02 realism edouard manet

-

Upload

melanie-powell -

Category

Education

-

view

103 -

download

0

Transcript of 02 realism edouard manet

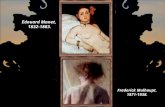

Édouard Manet French b.1832 – d.1883

circa 1867-1870

Before looking at the origins of this painting, try to unravel its formal qualities. (Read and understand this part).

The materials, techniques and processes used in a painting help to determine the work’s appearance and have an effect on the way we understand and interpret the work.

What materials have been used?How have the inherent characteristics of the materials been used by the artists (e.g. watercolour’s transparency, the quick drying property of tempera that does not allow colour to be blended easily, other than by hatching, oil paint’s versatility to create translucent layers (glazes) to thick impasto)? What is the painting’s support (the surface on which the paint is applied)?

Is there evidence of what tools the painter has used?

Have the medium, support and/or tools used helped to determine the paintings scale?

Take the Formal Features of painting listed here and consider them to begin a discussion of Manet’’s painting, Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe

Formal Features1. Composition 2. Colour3. Pictorial space4. Light and tone5. Form6. Line7. Scale 8. Pattern/Ornament/Decoration

Write the list down and use it as a reference when discussing formal qualities of paintings in the future

Édouard Manet, Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe (The Luncheon on the Grass)1863, Oil on canvas , 208 cm × 264.5 cm. Musee d’Orsay

Here is the title and details of Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe

Refer to the Formal Features list and discuss/annotate this painting .Use the next slide.

The Judgment of Paris, ca. 1510–20. Marcantonio Raimondi (Italian, ca. 1480–before 1534). Designed by Raphael (1483–1520) Italian. Engraving 29.2 x 43.6 cm

The Judgment of Paris, ca. 1510–20. Marcantonio Raimondi (Italian, ca. 1480–before 1534). Designed by Raphael (1483–1520) Italian. Engraving 29.2 x 43.6 cm

The background of this version of ‘The Judgment of Paris’A masterpiece of Renaissance printmaking, this work represents a high point in the collaboration between Raphael and Marcantonio. While Marcantonio sometimes worked from drawings created for other projects, in this case Raphael created the drawing for the sole purpose of having it engraved by Marcantonio. Drawings done, as Vasari tells us, "to please himself," gave Raphael a forum in which to explore the ancient motifs that so fascinated him, while the process of printing ensured that Raphael's private research would be known to a wide audience. The engraver's controlled, systematic line, curving around the figures, gives them a great three-dimensional presence.At the wedding of King Peleus of Thessaly and the sea goddess Thetis, Strife showed up uninvited and threw into the midst of the guests a golden apple inscribed "to the fairest." To put an end to the squabbling between Minerva (Athena), Venus (Aphrodite), and his wife Juno (the Greek Hera), Jupiter decreed that the handsomest man on earth, a Trojan prince raised as a shepherd, would be the judge. All of the goddesses bribed Paris, but Venus—promising him the most beautiful woman in the world as his bride—won the contest. Unfortunately, her candidate was already married, and Paris' abduction of Helen from her Greek husband sparked the Trojan War.In illustrating this ancient myth, Raphael drew inspiration from the relief sculpture found on two ancient Roman sarcophagi (stone burial caskets). Marcantonio's controlled and systematic line, curving around the figures, beautifully conveys the sculptural quality that Raphael sought. The rich areas of gray tone were created through an unusual procedure: before engraving the lines, Marcantonio roughened the metal plate with pumice, so that all areas not later burnished smooth hold some of the ink in their textured surface.

Detail of The Judgment of Paris, ca. 1510–20. Marcantonio Raimondi (Italian, ca. 1480–before 1534). Designed by Raphael (1483–1520) Italian. Engraving 29.2 x 43.6 cm

This painting has been cited as an inspiration for Manet's The Luncheon on the Grass.

By Giorgione or Titian, The Pastoral Concerto, 1510, Oil on canvas105 × 137cmLouvre, Paris

Manet allows the pale flesh of the naked woman to glare flatly as if spot-lit, while the dark coats of the men are flat and black. The paint handled with abrupt sketchiness. The woman with her wet chemise in the river is, in conventional term, no more than a rough sketch, and the landscape is sketched with improvised speed. In short, the painting appears unfinished. But this is part of it being ‘of the moment’, fresh and direct.

The Luncheon on the Grass, 1862 by Edouard Manet Luncheon on the Grass

Luncheon on the Grass ("Dejeuner sur l'Herbe," 1863) was one of a number of impressionist works that broke away from the classical view that art should obey established conventions and seek to achieve timelessness. The painting was rejected by the salon that displayed painting approved by the official French academy. The rejection was occasioned not so much by the female nudes in Manet's painting, a classical subject, as by their presence in a modern setting, accompanied by clothed, bourgeois men. The incongruity suggested that the women were not goddesses but models, or possibly prostitutes.

Yet in Le dejeuner sur l'herbe, Manet was paying tribute to Europe's artistic heritage, borrowing his subject from The Pastoral Concert - a painting by Titian attributed at the time to Giorgione (Louvre) - and taking his inspiration for the composition of the central group from the Marcantonio Raimondi engraving after Raphael's Judgement of Paris.But the classical references were counterbalanced by Manet's boldness. The presence of a nude woman among clothed men is justified neither by mythological nor allegorical precedents. This, and the contemporary dress, rendered the strange and almost unreal scene obscene in the eyes of the public of the day. Manet himself jokingly nicknamed his painting "la partie carree".

Manet displayed the painting instead at the Salon des Refuses, an alternative salon established by those who had been refused entry to the official one. Like his friend Courbet, Manet influenced modern painting not only by his use of realistic subject matter but also by his challenge to the three-dimensional perspectivalism established in Renaissance painting. Manet painted figures with a flatness derived partly from Japanese art and resembling (as Gustave Courbet commented) the flatness of the king or queen on a playing card.

Luncheon on the Grass - testimony to Manet's refusal to conform to convention and his initiation of a new freedom from traditional subjects and modes of representation - can perhaps be considered as the departure point for Modern Art. The modernist reinvention of pictorial space had begun.

Edouard Manet, Olympia. 1863 Oil on canvas. 130.5 × 190 cm. Musée d'Orsay. Olympia_Khan Academy

Venus on seashell, from the Casa di Venus, Pompeii, Before 79 AD.Aphrodite of

Melos(Venus de

Milo)marble 2.04

m. Louvre Paris, France

Sandro BotticelliThe Birth of Venus 1482 and 1485Oil on canvasUffizi, Florence

Titian ,Venus of Urbino 1583 Oil on canvas. Uffizi ,Florence

1 2

Giorgione (Giorgio Barbarelli da Castelfranco)Sleeping Venus.C. 1510Oil on canvas

Titian, Venus of Urbino 1583

Edouard Manet, Olympia. 1863

Francisco de Goya La Maja Desnuda(The Naked Maja),Before 1800Oil on canvas98 x 191 cm. Museo Nacional Del Prado

Francisco de GoyaLa Maja Vestida(The Clothed Maja), Between 1798–1805oil on canvas97 cm x 1.9 m. Museo Nacional Del Prado

Goya’s La Maja Vestida and La Maja Desnuda, installed at the Prado

Edouard Manet, Olympia. 1863 Oil on canvas. 130.5 × 190 cm. Musée d'Orsay. Olympia_Khan Academy

Manet’s Olympia caused a scandel when it was exhibited at the 1865 Salon in Paris. Visitors to Salon were used to nudity in painting – but they were used to seeing it in a Classical context.A nude was Venus, or a nymph, and usually alluded to a well-known myth or a passage of Classical history. In Olympia they saw a ‘real’ nude presented without reference to the Classical world, a prostitute who evoked the Parisian street rather than the Classical past.

With Olympia, Manet reworked the traditional theme of the female nude, using a strong, uncompromising technique. Both the subject matter and its depiction explain the scandal caused by this painting at the 1865 Salon. Even though Manet quoted numerous formal and iconographic references, such as Titian's Venus of Urbino, Goya's Maja desnuda, and the theme of the odalisque with her black slave, already handled by Ingres among others, the picture portrays the cold and prosaic reality of a truly contemporary subject. Venus has become a prostitute, challenging the viewer with her calculating look. This profanation of the idealized nude, the very foundation of academic tradition, provoked a violent reaction. Critics attacked the "yellow-bellied odalisque" whose modernity was nevertheless defended by a small group of Manet's contemporaries with Zola at their head.

Edouard Manet's Olympia 1865 PBS Culture ShockWhen Edouard Manet's painting Olympia is hung in the Salon of Paris in 1865, it is met with jeers, laughter, criticism, and disdain. It is attacked by the public, the critics, the newspapers. Guards have to be stationed next to it to protect it, until it is moved to a spot high above a doorway, out of reach. With Olympia, Manet rebels against the art establishment of the time. Taking Titian's Venus of Urbino as his model, Manet creates a work he thinks will grant him a place in the pantheon of great artists. But instead of following the accepted practice in French art, which dictates that paintings of the figure are to be modelled on historical, mythical, or biblical themes, Manet chooses to paint a woman of his time -- not a feminine ideal, but a real woman, and a courtesan at that. And he paints her in his own manner: in place of the smooth shading of the great masters, his forms are painted quickly, in rough brushstrokes clearly visible on the surface of the canvas. Instead of the carefully constructed perspective that leads the eye deep into the space of the painting, Manet offers a picture frame flattened into two planes. The foreground is the glowing white body of Olympia on the bed; the background is darkness. In painting reality as he sees it, Manet challenges the accepted function of art in France, which is to glorify history and the French state, and creates what some consider the first modern painting. His model, Victorine Meurent, is depicted as a courtesan, a woman whose body is a commodity. While middle-and- upper class gentlemen of the time may frequent courtesans and prostitutes, they do not want to be confronted with one in a painting gallery. A real woman, flaws and all, with an independent spirit, stares out from the canvas, confronting the viewer, something French society in 1865 is perhaps not ready to face. After Manet's death, the painter Claude Monet organizes a fund to purchase Olympia and offers it to the French state. It now hangs in the Musée D'Orsay in Paris, where it is considered a priceless masterpiece of 19th French painting.

Edouard Manet, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère1882, oil on canvas, 96 cm × 130 cm. Courtauld Gallery, London

This paintingWas Manet’s last major work.

In the Making

Far from being quickly and spontaneously painted, the composition was the result of careful preparatory studies. However, that is not to say that Manet did not make changes as he painted. In an x-ray of the final canvas, we can see that Manet initially painted the barmaid with her arms crossed across her waist, her right hand clasping her left arm above the wrist. This gesture emphasised her glovelessness, but is also one of protection. The woman in the background looking through opera glasses was a late addition.