or manifest i t s singularity by comparison and

in contrast to what the visitors know and expect. I n 1720, Edward Wright , speaking of "surprise" l ike many travellers before him, explains this

reaction in evoking a contrast between his expectations and the real scene

before him:

To begin then wi th the distant view o f the Ci ty: 'Tis a pleasure, not without a Mixture o f Surprise, to see so great a c i t y as Venice may be trul ly call'd, as i t were, floating on the Surface o f the Sea; to see Chimneys and Towers, where you would expect nothing but Ship-Masts. 18

The changing language - "pleasure" instead o f "admiration" - announces an

essential difference in perceiving the city. Rut the personal impression

would have been nearly impossible without the previously established

contrast: in the middle o f the sea, indeed, you expect to see ships not

houses and palaces. Venice proves i t s diffkrence at the very moment when

a possible relationship wi th another real i ty comes into sight. Such a

relationship, however, is soon rejected, manifesting the strange peculiarity

o f Venice. I t is by contrast only that this c i t y manifests i t s individuality - i t needs a criterion to measure i t s own value. Young's Travels through

France and l ta ly show the same tendency to value Venice by comparison:

I...] i t was nearly dark when we entered the grand canal. My attraction was alive, a l l expectancy: there was l ight enough to show the objects around me to be among the most interesting I had ever seen, and they

s t ruck m e more than the first en t r ance of any o the r place 1 had been at . 18

It would b e m e r e speculation t o suppose that th is striking impression of

Venice depends on t h e specif ic light when approaching it in the evening

("it was nearly dark"). T h e travel accoun t s before the end of the eight-

eenth century never mention par t icular t imes of t h e day, because they had

not yet discovered any a t t r ac t ion of the atmosphere. The tendency t o

compare Venice with o the r places, t o see it in t h e larger con tex t of what

the t ravel ler had encountered before, t h e discovery of a specif ic a tmos-

phere (of t i m e o r weather) - all t hese innovations a r e t o b e seen in the

con tex t of what may be cal led Venetian relativity: a t t he t i m e I speak

o f , Venice has ceased t o h e incomparable. Si tuated in a g rea te r a r e a of

human experience, t h e c i ty , however, cont inues t o mark i t s individuality,

but only by comparison ("they s t ruck m e more"). Whereas for many

cen tu r i e s Venice had nothing t o b e compared with, t h e t ravel ler now dis-

poses of s o m e prior knowledge, like Pierre-Jean Grosley, who published his

Nouveaux me'moires in 1764:

Ouelque d tude cependant que I'on a i t f a i t e d e ces 6c r i t s 1 sc. su r ~ e n i s e j , on n'est point h I'abri d e la surpr ise qui na?t du premier coup d'oeil: coup d'oeil qui surpasse tou tes les id6es que les rela t ions e t les descriptions peuvent donner ou que I'imagination peut se former. l 9

The "coup d'oeil" of Venice, r epea ted twice, becomes a personal one,

although many writings prepared i t t o such ex ten t tha t it had t o exclude

any so r t of surprise. Venice is not only incomparable, but a lso indescrib-

able: you must have a look a t it. This rescue of Venetian real i ty against

all forms of preparat ive descriptions may b e considered - paradoxically - a s t h e ge rm of Venetian l i tera ture sui generis. T o s e e Venice means t o

feel i t s singularity and difference. Description, a s usual in the traditional

t ravel accounts , i s incompat ible with t h e impression Venice makes on i t s

visitors now. In 1801, Jacques Cambry sums up the l i terary innovations

of his t i m e in writing:

I1 e s t impossible d e ddcr i re I 'effet qu'8 son reveil produit sur le voyageur le premier coup d'oeil su r Venise: c e s canaux bord6s d e b l t i m e n t s d'un goQt si d i f fkrent des fo rmes communes d e I 'archi tecture [...I ici t o u t e analogie e s t interrompue, qui voit Venise voit la ville d'un a u t r e monde. 20

Even i f the singularity is emphasized, this text preserves the idea o f a

correlation: to speak of another world implies a difference to this world - the relationship persists. Strangeness ("&tranget6"), difference, individuality

are only perceptible wi th regard to the normal, everyday experience. This

difference leads to a strange coincidence: Hester Lynch Piozzi, on her

way to Venice, finds the two exactly as i t had been painted by Canaletto - what might seem a fiction of art is confirmed by reality. "It was wonder-

ful ly entertaining", she writes, "to f ind thus realized the pleasures that

excellent painter had given us so many reasons to expect . . .w.~' The

pleasures mentioned are those of art; in her f irst impression of Saint

Mark's Square, Piozzi notices, in particular, a constellation o f ar t i f ic ia l

beauties:

St Mark's Place, af ter a l l I had read and al l I had heard of it, exceedes expectation: such a cluster o f excellence, such a constellation of art i- f icial beauties, my mind had never ventured to excite the idea o f within herself; ... 22

Af ter having heen an admired work of human ingenuity, Venice is now

perceived as a work of art, certainly through Canaletto's influence and

inspiration. Rut whatever the context may be - a l i terary or a pictorial

one - the particular difference o f Venice becomes perceptible only within

a relationship, and by contrast to everyday experience. For many

centuries and for generations o f travellers from the Northern Countries o f

Europe, Venice had been situated within a greater sphere of interest: the

starting point of a voyage t o the Holy Land, later on part o f a journey

through Italy. Certainly, these travellers did not spare their expressions

o f admiration - exceptions confirm the rule - but they were not aware o f

the particular, aesthetic character o f this city. Only by comparison - and

the points o f comparison di f fer from one author to the other - does

Venice prove i ts singularity. When a context o f experience is evoked -

i t may be literary, pictorial or only personal - the special character o f

Venice appears.

I stop for a moment in order to summarise the results and relate

t h e n to the general, theoretical problem o f studies in thematics. If, as

has been said before, the isolation of a thematic approach t o l i terature

seems to ensue from i ts own method, which is to isolate a subject from

i t s context, a glance at Venice illustrates at the same t ime the problem

and i ts possible solution. Venice confirms i ts importance for thematic

studies just at the moment when i t ceases to be an isolated state on the

periphery of Europe, and begins to evoke a larger realm o f human experi-

ence. A t that very moment i t already had a long l i terary tradition, which

is the background for the discovery of i t s individuality. Such a theme may

he considered not only as the content of a text, but also as the result o f

the context of this text. I n a larger sphere o f realistic perception,

aesthetic approach and general human experience, the more or less

accidental content of literature becomes a theme - in the most complex

sense o f the term.23 The tilore the Venetian context grows, the more

literature transforms the first glimpse of Venice into a significant,

striking experience, enriched with personal imagination and linguistic or

l i terary connotations: the "f irst sight" tends to lose i ts only visual

qualities in order to become a metaphor for an insight - and this inner

dimension comprehends, in an intimate dialogue, both the c i ty and the

author.

In describing what he sees and not what he knows - about Venice and

i ts strange situation in the sea - Charles Dickens transforms his nocturnal

arrival in Venice into an "Italian ream".^^ Through such an impressionist

procedure (ante l i t teram) Venice loses al l i t s realistic elements, transform-

ing itself into a dreamy picture the meaning of which has to be decoded

by the reader. For Dickens, Venice is a nameless place, although every

reader recognizes it. The reason for this transformation is twofold: when

approaching the city, the boat passes a cemetery, and the following des-

cription confers upon the c i ty itself the character o f a burial place. As

sleep has been considered as the brother of death since antiquity, the

author's state o f mind becomes strangely similar to the state of the

dying city. Being only a vision and not a realistic image, Venice is

separated from al l information with which former periods had burdened it.

Dickens' "first sight", although meaning, within the framework of the

narrative, the f irst view he gains o f Venice, is essentially a primary one,

as i f the author did not know anything about the city, seeing i t for the

f irst time. In a sort o f mythical construction, this first glimpse is, at the

same time, the absolute beginning and definit ive end, holding reality in

suspense, neutralizing the common differences between past and present,

between l i fe and death, between f ict ion and reality. Even the question

of whether the traveller is asleep or awake is le f t unanswered: in his

dreams, the author wakes up or falls asleep, destroying all possible

specu la t ion about t h e s t a t u s of r ea l i t y in his text . T h e cons t i t u t ion of

sense , d i f f e ren t t o all w e a r e f ami l i a r wi th in t h e l i t e r a t u r e abou t Venice,

is e f f e c t e d beyond realism. In th i s "ghostly c i ty" wi th i t s "phantom

street^",^' visual impress ions a r e n o longer a dup l i ca t e o f t h e c i ty ' s own

s t ruc tu re , but a n agglomerat ion of d e t a i l s wi thout any obvious s ignif icance -

a w a y of suspending all k inds o f meaning o n c e and fo r all. T h e following

passage conf i rms th i s i n t e rp re t a t ion :

O t h e r boats , o f t h e s a m e sombre hue, w e r e lying moored, I thought , t o pa in t ed pillars, n e a r t h e da rk mys te r ious door s t h a t opened s t r a igh t upon t h e water . S o m e of t h e s e w e r e empty ; in some , t h e rowers lay as leep; t owards one, I s a w s o m e f igures coming down a gloomy a rchway f rom t h e in t e r io r o f a palace; gai ly dressed, a n d a t t e n d e d by torch-bearers . 26

Jus t l ike t h e t e x t in general , t h e s ignif icance of t h e s e s e n t e n c e s r ema ins

in a s o r t of darkness. F o r Dickens, t h e r e i s no reason t o desc r ibe Venice

y e t again , a f t e r all t h e t r ave l a c c o u n t s which had m a d e it a sub jec t of

c o m m o n knowledge. T h e ve ry ob jec t of t h i s t e x t is n o longer a c i t y

ca l l ed Venice, but a quest ion ra ised by a t r ad i t i on of l i t e r a tu re beginning

wi th t h e Venet ian f ic t ion by M m e d e S t a e l a n d Lord Byron, namely, t h e

s t a t u s o f reality. By cons t ruc t ing a world m a d e of words, Dickens p l aces

Venice beyond th i s world, in t h e r ea lm of d e a t h and f ic t ion, pe rcep t ib l e

only in a d ream. T h e dissubstant ia t ion could hardly b e g rea t e r . But t h i s

t r anscendance o f Venice s u m s u p f o r m e r a t t e m p t s t o c r e a t e a f ic t ic ious

c i t y , symbol of pol i t ica l d e a t h a n d l i t e r a ry resurrect ion. Dickens' c i t y

wi thout a n a m e is, never theless , impregna ted wi th a meaning which

conce rns not only t h e individual t r ave l l e r , bu t humani ty in general : beyond

o u r world of expe r i ence , w e find a n o t h e r real i ty , a r ea lm of d r e a m and

f ic t ion, a my th ica l p l ace of refuge.

S ince t h e e n d of t h e e igh teen th cen tu ry , t h e c o n t e x t of Venet ian

t r ave l has changed. Ce r t a in ly , i t w a s l i t e r a ry f o r H e s t e r Piozzi just a s

i t w a s fo r Dickens, bu t t h i s l i t e r a t u r e i t se l f w a s sub jec t t o t ransformat ion.

S ince f i c t i t i ous persons l i ke Cor inne o r Chi lde Harold had submi t t ed Venice

t o t he i r own visions, t h e c i t y had a s sumed a l a rge r spec t rum of meaning

t h a n e v e r before . I t s r e a l a spec t , including palaces , paint ings a n d churches ,

had b e c o m e a c ryp tog raphy fo r a d e e p e r sense: t h e d e a t h of beau ty on

e a r t h a n d i t s r e su r r ec t ion in t h e ar ts . T h e dest iny of Venice i s n o longer

a pol i t ica l quest ion, b u t a n a e s t h e t i c and par t icular ly a poet ical one. S o

Dickens ' phantom c i t y does no t only r e f e r t o a f i rs t g l impse of nocturnal

Venice in a dream (all this may be considered as a poetical, f ict i t ious

construction), but also to a l i terary artefact which, during the first

decades of the nineteenth century, had lost much o f i ts referential reality.

Gaining a new sense as a c i ty of death, Venice now implies the experience

of transcendence, and i ts geographical and polit ical situation, as well as

i ts exterior beauty, refer to a place somewhere beyond this world. The

c i ty has a new existence in literature, which cannot be destroyed by the

changing of t ime and the vicissitudes o f fortune. Even i f i t is a dead, a

burial place, in this quality i t survives - paradoxically. The death of

reality guarantees the survival of fiction. Dickens' "Italian Dream", an

impressionistic sketch rather than a realistic description, creates and marks

a new relationship between Venice and literature. The first sight discovers

a c i ty o f death in a metaphorical sense: reality did die, but literature,

even in representing this death, discovers a new sense in the concept of

Venice: geographically marginal in Europe, Venice now becomes the

threshold of another world - at f irst sight.

Although highly unrealistic, Dickens' impressions are not singular and

extravagant. Only a few years later, in 1852, Gautier describes his arrival

in Venice in a comparable way. Night and darkness suspend the ordinary

relationships between objects. Some lights appearing here and there

accidentally lay stress on picturesque scenes:

L'orage qui t i ra i t B sa fin, illuminait encore le ciel de quelques l u e ~ ~ r s livides qui nous trahissaient des perspectives profondes, des dentelures bizarres de palais inconnus. A chaque instant I'on passait sous des ponts dont les deux bouts rdpondaient B une coupure lumineuse dans la masse cornpacte et sombre des maisons. A quelque angle une veilleuse tremblait devant une madone. Des cris singuliers et gutturaux retentissaient au detour des canaux; un cercueil flottant, au bout duquel se penchait une ombre, f i la i t rapidement b c6td de nous; une fendtre basse raske de pr&s nous faisait entrevoir un inte'rieur e'toile' d'une lampe ou d'un reflet, comme une eau-forte de Rembrandt. 27

What was implicit in Dickens' prose, the reference to l i terature and art,

becomes explicit in Gautier's text: the l ight effects make appear "des

figures e m b ~ k m a t i ~ u e s " , ~ ~ cut o f f from their ordinary surroundings. A

world which loses i ts normal relationship receives a strange new structure,

analogous to the isolating process o f art. Gautier's f irst perception of

Venice may be compared to the different ways o f looking at a collection

o f paintings and drawings, and his arrival in Venice resembles a visit to

a gallery. But more than a transposition of well-known artistic impres-

sions into a poetical reality, Venice in Gautier's description becomes a

place of exuberant imagination and mysterious threat. In the passage

quoted above, "bizarre", "singulier", "cercueil flottant", though not the

most significant in this respect, indicate a menace inherent in Venice.

Gautier speaking of "l'hippogriffe d'un cauchemar" and of "un voyage dans

le noir, aussi itrange, aussi mysterieux que ceux qu'on fait pendant les

nuits de c a ~ c h e m a r " , ~ ~ adds a connotation of danger to Dickens' nocturnal

impressions: the dream is now a nightmare. Thus, it appears less as a

state of suspense between fiction and reality than as a realm of imagina-

tion - Venice city of the soul and of its spectres. If it has been empha-

sized before that Dickens' reference was a tradition of fictitious literature,

now this implicit context becomes explicit in Gautier's description:

Nous croyions circuler dans un roman de Maturin de Lewis ou d'Anne Radcliff illustrk par Goya, Piranbe et Rernbrandt. 30

Gautier is right in thinking of the gothic novel, because preromantic and

romantic Venetian fiction often follows this t r a d i t i ~ n . ~ ' His somewhat

excited imagination reaches historical truth. What seems to be exaggera-

ted "est de la r6alitk la plus exacte":

Une terreur froide, humide et noire comme tout ce qui nous entourait, s'ktait emparke de nous, e t nous songions involontairement B la tirade de Malipiero h la Tisbe', quand i l depeint I'effroi que lui inspire ~enise.32

Indeed, Hugo's Angelo, which Gautier refers to, is one of the most striking

examples of Venetian "darkness".33 Transformed into a literary place, a

scene of dramas and novels, Venice presents to the visitor an imaginary

stage decoration:

Cette impression qui semblera peut-btre exage're'e, est de la verite' la plus exacte, e t nous pensons qu'il serait difficile de s'en de'fendre, m6me en philistin le plus positif; nous allons mdme plus loin, c'est le vrai de Venise qui se d6gage. la nuit, des transformations modernes; Venise, cette ville, qu'on dirait planthe par un d6corateur de thkltre, et dont un auteur de drame semble avoir arrange les moeurs pour le plus grand intkrdt des intrigues et des de'n0uements.3~

Venice a theatre of dreams - reality, Gautier tells us, resembles itself:

but what reality? A tourist's first impression turns out to be the effect

of literary knowledge, and Venice, the place of action, is changed into a

stage. The difference between fact and fiction, between geographical

places and imaginary stages, is abolished, and what Gautier calls "reality"

is to be understood as an inextricable mixture of impressions and inven-

tions. Nevertheless, i t is necessary to emphasize a mere fact which, as

i t stands, has nothing to do with any real or fictitious travel to Venice.

Since the end of the Serenissima Repubblica, Venice, the victim of foreign

political interests, has gained in literature what i t lost in politics. Its

insignificance in real (economic, political) l i fe is compensated by new

literary and aesthetic values. The purely imaginary constructions of

literature make Venice the centre of a new interest, and even more,

confer a new reality on the city of fiction. This complex correlation

makes the real sense of Gautier's strange arrival at the city a pragmatic

fact which leads to an encounter with literary reality or real fiction.

I f theatre can be defined as that which is shown - and Gautier

pretends that he has before his eyes all he describes - a fairy tale, as the

term indicates, is something which must be @Id. The marginal situation

of Venice in Europe, which links up with a general tendency of poetical

evasion in the nineteenth century,35 encounters during these 1850s another

paradigm, more literary and even more fantastic. In a forgotten German

text, Pecht's Ein Winter in Venedig, Venice appears as a fairy tale made

of stone:

So ware ich endlich in diesem Stein gewordenen Mlrchen, dieser zauber- haften Stadt angelangt, die mit keiner anderen verglichen werden kann und von keiner anderen an Reiz ubertroffen. Strenge deine Phantasie an, wie du willst, zum Wunderbarsten und Abenteuerlichsten, Venedig wird es iiberbieten. 36

The author's allusion to a fairy tale means more particularly the collection

of A Thousand and One Nights, where Sheherazade tells her stories in

order to remove the menace of death. The analogy to the fate of Venice

and to the function of Venetian literature is quite obvious. In Pecht's

text, Venice is transformed into a scenery of oriental fantasy - a stage

which, for the duration of the fictitious representation, stops the course

of time. This realm of connotations, underlining not only the peculiar

quality of the city, but also i ts mythical power to escape from political

death, refers to the concept of imagination. Definitively, the referential

level of Pecht's text is less the real appearance of Venice than the

author's and the reader's consciousness, or, in Husserl's terms, his "experi-

ence": 37